1. Introduction

It is now a widely accepted fact that urgent action is needed to tackle climate change and global social inequality (e.g., UN Sustainable Development Goals 2020). Various studies discuss whether and which models of sustainable or ecological citizenship can serve as feasible means to meet this challenge. These models usually look at two sides. The first side considers performances like sustainable consumption, while the second includes attitudes, resources and rules that enable and motivate citizens to act sustainably.

This article approaches the question of ecological (

Dobson 2003) or sustainable (

Micheletti and Stolle 2012) citizenship from a new perspective, claiming that much of the literature focuses too much on the theoretical and deductive modeling of the two sides. Rather than proposing another ideal of sustainable citizenship (see also

Bell 2005;

Dean 2001;

Barry 1999), we attempt to identify how its real-world shape is delineated in practice, and to learn from this what sustainable citizenship is and on what it is grounded.

Various authors have called in this regard for grounding sustainable citizenship empirically by following the practice turn (

Shove 2010;

Evans 2019). From a practice-theoretical point of view, sustainable citizenship consists of one or more social practices in the sense of “temporally unfolding and spatially dispersed nexus of doings and sayings” (

Schatzki 2008, p. 89). In contrast to modeled concepts of action forms, thus a practice is an empirically realized, relatively stable pattern of performing in a customary manner. While the term ‘action’ usually sheds light on idiosyncratic acts, the concept of a ‘practice’ focuses on the regularities within human conduct. Practice theory furthermore assumes that citizens learn a practice by repeatedly doing it while following the example of fellow citizens, so that the related practice becomes a habit. A practice then relies on “tacit knowledge” (

Collins 2001) or on ‘know how’, which most of the time ‘goes without saying’. Practice theory does not claim that people act merely like trained animals. Nonetheless, it opposes an excessive “mentalism” (

Reckwitz 2002, p. 258) which views cognitive reflection to precede each single act of doing or saying. Instead, humans are conceptualized as actors that through ‘learning by doing’ have obtained the competencies of how to do, say, feel and think within a certain practice in precisely that sequence. Practice theory thus sets competencies of bodily performances within a social and material environment before individual cognitive reflection. Sustainable citizenship from this perspective then needs to be conceptualized as consisting of competencies and routine behaviors that belong to the customs and habits of a given political culture. While, we refer to this understanding of the practice turn, this article differs from the mainly qualitative studies in this direction (e.g.,

Evans 2019) in two regards.

First, while most of the qualitative research focuses on reconstructing corporeal performances, their obstacles and opportunities, the main motive we adopt from the practice turn is its Wittgensteinian urge to reconstruct rather than to model the inherent regularity and the shape of practices which, at the same time, become the basic units of analysis (

Schatzki 2008). Thus, rather than defining sustainable citizenship ex ante, scholars should reconstruct sustainable citizenship based on what people do when they perform in everyday life. The idea is to readdress the conception of the units of analysis, reconstructing them according to the boundaries that empirical patterns of doings and sayings draw. Therein, concepts of sustainable citizenship can still be used. Yet, instead of using a single definition of sustainable citizenship, we suggest operating with a broad set of possible performed practices and underlying dispositions, of which some might turn out during analysis as a dominant pattern of sustainable citizenship practiced empirically.

Second, existing studies on sustainable citizenship following the practice turn usually lack the ability to overcome the limited empirical scope of qualitative field research (e.g.,

Kennedy and Bateman 2015;

Sahakian and Wilhite 2014). We apply a quantitative methodology that allows for reconstructing sustainable citizenship inspired by the practice turn. While we acknowledge that there is a deep philosophical and methodological abyss between statistical research and the practice turn, we argue that statistics offers a kindred methodology, namely principal component analysis (PCA). This methodology allows for clustering activities and attitudes as indicators for practices and dispositions according to concurrent survey responses. Thus, the empirical concurrence of activities and attitudes, not the scholar model, may indicate practices and dispositions according to the boundaries identified by the help of PCA. From that perspective, this explorative method resembles the hermeneutical methods that most proponents of the practice turn use.

By following the practice turn, we can broaden the range of hypothetical constellations of dispositions and practices (e.g.,

Jagers et al. 2014;

Martinsson and Lundqvist 2010). Specifically, we can bring together items and insights from quantitative studies about political consumerism (e.g.,

Stolle and Micheletti 2013) and sustainable consumption (e.g.,

Azzurra et al. 2019). Surprisingly, the related literatures on sustainable citizenship, sustainable consumption and political consumerism have yet taken little notice of each other, although they share a common focus on sustainable behavior. The reason might be that political consumerism is usually narrowed down to politically motivated purchasing (buycotting) and boycotting. The literature on sustainable citizenship and consumption, in turn, usually includes a wider range of seemingly apolitical lifestyle practices, such as sorting waste. At the same time, quantitative studies on political consumerism investigate a wider set of dispositional factors than comparable qualitative works on sustainable citizenship do, including norms of citizenship, values, trust, purchasing criteria and socio-economic status data. Bringing together these literatures thus provides for a larger set of possibly relevant aspects for our empirical investigation of the real-world shape of sustainable citizenship.

Therefore, following the practice turn’s call for deriving the shape of a unit of analysis from empirics first, we will make use of existing literatures in order to maximize the range of empirically possible patterns of performances and dispositions of sustainable citizenship. Guided by the research question of what constitutes and delineates sustainable citizenship in practice, the aim is to identify what forms of real-world practices of sustainable citizenship exist, and which dispositions accompany them. Using survey data from Germany for the year 2014 (N = 1350), we show how in this way, the sides of dispositions and performances both expand, so that they come to include aspects such as critical political attitudes whose missing was bemoaned by critics of sustainable citizenship.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Ecological Citizenship and Sustainable Consumption

There are many accounts of ecological, environmental or sustainable citizenship, yet Andrew Dobson’s concept of “ecological citizenship” (

Dobson 2003, pp. 83–140) is generally referred to as a common point of reference (e.g.,

Seyfang 2005;

Scerri 2009). In view of severe environmental degradation, Dobson’s aim is to formulate a prescriptive ideal. Climate change should be tackled by each citizen depending on her or his respective ecological footprint. This implies that most citizens in wealthier countries need to downsize their consumption, whereas less affluent citizens could yet expand their consumption. With this central role of social fairness, the model can be subsumed under the larger umbrella of understandings of sustainable citizenship (e.g.,

Micheletti and Stolle 2012).

Furthermore, Dobson argues that citizens are obliged to take action in their private realms and irrespective of their national backgrounds, because ecological problems are of transborder nature and caused, to a large extent, by private consumption. As a result, he presents ecological citizenship as a two-sided ideal. Deep change needs to occur on the side of dispositions so that citizens develop the virtue to acknowledge their responsibilities and feel obliged to change their private lives. On the side of performances, educational measures shall help to spread pro-environmental behavior and sustainable consumption (

Dobson and Bell 2006).

Citizenship can be studied as referring to a legal status of persons, as a form of collective identity, or as a system of duties and rights (

Tonkiss and Bloom 2015, p. 838). Dobson’s approach clearly belongs to the latter approaches. However, Dobson does not hide the fact that his concept of ecological citizenship transcends rather than continues within the long-standing understanding of the concept of citizenship of political science and history. His main intention is to propose a feasible way ‘to save the planet’ in ecological terms. Against this backdrop, he explicitly rejects the focus of citizenship studies from after the Second World War on the expansion of rights and entitlements. In particular, he criticizes T. H.

Marshall’s (

1950) influential approach as unhelpful in the ecological question, since he views it as to neglect the urgently needed activation of citizens. Marshall stressed that citizenship rights in Britain have expanded from civil rights in court to political rights at the ballots and, eventually, towards social rights within the welfare state. In contrast,

Dobson (

2003, pp. 40–44) urges to revive an understanding of citizenship that stresses obligations and responsibilities of citizens to contribute to public welfare. Nonetheless, to date, the major part of research on citizenship stresses the empirical relevance of Marshall’s works (e.g.,

Evers and Guillemard 2013).

In another seminal account, Brian S. Turner’s two-dimensional space of citizenship meets Dobson’s skepticism (

Dobson 2003, pp. 36–37).

Turner (

1997) argues that the understanding of citizenship in different countries can be depicted along two dimensions. On the vertical axis, citizenship was historically either entitled from above, like in Britain or Germany; or it was appropriated from below, as, for example, in the U.S. and in France. On the horizontal axis, the purpose of the concept of citizenship varies from producing public goods (France and Britain) opposed to secure (U.S.) or control (Germany) the private conduct of life. Dobson is not engaging with Turner’s proposal in detail, but criticizes that it is normatively centered on rights. Likewise, in his urge for citizens’ obligations, he shows no further interest in Turner’s two-dimensional space. However, it could have helped him to see that his and other formulations of ecological citizenship are “unnecessarily and unfortunately narrow” and show “elitist leanings” (

Gabrielson 2008, p. 441), since they unintentionally end up in proposing—at least from the viewpoint of Turner’s approach—to revive a rather top-down and passive citizenship model. Nonetheless, Dobson’s approach, at the same time, was path breaking, since he abandons an understanding of citizenship bound to counterfactual contracts within the nation-state and understands ecological citizenship instead as a practice to spread across the globe.

Various qualitative case studies have applied this ideal empirically (

Kenis 2016;

Islar and Busch 2016). Our interest lies in the methodology and results of their attempts to survey ecological citizenship.

Martinsson and Lundqvist (

2010) evaluate Dobson’s ideal using survey data from Sweden. They measure the attitudinal side through five items relating to the salience people attribute to environmental issues, related interests, values and concerns. The side of performances is measured through an additive index consisting of 13 equally weighted items referring to green mobility, energy use, purchases (buycott) and sorting waste. In sum, they apply ecological citizenship as an ideal, deduced from a theoretical model which they verify. However, this approach neglects which and how many forms of citizenship the surveyed citizens actually practice. Kjeld

Schmidt (

2015), in this regard, coined one of the most important maxims of the practice turn with the words that “(p)ractice must speak for itself” which means, empirical patterns must be observed ahead of their theoretical modelling.

This does not mean to neglect the importance of theoretical reasoning. In fact, another study from Sweden suggests that Dobson’s idea resonates with reality.

Jagers et al. (

2014) undertake the attempt to measure the complex theoretical argumentation of Dobson. With twenty items, they measure four theoretical dimensions on the attitudinal side. These dimensions are (1) the belief in fairness expressed as a sense that citizens should save the planet for future generations; (2) the willingness to take over responsibility within private realms; (3) the recognition of transborder obligations; and (4) the consent that citizens with larger ecological footprints need to downsize their consumption more than citizens with small footprints. On the side of performances, they use twelve items which compare to those applied by

Martinsson and Lundqvist (

2010), including different forms of boy- and buycotting, plus activities like purchasing second-hand and avoiding meat consumption.

The two sides—attitudes and performances—are then condensed into additive indexes. Using multivariate regression analysis, the authors find that the combination of all four attitudinal dimensions explains adoption of pro-environmental behavior better than simple measures of ecological values. Nevertheless, only two dimensions—fairness and private responsibility taking—prove robust predictors of pro-environmental behavior. With this, the two studies seem to prove the real-world relevance of the sustainable citizenship ideal in Sweden. But they also suggest that people in general do not respond to Dobson’s full theoretical argumentation. Instead, the ‘sustainable citizens’ appear to be mainly concerned about intergenerational fairness and individual responsibility.

Finally, a growing number of quantitative studies analyze the same empirical phenomena with the help of different concepts.

Azzurra et al. (

2019), for example, measure ‘sustainable food consumption’ (buying organic food for ecological and social reasons) in relation to ‘sustainable lifestyles’ (recycling, sorting and reducing waste, green mobility, voluntary work) and ‘sustainable purchasing criteria’ (ecological and social concerns). Based on the three respective measures that they develop, they identify a strong relation between the three practices. Similarly,

Fischer et al. (

2017, p. 322) develop two measurement scales based on items covering the whole process of consumption across the phases of acquisition, usage and disposal in order to study sustainable consumption as consisting of eating, clothing and related purchasing criteria.

These and other studies illustrate that there might be alternative ways to define and measure sustainable citizenship. The side of performances focuses on purchases and measures them more systematically, while the side of dispositions considers foremost practically guiding purchasing criteria, and less-so socio-ecological values. Studies on sustainable consumption thus may help us to enhance the set of possible elements of sustainable citizenship in the real world and add to works that apply Dobson’s citizenship ideal.

Further sources for a broadened conceptual horizon can be found within critiques of Dobson’s formula of sustainable citizenship, since these critiques point at some empirical blind spots. Critics mainly advance two points. First, it is bemoaned that the responsibility of the state as a provider of public infrastructures is blinded out (

Shove 2010), while responsibility taking is shifted to private realms where lack of resources and infrastructures prevail (

Maniates 2002;

Hobson 2002). In this regard, various authors express concern that sustainable consumption could stabilize social inequality, since members of lower social income classes might remain excluded (

Barendregt and Jaffe 2014). Second, critics point out that the emphasis on citizens who fulfil their

duties contradicts empirically existing forms of ecological citizenship. These forms make use of citizenship

rights through participation in an environmental activism that puts state actors and the corporate world critically under pressure (

Kenis and Lievens 2014;

Seyfang 2005). Taking up these critiques, our reconstruction of sustainable citizenship will investigate the roles of infrastructural availability, socio-economic backgrounds, and citizenship norms, rules and values, which might be interrelated and attached to critical and participatory forms of (sustainable) citizenship.

2.2. Insights from Research on Political Consumerism

Research interest in political consumerism arose in the 1990s, when scholars pointed at rising tendencies of citizens to withdraw from traditional forms of political participation like active membership in political parties. Instead, citizens seemed to be turning to ‘lifestyle politics’ (

Bennett 1998;

Giddens 1991). This development included a rising number of boycott campaigns that citizens used to pressure firms, and the rise of labelling schemes (

Micheletti 2003). Gradually, questions were added to the standard question used in population surveys to measure political participation, asking respondents whether they partook in boycotts and/or buycotts (e.g.,

European Social Survey 2002;

Stolle et al. 2005). Increasing numbers of citizens who confirmed to engage in this political consumerism then also led to its general recognition as a stable participation form (e.g.,

van Deth 2014).

Political consumerism is the individual’s “market-oriented engagements emerging from societal concerns associated with production and consumption” (

Boström et al. 2019, p. 2). In other words, the ‘consumer-citizen’ is aware of the political embeddedness of consumption, and deliberately decides to buy or not to buy certain products or services for ethical, environmental or societal reasons and so to exert political influence. The citizenship model underlying this literature then is similar to Dobson’s conceptualization in three regards: the private is seen as political, citizens take responsibilities across borders, and they are driven by norms of solidarity. However, it stresses consumers’ ability to exert political influence and thus embodies an alternative conceptualization of sustainable citizenship (

Micheletti and Stolle 2012).

Sustainable citizenship as political consumerism has not yet been studied systematically with the help of quantitative data. A main obstacle is that the general concept of political consumerism is both broader and narrower than sustainable citizenship. It is broader as it considers a wider range of dispositional factors. Political consumerism can relate to a very wide range of intentions, including ecology but also, nationalistic or religious concerns (cf.

Stolle and Huissoud 2019). Simultaneously, it is narrower in its reliance mainly on one or two items regarding performances, namely buy- and boycotting. Only in a set of more recent studies, the range of practices considered is somewhat extended. In particular,

Micheletti and Stolle (

2008) suggest amending the definition of political consumerism to include

‘lifestyle choices’ and

‘discursive actions’. Lifestyle choices relate to the constancy and depth of the individual decision to incorporate responsible action and certain political values in daily life. Thus, they resemble those non-monetary practices on which the empirical research of Dobson’s model focused. Discursive actions refer to the public circulation and expression of individual opinions about firm practices and consumer culture, which can include the general critique of consumer culture. Hence, the conceptual expansion and newer calls to adopt the practice turn (

Oosterveer et al. 2019) capture the empirical complexity of political consumerism. Yet, these suggestions still await applicable measurement instruments and their general empirical assessment.

The main factors studied and shown to be distinctive among political consumers are socio-demographic factors, political values, purchasing criteria and institutional trust. In terms of socio-demographics, political consumers tend to be female, younger and more highly educated than the rest of the population (e.g.,

Acik 2013;

Copeland 2014a,

2014b;

Stolle and Micheletti 2013, pp. 68–71;

Newman and Bartels 2011). Also, political consumers tend to be affluent, but the difference in their incomes compared to non-political consumers is small in countries with high ratios of political consumers, particularly in Western Europe (

Stolle and Micheletti 2013, pp. 70–71). Besides, income seems to be important to different degrees for the different variants of political consumerism (

Koos 2012;

Zorell 2019).

Moreover, political consumers differ from the rest of the population particularly regarding their citizenship norms and political values. They tend to be left-leaning, postmaterialist and pro-environmentalists who value solidarity, equality and animal rights (

Copeland 2014b;

Goul Andersen and Tobiasen 2003;

Stolle et al. 2005).

Stolle and Micheletti (

2013, p. 89) observe that particularly the disposition to support people who are worse off than oneself is the most dominant norm connected to political consumerism. Furthermore,

Copeland (

2014a) compares support among political consumers of both dutiful and engaged citizenship norms. The former refers to key attributes of ‘good’ citizens (e.g., vote at elections, follow rules and laws, pay taxes), while the latter relates to active participation in politics and civic life (cf.

Dalton 2008a,

2008b). As Copeland finds, engaged but not dutiful norms relate to political consumerism and they differ in this regard clearly from the non-political consumer population. In contrast to Dobson’s understanding of citizenship, political consumerism thus empirically seems to rely on a rights-oriented model of citizenship. Correspondingly, various authors have pointed out its relationship with social movements (e.g.,

Holzer 2006;

Stolle and Micheletti 2013; see also

Boström et al. 2019) or its character as an

expressive mode of political participation (

van Deth 2014).

Similar to the research on sustainable consumption, scholars of political consumerism have examined purchasing criteria.

Stolle and Micheletti (

2013, pp. 87–88), for example, analyse four items on self- and other-regarding motivations that regularly guide purchasing decisions (see also

Zorell 2019). They find that political consumers are more than others driven by other-regarding motivations (acknowledging the responsibility for the consequences of own consumption, as well as ethical, political and environmental reasons that guide consumption choices). Nonetheless, they report performing their purchases out of self-interest to the same ratio as other citizens and seem to be even more price-oriented when buying products (

Stolle and Micheletti 2013, p. 87). Likewise, other studies corroborate their ethical, social, and environmental concerns, but also identify motivations such as health preservation as important drivers (cf.

Micheletti 2003, pp. 11–12;

Micheletti and Stolle 2012;

Stolle et al. 2005).

Lastly, despite a persisting view that political motivated purchasing is rather an apolitical, ‘feel-good’ pursuit of the public good (

Maniates 2002),

Stolle and Micheletti (

2013, pp. 85–88) among others, illustrate that political consumers are highly critical towards multinational corporations, whereas they do not distrust political institutions more than others. Similarly, in her U.S.-based study,

Copeland (

2014a, p. 183) finds that distrust in politics can marginally explain boycotting, but not buycotting (see also

Lekakis 2013).

In sum, boycotting and buycotting prove to be stable forms of action on the political participation repertoires across countries (

Stolle et al. 2005). They are distinct from each other (

Baek 2010;

Neilson 2010;

Zorell 2019), but frequently overlapping. The quantitative empirical enquiry into its related performances is yet narrow. Nevertheless, this research has identified a broad set of dispositional factors characterising political consumers: certain socio-demographic characteristics, political values, purchasing criteria and distrust in multinational corporations. These factors possibly accompany real-world sustainable citizenship. Therefore, we will include them in our subsequent reconstruction of sustainable citizenship.

3. Studying Sustainable Citizenship after the Practice Turn

Each line of research tends to model the boundaries of sustainable citizenship differently and before the empirical enquiry. However, theory and empirics need not necessarily be congruent. Thus, the question remains, where the boundaries of sustainable citizenship are drawn in practice if we assume sustainable citizenship to be one or more practices. To address this question, we suggest adopting a specific aspect of the practice turn.

Along with the critiques of Dobson’s citizenship model, several authors have suggested adopting the practice turn in order to elucidate the practical viability of sustainable citizenship (particularly

Shove 2010). While these works have yielded impressive insights in recent years (

Shove et al. 2012;

Denegri-Knott et al. 2018;

Evans et al. 2017;

Krogman et al. 2015;

Jaeger-Erben and Offenberger 2014), we want to emphasize that the practice turn offers yet another, so far neglected way to enrich the state of research.

Schatzki (

2008) points out that a practice is a two-sided phenomenon, like a coin: Practices can be studied either as stable social entities or as arrays of relatively similar performances. As a performed range of activities, a practice might appear rather changeable and scattered, since from this perspective, a practice is an empirically identified bundle of various individual actions, which are yet coherent enough to be categorized as a single practice. Most researchers deal with this aspect of practices.

Viewed as an entity, however, a practice consists primarily of a specific know-how or a practical rule of conduct. Besides competence, emotional evaluations or cognitive reflections of that practice in form of knowing what is good or bad about it and under what factual conditions it takes place, belong to a practice as an entity. The side of practices as entities thus is the level of skills in connection with specific material resources. Therefore,

Reckwitz (

2006) also calls practices as entities the dispositions which enable actors to perform a practice in a single, well-established way. Compared to behaviouralist understandings of individual attitudes, the concepts of a practice as an entity (

Schatzki 2008) or as the unique disposition to conduct a practice (

Reckwitz 2006) share an emphasis of the rather unconscious character of human conduct. Yet, in contrast to behaviouralism, they emphasize the social regularity of practices as entities or dispositions. Thus, this aspect of a practice is conceptualized as socially widespread, unique, and temporally enduring, whereby individuals cannot simply change voluntarily a practice in the sense of a widespread social entity.

However, most of the respective research following the practice turn focuses on the performances of related practices, their infrastructural underpinnings or their various cultural conditions and specific obstacles. The question, which unique, stable dispositional background empirically and relatively invariably enables and thus demarcates sustainable consumption or citizenship in the sense of a social entity remains neglected—or it is taken for granted with reference to theoretical ideals. Yet, empirically, various observations appear to be possible. There might be one or more practices understood as entities that should be identified as sustainable citizenship (cf.

Warde 2013, whose attempt to identify ‘eating’ as a practical entity concludes with the finding that it is a rather hybrid compound of several, interrelated practices).

To understand how sustainable citizenship as an entity needs to be identified, one should furthermore recall

Schatzki (

2008, pp. 91–110), who distinguishes “dispersed practices” such as describing, explaining or questioning, from “integrative practices” like farming, cooking or voting. Although both sorts of practices can be seen as stable social entities, the latter relies on a motivation to attain a specific goal such as to harvest, preparing a meal or building government, while the goals of the former vary greatly. For example, ‘explaining’ as a dispersed practice can be part of environmental activism, as it can be used to dismiss wars. Sustainable citizenship as a single disposition to perform a practice thus may foremost consist of various integrative practices, since only these are more specifically bound to certain temporally stable emotional reactions and goals. However, Schatzki’s concept of integrative practices is not precise enough because it omits values, whereas values are generally assumed to be central parts of sustainable citizenship.

Therefore, we suggest following Reckwitz cultural sociology as practice theory. It emphasizes that the disposition towards certain integrative practices enable a cultural group to distinguish their preferred lifestyle from others (see also

Evans 2019). Culture, here, is understood as a nexus of integrative practices that reproduces a certain way of life considered generally worth striving for. Hence, culture in Reckwitz’ sense, is about what kind of subjectivity is to be seen as virtuous and thus helpful to identify citizenship as the practical ideal of the good citizen. Related

cultural practices include a practical code and a related “schemata of interpretation and perception” (

Reckwitz 2006, p. 41), so that they distinguish ‘good’ from ‘bad’, and ‘us’ from ‘them’. Compared to Schatzki’s integrative practices, cultural practices additionally include values. From this perspective, purchasing is an integrative practice, but purchasing organically labelled products may qualify as a cultural practice in the sense of a practice that distinguishes sustainable citizenship. Hence, we can study if sustainable citizenship can be understood as a practical culture in the sense of an entity consisting of distinctive dispositions which motivate actors to perform certain key practices against the backdrop of certain values and worldviews.

The main methodological problem for identifying the entity side of practices in general and of sustainable citizenship as a practical disposition in particular, is that according to practice theory, this side of the coin consists of rather unconscious know-how or tacit knowledge. Therefore, the analysis needs to reconstruct the dispositions from the other side of a practice, namely its practical performances. Most importantly, this reconstruction needs to focus on possible ‘key’ cultural practices, since these key practices integrate usually larger networks of dispersed and integrative practices. In theory, we find, for example, that Dobson identifies a single key practice, the ecologically motivated downsizing of one’s ecological footprint, as the logical expression of one’s principal ethical obligation to act within the ecological boundaries of the earth. This practice supersedes but also connects its related integrative practices, like buying organic products.

Yet, from the viewpoint of the practice turn, it is also empirically possible that a cultural group is integrated by several alternative key practices. Moreover, the precarious connection between performed practices changes over time and space, so that the dispositional side changes, too (

Reckwitz 2006). The qualitative methodologies used to address this problem (see

Warde 2013) are not compatible with our purpose, since they ground on participant observation and hermeneutical interpretation. However, our approach shall be inspired, even if not guided, by Reckwitz’ practice approach. We envisage a methodological emulation of reconstructing the entity side through identifying interconnected and key practices at both performative and dispositional levels inductively. To do so, we apply statistical means (PCA) with the help of a radically extended horizon of possible practices, dispositions and their interrelations. This set of potential dispositions and performances we retrieve from the insights and items of the literatures discussed above. Using PCA, we can explore them for stable nexuses or patterns which we can interpret as the side of entities in order to identify the shape of sustainable citizenship as it is practiced and motivated by ‘real-world’ citizens.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Approach and Research Design

Scholars define and citizens practice sustainable citizenship, political consumerism or sustainable consumption in numerous diverging, at times politically contested, ways. This article’s main aim is to contribute in closing the resulting gap between ‘ideal and real’. Therefore, we intend to reconstruct which and how many forms of sustainable citizenship, in the sense of social entities, exist according to citizens’ (cultural) practices. Inspired by the practice turn, two main questions result: What is sustainable citizenship in terms of a widespread stable social practice as a social entity? And, second, which related practices empirically attain the status of key cultural practices, which distinguish themselves from other ways of life in terms of their goals, values and political attitudes?

With regard to the first question, a methodological problem is that practices do not necessarily speak for themselves, although authors like

Schmidt (

2015) stress this intention as practice turn’s main issue. As an alternative, we propose to apply a principal component analysis (PCA) to a wide, systematically assembled set of activities that might or might not be related in the sense of a practice. Hence, rather than pre-formulating a single, fixed definition of sustainable citizens’ ideal actions, what is needed is a broad pre-conceptualization that allows for discerning what real-world key practice appears to be a dominant pattern underlying respondents’ answers. This pattern may then be said to represent the practice of sustainable citizenship in the sense of a stable social entity that exists as a widespread and coherent disposition to perform related doings and sayings.

Sustainable citizenship is a multi-dimensional phenomenon, which can include purchases (in general or of singular product types, like food, clothes) or non-market behavior in everyday life. Furthermore, assuming a wide approach covers aspects spanning from acquisition, usage and disposal (

Fischer et al. 2017), as well as mobility, services and lifestyle choices.

To answer the second question, the factor variables allow us to divide the population into highly- and rarely-engaged in the related practices. This separation does not seek to identify essentialist groups of ‘sustainable citizens’ and ‘others’. Instead, it permits us to reconstruct the stable dispositional side that may accompany the identified practices of sustainable citizenship, and the distinctive values, attitudes and meanings which the dispositional side attaches to the practices. Again, our intention is to widen the range of possible dispositions. Whereas research on ecological citizenship looks for ecological values, the literature on political consumerism focuses on political attitudes and socio-demographics. Some works furthermore investigate purchasing criteria. The resulting range of items that possibly are part of sustainable citizens’ dispositions exceeds practical limits. Our lens from the theories of cultural practices permits us to concentrate on four sets of items.

According to

Schatzki (

2008), the core of each social practice is a stable rule of conduct. Therefore, we make use of a set of items which comprise self- and other regarding purchasing criteria, including taste, health-orientation, ecological and social criteria. Moreover, we consider motives like distinguishing oneself from others or relevance of infrastructural availability. With regard to Reckwitz’ emphasis on cultural practices coming with group-related repudiations and appreciations, we further incorporate items on trust in relevant institutions (government, multinational corporations and environmental organizations). Trust hereby also stands for a practically guiding emotion in Schatzki’s sense. In a similar vein, we include several items on citizenship norms. This way, we can examine which general political values respondents attach to their practices. Finally, and with regards to problems of social bias, we will consider socio-demographic items.

4.2. Data in Use

In 2014, we conducted an originally designed survey among a representative sample of the citizens in Germany. The survey and questionnaire were guided by a dual purpose: assessing the prevalence and frequency of various ecological and political consumption activities; and discern links between activities and certain values, perceptions of civic rights and duties, online media use and shopping habits. Accordingly, the survey covers the range of variables we need. Therefore, we use its data for our analyses.

Following two pre-tests, we recruited respondents from the German online panel of the research institute respondi (Cologne).

1 The sample was intended to mirror the general distribution of the population in Germany according to three central socio-demographic parameters: age, gender and education. The German Microcensus 2012 served for establishing corresponding quota.

2 The goal was to get a sample that allows for examining our assumptions without major distortions in age, gender and education, since extant research points to clear influences of these three demographic variables on ecological citizenship and political consumption. Previously set quotas for each combination of age, gender and education level (i.e., ‘stratum’) demarcated the maximum number of individuals that each group should include, whereby the inclusion of each stratum should be secured. This set-up lets us test our assumption that sustainable practices vary systematically across cultural milieus, rather than having to attribute variances to distortions in the general population statistic (e.g.,

Rea and Parker 2014).

After adjusting the data set for invalid responses

3, the sample covers 1350 respondents.

4 The sample distributions effectively mirror the German population as it was recorded in the 2012 Microcensus: the distribution of gender is identical, the age groups and education levels are, overall, very well reflected, too. There are only some discrepancies related to education and to age. Therefore, for the descriptive tables, we apply one combined weight for the three indicators.

5 5. Identifying Sustainable Citizenship Based on Practices

Our approach relies on the assumption that sustainable citizenship in the real-world is grounded on stable and widespread key practices. This leads us to three central expectations. We expect that, first, several integrative practices, such as buycotting or sharing goods with others, are interconnected and form one or several empirically coherent bundles representing a key practice. Second, each key practice can be attributed a common rule of conduct regarding how to perform sustainability. Third, we expect that they are performed by a recognisable number of people in a population. Respectively, we need to look at a broad set of integrative practices that can be performed in more or less sustainable ways, and be combined or not. Taking into account the different lines of theory, this should cover monetary and non-monetary lifestyle activities which occur regularly.

In line with this need, the survey includes an extensive set of items that address deliberate and regular engagement for social or ecological reasons—sustainability-related motivations—in several shopping and consumption activities. It covers three items that are used within the literature to measure political consumerism (boycotting, buycotting products, buycotting companies), six items referring to resource-saving lifestyle practices (consume generally less, do without meat, share goods with others, re-use as much as possible, purchase second hand, give advice to others), and two items concerned with mobility (using public transport instead of a car and walk or take bicycle instead of a car). Our aim at this stage of the research was to widen the perspective to various possible practices that might turn out during further analysis as related to sustainability. Therefore, this measurement does not focus explicitly and exclusively on pre-defined sustainable behavior, but on common everyday behaviors that can be performed in more or less sustainable ways.

To examine if and how these activities are interconnected without relying on prior assumptions, we apply an oblique data reduction approach (PCA) in which items can load on more than one component and components can be correlated.

Table 1 shows the results with a satisfying three-dimensional solution. The values are the correlations between each item (row) and the components (column), thus showing what the components represent. A first component grounds mainly on the three political consumption items but also includes avoiding the consumption of meat. A second component unites the two mobility items. The third component includes five items relating to resource-saving forms of sustainable practices. Two items—to consume generally less and to give advice to others—load on the first in addition to the third component. Reliability tests suggest including them as part of the two. Apparently, consuming less and advice-giving are part of the two types of sustainable citizenship practices, thus underscoring the thought that two people may have a same motivation or goal (i.e., to act sustainable), but translate that into different sorts of actions. Thus, we include these items within the two dimensions.

In line with the first expectation, these results show that sustainable citizenship consists of at least three key practices. The first component can be interpreted as the key practice of sustainable purchasing, which includes boy- and buycotting, but also, the lifestyle practices of consuming less and avoiding meat, and the discursive practice of giving advice to others. Component 2 suggests that a second key practice unites walking, cycling and using public transportation in the sense of sustainable mobility. The third component can be regarded as a form of reduced consumption, as it includes activities like re-using as much as possible, sharing goods with others and purchasing second-hand. For clarification, at this point, these practices are sustainable in effect rather than exclusively by intention, although below, we will show that they are also backed by ecological motives.

The items of consuming generally less and advice giving load on both components 1 and 3. Both items are declared by

Dobson (

2003) as the most important practices, namely downsizing the individual ecological footprint and spreading the word. Likewise, consuming less meat (loading on component 1), acting resource saving (as captured, e.g., by re-using goods, loading on component 3) and walking/cycling/using public transport (loading on component 2) are all generally acknowledged as key practices for sustainability. At first sight, these results support existing strands of research. Sustainable purchasing appears to be a practice of political consumerism that aims at influencing existing value chains. Reduced consumption resembles those indexes made with reference to the ideal of ecological citizenship. However, PCA also shows intriguing deviances from existing assumptions. With regard to Dobson’s pledge for reducing ecological footprints and engaging in educational activities, the two items of consuming less and giving advice to others are not only part of reduced consumption but also of sustainable purchasing. This suggests that sustainable purchasing combines the practical aim of changing value chains with spreading the word

and downsizing production and consumption in general. While sustainable purchasing and reduced consumption appear to be distinct, they seem to overlap in these two central practices of ecological citizenship. This also confirms our second expectation.

However, the boundaries of the three key practices are not identical with theoretical demands. Avoiding meat as a lifestyle choice, for example, is linked to sustainable purchasing, while buying second hand as a form of purchasing belongs to reduced consumption. A possible interpretation of this is that sustainable purchasing stands for making greater efforts to change, e.g., spending more money or giving up meat, while the practices of reduced consumption centre on re-arranging what is already owned and routinely done. Furthermore, and in contrast to existing measurements of pro-environmental behavior of sustainable citizens, sustainable mobility differs from the other two key practices since it does not cover the items of consuming less and spreading the word. Thus, its performance appears to be another, independent form of actualizing sustainable citizenship. This finding indicates support of

Shove’s (

2010) assumption that mobility practices are foremost determined by traffic infrastructures and less-so related to Dobson’s idea of citizenship, which makes it a rather private matter and its adoption dependent upon the particular circumstances.

In order to examine whether the three key practices are widespread in use, we construct indexes using the means of additive scales weighted by the number of items loading on each component.

6 Consistent support of items loading on each of the components can be seen as indication of a distinct form to put sustainability into practice. Hence, each index measures the degree to which a respondent performs the respective component as a key practice of sustainable citizenship. The scores range between zero and one.

Table 2 gives an overview of the descriptive statistics. About 37.0% show high engagement in the market-based sustainability practice and in sustainable mobility, whereas 53.4% of the individuals show above-average engagement in reduced consumption. Furthermore, the results from the PCA show that sustainable purchasing and reduced consumption include the same rule of conduct with regard to consuming less and spreading word. To examine whether the two practices tend to be combined and practiced by the same people or not,

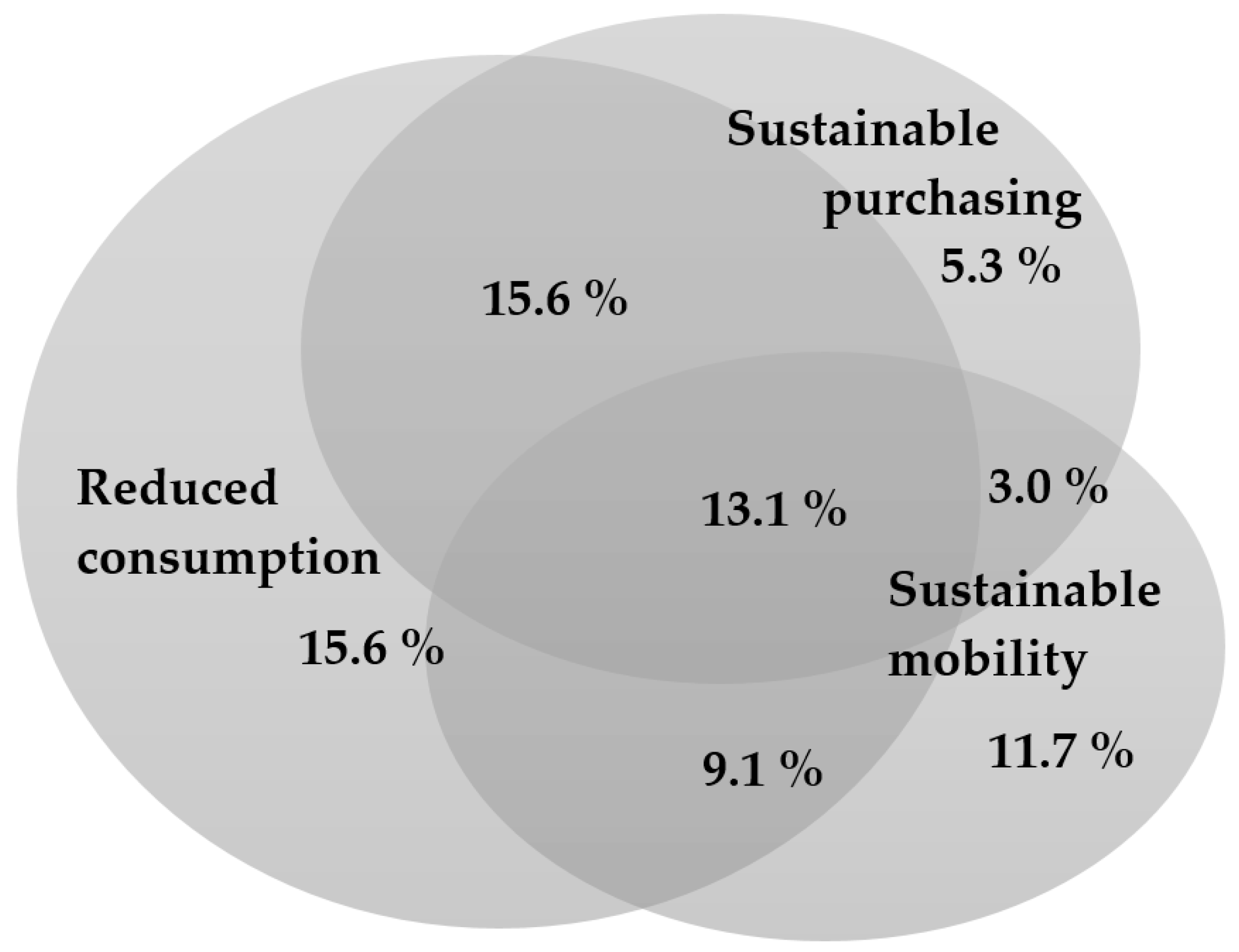

Figure 1 considers to what extent sustainable purchasing, mobility, and reduced consumption above average overlap. The three circles cover the space of the 73.4% of respondents who are at least in one key practice engaged above average.

While 53.4% of the respondents are highly engaged in reduced consumption, 37.0% and 36.9% score above the mean of engagement in sustainable purchasing and mobility, respectively. However, only 13.1% of the respondents apply all three key practices above average and at the same time. This result stresses the finding of the PCA according to which the three key practices of sustainable citizenship occur rather independently from each other. This illustrates a gap between the ideal set of sustainable citizenship’s practices and the real-world pattern. While it is unsurprising that some respondents engage more in sustainability and others less,

Figure 1 shows that the resulting variance appears less to be a continuous deviance from a single ideal set of practices, but rather, that it has a specific pattern.

The distribution of the overlapping intersections between the practices is not symmetrical. Reduced consumption is more widespread and it is performed to a higher extent without at the same time purchasing sustainably (24.7% in total, not displayed) than the other way around (5.3% without plus 3.0% with sustainable mobility). A total of 15.6% perform these two practices but not sustainable mobility above average, 13.1% perform all three above average. Overall, sustainable purchasing is mostly combined with other practices, a finding which corrects a widespread view that sustainable purchasing is a way to ‘feel-good’ and to buy a good conscience while abstaining from other actions. In contrast, reduced consumption and sustainable mobility seem to be more independent as they intersect only in parts with any of the other key practices.

This asymmetrical pattern can be interpreted in terms of sustainable citizenship as a practiced entity. The key practice with the highest degree of intersection within this pattern is sustainable consumption, while reduced consumption is the more widespread. Finally, sustainable mobility is the most distinct from the other. Thus, it can be concluded that—similar to Warde’s notion of eating as a compound practice—sustainable citizenship is a hybrid, compound nexus of three, asymmetrically interrelated key practices.

6. The Dispositions of Sustainable Citizens

6.1. Socio-Economic Indicators of Sustainable Purchasers and Green Housekeepers

Various authors have stressed that the performance of sustainable citizenship is restrained by socio-economic factors. So, for example, political consumers tend to be more often female, well educated and affluent. In order to examine to what extent these factors explain engagement in each of the three practices, we look at gender, education, age and social class.

Gender is measured as female = 1 and male = 2.

Age is measured in age groups through eleven categories, starting with 14–18 (coded 1), 19–24 (2) and from there, moving in five-year steps up to 69 (coded 11).

Education is assessed through five categories, asking for the highest degree completed. This includes the option of indicating when having no degree or not yet (coded 1), three levels of school leaving certificates (equivalent to 9, 10 or 13 years of school; coded 2, 3 and 4, respectively) and holding a university degree (5). Finally, one question addresses subjective

social class belonging by means of three categories, lower, middle and upper class (coded 1, 2 and 3, respectively).

Table 3 shows the respective results.

The findings in

Table 3 support existing research insofar as sustainable purchasing and reduced consumption tend to be performed by high-educated females. Age differences are, in turn, decisive for the tendency to being engaged in sustainable mobility. Those who are engaged in it are younger than those who are not.

7 Furthermore, a higher-class position significantly relates to sustainable purchasing, whereas reduced consumption and sustainable mobility seem to be performed slightly more by people from a lower social class, yet not to a statistically significant extent. This irrelevance of class position supports the previous interpretation of reduced consumption and sustainable mobility as low-threshold practices, especially compared to sustainable purchasing.

6.2. Purchasing Criteria

Social class position and age help understanding why sustainable citizenship in the ‘real-world’ is hybrid and consists of three rather than one single key practice. However, a resultant lingering question is whether this also means that they are three rather than one form of sustainable citizenship. A comparison of the purchasing criteria that are important to those people who engage in each of the three practices above average allows for addressing this question. Our main assumption is that for the delineation of a practice, it is central to identify the underlying rules of conduct as part of the dispositional side at which practices exist as unique entities. In other words, those who perform these three key practices above average can be seen as being more versed and experienced in their conduct. Hence, a comparison with those being below average engaged in the key practices will reveal which purchasing criteria are decisive for these practices as unique entities.

The survey includes an original set of such items tapping into the practical criteria that guide respondents’ shopping choices. The respondents were invited to assess, on a seven-point scale, the extent to which they perceive nine aspects as being (−3) not at all important to (+3) very important criteria when deciding what to buy. After the survey, the items were recoded into scales ranging from 1 to 7. The items cover the questions if a purchase must be conveniently available, tasty/well-suiting, inexpensive, good for one’s health, and presentable in a circle of friends. The first of these items indirectly covers problems of infrastructural availability, whereas the last item was included to examine the importance of achieving social distinction through consumption practices. Next to these self-regarding practical rules, data on other-regarding criteria were gathered. Related items asked whether respondents followed the rule to buy products that are produced under fair working conditions or that are considered as environmentally friendly.

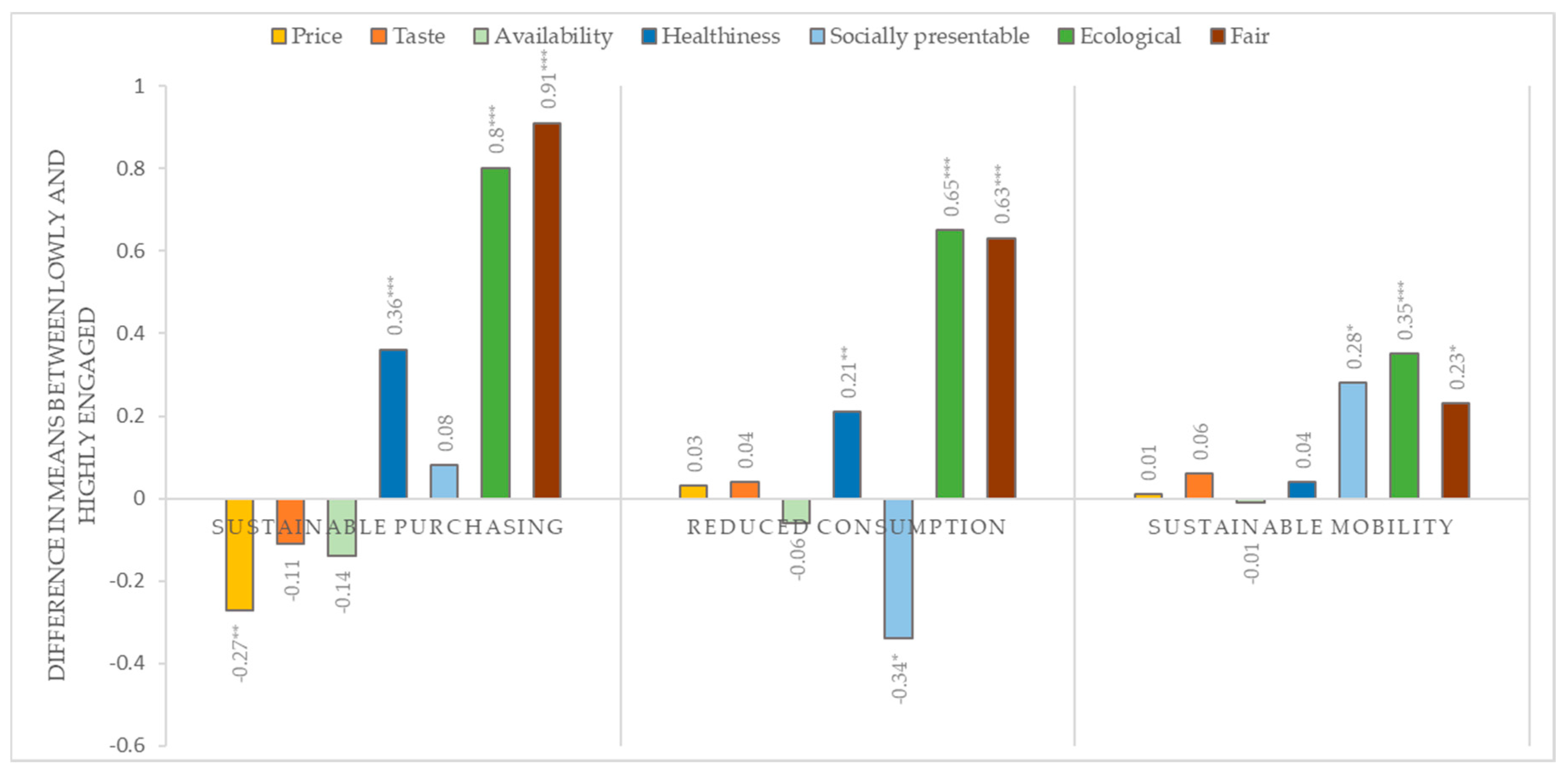

The values in

Figure 2 depict the differences in means between those who score high and those who score low on each of the three practices. Positive values indicate that highly engaged respondents rely on a purchasing criterion more heavily than those who perform the key practice below average. Negative values indicate the reverse. Overall, sustainable purchasing and reduced consumption are associated with similar practical purchasing rules. The two practices are related to looking for healthy, ecologically and fairly produced products. However, the two differ from each other in that the former is associated with little importance of price, while the latter with low attribution of importance to what others think. This also fits in with the results from

Table 3, altogether suggesting that economic resources explain the different translation of similar values into distinct practices. Reducing purchases is economically more easily accessible, while it can also demand a certain degree of emancipation from trends and peers’ opinions. Sustainable mobility, too, is linked to the purchasing criteria of selecting ecological and fair products, while it is also more closely related to socially presentable purchasing decisions.

Finally, the findings contradict two frequent critiques raised about ecological citizenship. The unavailability of products through lack of infrastructures and the need for social distinction through the consumption of certain products are often suggested to inhibit ecological citizenship. However, the results do not confirm this pessimistic view. Only sustainable mobility is linked to attributing importance to the social representability of purchases. Other than that, the respective criteria seem to be of no other importance to those engaged in the key practices above average than to the rest of the population.

6.3. Norms of Sustainable Citizenship and Trust

A further part of our enquiry concerns what norms the three groups of sustainable citizens refer to. To cover the norms of citizenship regarding solidarity, engagement and the fulfilment of duties considered in earlier studies on political consumerism, the survey covers the standard set of items to measure norms of citizenship as developed by

Dalton (

2006), expanded by a few items from the Swedish Citizenship Study 1998 and the Citizenship, Involvement, Democracy Survey 2001 that seem to be more appropriate for the European context (

Denters et al. 2007;

Petersson et al. 1997). In total, the respondents are presented nine statements and invited to assess if for being a ‘good citizen’ the aspects are, on a seven-point scale, (−3)

not important at all to (+3)

very important:

Always vote in elections

Never try to evade taxes

Be active in voluntary organizations

Be active in politics

Support people in Germany who are worse off than oneself is

Show solidarity with people in other countries who are worse off than oneself is

Choose products taking care of social and environmental aspects

Be prepared to break a law when the own conscience requires so

Not wait for the state to solve the problems but take own initiatives

Again, the main motive was to explore inductively how these norms of citizenship are distributed within the dataset. Using an orthogonal data reduction approach (PCA) reveals in total three components (see

Appendix A,

Table A1). The first component includes solidarity with people worse off than oneself in Germany (item 5) and elsewhere (6), eco-fair purchases as part of good citizenship (7), and the norm of engaging as a private person for the common good instead of shifting responsibility towards the state (9). It thus resembles both Dobson’s and Micheletti’s ideas of private responsibility-taking, which is inspired by norms of solidarity or fairness. The second component covers the norm to participate in elections (1), voluntary organizations (3) and in politics generally (4). Hence, it can be described as a norm of political engagement. Finally, a third component unites the norm to pay taxes (2) and to obey existing laws (8, reverse coded). This matches the idea of good citizenship in terms of duties and as expressed through loyalty to secure a stable social order.

The components were transformed into three additive indexes weighted by the number of items whereby each index ranges from 0 to 1. Higher scores refer to higher support for the respective sort of citizenship norm. Respectively, we label the indexes “Solidary Citizenship”, “Duty Citizenship” and “Engaged Citizenship”.

8 Table 4 presents results from comparisons between respondents who are lowly and those who are highly engaged in sustainable purchasing, mobility and reduced consumption, respectively. Again, the logic of these comparisons rely on the assumption that we can learn about the inherent driving motives of the three key practices if we ask for the distinct citizenship norms of those who perform these practices more intensively.

The figures in

Table 4 show that, in contrast to Dobson’s ideal of ecological citizenship, the conduct of the three key practices among highly engaged respondents does not relate to comparable citizenship duties. Nonetheless, they appear to be an expression of Solidary Citizenship. These results at least resemble Dobson’s idea that fairness among humans and the environment should be an integral part of sustainable citizenship. Furthermore, sustainable purchasing, mobility and reduced citizenship are significantly related to norms of Engaged Citizenship, which are stressed by the political consumption literature. Overall, the relationships of sustainable citizenship with engagement and solidarity norms parallel studies considering their links to political consumerism (cf.

Stolle and Micheletti 2013). The results suggest that sustainable citizenship, as it is practiced in the ‘real-world’, is normatively quite coherent, although adoption of the corresponding practices varies with relation to social class and age. Similar to political consumerism, sustainable citizenship as consisting of related purchasing, mobility and reduced consumption is usually driven by Solidary and Engaged Citizenship among those who perform these practices above average.

This interpretation that sustainable citizenship compares to political consumerism is further supported by findings on trust in institutions (see

Appendix A,

Table A2). The levels of trust in various institutional actors follow similar patterns across the three practices. Those who perform these practices above average tend to trust environmental institutions more than others do. To a lesser degree, they trust consumer associations, family-owned business, and farmers, while they strongly distrust multinational corporations. In general, trust in government does not differ between those who are highly or lowly engaged.

7. Conclusions

The aim of this article was to identify the real-world shape of sustainable citizenship and to gain a deeper understanding on what it is grounded. Inspired by the practice turn, the key argument was that by approaching sustainable citizenship with an open mind rather than testing a model fixed beforehand, we can broaden the perspective and prevalent understanding noticeably. Our results draw on data from a representative population sample surveyed online in Germany in 2014. Our main finding is that citizens practice sustainable citizenship through singular and relatively coherent types of activities, yet at the same time, through different forms of practices.

In the sphere of sustainable consumption, we identify two practices: sustainable purchasing and reduced consumption. Furthermore, we identify a third practice related to sustainable mobility. Each of these practices involves a confined and consistently related bundle of activities with a single core disposition that includes a rule of conduct, citizenship norms, and the emotional side with attitudes of trusting or distrusting certain institutions. Moreover, they are related to distinct socio-demographic backgrounds, namely gender, age and education. Social class matters only for sustainable purchasing. Simultaneously, we observe that the degree to which a person endorses norms of sustainable citizenship and the importance of sustainable purchasing criteria is high across all three forms of practices.

Sustainable citizenship is a nexus of several practices and as such, a larger phenomenon than supposed by earlier conceptions of pro-environmental behavior within the ecological citizenship literature. This misconception can be explained by their exclusion of the political motivation behind the influencing of value chains through buy- and boycotting. In fact, in contrast to prevalent assumptions within the literature on ecological citizenship, especially political consumerism appears as a form of highly committed change making, enabled largely through education, just as emphasized by ecological citizenship scholars.

Also, the result supports recent theoretical suggestions to expand the concept of political consumerism to material lifestyle practices. This research can particularly benefit from the inclusion of reduced consumption in their study insofar as this practice seems to correct for a central problem: the engagement bias towards economically better-off citizens, which is often brought up as a major critique against recognizing political consumerism as a political rather than market-consumer activity. Our results show that citizens from all social backgrounds practice sustainable citizenship and not only the rich. Yet they do so through different forms of practices, adjusted to their capabilities.

Narrowing down sustainable citizenship to foremost ecological citizenship then seems to be a theoretical rather than a practical option. Social and ecological concerns appear to be densely intertwined. The coherence of the dispositions underlying especially reduced consumption and sustainable purchasing stresses the interpretation that there is mainly one empirically dominant form of sustainable citizenship, in the sense of a practically and normatively integrated culture of shared practices. Sustainable citizens, regardless of whether they apply practices of reduced consumption, sustainable purchasing or sustainable mobility, follow practical rules of choosing ecological, ethical and healthy variants. Through this, they act as engaged citizens who try to contribute to social-ecological change through private and material practices, and who hereby express norms of solidarity.

Thus, contrary to various points of critique against sustainable consumption and ecological citizenship, the cultural meaning of the three practices stresses that sustainable citizenship in the real world shows more affinity to environmental activism than to the corporate world. This is also in line with extant research on political consumerism. Hence, it may be less seen as (mainly) driven by universal obligations to do one’s bit as a citizen, but as a form of political participation connected to a political culture which emphasizes the actively engaged, critical citizen. Nonetheless, as the separated practice of sustainable mobility and the roles of socio-demographic factors advise, enabling infrastructures and social dynamics are decisive, too.

Our results capture sustainable citizenship as it is empirically practiced among a representative sample of the population of Germany in 2014. Certainly, this temporal and spatial limitation recommends careful interpretation. Also, future studies may add more items to measure practice-theoretical elements, such as the practical rules that guide not only purchasing but also reduced consumption. Nevertheless, our results presented here can be understood as one further step contributing to gradually grasping more accurately the state of sustainable consumption as people practice it—and to the scholarly debate about what models of sustainable citizenship can serve as feasible means to meet the great challenges of our times.