“Continents and colors do not emigrate, but rather people and their cultures do. What was once local is now global and FGM/C is in diaspora.”

1. Introduction

Migrations pose political and ethical challenges in managing flows of people who change or want to change their country of residence, and in the strategies they seek out to achieve this. In this context, it is necessary to understand in what way cultural practices migrate with people, and whether and how the ideas of new learnings that take place through their adaptation processes are transferred to the communities of origin. “The experience of immigration entails an avalanche of new life situations which compromise and challenge values, shake the limits of loyalty to one’s origins, and open up a new internal, incessant and intense dialogue between conflicting options and alternatives.” (

Kaplan Marcusán and Bermúdez Anderson 2004).

Taking this as a frame of reference, this study focuses on the analysis of female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) as a traditional harmful practice, within the processes of identity resignification and selective acculturation that take place in the migratory context between The Gambia and Spain. Through this practice, deeply rooted in culture, which is transferred through migratory movements, we seek to understand how transnational relations articulate and impact information flows and decisions by people, both in the countries of origin and destination.

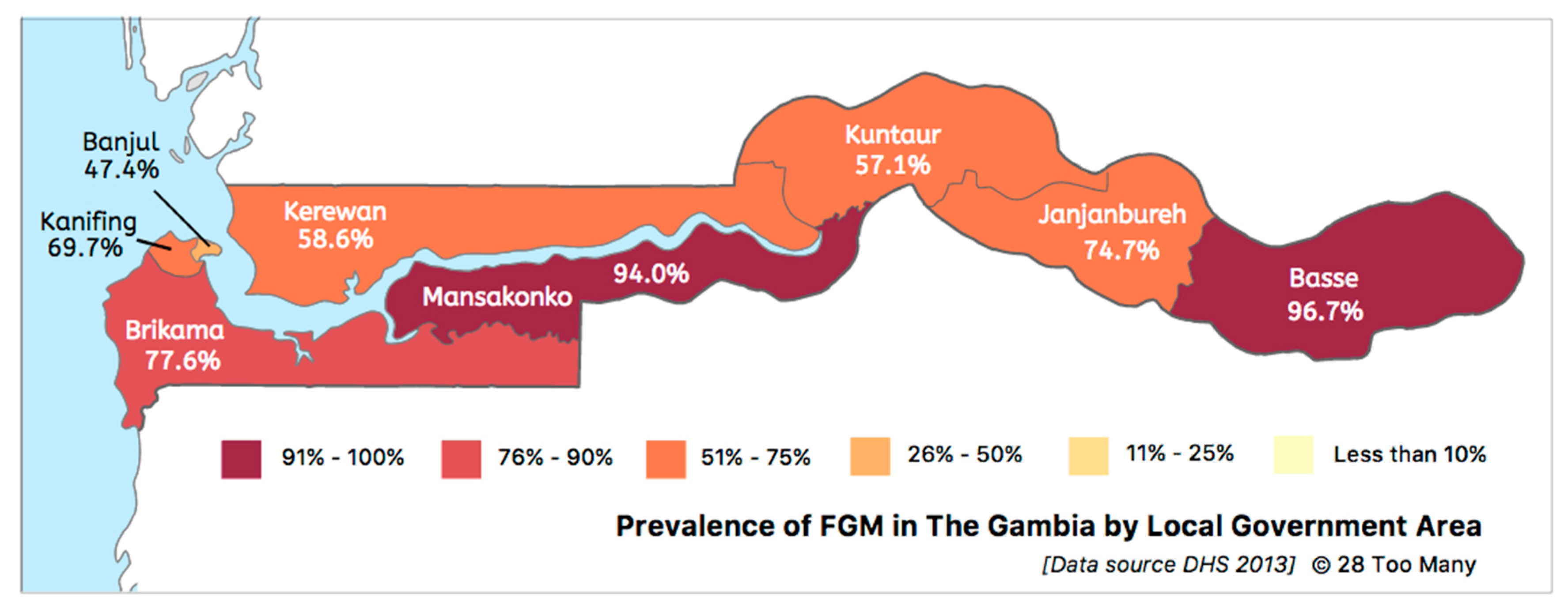

In The Gambia, the prevalence of FGM/C is 74.9% (

DHS 2013), ranking at number ten worldwide. As the map in

Figure 1 shows, the most significant differences are due to ethnicity and they occur between regions, due to the presence of different ethnic groups, as between the Serahules and the Mandinkas the prevalence is more than 95%, but among the Wollof it is less than 15% (

Unicef 2011).

According to the Map of Female Genital Mutilation in Spain 2016 (

Kaplan Marcusán and López Gay 2017), there are 69,000 women who come from countries where FGM/C is practiced, of which more than 18,000 are girls under 15 years old. Thirty percent of this population resides in Catalonia, being by far the autonomous community with the largest female population of this origin; followed by Madrid (12.9%) and Andalusia (11.3%). The proportion is larger when we look at the age group under 15 years old, which is 34.2% of the total number of girls of these origins officially registered in Spain (

Kaplan Marcusán and López Gay 2017).

The presence in Spain of girls at potential risk of having FGM/C carried out on them makes it essential to have a multi-sited approach to this phenomenon.

2. Objectives

The general objective of this study is to analyze the influence of migration on the practice of FGM/C. With this purpose in mind, the following specific objectives are laid out:

To understand the transnational relations that are established through migratory processes and the articulation of decision-making in a multi-sited space.

To evaluate the transnational impact of awareness-raising tasks both at the place of origin and at the destination.

To know the arguments and strategies used by migrant families to prevent FGM/C, both at the place of origin and at the destination.

To observe educational and socializing practices used by migrant families and their influence on intergenerational relations.

3. Conceptual Framework

Migration is a topic that has been researched extensively. However, there are relatively few longitudinal studies that offer an overall vision of the evolution of the transnational space. The first to carry out a multi-sited study between Spain and Senegambia was

Kaplan Marcusán (

1998) in her doctoral thesis. She took this characteristic of migratory movements and developed it as a study methodology.

Circular migrations are movements of people between one country and another, which can be permanent or temporary, and in these processes, people modify their lifestyles including the cultural elements of the countries of origin and destination (

Newland 2009). Circularity does not necessarily require a physical process of going to and from, but is linked to the construction of a transnational space as the basis of migratory chains and, as

Skeldon (

2012) explains, “in more recent times, electronic and other forms of communication reinforce these transnational linkages and allow them to exist and persist without direct physical movements.”

The transnational space is not only physical geography, but also all those intangible elements that compose our worldview (

Jackson et al. 2004). It is a complex sociocultural space, in which migrants straddle dualities and choose different strategies to reconcile an increasingly globalized way of life, and the ties with their countries and cultures of origin, which often pressure them to provide emotional and economic support (

Levitt and Jaworsky 2007;

Kivisto 2016;

Belford and Lahiri-Roy 2018). It includes “not only the material geographies of migration [...], but also the symbolic and imaginary geographies through which we try to make sense of our world”, it is a “complex, multidimensional and multi-inhabited space” (

Jackson et al. 2004).

Belford and Lahiri-Roy (

2018) suggest that we rethink the concept of transnationality as an area of epistemological research “including questions of identities and subjectivities as encrusted with sociocultural practices, and reconfiguration of existing relationships with family and friends.”

As

Berry (

1997) argues, the migratory process varies on different factors, but mainly, we can distinguish between five different stages (

Sluzki 1979), although they do not always develop in the same linear sequence. The first is the decision-making of the migrant and their family or community, which, in some cases, can be considered a survival strategy for the family as a whole (

Kaplan Marcusán 1998). The second corresponds to the geographical route which can be direct or carried out over several years until their desired final destination is reached. The third phase, called the overcompensation period, refers to adaptation. During this stage, the objective is survival; conflicts and tensions remain underlying, making it possible to maintain the norms and values followed in the country of origin.

The fourth phase, the decompensation or crisis period, occurs when the migrant nuclear family reformulates its new reality. Following

Berry (

1997), in this acculturation process, there are four adaptive strategies: (a) segregation, where the group consider maintaining its identity and do not establish relationships with the larger host society; (b) assimilation, when the group changes the traditions of the country of origin for the cultural practices of the host country; (c) integration, when the collision of both cultures results in the production of a new way of life; (d) marginalization, when the group refuse both, the initial identity and the relations with the host society.

In the particular case of FGM/C,

Johnsdotter (

2007,

2018) describes its practice as a strategy for securing the future well-being of their girls in their cultures of origin. But when they migrate to a new context where the practice is stigmatized and counter-normative, they have to revaluate its convenience, depending on the acculturation strategy chosen by the family.

In this process, the identity of the migrants is debated in three ways: (a) between the resistance of the religious and cultural values of the society of origin, maintaining traditions as links to the communities of origin; (b) between the transgression of values in relation to the culture of origin, where new practices and roles appear in response to old dilemmas; and (c) between the production of new adaptive strategies around central issues such as nutrition, sexual and reproductive health, and intergenerational relationships, among others (

Kaplan Marcusán 1998).

The fifth phase is the development of intergenerational shock, which occurs when the second generation of migrants establishes new links with the societies of origin and destination, re-defining their identity. In many cases, the confrontation is not only between generations but also between the group of reference and the group of belonging, in cultural, moral, and social terms.

Consequently, cultural identity is defined as a process under constant development, instead of essential characteristics of people. It is connected to the concept of acculturation, understood as the set of “cultural adaptations that people develop, produced by dissemination, borrowing, abandonment, transformation and creation of cultural elements and complexes and their relationships to each other, in a situation of contact and of accommodation to new conditions.” (

San Román 2006). “Acculturation turns out to be selective and dependent above all else on the needs and stimuli of social integration and social mobility” (

San Román 2006). In the particular case of FGM/C in the diaspora, studies such as that by

Johnsdotter (

2018) show that “migration from countries where FGC is practiced to countries where it is not customary, and even illegal, leads to cultural change and declining support of this practice in these groups.”

4. Methodology

In this work, we use a circular methodology to study the transnational sphere. This includes multi-sited ethnography which, over the last few years, has become “a central means for studying the linkages, exchanges, and feedback effects that circulate between two or more sites.” (

Fauser 2018).

This specific research was carried out in the transnational space between Spain and The Gambia during a period of three years between 2016 and 2019. Following the proposal of

Fauser (

2018), the links across borders have been monitored to study the practices and perspectives of migrants and non-migrants from both sides.

The qualitative methods used are based on the analysis of the phenomena in their natural context, interpreting the meanings that people give to them. For the design of the qualitative research, three basic principles have been taken into account: flexibility, reflexibility, and circularity. The design was open and adapted to the unexpected study situations. The constant reflection during the execution of the project facilitated the specification and development of the research, always taking into account that each phase can change the previous one and the next one, in a process of constant interrelation.

Twenty-five sensitization activities developed by the research team constitute the participatory methodology of the study.

In Spain, four workshops were held for migrant women, three for mixed young migrant people or “second generation”, and a session with mothers focused on the socialization and education of adolescent sons and daughters. Apart from that, the ongoing training of professionals from different fields carried out by the entity is also part of the process of empowerment and transfer of knowledge.

In The Gambia, the training sessions carried out in the selected villages have been divided into three groups. The way of approaching the community is essential and the existing hierarchy must be taken into account. For this reason, raising awareness should begin with the community and religious leaders who give their approval for the training of groups of men and women in the community. These sessions are intended to provide information on FGM/C to promote its prevention and improve attention concerning its consequences for one’s health, while contributing to skill development and community empowerment. The sessions were carried out by the training team over three days in each village. The facilitators of the activities were migrants who have been involved in raising awareness within their communities of origin, travelling with their families to The Gambia to organize, contact attendees, and coordinate the logistics of the sessions.

Two information gathering techniques have been used that allow participants to provide a voice: seventeen in-depth interviews and twelve focus groups, where the interactions and debates that occur in a group are analyzed, in order to find out the construction and exchange of opinions. With the interviews, the discourses and personal experiences of the migrants have been studied, as well as those of some of their relatives in The Gambia.

Finally, the data triangulation technique has been used to analyze the discourses and debates present in the communities and go more in depth on the relationships established at the transnational level. Then, the interviews and focus groups were transcribed and the information was codified and analyzed, using the qualitative analysis software QRS Nvivo 12 and Atlas.ti.

The sample was taken by following the criteria of matched sample (

Fauser 2018), that is to say, seeking out informants in the different geographic areas which are connected to each other, with the objective of studying the links, practices, and transnational exchanges that occur across borders.

For the selection of the participants in the study, the socio-demographic characteristics of the people being interviewed have been taken into account. Ethnic, gender, and age diversity have been considered, in order to be representative of the discourses, meanings, and opinions surrounding the FGM/C phenomenon, as well as the transnational relations of migrant Gambian society.

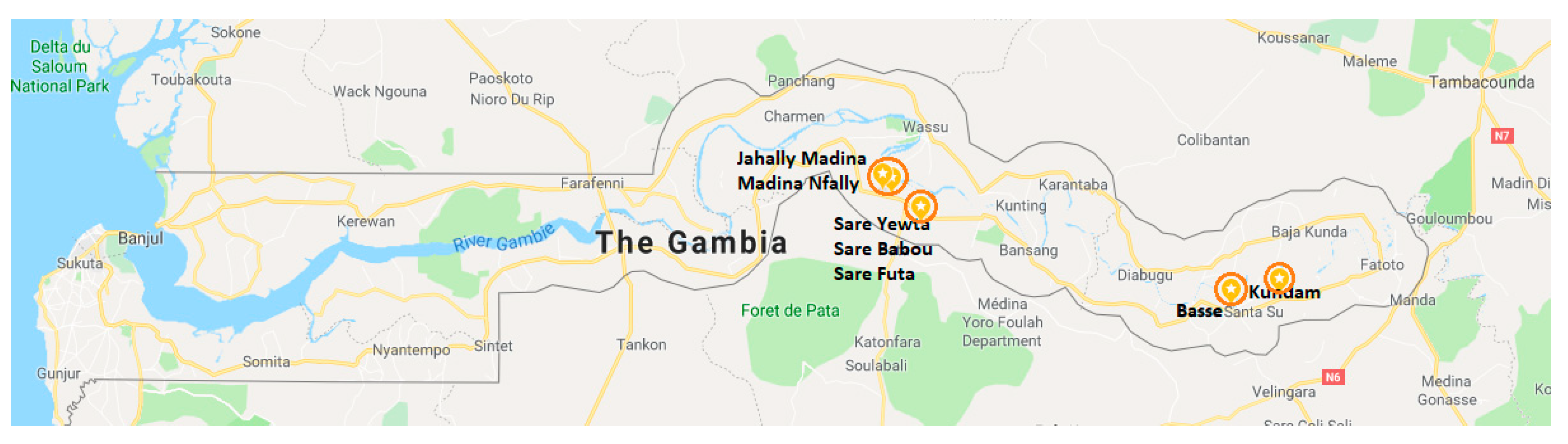

The analysis unit is based on migration and the transfer of knowledge between family members residing in different countries, while the observation unit is made up of immigrant communities and second generations in Spain coming from African countries where FGM/C is practiced and who reside in Catalonia. In The Gambia, field work was carried out in communities which had family members abroad, from villages in Central River Region (CRR)—Jahally Madina, Madina N’fally, Sare Babou, Sare Futa, and Sare Yewta—and Upper River Region (URR)—Basse, Kundam Mafatty, and Kundam Demba (see

Figure 2).

5. Results

The results of the study have been divided into four different sections, based on our initial objectives and the findings of the research done in The Gambia and in Spain.

5.1. Transnational Relations

In transnational relations, family and emotional ties are maintained throughout the migratory process and over time. In the current context, technological tools facilitate frequent contact between people who live at the place of origin and those who live abroad, in the same way that they facilitate the conservation of the role of the migrants in the family structure. On the other hand, the changes in methods of transportation, such as the dropping of prices in commercial flights, facilitate temporary return trips by the migrant families (

López-Sala and Godenau 2015).

As a collective strategy, migrations are considered as an investment which allows them to diversify the family’s source of income (

López-Sala and Godenau 2015). Participants who live in The Gambia explain that having relatives abroad is an advantage because they collaborate with the community (e.g., building healthcare centers, mosques, etc.) and provide extra income. Remittances are used to pay fees to the government and cover unforeseen expenses. In some villages, migrants organize themselves to contribute collaboratively to the entire village, such as helping the local economy and religious celebrations. At the family level, they contribute anytime someone needs health care or school fees as well as support in all types of celebrations.

“F: Yes, he is supporting us. If there is an accident, we will call him and he will send money to the family and he help us with the feeding of the family.”

Interview in Basse, The Gambia–Fanta, woman, Mandinka.

“Here, you must have relatives abroad to pay for the fees and feed for the family.”

Focus group in Kundam, The Gambia–Participant 1, man, Mandinka.

Any migration process also entails sacrifices and difficulties, to a different degree depending on the context (

Berry 1997). The separation of part of the family and the little time for reconnection were relevant aspects for Fanta and her husband Momodou. On the other hand, the prejudicious and stigmatizing attitudes in the West are described as one of the problems that the migrants have to face, present in the story of Saikou, who now is the Alkalo

1 of Jahally Madina and of Bintou.

“There are many pediatricians here talking about cutting without knowing what it is. […] This creates a lot of confusion and when they hear that this person is going to Africa and such and such, they immediately call the police, as has happened to me. Because that lady is going to Africa…, because it is a crime…, because they are going to mutilate her daughters…”

Interview in Sabadell, Spain–Bintou, woman, Serahule.

Continuity of the Culture

The continuity of the culture in the destination country is presented as a strategy to maintain identity and also family ties. In

Berry’s (

1997) terms, we could say that integration and separation strategies are positively valued, in which links with the country of origin are valued and preserved. The majority of those interviewed explain that their family members maintain cultural elements in the destination country, such as the traditional celebrations of “baptisms” and weddings. To preserve family ties, strategies are sought out to share the ceremonies with the family that lives in the country of origin, doing two ceremonies (one in the country of origin and one in the destination country) or recording and sending the videos to the family, if it is not possible to make a trip. On the other hand, migrants have an important role in the celebrations organized in the community of origin since, in many cases, they finance part of the ceremony.

“Even with the naming ceremonies they normally put it on tape and send it so we can see it.”

Focus group in Kundam, The Gambia–Participant 2, man, Mandinka.

“F: Momodou has the final decision now because he is the eldest and he has the final decision in this compound.

E: Which kind of things do you consult him?

F: Like marriages and naming ceremonies, we all get the final decision. Other… Including the family members. We already get the finance from him and inform him prior to his visit to… He will be there as the financer, yes.”

Interview in Basse, The Gambia–Fanta, woman, Mandinka.

In the migratory process and renegotiation of identity, the practices that should be maintained and those that should be abandoned must be selected. This classification is part of the adaptive strategy and, therefore, will vary depending on it. For example, it is possible that if the strategy chosen is segregation, all practices are considered positive, since there is no resignification of these. For most informants, integration is the strategy that operates, as they emphasize the importance of maintaining some of the cultural celebrations of the country of origin, while at the same time are opened to adaptation.

“Sometimes, if you are abroad and you live in a Western country, you will forget all our cultures. The Western people have their own culture but you will be here and live your culture, not leave your culture behind. Culture is part of you and there are good cultural practices and bad cultural practices. So FGM/C is part of the bad cultural practices: if our relatives that are abroad are not doing it, it is a good thing. But the other cultural practices like the ones that I mentioned (like naming ceremony) are a good part of the culture so anyone that forget that culture … it is a bad thing.”

Focus group in Jarumeh Koto, The Gambia–Participant 1, woman, Mandinka.

As we can see with the witness of this woman, the adaptive strategy of integration (

Berry 1997) is valued positively by the relatives in the country of origin but, at the same time, highlights the rejection towards assimilation, which implies the abandonment of the culture of the country of origin.

At the destination country, the way to maintain cultural identity is achieved through strategies such as the establishment of migrant associations of the same ethnic group, which function as an assistance and support network, strengthening the sense of belonging to the group of origin.

“O: We always have parties, we practice our culture so as not to lose the tradition ... There are very old traditions ... We must understand what is happening, the current situation, but we don’t want to lose our culture. […] With the association that we have, every month of the year, we pool money together into an account. If someone has a sick family member or has children or needs financial help for something … we can get some help from the association to help us pay for the flat, electricity, and food.”

Interview in Kombo, The Gambia–Ousman, man, Fula.

When asked about the practice of female genital mutilation specifically, the majority respond that it is no longer practiced and some say they do not know anything about the topic. The law and the migration process have changed the decision-making procedure.

“Before the coming of the law and the people being aware of the practice it was normal to take your grandchild. Even if she is from Europe, it was normal to do the practice. But now that there is a law and people are aware about the complications, no one dare to take the child from another person who is from Europe. That’s not happening here.”

Focus group in Kundam, The Gambia–Participant 3, woman, Mandinka.

5.2. Raising Awareness at the Origin and Destination

The awareness-raising works carried out in Spain and in The Gambia are aimed at transmitting knowledge to empower communities and promote conscious decision-making. In this sense, the results show that the training sessions pave the way for dialogue and encourage discussion about the practice within communities in the transnational space between the origin and destination.

The debate appears because not all people are convinced of the need to abandon the practice; some still defend its continuity. Even so, it is a progress that we can talk about a topic that until recently was taboo, as Momodou explains.

“K: Yes. When I come back from The Gambia last time, I talked with them [migrant friends] about all I had learned. I explained them my experience.

E: How did they react?

K: Some of them didn’t agree with me, they reject the topic. But they respect my opinion. I try to convince them. Although they may not think like me, we can talk about these things now.

E: Do you mean about female genital mutilation?

K: Yes, I was talking about that with them. Some of them weren’t interested in the topic.”

Interview in Cerdanyola, Spain–Momodou, man, Mandinka.

5.2.1. Activities in the Destination Country

The activities carried out in the destination country have an audience consisting mostly of migrant women with sons and daughters on the one hand and young people of first and second generations on the other hand.

During the awareness-raising and training sessions on FGM/C for migrant communities, topics arise such as the institutional violence they suffer from the system and difficult experiences are shared in which families have been criminalized and persecuted for planning or having carried out a trip to the country of origin. This is the case of Bintou and Fatoumata (another participant in the focus group), for example, whose passport was withdrawn due to the suspicion by the pediatrician of possible FGM/C to the daughters on a temporary return to the country of origin.

Despite the persecution they suffer due to being migrants and radicalized, they have an interest in the subject and the majority of women are proactive in reducing the practice of FGM/C in the country of origin.

“If society wants us to collaborate, we will do so, but they are rejecting us. [My activism against FGM/C] is being done of my own free will. I did so before what happened with my daughter. I want people to understand FGM/C in the same way as I have”.

Focus group in Sabadell, Spain–Fatoumata, woman, Mandinka.

The interviews also include a diversity of opinions, as in the case of one of the participants in the Sabadell workshops, who commented that they are not interested in talking about this topic because they have other concerns.

Young people and the associations also show interest and the will to be active in change. The majority of them are also convinced that the practice should be abandoned, and they say that the best way to achieve it is “doing training, talking about it and not neglecting it as an unimportant issue, is the only way you learn and you can change viewpoints”. (Barcelona, Spain, 2017—Focus group with young women).

“E: Are the associations interested in this topic?

O: Yes, yes. They really are. Because sometimes we have had meetings about this. In Sabadell, we have done all of this. And I know that the people in Europe don’t do this anymore. But before they did not know the consequences that it had because nobody explained it to them. Neither in Europe nor in Africa, the whole world was silent. This came about within about... eight or ten years now. But before, neither those in Europe nor those in Africa knew whether this was good or bad.”

Interview in Kombo, The Gambia–Ousman, man, Fula.

5.2.2. Activities in the Country of Origin

When migrant families travel back to The Gambia with their daughters, the parents explain to the grandmothers the consequences it would have for them to have FGM/C practiced on their daughters and that they would end up in prison. European laws change the role of every person in decision-making, opposing the characteristic gerontocracy of Gambian communities.

“I have a case that happened here, in Basse. The person came with the daughter and the grandmother wanted to circumcise the daughter. And the father said «no, you will not circumcise my daughter because if not, when I go back I will have problems in the place where I’m living». It happened in this village.”

Interview in Basse, The Gambia–Fanta, woman, Mandinka.

“My son’s daughter, meaning my granddaughter, was brought here but the father told me that any time I circumcise her, he will report me to the police. The father would have taken me to the police if I circumcise the daughter.”

Focus group in Jarumeh Koto, The Gambia–Participants 2, woman, Mandinka.

Migrants transfer the knowledge acquired at the destination country through training sessions, explaining to their families the risks and negative health effects involved in the practice. The protection in the law serves as a final and unquestionable argument, since the legal consequences that it can have for the parents (going to prison) would have detrimental effects for the whole family, but it is interesting because the debate also includes matters of health and well-being.

“E: Do people here hear the advice of people living abroad?

I: Yes, people hear the advice. Now, things are evident because the problem of this practice is too much. Women have major problems because of the practice. The woman or girl may die especially at the time of childbirth she may die. The problem is too much now they have realized that what the people abroad say about the danger of FGM/C is true.”

Interview in Jahally Madina, The Gambia–Participant 2, woman, Serahule.

From the point-of-view of migrants, the practice of FGM/C is related to educational issues and ignorance or naturalization of the healthcare problems involved. For this reason, raising awareness is key in preventing and abandoning the practice.

“Because this is something that is not from today, it is historic. The people who live in Europe have learned about the problem and know what it is. But before, people didn’t know. They did it and didn’t know what they were doing. […] In the end, as we are doing now, people are learning about the consequences that it has so that they stop doing it. But we must teach people about its bad consequences, you know?”

Interview in Kombo, The Gambia–Ousman, man, Fula.

5.3. Strategies for Prevention

The strategies used by the migrants to prevent FGM/C are varied. Ousman explains that there is an explicit willingness to work in a network to promote awareness.

“In Europe hardly anybody does this these days. Because they know the consequences that it has, right? But here still ... there are still people who do it ... But people are learning a lot. I myself was speaking yesterday with a lot of people who say that here, a lot of people do not do it now.

[The migrants] are learning a lot, a whole lot. Because nobody does it to their daughters and they live in villages, they explain it to people: to not touch them, to not do it... nobody touch my daughters ... The association we have in Europe is also focused on the topic. You know? We are not silent, any person who travels here always gathers together with the people of the villages and such, encouraging people not to do it.

Interview in Kombo, The Gambia–Ousman, man, Fula.

Promoting the abandonment of FGM/C with their own example is another one of the strategies used by migrants in raising awareness within their families that are influenced by some of the new practices from Europe.

Raising awareness in informal settings is told by Kumba, who explains her conversation with her husband’s family in The Gambia. The frustration appears when she has no more arguments to continue debating and raising awareness with her family members, due to the strength of the culture and the traditions.

“But when I was last in The Gambia I did speak about the topic with some women, but in the city. Because I saw, or rather, at my husband’s home there are ... There are little girls, so I was asking if they had done it. And one of them told me “yes, yes it has been done”. And I said, “But here in the city?” “You know that this is bad, right?” I was telling them that it is bad, that they can catch diseases, that they have birthing complications, with their period. Everything that this entails. […]

You get to the point that you are going to argue with them and you let it go because you say ...

Interview in Sabadell, Spain–Kumba, woman, Fula.

Finally, it is worth mentioning the use of preventive commitment as a prevention tool. This document was developed 20 years ago by Kaplan and began to be used with healthcare professionals in Catalonia, with the aim that the parents of the girls would use it during their trips to their countries of origin as a support element in their decision not to performed FGM/C on their daughters. This document intends to strengthen the commitment of fathers and mothers, after being sensitized by primary health professionals in Spain, avoiding the confrontation with the authority of the grandmothers and to relieve them of the pressures of the family environment in the countries of origin.

Although with the interviews carried out, only one family, Momodou’s family, claims to have seen the physical document, its use appears to be another element that can be useful for raising awareness, since other people recognize that they have heard about the document and that their family members have transmitted the information orally.

F: Momodou used the document to show me and also to his mother. Like this is better … if we circumcise our girl we will have problems in Spain.

E: Do you think that it is a good strategy, this document?

F: Yes, it is important and it is useful.”

Interview in Basse, The Gambia–Fanta, woman, Mandinka.

Momodou showed the document to his family, even though his daughter lives in The Gambia and, in this case, the document has no validity. This shows that it can be useful in situations that have not been considered until now.

In the case of Bintou, we have seen how she explains orally to her family the legal consequences of the practice. In this case, although the physical document is not explicitly used, we find the same preventive strategy.

“Yes, because we also tell them. If they do it, I’ll go to prison. And no mother wants their children to go to prison. That’s why.”

Interview in Sabadell, Spain–Bintou, woman, Serahule.

5.4. Education and Socialization of Boys and Girls

All of the people interviewed in The Gambia state that the girls do not suffer any type of discrimination due to not being cut when they return to the country of origin. In Kundam, we find a nuance in this explanation, since they recognize that before there was exclusion, but this is no longer the case due to increased awareness.

“E: Is there some social discrimination against the girls that are not circumcised?

I: Before, we used to do … call solima to discriminate. But it is no more operating, now it is normal … Because everyone is aware in the community so no one will be discriminated, so they don’t discriminate each other.

E: What about the people that come with their children from Europe and the girls, if they are not circumcised, are there any form of discrimination?

I: This is no more happening now, it is not happening in this community.”

Focus group in Kundam, The Gambia–Participant 3, woman, Mandinka.

However, the account of the communities differs from what the migrants say.

“E: Would your family or relatives tell your daughter something if she was not cut?

I: They may say it but in the absence of her. Why? Because they wouldn’t like to see her unhappy with her own family. They give them respect but they will say it, surely, they will continue saying it. Yeah.”

Interview in Cerdanyola, Spain–Momodou, man, Mandinka.

The young people who participated in the workshops in Sabadell (Barcelona, Spain) also talked about the subject and how they transferred information related to FGM/C:

“The information that we receive in connection to FGM/C is rather negative: ‘If they don’t do it to you, they are going to insult you (solima), they aren’t going to marry you, you will grow too much ...’ and these reasons cause some girls to want to undergo FGM/C.”

Focus group in Sabadell, Spain–Participant 3, woman.

The education and socialization of the children of migrants is interesting because it shows strategies for the transfer of cultural identity. In this aspect, the participants express their concerns and difficulties, caused by the intergenerational and intercultural clash that occurs between parents and children. Beyond FGM/C, a temporary stay by children when they are teenagers is proposed as a strategy for their acculturation in the parents’ home community. Other research has shown that “although some behavioral and cognitive elements of ethnic identity decline, immigrants retain a commitment to their culture.” (

Phinney 1990, p. 509).

“It is very hard and difficult to educate here, children don’t listen to use due to the dynamics that exist in the relationship between children and mothers, which is different in the West. That is why, when the children go to school, it is common to think about the option of sending them to Africa for a while.”

Focus group in Sabadell, Spain–Fatimata, woman.

“They don’t stay there forever, it is only for some time. So that they can pick up the culture from there, also ... for them to know that we have not come here just for fun, we came because we were suffering. For them to know what family is and when they have money, how to help, to meet the family. […] My daughter was there two years. Last year she returned. But my daughter is great. She doesn’t go out much and … […] Because my daughter’s age [19], who hasn’t taken her children to The Gambia, now everyone smokes and takes drugs and everything. But not my daughter.”

Interview in Sabadell, Spain–Bintou, woman, Serahule.

6. Discussion

The results show that the preservation of links with the community of origin, along with their own cultural identity, is one of the most relevant issues for migrants. Studies on the circularity of migration and the transnational space reaffirm this idea, giving meaning to research on the influence of migrants in their communities. (

López-Sala and Godenau 2015;

Skeldon 2012). In this case of integration acculturation (

Berry 1997), the ties of kinship and friendship are maintained, where a two-way relationship is established where obligations and care, decisions, and emotions circulate. In this transnational space, the conflict of loyalties occurs, but it is also where mutual influences can flow. New technologies in communication and transportation facilitate communication and the physical movement of people, cutting the symbolic distance.

Migration is presented as a survival strategy by certain members of the family to benefit the whole. Normally, migrants are young men of the group who send shipments to the family or organize in the destination countries to contribute to the economic policy of the community. In this sense, we talk about the conflict of loyalties to refer to the socio-cultural obligations to which migrants are subject with their families of origin and which may contradict the characteristics of the destination societies, creating shocks in the acculturation process.

In this context of changes and resignifications, the continuity of the practice of certain cultural elements is a key element in maintaining the cultural identity of migrants. The participants in the study explain that the decision-making in the family units of origin concerning the celebration of certain ceremonies is carried out jointly with the migrant members, who are often the sponsors of the events. The holiday calendar is jointly controlled and participation is coordinated, informing each other of the activities that will be carried out in each country. In that sense, some participants make a distinction between cultural practices that are considered “good”, where we would find traditional weddings and baptisms, and others that are considered “bad”, such as FGM/C.

As stated by

Johnsdotter (

2018), “there is evidence that migration leads to revaluation of the practices involving female genital cutting, resulting in growing opposition to these practices in concerned migrant groups.” According to the participants in the study, FGM/C is not still practiced in diaspora countries, although some comment that they do not know if some families travel to The Gambia with the intention of celebrating the traditional practice in the country of origin. Following tradition, it is the older women in the family who are in charge of organizing the ceremony; however, men are the leaders of the family and of the community in general and, with this role, they also have the power to decide and influence the circumcision of their daughters, being able to discuss the issue with their wife and mother, although not everybody does this.

The social and family structure is important to know how the decision-making process is carried out and how to channel influence that migrants can have on family members living in the country of origin. We have collected some cases that can be used as an example to see if there are controversies in families surrounding the practice of FGM/C. The events spoken about tell us about negotiations between grandmothers and migrant fathers and mothers who temporarily return with their daughters to the country of origin. The grandmothers, in this context, want their granddaughters to be cut and the parents get in the way of this decision, referring to the law in force in the destination country and to the consequences that the practice has on health. In this type of awareness-raising and family negotiations, the Preventive Commitment tool may be useful, created to provide more solid arguments that parents can use in family negotiations and avoid questioning the authority of their elders. It is offered to migrant families from countries where FGM/C is practiced as a voluntary resource before a temporary return trip to the country of origin and many of them accept and sign it.

What we can observe at this point is an important change in the dynamics of decision-making, which contradicts traditional gerontocracy, favoring the nuclear family and male decision-making power. Participants in the study stated that after raising awareness in The Gambia and knowing about the law, those who had the authority to make the decision were the parents, especially men, since legal responsibility lies with them. This may lead to the contradiction of empowering men on an issue that has so far empowered women, renouncing to the struggle for gender equality. It would be interesting to be able to go further in depth on the study of these changes in order to find out if there is an emergence of new strategies of social and grandmother’s pressures to counteract the empowerment of parents and promote the continuity of the practice of FGM/C. One of these possible strategies to avoid the current law in the countries of destination could be the fact that the girls, once cut, stay to live with the family in the country of origin and do not return with their parents.

On the other hand, the strong family pressure regarding continuity of the practice may lead to migrants financing the medicalization of FGM/C. Although we have not been able to collect systematic evidence on this reality, informal witnesses have explained their experience in this regard, opting for this option as a risk reduction strategy.

The main change indicated regarding the practice of FGM/C is age, since cutting is being done at younger ages than before. “Several studies indicate how FGC has changed, with the procedure being performed on younger girls and with less ritual fanfare than before, possibly because of increased parental fears of outside intervention. Other reasons mentioned for separating female circumcision from initiation rituals are socio-economic changes owing to urbanization and modernization.” (

Schultz and Lien 2013, p. 166).

The proclamation of the law encourages these changes, since when the girl is smaller, the cutting and its consequences are less visible and there are fewer risks of being reported and prosecuted. This decrease in the age of the girls implies a disconnect of FGM/C with the rite of passage of girls into adulthood which marks the entry of girls into the secret world of women, as pointed out by

Schultz and Lien (

2013). Without this transmission of traditional values, there is a generation gap and, as some informants express, girls lose respect for elders, a fact that calls into question the perpetuation of gerontocracy.

7. Conclusions

It can be asserted that the family and social structure of The Gambian communities is maintained with the migration of some members, who maintain their role in community decision-making, introducing the aspect of funders of certain celebrations or other events. We see changes in the traditional gerontocratic structure, since migrant fathers and mothers increase their decision-making power on the practice of FGM/C with their daughters, encouraging the authority of the nuclear family above other family members such as grandmothers or aunts. These changes are influenced by the existence and knowledge of the prohibitive laws in the destination countries, which they identify as directly responsible for the parents. The law proclaimed in The Gambia also encourages these changes, as well as the secrecy and advancement of the age at which FGM/C is practiced.

The awareness-raising tasks have a positive impact, both in the destination country and the country of origin. The study participants were aware of the health complications involved in the practice of FGM/C, as well as its legal consequences. All of them showed themselves to be in favor of the total abandonment of the practice, although they recognized that it is not an easy goal to achieve in the Gambian context, where it is deeply rooted in tradition and related to religious beliefs and aesthetic ideals and ideas of purity. The circularity used in the transfer of knowledge, in which it is a migrant person who organizes the awareness-raising sessions in their home community, is a satisfactory strategy, since it promotes a respectful approach to culture and promotes dialogue and debate, both in The Gambia and in Spain, as well as in the transnational space.

The main strategy used by migrants to avoid circumcision of their daughters is to refer to the law in the destination country and the consequences it would have for the whole family. Although this is the main argument, the damages of the practice for girls’ health are also explained, promoting knowledge in the communities. Community strategies have been included for the prevention of FGM/C in some villages of The Gambia, such as the application of economic penalties to those who continue to practice cutting.

Finally, in the study of the educational practices of migrant families we see how the intergenerational shock creates concern in mothers, especially when their sons and daughters reach adolescence. “It is possible that conflicts between demands of parents and peers are maximal at this period, or that the problems of life transitions between childhood and adulthood are compounded by cultural transitions.” (

Berry 1997, p. 21). At this time, the main strategy that is proposed is the temporary return for one or two years to the country of origin. With this trip, the teenager has the possibility of really getting to know the community of origin and the extended family, while socializing in a different environment and learning the cultural norms with which parents are governed, reducing the intercultural gap that it creates between the two generations.

It would be interesting to perform a more exhaustive study of this topic, to identify possible educational differences according to gender, while investigating the causes of the notable differences in the population of immigrant children from The Gambia, which are perhaps related to aspects of differentiated socialization.

In conclusion, we can assert that there is still a lot of work to be done and that dissemination is slow. However, the lines assessed in this study are heading in the right direction, promoting the empowerment of populations through knowledge and encouraging debate that promotes respectful change with the culture. This is the only way to achieve significant results.