Abstract

In recent decades, European rural development policies have transitioned toward a more place-based approach. This claim rests on the assumption that the diversity of resources within rural areas can be a potential source for place-shaping practices and sustainability. Moreover, this shift away from a top-down sectorial toward a more territorial focus has also shed light on the importance of agency, relations, and how people engage. Many rural areas in Europe, and particularly in Portugal, have seen a withdrawal of focus away from agriculture toward more diversified activities, where place-based approaches can untap local potential, stimulate sustainable place-shaping practices, and create significant well-being. However, some rural communities have difficulties in capitalizing on them due to unfavorable demographics such as depopulation and aging, a focus on traditional industries, and a lack of technical knowledge. The aim of the article is to discuss the role of place-based policies for enabling place-shaping practices revolving around traditional resources in rural areas and their contribution to sustainability. The study briefly highlights the recent debate around European rural development policies and illustrates their implementation through place-shaping practices via a case study in a Portuguese rural village—Várzea de Calde. The village revalorized itself and is trying to tackle marginalization processes through its traditional linen, which is a local material and immaterial resource, via collective agency and a strong sense of identity. The case study will provide empirical insights in discussing the effects of sustainable place-shaping practices stimulating by place-based policy instruments. Our conclusions highlight the positive contributions toward sustainability through improvements in social (e.g., identity) and economic well-being.

1. Introduction

This paper stems from the awareness that, in the last decade, rural development policies have profoundly entered into a new debate in science and policy arenas, moving beyond traditional, sectorial, and top-down approaches and moving toward a more place-based model (Barca et al. 2012; Bentley and Pugalis 2014; Celata and Coletti 2014; Hildreth and Bailey 2014; Horlings 2018; OECD 2014; Pugalis and Bentley 2014a; Pugalis and Gray 2016; Van der Ploeg et al. 2008). This model perceives place and rural development in relational terms and the processes of these relations as crucial for development. This “new paradigm” has come about to reduce the marginalization created by traditional approaches within regions and countries (Barca et al. 2012; Bristow 2010; Guinjoan et al. 2016; Tomaney 2010; and Varga 2017). Using an actor-centered perspective to look at the implementation of place-based policies, our main objective is to explore how place-based instruments are used by local actors to revalorize local resources in rural areas through sustainable place-shaping practices.

Place-based approaches take into account the diversity of local contexts, agency, and resources, which leads to tailor-made solutions for each place. These approaches have led us to rethink and reconfigure different policy solutions that can better promote sustainability in rural areas by tackling the underutilization of the local potential and decrease social exclusion (Barca 2009; European Commission 2015; Farole et al. 2015; Horlings and Kanemasu 2015; OECD 2009). Place-based approaches argue that all places have untapped potentials to grow and that policies should consider a place’s context and its diversity (Barca 2009; Varga 2017). Furthermore, to map resources and identify local potential, essentially that “place matters” (Pugalis and Bentley 2014b). Within it, institutions and policies can foster multi-level collaborative governance (Barca 2009; Celata and Coletti 2014; Pugalis and Bentley 2014a; Pugalis and Gray 2016). However, more research on place-based implementations in rural areas is still needed (Barca et al. 2012; Jauhiainen and Moilanen 2011; Neumark and Simpson 2014; and Pugalis and Bentley 2014b).

We argue that sustainable place-shaping practices have the potential to contribute to rural development and revalorize local assets and cultures when supported by place-based policies. Our goal is to discuss how place-based approaches can help the unfolding of these practices based on local resources, which contributes toward the sustainability of rural areas. We use the sustainable place-shaping framework developed by the European Marie Curie ITN research program SUSPLACE to study place-shaping practices. The SUSPLACE program (2015–2019) analyzes practices, pathways, and policies, which can support place-based approaches for sustainable development. For that, the program is built on the concept of sustainable place-shaping based on the assumption that, through collective agency and creation of networks, bottom-up initiatives can foster communities to shape places according to their needs, visions, and local resources. Sustainable place-shaping looks at the contribution toward sustainable development by re-localizing and re-embedding daily lived practices around social-ecological systems and place-based assets (Everett 2012; Horlings 2016; Horlings 2018; Roep et al. 2015). Sustainable place-shaping practices unfold along three main analytical dimensions considered to be key to a place-based approach for sustainable development (Horlings 2018): re-grounding, re-appreciation, and re-positioning. In our study of the linen case, we explore how unfolding sustainable place-shaping practices are effectively supported, or hindered, by policies. In addition, we take up Horlings’ call for a “need for place-based approaches and interdisciplinary solutions, which focus and build upon local resources, assets, capacities, and distinctiveness of places” (Horlings 2018, p. 304), and to what extent these policies can, even when intended to, actually be considered place-based.

Europe is a rich realm for exploring place-based policies, their implementation, and their effects on place-shaping practices. In order to overcome the discontents of previous space-blind policies, the European Union has been focusing on place-based policies and placing emphasis on developing the endogenous potential of rural areas as well as recognizing places with greater importance (European Commission 2015; Horlings and Marsden 2014; and Horlings 2018). For example, the EU Territorial Agenda 2020 and Cohesion policy argue that place-based approaches for rural development can better deliver the Europe 2020 strategy and best bring about sustainability over traditional sectorial and top-down approaches (European Commission 2015). In terms of rural implementation, and with its own limitations, the Community Led Local Development (CLLD, former LEADER1) approach has been providing a framework and channelling European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIF) for local empowerment, local strategy development, and resource allocation. We explore how these place-based policy approaches unfold in Várzea de, Calde, which is a village in central Portugal, and in effect, support sustainable place-shaping practices.

This paper is structured as follows. The next section reviews the literature to set the context of rural areas, development policies, and their impacts with a brief outline of the current state of debate on place-based policies. In Section 3, we elaborate on the concept of sustainable place-shaping and our framework. In Section 4, we present the methodology of our case study conducted in Várzea de Calde, which is a rural village in Portugal, and, in Section 5, we present our findings on how place-based policies actually stimulated sustainable place-shaping practices through the innovation of local traditional linen as well as how these practices untapped some of the local development potential. Section 6 discusses the interrelation between place-based policies and sustainable place-shaping practices. Section 7 leaves the reader with some conclusions.

2. European Rural Areas and Their Developments

2.1. Rural Areas in Europe: Transformations and Sustainability

Today’s rural areas are also the result of decades of well-documented transformations (e.g., Cloke 2006; Figueiredo 2008; Halfacree 2006; Jollivet 1997; Marsden 1995; Oliveira Baptista 2006; Shucksmith 2006; Soares da Silva et al. 2016; and Eusébio et al. 2017), mainly through top-down sectorial investments, usually in the agricultural sector. Such a focus mainly believes that, by improving agriculture, through economies of scale, specialization, and mechanization, the positive effects of a better competitive sector would spill over to the rest of the region, and improve communities and rural life. This strategy has partially worked, but only in certain regions and benefited only a few communities. A focus beyond agriculture and to wider activities of rural areas (e.g., tourism, crafts, and landscape) have taken an important role in European rural development strategies. The continued squeeze on agriculture has brought rural actors to engage in diverse activities, which, in many cases, have proved to be an effective response and adaptation (Van der Ploeg et al. 2000). Policies are an important tool for transformation and allow governments to shift certain practices and behaviors deemed unfavorable for society and the environment, or to support new innovative sustainable practices for development.

The decrease in the centrality of agriculture in many rural areas is a major trend in many European countries, particularly in more peripheral or remote regions (Cloke 2006; Figueiredo 2008; Figueiredo and Raschi 2012; Halfacree 2006; Jollivet 1997; Oliveira Baptista 2006; and Shucksmith 2006). Furthermore, these regions have seen socio-economic decline and restructuring from densely populated space and predominantly agricultural-based activities (rural as a place of production) to sparsely populated and diversified consumption-oriented activities (rural as a place of consumption) (Almstedt et al. 2014; Burton and Wilson 2006; Halfacree 2006; Silva and Figueiredo 2013; Soares da Silva et al. 2016; Van der Ploeg et al. 2008; Wilson and Burton 2015; and Woods 2007). This transformation from a predominant agricultural space to a more diversified space has been highlighted by the OECD policy orientations of a “New Rural Paradigm” and through academic discourses on “post-productivism” (Almstedt et al. 2014; Evans et al. 2001; Marsden 1995; Oliveira Baptista 2006; and Wilson 2001). This transformation can be understood as a shift from the previously dominant food production goals toward a more complex, contested variable mix of production, consumption, and protection goals (Eusébio et al. 2017; Figueiredo 2008; Holmes 2006; and Soares da Silva et al. 2016).

Diversification, multiple activities, and their symbiosis have been transforming rural areas, and, in some cases, led to revaluation of endogenous resources through sustainable place-shaping practices. Traditional activities, such as a production of local foods and crafts, can further be exploited through innovative links and processes with new and/or other existing activities in the community (ECVC 2015; Gobattoni et al. 2015; and Pato et al. 2015), such as tourist accommodation and gastronomic routes. This shift toward a wide diversity of activities within a regional level can be supported by place-based policies, and can lead to new relations with producers, markets, and tourists, which can favor the preservation of traditional and landscape-linked activities that hold intrinsic social value (Gobattoni et al. 2015). These transformations have the potential to improve the sustainability in rural areas, by maintaining social practices, improving economic opportunities, and reversing negative population trends.

2.2. Rural Development Approaches and Policies

Policies for rural development aim to improve and reverse the many negative trends, difficulties, and disadvantages that rural areas (especially peripheral) are facing in striving for general well-being. Traditional space-blind policies have encouraged, in many cases, a development without consideration for the local context (Barca et al. 2012; Bentley and Pugalis 2014; Bristow 2010; Gill 2010; and Pugalis and Gray 2016). These approaches believe in the concentration of resources in an economic core (city or leading sector) and encourage mobility through infrastructure as the best approaches leading to even geographical distribution of wealth by taking advantage of agglomeration effects of growth (Atterton 2017; Barca et al. 2012; Castells-Quintana and Royuela 2018; Olfert et al. 2014; Varga 2017; World Bank 2009). However, their success has been limited, and its “one size fits all” approach has further led to polarization of development between places (Barca et al. 2012; Bristow and Healy 2014; and Varga 2017).

In contrast, place-based approaches do not solely focus on a core (city or sector) but on the potential for development and growth in every territory (Barca et al. 2012). Recent EU policy seems to be increasingly focusing on developing endogenous potential of rural areas through its Europe 2020 strategy (Horlings 2018; Horlings and Kanemasu 2015), Cohesion policy, and the Territorial agenda 2020, which explicitly calls for the adoption of place-based approaches through mechanisms such as LEADER\CLLD (European Commission 2015). Place-based approaches appreciate and valorise diverse local contexts and resources beyond economic wealth, such as social (e.g., local traditions and values), environmental (e.g., natural landscape, resources), and economic (e.g., local products). Local communities and institutions can shape their territories to their needs through sustainable place-shaping practices of re-positioning, re-grounding, and re-appreciation. These practices are key toward a place-based strategy for sustainable development that considers the particular heterogeneity and diversity of places, in terms of social, cultural, and institutional characteristics (Horlings 2018) and attempt to tackle the underutilization of local potential in order to decrease social exclusion (Barca 2009; Horlings 2015a; and Horlings 2018). It does so by integrating a place’s specificities in the forms of social, cultural, and institutional characteristics and valorizing the potential of local knowledge, needs, values, and networks (Horlings 2015b). A place-based approach then should be considered to increase self-efficacy through bottom-up development and decentralization of decision-making (Roep et al. 2015). Still, more research is needed to understand how to best implement a place-based approach (Jauhiainen and Moilanen 2011; and Neumark and Simpson 2014), especially in non-metropolitan regions (Pugalis and Bentley 2014b).

The increased diversification in rural areas can lead communities to valorize and innovate endogenous resources through local values, culture, and agency. Sustainable place-shaping is a notion that favors bottom-up initiatives toward rural development and well-being. It is important for communities to shape their place to their needs and in accordance with their diversity, resources, and visions. Collective agency is based on the creation of new collaborations and relations between diverse stakeholders. By agency, this means the ability to build human capacity to reassemble and transform relations for their benefit (Horlings et al. 2018). Putting place and agency at the center of rural development approaches can allow for a better understanding of power relations and how practices unfold.

Yet place-based policies also come with their own critiques, challenges, and limitations (Bentley and Pugalis 2014; Celata and Coletti 2014; European Commission 2015; Mendez 2011; and Pugalis and Bentley 2014b). Most importantly, there is no single model for place-based strategies, as they should stem from the analysis of local assets and capabilities (Bentley and Pugalis 2014; European Commission 2015; Pugalis and Gray 2016), which can lead to “neo-liberal” appropriation and policy capture toward one dominating mode (Celata and Coletti 2014; Pugalis and Gray 2016) and a withdrawal of state responsibilities for public engagement (Bock 2018). Furthermore, the greater the differentiation of place-based policies, the more challenging it will be to make consistent regional policy (OECD 2009). Other limitations of place-based policies can be summarized as risks of territorial introversion, strategic fragmentation, and institutional isomorphism (Celata and Coletti 2014; and Pugalis and Bentley 2014a). In addition, the implementation of policies is challenged by the involvement of many actors (horizontally and vertically) and the trust it requires (Atterton 2017; and European Commission 2015). EU strategic documents call for place-based approaches, but are often disregarded when planning and implementing them on the ground (European Commission 2015). “In summary, what have we learned from the available evidence? The answer is probably—not enough.” To guide policy, we need to know more about what works, why it works, and crucially for place-based policy, where it works, and for whom it works” (Neumark and Simpson 2014, p. 73). We notice that there is still research needed in order to further understand how to account for its limitations and impacts.

Nevertheless, space-blind and place-based policies should not be seen in a false dichotomy but as working together (Farole et al. 2015; and Varga 2017). Proponents of space-blind policies leave place-based interventions open in parallel with space-blind, but only “if history, language, or culture prevents people in lagging regions from accessing the economic opportunities in leading places, place-based economic incentives can help” (Gill 2010). Furthermore, place-based policies welcome spatially uniform strategies and regulations to institutions and provision of essential public services and concord with some of the potential values of agglomeration economies (Garcilazo et al. 2010). As Garcilazo et al. (2010, p. 17) state “many forms of regulation need to be economy-wide in order to avoid creating potentially large distortions (…) even if some dimensions of implementation may involve differentiation across space” and pose diverse challenges that suggest that spatially blind policies are not neutral in terms of impact. Additionally, in some cases, places do not hold untapped potential, and top-down agglomeration interventions might be a more effective solution (Barca 2009; and Varga 2017).

2.3. Uneven Developments in Portugal

Portugal has been through major transformations due to de-ruralization processes of the country, top-down support for city agglomeration, agricultural modernization, and growth as the sole engines for regional development and a further neglect for the provision of essential services to rural areas (Figueiredo 2013; and Figueiredo et al. 2014). Decades of these type of policies have further created marginalization divides within regions (coastal versus interior and north versus south) and contributed to depopulation of rural areas (Dos-Santos et al. 2014).

Moreover, Portugal is an example of the legacy impacts that space-blind policies had by not taking into account differences in rural areas, among others, in terms of geography, demography, and culture. Space-blind support for the size maximization of farms and modernization of agriculture resulted in uneven developments within the country, which leads to marginalization of certain areas, especially a stark contrast between the mountainous north and the flat landscaped south, where agricultural maximization was more conceivable. Furthermore, agriculture has lost its main role as the sole provider for rural areas. This can be seen particularly in central and northern regions where decades of traditional and space-blind policies have left small farms marginalized (Marta-Costa and Silva 2015; and Silva and Figueiredo 2013). Furthermore, investments, infrastructure, and agglomeration policies aimed at cities further led to a demographic shift out of rural areas, which leads to depopulation and aging. This led to many rural areas being extremely marginalized and in dire need of attention, alternative incomes, and a new “raison d’être” (Oliveira Baptista 2006; and Figueiredo 2008, 2013).

Diversification of activities in rural areas have become an accepted adaptation response for small-scale farmers (Everett 2012; Figueiredo and Raschi 2013; Marta-Costa and Silva 2015; and Van der Ploeg et al. 2008), which makes them focus on local resources they may utilize. Tourism, landscape conservation, energy production, and traditional products as well as new practices embedded in local resources and knowledge have become distinctive resources that each locality could strengthen (ECVC 2015; Figueiredo 2013; and Pato et al. 2015).

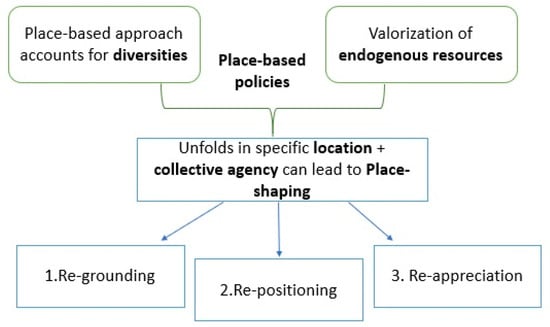

3. Rural Development through Sustainable Place-Shaping Practices

Sustainable place-shaping is a concept that tries to analyze the contribution toward sustainable development from practices which re-localize and re-embed daily lived practices around social-ecological systems and place-based assets (Everett 2012; and Horlings 2016). Hence, transforming the relations between people and their environment and differentiating structuring processes, which ‘propel’ everyday living, sociocultural (re-appreciation practices), political-economic (re-positioning practices), and ecological processes (re-grounding practices) (Horlings 2016; and Roep et al. 2015). “These unbound processes provide the space for people to position themselves and perform agency via those place-shaping practices. Processes of sustainable place-shaping ‘connect people to place’” (Horlings 2018, p. 6). Place-shaping concentrates on how to build capacities of people to reflect on and to renegotiate the conditions for their engagement in places. We can argue that people have agency in the shaping of a place, which leads to the place being social. People are also spatial beings. Therefore, “an explicit recognition that place matters is also an implicit recognition that people matter” (Pugalis and Bentley 2014b, p. 571). Place-shaping further sees place as a ’meeting point’ for ecologies, economies, and communities (Horlings 2016). It uses a relational approach to place and define it as established in social practices, relations, and interactions emphasizing a sense of identity and belonging of rural communities. It assumes that the nature of a place lies not only in its internal features, but as a result of its connectivity with other places. Thus, places are an outcome of networks and intersections that integrate global and local areas (Massey 2005). “Sustainable Place-shaping stems from the definition of place from a relational conceptualization as seen as the outcome of constant flows and networks and as a dynamic outcome of a multiplicity of relations” (Horlings 2018, p. 7). By understanding these relations and the contexts in which they unfold, place-shaping is a useful concept for studying rural communities and their practices as it explores the transformative agency and engagement of people in relation to economic and cultural global processes in order to try and to shape a place according to their values and needs (Horlings 2016). Within place-shaping, some of its fundamental aspects revolve around fostering the active and innovative use of local agency and resources as well as involving all stakeholders and actors in creating relations and networks (Domínguez García et al. 2013; Horlings 2015a, 2018). Therefore, the importance of place and its inherent specificities is a central aspect of both place-based policies and sustainable place-shaping practices. In our research, we use both concepts and argue that the former can stimulate the latter. Figure 1 captures our framework of analysis for the case study research.

Figure 1.

Unfolding of place-based approaches: an analytical framework.

Although the valorization of endogenous resources is part of the place-based approach, together with place-based policies, strategies, and instruments, for analytical purposes, Figure 1 portrays these dimensions separately. Figure 1 contends that place-based approaches account for the diversities of rural areas and can lead to valorization of endogenous resources (European Commission 2015; Horlings and Marsden 2014; and Horlings 2018). This process unfolds in a specific location where, together with collective agency, can lead to various place-shaping practices. These practices are embedded in local knowledge and resources (Domínguez García et al. 2013; and Horlings 2015a, 2018) and place-based policy instruments can support untapping local potential for rural development through diversities (Barca 2009; and Barca et al. 2012). Our case study Várzea de Calde exemplifies this by showing how place-based policy instruments allow for greater focus on the potential of local resources, both in terms of knowledge and material.

4. Materials and Methods

The Case Study—A Portuguese Rural Village, Várzea de Calde

Within the above-mentioned context, Várzea de Calde was chosen since it embodies most of the characteristics of a rural village in the Central region in Portugal. Furthermore, it was chosen for its peculiar identity linked to linen traditions, which is used to stimulate all three place-shaping practices based on local resources and supported by place-based instruments. These practices, such as hand-spinning linen, can have important roles in potentially restructuring Várzea’s local economy, improving social cohesion, maintaining traditions otherwise lost, and reinforcing their sense of belonging and identity (Vasta and Figueiredo 2018).

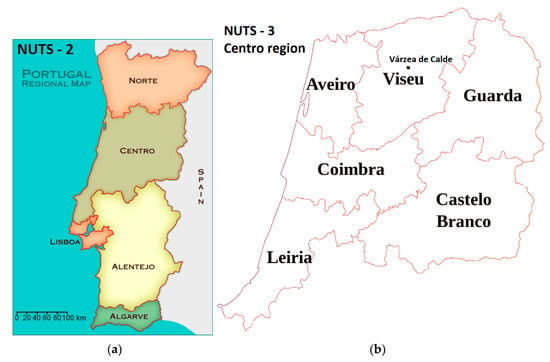

Várzea is a small village of about 220 inhabitants (2017, own data collection) in the parish of Calde (1469 inhabitants in 2011, (INE 2016), which extends in an area of about 30 km2. The maps in Figure 2 show the location of Várzea de Calde (right), in the Viseu municipality within the district of Viseu (NUT 3), in the Center region (NUT 2) of Portugal (left). The parish resembles many of the socio-economic problems that previous policies have exacerbated in the region as it is characterized by a declining population, with peak decline from the decade 1981–1991, and a milder display in the consequent decades (Bidarra 2013; Daliakopoulos and Tsanis 2014; and INE 2016) due to emigration to cities or abroad. Furthermore, it has an elevated proportion of the elderly population and a considerable level of illiteracy (over 10% in 2011) (Bidarra 2013; Daliakopoulos and Tsanis 2014; INE 2016). Previous policies focused on agglomeration of resources in cities and lack of support for rural areas have furthered aggravated the negative trends. They have affected the decrease of economic activities in the parish, which led to a decline of 66% in agricultural output and an unemployment rate of 13.6% in 2011 (Bidarra 2013; INE 2016).

Figure 2.

Regional map of Portugal NUTS 2 (a) (Alport 2019), Central region, and its districts NUTS 3 (b) (Own creation).

In terms of rural development, Várzea is a recipient of various funds. National funds through the Direção-Geral de Agricultura e Desenvolvimento Rural (Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development) have the aim to support agriculture, diversification of activities, and creation of rural jobs and reverse depopulation (DG ADR 2018). The national rural development program (PDR2020), part of Portugal 2020 strategy, is implemented in the region through the CENTRO 2020 program that receives European Rural Development Fund (ERDF) and European Social Fund (ESF) funds as well as CAP’s second pillar rural development policy fund known as European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD). A percentage of these three main European funds for rural development (ERDF, EAFRD, ESF) are channelled in Várzea through the bottom-up (place-based) approach of LEADER\CLLD. The Local Action Group (LAG), ADDLAP—Associação para o Desenvolvimento Dão, Lafões e Alto Paiva—was established in 1994 through the LEADER II experience and aims to provide assistance and access to fund local projects and strategies. ADDLAP had a paramount role in supporting—together with the local Parish, through LEADER channels, and FEDER funds to buy equipment—the formation of the Cooperativa do Linho de Várzea de Calde (Linen Cooperative) on 2 April 2006.

A case study method has been chosen because of its focus to gain insights on complex real-life activities and impacts and its ability to understand some particular problem or situation in depth (Kahirul 2008). Most of the field case study was conducted from June to September 2017 with some interviews throughout 2018. A qualitative approach has been used with participatory field work and semi-structured interviews, which included 15 cooperative members, seven community members, three local institutions (municipality and parish), one Local Action Group, one NGO, one designer, one trainer, and the museum. More than half of the cooperative members interviewed are 65+ years, and four are below the age of 50. Within the community members, two interviewees are below 35 years of age. The stakeholders were chosen through a snowball technique, which started with the NGO Binaural-Nodar, partners in our SUSPLACE project. They have been working in the area beforehand and introduced the researcher to the museum manager, to employees, and to some local community members, which allowed the researchers to gain trust and further access to more stakeholders. Semi-structured interviews were used to deduce how the village was able to maintain the linen tradition through sustainable place-shaping practices and place-based policy instruments. The interview protocol covered three main themes: links and values related to linen, the history, policies, and their role in the development of linen, and the challenges and opportunities for the future. A qualitative method of thematic analysis (Alhojailan 2012; and Braun and Clarke 2006) has been used based on the interviewees’ relations to place-shaping practices and policies that stimulated valorization of local resources. Our analysis comprised a qualitative coding of interview transcripts. The coding started with categorizing the key place-based policies that had supported the linen of Várzea. Then, we coded the key events that changed the practices around linen in Várzea and categorize them by the three place-shaping practices. Specifically, as outcomes of interest, we explored how actors used policy instruments for sustainable place-shaping practices to revalorize resources.

5. Results

Events, Key Place-Based Policies, and Place-Shaping in Várzea de Calde

The fieldwork sheds light on relevant policies and events that developed around linen in Várzea, which are summarized in Figure 3. We can see momentum quickly picking up after the museum’s entry into the community in 2009 and an increase of supporting place-based policies. Many of the collaborations and new networks for linen have been revolving around the museum, which takes a dynamic and leader role in the development of sustainable place-shaping practices. Within the aim of facilitating rural development, ADDLAP and the Viseu municipality have acted as catalyzers for Várzea’s development around linen.

Figure 3.

Timeline of developments around linen in Várzea.

Through a timeline dimension, Figure 3 highlights the main developments around linen and the policies that supported them. Várzea is widely recognized in the region for its link with linen. Due to its fertile land, in the vicinity of the Vouga river, its strong bonding social practices made linen a very important resource for both usage and commerce throughout Várzea’s developments. This led to a deeply rooted tradition and a fame for its highly dedicated “spinning and weaving” women, who are highly motivated by a generational and family legacy of linen practices, as the following quote confirms.

“My family has always been connected with weaving. My great grandmother used to weave, and so did my aunts. My mother also weaves”.(Cooperative 15)

Linen has many usages such as for fiber, seeds to plant the next year, for food, or for medicinal use. The timeline also tries to show the linkages of place-based instruments with the unfolding of sustainable place-shaping practices in Várzea. The linen tradition started to take a more “organized” turn in 1963, when the Grupo Etnográfico de Trajes e Cantares do Linho de Várzea de Calde (commonly referred to as the singing group) was established with the partnership of the local parish, and still performs today. The group collected and performs songs related to each step of the linen cycle that were “handed down” by their ancestors. This was the first officially recognized group related to linen in Várzea and is based on voluntary work and is self-managed.

During the 1980s, linen in Várzea saw a dramatic decline, due to emigration, to the point that, by the early 1990s, very few people planted flax. This took an important turn when some local leaders encouraged a training given by Estação Agraria de Viseu and sponsored by DG-ADR and CEARTE (Centro de Formação professional para o Artesanato e Patrimonio) in 1999. CEARTE is a center that conducts trainings and professional education related to arts and crafts based on endogenous resources in order to improve job creation. It is funded through National funds and ESF—European Social Fund. This training taught younger women the traditional skills and processes around linen. Some of the attendees further continued other courses with CEARTE to improve and learn more. The majority of interviewees regard the training as crucial for the tradition’s survival.

“There was a time when linen was not planted anymore …. but then after, the training people started to regain confidence”.(Cooperative 7)

“If it weren’t for the course we took, linen in the village wouldn’t have been the same because many of us had not enough knowledge about it—didn’t know how to do the whole process”.(Cooperative 5)

This is an example of sustainable place-shaping through re-grounding practices, as these are embedded in local resources and knowledge and have been passed onward.

This dynamism peaked in conjunction with further support toward more place-based approaches, programs, and funding both at the EU (LEADER programme) and National level (Vasta and Figueiredo 2018). As already mentioned, in 2006, 20 women formed the Cooperativa do linho de Várzea de Calde. This was supported by the local Parish and ADDLAP, which established a second official group around linen. The local parish has been fundamental for stimulating and supporting the creation of the cooperative and ADDLAP crucial for providing access to funding. Most of the people of the cooperative believe that it maintains the traditional linen practices, by emphasizing the re-grounding practices, but also hopes for potential income and young people to stay in Várzea. This is a re-positioning practice.

“We created the cooperative to have this economic effect … to raise interest in the young ones”.(Cooperative 2)

Furthermore, many people see the cooperative from a re-appreciation practice:

“I joined the cooperative because I wanted to learn, to learn the traditions of our village”.(Cooperative 3)

“The cooperative was created not long ago, to see if this tradition wouldn’t die”.(Community 6)

Consequentially, the idea of creating a museum spurred thanks to the local Parish and some community members working together. These actors collaborated to submit a project to renovate and convert an old house to a museum and received funding through the cooperation of ADDLAP, CCDRC (Comissão de Coordenação e Desenvolvimento Regional do Centro), and Viseu municipality. This initiative received policy support from regional funds and was co-financed through national and FEADER funds. Lastly, the museum was inaugurated in 2009 and has been working closely with the cooperative by ultimately serving as a crucial dynamic actor for all three sustainable place-shaping practices.

Re-grounding: Through a dedicated “pedagogical” space, the Museum allows the cooperative to get together and work and show their practices.

“With the museum, a dedicated space for the cooperative to showcase and sell their products, but also a space to work together with a loom for those that don’t have one”.(Cooperative 1)

Re-appreciation: The museum showcases the local heritage and traditions of linen.

“The museum conserves the immaterial heritage of Viseu”.(Institution 2)

“It is very satisfying to see many visitors that come and appreciate our tradition”.(Community 7)

Re-positioning: The museum is a major linkage for finding new markets\partners. It has a dedicated selling space for linen products.

“… now with this space (museum), they finally have a feedback from consumers about the quality and marketability of their products”.(Trainer)

“The fact of the museum being here has taken Várzea’s linen to another level. Before we had to go look for clients, now they come to us!”.(Cooperative 3)

The museum is seen by all the interviewees as a positive addition to the village.

“The museum is very dynamic …. its creation accelerated the creation of what we see today”.(Institution 3)

In 2015, the museum and Viseu municipality started a collaboration with the NGO Binaural-Nodar with the intent of collecting ethnographic data on Várzea and its linen tradition. The NGO has many years of experience in rural areas, heritage, arts, and ethnography, which led to many important outputs such as a video-documentary on the traditional linen cycle and many artistic exhibitions. These were possible thanks to funds through the EU Creative Europe program, the National culture funds DG-ARTES (Direção-Geral das artes), and Viseu-Rural, which are strategies for rural valorisation. Binaural’s collaboration brought about important re-appreciation practices that most of the interviewees acknowledged.

“Binaural’s contribution is fantastic, we can update our data collection, do new expositions … they are doing an ethnographic work on linen here never done before!”.(Institution 1)

A new partnership also spurred in 2017, following the sale of the cooperative linen, through the museum, to a Portuguese designer for her artistic creation. This has allowed the cooperative to make a positive economic balance and a partnership. The designer created and trademarked a brand for the cooperative, by developing new products and reaching new markets. These projects have received funding through ADDLAP from ERDF funds. This collaboration is still early on, but most of the cooperative members are enthusiastic and can be seen as supporting clear re-positioning practices.

“The new handcrafted work, together with our linen can be valorized by customers”.(Cooperative 6)

With these partnerships and the support of the Viseu municipality, the future strategy for Várzea´s linen is to market itself nationally and internationally, by applying UNESCO´s intangible heritage spearheaded by the municipality. Moreover, other projects such as the “linen school” attract and share Várzea’s identity and tradition with the younger generation.

Traditional linen in Várzea is being revalorized in diverse ways that are related to the three place-shaping practices, which are summarized in Table 1 below. The table highlights the most important events that stimulated new synergies, networks, and opportunities.

Table 1.

Summary of sustainable place-shaping practices in Várzea.

6. Discussion

With our field research in Várzea, we tried to gain insights if place-based policies have the potential to spur sustainable place-shaping practices and revalorize endogenous resources through collective agency. The case study suggests, as already explored by Horlings (2018), a link between the increasing place-shaping practices and the growing orientation of policies toward place-based approaches. Practices unfolding in Várzea seemed to have increased with the availability of place-based instruments.

In the case of the linen cooperative, place-based approaches with a focus on local resources, culture, and craftmanship, have allowed the community to organize a training on a traditional linen cycle and, consequently, access EU funds, thanks to LEADER\CLLD approach, to acquire machinery and constitute the cooperative. Through the interviews, it showed that these instruments have played a key role in establishing a positive outlook, gain momentum for the other events, and spur collective agency by different stakeholders working together toward a common goal. In addition, it is interesting to note that the initial developments focused on re-grounding and re-appreciation practices, which served to establish an “inner” connection with local identity and traditions within the community and then followed a more “exterior” look toward re-positioning to new markets and products. This can be seen as a possible learning lesson for other similar regions to uptake sustainable place-shaping practices in a comparable way. In line with authors on place-based policies (Barca et al. 2012; Bentley and Pugalis 2014; European Commission 2015; Mendez 2011; and Tomaney 2010) that state that multi-level governance is important for implementation, the empirical case showed this type of arrangement was, in fact, created through strong networks between local parish, museum, community, Viseu municipality, and ADDLAP. Furthermore, the authors also call the identification and mobilization of local resource and knowledge as one of the main dimensions for a place-based strategy. Through its established centenary linen tradition in Várzea, this has been rather straightforward. Moreover, the collective agency has turned out to be crucial. Varzea’s community shows that a deep sense of belonging, tradition, and identity can spur agency and stimulate place-shaping practices. The process and the strategies implemented and followed in Várzea de Calde may be replicable to other marginalized rural areas with similar characteristics. However, as mentioned, place-base policies are about the specificities of the places and are anchored in their resources, social values, and practices.

Without place-based policy instruments, many of these practices would not have occurred. However, policies do not create impacts, as collective agency and trusted networks are shown to be essential for implementation and in seizing opportunities. Place-shaping practices and place-based policies in Várzea partly contributed to sustainability in rural development by going beyond economic dimensions and enhancing social aspects such as local identity and traditions. Nevertheless, place-shaping practices in Várzea remain limited in their scope since only some community members are economically benefiting from them and the future is still at peril due to depopulation trends. However, some young people in the community do not feel that linen is as important for their future.

“Linen is not profitable, it’s not an alternative for the young ones to stay here”.(Community 6)

Despite some success, these practices may not have continuity if young people do not see economic returns. Moreover, with little infrastructure, an aging population, and local young people not finding conducive conditions to stay, there is a risk that these place-shaping practices will lose ground. As much as policies might be place-based, if local people are not engaged, or do not have the ability or skills to engage, development will hardly improve. Thus, place-based approaches are helpful, but not an ever-encompassing silver bullet for rural development. It is possible that other interventions are needed in order to meet the other challenges that Várzea is facing.

As mentioned earlier, all places do not necessarily hold untapped potential, and top down agglomeration interventions might, sometimes in parallel, be a more effective solution in those cases (Barca 2009; and Varga 2017). What about places that do not have endogenous resources? What about others that do not have any agency, because of extreme depopulation? These are realities where place-shaping and place-based approaches may not be as successful as in Várzea, and a mix of strategies with space-blind approaches may provide the best benefits.

7. Conclusions

Place-based approaches have been increasing their relevance in European rural development discourses. Within this context, the article has argued that place-based policies are crucial for stimulating place-shaping practices and contribute toward sustainability and rural development. In our case study, these policies stimulated a marginalized rural area to valorize its local resources (material and immaterial) and build a collective agency. Just as many rural regions in Europe, our case study village Várzea de Calde has gone through transformations via globalization processes and effects of previous space-blind policies. These led to restructuring of economic activities away from agriculture, lack of infrastructure, negative demographic trends, and loss of traditions and practices. However, opportunities for diversification of activities have also been present and, through place-based policies, have spurred sustainable place-shaping practices.

Our case study, although limited in scope, reveals how sustainable place-shaping practices have unfolded in Várzea de Calde with the support of place-based policy instruments. Through its three practices, known as sociocultural (re-appreciation), political-economic (re-positioning) and ecological processes (re-grounding), sustainable place-shaping has proven well equipped to contribute toward sustainability by allowing these dimensions to be fostered. The community has benefited both in social and economic terms from these practices as dynamism and partnerships around linen grow.

Moreover, a place-based approach contributed by stimulating these practices through policies and instruments that let local resources to be the source of development. Through its inherent appreciation of place and its relational aspect, it allows for a deeper understanding of local needs, values, and relations. Place-based policies and the institutional levels of governance created to assist and fund local projects have developed opportunities for the rural community to adapt their development strategy to their needs and specificities. Likewise, Várzea shows us how place-based approaches have proven to untap local potential by recognizing the endogenous resources as fundamental aspects. Through the LEADER\CLLD framework, it allowed for local diversities to become opportunities for social and economic well-being by funding local projects and opening possibilities. Furthermore, the framework facilitated collaboration between stakeholders. However, policies can help support communities socially and economically, and foster place-shaping practices, but these policies are not the ultimate reasons why communities are successful or not. Their collectively built agency was crucial, as it created new relations and collaborations between different stakeholders from different domains. By their very nature, place-based policies are implemented in places with different characteristics, and it is not just the policy details that vary but the economic and social environments in which they are set (Neumark and Simpson 2014). As the case study suggests, the agency, a multi-level governance system, and a network of actors bonded by shared trust, are essential factors for policy implementation to successfully assist sustainable place-shaping practices. Moreover, demographical and educational background are also impediments for agency and implementation of some policies, as many involve bureaucratic, complicated language and requirements and become difficult to access. Thus, an institutional body, such as ADDLAP in Várzea’s case, can filter and make the policies initiative more accessible to rural communities. However, place-based policies should still be seen in the light of a multi-policy strategy complemented with other policies (space-blind), which strengthen local institutions, infrastructures, and the provision of basic public services.

The discussion of the specificities of the case study presented in this paper would benefit from a comparison with similar contexts and processes. However, the lack of similar studies and data hinders such a comparison unveiling, and, at the same time, hinders the need for further research, particularly within the European context.

Author Contributions

A.V. is responsible for the writing, data collection, and analysis. The other authors have contributed to the article by reading, commenting, and giving feedback and propose literature on the various drafts.

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 674962.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Alhojailan, Mohammed Ibrahim. 2012. Thematic analysis: A critical review of its process and evaluation. West East Journal of Social Sciences 1: 39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Almstedt, Asa, Brouder Patrick, Karlsson Svante, and Lundmark Linda. 2014. Beyond Post-Productivism: From Rural Policy Discourse to Rural Diversity. European Countryside 6: 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alport David. 2019. Portugal Regional Map. Available online: https://uprightandstowed.typepad.com/.a/6a00d8341cab4853ef012876ba6703970c-popup (accessed on 12 May 2019).

- Atterton, Jane. 2017. Place Based Policy Approaches and Rural Scotland, RESAS Strategic Research Programme Research Deliverable 3.4.2 Place-Based Policy and Its Implications for Policy and Service Delivery (July). Edinburgh: RESAS, pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Barca, Fabrizio. 2009. An Agenda for a Reformed Cohesion Policy. A Place-Based Approach to Meeting European Union Challenges and Expectations. Innovation, (April), 8826681. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/archive/policy/future/barca_en.htm (accessed on 2 July 2017).

- Barca, Fabrizio, Philip McCann, and Andrés Rodríguez-Pose. 2012. The case for regional development intervention: Place-based versus place-neutral approaches. Journal of Regional Science 52: 134–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, Gill, and Lee Pugalis. 2014. Local Economy Shifting paradigms. Local Economy 29: 283–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidarra, Simões João. 2013. A Gestão Florestal e a Gestão Pós-Fogo—Visão dos Proprietários. Master’s thesis, Universidade de Aveiro, Departamento de Ambiente e Ordenamento, Aveiro, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Bock, Bettina Barbar. 2018. Rural Futures, Inclusive Rural Development in Times of Urbanization. Wageningen: Wageningen University. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bristow, Gillian. 2010. Resilient regions replaceing regional competitiveness. Cambridge Journal of Regions Economy and Society 3: 153–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bristow, Gillian, and Adrian Healy. 2014. Regional Resilience: An Agency Perspective. Regional Studies 48: 923–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, Rob J. F., and Geoff A. Wilson. 2006. Injecting social psychology theory into conceptualisations of agricultural agency: Towards a post-productivist farmer self-identity? Journal of Rural Studies 22: 95–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells-Quintana, David, and Vicente Royuela. 2018. Spatially blind policies? Analysing agglomeration economies and European Investment Bank funding in European neighbouring countries. Annals of Regional Science 60: 569–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celata, Filippo, and Raffaella Coletti. 2014. Place-based strategies or territorial cooperation? Regional development in transnational perspective in Italy. Local Economy 29: 394–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloke, Paul. 2006. Conceptualizing rurality. In Handbook of Rural Studies. Edited by Paul Cloke, Terry Marsden and Patrick Mooney. London: Sage, pp. 18–27. [Google Scholar]

- Daliakopoulos, Ioannis, and Ioannis Tsanis. 2014. CASCADE REPORT Series Dryland Ecosystems. Brussels: European Union. [Google Scholar]

- DG ADR. 2018. Available online: https://www.dgadr.gov.pt/ (accessed on 17 September 2017).

- Domínguez García, M. Dolores, Lummina Horlings, Paul Swagemakers, and Xavier Simón Fernández. 2013. Place branding and endogenous rural development. Departure points for developing an inner brand of the River Minho estuary. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy 9: 124–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos-Santos, Maria José Palma Lampreia, Rui Pedro Barreiro, José Manuel Teixeira Pereira, and Amélia Ferreira-da-Silva. 2014. Semi-subsistence farms in Portugal. Journal of Agricultural Economics and Development 3: 152–58. [Google Scholar]

- ECVC. 2015. How Can Public Policy Support Small-Scale Family Farms? Jakarta: European Cooperation, Via Campesina. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. 2015. Territorial Agenda 2020 Put in Practice—Enhancing the Efficiency and Effectiveness of Cohesion Policy by a Place-Based Approach (Synthesis Report, Volume I). Brussels: European Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Eusébio, Celeste, Maria João Carneiro, Elisabeth Kastenholz, Elisabete Figueiredo, and Diogo Soares da Silva. 2017. Who is consuming the countryside? An activity-based segmentation analysis of the domestic rural tourism market in Portugal. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 31: 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, Nick, Carol Morris, and Michael Winter. 2001. Conceptualising agriculture: A critique of post-productivism as the new orthodoxy. Progress in Human Geography 26: 313–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everett, Sally. 2012. Production Places or Consumption Spaces? The Place-making Agency of Food Tourism in Ireland and Scotland. Tourism Geographies 14: 535–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farole, Thomas, Andres Rodriguez-Pose, and Michael Storper. 2015. Cohesion policy in the European Union: Growth, geography, institutions. Journal of Common Market Studies 49: 1089–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, Elisabete. 2008. Imagine There’s No Rural: The Transformation of Rural Spaces into Places of Nature Conservation in Portugal. European Urban and Regional Studies 15: 159–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, Elisabete. 2013. Ch 9 McRural, No Rural or What Rural? Some reflections on rural reconfiguration processes based on the promotion of Schist villages network. In Shaping Rural Areas in Europe: Perceptions and Outcomes on the Present and the Future. Dordrecht: Geo Journal Library. ISBN 978-94-007-6795-9. [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo, Elisabete, and Antonio Raschi. 2012. Immersed in Green? Reconfiguring the Italian countryside through rural tourism promotional materials. In Field Guide for Case Study Research in Tourism, Hospitality and Leisure. Edited by Hyde K., Ryan C. and Woodside A. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited, pp. 17–44. [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo, Elisabete, and Antonio Raschi. 2013. Fertile Links? Connections between Tourism Activities, Socio-Economic Contexts and local Development in European Rural Areas. Florence: Firenze University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo, Elisabete, Candido Dionisio Pinto, Diogo Soares da Silva, and Catarina Capela. 2014. “No country for old people” Representations of the rural in the Portuguese tourism promotional campaigns. Ager Revista de Estudios Sobre Despoblación y Desarrollo Rural 17: 35–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcilazo, Jose Enrique, Joaquim Oliveira Martins, and William Tompson. 2010. Why Policies May Need to Be Place-Based in Order to Be People-Centred. Available online: https://voxeu.org/article/why-policies-may-need-be-place-based-order-be-people-centred (accessed on 7 July 2018).

- Gill, Indermit. 2010. Regional Development Policies: Place Based or People Centred. Available online: https://voxeu.org/article/regional-development-policies-place-based-or-people-centred (accessed on 20 July 2018).

- Gobattoni, Federica, Raffaele Pelorosso, Antonio Leone, and Maria Nicolina Ripa. 2015. Sustainable rural development: The role of traditional activities in Central Italy. Land Use Policy 48: 412–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinjoan, Eloi, Anna Badia, and Antoni F. Tulla. 2016. The new paradigm of rural development. Theoretical considerations and reconceptualization using the rural web. Boletín de La Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles No 71: 495–500. [Google Scholar]

- Halfacree, Keith. 2006. Rural space: Constructing a three-fold architecture. Handbook of Rural Studies. Local Economy 29: 44–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildreth, Paul, and David Bailey. 2014. Place-based economic development strategy in England: Filling the missing space. Local Economy 29: 363–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, John. 2006. Impulses towards a multifunctional transition in rural Australia: Gaps in the research agenda. Journal of Rural Studies 22: 142–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horlings, Lummina G. 2015a. The inner dimension of sustainability: Personal and cultural values. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 14: 163–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horlings, Lummina G. 2015b. Values in place; A value-oriented approach toward sustainable place-shaping. Regional Studies. Regional Science 2: 257–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horlings, Lummina G. 2016. Connecting people to place: Sustainable place-shaping practices as transformative power. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 20: 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horlings, Lummina G. 2018. Politics of Connectivity: The Relevance of Place-Based. In The SAGE Handbook of Nature. Edited by Terry Marsden. London: SAGE Publications Ltd., pp. 304–24. [Google Scholar]

- Horlings, Lummina G., and Yoko Kanemasu. 2015. Sustainable development and policies in rural regions; insights from the Shetland Islands. Land Use Policy 49: 310–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horlings, Lummina G., and Terry Marsden. 2014. Exploring the ‘New Rural Paradigm’ in Europe: Eco-economic strategies as a counterforce to the global competitiveness agenda. European Urban and Regional Studies 21: 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horlings, Lummina G., Roep Dirk, and Wellbrock Wiebke. 2018b. The role of leadership in place-based development and building institutional arrangements. Local Economy 33: 245–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística. 2016. Available online: https://portal-rpe01.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_main (accessed on 28 November 2016).

- Jauhiainen, Jussi S., and Helka Moilanen. 2011. Towards fluid territories in European spatial development: Regional development zones in Finland. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 29: 728–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jollivet, Marcel. 1997. Des campagnes paysannes au rural ‘vert’: Naissance d’une ruralité postindustriel. In Vers un Rural Postindustriel—Rural et Environnement en Huit Pays Européens. Edited by Marcel Jollivet. Paris: L’Harmattan, pp. 77–126. [Google Scholar]

- Kahirul, Baharein Mohd noor. 2008. Case Study: A Strategic Research Methodology. American Journal of Applied Sciences 5: 1602–4. [Google Scholar]

- Marsden, Terry. 1995. Beyond agriculture? Regulating the new rural spaces. Journal of Rural Studies 11: 285–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marta-Costa, Ana, and Emiliana Silva. 2015. Global Overview of the Rural Development Programme: The Mainland Portugal Case-Study. Newport: Harper Adams University. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, Doreen. 2005. For Space. London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Mendez, Carlos. 2011. EU Cohesion Policy and Europe 2020: Between place-based and people-based prosperity. Paper presented at the RSA Cohesion Policy Network Conference, Vienna, Austria, November 29–30; pp. 29–30. [Google Scholar]

- Neumark, David, and Helen Simpson. 2014. Place-Based Policies. Nber Working Paper Series; London: Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2009. Regions Matter, Economic Recovery, Innovation and Sustainable Growth. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. ISBN 978-92-64-07652-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2014. New Rural Policy: Linking up for growth. Paper presented at National Prosperity through Modern Rural Policy Conference, Memphis, TN, USA, May 19–21. [Google Scholar]

- Olfert, M. Rose, Mark Partridge, Julio Berdegué, Javier Escobal, Benjamin Jara, and Felix Modrego. 2014. Places for place-based policy. Development Policy Review 32: 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, Fernando Oliveira. 2006. O rural depois da agricultura. In Desenvolvimento e Território–Espaços Rurais Pós-agrícolas e os Novos Lugares de Turismo e Lazer. Edited by Fonseca M. L. Lisbon: Centro de Estudos Geográficos, pp. 85–100. [Google Scholar]

- Pato, Lucia, Zelia Breda, and Vitor Figueiredo. 2015. Women’s entrepreneurship and local sustainability: The case study of a Portuguese rural initiative. Revista Turismo & Desenvolvimento/Journal of Tourism & Development 23: 119–28. [Google Scholar]

- Pugalis, Lee, and Gill Bentley. 2014a. (Re) appraising place-based economic development strategies. Local Economy 29: 273–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugalis, Lee, and Gill Bentley. 2014b. Place-based development strategies: Possibilities, dilemmas and ongoing debates. Local Economy 29: 561–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugalis, Lee, and Nick Gray. 2016. New regional development paradigms: An exposition of place-based modalities. Australasian Journal of Regional Studies 22: 2–4. [Google Scholar]

- Roep, Dirk, Wiebke Wellbrock, and Lummina GHorlings. 2015. Raising Self-efficacy and Resilience in the Westerkwartier: The Spin-off from Collaborative Leadership. In Globalization and Europe’s Rural Region. Edited by McDonagh Nienaber. Woods: Ashgate Publisher, Chp. 3. pp. 41–58. [Google Scholar]

- Obe, Mark Shucksmith. 2006. First European Quality of Life Survey: Urban-rural Differences. European Foundation for the Improving of Living and Working Conditions. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, Luis, and Elisabete Figueiredo. 2013. Ch1 What Is Shaping Rural Areas in Europe? Introduction. In Shaping Rural Areas in Europe. Dordrecht: Geo Journal Library, pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Soares da Silva, Diogo, Elisabete Figueiredo, Celeste Eusébio, and Maria João Carneiro. 2016. The countryside is worth a thousand words—Portuguese representations on rural areas. Journal of Rural Studies 44: 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaney, John. 2010. Place-Based Trends and Approaches to Regional Development: Global Australian Implications. Sydney: Australian Business Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Ploeg, Jan Douwe, Henk Renting, Gianluca Brunori, Karlheinz Knickel, Joe Mannion, Terry Marsden, and Flaminia Ventura. 2000. Rural Development: From Practices and Policies towards Theory. Sociologia Ruralis 40: 392–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Ploeg, Jan Douwe, Rudolf van Broekhuizen, Gianluca Brunori, Roberta Sonnino, Karlheinz Knickel, Talis Tisenkops, and Henk Oostendie. 2008. Towards a framework for understanding regional rural development. Unfolding Webs: The Dynamics of Regional Rural Development. pp. 1–28. Available online: http://orca.cf.ac.uk/20526/ (accessed on 5 October 2017).

- Varga, Attila. 2017. Place-based, Spatially Blind, or Both? Challenges in Estimating the Impacts of Modern Development Policies: The Case of the GMR Policy Impact Modeling Approach. International Regional Science Review 40: 12–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasta, Attila, and Elisabete Figueiredo. 2018. Weaving tradition with innovation. In Brief Reflections on the Importance of Innovation in Rural Areas. Ch7 in Book: Várzea de Calde, a Village Woven in Linen. Viseu: Edições-Nodar. ISBN 978-989-99856-1-2. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, Geoff A. 2001. From productivism to post-productivism...and back again? Exploring the (un) changed natural and mental landscapes of European. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 26: 77–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Geoff A., and Rob J. F. Burton. 2015. “Neo-productivist” agriculture: Spatio-temporal versus structuralist perspectives. Journal of Rural Studies 38: 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, Michael. 2007. Engaging the global countryside: Globalization, hybridity and the reconstitution of rural place. Progress in Human Geography 31: 485–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. 2009. World Development Report, Reshaping Economic Geography. Washington: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | LEADER is an acronym in French of Liaison entre actions de développement de l’économie rurale—meaning Links between actions for the development of the rural economy. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).