What Helps and What Hinders? Exploring the Role of Workplace Characteristics for Parental Leave Use and Its Career Consequences

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Parental Leave and Gender Inequality

2.2. Fathers’ Use of Parental Leave

2.3. Organizations and Gender Inequality in Parental Leave Use

2.4. Germany as a Research Setting

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Quantitative Data and Analyses

3.2. Qualitative Data and Analyses

4. Results

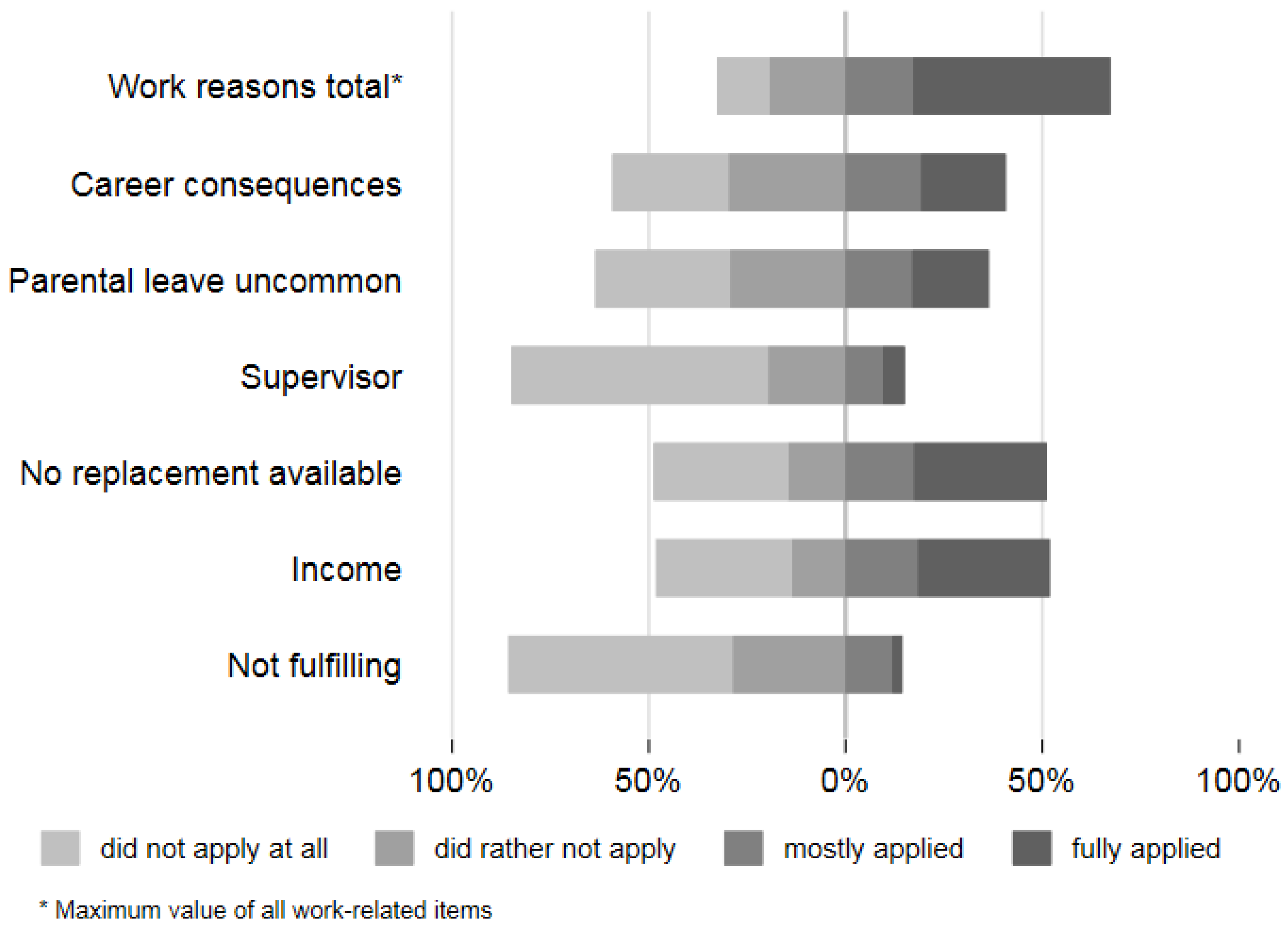

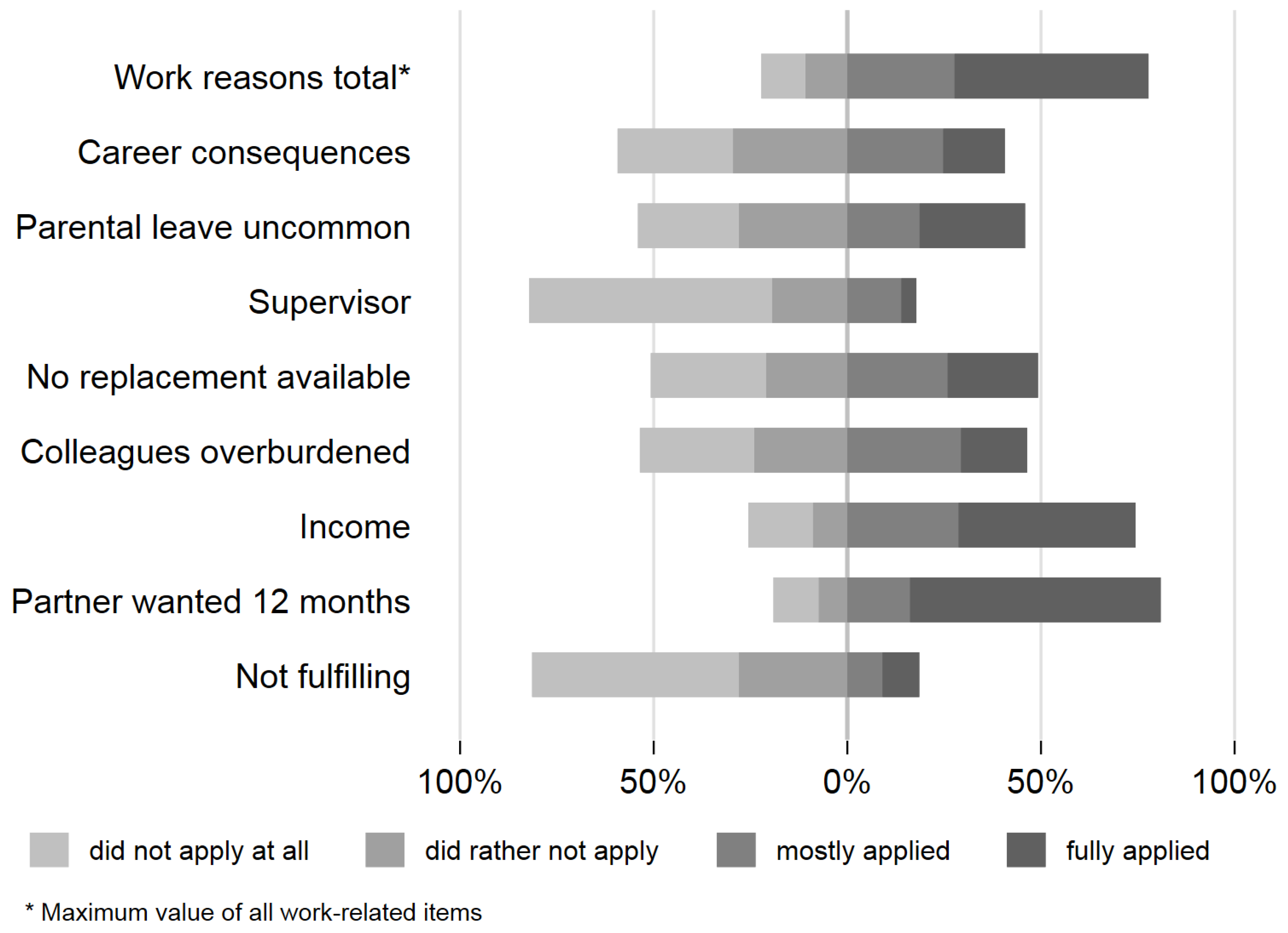

4.1. Fathers’ Reasons for Not Taking (Longer) Parental Leave

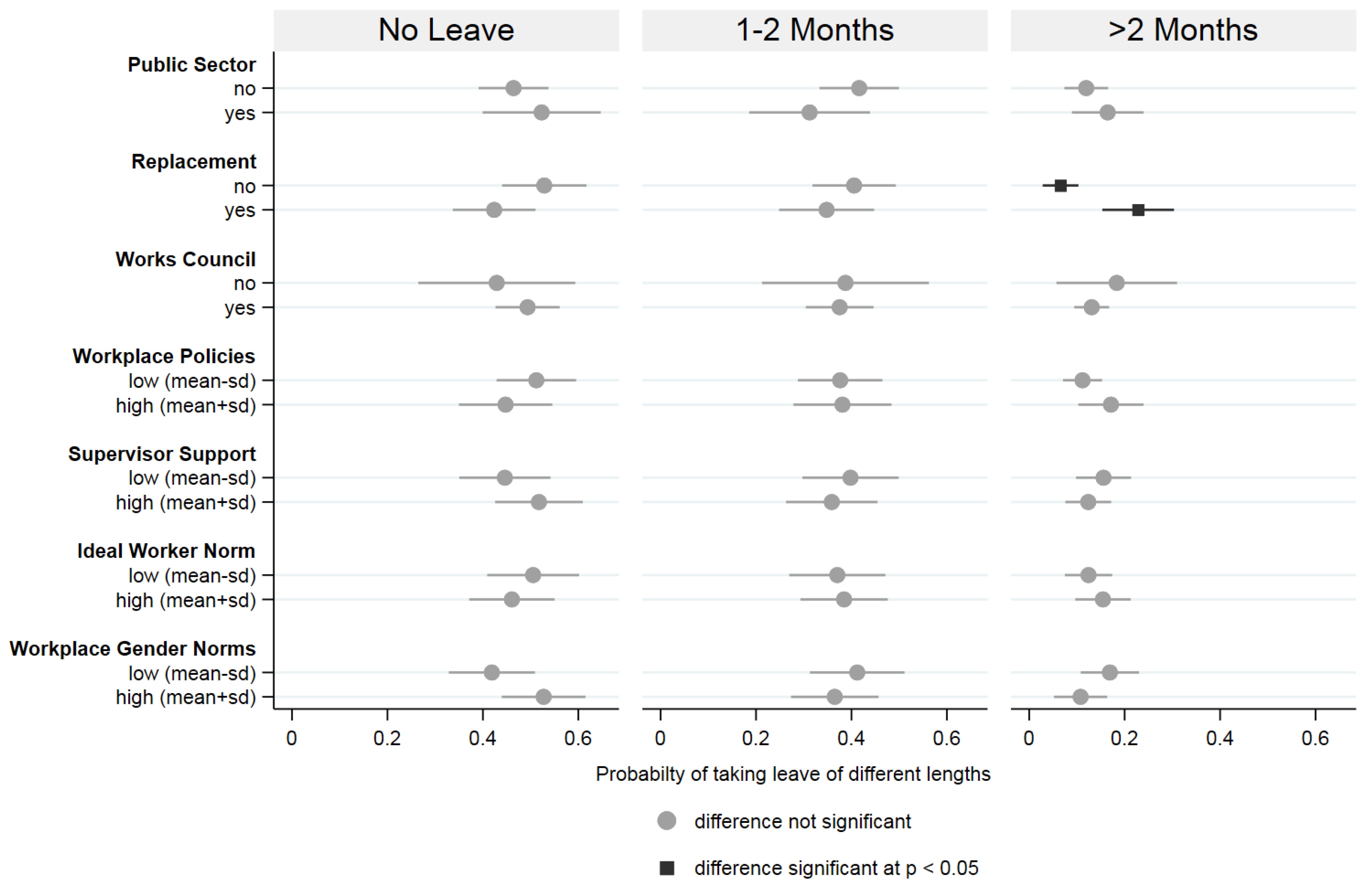

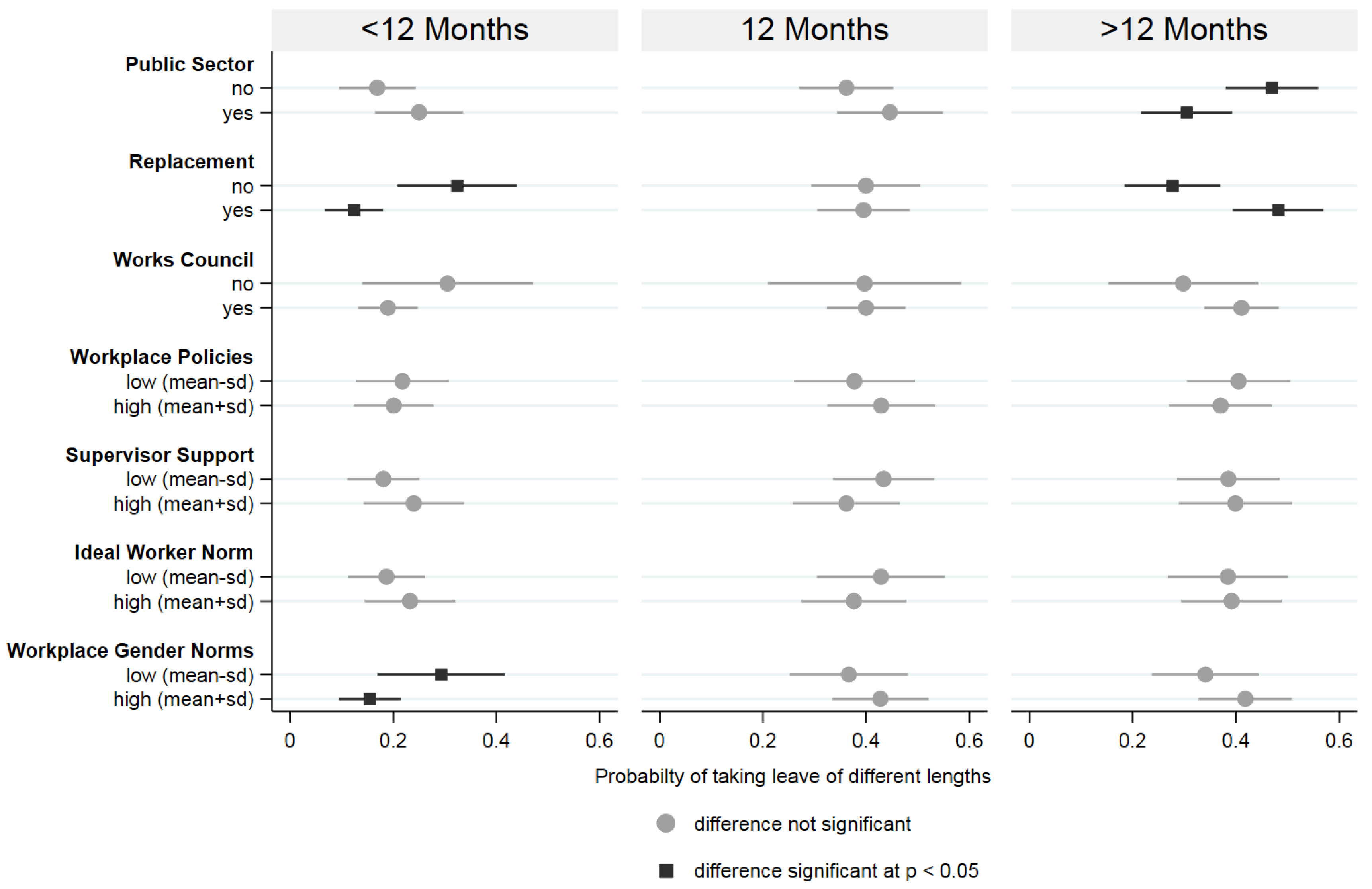

4.2. Workplace Characteristics and Fathers’ and Mothers’ Leave Durations

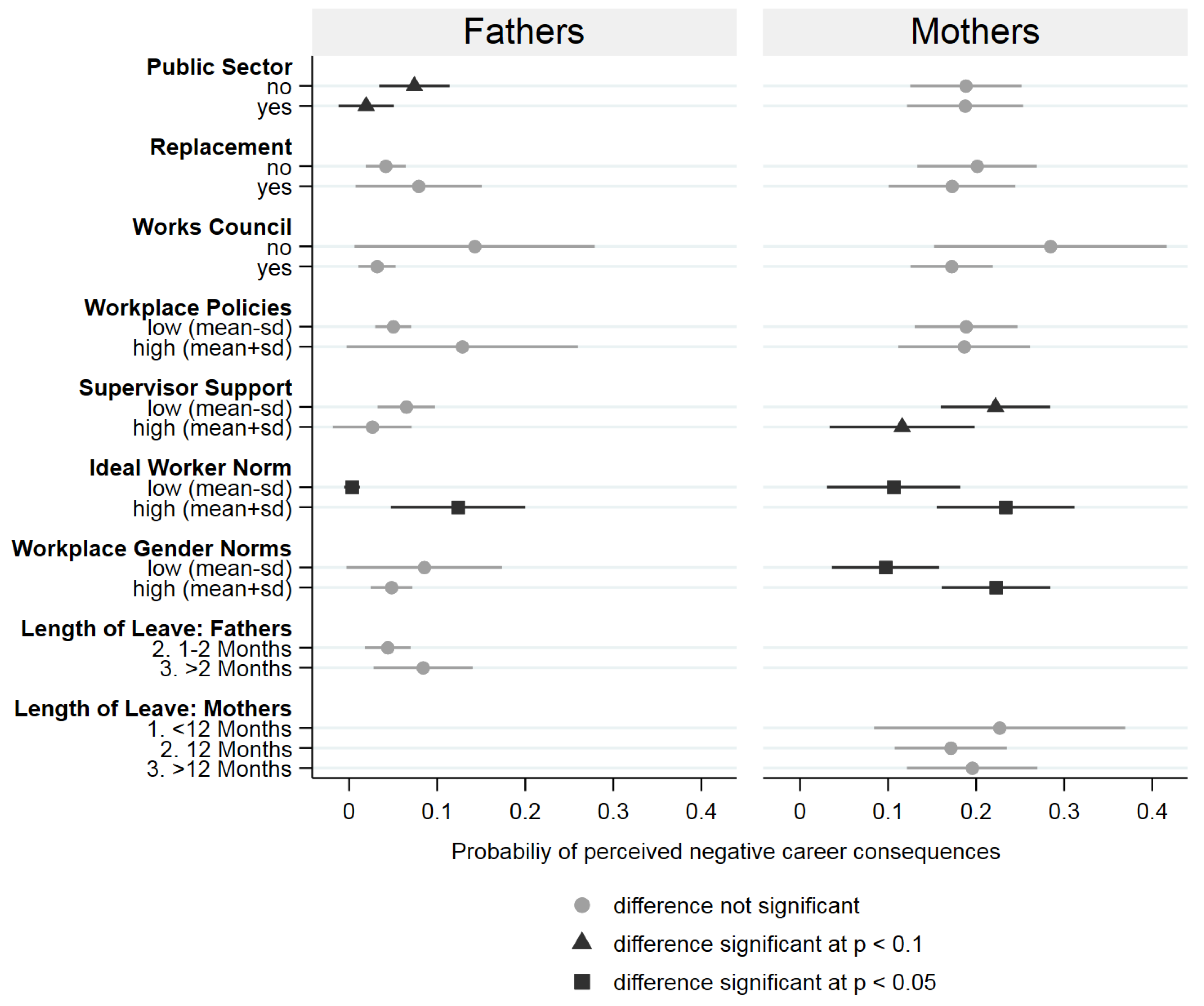

4.3. Consequences of Parental Leave for Fathers’ and Mothers’ Professional Careers

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| DEPENDENT VARIABLES | ||

|---|---|---|

| Reasons for not taking parental leave | ||

| Why didn’t you take parental leave? Please tell me which of the following statements “fully applied”/“mostly applied”/“did rather not apply”/“did not apply at all” … I chose not to take leave because of financial reasons. … The leave would have harmed my career. … Only taking care of the child would not have been fulfilling for me. … My supervisor was against it. … In my company it was uncommon for men to take parental leave. … There was no replacement available for my tasks. | ||

| Reasons for not taking longer leave | ||

| Why didn’t you take longer parental leave? Please tell me which of the following statements “fully applied”/“mostly applied”/“did rather not apply”/“did not apply at all” … I chose not to take longer leave because of financial reasons. … A longer leave would have harmed my career. … Only taking care of the child would not have been fulfilling for me. … My supervisor was against it. … In my company it was uncommon for men to more than two months of leave. … My partner wanted to take at least 12 months of leave. … There was no replacement available for my tasks. … A longer leave would have overburdened my colleagues. | ||

| Duration of leave taken | ||

| How many months of parental leave did you take for your youngest child? (0–36 months) Categorical variables Men: 0 month; 1–2 months; >2 months Women: <12 months; 12 months; >12 months | ||

| Negative Career Consequences (Dummy) | ||

| What consequences did your parental leave have on your career? Did the leave … … help the career … harm the career … or did it have no impact at all 0 = help the career or no impact at all; 1 = harm the career | ||

| MAIN INDEPENDENT VARIABLES - WORKPLACE CHARACTERISTICS | ||

| Public Sector (Dummy) | ||

| Replacement (Dummy) | ||

| When you have to leave work early or when you are absent, do your colleagues cover for you or does your work remain undone? 0 = work remains undone; 1 = colleagues cover for me | ||

| Firm Size 0 =<20 employees; 1 = 20 to 249 employees; 2 = 250+ employees | ||

| Works Council (Dummy) | ||

| Degree of family-friendly workplace regulation (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.84) Based on five items rated from 0 = do not agree at all to 10 = agree completely | Botsch et al. (2007) | |

| Balancing family and work is a private matter. (inverted) The management is committed to the needs of employees and their families. There are official policies on balancing family and work. Policies, for instance, on working from home or flexible working hours, apply to all employees. Employees are informed about family-friendly policies. | ||

| Support from supervisor (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.81) Based on four items rated from 0 = do not agree at all to 10 = agree completely | Hammer et al. (2009); Harrington et al. (2011); Pfahl et al. (2014) | |

| My supervisor respects my private life. My supervisor has a lot of understanding for my family situation. My supervisor assists me in advancing my career. My supervisor demonstrates how a person can jointly be successful on and off the job. | ||

| Gender Roles at the Workplace (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.65) Based on three items rated from 0 = do not agree at all to 10 = agree completely | Gärtner (2012) | |

| In my company the common opinion is that women are supposed to back their partners up at home. In my company, child care is regarded as a women’s task. In my company the common opinion is that fathers should take parental leave after the birth of their child, too. (inverted) | ||

| Ideal Worker Norm (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.78) Based on four items rated from 0 = do not agree at all to 10 = agree completely | Booth and Matthews (2012) | |

| Employees who are highly committed to their personal lives cannot be highly committed to their work. It is assumed that the most productive employees are those who put their work before their family life. The way to advance is to keep non-work matters out of the workplace. Attending to personal needs, such as taking time off for sick children is frowned upon. | ||

| CONTROLS | ||

| Age, marital status, tertiary education, partner’s tertiary education, number of children, birth year youngest child (as a proxy for time since the introduction of reform), region, professional position, fixed-term contract | ||

| Full Sample | Stable Employer | Parental Leave Users | Reported Negative Consequences | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 42.66 | 42.63 | 41.67 | 39.47 |

| Married | 0.86 | 0.85 | 0.86 | 1.00 |

| Tertiary education | 0.54 | 0.55 | 0.56 | 0.74 |

| Partner tertiary education | 0.47 | 0.47 | 0.62 | 0.96 |

| Number of Children | 1.87 | 1.93 | 1.75 | 2.15 |

| Age youngest child | 4.23 | 3.95 | 3.00 | 2.04 |

| Region: West | 0.83 | 0.85 | 0.80 | 0.91 |

| Professional position | 0.68 | 0.70 | 0.76 | 0.80 |

| Temporary contract | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.00 |

| Observations | 586 | 453 | 206 | 18 |

| Full Sample | Stable Employer | Parental Leave Users | Reported Negative Consequences | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 40.15 | 40.51 | 40.42 | 41.50 |

| Married | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.63 |

| Tertiary education | 0.50 | 0.51 | 0.52 | 0.46 |

| Partner tertiary education | 0.53 | 0.53 | 0.53 | 0.40 |

| Number of Children | 1.63 | 1.62 | 1.62 | 1.51 |

| Age youngest child | 4.79 | 4.54 | 4.48 | 4.24 |

| Region: West | 0.77 | 0.80 | 0.79 | 0.83 |

| Professional position | 0.66 | 0.69 | 0.68 | 0.49 |

| Temporary contract | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.02 |

| Observations | 484 | 333 | 305 | 52 |

| Interview Characteristics | ||

| Number of Interviews | N = 44 | |

| Field period | December 2014–January 2015 | |

| Interview Duration | Ø 1.5 h | |

| Sociodemographic Interviewee and Organizational Characteristics | ||

| Number of Children | Ø 1.84 children (national average 1.5 children) * | |

| Seniority | Ø 10.6 years (range 0.25 (min)−29 (max)) | |

| Public Sector | Abs. | Proportion (%) |

| Yes No | 58 (Individuals) 30 | 66% 34% |

| Works Council | ||

| Yes No | 65 (Individuals) 23 | 74% 26% |

| Occupational Arrangements | ||

| PTFT (Father Part-Time/Mother Full-Time) FTPT (Father Full-Time/Mother Part-Time) FTFT (Father Full-Time/Mother Full-Time) PTPT (Father Part-Time/Mother Part-Time) | 8 (Couples) 13 11 12 | 18% 30% 25% 27% |

| Parental Leave Distribution | ||

| ‘Solo Parental Leave: Mother’ ‘New Leave Norm 12 + 2’ ‘Main Leave Taker: Mother’ ‘Egalitarian’ ‘Employment-Oriented’ ‘Main Leave Taker: Father’ | 12 (Couples) 16 2 3 7 4 | 27% 36% 5% 7% 16% 9% |

| Education | ||

| Tertiary Education Up to Secondary Education | 50 (Individuals) 38 | 57% 43% |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married Cohabitating | 36 (Couples) 8 | 82% 18% |

| Region | ||

| West East | 34 (Couples) 10 | 77% 23% |

| No Leave | Fathers 1–2 Months | >2 Months | No Leave | Fathers 1–2 Months | >2 Months | <12 Months | Mothers 12 Months | >12 Months | <12 Months | Mothers 12 Months | >12 Months | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | |||||||||

| Age | −0.01 | 0.01 * | −0.01 (*) | −0.01 | 0.01 * | −0.01 (*) | −0.01 | −0.00 | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.00 | 0.01 |

| Married | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.00 | −0.00 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.06 | −0.10 | 0.04 | 0.07 | −0.10 | 0.04 |

| Tertiary education | 0.10 | 0.02 | −0.13 ** | 0.10 | 0.01 | −0.11 * | 0.01 | 0.12 | −0.13 | 0.01 | 0.12 | −0.13 |

| Partner tertiary education | −0.27 *** | 0.12 (*) | 0.15 *** | −0.26 *** | 0.13 (*) | 0.14 ** | 0.02 | −0.14 (*) | 0.12 | 0.00 | −0.13 (*) | 0.13 (*) |

| Number of children | 0.14 *** | −0.13 ** | −0.02 | 0.14 *** | −0.13 ** | −0.02 | 0.00 | −0.07 | 0.07 | 0.01 | −0.08 | 0.07 |

| Birth year youngest child | −0.07 *** | 0.06 *** | 0.00 | −0.07 *** | 0.07 *** | 0.00 | −0.02 | 0.05 ** | −0.04 * | −0.02 | 0.05 ** | −0.03 * |

| West Germany | 0.15 (*) | −0.13 | −0.03 | 0.13 (*) | −0.11 | −0.03 | 0.08 | −0.13 | 0.06 | 0.08 | −0.12 | 0.04 |

| Professional position | −0.09 | −0.07 | 0.16 *** | −0.11 | −0.04 | 0.15 *** | 0.04 | −0.10 | 0.06 | 0.04 | −0.10 | 0.07 |

| Fixed−term | 0.05 | −0.23 (*) | 0.18 (*) | 0.08 | −0.22 | 0.14 | 0.13 | −0.43 *** | 0.30 * | 0.13 | −0.43 *** | 0.30 (*) |

| Public sector | 0.06 | −0.09 | 0.03 | 0.06 | −0.10 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.07 | −0.14 * | 0.08 | 0.08 | −0.17 * |

| Replacement | −0.10 | −0.06 | 0.16 *** | −0.10 | −0.06 | 0.16 *** | −0.20 ** | −0.01 | 0.20 ** | −0.20 ** | −0.00 | 0.20 ** |

| Firm size < 20 | 0.05 | 0.07 | −0.12 * | 0.17* | −0.12 | −0.05 | ||||||

| Firm size 250+ | −0.06 | 0.15 * | −0.09 * | 0.06 | −0.05 | −0.00 | ||||||

| Works council | 0.06 | −0.01 | −0.05 | −0.12 | 0.00 | 0.11 | ||||||

| Workplace policies | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.00 | 0.01 | −0.01 | ||||||

| Supervisor support | 0.02 | −0.01 | −0.00 | 0.02 | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.00 |

| Workplace gender norms | 0.02 | −0.01 | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.03 (*) | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.03 * | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Ideal worker norm | −0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.00 |

| N | 369 | 369 | 369 | 369 | 369 | 369 | 291 | 291 | 291 | 291 | 291 | 291 |

| pseudo R2 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.18 | 0.18 | ||||||||

| Fathers | Mothers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | |

| Age | −0.00 | −0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Married | 0.05 *** | 0.05 *** | −0.16 * | −0.14 (*) |

| Tertiary education | 0.07 (*) | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.08 |

| Partner tertiary education | 0.07 * | 0.06* | −0.03 | −0.06 |

| Number of children | 0.02 | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.02 |

| Birth year youngest child | −0.01 | −0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| West Germany | 0.05 (*) | 0.04 * | −0.05 | −0.02 |

| Professional position | −0.00 | 0.02 | −0.18 * | −0.20 ** |

| Fixed-term | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.17 *** | −0.18 *** |

| Public sector | −0.09 *** | −0.05 (*) | −0.04 | −0.00 |

| Replacement | 0.01 | 0.04 | −0.01 | −0.03 |

| Firm size < 20 | −0.04 | −0.02 | ||

| Firm size 250+ | −0.03 | 0.10 (*) | ||

| Works council | −0.11 | −0.11 | ||

| Workplace policies | 0.01 | −0.00 | ||

| Supervisor support | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.03 (*) | −0.02 (*) |

| Workplace gender norms | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.03 * | 0.03 ** |

| Ideal worker norm | 0.03 * | 0.03 ** | 0.02 | 0.02 * |

| >2 months leave | 0.04 | 0.04 | ||

| <12 months leave | 0.04 | 0.06 | ||

| >12 months leave | −0.00 | 0.02 | ||

| N | 162 | 162 | 257 | 257 |

| pseudo R2 | 0.46 | 0.51 | 0.38 | 0.38 |

References

- Acker, Joan. 1990. Hierarchies, Jobs, Bodies: A Theory of Gendered Organizations. Gender and Society 4: 139–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acker, Joan. 1992. From sex roles to gendered institutions. Contemporary Sociology 21: 565–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aisenbrey, Silke, Marie Evertsson, and Daniela Grunow. 2009. Is There a Career Penalty for Mothers’ Time Out? A Comparison of Germany, Sweden and the United States. Social Forces 88: 573–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almqvist, Anna-Lena, and Ann-Zofie Duvander. 2014. Changes in Gender Equality? Swedish Fathers’ Parental Leave, Division of Childcare and Housework. Journal of Family Studies, 3539–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Cynthia, and Donald Tomaskovic-Devey. 1995. Patriarchal Pressures: An Exploration of Organizational Processes that Exacerbate and Erode Gender Earnings Inequality. Work and Occupations 22: 328–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aunkofer, Stefanie, Michael Meuser, and Benjamin Neumann. 2018. Couples and Companies: Negotiating Fathers’ Participation in Parental Leave in Germany. Revista Española de Sociología 27: 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, James N., and William T. Bielby. 1980. Bringing the firms back in: Stratification, segmentation, and the organization of work. American Sociological Review 45: 737–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benard, Stephen, and Shelley J. Correll. 2010. Normative Discrimination and the Motherhood Penalty. Gender & Society 24: 616–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, Lawrence M., Jennifer Hill, and Jane Waldfogel. 2005. Maternity Leave, Early Maternal Employment and Child Health and Development in the US. The Economic Journal 115: F29–F47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhardt, Janine, and Mareike Bünning. 2019. Fathers’ working times in Germany: What role do cultural and structural workplace conditions play? In The New Ideal Worker: Organizations between Work-Life Balance, Gender and Leadership. Edited by Mireia las Heras Maestro, Nuria Chinchilla Albiol and Marc Grau. Cham: Springer, pp. 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhardt, Janine, Lena Hipp, and Jutta Allmendinger. 2016. Warum Nicht Fifty-Fifty? Betriebliche Rahmenbedingungen der Aufteilung von Erwerbs- und Fürsorgearbeit in Paarfamilien. Discussion Paper, SP I 2016–501. Berlin: Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung. [Google Scholar]

- Bielby, William T., and James N. Baron. 1986. Men and women at work: Sex segregation and statistical discrimination. The American Journal of Sociology AJS 91: 759–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørnholt, Margunn, and Gunhild R. Farstad. 2014. ‘Am I rambling?’ on the advantages of interviewing couples together. Qualitative Research 14: 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair-Loy, Mary. 2003. Competing Devotions: Career and Family among Women Executives. [Reprint d. Ausg.:]. Cambridge: Harvard Univ. Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bloksgaard, Lotte. 2015. Negotiating Leave in the Workplace: Leave Practices and Masculinity Constructions among Danish fathers. In Fatherhood in the Nordic Welfare States: Comparing Care Policies and Practice. Edited by Guðný Björk Eydal and Tine Rostgaard. Bristol: Policy Press, pp. 141–61. [Google Scholar]

- Blum, Sonja, Alison Koslowski, Alexandra Macht, and Peter Moss. 2018. International Review of Leave Policies and Research 2018. Available online: http://www.leavenetwork.org/lp_and_r_reports/ (accessed on 12 August 2019).

- BMFSFJ. 2007. Das Elterngeld im Urteil der jungen Eltern. Eine Umfrage unter Müttern und Vätern, Deren Jüngstes Kind 2007 Geboren Wurde. Bonn: Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend. [Google Scholar]

- BMFSFJ. 2018a. Elterngeld, ElterngeldPlus und Elternzeit: Das Bundeselterngeld- und Elternzeitgesetz. Berlin: BMFSFJ. [Google Scholar]

- BMFSFJ. 2018b. Väterreport: Vater Sein in Deutschland Heute. Berlin: BMFSFJ. [Google Scholar]

- Boeckmann, Irene, Joya Misra, and Michelle Budig. 2015. Cultural and Institutional Factors Shaping Mothers’ Employment and Working Hours in Postindustrial Countries. American Sociological Review 93: 1301–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, Suzanne M., and Russel A. Matthews. 2012. Family-supportive organization perceptions: Validation of an abbreviated measure and theory extension. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 17: 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botsch, Elisabeth, Christiane Lindecke, and Alexandra Wagner. 2007. Familienfreundlicher Betrieb: Einführung, Akzeptanz und Nutzung von familienfreundlichen Maßnahmen. Eine empirische Untersuchung. Düsseldorf: Hans-Böckler-Stiftung. [Google Scholar]

- Britton, Dana M. 2003. At Work in the Iron Cage: The Prison as Gendered Organization. New York and London: NYU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brumley, Krista M. 2014. The Gendered Ideal Worker Narrative. Gender & Society 28: 799–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, Alan. 2006. Integrating quantitative and qualitative research: How is it done? Qualitative Research 6: 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budig, Michelle, Joya Misra, and Irene Boeckmann. 2016. Work–Family Policy Trade-Offs for Mothers? Unpacking the Cross-National Variation in Motherhood Earnings Penalties. Work and Occupations 43: 119–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bünning, Mareike. 2015. What Happens after the ‘Daddy Months’?: Fathers’ Involvement in Paid Work, Childcare, and Housework after Taking Parental Leave in Germany. European Sociological Review 31: 738–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bünning, Mareike. 2016. Die Vereinbarkeitsfrage für Männer: Welche Auswirkungen haben Elternzeiten und Teilzeitarbeit auf die Stundenlöhne von Vätern? KZfSS Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 68: 597–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bygren, Magnus, and Ann-Zofie Duvander. 2006. Parents’ Workplace Situation and Fathers’ Parental Leave Use. Journal of Marriage and Family 68: 363–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, Caitlyn. 2019. Making Motherhood Work: How Women Manage Careers and Caregiving. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coltrane, Scott, Elizabeth C. Miller, Tracy DeHaan, and Lauren Stewart. 2013. Fathers and the Flexibility Stigma. Journal of Social Issues 69: 279–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, John W., Vicki L. Plano Clark, Michelle L. Gutmann, and William E. Hanson. 2007. Advanced Mixed Methods Research Designs. In Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social & Behavioral Research. [Nachdr.]. Edited by Abbas Tashakkori and Charles Teddlie. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publ., pp. 209–40. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Andrea R., and Brenda D. Frink. 2014. The Origins of the Ideal Worker: The Separation of Work and Home in the United States from the Market Revolution to 1950. Work and Occupations 41: 18–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvander, Ann-Zofie, and Linda Haas. 2018. Sweden country note. In 14th International Review of Leave Policies and Related Research 2018. Edited by Sonja Blum, Alison Koslowski, Alexandra Macht and Peter Moss. pp. 401–10. Available online: http://www.leavenetwork.org/lp_and_r_reports/ (accessed on 12 August 2019).

- Erler, Daniel. 2011. Germany. Taking a Nordic turn? In The Politics of Parental Leave Policies. Children, Parenting, Gender and the Labour Market. Edited by Sheila Kamerman and Peter Moss. Bristol: Bristol University Press, Policy Press, pp. 119–34. [Google Scholar]

- Escot, Lorenzo, José A. Fernández-Cornejo, Carmen Lafuente, and Carlos Poza. 2012. Willingness of Spanish Men to Take Maternity Leave. Do Firms’ Strategies for Reconciliation Impinge on This? Sex Roles 67: 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esping-Andersen, Gøsta. 1998. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Repr. Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press. [Google Scholar]

- Esping-Andersen, Gøsta. 2009. The Incomplete Revolution: Adapting to Women’s New Roles. Repr. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Evertsson, Marie. 2016. Parental leave and careers: Women’s and men’s wages after parental leave in Sweden. Advances in Life Course Research 29: 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evertsson, Marie, and Ann-Zofie Duvander. 2011. Parental Leave–Possibility or Trap? Does Family Leave Length Effect Swedish Women’s Labour Market Opportunities? European Sociological Review 27: 435–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evertsson, Marie, Katarina Boye, and Jeylan Erman. 2018. Fathers on call? A study on the sharing of care work between parents in Sweden. Demographic Research 39: 33–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eydal, Guðný B., and Ingólfur V. Gíslason. 2018. Iceland country note. In 14th International Review of Leave Policies and Related Research 2018. Edited by Sonja Blum, Alison Koslowski, Alexandra Macht and Peter Moss. pp. 205–11. Available online: http://www.leavenetwork.org/lp_and_r_reports/ (accessed on 12 August 2019).

- Fegert, Jörg M., Hubert Liebhardt, Jörg Althammer, Alexandra Baronsky, Fabienne Becker-Stoll, Tanja Besier, Dorothea Dette-Hagenmeyer, Andreas Eickhorst, Irene Gerlach, Gabriele Gloger-Tippelt, and et al. 2011. Vaterschaft und Elternzeit: Eine interdisziplinäre Literaturstudie zur Frage der Bedeutung der Vater-Kind-Beziehung für eine gedeihliche Entwicklung der Kinder sowie den Zusammenhalt in der Familie. Berlin: BMFSFJ. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, Kathy E. 1984. The Feminist Case against Bureaucracy. Philadelphia: Temple Univ. Pr. [Google Scholar]

- Gangl, Markus, and Andrea Ziefle. 2015. The Making of a Good Woman: Extended Parental Leave Entitlements and Mothers’ Work Commitment in Germany. American Journal of Sociology 121: 511–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gärtner, Marc. 2012. Männer und Familienvereinbarkeit: Betriebliche Personalpolitik, Akteurskonstellationen und Organisationskulturen. Opladen: Budrich UniPress Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Geisler, Esther, and Michaela Kreyenfeld. 2018. Policy Reform and Fathers’ Use of Parental Leave in Germany: The Role of Education and Workplace Characteristics. Journal of European Social Policy 46: 273–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorman, Elizabeth H., and Sarah Mosseri. 2019. How organizational characteristics shape gender difference and inequality at work. Sociology Compass 13: e12660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gornick, Janet C., and Marcia K. Meyers. 2003. Families That Work: Policies for Reconciling Parenthood and Employment. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, Jennifer C. 2007. Mixed Methods in Social Inquiry, 1st ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Grund, Christian, and Andreas Schmitt. 2011. Works councils, wages and job satisfaction. Applied Economics 45: 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, Linda, Karin Allard, and Philip Hwang. 2002. The Impact of Organizational Culture on Men’s Use of Parental Leave in Sweden. Community, Work & Family 5: 319–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, Linda, and Philip Hwang. 2019. Policy is not enough—The influence of the gendered workplace on fathers’ use of parental leave in Sweden. Community, Work & Family 22: 58–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, Leslie B., Ellen E. Kossek, Nanette L. Yragui, Todd E. Bodner, and Ginger C. Hanson. 2009. Development and validation of a multidimensional measure of family supportive supervisor behaviors (FSSB). Journal of Management 35: 837–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrington, Brad, Fred van Deusen, and Beth Humberd. 2011. The New Dad: Caring, Committed and Conflicted. Newton: Center for Work and Family. [Google Scholar]

- Hegewisch, Ariane, and Janet C. Gornick. 2011. The impact of work-family policies on women’s employment: A review of research from OECD countries. Community, Work & Family 14: 119–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hipp, Lena. 2016. Insecure times? Workers’ perceived job and labor market security in 23 OECD countries. Social Science Research 60: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hipp, Lena. 2018. Damned if you do, damned if you don’t? Experimental evidence on hiring discrimination against parents with differing lengths of family leave. SocArXiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holst, Elke, and Jürgen Schupp. 2003. Sicherheit des Arbeitsplatzes häufig mit Interessensvertretung im Betrieb verbunden: Wechselwirkungen zwischen Interessensvertretung und Strukturmerkmalen abhängig Beschäftigter. DIW Wochenbericht 70: 176–81. [Google Scholar]

- Hook, Jennifer L. 2006. Care in Context: Men’s Unpaid Work in 20 Countries, 1965–2003. American Sociological Review 71: 639–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta, Maria C., Willem Adema, Jennifer Baxter, Wen-Jui Han, Mette Lausten, RaeHyuck Lee, and Jane Waldfogel. 2013. Fathers’ Leave, Fathers’ Involvement and Child Development: Are They Related? Evidence from Four OECD Countries. Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 140. Paris: OECD. [Google Scholar]

- Jaumotte, Florence. 2004. Labour Force Participation of Women: Empirical Evidence on The Role of Policy And other Determinants in OECD Countries. OECD Economic Studies 2003: 53–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalev, Alexandra. 2009. Cracking the Glass Cages? Restructuring and Ascriptive Inequality at Work. American Journal of Sociology 114: 1591–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanter, Rosabeth Moss. 1977. Men and Women of the Corporation. [Nachdr.]. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Karu, Marre. 2012. Parental leave in Estonia: Does familization of fathers lead to defamilization of mothers? NORA-Nordic Journal of Feminist and Gender Research 20: 94–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karu, Marre, and Kairi Kasearu. 2011. Slow steps towards dual earner/dual carer family model: Why fathers do not take parental leave. Studies of Transition States and Societies 3: 24–38. [Google Scholar]

- Karu, Marre, and Diane-Gabrielle Tremblay. 2018. Fathers on parental leave: An analysis of rights and take-up in 29 countries. Community, Work & Family 21: 344–62. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, Gayle. 2018. Barriers to equality: Why British fathers do not use parental leave. Community, Work & Family 21: 310–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kmec, Julie A. 2005. Setting Occupational Sex Segregation in Motion. Work and Occupation 32: 322–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotey, Bernice, and Peter Slade. 2005. Formal Human Resource Mangement Practices in Small Growing Firms. Journal of Small Business Management 43: 16–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuckartz, Udo, Thorsten Dresing, Stefan Rädiker, and Claus Stefer. 2008. Qualitative Evaluation: Der Einstieg in die Praxis. 2. aktualisierte Auflage. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften/GWV Fachverlage GmbH Wiesbaden. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb, Michael E., ed. 2004. The Role of the Father in Child Development, 4th ed. Hoboken: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Lammi-Taskula, Johanna. 2007. Parental Leave for Fathers?: Gendered Conceptions and Practices in Families with Young Children in Finland. Ph.D. Thesis, Tampere University, Tampere, Finland. [Google Scholar]

- Lappegård, Trude. 2008. Changing the Gender Balance in Caring: Fatherhood and the Division of Parental Leave in Norway. Population Research and Policy Review 27: 139–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lappegård, Trude. 2012. Couples’ Parental Leave Practices: The Role of the Workplace Situation. Journal of Family and Economic Issues 33: 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leira, Arnlaug. 2011. Combining work and family: Nordic policy reforms in the 1990s. In Gender, Welfare State and the Market: Towards a New Division of Labour. Edited by Thomas P. Boje. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Jane. 2010. Work-Family Balance, Gender and Policy. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. [Google Scholar]

- Lott, Yvonne, and Christina Klenner. 2018. Are the ideal worker and ideal parent norms about to change? The acceptance of part-time and parental leave at German workplaces. Community, Work & Family 21: 564–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayring, Philipp. 2014. Qualitative Content Analysis: Theoretical Foundation, Basic Procedures and Software Solution. Available online: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-395173 (accessed on 12 August 2019).

- Mayring, Philipp. 2015. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Grundlagen und Techniken. 12. überarb. Aufl. Weinheim: Beltz. [Google Scholar]

- Misra, Joya, Michelle Budig, and Irene Boeckmann. 2011. Work-family policies and the effects of children on women’s employment hours and wages. Community, Work & Family 14: 139–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, Jessica, and Alison Koslowski. 2019. Making use of work–family balance entitlements: How to support fathers with combining employment and caregiving. Community, Work & Family 22: 111–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, Kimberly J., and Kathrin Zippel. 2003. Paid to Care: The Origins and Effects of Care Leave Policies in Western Europe. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society 10: 49–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, Janice M. 1991. Approaches to qualitative-quantitative methodological triangulation: Methodology Corner. Nursing Research 40: 120–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nandi, Arijit, Mohammad Hajizadeh, Sam Harper, Alissa Koski, Erin C. Strumpf, and Jody Heymann. 2016. Increased Duration of Paid Maternity Leave Lowers Infant Mortality in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Quasi-Experimental Study. PLoS Medicine 13: e1001985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, Ghazala. 2010. Usage of Parental Leave by Fathers in Norway. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 30: 313–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, Benjamin, and Michael Meuser. 2017. Changing Fatherhood? The Significance of Parental Leave for Work Organizations and Couples. In Fathers in Work Organizations: Inequalities and Capabilities, Rationalities and Politics. Edited by Brigitte Liebig and Mechtild Oechsle. Opladen, Berlin and Toronto: Barbara Budrich Publishers, pp. 83–104. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, Margaret. 2009. Fathers, parental leave policies, and infant quality of life: International perspectives and policy impact. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 624: 190–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2017. The Pursuit of Gender Equality. Paris: OECD. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostner, Ilona. 2010. Farewell to the Family as We Know it: Family Policy Change in Germany. German Policy Studies 6: 211–44. [Google Scholar]

- Pedulla, David S., and Sarah Thébaud. 2015. Can We Finish the Revolution? Gender, Work-Family Ideals, and Institutional Constraint. American Sociological Review 80: 116–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfahl, Svenja, and Stefan Reuyß. 2009. Das neue Elterngeld: Erfahrungen und betriebliche Nutzungsbedingungen von Vätern – eine Explorative Studie. Düsseldorf: Hans-Böckler-Stiftung. [Google Scholar]

- Pfahl, Svenja, Stefan Reuyß, Dietmar Hobler, and Sonja Weeber. 2014. Nachhaltige Effelte der Elterngeldnutzung durch Väter. Gleichstellungspolitische Auswirkungen der Inanspruchnahme von Elterngeldmonaten durch erwerbstätige Väter auf betrieblicher und partnerschaftlicher Ebene. Berlin: SowiTra. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer, Jeffrey, and Yinon Cohen. 1984. Determinants of Internal Labor Markets in Organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly 29: 550–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, Rebecca, Janet C. Gornick, and John Schmitt. 2010. Who cares?: Assessing generosity and gender equality in parental leave policy designs in 21 countries. Journal of European Social Policy 20: 196–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rege, Mari, and Ingeborg F. Solli. 2013. The impact of paternity leave on fathers’ future earnings. Demography 50: 2255–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reich, Nora. 2010. Who Cares? Determinants of the Fathers’ Use of Parental Leave in Germany: Working Paper. Hamburg: Hamburg Institute of International Economics. [Google Scholar]

- Reskin, Barbara F., and Debra B. McBrier. 2000. Why Not Ascription? Organizations’ Employment of Male and Female Managers. American Sociological Review 65: 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossin, Maya. 2011. The effects of maternity leave on children’s birth and infant health outcomes in the United States. Journal of Health Economics 30: 221–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudman, Laurie A., and Kris Mescher. 2013. Penalizing Men Who Request a Family Leave: Is Flexibility Stigma a Femininity Stigma? Journal of Social Issues 69: 322–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhm, Christopher J. 2000. Parental leave and child health. Journal of Health Economics 19: 931–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraceno, Chiara, and Wolfgang Keck. 2011. Towards an integrated approach for the analysis of gender equity in policies supporting paid work and care responsibilities. Demographic Research 25: 371–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schober, Pia, and Gundula Zoch. 2019. Change in the gender division of domestic work after mothers or fathers took leave: Exploring alternative explanations. European Societies 21: 158–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoonenboom, Judith, and Burke Johnson. 2017. How to Construct a Mixed Methods Research Design. KZfSS Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 69: 107–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistisches Bundesamt. 2018. Geburtenziffer 2017 Leicht Gesunken: Pressemitteilung Nr.420. Wiesbaden: Statistisches Bundesamt. [Google Scholar]

- Statistisches Bundesamt. 2019. Statistik zum Elterngeld. Beendete Leistungsbezüge für im Jahr 2015 Geborene Kinder: Januar 2015 bis September 2018. Wiesbaden: Statistisches Bundesamt. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, Sakiko. 2005. Parental leave and child health across OECD countries. Economic Journal 115: F7–F28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theunissen, Gert, Marijke Verbruggen, Anneleen Forrier, and Luc Sels. 2009. Career sidestep, wage setback? The impact of different types of employment interruptions on wages. Gender, Work & Organization 18: e110–e131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, Michael, Louise Vinter, and Viv Young. 2005. Dads and Their Babies: Leave Arrangements in the First Year. EOC Working Paper No 37. Manchester: Equal Opportunities Commission. [Google Scholar]

- van Daalen, Geertje, Tineke M. Willemsen, and Karin Sanders. 2006. Reducing work–family conflict through different sources of social support. Journal of Vocational Behavior 69: 462–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandello, Joseph A., Vanessa E. Hettinger, Jennifer K. Bosson, and Jasmine Siddiqi. 2013. When Equal Isn’t Really Equal: The Masculine Dilemma of Seeking Work Flexibility. Journal of Social Issues 69: 303–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinkenburg, Claartje J., Marloes L. Van Engen, Jennifer Coffeng, and Josje S. E. Dikkers. 2012. Bias in Employment Decisions about Mothers and Fathers: The (Dis)Advantages of Sharing Care Responsibilities. Journal of Social Issues 68: 725–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, Ann-Cathrin, and Kerstin Pull. 2010. Warum Väter ihre Erwerbstätigkeit (nicht) unterbrechen. Mikroökonomische versus in der Persönlichkeit des Vaters begründete Determinanten der Inanspruchnahme von Elternzeit durch Väter. German Journal of Human Resource Management: Zeitschrift für Personalforschung 24: 48–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Alemann, Annette, Sandra Beaufaӱs, and Mechtild Oechsle. 2017. Aktive Vaterschaft in Organisationen—Anspruchsbewusstsein und verborgene Regeln in Unternehmenskulturen. Zeitschrift für Familienforschung 29: 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Williams, Joan. 2000. Unbending Gender: Why Family and Work Conflict and What to Do about It. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Joan, Mary Blair-Loy, and Jennifer L. Berdahl. 2013. Cultural Schemas, Social Class, and the Flexibility Stigma. Journal of Social Issues 69: 209–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimbauer, Christine, and Mona Motakef. 2017. Das Paarinterview: Methodologie - Methode - Methodenpraxis. Wiesbaden: Springer VS. [Google Scholar]

- Wotschack, Philip. 2017. Unter welchen Bedingungen bilden Betriebe an- und ungelernte Beschäftigte weiter? Zeitschrift für Soziologie 46: 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | AID:A II stands for “Aufwachsen in Deutschland: Alltagswelten” (Growing up in Germany: Every-Day Worlds); more information on the study can be found at www.dji.de/aida. |

| 2 | It needs to be noted here that highly-educated couples were more likely to participate in the survey and that the weights used in our analyses may not fully account for this potential bias. |

| 3 | Although not typical for Morse’s (1991) notation system of mixed methods designs, we linked the core and supplement with a plus sign and an arrow. Since the data collection occurred in a more or less sequential but independent manner, the plus sign signifies the concurrent collection period of the two data sources. Unlike most mixed methods designs which have a corresponding level of dependency in the data collection and analysis phase, resulting in a “sequential” design as in Schoonenboom and Johnson (2017), we analyzed the two data sources dependently, even though the collection occurred more or less concurrently, thus the additional arrow in the notation. |

| 4 | Parents who had not taken any leave but were planning to take leave in the future were excluded from the analysis as it is not clear whether they realized their plans. |

| 5 | It should be noted here that the fathers who had remained with the same employer since the birth of their youngest child were more likely to take exactly one or two months of leave than the fathers who had changed employers since the birth of their youngest child and the fathers who were self-employed or not employed at the time of interview. Those mothers who remained with the same employer were less likely to take more than twelve months of leave than the mothers who had changed employers or were self-employed or not employed. |

| 6 | The mothers who had only taken the eight-week mandatory maternity leave were defined as not having taken parental leave in this questionnaire and were therefore not asked this question. |

| 7 | We use M/F in front of a quote to indicate whether a statement was made by a mother or father interviewee. The abbreviation PT stands for part-time employed, FT for full-time employed. The contract type of the male partner comes first, the female partner’s second. 12 + 0 PL indicates the division of paid parental leave. The female partner’s length of leave comes first, the male partner’s second. Mothers who took only the eight weeks of mandatory maternity leave were coded as having taken leave for two months. |

| 8 | The exact question wording was: “Turning to your colleagues: If you are absent or have to leave early, do you have colleagues who cover for you or does your work remain undone?” |

| 9 | In an alternative specification (Table A5 in the Appendix A), we included firm size instead of presence of a works council and workplace policies. As formal policies and works councils are concentrated in large firms, we could not include these variables in the same model as firm size. |

| 10 | The perception of an ideal worker norm was operationalized by a scale consisting of the average of four items adapted from Booth and Matthews (2012). For workplace gender norms, we developed a scale consisting of the average of three items based on Gärtner (2012). Supervisor support was measured by creating an average of four items following various studies (Hammer et al. 2009; Harrington et al. 2011; Pfahl et al. 2014). Regarding family-friendly workplace regulation, we generated a scale based on the company case studies by Botsch et al. (2007) consisting of the average of five items. We assessed the level of agreement with each item on a ten-point scale (0 = do not agree at all, 10 = agree completely). Details on our operationalization of the workplace characteristics can be found in the Appendix A in Table A1. |

| 11 | Regarding firm size, an alternative specification shown in Table A5 in the Appendix A reveals that the mothers in small firms (less than 20 employees) are more likely to take short leaves than the mothers in medium-sized firms (20–250 employees). |

| 12 | The same applies to firm size; see Table A6 in the Appendix A. |

| 13 | Also note that the relationship between the prevalence of an ideal worker norm and the mothers’ likelihood to experience negative career consequences was not statistically significant in the alternative specification of the model that includes firm size instead of works council and workplace policies (Table A6 in the Appendix A). |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Samtleben, C.; Bringmann, J.; Bünning, M.; Hipp, L. What Helps and What Hinders? Exploring the Role of Workplace Characteristics for Parental Leave Use and Its Career Consequences. Soc. Sci. 2019, 8, 270. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8100270

Samtleben C, Bringmann J, Bünning M, Hipp L. What Helps and What Hinders? Exploring the Role of Workplace Characteristics for Parental Leave Use and Its Career Consequences. Social Sciences. 2019; 8(10):270. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8100270

Chicago/Turabian StyleSamtleben, Claire, Julia Bringmann, Mareike Bünning, and Lena Hipp. 2019. "What Helps and What Hinders? Exploring the Role of Workplace Characteristics for Parental Leave Use and Its Career Consequences" Social Sciences 8, no. 10: 270. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8100270

APA StyleSamtleben, C., Bringmann, J., Bünning, M., & Hipp, L. (2019). What Helps and What Hinders? Exploring the Role of Workplace Characteristics for Parental Leave Use and Its Career Consequences. Social Sciences, 8(10), 270. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8100270