The Impact of Facebookers’ Posts on Other Users’ Attitudes According to Their Age and Gender: Evidence from Al Ain University of Science and Technology

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Overview

2.2. Advantages of Facebook Use

2.3. Disadvantages of Facebook Use

2.4. The Effect of Gender and/or Age on Facebook Use

3. Research Objectives

- (1)

- To what extent does the gender and age of Facebookers in Al Ain, UAE, have an impact on the type of posts they write and share on Facebook?

- (2)

- What kind of negative attitudes and feelings that negative Facebook posts (i.e., those that provoke negative feelings such as envy) may evoke in Facebookers of different genders and ages in Al Ain, UAE?

4. Methodology

4.1. Participants

4.2. Data Collection

4.2.1. The Questionnaire

4.2.2. The Semi-Structured Interview

4.3. Statistical Analysis

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Results

5.2. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Altakhaineh, Abdel Rahman Mitib, and Hanan Naef Rahrouh. 2015. The use of euphemistic expressions by Arab EFL learners: Evidence from Al Ain University of Science and Technology. International Journal of English Linguistics 5: 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altakhaineh, Abdel Rahman Mitib, and Hanan Naef Rahrouh. 2017. Language Attitudes: Emirati Perspectives on the Emirati Dialect of Arabic According to Age and Gender. The Social Sciences 12: 1434–39. [Google Scholar]

- Altakhaineh, Abdel Rahman Mitib, and Aseel Simak Zibin. 2014. Perception of culturally loaded words by Arab EFL learners. International Journal of Linguistics 6: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkell, Harriet. 2013. Coroner Warns of Dangers of Facebook after Student 19 Targeted by Young Women Bullies Online Hanged Himself. Daily Mail. November 26. Available online: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2513782/Facebook-bullies-led-suicide-student-19-hanged-himself.html (accessed on 24 July 2018).

- Aron, Arthur, Edward Melinat, Elaine N. Aron, Robert Darrin Vallone, and Renee J. Bator. 1997. The experimental generation of interpersonal closeness: A procedure and some preliminary findings. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 23: 363–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, Naomi. 2008. Always on: Language in an Online and Mobile World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, H. Russell. 1988. Research Methods in Cultural Anthropology. Newbury Park: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Bassey, Eno Abasiubong. 2006. The Rise and Fall of ThisDay Newspaper: The Significance of Advertising to Its Demise. Master’s dissertation, School of Journalism and Media Studies, Faculty of Humanities, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, October 31. [Google Scholar]

- Bazarova, Natalya N., Jessie G. Taft, Yoon Hyung Choi, and Dan Cosley. 2012. Managing impression and relationships on facebook: Self presentational and relational concerns revealed through the analysis of language style. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 20: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, Danah M., and Nicole B. Ellison. 2008. Social networking sites: Definition, history and scholarship. Journal of Computer-mediated Communication 13: 210–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caleb, Carr, David Schrock, and Patricia Dauterman. 2009. Speech Act Analysis within Social Network Sites’ Status Messages. Paper presented at 59th International Communication Association Conference, Prague, Czech Republic, May 20; p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Wenhong, and Kye-Hyoung Lee. 2013. Sharing, liking, commenting, and distressed? The pathway between Facebook interaction and psychological distress. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 16: 728–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, Hui-Tzu Grace, and Nicholas Edge. 2012. “They are happier and having better lives than I am”: The impact of using Facebook on perceptions of others’ lives. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 15: 117–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creswell, John W. 2008. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 4th ed. London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Debatin, Bernhard, Jennette P. Lovejoy, Ann-Kathrin Horn, and Brittany N. Hughes. 2009. Facebook and Online Privacy: Attitudes, Behaviors, and Unintended Consequences. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 15: 83–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denscombe, Martyn. 2010. The Good Research Guide: For Small-Scale Social Research Projects, 4th ed. Maidenhead: Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Deters, Fenne große, and Matthias R. Mehl. 2013. Does posting Facebook status updates increase or decrease loneliness? An online social networking experiment. Social Psychological and Personality Science 4: 579–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dey, Ratan, Zubin Jelveh, and Keith Ross. 2012. Facebook Users Have Become Much More Private: A Large-Scale Study. Paper presented at 2012 IEEE International Conference on Pervasive Computing and Communications Workshops, Lugano, Switzerland, March 19–23; Piscataway: IEEE, pp. 346–52. [Google Scholar]

- Duthler, Kirk W. 2006. The politeness of requests made via email and voicemail: Support for the hyperpersonal model. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 11: 500–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, Allen L. 1957. The Social Desirability Variable in Personality Assessment and Research. Ft Worth: Dryden Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison, Nicole B., Charles W Steinfield, and Cliff Lampe. 2007. The benefits of Facebook “friends”: Social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 12: 1143–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elphinston, Rachel A., and Patricia Noller. 2011. Time to face it! Facebook intrusion and the implications for romantic jealousy and relationship satisfaction. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 14: 631–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Facebook. 2017. Fact Sheet. Available online: http://newsroom.fb.com/companyinfo/ (accessed on 26 February 2018).

- Frankfort-Nachmias, Chava, and David Nachmias. 2007. Study Guide for Research Methods in the Social Sciences. London: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Hitchcock, Graham, and David Hughes. 1989. Research and the Teacher: A Qualitative Introduction to School-Based Research. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Holloway, Immy, and Stephanie Wheeler. 2010. Qualitative Research in Nursing and Healthcare, 3rd ed.Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Xiaomeng, Andrew Kim, Nicholas Siwek, and David Wilder. 2017. The Facebook Paradox: Effects of Facebooking on Individuals’ Social Relationships and Psychological Well-Being. Frontiers in Psychology 8: 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalpidou, Maria, Dan Costin, and Jessica Morris. 2011. The relationship between Facebook and the well-being of undergraduate college students. CyberPsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 14: 183–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, Tetsuro, Ikeda Ken’ichi, and Kakuko Miyata. 2006. Social capital online: Collective use of the Internet and reciprocity as lubricants of democracy. Information, Community & Society 9: 582–611. [Google Scholar]

- Krasnova, Hanna, Helena Wenninger, Thomas Widjaja, and Peter Buxmann. 2013. Envy on Facebook: A Hidden Threat to Users’ Life Satisfaction? Paper presented at 11th International Conference on Wirtschaftsinformatik, Leipzig, Germany, February 27–March 1; pp. 1477–91. Available online: https://www.ara.cat/2013/01/28/855594433.pdf?hash=b775840d43f9f93b7a9031449f809c388f342291 (accessed on 24 July 2018).

- Kross, Ethan, Philippe Verduyn, Emre Demiralp, Jiyoung Park, David Seungjae Lee, Natalie Lin, Holly Shablack, John Jonides, and Oscar Ybarra. 2013. Facebook use predicts declines in subjective well-being in young adults. PLoS ONE 8: e69841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Likert, Rensis. 1932. A Technique for the Measurement of Attitudes. Archives of Psychology. New York: The Science Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mazman, S. Güzin, and Yasemin Koçak Usluel. 2011. Gender Differences in Using Social Networks. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology-TOJET 10: 133–39. [Google Scholar]

- Mcandrew, Francis T., and Hye Sun Jeong. 2012. Who Does what on Facebook? Age, Sex, and Relationship Status as Predictors of Facebook Use. Computers in Human Behavior 28: 2359–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehl, Matthias R., Simine Vazire, Shannon E. Holleran, and C. Shelby Clark. 2010. Eavesdropping on happiness: Well-being is related to having less small talk and more substantive conversations. Psychological Science 21: 539–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muise, Amy, Emily Christofides, and Serge Desmarais. 2009. More information than you ever wanted: Does Facebook bring out the green-eyed monster of jealousy? CyberPsychology & Behaviour 12: 441–44. [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Sabater, Carmen. 2012. The linguistics of social networking: A study of writing conventions on facebook. Linguistik Online 56: 111–30. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Richard H., and Sung Hee Kim. 2007. Comprehending envy. Psychological Bulletin 133: 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sotillo, Susana M. 2012. Illocutionary acts and functional orientation of SMS texting in SMS social networks. Aspects of Corpus Linguistics: Compilation, Annotation, Analysis 12: 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Tandoc, Edson C., Patrick Ferrucci, and Margaret Duffy. 2015. Facebook use, envy, and depression among college students: Is facebooking depressing? Computers in Human Behavior 43: 139–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrance, Harry. 2012. Formative assessment at the crossroads: Conformative, deformative and transformative assessment. Oxford Review of Education 38: 323–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trudgill, Peter. 1972. The Social Differentiation of English in Norwich. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela, Sebastián, Namsu Park, and Kerk F. Kee. 2009. Is there social capital in a social network site?: Facebook use and college students’ life satisfaction, trust, and participation. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 14: 875–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Ven, Niels, Marcel Zeelenberg, and Rik Pieters. 2009. Leveling up and down: The experiences of benign and malicious envy. Emotion 9: 419–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1 |

| Gender | Number of Participants (120) |

| Females | 60 |

| Males | 60 |

| Age | Number of Participants (120) |

| Younger (17–45) | 60 |

| Older (46–60+) | 60 |

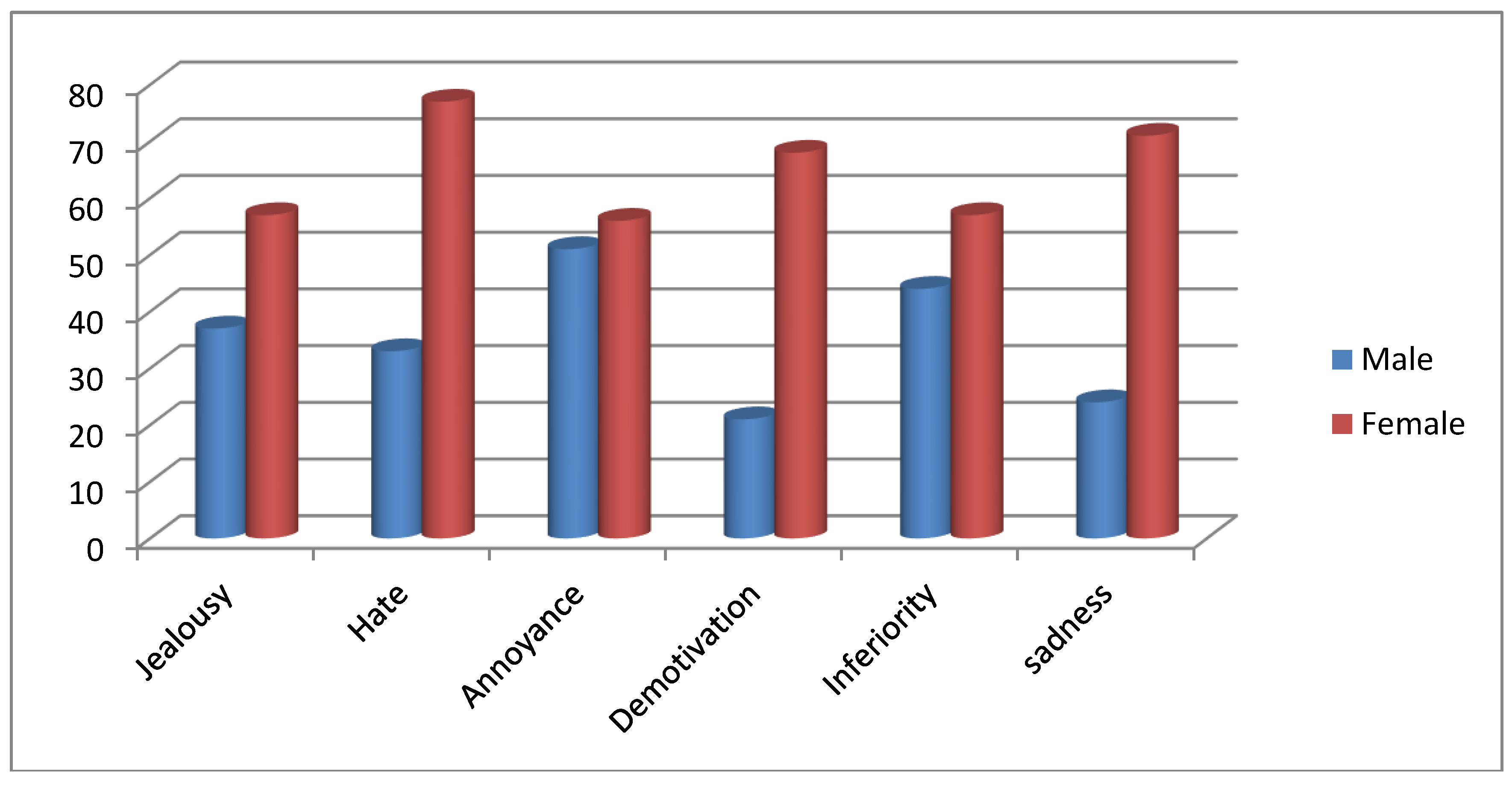

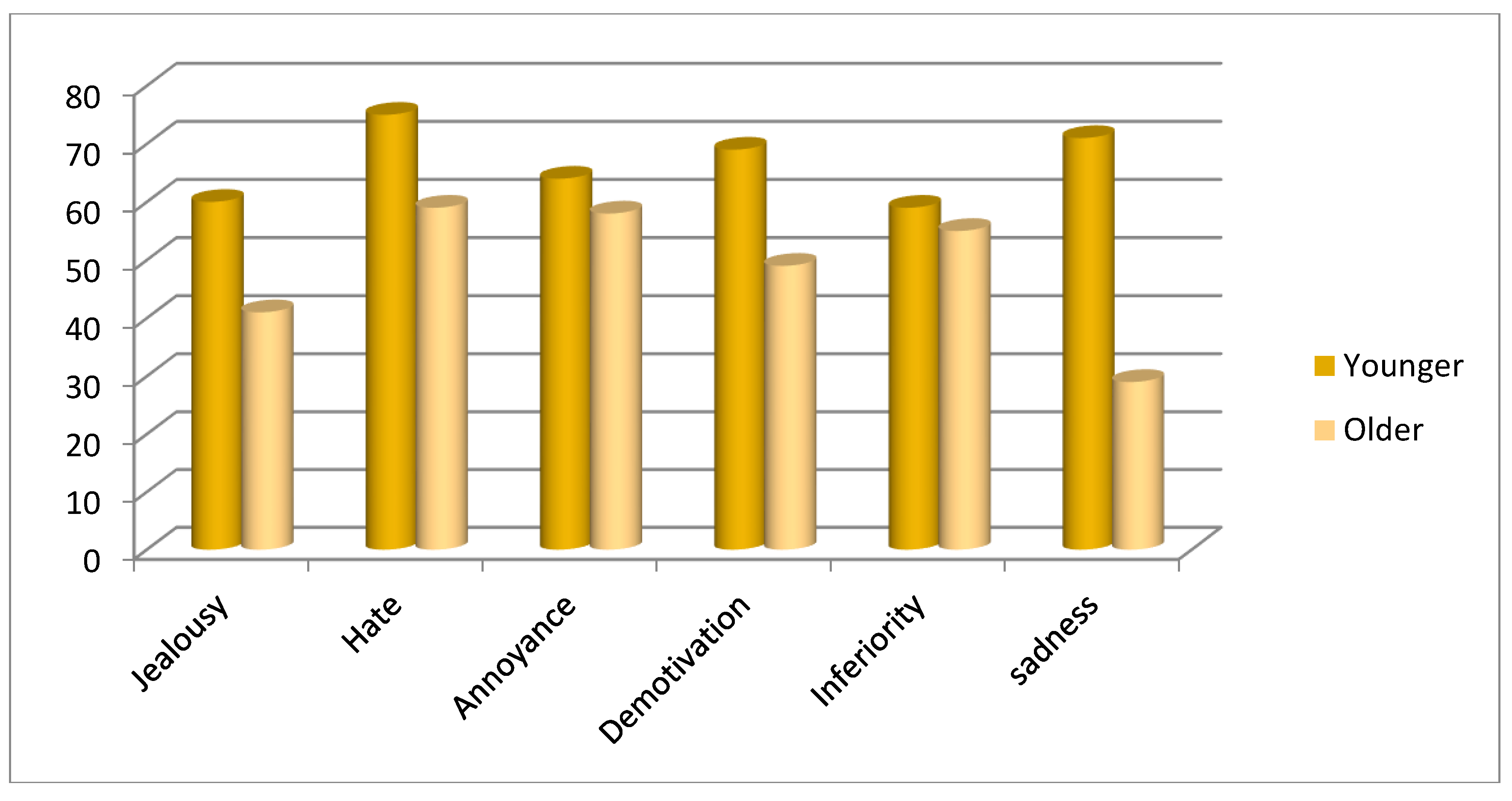

| The Statements | Gender | Age | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females | Males | Younger | Older | |

| 1. I feel envious of the achievements my friends post on Facebook. | 57% | 32% | 55% | 38% |

| 2. Facebook users would post their marital status publicly in order to receive compliments and congratulations. | 79% | 55% | 70% | 48% |

| 3. Posting the graduation certificate on Facebook is pointless. | 55% | 75% | 48% | 77% |

| 4. I would share my photos on Facebook because I like receiving compliments regarding the way I look or the place I am in. | 75% | 58% | 81% | 49% |

| 5. Whenever I go to a famous place, I share it on Facebook using the ‘Check-in’ property as a matter of prestige. | 81% | 55% | 75% | 43% |

| 6. I would share the photo of my new car to tease some friends whom I dislike. | 75% | 70% | 78% | 40% |

| 7. I would share my photo with my girlfriend/boyfriend to tease my ex. | 88% | 68% | 81% | 23% |

| 8. I feel jealous when a friend’s posts on Facebook get more ‘likes’ than my posts. | 57% | 22% | 67% | 21% |

| 9. Some Facebook users would start to hate each other for the different posts they share. | 90% | 30% | 71% | 60% |

| 10. I believe that sharing posts of achievements such as awards or published works is a matter of showing off. | 57% | 88% | 75% | 52% |

| 11. I hate it when people post photos of food on Facebook. | 23% | 78% | 55% | 74% |

| 12. Facebook users are savor receiving ‘likes’ and ‘comments’, so they would frequently share different posts. | 95% | 35% | 91% | 32% |

| 13. Reading a political post that opposes my political view annoys me and makes me hate the person who shared that post. | 63% | 35% | 78% | 57% |

| 14. I would feel envious of my friend who keeps tagging his/her girlfriend/boyfriend in a comment of a romantic post. | 70% | 33% | 71% | 25% |

| 15. I would feel unmotivated when a Facebook friend constantly shares their successful accomplishments on Facebook. | 68% | 21% | 69% | 49% |

| 16. I would feel sad or depressed when a friend keeps sharing sad songs or poems in his/her Facebook. | 71% | 22% | 67% | 30% |

| 17. I would be angry with Facebook friends who tag each other and do not tag me in their posts. | 70% | 25% | 74% | 28% |

| 18. Facebook users would feel inferior because they constantly compare themselves to those who share posts showing how happy they are. | 58% | 25% | 73% | 49% |

| 19. I get mad when a Facebook friend who is not of my religion shares a religious post that opposes my religion. | 78% | 55% | 67% | 51% |

| 20. I hate it when a friend keeps sharing their photos, so I would ignore his/her photos. | 44% | 62% | 48% | 78% |

| Total mean | 68% | 47% | 70% | 46% |

| Group | Mean | Standard Deviation | N | DF | t-Value | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female Facebookers | 68 | 16.82 | 20 | 38 | 3.3536 | 0.0018 |

| Male Facebookers | 47 | 21.55 | 20 | |||

| Younger Facebookers | 70 | 11.08 | 20 | 38 | 5.1251 | 0.0001 |

| Older Facebookers | 46 | 17.26 | 20 |

| Reasons for Sharing Posts | Statements that Indicate the Reasons | Negative Feelings | Statements that Indicate the Feelings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Receiving compliments, likes, and comments | 2, 4, 12 | Jealousy | 1, 8, 14, 20 |

| Sharing updates about personal life | 3, 5, 11 | Hate | 9, 13 |

| Showing off | 5, 10, 20 | Annoyance | 11, 13, 17, 19, 20 |

| Deliberately annoying Facebook friends | 6, 7 | Demotivation | 15 |

| Inferiority | 1, 3, 18 | ||

| Sadness | 16, 17 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Altakhaineh, A.R.M.; Alnamer, S.A.S. The Impact of Facebookers’ Posts on Other Users’ Attitudes According to Their Age and Gender: Evidence from Al Ain University of Science and Technology. Soc. Sci. 2018, 7, 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7080128

Altakhaineh ARM, Alnamer SAS. The Impact of Facebookers’ Posts on Other Users’ Attitudes According to Their Age and Gender: Evidence from Al Ain University of Science and Technology. Social Sciences. 2018; 7(8):128. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7080128

Chicago/Turabian StyleAltakhaineh, Abdel Rahman Mitib, and Sulafah Abdul Salam Alnamer. 2018. "The Impact of Facebookers’ Posts on Other Users’ Attitudes According to Their Age and Gender: Evidence from Al Ain University of Science and Technology" Social Sciences 7, no. 8: 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7080128

APA StyleAltakhaineh, A. R. M., & Alnamer, S. A. S. (2018). The Impact of Facebookers’ Posts on Other Users’ Attitudes According to Their Age and Gender: Evidence from Al Ain University of Science and Technology. Social Sciences, 7(8), 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7080128