1. Introduction

Widening participation in higher education has been at the heart of policies and initiatives which have been designed and implemented in many countries. In European Union (EU) these expansion policies aim at having at least 40% of young people aged 30–34 with a higher education degree by 2020. Some EU countries, such as Ireland, Cyprus, Luxembourg and Lithuania have already met this target (

European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice 2013). In England, there has been a dramatic increase in the number of young people participating in higher education (

Bathmaker et al. 2013;

Alcott 2016). European Union policies do not aim simply at increasing the number of people participating in higher education but on widening access, which means enabling people from all socioeconomic backgrounds to access higher education. In this framework, one of the focal points of higher education policy of the Bologna Process is “to increase the number and diversity of the student population. It should be recalled that the social dimension has been defined as equitable access to and successful completion of higher education by the diversity of populations” (

EACEA/Eurydice 2012, p. 8). Ministers of the European Union have repeatedly decided to assist access to higher education for people from less advantaged backgrounds and under-represented groups by eliminating obstacles to participation (

London Communiqué 2007;

Communiqué of the Conference of European Ministers Responsible for Higher Education 2009).

Despite the increase in the numbers of young people participating in higher education, participation in it is still unequal between social and ethnic groups (

Allen and Storan 2005). Sociologists of education argue that “despite rising attainment levels and a widening of participation, there has therefore been little narrowing of long-standing and sizeable attainment gaps” (

Whitty 2009, p. 268). As a result, in recent years the research focus has shifted from access to higher education to allocation within it, in other words “who goes where?”’ (

Reay et al. 2005, p. 162).

As a result, the issue of the differentiation and stratification within higher education, after policies for the expansion of participation in it which have been implemented in many countries has been an issue of continuing policy and research concern. It is an important issue, as the fact that in most countries institutional differentiation has emerged as a result of expansion (

Duru-Bellat et al. 2008) is related to the issue of providing more opportunities for people from disadvantaged strata and because higher education is “the gatekeeper of managerial and professional positions in the labour market” (

Arum et al. 2007, p. 1). Scholars have argued that differentiation and stratification of higher education constitutes a kind of diversion for people from lower social strata, in a process in which working class people are diverted from opportunities to attend high status institutions and courses of study and are instead channelled into lower level institutions that lead to lower status occupational positions (

Brint and Karabel 1989).

Unequal participation between students from different social groups exists on two interrelated levels. First, there is unequal participation of social groups in higher education institutions. Although there is a mass higher education sector, students from upper- and middle-class families are overrepresented in higher education institutions in relation to their working-class counterparts. For instance, research findings show that minority students tend to be overrepresented in particular fields and non-elite institutions (

Nettles 1988). Research findings indicate that in Scotland students from disadvantaged backgrounds were more likely to attend further education colleges rather than higher education institutions (

Forsyth and Furlong 2000). More recently, in the same country, research has shown that “with the development of mass higher education in Scotland, a stratified system of higher education has emerged in which the traditionally elite institutions continue to have a high percentage of students who are young, middle-class and have high levels of traditional academic qualifications” (

Gallacher 2006, p. 350). Second, even when working class students attend higher education, they are much more likely to attend lower status higher education institutions and departments. Research has shown that more students from less privileged socioeconomic backgrounds attend higher education but their participation in higher education remains unequal in relation to middle class students, since “the more disadvantaged groups have increased their participation mainly in second-tier institutions” (

Croxford and Raffe 2013, p. 173).

Unequal participation in higher education is often attributed to social class differentiated school achievement and performance in university entrance examinations that determine entry to higher education and allocation to the different departments and courses of study. Research has shown that students from less advantaged social groups usually have lower performance at school in relation to upper and middle-class students (

Reay et al. 2005). For instance, there are large social class inequalities in educational achievement in the UK. More specifically, young people with a father with ‘higher professional occupations’ have higher GCSE grades in relation to students with a father with ‘intermediate’ or ‘routine’ occupations (

DCSF 2009;

Hobbs 2016). This means that the latter can only be admitted to institutions and departments with low admissions criteria. In countries such as Greece, in which entry to higher education is determined by performance in nationwide university entrance examinations, working class students are often obliged to choose from a very limited array of choices, since they often have lower performance in these examinations in relation to their middle-class counterparts (

Sianou-Kyrgiou and Tsiplakides 2009). This means that they often do not choose to study in the higher education institution and department of their preference. Instead, they often choose a higher education institution and department according to what is available to them on the basis of their performance in the university entrance examinations (

Sianou-Kyrgiou and Tsiplakides 2011).

In the next part, we draw on Bourdieu and Passeron’s cultural reproduction theory (

Bourdieu and Passeron 1977) to explain class differentials in academic achievement and patterns of participation in higher education. The conceptual tools of this theory have been widely used in research that examines social class differentials in educational trajectories.

2. Theoretical Tools

A growing number of researchers who examine social class differentials in academic achievement and participation in higher education use the theoretical and practical tools developed by Pierre Bourdieu and Jean-Claude Passeron and their cultural reproduction theory in order to explain social inequalities in education and to analyse “how culture and education contribute to social reproduction” (

Lamont and Lareau 1988, p. 153).

Bourdieu was concerned with the role of the educational system in the reproduction of social inequalities, even if it appears to be neutral and meritocratic (

Dimitriadis 2010).

Bourdieu and Passeron (

1977) contended that the school incorporates the cultural dispositions of the upper class and not those of the working class. As a result, students from less advantaged socioeconomic backgrounds “who are not familiar with this kind of socialization will experience school as a hostile environment” (

De Graaf et al. 2000). By contrast, “teachers… communicate more easily with students who participate in elite status cultures, give them more attention and special assistance and perceive them as more intelligent or gifted than students who lack cultural capital” (

DiMaggio 1982, p. 190).

Bourdieu’s theory is expressed by reference to three fundamental concepts, namely, economic, social and cultural capital, habitus and field. According to Bourdieu habitus consists of “schemes of perceptions, thought and action” (

Bourdieu 1989, p. 14). Habitus is a system of dispositions (

Bourdieu 1977a), “an acquired system of generative schemes objectively adjusted to the particular conditions in which it is constituted” (

Bourdieu 1977b, p. 95). These dispositions are durable and transposable (

Bourdieu [1980] 1993). They are durable, which means that they last over time (

Bourdieu [1980] 1993) and transposable “in being capable of becoming active within a wide variety of theatres of social action” (

Maton 2008, p. 51). It should be noted that Bourdieu does not believe that the actions and practices of individuals are the result of habitus alone. Rather, he claims that practices are the result of the relationship between habitus and a field (

Bourdieu [1980] 1993). Cultural capital, in its three forms, that is, the embodied state, the objectified state and the institutionalized state, entails familiarity with the dominant culture in a society (

Bourdieu 1986). Since success at school presupposes familiarity with the dominant culture and possession of cultural capital, students from lower socioeconomic background lack cultural capital and familiarity with the dominant culture, so they usually have lower performance (

Katsillis and Rubinson 1990). In relation to social capital, Bourdieu contends that it is “the aggregate of the actual or potential resources which are linked to possession of a durable network of more or less institutionalized relationships of mutual acquaintance and recognition or in other words, to membership in a group-which provides each of its members with the backing of the collectively-owned capital, a ‘credential’ which entitles them to credit, in the various senses of the word” (

Bourdieu 1986, p. 251). At a practical level this means that parents with high levels of social capital can mobilize these networks to gain access to valuable information about the education system. Finally, economic capital refers to an individual’s income and wealth and it plays “an important role in the process of educational attainment” (

De Graaf 2007, p. 383). For instance, well off families can provide their offspring with costly private tuition to help them achieve high marks and to prepare them for preparation in university entrance examinations.

Mobilization of these capitals is essential in higher education. Research employing Bourdieu’s conceptual tools has shown that the privileged middle classes can mobilise their capitals and gain advantage in the transition from higher education to the labour market, since, having a ‘feel for the game’ they had “internalized the logic of the game and played accordingly” (

Bathmaker et al. 2013, p. 740).

3. The Research Study

The above discussion led us to pose the following research question: Are students with parents with lower education level underrepresented in high status university departments in Greece?

In other words, we wanted to examine whether the widening of participation in higher education has led to more students from less privileged socioeconomic backgrounds attending prestigious courses of study. In Greece, the widening of participation in higher education means that the number of students attending higher education has increased sharply in the last two decades (

Sianou-Kyrgiou and Tsiplakides 2009). More specifically, from 45,000 entrants in 1995, for the academic year 2017–2018 there were slightly more than 70,000 entrants. The research hypothesis was that students from less privileged socioeconomic backgrounds usually study in lower status university departments.

If research findings show that there are great differentials concerning distribution in the different university departments, this means that the higher education sector is stratified in Greece. This issue is important, since a stratified by socioeconomic background higher education sector means that the increased participation in higher education has been accompanied by stratification within it, which contributes to the persistence of social inequalities. At a time of crisis facing Greece it is even more important than before to study the impact of socioeconomic background in life chances, since young people from less privileged socioeconomic backgrounds are in danger of being unemployed and becoming marginalized.

Data was obtained from an official source, the Hellenic Statistical Authority which collects data from all first-year students who enter higher education. A questionnaire is administered to all first-year student who complete it upon registration.

We decided to focus on two regional higher education institutions, the University of Crete and the University of Patras. Our decision was determined by the fact that research usually focuses on the two biggest universities, the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens and the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, often ignoring the regional higher educational institutions. Thus, we intend to fill a research gap and provide researchers and policy makers with interesting and useful data.

It is also worth noting a limitation of the research. The fact that it employs only quantitative research methods, while qualitative research, which emphasizes “the meaning that key players attach to various acts” (

Pugsley 2004, p. 8) has not been employed, means that care should be taken in generalizing the research findings.

4. Research Findings

We obtained interesting data concerning the social class composition of the different university departments in these two institutions. As we have mentioned, we chose to examine statistical data from two regional higher education institutions: The University of Crete and the University of Patras.

From the University of Crete, we decided to examine the Medical School, the Department of Primary School Education, the Department of Computer Science and the Department of Philosophical and Social Studies. The Medical School has more demanding admission criteria, which means that students wishing to attend it need to have high performance in the university entrance examinations. These examinations are held nationwide at the end of the school year and determine access to and allocation in the different higher education institutions and departments. The Department of Primary School Education and the Department of Philosophical and Social Studies have lower admissions criteria, recruiting applicants with lower performance in the university entrance examinations. In relation to admissions criteria, for the academic year 2014–2015, students who wished to attend the Medical School needed to obtain a minimum of 18,786 point out of a maximum of 20,000 points, which is a high-performance level. The high performance required for entry to the Medical School is attributed that it is a highly sought-after course of study and many students wish to attend it. However, due to the limited number of places available, due to a “numerus clausus” policy, (

Gouvias 1998), only applicants with the highest performance can secure a place in it. Similarly, students who wish to attend the Department of Primary School Education need a minimum of 14,146 points, while applicants who wish to attend the Department of Computer Science and the Department of Philosophical and Social Studies needed 13,270 and 12,846 points respectively. It is worth mentioning that in Greece admission to higher education institutions depends on (a) achievement in the nationwide university entrance examinations held at the end of each school year, (b) applicants’ preference for the different higher education institutions, Schools and departments and (c) the number of places available in each department.

From the University of Patras, we examined the Pharmaceutical Department, the Department of Civil Engineers, the Department of Theatrical Studies and the Department of Preschool Education. The first two departments have more demanding admission criteria, so applicants wishing to attend them need to have high performance in the university entrance examinations. By contrast, the Department of Theatrical Studies and the Department of Preschool Education have less demanding admission criteria, so applicants with lower performance can attend them. In particular, for the academic year 2014–2015, the minimum number of points for entry to the Pharmaceutical Department was 18,265 points, for the Department of Civil Engineers 16,497 points, for the Department of Theatrical Studies 11,659 points and for the Department of Preschool Education 13,650 points.

We then present the composition of these university departments by father’s education level for the students who first enrolled in these departments in the academic year 2014–2015 (

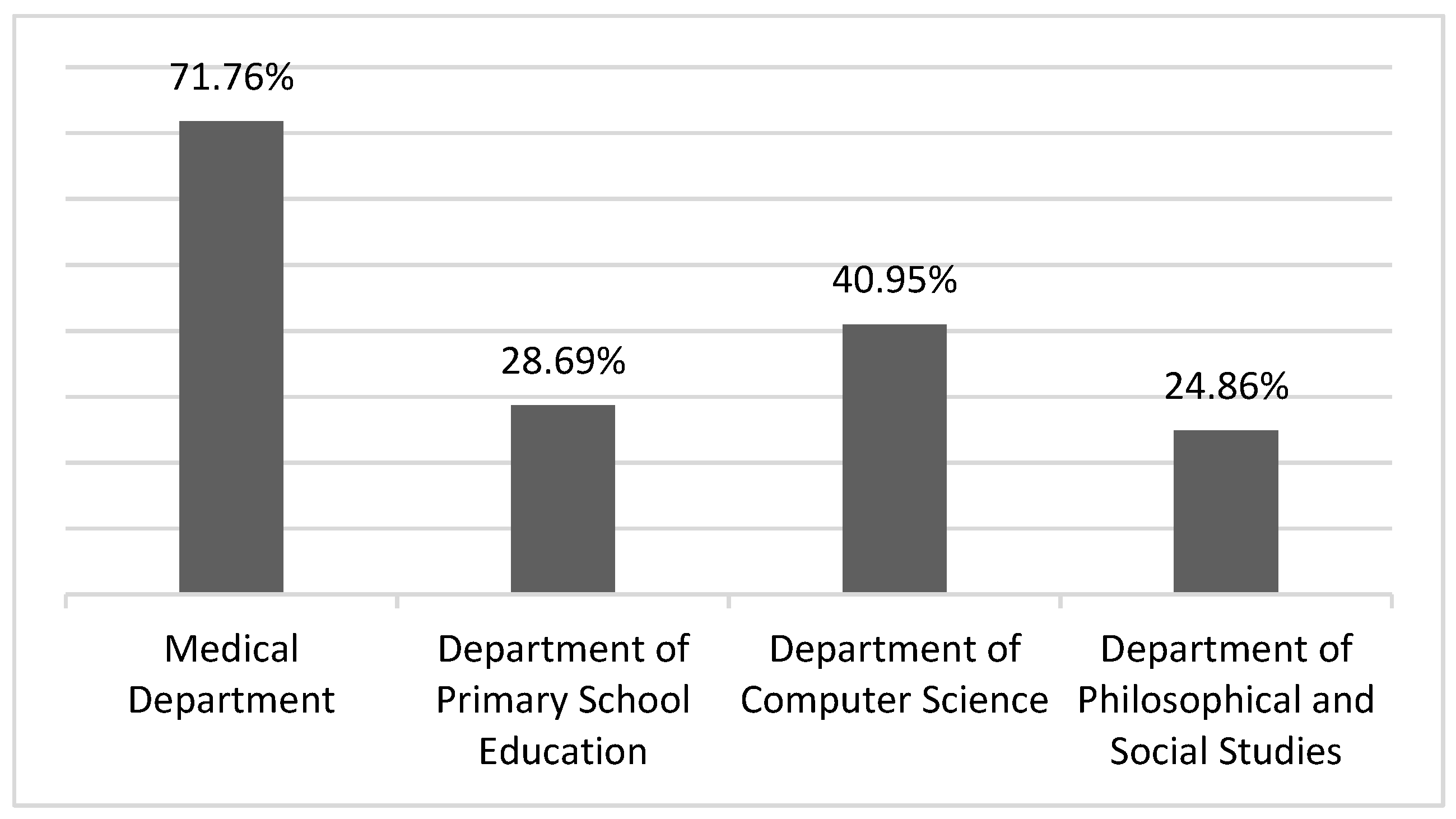

Figure 1).

We then present the composition of these university departments by mother’s education level for the students who first enrolled in these departments in the academic year 2014–2015 (

Figure 2).

The above data indicate that these university departments are stratified by the level of parental education. More specifically, students with parents who have participated in higher education are overrepresented in the Medical School and the Department of Computer Science which have higher admissions criteria than the Department of Primary School Education and the Department of Philosophical and Social Studies. For instance, as

Figure 1 shows, 66.24% of the students who attend the Medical School and the 38.82% of Students in the department of Computer Science have a father with the highest education levels. On the basis of these data we argue that familial cultural capital is at work here (

Bourdieu 1977a). Students from privileged social classes have preferences for particular fields of study that lead to privileged occupational trajectories because the rich cultural capital of their families has allowed them to develop such expectations. By contrast, only 25.69% of the students who attend the Department of Primary School Education and the 19.67% of the students in the Department of Philosophical and Social Studies have a father with the highest education levels. Similarly, as

Figure 2 shows, 71.76% of the students who attend the Medical School and 40.95% of the students in the department of Computer Science have a mother with the highest education levels. By contrast, only 28.69% of the students who attend the Department of Primary School Education and the 19.67% of the students in the Department of Philosophical and Social Studies have a mother with the highest education levels.

In summary, we see that the students who attend the Medical School and the Department of Computer Science have higher performance in the university entrance examinations, so they choose to study in these prestigious departments who lead to occupational trajectories with increased material and symbolic benefits. Students with parents with lower education level are overrepresented in the Department of Primary School Education and the Department of Philosophical and Social Studies. Their lower performance in the university entrance examinations means that they can only choose departments available to them on the basis of their performance and not necessarily on the basis of their preferences.

Having presented the findings in relation to the University of Crete, we then present the composition of these university departments by father’s education level for the students who first enrolled in these departments in the University of Patras in the academic year 2014–2015 (

Figure 3).

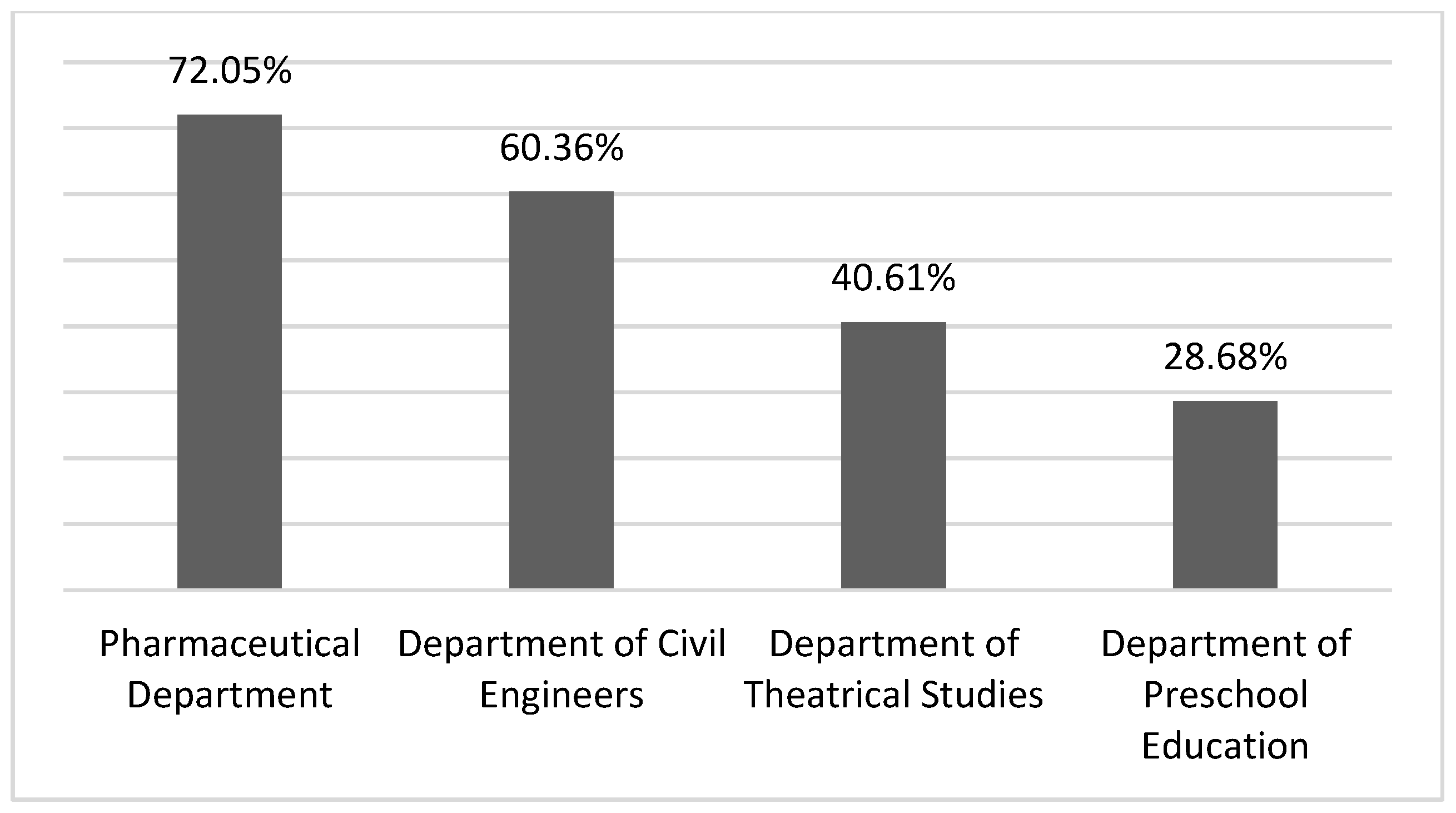

In the next figure, we present the composition of by mother’s education level for the students who first enrolled in the University of Patras in the academic year 2014–2015 (

Figure 4).

The above data confirm the research findings from the University of Crete and show that these university departments in the University of Patras are also stratified by socioeconomic background. More specifically, students with a parent who has higher education levels (e.g., have participated in higher education and/or have attended postgraduate studies) are overrepresented in the Pharmaceutical Department and the Department of Civil Engineers. For instance, as

Figure 3 shows, 67.59% of the students who attend the Pharmaceutical Department and the 66.28% of the students in the Department of Civil Engineers have a father with the highest education levels. By contrast, only 32.28% of the students who attend the Department of Theatrical Studies and the 19.67% of the students in the Department of Preschool Education have a father with the highest education levels. Similarly, in relation to the education level of the mother, as

Figure 4 shows, 72.05% of the students who attend the Pharmaceutical Department and the 60.36% of the students in the Department of Civil Engineers have a mother with the highest education levels. By contrast, only 40.61% of the students who attend the Department of Theatrical Studies and the 28.68% of the students in the Department of Preschool Education have a mother with the highest education levels.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The first conclusion we draw from the research findings we presented above is that widened access to higher education in recent years means that students from less advantaged backgrounds have opportunities for participation in higher education. This, in turn, means that they can benefit from participation in it. It is undeniable that this constitutes a positive step toward the narrowing of social inequalities in higher education.

However, as we have seen, equality of opportunity is not only about entering higher education but is also dependent on allocation within the different institutions and departments. If we look at allocation within the different institutions and departments a different picture emerges. In accordance with research in other countries we also found that “students from more advantaged social backgrounds tend to be concentrated in higher-status institutions… as education expands, inequalities in total participation at a given stage, such as HE, are replaced by inequalities in the distribution across types of education within that stage” (

Raffe and Croxford 2015, p. 316). The research data we present in this paper confirm findings that show that, despite widened higher education access, disadvantaged groups are still underrepresented in higher status institutions that usually guarantee successful occupational trajectories and higher returns in the labour market (

Boliver 2013;

Croxford and Raffe 2015).

More specifically, the research question we posed was whether students from less privileged socioeconomic backgrounds are underrepresented in high status university departments. The research findings we presented in this paper show that these students are overrepresented in lower status university departments, confirming research findings that indicate that students from less advantaged backgrounds usually study in lower-status institutions (

Arum et al. 2007;

Iannelli et al. 2011). It is also worth noting that in research designed to examine the success rates in higher education of whether applicants from different social or ethnic backgrounds in the four countries of the UK (years 1996–2010), researchers found that “in each cohort and in each home country, success rates were higher among applicants from professional- and managerial-class backgrounds than intermediate- or working-class backgrounds and they were nearly always higher among white applicants than those from visible ethnic minorities” (

Croxford and Raffe 2014, p. 87).

The findings we present show that the university department students choose is correlated with parental education level. These findings also show that the higher education sector in Greece is highly stratified. We may have increased participation but students from different socioeconomic strata gain access to different higher education departments. We argue that performance in university entrance examinations, which is correlated with socioeconomic background, explains the greater part of this difference. Students from lower social strata cannot study in high status university departments but they are not able to do so, on the basis of their performance in these examinations that determine access to and distribution within higher education institutions and courses of study.

The above findings provide strong evidence that, contrary to the official rhetoric, widened participation in higher education, does not automatically entail equality of opportunity, as it is clear that familial financial, cultural and social capital impact strongly on the choice making process. If the expansion of the higher education sector is followed by differentiation within it, it can lead, as the research data we have presented show, to the persistence of current forms of privilege for some social classes (

Brown and Hesketh 2004).

Drawing on Bourdieu, we argue that familial cultural and social capital and habitus impact on the choice process. As we have seen, most students in the high status higher education departments have a parent who has experience from participation in higher education. These families know, consequently, how to “play the game,” so they can make choices based on information of the education system (

Bourdieu 1986). The habitus of upper and middle-class students equips them with specific as regards their education and the transition to the labour market (

Bourdieu 1977a). These students do not simply with to attend higher education but the highest parts within it, according to their preferences and the benefits in the labour market, in accordance to what is acceptable ‘for people like us’ (

Bourdieu 1990, p. 64–65). For these students, a lower status institution or course of study is not part of a ‘normal biography’ (

Du Bois-Reymond 1998) but is part of a ‘normal biography’ for working class students. However, we believe that qualitative research with the use of semi-structured interviews is necessary to uncover the impact of familial cultural, social and economic capital.

On the basis of the aforementioned research findings, we argue that measures should be taken to assist students from disadvantaged backgrounds to fulfil their potential and participate equally in higher education and not only in its less prestigious institutions and departments. This is important, as according to official documents, although measures to help specific groups based on socio-economic status, gender, disability or migrant status exist in many countries, they do not form a central element of higher education policy (

EACEA/Eurydice 2011). This also means that to make participation in higher education equitable for young people across the social spectrum, the wider social inequalities need to be tackled, since it is difficult “for education to equalise relative life-chances because it cannot compensate for wider social inequalities” (

Brown 2013, p. 693).

In conclusion, initiatives and policies that set as their target the reduction of social inequalities in higher education should not simply address the issue of access to higher education, since after policies for the widening of participation in higher education, young people from all social strata participate in it. Rather, educational policy needs to focus on reducing the impact of the internal differentiation and stratification of higher education and provide working class students with equal opportunities to attend higher status institutions and courses of study. Educational policy also needs to focus on reducing the achievement gap in educational attainment in secondary education, as it appears to impact strongly on performance in university entrance examinations and consequently on the higher education choice making process.