Mining Corporations, Democratic Meddling, and Environmental Justice in South Africa

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Macro-Economic Policy, Governance and the Power of Mining Corporations

1.2. Corruption and Corporate Influence on Democracy and State Decision-Making

1.3. Mining Companies Influencing Local Community Cohesion against Mining Impacts

1.4. Democracy and Political Settlement Epistemologies

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Political Connections and Corruption between Mining Companies and Government

“ … he’s [mining applicant] is connected with somebody within the government or within the DMR, I can promise you … So if they [government] now start saying no, no, no, no Steenskampsburg is out I’m not going to allow you to do it [mine], they going to be pissing off somebody [mining connection] … We were at the cuff of having such a meeting in 2008 [to proclaim a protected area] … where agriculture, ourselves, Environmental Affairs, Water Affairs, DMR, labour, Premier’s office, everybody would sit around the table and draw up these maps and identify priority areas and it was cancelled two days before. There is no political will to do it … they all said we agree with you 100% but if you implement it I will be without a job”

“She [mining applicant] applied for that farm [for coal mining] … but … there were I think something like 11 inconsistencies … I objected on all of it … The applicant … [had] high standing in the politics and her husband was a mining engineer. I didn’t know that … he [DMR regional manager] was fighting me so that they [could] … override my objection … She [applicant] said … the people here, in this [DMR] office … assisted her with her application … They all work together … to get prospecting and mining rights … If you do an application you must have an independent consultant.”

“The reason we used him [environmental consultant] is because … he wrote most of the rules of water for Water Affairs … they [government] consult with him …”

“… Mining companies are employing these guys [from national government] to help them further—they offer them twice the salary … and once he is employed by mining he knows the process. You get your license … so much easier.”

“… the local politicians they in on the act too … deals are done so almost certainly the … miners … have certain important political partners—that’s what you do … [Government’s excuse for allowing mining is that] we create jobs …”

3.2. Mining Companies Exploiting Vulnerable Communities to Spearhead Mining Development

“… The mining companies are very clever … most of them are … overseas companies that have been developed for over many years, so they have got a very clever strategy … So when they come to a community like this [Dullstroom township] it is so easy for them to exploit the innocence … people are not very knowledgeable about what the end results are and what it actually all entails. So they [mining corporations] can easily exploit places in Africa … I have seen it in my job that they do a lot of window dressing, fantastic promises and lovely plans, but when it comes to implementation they get away with murder ...”

“Currently with the economics in South Africa … a lot of people are unemployed, but then they don’t think about things like aesthetical values and sense of place, they think about survival, so for those guys if you offer them jobs [to] mine here in the middle of Dullstroom they will take it … some of them have got families that are starving, so we can understand that but unfortunately the mining companies abuses that situation for their own [benefits]”

“[Pro-miner X—a Dullstroom farmer conducting mining on his property] was talking to the [township] people [about] job creation [and] they must go and have a strike in town … and they can make millions out of this … they [township residents] wanted to close the whole town ...”

“… We had a stakeholder workshop where we wanted to present the intent to proclaim this area [Wakkerstoom, a protected area] … There were like 2000 or 5000 people who were bussed by mining [from the township] … They were protesting against our intent to proclaim it as a nature reserve … They [township residents] kicked chairs, they fought … they spoke about a figure of like 5000 [mining jobs] … I think shipped them by bus [by the mining company] … it’s a dirty game actually that is being played … there is a politically well-connected member of this mining team. He actually went to go see the communities and I don’t know if he paid for it or how it happened but he later when we were sitting around a table admitted that he may have spoken to the community …”

“… the mining issue was an induced issue that was from a mining company that wanted to open pits at the back here [in Dullstroom] … they go into a township and buy off some of the councillors in the area and get a hundred people together and they start organising marches and those things. But it is money flowing in for persons, I mean they’re virtually bought … in Chrissiesmeer … there was a public meeting … in came 300 or 400 locals, placards waving … my name was on those signs and [they were saying] we don’t want greed and [interviewee X] … so I got up and walked between the middle of them and said whose this [interviewee X] … they have no idea and they were talking to me, so they were obviously bought … But when you unemployed and you don’t have much of a hope of being employed in the future. If someone comes around and says you know we will give you employment but you must get rid of … these guys who are giving us a hassle … So it is very easy for a mining company to go and buy a little bit of influence in the township”

“… there are people [traditional leaders] who are supporting the mine though they are not doing it openly … they [mining company] used to go to those individuals especially stakeholders [the traditional council] … who are connected to the mine … They [traditional council] are on the mine’s side … not on the side of the community …”

“… it happens in all of these places where the traditional leaders end up being bribed quite substantially by the mining companies. It’s quite cleverly done such that suddenly they are all driving new cars … so it’s not in the form of hard cash … they are benefiting to be on the side of the mine so the whole community is anti the mine …”

“Our ward councillor is on the side of the mine. His son has already been taken [by the mine] and they trained him in a couple of courses. So already, if the mine starts he is going to have a position in that company. So it was easy for him [ward councillor] to push for the mine to start because he will get something on his side ...”

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aulby, Hannah. 2017. Undermining Our Democracy. The Australian Research Institute. Available online: http://www.tai.org.au/sites/default/files/P307%20Foreign%20influence%20on%20Australian%20mining_0.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2017).

- Beck, Ulrich. 1992. Risk Society. London, Thousand Oaks and New Delhi: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Behuria, Pritish, Buur Lars, and Gray Hazel. 2017. Studying political settlements in Africa. African Affairs 116: 508–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand South Africa. 2018. SA’s Key Economic Sectors. Available online: https://www.brandsouthafrica.com/investments-immigration/business/investing/economic-sectors-agricultural (accessed on 22 November 2018).

- Caripis, Lisa. 2017. Combatting Corruption in Mining Approvals. A Report Prepared for Transparency International, Australia. Available online: file:///C:/Users/llewel/Downloads/2017_CombattingCorruptionInMiningApprovals_EN.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2018).

- Castells, Manuel. 2000. Materials for an exploratory theory of the network society. British Journal of Sociology 51: 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanagh, John, and Jerry Mander. 2004. Alternative Economic Globalisation: A Better World Is Possible, 2nd ed. Report of the International Forum on Globalisation. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Environmental Rights. 2015. Full Disclosure. Available online: https://fulldisclosure.cer.org.za/2015/download/CER-Full-Disclosure.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2018).

- Centre for Environmental Rights. 2016. Full Disclosure. Available online: https://fulldisclosure.cer.org.za/ (accessed on 2 July 2018).

- Cohen, Jean, and Andrew Arato. 1992. Civil Society and Political Society. Cambridge: Cambridge MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Tracey. 2013. Miners Thumb Noses at Ecosystems. Business Day, November 22. [Google Scholar]

- Desai, Deval, and Michael Woolcock. 2012. The Politics of Rule of Law Systems in Developmental States: ‘Political Settlements’ as a Basis for Promoting Effective Justice Institutions for Marginalized Groups. ESID Working paper No. 8. University of Manchester. Available online: http://www.effective-states.org/wp-content/uploads/working_papers/final-pdfs/esid_wp_08_desai-woolcock.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2018).

- Di John, Jonathan, and James Putzel. 2009. Political Settlements: Issues Paper. Governance and Social Development Resource Centre, University of Birmingham. Available online: http://epapers.bham.ac.uk/645/1/EIRS7.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2018).

- Eastern Cape Socio-Economic Consultative Council. 2011. Municipalities and Communities in Mining Initiatives. Working paper Series, No 15. Available online: https://www.ecsecc.org/documentrepository/informationcentre/WP15_1.pdf (accessed on 5 July 2018).

- Fig, David. 2005. Manufacturing amnesia. International Affairs 81: 599–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlong, Aashleigh. 2017. Northern Cape families resist mining company’s efforts to move them. News24, January 30. [Google Scholar]

- Gould, Kenneth, Pellow David, and Schnaiberg Allan. 2004. Interrogating the Treadmill of Production. Journal of Organization and Environment 17: 296–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenstein, Ran. 2003. Civil Society, Social Movements and Power in South Africa. Centre for Civil Society and School of Development Studies Research Report, Durban. Available online: http://ccs.ukzn.ac.za/files/Greenstein.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2018).

- groundWork. 2003. National Report on Community-Based Air Pollution Monitoring in South Africa: Air Pollution in Selected Industrial Areas in South Africa, 2000–2002. Pietermaritzburg: groundWork. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson, Maria-Therese. 2017. Private Politics and Peasant Mobilization. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallowes, David, and Mark Butler. 2002. Corporate accountability in South Africa. groundWork Report 2002. Pietermaritzburg: groundWork. [Google Scholar]

- Hallowes, David, and Victor Munnik. 2006. Poisoned Spaces. groundWork Report 2006. Pietermaritzburg: groundWork. [Google Scholar]

- Hay, William. 2005. What is democracy? Liberal Institutions and Stability in Changing Societies. Orbis 50: 133–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickey, Sam. 2013. Thinking about the Politics of Inclusive Development: Towards a Relational Approach. ESID Working paper No. 1. University of Manchester. Available online: http://www.effective-states.org/wp-content/uploads/working_papers/final-pdfs/esid_wp_01_hickey.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2018).

- Hill, Nicholas, and Warren Maroun. 2015. Assessing the potential impact of the Marikana incident on South African mining companies. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences 18: 586–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Human Rights Watch. 2011. Papua New Guinea: Serious Abuses at Barrick Gold Mine. Available online: https://www.globalpolicy.org/the-dark-side-of-natural-resources-st/minerals-in-conflict/49778.html?itemid=893 (accessed on 26 November 2017).

- Industrial Development Corporation. 2016. Resource Document. Available online: https://www.idc.co.za/about-the-idc/board-of-directors.html (accessed on 5 July 2018).

- Keane, John. 1998. Civil Society, Old Images, New Visions. Cambridge: Blackwell Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Kelsall, Tim. 2016. Thinking and Working with Political Settlements. Overseas Development Institute Briefing. Available online: https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/10185.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2018).

- Knutsen, Carl, Kotsadam Andreas, Olsen Eivind, and Wig Tore. 2017. Mining and local corruption in Africa. American Journal of Political Science 61: 320–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, Llewellyn. 2009. Civil Society Reflexiveness in an Industrial Risk Society. Ph.D. dissertation, Kings College London, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard, Llewellyn. 2012. Civil society leadership and industrial risks. Journal of Asian and African Studies 46: 113–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, Llewellyn. 2014. Characterising civil society and its challenges in post-Apartheid South Africa. Journal of Social Dynamics 40: 371–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, Llewellyn. 2017a. State Governance, Participation and Mining Development. Politikon 44: 327–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, Llewellyn. 2017b. Environmental Impact Assessments and public participation. Environmental Assessment Policy and Management 19: 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard, Llewellyn, and Themba Lebogang. 2018. Exploring the Impacts of Mining on Tourism Growth and Local Sustainability. Sustainable Development 26: 206–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, Brian, Alan Hirsch, and Woolard Ingrid. 2015. Governance and Inequality: Benchmarking and Interpreting South Africa’s Evolving Political Settlement, Effective States and Inclusive Development (ESID). Working paper No. 51. University of Manchester. Available online: http://www.effective-states.org/wp-content/uploads/working_papers/final-pdfs/esid_wp_51_levy_hirsch_woolard.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2018).

- Lopez, Aldo, and Thomas McDonagh. 2017. The Anti-Mining Struggle in El Salvador. The Democracy Centre. Available online: https://democracyctr.org/resource/the-anti-mining-struggle-in-el-salvador-corporate-strategies-and-community-resistance/ (accessed on 28 November 2017).

- Mabuza, Linda, N. Msezane, and M. Kwata. 2010. Mining and Corporate Social Responsibility Partnerships in South Africa. Pretoria: Africa Institute of South Africa, Policy Brief no. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Madihlaba, Thabo. 2002. The Fox in the Henhouse. In Environmental Justice in South Africa. Edited by David McDonald. Athens: Ohio University Press, Cape Town: University of Cape Town Press, pp. 156–67. [Google Scholar]

- Malherbe, Stephan, and Nick Segal. 2001. Corporate governance in South Africa. Paper presented at Policy Dialogue Meeting on Corporate Governance in Developing Countries and Emerging Economies, OECD Development Centre and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, Paris, April 23–24. [Google Scholar]

- Marinovich, Greg. 2016. Murder at Small Koppies: The Real Story of the Marikana Massarce. Cape Town: Zebra Press. [Google Scholar]

- Matten, Dirk. 2004. The impact of the risk society thesis on the environmental politics and management in a globalizing economy—Principles, proficiency, perspectives. Journal of Risk Research 7: 377–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menocal, Alina. 2015. Inclusive Political Settlements: Evidence, Gaps, and Challengers of Institutional Transformation, Governance and Social Development Resource Centre, University of Birmingham. Available online: http://publications.dlprog.org/ARM_PoliticalSettlements.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2018).

- Mine Web. 2011. South African Police Squad Raids Minerals Department in Corruption Investigation. Available online: http://www.mineweb.co.za/mineweb/content/en/mineweb-politicaleconomy?oid=132453andsn=Detail (accessed on 23 October 2014).

- Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Act. 2002. Available online: http://cer.org.za/virtual-library/legislation/national/mining/mineral-and-petroleum-resourcesdevelopment-act-2002 (accessed on 12 May 2015).

- Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Amendment Act. 2008. Available online: https://www.environment.gov.za/sites/default/files/legislations/mineralandpetroleum_resourcesdevelopment49of2008_gn32151.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2018).

- Monshipouri, Mahmood, Welch Claude, and Kennedy Evan. 2003. Multinational Corporations and the Ethics of Global Responsibility. Human Rights Quarterly 25: 965–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mzwakali, Sobantu. 2017. Mining in South Africa: Radical Resistance. Available online: https://www.opendemocracy.net/sobantu-mzwakali/mining-in-south-africa-radical-resistance (accessed on 26 November 2017).

- Naidoo, Kumi. 2003. Civil Society, Governance and Globalisation; Paper presented at the World Bank headquarters in Washington, DC, February 10. Available online: http://www.civicus.org/new/media/WorldBankSpeech.doc (accessed on 12 April 2006).

- Nasstrom, Sofia. 2006. Representative Democracy as Tautology. European Journal of Political Theory 5: 321–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Waste Management Strategy. 1998. Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism, Republic of South Africa. Available online: http://www.polity.org.za/pol/acts/ (accessed on 9 September 2014).

- Neocosmos, Michael. 2011. Transition, Human Rights and Violence. Interface 3: 359–99. [Google Scholar]

- Ntongana, Thembela. 2018. Family of Murdered Xolobeni Activists Appeal to NPA to Unblock Investigation. Mail and Guardian. March 28. Available online: https://mg.co.za/article/2018-03-28-family-of-murdered-xolobeni-activist-appeal-to-npa-to-unblock-investigation (accessed on 13 July 2018).

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. 2014. Phase 3 Report on Implementing the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention in South Africa. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/daf/anti-bribery/SouthAfricaPhase3ReportEN.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2014).

- Parliamentary Report. 2005. Announcements, Tabling’s and Committee Reports; Republic of South Africa, Number 106, Second Session, Third Parliament; September 15. Available online: www.parliament.gov.za (accessed on 25 March 2013).

- Pellow, David. 2006. Social Inequalities and Environmental Conflict. Horizontes Antropológicos 12: 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillay, Devan. 2007. The Stunted Growth of South Africa’s Developmental State Discourse. Africanus 37: 198–215. [Google Scholar]

- Post, Robert. 2006. Democracy and Equality. The Annuals of American Academy of Political and Social Science 603: 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogerson, Christian. 2011. Mining Enterprise, Regulatory Frameworks and Local Economic Development in South Africa. African Journal of Business Management 5: 13373–82. [Google Scholar]

- Scholte, Jan Aart. 2001. Civil Society and Democracy in Global Governance. Coventry, UK: Centre for the Study of Globalisation and Reconciliation, Economic and Social Research Council, University of Warwick. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Warwick. 2014. Political donations corrupt democracy in ways you might not realize. The Guardian, September 11. [Google Scholar]

- South African Constitution. 1996. Republic of South Africa, Act 108 of 1996. Available online: http://www.polity.org.za/pol/acts/ (accessed on 14 May 2015).

- Spicer, Michael. 2016. Government and business—Where did it all go wrong? Rand Daily Mail, November 15. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics South Africa. 2018. Quarterly Labour Force Survey. Available online: file:///C:/Users/llewel/Desktop/Labour%20Force%20Survey%202018.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2018).

- Van Wyk, David, Cronje Freek, and Johann Van Wyk. 2009. Corporate Social Responsibility in the Diamond Mining Industry on the West Coast of South Africa. Policy Gap 4, SADC Research Report. Johannesburg: Bench Marks Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn, Melinda, and Lori Ryan. 2006. Corporate Governance in South Africa. Corporate Governance 14: 504–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, Denise. 2006. Between deliberative and participatory democracy. Journal of Philosophy and Social Criticism 32: 739–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Wide Fund. 2011. Coal and Water Futures in South Africa. Available online: http://awsassets.wwf.org.za/downloads/wwf_coal_water_report_2011_web.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2014).

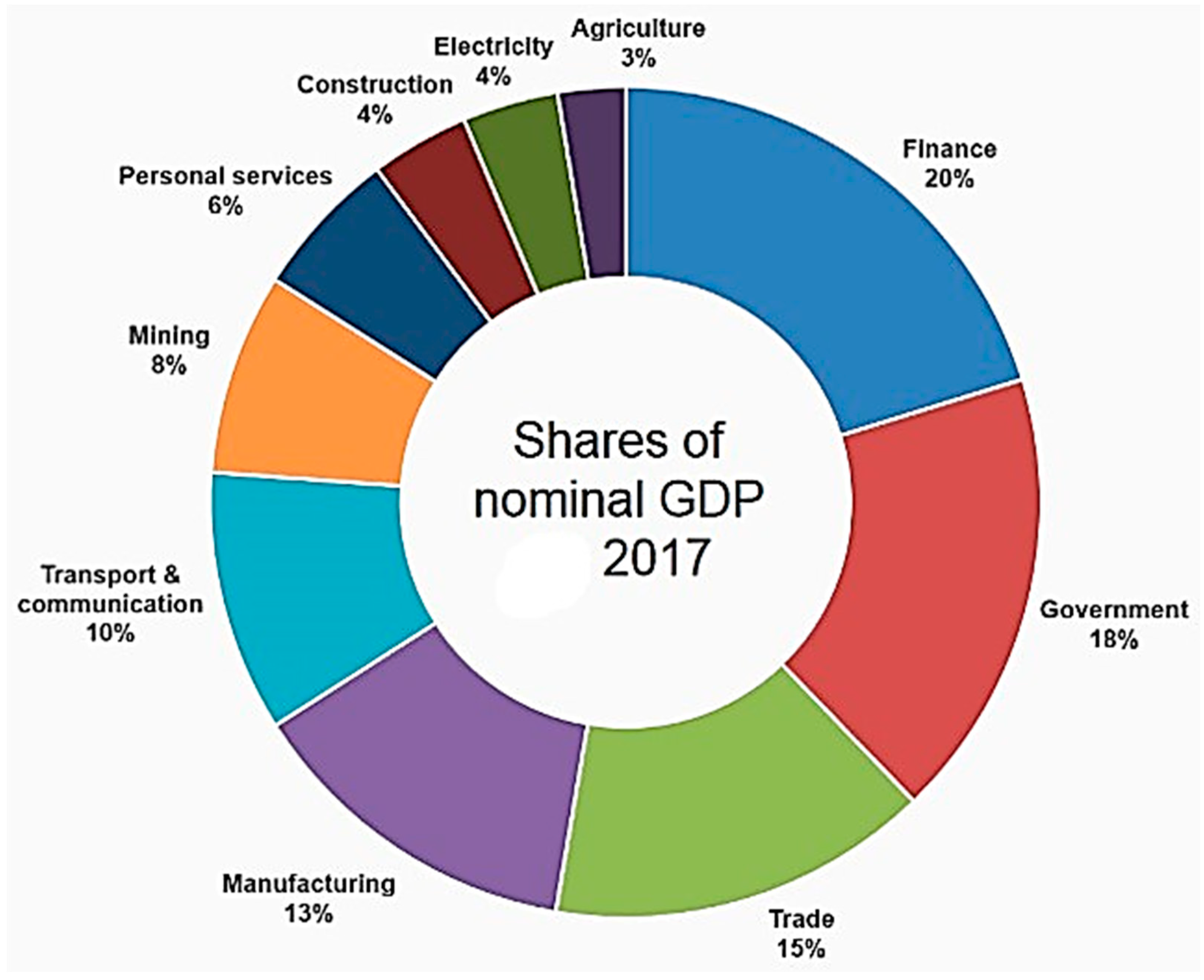

| 1 | The GDP is a monetary measure of the market value for the final total of goods and services produced in a period. Nominal GDP includes changes in prices due to inflation or a rise in the overall price level. |

| Industry | April–June 2017 | January–March 2018 | April–June 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total (Thousand) | 16,100 | 16,378 | 16,288 |

| Agriculture | 835 | 847 | 843 |

| Mining | 434 | 397 | 435 |

| Manufacturing | 1799 | 1849 | 1744 |

| Utilities | 148 | 143 | 161 |

| Construction | 1395 | 1431 | 1476 |

| Trade | 3265 | 3276 | 3219 |

| Transport | 954 | 960 | 1014 |

| Finance and other business services | 2395 | 2402 | 2399 |

| Community and social services | 3560 | 3785 | 3692 |

| Private households | 1311 | 1275 | 1296 |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leonard, L. Mining Corporations, Democratic Meddling, and Environmental Justice in South Africa. Soc. Sci. 2018, 7, 259. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7120259

Leonard L. Mining Corporations, Democratic Meddling, and Environmental Justice in South Africa. Social Sciences. 2018; 7(12):259. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7120259

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeonard, Llewellyn. 2018. "Mining Corporations, Democratic Meddling, and Environmental Justice in South Africa" Social Sciences 7, no. 12: 259. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7120259

APA StyleLeonard, L. (2018). Mining Corporations, Democratic Meddling, and Environmental Justice in South Africa. Social Sciences, 7(12), 259. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7120259