Using the Lens of ‘Possible Selves’ to Explore Access to Higher Education: A New Conceptual Model for Practice, Policy, and Research

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Policy and Practice Context

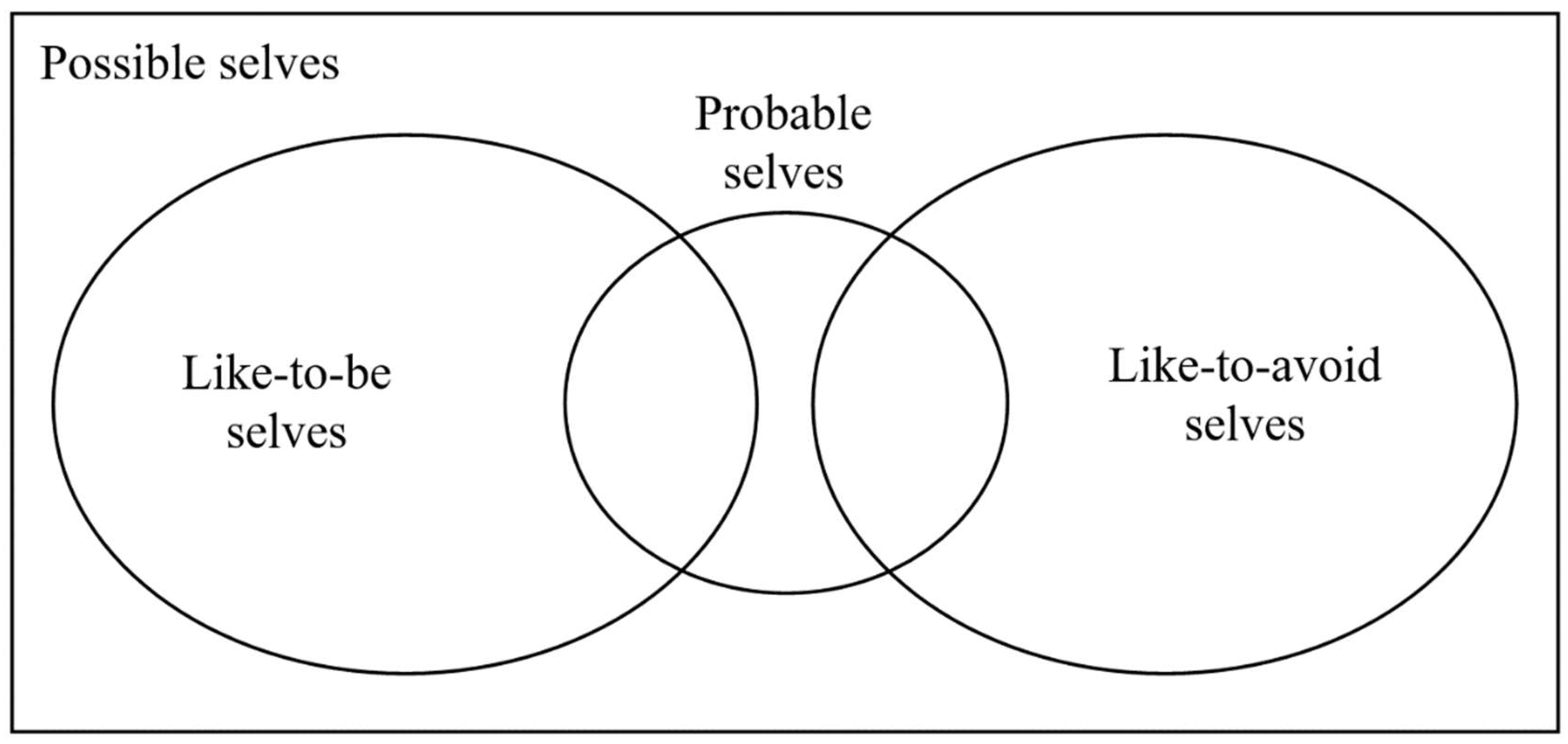

2. The Theory of Possible Selves

‘The working self-concept derives from the set of self-conceptions that are presently active in thought and memory. It can be viewed as a continually active, shifting array of available self-knowledge. The array changes as individuals experience variation in internal states and social circumstances’.

‘Possible selves […] can be viewed as cognitive bridges between the present and the future, specifying how individuals may change from how they are now to what they will become. When certain self-conceptions are challenged or supported, it is often the nature of the activated possible selves that determines how the individual feels and what course the subsequent action will take’.

‘An individual is free to create any variety of possible selves, yet the pool of possible selves derives from the categories made salient by the individual’s particular sociocultural and historical context and from the models, images, and symbols provided by the media and by the individual’s immediate social experiences. Possible selves thus have the potential to reveal the inventive and constructive nature of the self but they also reflect the extent to which the self is socially determined and constrained’.

‘Possible selves give specific, self-relevant form, meaning, and direction to one’s hopes and threats. Possible selves are specific representations of one’s self in future states and circumstances that serve to organize and energize one’s actions’.

‘possible selves are not likely to become elaborated and thereby either motivationally or behaviourally effective unless valuing them and believing in them are supported or encouraged by significant others’.

‘an individual’s estimate of the probability of certain possible selves, both positive and negative, considerably augmented our ability to explain current affective and motivational states’.(Markus and Nurius 1987, p. 167—original emphasis)

2.1. Possible Selves, Educational Outcomes and Intergroup Differences

2.2. Summary: Possible Selves and Aspirations

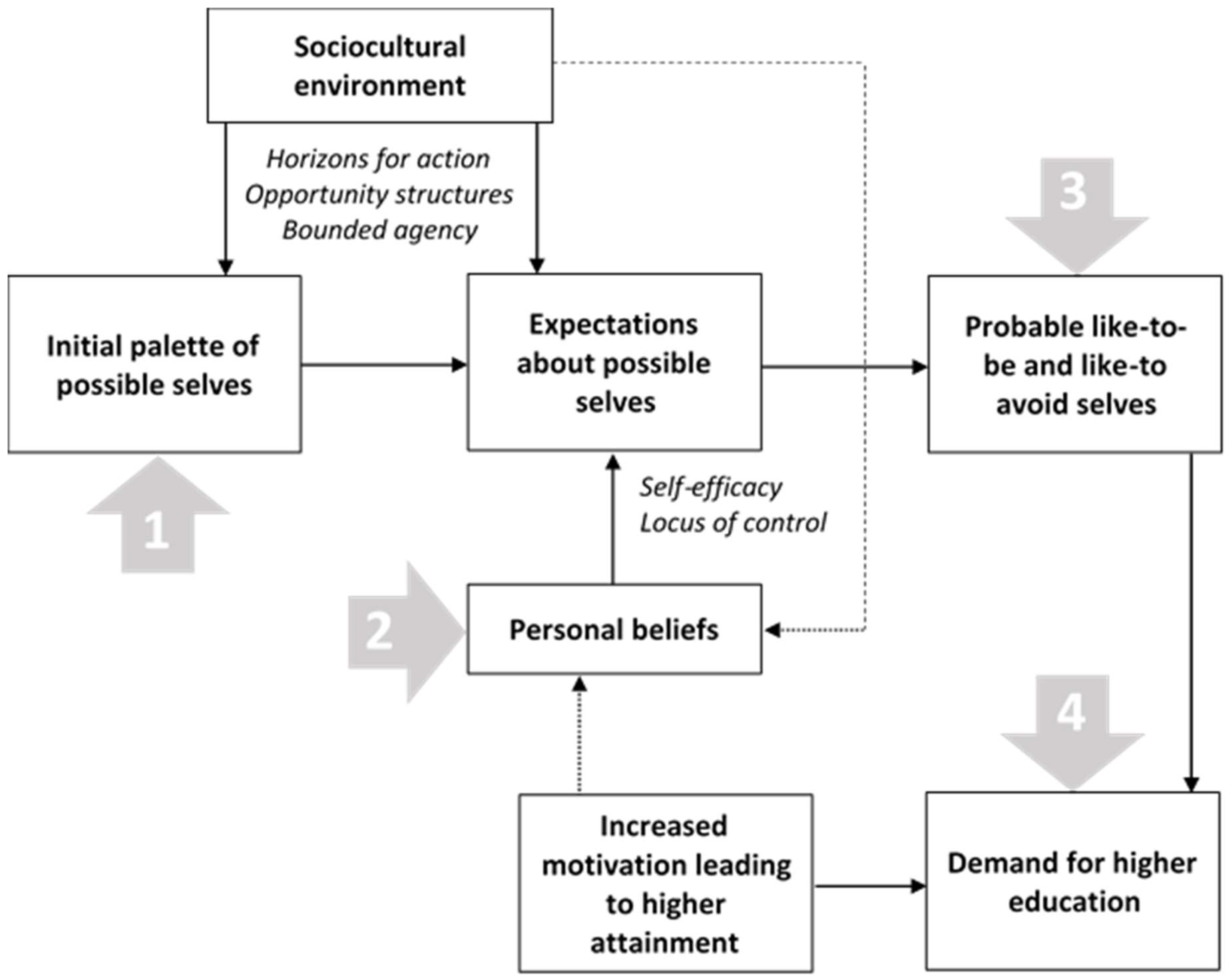

3. Building a Conceptual Model

‘Horizons for action both limit and enable our view of the world and the choices we can make within it. Thus, the fact that there are jobs for girls in engineering is irrelevant if a young woman does not perceive engineering as an appropriate career’.

4. Implications for Practice

- Intervention Point 1 relates to the palette of possible selves that is available to the individual: what is the pool from which they are able to pursue like-to-be selves or identify like-to-avoid selves? While the size of the pool may not differ markedly between advantaged and disadvantaged young people (Oyserman et al. 2011), the latter are likely to envisage fewer possible selves that are predicated on requiring a degree. This is in part due to their horizons for action, which inform their concepts of what it is possible to be in their own sociocultural context. An intervention at this point would seek to expand the pool of possible selves available that have a relationship to higher education—or to education more generally. These may be occupationally-driven or focused on demonstrating how wider possible selves (e.g., ‘me as homeowner’) are reliant on educational success. In particular, such interventions might seek to strengthen the perceived relationship between education and wider life outcomes. For example, Oyserman et al. (2002, pp. 317–18) describe an activity where young people choose from a selection of images of adults as a vehicle for group discussions around ‘work, family, lifestyle, community service, health, and hobbies’. This sort of activity provides an experiential opportunity to engage with possible selves that have not previously been considered and to potentially add them, perhaps only in outline, to the palette of futures that might be available; what Archer et al. (2014, p. 77) call ‘diversifying’ aspirations. Importantly, such activities would not over-emphasise possible selves as ‘me as a student’ or ‘me as a graduate’, but rather the wider selves to which these states give access. Perhaps more controversially, these activities may also seed conversations about like-to-avoid selves (Ruvolo and Markus 1992; Oyserman et al. 2015).

- Intervention Point 2 relates to engaging with the young person’s beliefs about their ability to exercise control over their future and their ability to succeed at tasks that are important to them. As discussed in the previous section, these are hypothesised to be important vectors in determining the likelihood of a possible self coming to pass and, whereas the wider sociocultural context cannot readily be influenced in the short-term, interventions that challenge these personal beliefs are likely to be successful in shaping what selves appear probable. This is perhaps most important where the probable selves identified by the young person are negative (i.e., like-to-avoid), but where they expect that they will not be able to avoid them due to structural constraints and their own inability to exercise effective agency over their future. Successful interventions are likely to focus on reinforcing the young person’s perceived ability to be successful through supported short-term tasks and a process of reflection that actively demonstrates their potential for more sustained forms of success. Such interventions are likely to be longitudinal in nature, focusing on self-efficacy and/or locus of control or be more academically-focused on the development of a ‘learning orientation’ (Watkins 2010) and metacognitive skills that help young people to understand how they learn; what St. Clair et al. (2013, p. 736) call a ‘day to day process of supporting students to learn how to attain what they want’. They may also engage particularly with parents and teachers as key influencers to ensure that their own expectations are positive, realistic and transmitted to young people (Cummings et al. 2012; Harrison and Waller 2018).

- Intervention Point 3 comes when the young person is beginning to elaborate like-to-be (or like-to-avoid) selves that they feel are probable in their context. This process involves translating their vision of themselves in the future into something that is vivid and detailed in order to provide the motivational impetus that results from integrating this vision into their working self-concept. Oyserman et al. (2002) argue that it is important that young people are allowed to elaborate their own possible selves, rather than passively receive insights from adults about how they should visualise them and what their roadmaps should be. Instead, based on their own experiences of devising and evaluating an intervention, they advocate for a process of providing supported space for young people to identify why their like-to-be selves are important to them and how they might be achieved; this is cognate to the reflecting and growing steps advocated by Hock et al. (2006). Specifically, this is less directive than traditional approaches to careers guidance, with a wider scope beyond the occupational. Activities might include workshops where young people are encouraged to produce actions plans and opportunities to engage with adults embodying the like-to-be selves or to ‘try on’ these selves—for example, through work experience programmes (St. Clair et al. 2013; Waller et al. 2014) or mentoring (Packard and Nguyen 2003; Cummings et al. 2012). The conceptual shift here is away from directive guidance that seeks to coerce young people and towards guided individualised activities that enable them to explore their own futures and devise self-relevant strategies to align their like-to-be selves with their probable selves (Yowell 2002).

- Intervention Point 4 specifically comes as the individual is considering higher education and comes closest to echoing existing aspiration-raising practices with their focus on making higher education appear desirable and realistic. Typically, this includes exposure to a campus environment, involvement in inspirational experiences, collaboration with current students, and information about graduate careers and other opportunities to envisage oneself as a student and/or graduate (Harrison and Waller 2017, 2018). These activities still retain value under a possible selves approach as they form part of the process of elaboration and reinforcement that embeds like-to-be selves involving higher education within the self-concept. However, these activities are unlikely to be transformational for disadvantaged young people without the wider context and individualised strategies provided by the earlier interventions.

5. Implications for Policy

6. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ajzen, Icek. 2002. Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 32: 665–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appadurai, Arjun. 2004. The capacity to aspire: Culture and the terms of recognition. In Culture and Public Action. Edited by Vijayendra Rao and Michael Walton. Stanford: Stanford University Press, pp. 59–84. ISBN 978-0-80474-787-5. [Google Scholar]

- Archer, Louise. 2007a. Diversity, equality and higher education: a critical reflection on the ab/uses of equity discourse within widening participation. Teaching in Higher Education 12: 635–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, Margaret. 2007b. Making Our Way through the World: Human Reflexivity and Social Mobility. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-52169-693-7. [Google Scholar]

- Archer, Louise, Jennifer DeWitt, and Billy Wong. 2014. Spheres of influence: What shapes young people’s aspirations at age 12/13 and what are the implications for education policy? Journal of Education Policy 29: 58–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Will, Pam Sammons, Iram Siraj-Blatchford, Kathy Sylva, Edward C. Melhuish, and Brenda Taggart. 2014. Aspirations, education and inequality in England: insights from the effective provision of pre-school, primary and secondary education project. Oxford Review of Education 40: 525–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, Albert. 1977. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review 84: 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, Albert. 1982. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist 37: 122–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathmaker, Ann-Marie, Nicola Ingram, Jessie Abrahams, Anthony Hoare, Richard Waller, and Harriet Bradley. 2016. Higher Education, Social Class and Social Mobility: The Degree Generation. London: Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 978-1-349-71010-2. [Google Scholar]

- Boardman, Jason D., and Stephanie A. Robert. 2000. Neighborhood socioeconomic status and perceptions of self-efficacy. Sociological Perspectives 43: 117–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bok, Jessica. 2010. The capacity to aspire to higher education: ‘It’s like making them do a play without a script’. Critical Studies in Education 51: 163–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boliver, Vikki. 2016. Exploring ethnic inequalities in admission to Russell Group universities. Sociology 50: 247–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Boudon, Raymond. 1974. Education, Opportunity and Social Inequality: Changing Prospects in Western Society. London: Wiley, ISBN 978-0-47109-105-9. [Google Scholar]

- Boxer, Paul, Sara E. Goldstein, Tahlia DeLorenzo, Sarah Savoy, and Ignacio Mercado. 2011. Educational aspiration–expectation discrepancies: Relation to socioeconomic and academic risk-related factors. Journal of Adolescence 34: 609–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breen, Richard, and John H. Goldthorpe. 1997. Explaining educational differences: Towards a formal rational action theory. Rationality and Society 9: 275–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breen, Richard, Herman G. van der Werfhorst, and Mads Meier Jaeger. 2014. Deciding under doubt: A theory of risk aversion, time discounting preferences, and educational decision-making. European Sociological Review 30: 258–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, Penny Jane. 2012. The Right to Higher Education: Beyond Widening Participation. Abingdon: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-41556-824-1. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, Ciaran. 2015. Culture, Capitals and Graduate Futures: Degrees of Class. Abingdon: Routledge, ISBN 978-1-13884-053-9. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, Judith. 2018. OFSTED Chief Says Poor White Communities ‘Lack Aspiration and Drive’. June 21. Available online: www.bbc.co.uk/news/education-44568019 (accessed on 13 August 2018).

- Chevalier, Arnaud, Steve Gibbons, Andy Thorpe, Martin Snell, and Sherria Hoskins. 2009. Students’ academic self-perception. Economics of Education Review 28: 716–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdry, Haroon, Claire Crawford, and Alice Goodman. 2010. Explaining the Socioeconomic Gradient in Child Outcomes During the Secondary School Years: Evidence from the Longitudinal Study of Young People in England. London: Institute for Fiscal Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Clayton, John, Gill Crozier, and Diane Reay. 2009. Home and away: Risk, familiarity and the multiple geographies of the higher education experience. International Studies in Sociology of Education 19: 157–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, Claire. 2014. The Link between Secondary School Characteristics and University Participation and Outcomes; London: Department for Education.

- Crawford, Claire, and Ellen Greaves. 2015. Socio-Economic, Ethnic and Gender Differences in HE Participation. London: Institute for Fiscal Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Croll, Paul, and Gaynor Attwood. 2013. Participation in higher education: Aspirations, attainment and social background. British Journal of Educational Studies 61: 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, Susan, and Hazel Markus. 1991. Possible selves across the life span. Human Development 34: 230–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, Colleen, Karen Laing, James Law, Janice McLaughlin, Ivy Papps, Liz Todd, and Pam Woolner. 2012. Can Changing Aspirations and Attitudes Impact on Educational Attainment? A Review of Interventions. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Business, Innovation and Skills. 2014. National Strategy for Access and Student Success in Higher Education. London: DBIS. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Education. 2016. Higher Education: Success as a Knowledge Economy; London: DFE.

- Department for Education. 2017. Widening Participation in Higher Education: 2017; London: DFE.

- Department for Education and Skills. 2003. The Future of Higher Education; Norwich: HMSO.

- Dittmann, Andrea G., and Nicole M. Stephens. 2017. Interventions aimed at closing the social class achievement gap: Changing individuals, structures, and construals. Current Opinion in Psychology 18: 111–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erikson, Martin G. 2007. The meaning of the future: Toward a more specific definition of possible selves. Review of General Psychology 11: 348–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, Karen. 2007. Concepts of bounded agency in education, work, and the personal lives of young adults. International Journal of Psychology 42: 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fuller, Carol. 2014. Social capital and the role of trust in aspirations for higher education. Educational Review 66: 131–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddens, Anthony. 1991. Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age. Cambridge: Polity Press, ISBN 978-0-74560-932-4. [Google Scholar]

- Gorard, Stephen, Nick Adnett, Helen May, Kim Slack, Emma Smith, and Liz Thomas. 2007. Overcoming the Barriers to Higher Education. Stoke-on-Trent: Trentham Books, ISBN 978-1-85856-414-2. [Google Scholar]

- Gorard, Stephen, Beng Huat See, and Peter Davies. 2012. The Impact of Attitudes and Aspirations on Educational Attainment and Participation. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Green, Francis, Samantha Parsons, Alice Sullivan, and Richard Wiggins. 2018. Dreaming big? Self-valuations, aspirations, networks and the private-school earnings premium. Cambridge Journal of Economics 42: 757–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardgrove, Abby, Esther Rootham, and Linda McDowell. 2015. Possible selves in a precarious labour market: Youth, imagined future and transitions to work in the UK. Geoforum 60: 163–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, Neil. 2017. Patterns of participation in a period of change: Social trends in English higher education from 2000 to 2016. In Higher Education and Social Inequalities: University Admissions, Experiences, and Outcomes. Edited by Richard Waller, Nicola Ingram and Michael R. M. Ward. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 54–80. ISBN 978-1-31544-970-8. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, Neil. Forthcoming. Students-as-insurers: rethinking ‘risk’ for disadvantaged young people considering higher education in England. Journal of Youth Studies. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, Neil, and Richard Waller. 2017. Success and impact in widening participation policy: What works and how do we know? Higher Education Policy 30: 141–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, Neil, and Richard Waller. 2018. Challenging discourses of aspiration: The role of expectations and attainment in access to higher education. British Educational Research Journal 44: 914–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, Neil, Katy Vigurs, Julian Crockford, Colin McCaig, Ruth Squire, and Lewis Clark. Forthcoming. Understanding the evaluation of outreach interventions for under 16 year olds. Bristol: Office for Students.

- Henderson, Holly. 2018. Borrowed time: A sociological theorisation of possible selves and educational subjectivities. In Possible Selves and Higher Education: New Interdisciplinary Insights. Edited by Holly Henderson, Jacqueline Stevenson and Ann-Marie Bathmaker. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 27–40. ISBN 978-1-138-09803-9. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, Holly, Jacqueline Stevenson, and Ann-Marie Bathmaker. 2018. Possible Selves and Higher Education: New Interdisciplinary Insights. Abingdon: Routledge, ISBN 978-1-138-09803-9. [Google Scholar]

- Higher Education Funding Council for England. 2016. National Collaborative Outreach Programme: Invitation to Submit Proposals for Funding. Bristol: HEFCE. [Google Scholar]

- Hock, Michael F., Donald D. Deshler, and Jean B. Schumaker. 2006. Enhancing student motivation through the pursuit of possible selves. In Possible Selves: Theory Research and Applications. Edited by Curtis Dunkel and Jennifer Kerpelman. Hauppauge: Nova Science Publishers, pp. 205–21. ISBN 978-1-59454-431-6. [Google Scholar]

- Hodkinson, Phil. 1995. How young people make career decisions. Education + Training 37: 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodkinson, Phil, and Andrew C. Sparkes. 1993. Young people’s career choices and careers guidance action planning: A case-study of training credits in action. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling 21: 246–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodkinson, Phil, and Andrew C. Sparkes. 1997. Careership: A sociological theory of career decision making. British Journal of Sociology of Education 18: 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Steven. 2012. The Personal Statement: A Fair Way to Assess University Applicants? London: Sutton Trust. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Robert, and Liz Thomas. 2005. The 2003 UK Government higher education White Paper: A critical assessment of its implications for the access and widening participation agenda. Journal of Education Policy 20: 615–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattab, Nabil. 2015. Students’ aspirations, expectations and school achievement: What really matters? British Educational Research Journal 41: 731–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, Chris Michael, Rhonda K. Lewis, Angela Scott, Denise Wren, Corinne Nilsen, and Deltha Q. Colvin. 2012. Exploring the educational aspirations–expectations gap in eighth grade students: Implications for educational interventions and school reform. Educational Studies 38: 507–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, Michele. 2006. Gender and possible selves. In Possible Selves: Theory Research and Applications. Edited by Curtis Dunkel and Jennifer Kerpelman. Hauppauge: Nova Science Publishers, pp. 61–77. ISBN 978-1-59454-431-6. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, Michael W., Paul K. Piff, and Dacher Keltner. 2009. Social class, sense of control, and social explanation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 97: 992–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landau, Mark J., Jesse Barrera, and Lucas A. Keefer. 2017. On the road: combining possible identities and metaphor to motivate disadvantaged middle-school students. Metaphor and Symbol 32: 276–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leathwood, Carole, and Paul O’Connell. 2003. ‘It’s a struggle’: The construction of the ‘new student’ in higher education. Journal of Education Policy 18: 597–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefcourt, Herbert M. 2014. Locus of Control: Current Trends in Theory and Research, 2nd ed. Hove: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leondari, Angeliki. 2007. Future time perspective, possible selves, and academic achievement. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education 117: 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leondari, Angeliki, and Eleftheria N. Gonida. 2008. Adolescents’ possible selves, achievement goal orientations, and academic achievement. Hellenic Journal of Psychology 5: 179–98. [Google Scholar]

- Leondari, Angeliki, Efi Syngollitou, and Grigoris Kiosseoglou. 1998. Academic achievement, motivation and future selves. Educational Studies 24: 153–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumb, Matt. 2018. Unintended imaginings: The difficult dimensions of possible selves. In Possible Selves and Higher Education: New Interdisciplinary Insights. Edited by Holly Henderson, Jacqueline Stevenson and Ann-Marie Bathmaker. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 93–110. ISBN 978-1-138-09803-9. [Google Scholar]

- Marginson, Simon. 2017. The stratification of opportunity in high participation systems (HPS) of higher education. In Access to Higher Education: Theoretical Perspectives and Contemporary Challenges. Edited by Anna Mountford-Zimdars and Neil Harrison. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 33–48. ISBN 978-1-138-92410-9. [Google Scholar]

- Markus, Hazel, and Paula Nurius. 1986. Possible selves. American Psychologist 41: 954–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, Hazel, and Paula Nurius. 1987. Possible selves: The interface between motivation and the self-concept. In Self and Identity: Psychosocial Perspectives. Edited by Krysia Yardley and Terry Honess. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 157–72. ISBN 978-0-47191-125-8. [Google Scholar]

- Markus, Hazel, and Ann Ruvolo. 1989. Possible selves: Personalized representations of goals. In Goal Concepts in Personality and Social Psychology. Edited by Lawrence A. Pervin. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum, pp. 211–41. ISBN 978-0-80580-383-9. [Google Scholar]

- McCaig, Colin. 2018. English higher education: Widening participation and the historical context for system differentiation. In Equality and Differentiation in Marketised Higher Education: A New Level Playing Field? Edited by Marion Bowl, Colin McCaig and Jonathan Hughes. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 73–93. ISBN 978-3-319-78312-3. [Google Scholar]

- Merton, Robert K. 1968. Social Theory and Social Structure. New York: Free Press, ISBN 978-0-02921-130-4. [Google Scholar]

- National Committee of Inquiry into Higher Education. 1997. Higher Education in the Learning Society; Norwich: HMSO.

- Nurius, Paula. 1991. Possible selves and social support. In The Self-Society Dynamic: Cognition, Emotion, and Action. Edited by Judith A. Howard and Peter L. Callero. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 239–58. ISBN 978-0-52138-433-9. [Google Scholar]

- Office for Fair Access. 2016. Outcomes of Access Agreement Monitoring for 2014–15. Bristol: OFFA. [Google Scholar]

- Oyserman, Daphna, and Stephanie Fryberg. 2006. The possible selves of diverse adolescents: Content and function across gender, race and national origin. In Possible Selves: Theory Research and Applications. Edited by Curtis Dunkel and Jennifer Kerpelman. Hauppauge: Nova Science Publishers, pp. 17–39. ISBN 978-1-59454-431-6. [Google Scholar]

- Oyserman, Daphna, Kathy Terry, and Deborah Bybee. 2002. A possible selves intervention to enhance school involvement. Journal of Adolescence 25: 313–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyserman, Daphna, Deborah Bybee, Kathy Terry, and Tamera Hart-Johnson. 2004. Possible selves as roadmaps. Journal of Research in Personality 38: 130–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyserman, Daphna, Deborah Bybee, and Kathy Terry. 2006. Possible selves and academic outcomes: How and when possible selves impel action. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 91: 188–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyserman, Daphna, Daniel Brickman, and Marjorie Rhodes. 2007. School success, possible selves, and parent school involvement. Family Relations 56: 479–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyserman, Daphna, Elizabeth Johnson, and Leah James. 2011. Seeing the destination but not the path: Effects of socioeconomic disadvantage on school-focused possible self content and linked behavioral strategies. Self and Identity 10: 474–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyserman, Daphna, Mesmin Destin, and Sheida Novin. 2015. The context-sensitive future self: Possible selves motivate in context, not otherwise. Self and Identity 14: 173–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packard, Becky Wai-Ling, and Dam Nguyen. 2003. Science career-related possible selves of adolescent girls: A longitudinal study. Journal of Career Development 29: 251–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papafilipou, Vanda, and Laura Bentley. 2017. Gendered transitions, career identities and possible selves: The case of engineering graduates. Journal of Education and Work 30: 827–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, Dana. 2014. What about place? Considering the role of physical environment on youth imagining of future possible selves. Journal of Youth Studies 17: 697–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raffe, David, and Linda Croxford. 2015. How stable is the stratification of higher education in England and Scotland? British Journal of Sociology of Education 36: 313–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raphael Reed, Lynn, Peter Gates, and Kathryn Last. 2007. Young Participation in Higher Education in the Parliamentary Constituencies of Birmingham Hodge Hill, Bristol South, Nottingham North and Sheffield Brightside. Bristol: University of the West of England. [Google Scholar]

- Reay, Diane. 2017. A tale of two universities: Class work in higher education. In Higher Education and Social Inequalities: University Admissions, Experiences, and Outcomes. Edited by Richard Waller, Nicola Ingram and Michael R. M. Ward. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 82–98. ISBN 978-1-31544-970-8. [Google Scholar]

- Reay, Diane, Miriam E. David, and Stephen Ball. 2005. Degrees of Choice: Class, Race, Gender and Higher Education. Stoke-on-Trent: Trentham Books, ISBN 978-1-85856-330-5. [Google Scholar]

- Reay, Diane, Gill Crozier, and John Clayton. 2010. ‘Fitting in’ or ‘standing out’: Working class students in UK higher education. British Educational Research Journal 36: 107–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, Ken. 1968. The entry into employment: An approach towards a general theory. Sociological Review 16: 165–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, Ken. 2009. Opportunity structures then and now. Journal of Education and Work 22: 355–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossiter, Marsha. 2009. Possible selves and career transitions. Implications for serving non-traditional students. Journal of Continuing Higher Education 57: 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruvolo, Ann Patrice, and Hazel Rose Markus. 1992. Possible selves and performance: The power of self-relevant imagery. Social Cognition 10: 95–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Lisa. 2011. Experiential ‘hot’ knowledge and its influence on low-SES students’ capacities to aspire to higher education. Critical Studies in Education 52: 165–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolentseva, Anna. 2017. Participation and access in higher education in Russia: Continuity and change of a positional advantage. In Access to Higher Education: Theoretical Perspectives and Contemporary Challenges. Edited by Anna Mountford-Zimdars and Neil Harrison. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 190–204. ISBN 978-1-138-92410-9. [Google Scholar]

- St Clair, Ralf, Keith Kintrea, and Muir Houston. 2013. Silver bullet or red herring? New evidence on the place of aspirations in education. Oxford Review of Education 39: 719–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, Jacqueline, and Sue Clegg. 2011. Possible selves: Students orientating themselves towards the future through extracurricular activity. British Educational Research Journal 37: 231–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, Ron. 2017. Explaining inequality? Rational action theories of educational decision making. In Access to Higher Education: Theoretical Perspectives and Contemporary Challenges. Edited by Anna Mountford-Zimdars and Neil Harrison. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 67–84. ISBN 978-1-138-92410-9. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, Ron, and Robin Simmons. 2013. Social mobility and post-compulsory education: Revisiting Boudon’s model of social opportunity. British Journal of Sociology of Education 34: 744–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Universities and Colleges Admissions Service. 2017. End of Cycle Report 2017: Patterns by Applicant Characteristics. Cheltenham: UCAS. [Google Scholar]

- Vroom, Victor H. 1964. Work and Motivation. New York: John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-0-78790-030-4. [Google Scholar]

- Waller, Richard, Neil Harrison, Sue Hatt, and Farooq Chudry. 2014. Undergraduates’ memories of school-based work experience and the role of social class in placement choices in the UK. Journal of Education and Work 27: 323–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, Richard, John Holford, Peter Jarvis, Marcella Milana, and Sue Webb. 2015. Neo-liberalism and the shifting discourse of ‘educational fairness’. International Journal of Lifelong Education 34: 619–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, Chris. 2010. Learning, Performance and Improvement. London: Institute of Education. [Google Scholar]

- Watts, A. G. 2013. False dawns, bleak sunset: The Coalition Government’s policies on career guidance. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling 41: 442–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, Sue, Penny Jane Burke, Susan Nichols, Steven Roberts, Garth Stahl, Steven Threadgold, and Jane Wilkinson. 2017. Thinking with and beyond Bourdieu in widening higher education participation. Studies in Continuing Education 39: 138–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winterton, Mandy Teresa, and Sarah Irwin. 2012. Teenage expectations of going to university: The ebb and flow of influences from 14 to 18. Journal of Youth Studies 15: 858–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, Beverley Anne. 2017. Diversifying admissions through top-down entrance examination reform in Japanese elite universities: What is happening on the ground? In Access to Higher Education: Theoretical Perspectives and Contemporary Challenges. Edited by Anna Mountford-Zimdars and Neil Harrison. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 216–31. ISBN 978-1-138-92410-9. [Google Scholar]

- Younger, Kirsty, Louise Gascoine, Victoria Menzies, and Carole Torgerson. 2018. Forthcoming. A systematic review of evidence on the effectiveness of interventions and strategies for widening participation in higher education. Journal of Further and Higher Education. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yowell, Constance M. 2002. Dreams of the future: The pursuit of education and career possible selves among ninth grade Latino youth. Applied Developmental Science 6: 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Harrison, N. Using the Lens of ‘Possible Selves’ to Explore Access to Higher Education: A New Conceptual Model for Practice, Policy, and Research. Soc. Sci. 2018, 7, 209. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7100209

Harrison N. Using the Lens of ‘Possible Selves’ to Explore Access to Higher Education: A New Conceptual Model for Practice, Policy, and Research. Social Sciences. 2018; 7(10):209. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7100209

Chicago/Turabian StyleHarrison, Neil. 2018. "Using the Lens of ‘Possible Selves’ to Explore Access to Higher Education: A New Conceptual Model for Practice, Policy, and Research" Social Sciences 7, no. 10: 209. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7100209