What Motivates Student Environmental Activists on College Campuses? An In-Depth Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

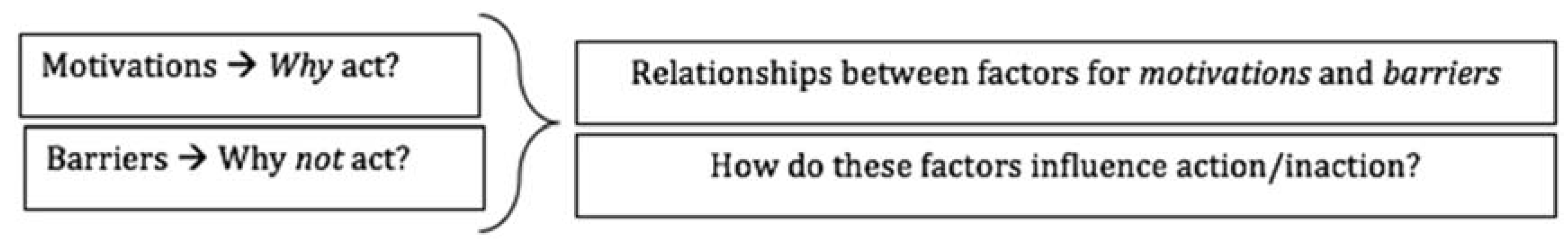

Conceptual Framework and Research Questions

2. Methods

2.1. Data Collection and Research Design

2.2. Participant and Study Site Selection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. What Motivates Environmental Activists on College Campuses?

3.1.1. Experience and Passion

…that is the year I started drinking soy milk instead of regular milk. That’s the year I put it together why beef was linked to environmental issues—before, I seriously was really stupid as far as…I was very uninformed…and I blame my undergrad career, really, because I was a journalism major and I think we should have had more requirements like human geography and I knew that there were all of these things out there that were wrong, and I just didn’t understand them. So, that’s really why I sought out the International Studies program to try to understand those things…I had the activist urge in me, but I didn’t have an outlet.

…it is all probably rooted back to how almost every family vacation we went on we would camp…I loved driving up north and seeing like all this—so I’m from [a really urban] area, so you don’t see that many stars, but—you know we’d go to [a very small town] and like, the sky would be lit up and as a child I would stare at it for hours, or you know, swimming in [the lake] and being able to see all the way to the bottom of the lake because they wouldn’t allow any motorized boats. And so, I really loved those vacations where we would just kind of like… we would camp, and would just relax, so I think I wanted to find a way to make sure that that was possible for my future kids to enjoy things like that as well. That’s where it probably started, was when I was a child, and my mom teaching me to clean up the campground so it’s nicer than when we left. But since then…I tried to, you know, how can I work this into my daily life? So, in high school, I started a recycling program at band camp, and you know, all these little things, and then I came to college and I learned that…the real change needs to happen, like in the fossil fuel industry, because we can be doing all these things and we can recycle and we can conserve water in our house. But it’s not going to amount to the amount of carbon like burning coal is putting into our atmosphere, or the billions of gallons of water hydraulic fracturing wastes every day, so it’s just…it’s where the change needs to happen.

3.1.2. Sense of Community

I fell into the coalition’s realm and started helping with community outreach. Coalitions is “targeted grassroots,” so it’s the grassroots realm [that] focuses mostly on educating the students on campus and getting the word out to students about our campaign, and problems with…whether burning fossil fuels or investing in fossil fuels. And then…coalitions kind of does that with community groups, and local businesses on [the main street downtown], other environmental organizations in [the area], or faith groups in the community, faculty members on campus, other student organizations, things like that.

…some people are confused about climate change…what’s happening, and how the university is contributing to that with where their money is. That’s why we’ve brought in somebody to talk about the climate, change as a problem, and we’ve also brought in somebody that can talk about solutions. Like alternatives to investing in the fossil fuel industry. And some people don’t even know what the word “divestment” means, so just like kind of to lay it all out there and explain why this is so important, not only in a worldly context, and how it affects the climate, but also at [the university].

…like, 20 environmentalists on campus yelling at them, but it was something the community as a whole wanted to see. [And to show them] that it wasn’t just, like, me, and being like a dirty hippie telling them to stop burning coal, but it was something that, you know, parents of schoolchildren wanted, and local business owners, and professors, and all this larger community wanted the university to stop burning coal.

3.1.3. Incentives and Self-Satisfaction

but overall, my goal that, when it doesn’t get tampered, or burdened by just being busy and things like that, is to do it not really for myself, but—Well, it is for myself, but I feel like I’m improving myself and also trying to improve the neighborhood and do something that I see as positive.

3.1.4. Engagement in Other Pro-Environmental Behaviors

By her description, she is “practicing what she preaches”, but that in itself is a form of activism. However, she emphasized that she has a problem with people who engage only in this form of activism. She doesn’t think activism should just be about what you consume, or about consumption. However, activism through the local food movement kicks in when people reconnect with and become “aware of the reasons that you’re eating local food and organic, not because it’s trendy, or it’s now…popular and expensive, but because a lot of people and a lot of natural environments are being exploited in the way you eat otherwise” (Annie 2013b). So the connections between PWYP, awareness, and community here are strong, and interact with each other in ways that help motivate a person to take action. Clearly, there is a strong relationship between her passion for activism and her decision to engage in other pro-environmental behaviors. For example, when asked why she would choose a more active form of activism versus “armchair activism,” Annie responded:By eating local, organic food grown by a farmer down the road, you’re supporting that farmer, you are decreasing the miles that your food traveled, and the environmental impacts of the pesticides and oil and everything that was not used in that food’s production, and you’re just, um…it’s kind of like that woman said at [that event] [she’s referring to a talk on food and place-making that occurred at an art gallery in the community] that every time you, you know…you kind of vote with your money.

Just…the feeling that I need to practice what I’m preaching, so if I’m studying something on a daily basis, and I’m, you know, telling people that “You shouldn’t eat that way” or “You should— “not that I’m, you know, demanding people change their habits. But if I’m going to be passionate about these things and want other people to change, then I have to change myself. So it’s like that “be the change you want to see in the world” cliché thing.

…A lot of times, we talked about how we ourselves could make a difference, like to be more environmentally-friendly, and I think that’s important for us, as environmental activists, to kind of live in the way we want to see the world, but at the same time, something wasn’t clicking. “Well I can do all I want, like I can use my reusable water bottle, and you know, I can try to eat foods that are less carbon-emitting, but if the university is burning all this coal right down the street—shouldn’t I be focusing on that?” And that’s where we can really make a difference, for people and the environment. So that’s kind of why I decided to switch.

3.2. What Prevents Action?

3.2.1. Involvement

…I saw a bunch of people kind of close to the entrance and they were just gardening, and there was an older woman working there who just was a volunteer, and I said “Hey, I just wanted to see, you know, what are you guys doing in here, what kind of stuff do you have going on,” and then she was like, “I don’t know.” She wasn’t, I don’t think, a very good volunteer because she was just like, “I’ll get someone else to tell you.” So then, [another woman], who’s the main—the gardenhouse manager—she came and talked to me, and it wasn’t until probably another six months at least until I started volunteering there.

…I honestly don’t think [the manager] did a[n] excellent job of explaining [either], because if she had explained it better I probably would have wanted to start volunteering before, but she just kind of said, “You know, we have this gardenhouse,” and she just—maybe I don’t remember but she didn’t make it clear that anyone can volunteer if they want, that they have this CSA, which I now participate in, but it was just sort of a more, like, “this is what we’re doing” but I didn’t get the sense that it was something that people could easily get involved with.

3.2.2. Time

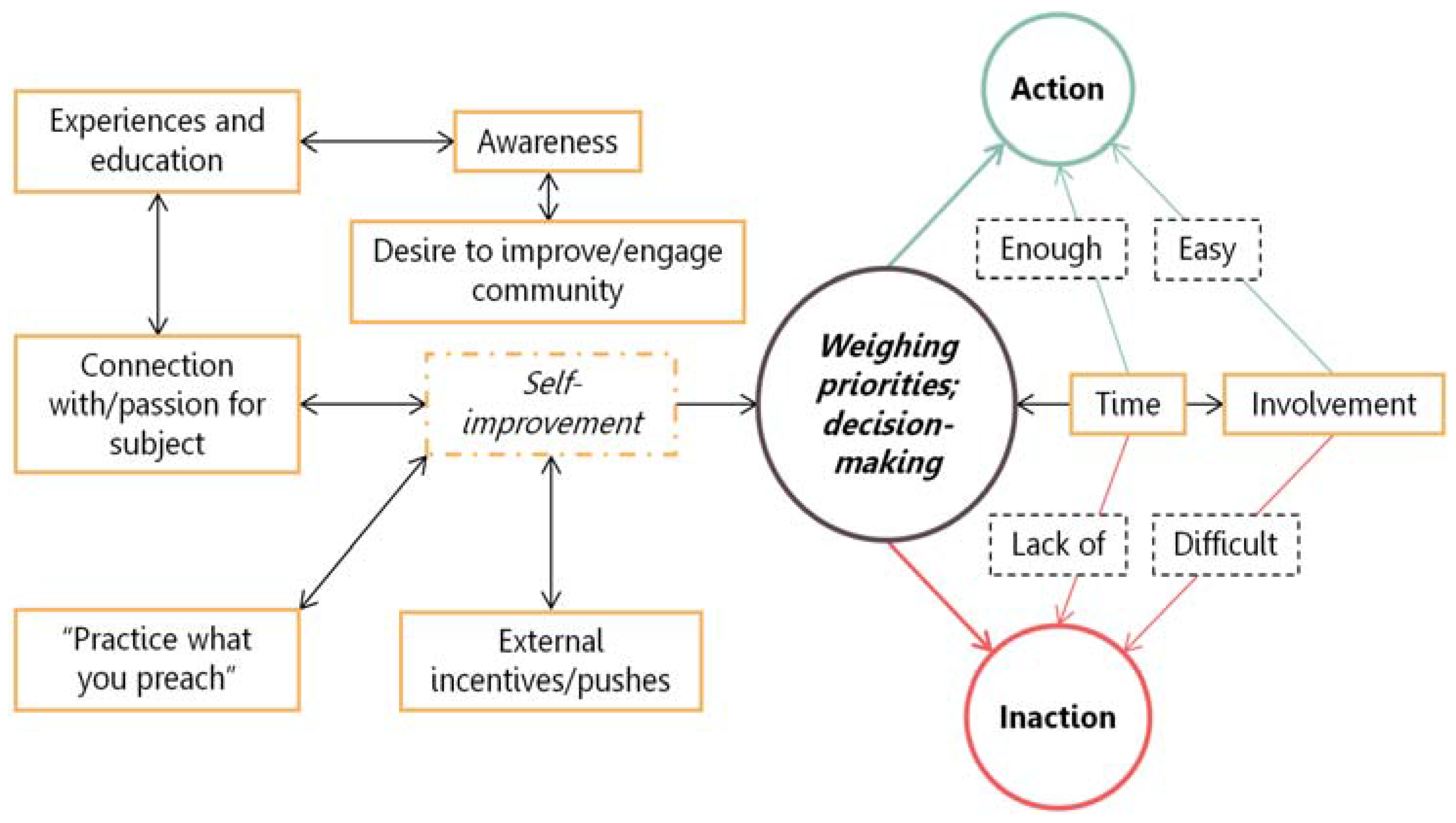

Again, we see in these statements the convergence of several themes: time, passion, and, possibly, involvement. The interrelatedness of these themes is reflected in all of the discussions above (Figure 2). Activist motivations are not standalone phenomena; they work in tandem with other processes and motivation factors in a dynamic way and are influenced by an individual’s history, previous experiences, constraints, values, and other external forces.“There was a point where I was trying to do all three [environmental organizations], and it was just too much, so the tactics and strategy in [this group] were the ones that I could relate to the most”.

3.3. Limitations and Proposals for Future Work

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adams, Ellis Adjei. 2014. Behavioral attitudes towards water conservation and re-use among the United States public. Resources and Environment 4: 162–67. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, Richard P., and Judy Goggin. 2005. What do we mean by “civic engagement”? Journal of Transformative Education 3: 236–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andolina, Molly W., Krista Jenkins, Cliff Zukin, and Scott Keeter. 2003. Habits from home, lessons from school: Influences on youth civic engagement. PS: Political Science and Politics 36: 275–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annie. 2013a. Interview by Cadi Y. Fung. Semi-structured sinterview. February 20. [Google Scholar]

- Annie. 2013b. Interview by Cadi Y. Fung. Follow-up semi-structured interview. March 15. [Google Scholar]

- Balsano, Aida B. 2005. Youth civic engagement in the United States: Understanding and addressing the impact of social impediments on positive youth and community development. Applied Developmental Science 9: 188–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beth. 2013. Interview by Cadi Y. Fung. Semi-structured interview. April 1. [Google Scholar]

- Botetzagias, Iosif, and Wijbrandt van Schuur. 2010. Active greens: An analysis of the determinants of green party members’ activism in environmental movements. Environment and Behavior 44: 509–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brody, Samuel, Himanshu Grover, and Arnold Vedlitz. 2012. Examining the willingness of Americans to alter behaviour to mitigate climate change. Climate Policy 12: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, Louise, and Debra Flanders Cushing. 2007. Education for strategic environmental behavior. Environmental Education Research 13: 437–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, Christopher F., Matthew J. Kotchen, and Michael R. Moore. 2003. Internal and external influences on pro-environmental behavior: Participation in a green electricity program. Journal of Environmental Psychology 23: 237–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcoran, Peter Blaze. 1999. Formative influences in the lives of environmental educators in the United States. Environmental Education Research 5: 207–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, Judith I., and Linda Steg. 2008. Value orientations to explain beliefs related to environmental significant behavior: How to measure egoistic, altruistic, and biospheric value orientations. Environment and Behavior 40: 330–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delli Carpini, Michael X. 2000. Gen. com: Youth, civic engagement, and the new information environment. Political Communication 17: 341–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, Thomas, Paul C. Stern, and Gregory A. Guagnano. 1998. Social structural and social psychological bases of environmental concern. Environment and Behavior 30: 450–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dono, Joanne, Janine Webb, and Ben Richardson. 2010. The relationship between environmental activism, pro-environmental behavior and social identity. Journal of Environmental Psychology 30: 178–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, Kelly S., Rachel McDonald, and Winnifred R. Louis. 2008. Theory of planned behaviour, identity and intentions to engage in environmental activism. Journal of Environmental Psychology 28: 318–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, Constance, and Peter Levine. 2010. Civic engagement and the transition to adulthood. The Future of Children 20: 159–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galston, William A. 2004. Civic education and political participation. PS: Political Science and Politics 37: 263–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigliotti, Larry M. 1994. Environmental issues: Cornell students’ willingness to take action, 1990. The Journal of Environmental Education 26: 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grønhøj, Alice, and John Thøgersen. 2012. Action speaks louder than words: The effect of personal attitudes and family norms on adolescents’ pro-environmental behaviour. Journal of Economic Psychology 33: 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillaume, Casta, Robert Jagers, and Deborah Rivas-Drakeand. 2015. Middle school as a developmental niche for civic engagement. American Journal of Community Psychology 56: 321–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansla, André, Amelie Gamble, Asgeir Juliusson, and Tommy Gärling. 2008. The relationships between awareness of consequences, environmental concern, and value orientations. Journal of Environmental Psychology 28: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, Anita, Johanna Wyn, and Salem Younes. 2010. Beyond apathetic or activist youth: ‘Ordinary’ young people and contemporary forms of participation. Young 18: 9–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungerford, Harold R., and Trudi L. Volk. 1990. Changing learner behavior through environmental education. The Journal of Environmental Education 21: 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Fanli, Susan Alisat, Kendall Soucie, and Michael Pratt. 2015. Generative concern and environmentalism: A mixed methods longitudinal study of emerging and young adults. Emerging Adulthood 3: 306–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Fanli, Kendall Soucie, Susan Alisat, Daniel Curtin, and Michael Pratt. 2017. Are environmental issues moral issues? Moral identity in relation to protecting the natural world. Journal of Environmental Psychology 52: 104–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, Terry, Ian Mason, M. Leiss, and S. Ganesh. 2006. University community responses to on-campus resource recycling. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 47: 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, Emily Huddart, Thomas M. Beckley, Bonita L. McFarlane, and Solange Nadeau. 2009. Why we don’t “walk the talk”: Understanding the environmental values/behaviour gap in Canada. Human Ecology Review 16: 151–60. [Google Scholar]

- Kollmuss, Anja, and Julian Agyeman. 2002. Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environmental Education Research 8: 239–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, Kenneth Brandon. 2011. The relationship between academic major and environmentalism among college students: Is it mediated by the effects of gender, political ideology and financial security? The Journal of Environmental Education 42: 203–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Yong-ki, Sally Kim, Min-seong Kim, and Jeang-gu Choi. 2014. Antecedents and interrelationships of three types of pro-environmental behavior. Journal of Business Research 67: 2097–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, Arthur, and Deborah Hirsch. 1991. Undergraduates in transition: A new wave of activism on American college campus. Higher Education 22: 119–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, Debra Siegel, and Michael J. Strube. 2012. Environmental attitudes, knowledge, intentions and behaviors among college students. The Journal of Social Psychology 152: 308–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Danqing, and Jin Chen. 2015. Significant life experiences on the formation of environmental action among Chinese college students. Environmental Education Research 21: 612–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, Peter C. 2009. Negotiating community engagement and science in the federal environmental public health sector. Medical Anthropology Quarterly 23: 94–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubell, Mark. 2002. Environmental activism as collective action. Environment and Behavior 34: 431–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubell, Mark, Sammy Zahran, and Arnold Vedlitz. 2007. Collective action and citizen responses to global warming. Political Behavior 29: 391–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquart-Pyatt, Sandra T. 2012. Explaining environmental activism across countries. Society & Natural Resources 25: 683–99. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuba, Kyle, Susan Alisat, and Michael W. Pratt. 2017. Environmental Activism in Emerging Adulthood. In Flourishing in Emerging Adulthood: Positive Development During the Third Decade of Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 175. [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane, Bonita L., and Len M. Hunt. 2006. Environmental Activism in the Forest Sector Social Psychological, Social-Cultural, and Contextual Effects. Environment and Behavior 38: 266–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ménard, Marion. 2010. Youth Civic Engagement. Parliamentary Information and Research Service. Social Affairs Division. Ottawa: Library of Parliament. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, Michael Quinn. 2005. Qualitative Research. Wiley Online Library. [Google Scholar]

- Quintelier, Ellen. 2008. Who is politically active: The athlete, the scout member or the environmental activist? Young people, voluntary engagement and political participation. Acta Sociologica 51: 355–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reysen, Stephen, and Justin Hackett. 2017. Activism as a pathway to global citizenship. The Social Science Journal 54: 132–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SGuin, Chantal, Luc G. Pelletier, and John Hunsley. 1998. Toward a model of environmental activism. Environment and Behavior 30: 628–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherrod, Lonnie R. 2006. Promoting citizenship and activism in today’s youth. In Beyond Resistance. New York and London: Routledge, chp. 17. pp. 287–99. [Google Scholar]

- Sivek, Daniel J. 2002. Environmental sensitivity among Wisconsin high school students. Environmental Education Research 8: 155–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tindall, D. B., Scott Davies, and Céline Mauboules. 2003. Activism and conservation behavior in an environmental movement: The contradictory effects of gender. Society & Natural Resources 16: 909–32. [Google Scholar]

- Torney-Purta, Judith. 2002. The school’s role in developing civic engagement: A study of adolescents in twenty-eight countries. Applied Developmental Science 6: 203–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, Jean M., W. Keith Campbell, and Elise C. Freeman. 2012. Generational Differences in Young Adults’ Life Goals, Concern for Others, and Civic Orientation, 1966–2009. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 102: 1045–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicente-Molina, María Azucena, Ana Fernández-Sáinz, and Julen Izagirre-Olaizola. 2013. Environmental knowledge and other variables affecting pro-environmental behaviour: Comparison of university students from emerging and advanced countries. Journal of Cleaner Production 61: 130–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukelic, Jelisaveta, and Dragan Stanojevic. 2012. Environmental activism as a new form of political participation of the youth in Serbia. Sociologija 54: 387–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Research Question | Code | Code Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Main RQ: What reasons do self-identified environmentalists or activists give for taking action against environmental problems that concern them? That is, what is their motivation? | EXPERIENCE | One’s previous experiences and education (can be formal education, learning on one’s own, learning from others, indirect education) that influence one’s desire (or lack thereof) to participate in activism |

| AWARENESS | Being made or making others aware of an issue, idea, concept, problem, etc., by any method (talking to someone, reading, education, etc.) | |

| SELF-IMPROVEMENT | Doing something because of a desire to improve one’s own life/character or to further one’s self-interest | |

| PASSION | Doing something because of a connection with that subject and/or because of one’s passion for that subject | |

| INCENTIVES | Having an external (that is, outwardly-motivated) reason to do something. Usually this involves getting something in return, but that is not a necessary condition to be met | |

| PWYP | The desire to take action against a concern to “be the change you want to see” | |

| COMMUNITY | The desire to do something in order to improve or become engaged with a community, or to get the community involved in one’s cause | |

| Sub RQs: What prevents or discourages self-identified environmentalists (SIEs) from taking action on their concerns (environmental or otherwise)? That is, what thresholds or barriers, if any, exist for taking action? Why? | INVOLVEMENT | The perception of being easily able to become involved with a group, project, campaign, etc. |

| TIME | Having or not having enough time to become involved in something, or to do something, related to one’s activistic concerns |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fung, C.Y.; Adams, E.A. What Motivates Student Environmental Activists on College Campuses? An In-Depth Qualitative Study. Soc. Sci. 2017, 6, 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci6040134

Fung CY, Adams EA. What Motivates Student Environmental Activists on College Campuses? An In-Depth Qualitative Study. Social Sciences. 2017; 6(4):134. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci6040134

Chicago/Turabian StyleFung, Cadi Y., and Ellis Adjei Adams. 2017. "What Motivates Student Environmental Activists on College Campuses? An In-Depth Qualitative Study" Social Sciences 6, no. 4: 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci6040134

APA StyleFung, C. Y., & Adams, E. A. (2017). What Motivates Student Environmental Activists on College Campuses? An In-Depth Qualitative Study. Social Sciences, 6(4), 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci6040134