1. Introduction

In the online dating realm, niche is key. From VeggieDate.org for vegetarians to DateGinger.com for redheads, online dating companies are setting their sights on increasingly specific segments of the population with niche websites that profess to facilitate romantic connections based on shared user characteristics. Even mainstream dating services that aim for broader audiences, such as eHarmony and Match.com, now feature specialized sections for various subgroups of users based on race, religion, and other distinctive qualities. Mark Brooks, dating industry consultant and editor of OnlinePersonalsWatch.com, estimates that about 44 percent of all dating sites in the U.S. are niche sites [

1]. Brooks explains this trend as an appeal to users’ desires for targeted services, stating, “It’s the same reason why Procter & Gamble makes so many detergents. We are all drawn to things that cater to our very specific desires” [

1].

In order to achieve this kind of niche targeting, online dating companies must engage in a process of audience construction, deciding whom they wish to target and how to do so most effectively. However, as media scholar Ien Ang explains, the construction of audiences is a highly subjective process. She describes the media audience as “an imaginary entity, an abstraction constructed from the vantage point of institutions, in the interest of institutions” ([

2], p. 2). In other words, media audiences are not naturally occurring collectives. Instead, they are carefully crafted by the media industries in an effort to advance their own goals and objectives. In many cases, industry leaders are driven less by the desire to meet the needs of their target audiences and more by the incentive to translate those needs into a financial profit. With this in mind, it is important to investigate how industry executives construct audiences in the online dating arena and what implications their strategies might have on the growing number of people joining these sites. To date, online dating research has focused primarily on mainstream dating sites (see [

3,

4] for examples), leaving niche services largely overlooked. This project hones in on one niche dating market in particular—the increasingly popular “older adult” market—in an effort to more closely examine the process of audience construction and niche targeting in the online dating industry.

4. Results

After a thorough examination of the selected sites, I identified three key patterns regarding niche targeting in the older-adult online dating market: (1) the use of mass segmentation, a strategy that combines elements of both mass marketing and market segmentation; (2) strategic attempts to broaden the boundaries of their niche audiences; and (3) the use of deceptive advertising to appeal to older adults users. These findings, further elaborated below, suggest that older-adult online dating sites are, in fact, engaging in pseudo-individualization. They also reveal some of the specific techniques these niche services use to achieve the illusion of specialization.

4.1. Mass Segmentation

One of the first major findings to emerge in this study was that many of the older-adult dating services analyzed were part of a larger effort by online dating companies to cater to several niches at once. Rather than focusing on older adults alone, the companies that operated these sites were involved in a number of other niche services targeted at a wide variety of niche communities. After examining these patterns, each of the older-adult dating sites in this study fell into one of two categories: (1) niche networks and (2) niche branches of mainstream services. Here, I define a niche network as a group of niche dating sites that are owned and operated by the same parent company. Seven of the 10 older-adult sites in this study fell into this category

2. The range of audiences targeted within a niche network were often quite diverse; for example, SuccessfulMatch, the company that operates SeniorMatch.com, also hosts matchmaking sites for single parents, bisexuals, Muslims, Goths, and the deaf. A similar approach was observed with sites of the second category—niche branches of mainstream services. As stated earlier, mainstream dating services like Match.com have begun to capitalize on the popularity of niche sites by creating specialized offerings of their own, housed under the larger umbrella of the primary company. Three of the 10 older-adult sites in this study fell into this category

3, while 4 of the 10 sites in the mainstream sample also contained niche subsites

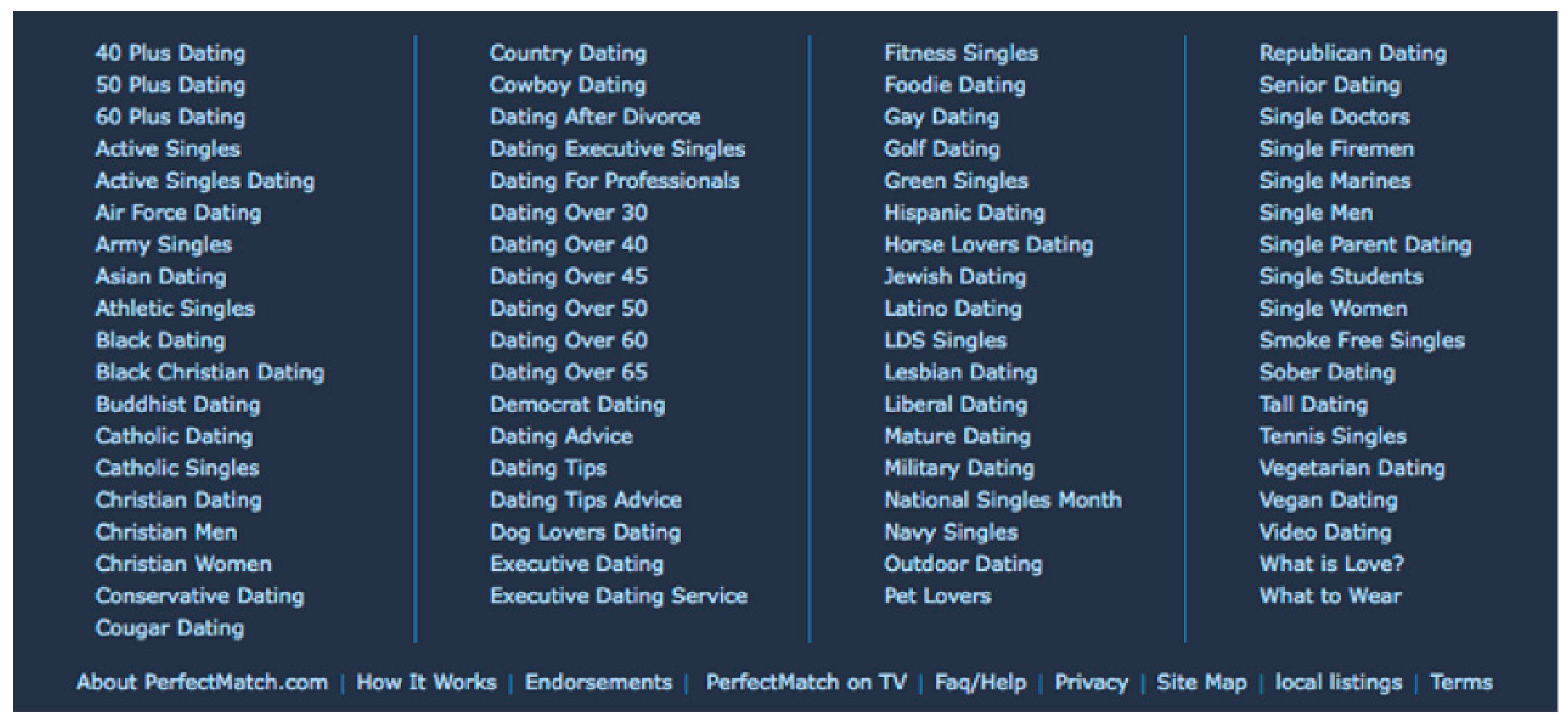

4. Sites in this group covered an equally diverse range of niche audiences (see

Figure 1 for example).

For both niche networks and niche branches of mainstream dating services, the goal seemed to be to capture as many niche markets as possible. In fact, the website for First Beat Media, parent company of Dating for Seniors, openly proclaimed, “There isn’t a dating niche we won’t tap into” [

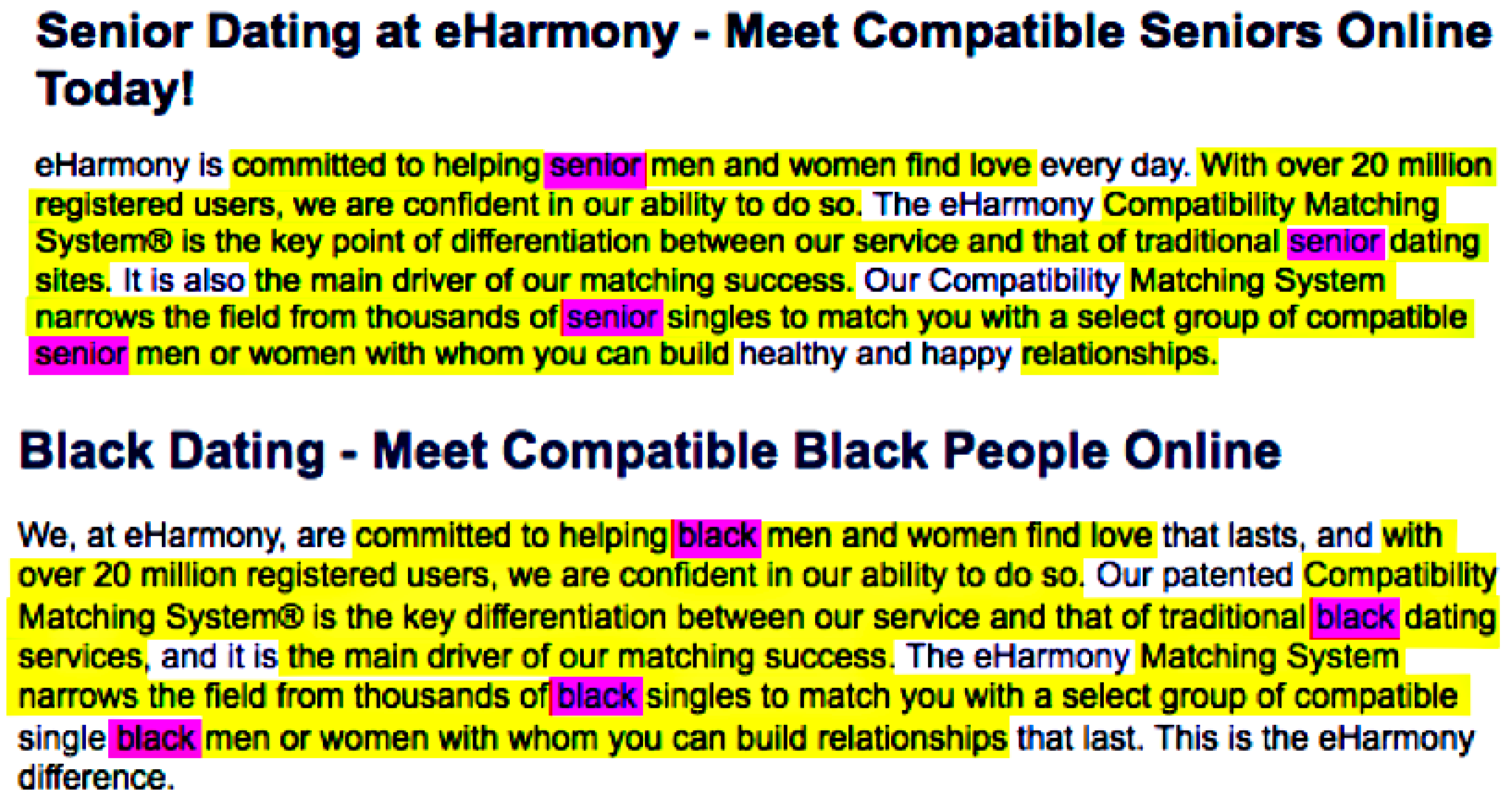

34]. Yet, in taking this approach, these sites often deployed fairly shallow appeals to their audiences, relying primarily on standardized layouts with easily substitutable text and visuals designed to signal in-group identity. Many of these dating services adopted a template approach to site design, applying the same basic structure to all of their niche sites and simply plugging in information about the target group wherever applicable. On one level, these online dating companies have divided the general population into niche subgroups and created different sites that target each group (market segmentation); however, because their products—the sites themselves—are often derived from the same standardized formulas, and those formulas are used to appeal to a broad and diverse range of people (mass marketing), I have coined the term mass segmentation to describe this approach. Consider

Figure 2 below, a comparison of site descriptions from eHarmony’s Senior Dating page and their Black Dating page:

As the highlighted portions emphasize, the bulk of these two texts is nearly identical, with the name of the target group merely being plugged in at the appropriate places

5. Yet, looking at either of these sites in isolation, visitors are less apt to realize that what they are reading is actually a standardized appeal used across a variety of audiences. Thus, much like Turow’s example of the radio listeners who thought they were receiving personal response letters written specifically to them when, in fact, it was “just a standard reply” ([

28], p. 541), users of the niche dating sites outlined above may think they are joining (in many cases, even paying for) a service tailored just for them, unaware that the promise of specialization is mostly a recruitment tool.

4.2. Broadening the Niche

In addition to the broad net these services cast externally through mass segmentation—reaching beyond the older-adult niche in an effort to capture a wide range of other audiences—many of them also cast a broad net internally through the ways they defined the older-adult niche. As stated earlier, online dating companies have come up with a variety of terms for referring to the older-adult audience, one of the most widely used being the term “senior”. In fact, of the 10 older-adult dating sites analyzed in this study, six include “senior” as part of their company name. In common parlance, the term “senior”, when it appears in this context, is short for “senior citizen”, a euphemistic label used to refer to people past a certain age. Although there is no official qualifying age for senior citizenship, perhaps the most universally recognized measure is the legal retirement age, which ranges from 65–67 in the U.S., depending on birth year [

37]. While the “senior” label was used by several of the older-adult dating sites in this study, the boundaries used to define this group seemed to vary from site to site, and all were significantly lower than the legal retirement mark of 65. Of the sites in the sample that explicitly stated a target age group

6, the most common target age range was 50 and older—a full 15 years below the traditional 65. In addition, both Senior Friend Finder and MatureSinglesClick identified their target audience as people over 40, yet still referred to their users as “seniors”.

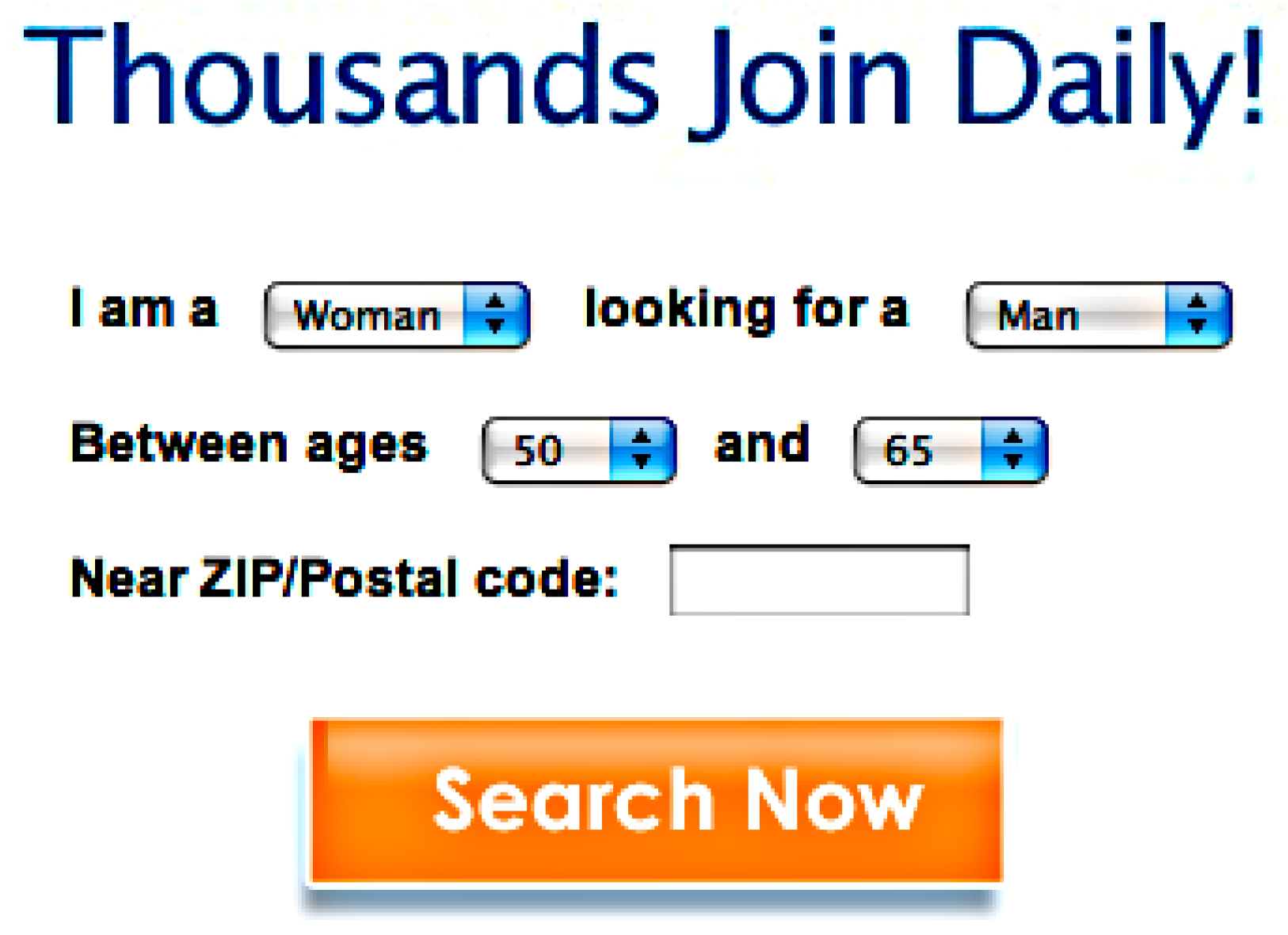

The use of an explicitly stated target age range was not the only indicator of target audience on these sites. The homepages on most of the older-adult sites in this study also featured a “quick browse” section where visitors could enter a few of the basic criteria they were seeking in a partner, including age range, in order to browse the site for potential matches (see

Figure 3 for example).

While users had the option to adjust this age range manually, it started out at a company-defined default, which also varied from site to site. The fact that the default range varied across sites highlights the fact that the developers of each site had to make a conscious decision about what this range would be; thus, I would argue that the age range they chose to display served as an implicit way of signaling their target audience. Interestingly, three of the six sites that included this feature had a default lower age limit of 40 years old, including SeniorMatch.com, whose stated target range was 50 and up. This further demonstrates the loosely defined approach to targeting utilized by many of these sites. SeniorPeopleMeet even expanded their target age range during the course of this study. Between October and December of 2011, the site updated its homepage, and as part of this update, added the tagline “#1 dating community for 50+ singles” underneath the company logo. Before making this change, there was no such indicator of target age range on the site’s homepage; however, the “About” section of the website stated in multiple places that the service was intended for singles over 55 (in fact, the “About” page remains unchanged at the time of this writing). Although there has been no official statement from SeniorPeopleMeet explaining this shift in target from 55 to 50, it seems to reflect a larger pattern among online dating sites of defining the older-adult niche in increasingly broad terms.

In addition to this broad definition of the intended audience, the older-adult dating sites analyzed in this study also contained few barriers to entry for people outside the target group. As Turow argues, “Urging people who do not fit the desired lifestyle profile not to be part of the audience is sometimes also an aim [of consumer targeting] since it makes the community more pure and thereby more efficient for advertisers” ([

13], p. 5, italics in original), yet this deterrent form of signaling was relatively scarce among the niche sites in this study. For example, in the aforementioned quick browse section of these sites, the desired age range was typically indicated by two drop-down menus—one for minimum age and one for maximum age. In addition to the upper and lower default age limits discussed earlier, each site also featured a lowest possible and highest possible age from which users could choose. With regards to the lowest possible age, 8 of the 10 older-adult sites included search parameters that went as low as 18 years of age. The two remaining sites, lavalifePRIME and SeniorMatch.com, still set their lower age cutoffs far below 65, at 40 and 30, respectively. In another example, the registration page on SeniorMatch.com included a required checkbox, which stated, “I am 30+ and have read and agree to the Service Agreement and Privacy Policy” (see

Figure 4). Because checking this box was a mandatory part of registration, it was apparently designed to create a minimum age requirement for the site and should, in theory, serve to ward off younger users; however, it must again be noted that SeniorMatch.com’s stated target age group was 50 and over, making this cutoff at age 30 inconsistent with the supposed target market. Further, no other sites in the sample included this kind of gatekeeping feature.

This pattern of broadening the niche is relevant to this study because it has the potential to shift the membership of these sites away from their niche origins. While the primary goal of niche targeting is to narrow the mass population into smaller and more precisely defined subsets, the observations detailed in this section suggest that older-adult dating sites seemed to be more inclusive than exclusive in the ways they defined their target audiences and structured their online interfaces. Further, these sites often sent mixed message about whom their target was, whether through their loose application of the label “senior” or through inconsistencies within sites regarding target age range. Ultimately, it appears that the niche sites in this sample are interested in keeping the older adult niche as broad as possible, which raises some important questions: (1) To what extent can these services be considered truly niche? If age is their defining characteristic, yet they continue to embrace younger users, these sites may soon lose their niche quality and become mainstream; (2) Why have so many of these services adopted this approach? One could speculate that the goal is to maximize subscribership, but perhaps there are other factors at play; and finally; (3) How does this broad conceptualization of the audience affect their ability to customize their services to accommodate their users? This third question will be addressed, in part, in the following section.

4.3. Deceptive Advertising

As stated earlier, the shift toward niche services was inspired in part by the growing consumer demand for personalized, customized consumption choices. Yet, while many of the niche sites in this study claimed to offer services that were specialized and tailored for the older-adult population, evidence of actual differentiation was, for the most part, lacking. To substantiate this point, it must first be established that the mainstream dating sites in this study often made fairly specific claims about the competitive advantage(s) of their services. eHarmony, for example, actively promoted its trademarked “29 Dimensions of Compatibility” matching system throughout the site, including a dedicated webpage that explained this system in detail [

40]. OkCupid provided a similar, even more extensive, explanation of its unique matching system [

41]. Other mainstream sites touted on-site relationship experts (e.g., Dr. Pepper Schwartz at Perfectmatch.com), patented personality tests (see Chemistry.com), and other offerings that were exclusive to their service to help potential customers distinguish them from their competitors. On the other hand, older adult dating sites made claims of uniqueness in ways that were much more vague. For example, the OurTime.com website stated:

At OurTime.com, we honor the freedom, wisdom and appreciation for life that only comes with time. We also recognize that what people want in their 50s, 60s and beyond is often very different from what they wanted in their 30s and 40s, let alone their 20s. This online dating community focuses on the specific interests and desires of people like you.

With the excerpt above, OurTime claims to understand the distinct needs of their target population; however, upon further investigation, I found that the site was consistently ambiguous as to what these needs actually were and how their service went about meeting them. Similarly, SeniorPeopleMeet.com described itself as “a community specially designed to cater to senior singles seeking mature dating” and encouraged visitors to “look beyond…generic online dating sites” [

43], yet never made clear the strategies they were using to “cater” to their audience and separate themselves from their “generic” mainstream competitors. According to Hsieh, Hsu, and Fang, this approach could be seen as a form of deceptive advertising [

44]. Citing Carlson, Grove, and Kangun’s typology of deceptive claims [

45], the authors identify the vague/ambiguous claim as one that is “so equivocal that the audience is unable to discern the specific purport of the claim. In other words, it contains expressions or assertions that are too ambiguous to have a manifest meaning” ([

44], p. 5). Such ambiguity could ultimately be misleading to prospective online dating users, as it may promote false expectations of what the site is actually able to offer. For example, one key area where one might expect niche sites like OurTime or SeniorPeopleMeet to differ from mainstream sites would be in how their user profiles—arguably the cornerstone of the online dating experience—are structured; however, comparisons revealed minimal differences between the profile structures of older adult sites and mainstream sites, especially in ways that suggested any meaningful attempts at age-specific tailoring. Instead, the strategy taken by most of these sites seemed to be one of signaling without tailoring. In other words, the older adult sites in this study attempted to attract their target audience by incorporating the elements necessary to show visitors that a site was created especially for seniors (most notably with visual cues conveyed through photos); yet, in the end, they seemed to rely on the same standardized techniques for matchmaking that are utilized throughout the online dating realm

7.

Not only did the older-adult dating sites in this study seem to lack the kind of age-specific tailoring that would make them meaningfully different from mainstream dating sites, but in several cases, they failed to fulfill even the most basic expectation of a niche service—an exclusive, homogeneous dating pool. To reiterate an earlier point, one of the perceived benefits of choosing a niche dating site over a mainstream site is that it places the user into a comparatively smaller pool of potential partners, all of whom share something in common. Unfortunately, I discovered multiple examples where the smaller, more homogeneous community one might expect from an older adult dating site was simply not being provided. For example, near the bottom of eHarmony’s Senior Dating page the site explained, “If you would like to date senior women or senior men specifically, make sure to adjust your criteria to reflect this preference” [

35]. Simply put, this was a roundabout way of saying that registering for an account on eHarmony Senior Dating was no different than registering for eHarmony’s main site, and that the onus was on the user to narrow the pool down to the senior age group. This interpretation was easily verified in that the same username and password could be used for both sites, and both provided access to the same pool of potential partners. Thus, by placing users into a large, heterogeneous dating pool and essentially telling them to fend for themselves with regard to age tailoring, eHarmony’s Senior Dating service offers the complete opposite of a niche dating experience, yet those that do not read (or fully understand) this statement might easily be misled into signing up for an account believing otherwise.

The example described above, in which eHarmony’s Senior Dating signals one thing through its marketing but offers users something entirely different, comes dangerously close to another form of deceptive advertising—the bait-and-switch. Yet eHarmony was not the only company to employ this strategy, as an even more problematic example of this approach was discovered on the site MatureSinglesClick. Not only did this site signal to older adults through its name and branding, but it went a step further by making explicit claims about how it tailored to this audience. Their homepage plainly read, “As the online dating destination for senior singles, MatureSinglesClick is tailored to meet the dating needs of mature singles worldwide” [

46]. Not only was this another example of a vague/ambiguous claim that was never fully explicated, but a closer look revealed that this site was actually a subsidiary of the mainstream dating site Date.com and that MatureSinglesClick users were being discreetly rerouted into the Date.com dating pool. Additionally, Date.com login information could actually be used to log in to MatureSinglesClick

8. Surprisingly, the fine-print disclaimers seen on sites like the eHarmony Senior Dating page were totally absent from MatureSinglesClick—the connection to Date.com was discovered purely by accident

9. Further, the structural features of MatureSinglesClick appeared to be indistinguishable from the larger Date.com site with the exception of the logo in the upper left-hand corner. In short, it appeared that MatureSinglesClick and Date.com were, functionally speaking, the same service. Unless users approach these sites with heightened attention to detail and engage in the kinds of side-by-side comparisons I participated in as a researcher, the kinds of observations noted in this section are likely to go unnoticed. Moreover, the likelihood that sites like these that, in some cases, are not even providing a niche dating pool itself are putting in the effort needed to offer users a truly tailored experience seems highly doubtful.

5. Discussion

The primary goal of this study was to shed new light on the use of niche marketing strategies in the online dating realm. By focusing on the older adult market, one of the most sought-after niches in the industry today, this study looked to unpack the segmentation processes used by older-adult dating sites to attract and cater to the older adult population. In the process, I also set out to test Fiore’s theory that most niche dating sites lack specialized system designs, relying instead on more superficial forms of customization [

25].

One important contribution of this study is its introduction of the concept mass segmentation, an approach that combines aspects of both mass marketing and market segmentation. Despite lacking a term for it at the time, Danielle Kurtzleben of U.S. News & World Report describes the benefits of this approach in a 2013 article, stating, “Many successful niche sites are run by large companies. One company might run dozens of sites, making cross-advertising and site maintenance for all of those sites much simpler than if all of them were run independently” [

19]. With the replicability and reach of digital media [

47], once the template for a niche dating site has been developed, the ease with which a company can create derivative sites aimed at other niches and distribute these sites across the web opens up a world of opportunities for appealing to niche populations with minimal effort. In addition, the ability to attract a wide range of increasingly specific niche audiences allows these companies to offer advertisers better opportunities for consumer targeting. With niche sites, users are automatically divided into neatly organized groups that mirror many of the demographic and lifestyle groups sought by advertisers, and by filling out online dating profiles, users are offering up a wealth of data that the ad industry considers highly valuable. A 2009 media kit from PeopleMedia, operator of SeniorPeopleMeet, highlights this point with a full page dedicated to the hypertargeting possibilities available through their niche dating network [

48]. Thus, motives for niche marketing in the online dating realm are much more complicated than simply meeting the needs of users. The ability to maximize subscription revenue (for paid sites) and convert one’s user base into saleable advertising dollars appears to play an equally important—if not more important—role in this process. While on the surface mass segmentation may seem both benign and fairly justifiable, it exploits the audience’s desire for specialized services and uses the appearance of specialization as a recruitment tool. In many of the examples in this study it appears to be little more than a thinly veiled attempt at pseudo-individualization—making the audience feel like they were being catered to when in reality they were not. One of the major criticisms of the mass marketing approach is that it treats a heterogeneous population as though it were homogeneous [

21]; yet, by using a universal template to create an array of niche sites, mass segmentation does just that. In short, because mass segmentation is standardization disguised as segmentation, it is, by definition, pseudo-individualization.

This study also revealed that, on the whole, operators of older-adult dating sites seem to be making a conscious effort at broadening their desired niche to include more and more “outsiders” from the younger population. Not only did these sites have a tendency to stretch the boundaries of terms like “senior” beyond their conventional limits, but their content was infused with explicit and implicit messages designed to attract a younger audience. Most likely, these attempts at broadening the target market are at least partially motivated by the tension these sites face between being specialized enough to be considered niche while at the same time being able to attract enough subscribers to offer a quality online dating experience. As Carpenter explains, “Ultimately, the success of any site depends on the number of people using it. The greater the number, the greater the odds of finding a good match” [

10]. This is commonly referred to as a network effect, in which the value of a good or service is contingent upon the number of people who use it [

49]. Without a “critical mass” of users, an interactive medium loses its utility, and the likelihood of its success is greatly diminished [

50]. Older-adult dating sites face the added challenge of obtaining a balanced user base since, statistically, single women begin to significantly outnumber single men beyond the age of 65 [

51]. Furthermore, men’s tendency to prefer younger partners combined with women’s tendency to prefer older ones may lead to a skewing of the dating pool on senior sites [

52]. In fact, it appears that SeniorPeopleMeet may have already struggled with this problem, as the site’s users were reportedly 81 percent female in 2007 [

53]. By broadening the target audience, older adult dating sites may be able to better overcome some of these issues; however, they also send a mixed message in the process—marketing themselves as being for “seniors”, yet courting users that are much younger. Confronted with this seeming contradiction, I was forced to ask myself, “When did 40 become the new 65?” More importantly, once the older-adult niche is broadened past a certain point, is it really a niche at all? Not only does this practice erase the niche quality of the online dating pool, but as the user bases for these sites become less homogeneous, it becomes increasingly difficult for developers to offer precise tailoring to their originally intended audience. In this way, Fiore’s suggestion that niche specialization in the online dating realm is often inauthentic appears to hold true [

25].

In the end, the potential challenges of tailoring to an ever-broadening niche may be of minimal concern to older-adult dating services because for many of the older adult sites in this study, the claim of age-specific customization appears to be an empty promise. After closely inspecting the selected sample of older-adult dating sites and comparing them against their mainstream peers, not only did I find little evidence of actual differentiation on the niche sites, but in several cases, these niche services appeared to be engaged in various forms of deceptive advertising. In some cases, this deception took the form of vague/ambiguous claims [

44] in which services like OurTime and SeniorPeopleMeet described their specialized features in such equivocal language that they ultimately provided little concrete understanding of how these sites actually achieved such specialization. This stood in stark contrast to the mainstream dating world in which eHarmony, OkCupid, and others provided in-depth explanations of their matchmaking processes and other unique features. Elsewhere, some older-adult dating sites engaged in deceptive advertising through the use of a bait-and-switch style strategy, in which they marketed themselves as niche targeted services, yet upon registration, users were discreetly rerouted into large and heterogeneous dating pools. I argue that this practice is highly misleading, as these sites are essentially selling one thing while providing something entirely different. Again, this points back to the work of Adorno [

26], as much of the customization these sites claim to provide appears to be little more than pseudo-individualization.

Taken together, the results of this study seem to confirm Fiore’s suspicion that the specialization offered by niche dating sites operates at a mostly superficial level [

25]. Rather than providing a genuinely tailored experience to older online daters, the niche sites in this study seemed to rely on conspicuous signaling strategies that sought to lure this population in by giving off what was often a false impression of customization. That being the case, another major contributions of this study is the extension of Adorno’s notion of pseudo-individualization into new conceptual territory [

26]. The online medium has created an environment in which making content appear to be customized is cheaper and easier than ever before. Online dating services (and other web companies for that matter) can capitalize on this situation by making virtually everyone feel catered to through a myriad of niche appeals. As a result, these companies can broaden their user base by pretending to narrow it. Because the details of pseudo-individualization discussed in this paper are likely to go unnoticed by most casual users, producers are still able to reap the benefits of actual tailoring but with much less effort.

In reflecting on the findings of this study, there are a number of additional questions to consider in order to push this research forward. First, a follow-up study that looks at the makeup of actual users that subscribe to the older adult sites mentioned in this study would be highly beneficial. In particular, it is unclear whether these services’ efforts to broaden the niche of their target audience have been successful. Opening up to younger users does not necessarily mean that younger users will willingly join these sites, so further investigation could help to shed light on whether they have managed to maintain their niche quality. In addition, it would be useful to interview executives from online dating companies, especially niche networks, to find out how exactly they go about both selecting and catering to their intended audiences. Perhaps there are certain processes at work that are simply not detectable through the approaches used in this study, so the direct questioning of industry insiders could be used to help to verify these findings. In a similar vein, future studies should also examine how the observations in this study compare to niche dating sites aimed at other specialized audiences. While this study uses the older-adult market as a case study of niche marketing in the online dating realm, its findings may not always apply to other niche audiences. For example, sites like JDate, a Jewish dating service that engages in some fairly obvious forms of customization—including a number of profile items that are uniquely Jewish—would clearly not fit into the framework presented here. Another important question that may help put the current study’s findings into their appropriate context is, “What are the unique needs of the older-adult population with regard to dating and romance?” To again quote from OurTime.com, the site proudly proclaims

We also recognize that what people want in their 50s, 60s and beyond is often very different from what they wanted in their 30s and 40s, let alone their 20s. This online dating community focuses on the specific interests and desires of people like you.

Yet, the company never fully elaborates on what these important differences in interest and desire are. One way to address this question would be to conduct studies on what older adults want from online dating and how these wants compare to the broader population. Perhaps the need for a tailored online dating experience for older adults is a manufactured one, designed by the industry to attract subscribers. It may be the case that with the older adult population there are simply not enough clear opportunities for specialization with regards to dating and matchmaking to tailor these sites accordingly. It may also be true that the primary form of specialization desired by older adults is a system that makes finding other older adults easier—a homogeneous dating pool. Earlier in this paper, I accused older-adult dating companies of “signaling without tailoring”, but if the majority of users are merely seeking a dating pool of people in their age bracket, then perhaps basic signaling is all that is needed. Finally, at the heart of this study is the notion that media nichification is, in large part, driven by the desire to attract advertisers, but little has been done to explore the relationship between online dating companies and advertisers. A closer look at the ways dating sites interact with the advertising system, including when and how they host ads and the extent to which they share user data with advertisers, could help to provide a fuller picture of the issues presented here.