1. Introduction

In announcing a “Year of Inquiry” during the academic year of 2014–2015, the Dean of the College of Education and Human Sciences (EHS) created a call to action that encouraged faculty members to actively explore something that sparked their curiosity. Since several faculty members had expressed curiosity about Reggio-Inspired practices and the work of the Educational Project of Reggio Emilia, Italy, they decided to learn more about that philosophy. In response to this interest and the call to action, Kay Cutler offered to lead a book discussion over the

Hundred Languages of Children: The Reggio Experience in Transformation [

1]. Previously, she and others from the Children’s Museum of South Dakota had studied the book, concluding that the book should be read and discussed by a larger cross-section of community residents, including university students, as a provocation. In this way, they meant to stimulate a thought process in Brookings.

The book focuses on the city of Reggio Emilia’s educational system; however, the civic community, community members and families are also involved in the governance and leadership of the city-owned schools. In this Italian setting, children are viewed as the city’s youngest citizens and as contributing members to their community. In addition, the culture has an embedded, systemic concept of child and family well-being [

1]. Often, the published works of Reggio Emilia and nearby cities, such as Pistoia, Italy, focus on the educational components, yet the concept of individual and group well-being is very intricately woven into experiences for young children and families.

The book study offered in the fall of 2014 attracted a cross-section of 15 community/university individuals, including Early Childhood Education faculty members, a Teacher Education faculty member, an Interior Design faculty member, administrators and staff from the Children’s Museum of South Dakota, the South Dakota Art Museum Director, a college student, the Dean of the College of EHS, a business entrepreneur and two directors of a local daycare. Using an initial provocation of “Let’s consider what we can do here, in Brookings, as we read about the work in Reggio Emilia, Italy”, the group met every month and engaged in lively discussions. A chapter written by the mayor of this city at that time sparked a detailed group discussion about the similarities and differences between Reggio Emilia and Brookings. As they read about the organization of the educational office, agency and schools or center through parental representation on the City Education Council, the group’s positive energy was palpable. During this particular conversation, they decided to hold a separate meeting outside the regular book study time to capture these newly-recognized thoughts regarding family and child well-being and the process of raising it as a topic for a community-wide conversation.

3. Child and Family Well-Being

Child well-being and family well-being can be viewed as two separate constructs, yet family well-being factors often shape the nature of children’s well-being factors, and children’s well-being factors should be considered in terms of the familial and community context [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Some familial factors that may influence child well-being include socio-economic status [

9,

10], parental education levels [

11], marital stability [

12,

13,

14], religious health as measured by participating in religious experiences as a buffer for stress [

15,

16,

17] and connectedness to a support network [

18].

Cultural influences often determine how a group of individuals define well-being, either child or family. For example, the Italian culture views well-being as a group construct defined [

19] Donatella Giovanni and measured by context, the environmental stability and relational characteristics [

19]. Semanchin Jones, LaLiberte and Piescher find that many models include individual variables focusing on social, physical, cognitive and emotional well-being when looking at child well-being [

20,

21]. They also find that a few models include contextual, familial aspects or concepts about stability and permanency when coming from a cultural group. Examples include the Relational Worldview Framework created by the National Indian Welfare Association [

22] or a more complete viewpoint from the University of Minnesota Center for Spirituality and Healing Model [

23]. These two models seem to bring together the being and the context to a greater extent, thus providing a more holistic view of child well-being.

In the Reggio Emilia-inspired practices of Pistoia, Italy, the citizens have engaged in an ongoing dynamic dialogue about what it means to be a child-friendly city. They have created an action plan that involved building places to give children a sense of belonging throughout the city via spaces, signage indicating child-friendly businesses and city policies that ensure more safe urban space for learning and being [

24].

Other places around the world have also begun to civically engage in studying children’s well-being, such as Melbourne, Australia, as noted in their Kids in Community Report about their city’s state of children’s well-being [

25]. Some cities, also inspired by the work of Reggio Emilia, are working to build capacity to become more civically-engaged communities. For example, Tacoma, Washington, actively seeks to build more opportunities and services on its way to becoming a more child-friendly city [

26]. They hosted a one-day conference to ask, “What if children were at the heart of our city?”, “What if children came up with community solutions?” and “What if Tacoma were a great place to be a child?” ([

26], pp. 5–6). “How would our city look if children helped to solve our community problems? What if families have support and resources before they knew they needed it? What if we did stuff with children instead of for children?” ([

27], para. 1).

In pursuing these goals, groups have utilized a variety of methodologies and collected multiple types of data to investigate the status quo and to establish a baseline for improvement. The process of data collection can drive the efforts as citizens seek to understand and to capture the complexities of community. Using multiple measures ensures multiple perspectives, as illustrated in the following list of methodologies from an Australian study that used community surveys, focus groups, stakeholder interviews, service counts, evaluations of access to services, geographical mapping, neighborhood observations, walkability audits and the analysis of census data [

25].

After discussing the Melbourne, Australia, report [

25] and a local report, the BSC’s Benchmarks document [

28], the Brookings CoP determined to collect its own data regarding child and family well-being. Maintaining their inquiry-based approach, they also wondered, “How can we civically engage the citizens in our community of Brookings, South Dakota, to dialogue about child and family well-being?” This paper describes how a CoP sought to answer this question. While the journey is by no means complete, the following narrative explains a grassroots process that laid the foundation for ongoing civic engagement.

First, to establish a baseline in Brookings, the CoP began to gather and discuss data from its own community, which put the members in contact with local government and city leaders. One specific study, developed by the Brookings Sustainability Council (BSC) and detailed below in its Benchmarks document, gathered local data to compare Brookings to five “sister” regional cities [

28]. As the next step to move the CoP forward and to seek a more official home, the group introduced themselves to the Brookings mayor and requested a meeting.

3.1. Meeting with the Brookings, South Dakota, Mayor

After explaining the origin of the CoP in the book study group, the CoP presented the mayor with a copy of the

Hundred Languages of Children [

1] and gave an overview of its progress to date. They discussed ways the CoP could benefit the city and if it were possible to find a home in the city organizational structure, if the group became more formalized. The mayor encouraged them to review the city policies through the lens of child and family well-being, to identify further data gaps and to ask for time on the BSC’s agenda so they would know of this group’s existence. He suggested that the BSC would be the best match for this work in the organizational structure of the city.

3.2. Meeting with the Brookings Sustainability Council

Based on the mayor’s suggestion, CoP members met with the BSC. At this full council meeting, they briefly described their history, their vision and what they had studied so far, including a discussion of the Brookings Benchmarks document [

28]. When the council asked for feedback on the document, the CoP members noted that the earliest educational benchmark occurred when children were 11–12 years old; therefore, no data detailed the earliest years of life and educational quality in the document. The council then requested the group’s help in filling in these gaps. When the CoP members asked for the council’s feedback, they suggested developing a definition of well-being and creating a vision, mission and framework. The council also suggested that when the CoP had more structure, to establish a connection between the two entities with a member of each group attending the others’ meetings.

3.3. Developing an Official Name and Framework for the Advocates for Well-Being

These initial conversations with the mayor and BSC pointed to a clear need to formalize the CoP’s organizational structure and to clarify its intentions. Members first developed a strategic framework to aid in identifying who they were, defining well-being and determining action steps (see

Figure A1 in

Appendix).

Next, through internal and external audits, they determined an official name for the group, the Advocates for Well-Being (AWB). By selecting the word “Advocate”, the group embraced the goal of becoming a voice for others. They intend to speak for or on behalf of others, especially those whose voices are diminished [

29]. Inspired by the Reggio-Emilia community, they developed a clear vision for Brookings: a culture that holistically embraces and promotes the well-being of children and families. Their mission: to provide a platform for discussion and engagement by identifying and connecting stakeholders, building advocacy and support for well-being and creating a call to action.

Defining the concept of well-being proved more challenging, yet the AWB had previously embraced guiding principles from their first book study. “Well-being is described as a basic principle guiding the overall sense of community in Reggio Emilia; and one that emerged from a complex-cultural background of history, politics, and economic forces” ([

1], p. 37). “The notion of respecting children, more than just loving them, resonated with the group. Respect resembles love in its implicit aim of furtherance, but implies moral relations with others” ([

1], pp. 79–80). “In the community of Reggio Emilia, children are viewed as citizens having rights, including civil liability and equal opportunity to a full life. A life of well-being, free of obstacles to holistic development” ([

1], p. 84). D. Giovaninni [

19] stated the following regarding well-being and children, “Without a basis of well-being, there is no real possibility for growth, for development. This applies to children and families alike. We are talking about well-being in all senses…in relationships…in the environment…in physical requirements. It means for children that their needs are met. Of course, our reflections here about well-being are in the context of a community and are subjective. So, the care and well-being of one person connects to the well-being and care for another.” A key word from this vision, holistic, continually guided the AWB’s discussions. For example, the group determined that physical well-being includes the mind, body and spirit.

While the notion of well-being is certainly central to the Reggio-inspired practices, the concept still lacked clearly-defined, culturally-sensitive and measurable components for this context. To build their knowledge base, the AWB turned to the work of Gallup scientists who have been studying the demands of a life well-lived since the mid-20th century. In their research, Gallup conducted a comprehensive global study of 150 countries, providing a lens for over 98% of the world’s population. Five distinct factors emerged from this work: career, social, physical, financial and community [

30]. The AWB selected this work as a basis for their model and made one important modification: “Children have purpose and intent in their daily activities, but they do not have a “career”. In terms of purpose, the wider the range of possibilities for children, the more intense will be their motivations and the richer their experiences” ([

1], p. 54). Considering this, the AWB replaced the category of “career” with “inner/self” to describe purpose/intent as a factor of well-being.

The AWB also discussed the term education and its relationship to the five core components at length. They considered if perhaps a sixth component were necessary. Ultimately, the group determined that the concept of education resided within the community as a whole. They concluded that the delicate balance between these core components determines a holistic sense of well-being for a child, and a family. The AWB modified framework then included these descriptors: inner/self, social, physical, financial and community. The descriptors of the core components are intended to clarify and remain fluid as their work continues.

Lastly, determining action steps helped the AWB to also focus on future goals. For example, as the framework developed, they felt a recurring need to add specific detail to the concept of well-being. However, by focusing on the Reggio-inspired practice, the group refrained, believing that further refinement needed to emerge from the community’s collective understanding and to be promoted by the community. Still, creating the mission, vision and core components for a guide seemed essential since the community needed to have a better sense of the AWB perspectives as rooted in the book study. Taking this step of describing well-being in general terms was their first action step.

As the second and third action steps, the AWB next identified a need to research their own community to gain perspective and understanding; in a near parallel fashion, implementing the Delphi approach, as described below, contributed to this step. The group also values participatory research to build stakeholder interest in the work and to identify real community needs. Having the community itself periodically refine the concept of well-being and regularly determining areas of need according to a broad range of diverse perspectives, such as a wide variety of representatives from service agencies to family members, themselves, would help identify specific barriers to inclusiveness and access. These perspectives could guide the group in knowing where to advertise or how to ensure under-represented family voices are heard. These action steps would happen in a cyclical fashion through engagement and connection among a broad cross-section of community members. The AWB planned to collectively strategize about action steps or potential solutions, and they envisioned a community summit in the future. The final action step was perhaps the goal from the onset, to impact the community.

3.4. Delphi Approach

One of the challenges at the outset of this project was to broaden the knowledge base of the AWB members. To facilitate this, the AWB prioritized identifying the threats to well-being that were specific to their community. This important step in the advocacy process allowed the AWB to be more deliberate and current in their discussions and plans of action.

Given the scheduling difficulties of gathering community experts and the expense of running a focus group, they chose to implement the Delphi approach to learn about the needs that affect well-being for children and families in Brookings. The Delphi approach, developed by the RAND Corporation and gaining traction in the 1960s, elicits expert opinion on topics via distance. Traditionally, accomplished through mail, this step is now easily completed electronically through the Internet [

31]. The Delphi method has the advantage of eliciting expert opinion from a group without the potential for coercive influences that are sometimes observed in committee meetings or focus groups [

32].

The AWB implemented the Delphi approach by first identifying local experts in various fields, such as education, healthcare, business, social services, counseling and faith-based institutions. This long process required a considerable amount of brainstorming. Because the experts whose opinions are elicited are the ones who will determine the quality of information, the AWB strategically attempted to identify experts with areas of professional expertise correlated with the well-being framework described earlier in

Section 3.3. Finding one person who could address all five of the well-being core components was not the goal of the AWB. Instead, they aimed to compile a panel who could inform all five of the aspects of well-being with their combined knowledge.

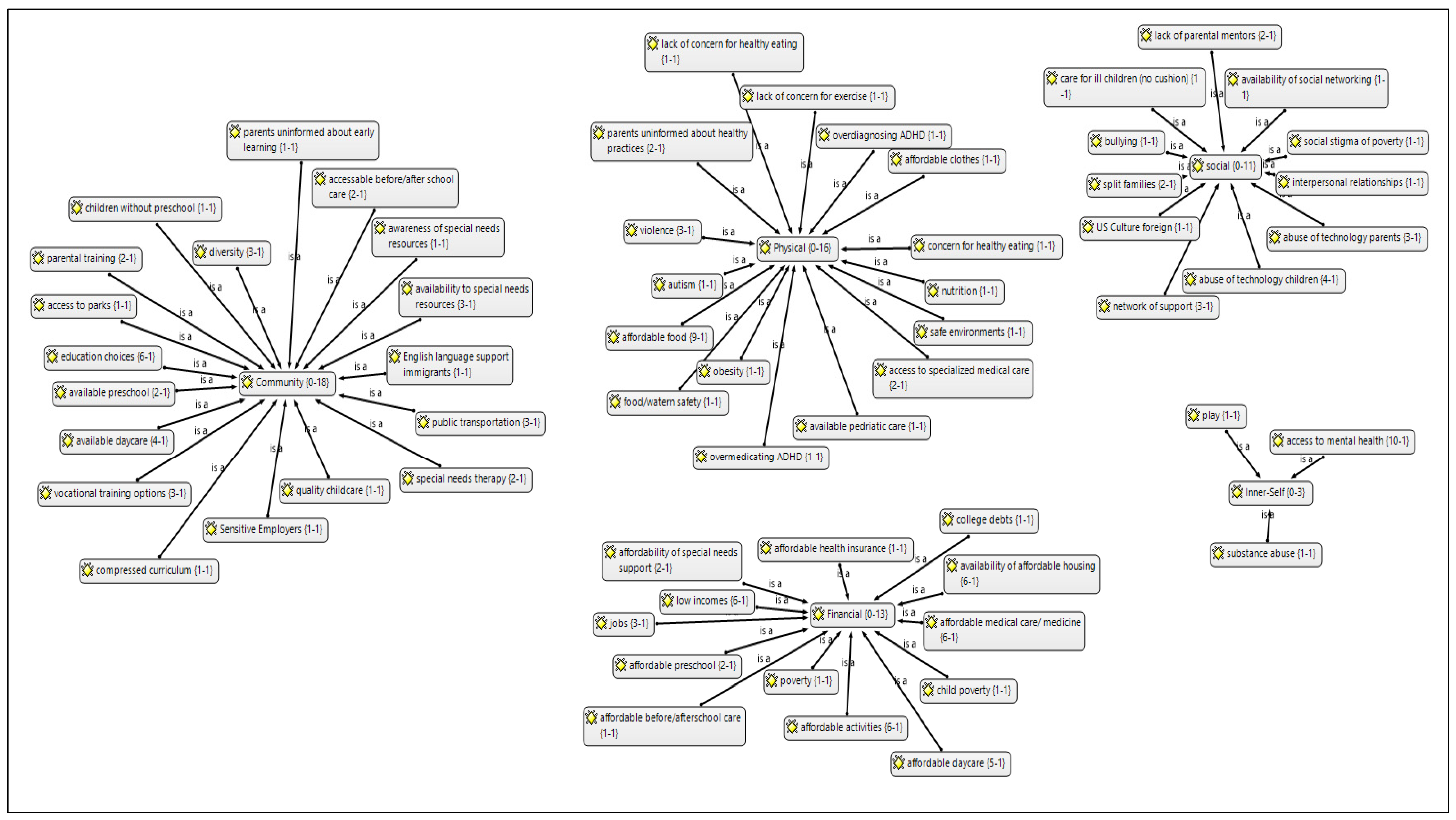

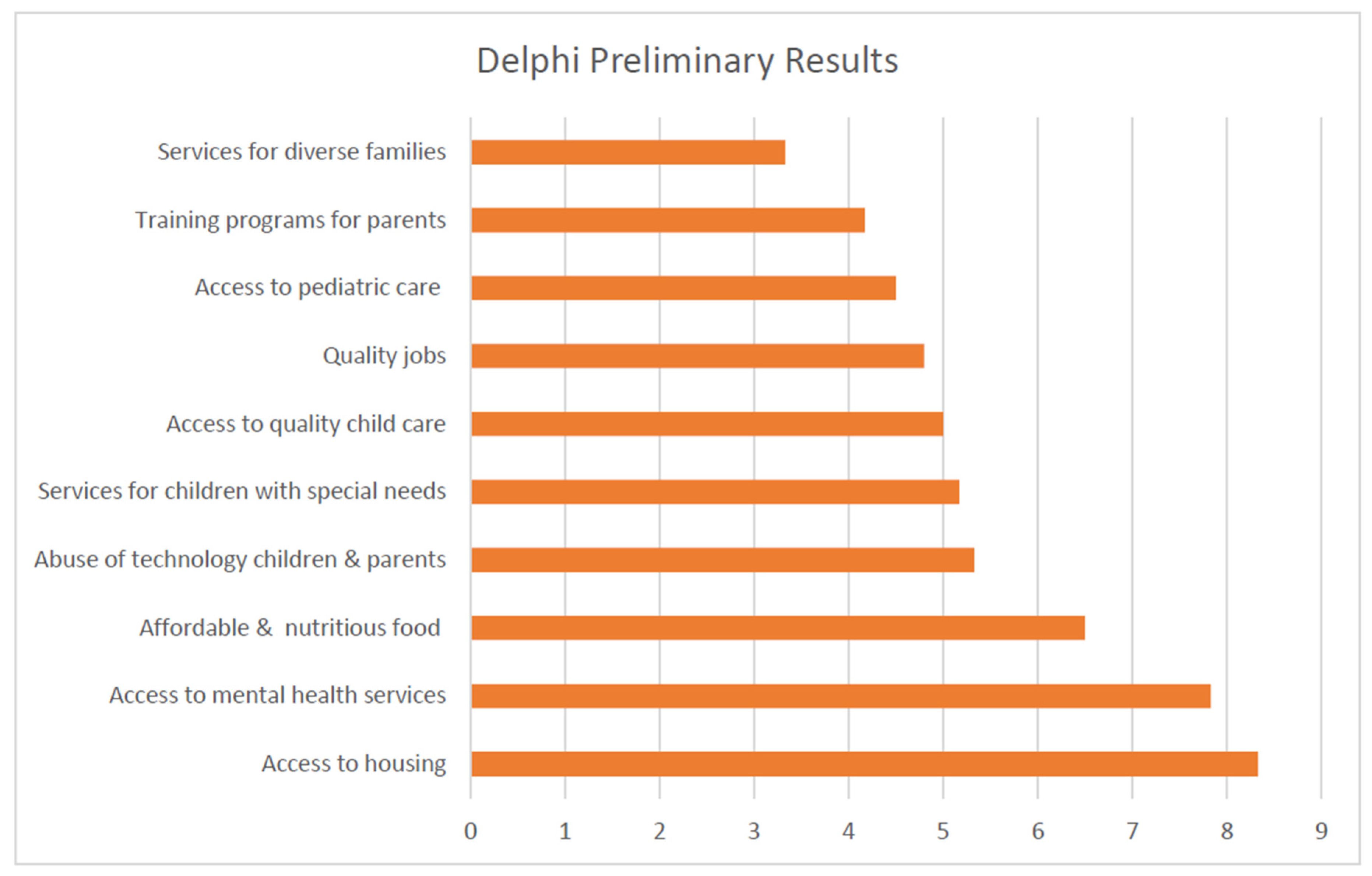

Once this group of experts was identified, the AWB began asking questions. The Delphi approach to needs-assessment traditionally asks three rounds of questions [

33]. For this study, the first round of questioning simply asked one question: list the top ten indicators of well-being for children and families in the Brookings area. The experts contributed a wide number of responses, identifying more than one hundred seventy initial indicators or potential threats to well-being. These individual indicators were coded using the ATLAS.ti 7 qualitative data analysis software. For the first round of coding, a line-by-line open coding process was utilized. These codes were then analyzed in the software’s network view in order to visually organize them in a meaningful manner. The framework of well-being, as the foundation to the AWB work, was utilized as the theory that deductively guided the organization of the codes into a network for further analysis (see

Figure A2 and

Figure A3). The

Figure A2 and

Figure A3 analysis showed the trends of three indicators of interest to well-being. The analysis revealed that the AWB intends to further investigate to obtain a clearer picture of the status quo. For example, the access to mental health code tended to be identified as a strong indicator of well-being.

Each AWB member participated in examining the results and contributed to the analysis of the key threats to well-being. After distilling the codes into the top ten indicators necessary for the second round, they contacted the experts again, asking them to rank the indicators in order of importance. Analysis of these data established a consensus of expert opinion, thus eliminating the need for a third round.

Using this Delphi approach to needs assessment, the community experts in Brookings have identified important aspects of well-being for children and families; the top three include access to housing, access to mental health services and access to affordable food. The third indicator from

Figure A2 and

Figure A3, affordable and nutritious food, surprised the AWB because Brookings is a rural community with rich and productive farmland and is home to a land-grant university with expertise in agricultural research. The apparent lack of access to nutritious food and its high rank as an indicator of concern demonstrates the importance of eliciting information from community experts when conducting a needs analysis. Moreover, this finding illustrates how needs that are fundamental to the well-being of children and family in any area can be invisible to others. However, to verify this understanding of need, the AWB intends to seek out family members’ perspectives on well-being, specifically on these three indicators.

3.5. Developing a Call to Action

The AWB’s goal to foster community cultural values that embrace and promote the well-being of children and families led to creating a plan for a stakeholder platform discussion. The AWB members asked possible “what if” questions, such as “What if Brookings had one place for families to access all family resources that supported well-being? What if all families had a place where their needs were heard? What if all resources for families worked together to improve well-being, collaborated and supported each other or looked at well-being in a holistic way? Additionally, what if all families in Brookings had a strong and healthy well-being?” in order to develop a framework for the stakeholder platform.

Typically, community agencies attempt to solve education, health and socioeconomic problems for their stakeholders by identifying isolated problems under their jurisdiction based on needs or deficit-based analyses. Once these deficits are determined, separate agencies assume responsibilities for improving conditions in specific areas. Often, the planning process omits the voices of those directly affected by the problem. This isolated approach assumes that the agencies can recognize by themselves what well-being, situated in this context, comprises. Second, the traditional approach assumes that community well-being can be improved by fragmenting and treating the components as independent variables. This simplistic view fails to address the complex interactive nature of communities, wherein education, economics, health and local culture create unique situations. The AWB aims for a holistic approach to community well-being with an inclusive consensus-building model wherein multiple stakeholders, including those directly impacted, collaboratively define a dynamic rather than a static vision of well-being and work together to achieve it.

Initially, the AWB considered three phases of action: raising awareness, educating the community and taking action. They raised awareness by meeting with others during the city’s Open Mic Night, a forum to connect with the creative class; and Engage Brookings, a local website with an online tool for gathering community input on city policy. To educate the community and take action, the AWB considered developing a one-day symposium or well-being conference, with follow-up focus groups. For advertising these events, the group recognized that typical media messages may not reach or engage those most directly affected by issues of well-being. The solution required additional, creative ideas for outreach, such as multi-lingual translations for promotional and educational materials, visits over the lunch hour to local manufacturers and transportation services to events.

3.6. Seeking Funding through the Bush Foundation

Creating a call to action requires funding. The AWB applied to the Bush Foundation to seek support for community-wide dialogues on the topic of well-being. Although their application was not funded, the exercise of writing the proposal helped them to clarify their vision and to develop a strategic plan. It included these steps: identify and connect stakeholders, build advocacy and support for well-being and collectively strategize about action steps or potential solutions. Using the Reggio Emilia philosophy, the AWB planned to use “provocations” to attract interest and spark curiosity in community well-being with a focus on their youngest citizens. The AWB continues to seek funding for the call to action.

4. Implications and Future Directions: In Pursuit of Sustainability

The AWB book study generated a shared vision of valuing children as central to community well-being. This main idea serves as the common concern for the CoP that the AWB developed. In reviewing their journey to date, four pieces of work that are common to CoPs and that continue to describe their process emerged. First, their members created relationships through the process of inquiry during the book study; second, they learned from each other and through each other’s experiences; third, the AWB coalesced around a common goal that required them to investigate and consider their own community culture; finally, they gained a new understanding of the task before them [

2]. However, describing these activities in a linear fashion ignores the cyclical nature of CoP work. For example, the contacts and relationships within and across the community have grown organically as members engage with others. Through collaboration, they enlarged their understanding of community needs that informs new possibilities for actions. Through this increased connectivity, they pursue the goal of a “critical mass needed to evolve into a sustainable entity” ([

2], p. 2). Thus, developing a CoP becomes essential for permanent cultural change. Sustainability in this context means a community that embraces the well-being of children and families as its core institutional value and seeks continual renewal of that vision.

4.1. Continued Data Collection

The Delphi method is limited because it only provides an outsider’s etic perspective of the needs of the target population. While the experts, in many cases, work closely with the at-risk and in-need population of the city, they are not living in those conditions themselves. This naturally imposes a limit to the scope of information, as well as a contextualized understanding of the possible threats to the well-being of children and families. To address this information deficit, the AWB are considering a participatory method of information gathering that produces a more inclusive dataset.

In addition, utilizing participatory methodology, such as Photo Voice, has the capacity to empower the at-risk population [

34]. From a Freirean context, this benefit addresses the weakness of the Delphi in that a participatory approach does not treat the target population as objects of research. Instead, marginalized people are recognized as the experts on their own well-being with voices that have equal weight in the needs-assessment process [

35]. This type of community empowerment and coming to voice is highly consistent with the goals and vision of the AWB. Using an approach to knowledge gathering from adults also aligns ideologically with a community-initiated approach to knowledge building that is central to the Reggio Emilia teaching philosophy. All of these ideals provided the impetus for the Brookings AWB. In their recent meeting, they reviewed survey data from local agency employees who work with children and families. Since families have not yet been asked directly about child and family well-being, this will be their next step in data collection in order to gather many perspectives and further refine the data.

4.2. Deeper Connections with Community

The AWB has sought to create deeper connections with area agencies, such as Brookings Area United Way. Last fall, the AWB met with the Executive Director to explore ways to connect with existing initiatives. Connecting to those and creating an integrated call to action are the strategic goal. The AWB also met with the Brookings Economic Development Corporation Entrepreneurship Program Coordinator to discuss possible connections to their BEDC Visioning Charettes and strategic planning document. The AWB identified two ways to assist with the BEDC’s strategic goals: (1) to engage the university personnel in meaningful partnerships; and (2) to create an engaging social ecosystem in the communities with access for all residents. Through dialogue, the AWB decided to focus primarily on influencing this last goal. The AWB also have been invited to circle back around and meet a second time with the Brookings Sustainability Council after a second Open Mic conversation.

Recognizing Undergraduates as an Asset: Several members of the original book study group have university faculty appointments in teacher education. As such, they occasionally mentor students majoring in education or a related area, who seek opportunities to dig deeper, to serve children in extended ways or to research issues related to teaching. Some of these university students also look for opportunities to “honor” a course to fulfill requirements for the Honors College; they look for undergraduate research opportunities, and the university encourages this activity as a way to enrich student experiences; advocacy is one of those experiences.

Including undergraduates as AWB members also benefits the group because students add energy and creative perspectives. In addition, students bring possible collaborative opportunities that extend the group’s reach and provide resources. For example, currently, a university student who is also a member of the Student Program of the National Education Association, an organization that offers grants to promote collaboration and outreach between university students and the community, wrote a proposal to fund the AWB’s work. This proposal supported an educational goal for the community because the AWB can now establish a small library of materials and books related to well-being. Undergraduate research and data collection possibilities also exist within this work, as either research assistants or full partnership collaborations.

4.3. Selection of a New Text

To keep the AWB members engaged in their own learning, they have selected

A More Beautiful Question: The Power of Inquiry to Spark Breakthrough Ideas, by Warren Berger [

36], for their next collaborative book study. Continuing with a book discussion allows them to reach out to community members, build the CoP and widen the circle of AWB. Since their first book study, six key community members have joined the core group as active members. This process epitomizes the cyclic nature of inquiry and CoP development.

4.4. Alternative Approaches to the Call to Action

Pursuing the AWB’s goals requires finding new funding sources, seeking support from foundations and finding or creating a home within the existing institutional and community structures in a way that is transparent, supportive and effective. These are the challenges that the AWB faces.

The opportunity to capture their work by writing this current manuscript in the group’s development adds perspective in a similar way that writing and reviewing the work accomplished in the grant writing process. The AWB find themselves immersed in the CoP life cycle as they move through the different phases of growth, knowledge generation and revitalization [

3].