1. Introduction

Artificial Intelligence (AI)—understood as a set of techniques and systems designed to simulate human reasoning and learning processes—has emerged as a strategic tool in the fight against disinformation. Its potential to automate verification tasks, detect deceptive patterns, and process large amounts of data has generated growing interest in academic and professional fields (

Gutiérrez-Caneda and Vázquez-Herrero 2024). However, the incorporation of these technologies also raises ethical, social, and financial questions that must be critically examined to understand their scope and limitations.

The aim of this study is to analyze the application of AI in the fight against disinformation through an examination of several European initiatives compiled by the SmartVote project, which is being developed by a consortium of six partners from Spain and Portugal, representing media, civil society, and academia, coordinated by Fundación Cibervoluntarios. They specifically aim to tackle the issue of disinformation and its impact during electoral processes and referendums as a threat to democracy and the role of news, journalism, and technology in the process (

Paisana et al. 2025).

This research explores the key features, similarities, differences, contributions, and limitations of these projects. The relevance of the study focuses on two main areas. First, the research offers a systematic mapping of the technologies and objectives guiding these types of projects in counter-disinformation. Secondly, the study may provide comparative criteria of practical value for different audiences, as it allows us to identify trends and gaps in European investment and to establish patterns that may help plan funding programs and design regulatory frameworks.

The methodological design integrates an exploratory and descriptive approach based on the triangulation of quantitative and qualitative techniques. A systematic documentary analysis of institutional and technical sources—official websites, reports, public repositories, and project fact sheets—was conducted to identify the types of artificial intelligence employed, the areas of impact, the stakeholders involved, and the funding. In parallel, a structured questionnaire was administered to the coordinators and technical leaders of the initiatives, aimed at understanding their perceptions of the results achieved and the main future challenges in the use of AI against disinformation. Information from both sources was subjected to a homogeneous coding process, which made it possible to compare project features and establish common patterns of development, cooperation, and technological evolution in the European context.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Disinformation: Definitions and Conceptualization

The concept of disinformation has evolved from the first restrictive approaches centered on the term “fake news” to broader and more complex analytical frameworks due both to the explicative insufficiency of the initial concept and to its progressive politicization in the public debate, which has made many authors avoid the term for considering it reductionist and normatively charged (

Guallar et al. 2020;

Magallón-Rosa 2022).

In this context, the contribution of

Wardle and Derakhshan (

2017,

2018) is foundational, as they propose the information disorder framework, which conceives disinformation not as an isolated product but as a communicative process. This approach distinguishes between misinformation (false information shared without the intention to cause harm), disinformation (false or manipulated content deliberately disseminated to cause harm), and malinformation (genuine content used for harmful purposes, such as leaks, hate speech, or digital harassment). This taxonomy shifts the analytical focus from factual accuracy to intentionality, context, and the social impact of messages.

In line with this perspective, the

European Commission (

2018) formalized a regulatory definition of disinformation as “false, inaccurate, or misleading information designed, presented, and disseminated to cause public harm or for profit.”

Diverse studies conceptualize disinformation as a structural phenomenon that extends well beyond fake news to encompass rumors, propaganda, media manipulation, and biased content aimed at shaping perceptions and behaviors (

Bennett and Livingston 2018;

Bergmann 2020;

Waisbord 2020). Within this framework, disinformation is understood as a systemic threat to democracy, as it contaminates public deliberative spaces and provides distorted representations of reality, particularly in highly polarized contexts.

Regarding the social effects of disinformation, the literature consistently indicates that it produces multidimensional consequences affecting political, cultural, psychological, and communicative spheres. From a democratic standpoint, numerous studies document its capacity to erode trust in institutions, undermine the legitimacy of political actors, and distort electoral processes (

Bennett and Livingston 2018;

Bergmann 2020;

Rodríguez Pérez et al. 2021).

From a psychosocial perspective, disinformation operates primarily through emotional manipulation. Previous research has shown that disinformative content disproportionately appeals to negative emotions—especially fear and anger—which are highly effective in driving mobilization and affective polarization (

Weeks 2015;

Nai 2018;

Chadwick and Vaccari 2019). Fear tends to generate destabilization and a sense of chaos, while anger reinforces dynamics of identity-based confrontation.

These emotional mechanisms are further amplified by phenomena such as confirmation bias and the backfire effect, which strengthen pre-existing beliefs even in the presence of corrective evidence. The algorithmic architecture of digital platforms contributes to this process by fostering echo chambers and identity bubbles, thereby limiting exposure to divergent perspectives (

Orbegozo-Terradillos et al. 2020).

2.2. Disinformation, AI, and Journalism

Disinformation is one of the main challenges of the contemporary media ecosystem and a direct threat to the democratic functioning of societies. The ability to produce and disseminate misleading content on a large scale has increased exponentially due to digitalization, technological convergence, and the emergence of global communication platforms (

Bontridder and Poullet 2021). Artificial intelligence is expected to further emphasize these dynamics but also to help identify specific patterns and develop early-warning mechanisms.

The first approaches to AI, in the mid-20th century, were based on the symbolic or logical paradigm, which sought to program systems capable of reproducing human reasoning processes through explicit rules. Although their applications were limited, they laid the foundations for subsequent developments in natural language processing and expert systems. In journalism, these technologies had a marginal impact, restricted to the digitization of databases and the automation of administrative tasks (

Tejedor and Vila 2021).

In this context, journalism faces a paradox: on the one hand, the need to preserve its social function as a guarantor of truthfulness and transparency, and on the other, the obligation to adapt to an information environment heavily mediated by algorithms and artificial intelligence (AI) systems.

With the rise in machine learning in recent decades, AI experienced a qualitative leap. Access to large volumes of data (big data) and increased computational capacity made it possible for algorithms to learn from patterns and make more accurate predictions.

In journalism, this stage coincided with the expansion of the internet and the emergence of the first algorithmic verification tools.

García-Marín et al. (

2022) highlight that the intersection of computational linguistics, algorithms, and big data opened new paths for counter-disinformation by enabling the identification of false narratives within large textual corpora.

Today, generative AI—based on deep neural networks and large language models (LLMs)—has marked a turning point. These systems are capable of producing text, images, audio, and video with a level of realism that is increasingly difficult to distinguish from human-generated material.

This has created a dual effect: on one hand, tools such as ChatGPT or deepfake-detection systems are used to strengthen verification efforts; on the other, the same technology fuels new forms of disinformation that are difficult to trace and verify (

Peña-Fernández et al. 2023).

In sum, the evolution of AI and its relationship with communication has progressed from the mere automation of tasks to the creation of content indistinguishable from that produced by humans. This process presents an ambivalent scenario in which the same systems that threaten to multiply disinformation also offer tools to fight it.

Applications of AI in Journalism

Content automation, pattern processing and detection in large databases, recommendation systems, and their application to fact-checking are some of the main uses of AI in contemporary journalism.

So-called robot journalism, or automated journalism, uses algorithms to generate informational texts based on structured databases. These practices, increasingly common in news agencies and newsrooms, make it possible to produce stories on sports, finance, or election results quickly and at low cost. However, although these pieces meet basic accuracy criteria, they lack the interpretative and narrative richness of human journalism (

Verma 2024).

Recommendation systems based on AI allow us to tailor the information offering to the preferences of each user, increasing the relevance of the content consumed. However, this practice raises risks of information bubbles and echo chambers that may reinforce social polarization by limiting exposure to diverse perspectives (

Bontridder and Poullet 2021).

As noted by

Gutiérrez-Caneda and Vázquez-Herrero (

2024), AI has been incorporated into different stages of fact-checking: from detecting rumors and questionable content on social media to automatically comparing public statements against verified databases. These tools help accelerate the work of journalists and optimize coverage of viral phenomena.

Beyond text, AI is also applied to the identification of manipulated images, falsified audio, and videos created through deepfake techniques. This expanding field is crucial, given that contemporary disinformation unfolds across multiple formats and platforms.

AI systems support newsrooms in managing vast amounts of data from open sources, official documents, or social networks. This processing not only enables fact-checking but also allows for the anticipation of trends and the detection of coordinated disinformation campaigns (

Santos 2023).

2.3. The Role of AI in the Disinformation Ecosystems: Uses, Effects, and Contextual Constraints

There is broad consensus in the literature that artificial intelligence plays a dual role in relation to disinformation, capable of both reinforcing and undermining informational integrity (

Niño Romero 2025;

Peña-Fernández et al. 2023). This ambivalent character is particularly evident with the expansion of generative AI, whose language models, image-generation systems, and audiovisual synthesis technologies have profoundly altered the processes of production, circulation, and verification of informational content.

Several studies emphasize that AI does not introduce an isolated qualitative change but rather intensifies dynamics already present in digital ecosystems, such as automation, algorithmic personalization, and virality (

Barredo Ibáñez et al. 2023;

Niño Romero 2025). From this perspective, AI acts as a capacity amplifier: it increases the efficiency of verification and deception detection while also multiplying the scale, speed, and sophistication of disinformation.

One of the strongest points of consensus in the literature is the potential of AI to improve the efficiency and accuracy of verification processes. European public broadcasters have incorporated automated verification systems based on machine learning, which allow for the real-time analysis of large volumes of information, the detection of anomalous patterns, and the reduction in errors in informational content (

Fieiras Ceide et al. 2022).

AI is also beginning to emerge as a support tool for journalistic work. Approximately 41.6% of communication professionals consider algorithms to be effective instruments for information verification, particularly in tasks that exceed human capacity in terms of volume or speed (

Peña-Fernández et al. 2023). In this regard, automation can help reduce the burden of routine tasks and allow journalists to focus on contextualization, investigation, and critical analysis.

Similarly, fact-checking platforms have adopted algorithmic tools for content auditing and early detection of disinformation, pointing to a gradual transformation of professional practices and a hybridization of human competencies and automated systems (

Sánchez González et al. 2022).

In addition, the introduction of informational labels and explanatory mechanisms within journalistic algorithms has been identified as a best practice to strengthen trust and accountability in information.

Against this backdrop, the primary risk identified across studies is AI’s ability to generate highly plausible false content. The literature highlights that the creation of deepfakes through generative technologies constitutes a significant threat to the reputation of individuals and institutions, as well as to the credibility of audiovisual evidence (

Ballesteros-Aguayo and Ruiz del Olmo 2024).

Consequently, the proliferation of AI-generated or AI-amplified disinformation erodes public trust in the media, digital platforms, and democratic institutions. At the same time, perceptions of algorithmic bias are associated with increased skepticism toward information sources, undermining the legitimacy of journalism and the informational system as a whole (

Pastora Estebanez and García-Faroldi 2025;

Niño Romero 2025).

2.4. AI and Fact-Checking: Methodology, Progress and Limitations

Natural Language Processing (NLP) algorithms enable the analysis of large amounts of text in order to detect patterns, inconsistencies, or claims that may require verification. These techniques are applied, for example, to the identification of political discourse, viral rumors, or news with high social impact (

Santos 2023).

The literature published so far consistently highlights the need for AI systems to operate under human supervision. The human-in-the-loop approach combines the speed and analytical capacity of algorithms with human judgment. According to

Santos (

2023), this complementarity reduces errors and prevents the algorithm from reproducing biases or generating false positives.

Along the same lines,

Gutiérrez-Caneda and Vázquez-Herrero (

2024) emphasize that AI supports fact-checking by automating repetitive tasks, shortening response times, and improving accuracy in the identification of false information. These advantages become particularly relevant during information crises or electoral campaigns, contexts in which it is essential to quickly correct disinformation in order to mitigate its impact.

Despite these advances, the application of AI to fact-checking faces multiple challenges:

Technological gaps: disparities in resources across countries or media organizations limit the implementation of advanced tools, increasing inequalities in the fight against disinformation;

Overreliance on technology: there is a risk that journalists and audiences may delegate too much critical judgment to automated systems, weakening editorial oversight and human evaluation.

2.5. Social and Professional Aspects of AI in Journalism

The use of AI frees professionals from routine tasks—such as transcription, data classification, or writing simple notes—allowing them to focus on higher value-added activities like investigation and critical analysis (

Verma 2024). However, this transformation also raises concerns about job loss and precarization.

Studies show that audiences do not perceive major differences in the quality and credibility of texts generated by AI versus those written by human journalists, especially when reporting on official statistics, in addition to economic, sports, and other results.

Nonetheless, human-produced content tends to be considered more engaging and easier to read, as it conveys empathy and cultural context (

Peña-Fernández et al. 2023). This difference suggests that the added value of human journalism lies in its ability to emotionally connect with the audience. Thus, story-driven journalism, interviews, and investigative reporting continue to offer a distinctive added value.

In this context, the incorporation of AI requires journalists to assume roles related to oversight, data management, and ethical evaluation.

Abbood (

2024) warns that excessive automation may erode critical competencies, relegating professionals to a secondary role as algorithm validators. For this reason, continuous training that combines technical skills with ethical sensitivity is essential.

AI systems inherit the biases present in their training data, which may lead to discriminatory outcomes or algorithmic biases.

Reyes Hidalgo and Burgos Zambrano (

2025) argue that, without proper oversight mechanisms, algorithms may reproduce stereotypes and perpetuate social inequalities.

Santos (

2023), meanwhile, emphasizes that any implementation of AI in journalism must ensure user privacy, explain the criteria of algorithmic decisions, and establish accountability mechanisms for potential errors. A lack of transparency may undermine trust in the media and in the technology itself.

Another risk identified is the excessive dependence on major technology platforms that develop and control AI tools. This concentration of power limits media autonomy and may influence editorial practices (

Bontridder and Poullet 2021).

Beyond the technological perspective,

Bontridder and Poullet (

2021) stress that the problem of disinformation is linked to the internet’s financial model, which is based on advertising and the attention economy. As long as revenues depend so heavily on clicks and virality, there will remain a structural incentive to circulate fake or sensationalist content, limiting the effectiveness of any purely technological solution.

2.6. Hybrid Models of Human–Machine Collaboration

Tejedor and Vila (

2021) introduce the notion of exo journalism, a model that combines the capacities of AI in content automation and fact-checking with human creativity and critical judgment. This model recognizes that AI can enhance professional practice in areas such as news detection, personalization, or automatic text generation, but emphasizes that its value lies in reinforcing—rather than replacing—the work of journalists.

Verma (

2024) argues for the need for a symbiotic relationship between AI and professionals, in which machines take on mechanical and repetitive tasks, while humans focus on interpretation, contextual analysis, and ethical responsibility. This complementarity not only improves the quality of information but also preserves the essence of journalism as a social activity.

For this hybrid model to be viable, it is essential that journalists develop new technical competencies related to algorithm management, data analysis, and digital ethics.

Abbood (

2024) highlights that the integration of AI requires training strategies that ensure audience trust and the maintenance of information quality standards.

3. Methodology

3.1. Justification and Relevance of the Study

The study provides a mapping of the technologies and purposes of European projects that incorporate AI in the fight against disinformation within a landscape characterized by dispersed initiatives, the absence of shared taxonomies, and the rapid obsolescence of some experiences (

Moreno Espinosa et al. 2024).

Issues such as European digital sovereignty, technological development grounded in democratic principles, and the accountability of the projects themselves are established as key axes for their evaluation.

Beyond its descriptive value, the study makes a practical contribution to ongoing social debates on the governance of artificial intelligence and the resilience of democratic information systems. This knowledge is socially relevant insofar as disinformation directly affects electoral processes, public trust, and democratic deliberation. Consequently, any AI-based solution—such as those analyzed here—becomes a matter of public interest.

Furthermore, the research generates comparative criteria with practical value for diverse audiences. In this regard, it aligns with previous efforts such as those of

Moreno Espinosa et al. (

2024) and

Montoro-Montarroso et al. (

2023), while also enabling the identification of trends and gaps in European investment. This latter contribution is highly relevant for public policymakers, as it supports the planning of funding programs and the design of regulatory frameworks. For media professionals, the study provides a cross-cutting perspective on the tools currently being developed and how they might be integrated into journalistic routines. Finally, for academic research teams, the work offers a systematized foundation that facilitates future comparisons, longitudinal evaluations, and the development of theoretical frameworks that help explain the interaction between artificial intelligence and disinformation dynamics.

3.2. Methodological Design

The research employs an exploratory and descriptive methodological design with the objective of examining the role of AI in European initiatives aimed at fighting disinformation. The exploratory nature responds to the fact that this field of study is recent, dynamic, and still insufficiently systematized. Likewise, the descriptive orientation is justified by the need to catalog, organize, and compare these projects.

The mixed nature of the study stems from the integration of quantitative techniques (variable coding and correlations) with qualitative evidence (open-ended questionnaires for project coordinators). Methodological triangulation guidelines are followed to provide greater depth and soundness to the analysis.

The primary source of the study is the database developed by the SmartVote project, which compiled a set of international initiatives related to disinformation detection and the use of artificial intelligence. The overall objective of the SmartVote project is to ensure that all people have access to, learn about, and use technology to promote their autonomy, increasing their opportunities, strengthening their rights, and encouraging their social participation (

Paisana et al. 2025). SmartVote was designed to encourage responsible and ethical uses of technology while safeguarding citizens’ rights. The initiative addresses disinformation as a way to foster a more informed, engaged, and participatory democratic process. The goal is to develop critical thinking, especially among the youth, combining the development of digital literacy materials with the improvement of an artificial intelligence-based tool to identify disinformation.

This directory constitutes the central corpus of analysis and includes a total of 125 projects, of which 52 present an explicit use of AI. The database under analysis is limited to projects developed in Western contexts—mainly in the United States and Europe—with information available in English, Spanish, or Portuguese. Consequently, it is not intended as an exhaustive mapping but rather as an exploratory exercise, constrained by the limitations arising from the availability of public information and access to key data, such as funding sources or the actual implementation of artificial intelligence systems (

Paisana et al. 2025). This research focuses specifically on the 25 projects that make up the European subsample.

1The sample is selective, intentional, and theoretically informed: projects are included based on (a) being based or coordinated in Europe, (b) bearing an explicit reference to the use of AI, and (c) showing a minimum level of documental traceability (at least one verifiable institutional or technical source). Projects lacking sufficient information for basic coding are excluded, as this study prioritizes comparability and documental quality over exhaustiveness. This approach allows us to build a more consistent analytical framework. It also guarantees that the comparative analysis is grounded in empirically observable features rather than in assumptions about technological use or relevance of the projects.

3.3. Research Objectives and Questions

General objective: To analyze European initiatives that integrate AI in the fight against disinformation, paying attention to their characteristics, similarities, differences, and contributions.

Specific objectives:

To catalog and systematize European projects that incorporate AI for counter-disinformation;

To compare the AI technologies employed and the objectives pursued, highlighting innovative contributions;

To explore trends in the evolution of AI applied to disinformation.

Main research question: How do European projects employ AI to face disinformation, and what are their contributions and prospects for evolution?

Specific research questions: What types of AI are used? What strategic objectives predominate, and what areas of impact are identified? What patterns of collaboration and funding emerge? What trends in evolution can be observed?

3.4. Methods

The study relies on a combination of two complementary methods. First, a systematic documentary analysis is conducted based on the publicly available self-descriptions found on the websites, call documents, reports, and technical summaries of the initiatives.

This approach makes it possible to extract comparable information from self-referential narratives, subjecting them to a homogeneous coding process. The coding was conducted on the basis of a set of previously defined variables, encompassing both technological categories (type of AI, level of automation, and multimodal character) and organizational and strategic variables (project objectives, involved stakeholders, scope of application, and scale of funding).

Characteristics and design. This includes the type of AI employed by each project. NLP is used to analyze texts, identify false statements, and track misleading narratives in different languages. Computer vision enables the detection of visual falsifications, or deepfakes, through the automated analysis of images and videos. Classical machine learning is applied to data classification and the detection of recurring patterns, while deep learning, or neural networks, enables more complex models capable of recognizing semantic or visual relationships with greater precision. The analysis also considers the areas of impact of each project or initiative: media content verification, media literacy, and efforts related to governance, ethics, and public policy.

Types of stakeholders, geographic distribution by country, and budget. This includes documenting the number of participating partners and the types of stakeholders involved (universities and research centers, media organizations, technology companies, civil society organizations, and public institutions), as well as the countries where the initiatives are developed.

To organize the information, a coding guide was created (

Wimmer and Dominick 2013). The procedure was applied in two phases: first, a pilot test with a small set of projects, and then the full coding phase. This ensured consistency in the interpretation of results. Discrepancies identified during the initial coding were jointly reviewed and used to refine variable definitions prior to the full coding phase.

2To address cases of analytical overlap, a dominant coding logic was applied. Each variable was assigned following explicit decision rules included in the coding guide, which specified criteria for inclusion, exclusion, and hierarchical prioritization in situations where a project pursued multiple objectives. In such cases, the dominant category was coded according to the primary function declared in the official documentation and the central role of the tool within the project.

A structured questionnaire was also administered (

Creswell 2014) and distributed via email to coordinators and technical leads of the selected projects. The questionnaire was completed by four interviewees, and the instrument included questions aimed at exploring the objectives of each initiative and the main future challenges for the use of AI against disinformation in Europe.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Characteristics and Design of AI Tools Used in Fact-Checking

4.1.1. Type of AI Technology

The development of AI applied to the fight against disinformation is clearly shaped by the exponential growth of the problem. The tools analyzed have been used in two ways: in a “downstream” logic, identifying disinformation content and combating it, often with the help of fact-checking platforms, and in an “upstream” logic, proactively preventing the spread of disinformation content by signaling or even removing it before it is disseminated (

Paisana et al. 2025).

Until now, there has been a proliferation of publicly funded projects (particularly by the European Union) and privately funded ones, in which large companies linked to online networks have promoted the development of their own AI to fight against false content on social platforms (

Pilati and Venturini 2024).

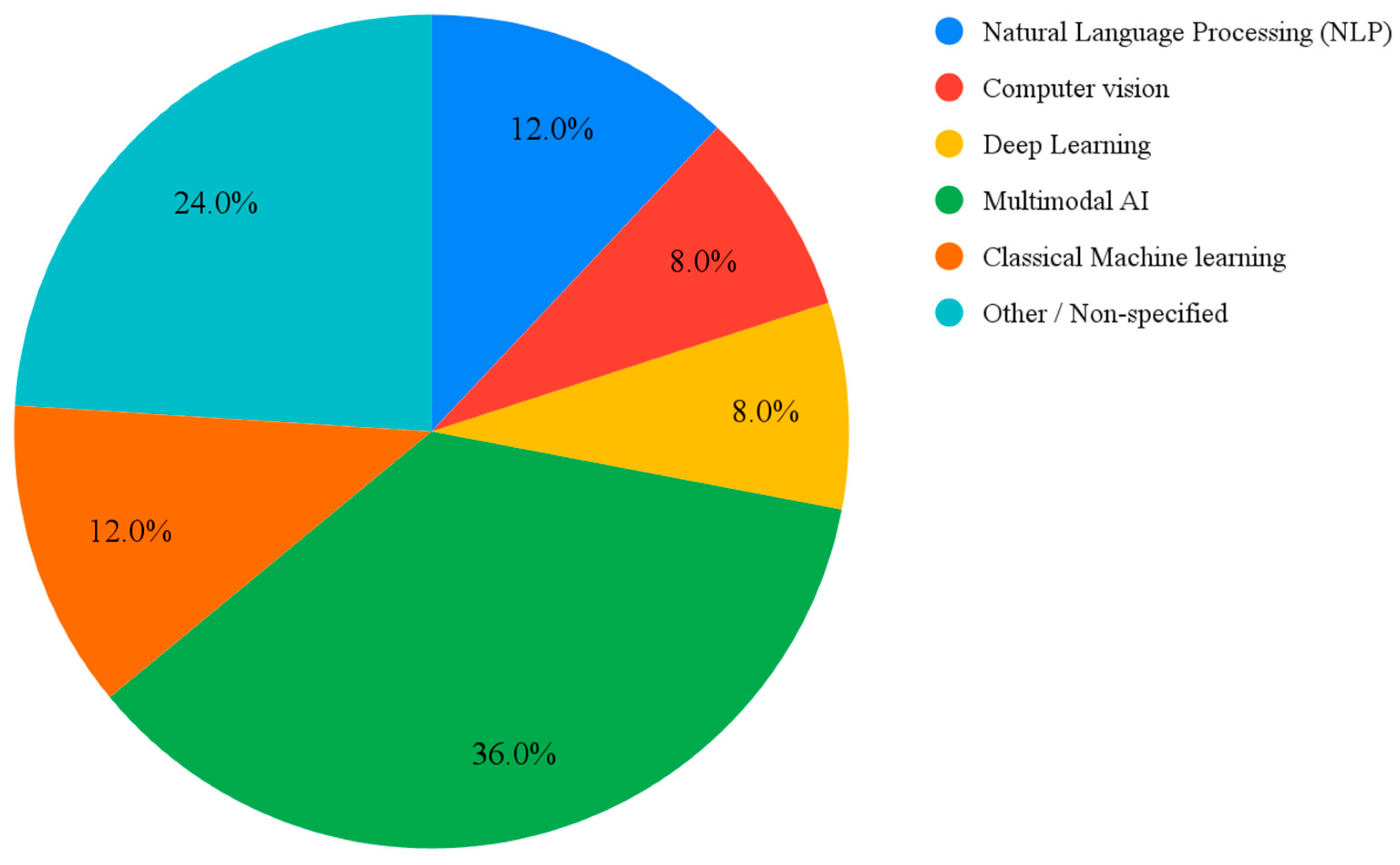

The analysis of the 25 European projects reveals a multimodal orientation in the use of artificial intelligence applied to counter-disinformation. The combination of multiple types of AI—especially NLP and machine and/or deep learning—is present in 9 of the projects analyzed (36%) and constitutes the backbone of automated detection, classification, and verification strategies (

Figure 1).

In many cases, the prominence of NLP-based tools reinforces the understanding of disinformation as a narrative and discursive phenomenon (

Wardle and Derakhshan 2018), in which meaning is constructed through repetition, framing, and semantic association rather than through isolated false statements.

These solutions range from text-mining systems and sentiment analysis to semantic engines capable of tracking disinformation narratives across languages. Their logic is based on the ability of algorithms to recognize recurrent discursive patterns—structures of false claims, linguistic biases, or associations among conspiratorial terms—and match them to verified sources.

In these projects, language is studied as an interdependent network of meanings in order to trace the semantic connections that support or legitimize potentially false or misleading narratives so that journalists or citizens can later complete the analysis through verification tasks. This approach confirms the trend described by

Gutiérrez-Caneda and Vázquez-Herrero (

2024), who argue that AI has transformed fact-checking into a hybrid process that combines computational analysis with editorial interpretation.

The exponential increase in the use of tools such as ChatGPT may make these synergies increasingly necessary, given that the primary function of this type of generative intelligence is not the factual accuracy of its responses but rather speed, content personalization, and the strengthening of its dominant position within the attention economy.

Computer vision—present in only two projects (8%), at least as the sole type of AI employed—is emerging as an expanding field within European counter-disinformation strategies, particularly aimed at detecting manipulated visual content. In these initiatives, AI is applied to the automated analysis of images and videos to identify anomalies in textures, lighting, or movement indicative of potential falsifications. However, the limited presence of computer vision contrasts with the growing relevance of audiovisual disinformation (

Sharma et al. 2020), suggesting a mismatch between the multimodal evolution of false content and the technological capacity of verification initiatives.

Deep learning technologies (8%) and classical machine learning techniques (12%) appear explicitly in a limited number of cases as standalone solutions—two and three projects, respectively. However, it is likely that their presence is greater than the data suggest, as they often constitute the algorithmic foundation of other systems. These techniques are typically used in internal tasks of classification, prediction, or detection that support the operation of the user-facing tools.

4.1.2. Areas of Application

Although thematic diversity is broad, most AI initiatives aimed at combating disinformation in Europe seek to strengthen journalistic verification processes and improve information traceability online (

Table 1).

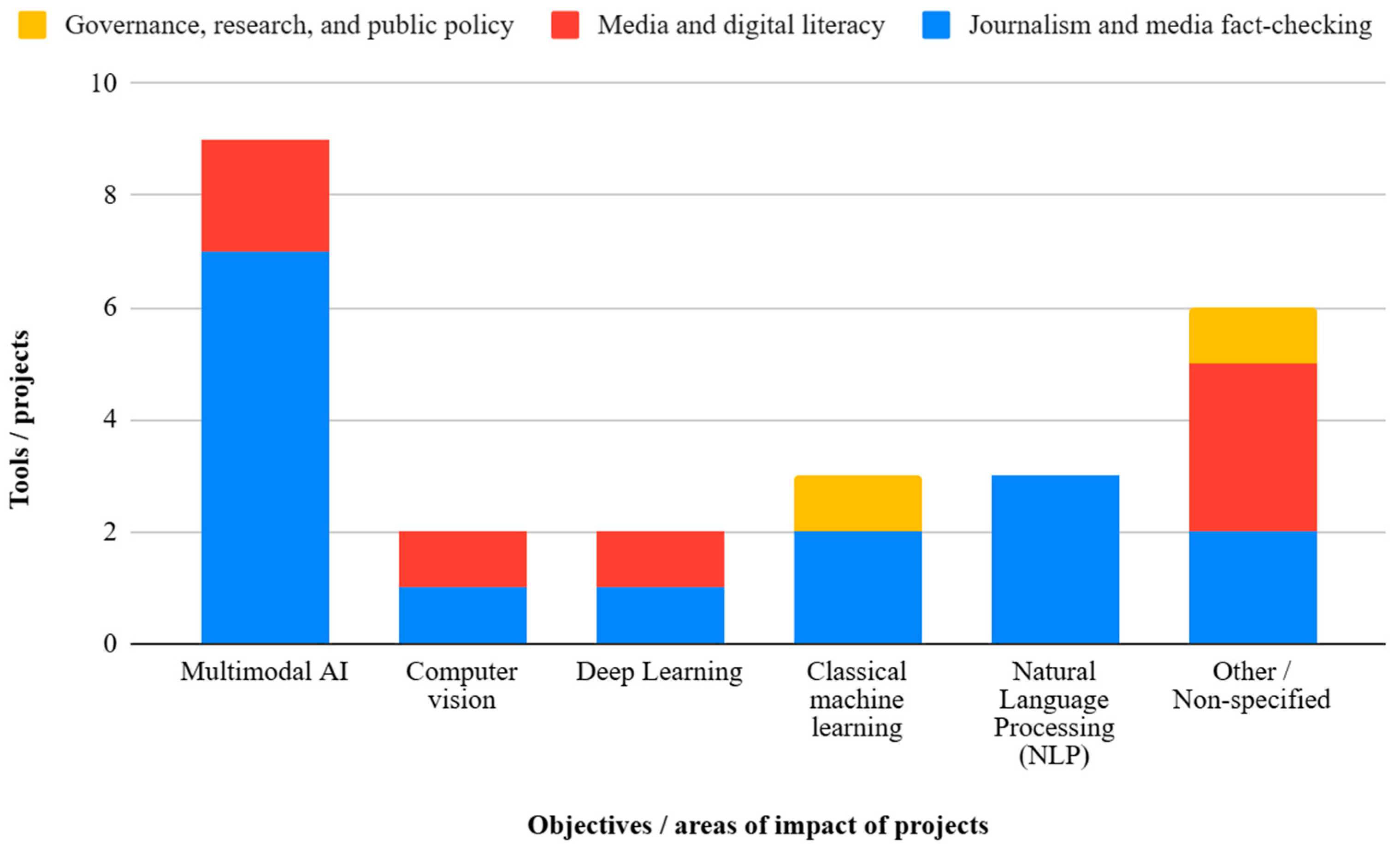

More than half of the projects (64%) apply AI as a support mechanism to automate fact-checking, cross-reference data from different sources, and prioritize potentially false content. In these systems, AI usually acts as a preliminary filter that organizes and ranks information before human review (

Figure 2). This model reinforces collaboration between algorithms and journalists—the so-called human-in-the-loop (

Santos 2023)—with the goal of enhancing efficiency without replacing critical judgment.

Until now, the fight against disinformation in Europe has been mainly led by fact-checking organizations, observatories linked to the EDMO (European Digital Media Observatory), and media and journalist associations. The lack of public momentum is due—amongst other reasons—to the absence of political consensus and of the implementation of media and informational literacy measures at either the national or regional level (

European Court of Auditors 2021).

Initiatives focused on the semi-automated verification of online content, particularly those employing multimodal AI, form the core of European efforts. Examples such as VeraAI, Reveal Image Verification Assistant, and FRAME clearly illustrate this trend. More generally, and regardless of these specific cases, these projects tend to be amongst the best funded, many supported by European Union Framework Programmes.

Projects based on deep learning often focus on detecting coordinated behavior, identifying bots, and analyzing spikes in anomalous activity. These initiatives frequently involve collaborations among universities, research centers, and technology companies, suggesting mixed funding schemes and a holistic, flow-based approach to monitoring information circulation rather than targeting specific content. The systems developed enable the identification of interaction patterns that reveal automated dynamics or structured disinformation campaigns.

Other projects aim to foster media literacy (28%). To this end, they also tend to employ multiple types of AI, including deep learning, computer vision, and multimodal systems. An illustrative example is the Hybrids project, led by the University of Santiago de Compostela (Spain), which seeks to equip researchers with the knowledge and skills required to address disinformation using NLP and deep learning tools. SOLARIS is another notable case—a multi-country initiative coordinated by Utrecht University (Netherlands) that aims to create AI-based content for citizen education.

Projects related to governance and public policy (8%) focus on developing regulatory frameworks and ethical standards aligned with the European Union’s trustworthy and responsible AI strategies. In these initiatives, AI is used as an educational resource to identify biases, explain algorithmic functioning, and strengthen citizens’ resilience to disinformation.

4.2. Stakeholders and Geographic Distribution

Geographic distribution and the kind of partnerships established are key to understanding the type of project and its degree of scalability. On the other hand, it also explains how applied research needs new evaluation mechanisms to fully understand the counter-disinformation ecosystem and to establish more effective proposals.

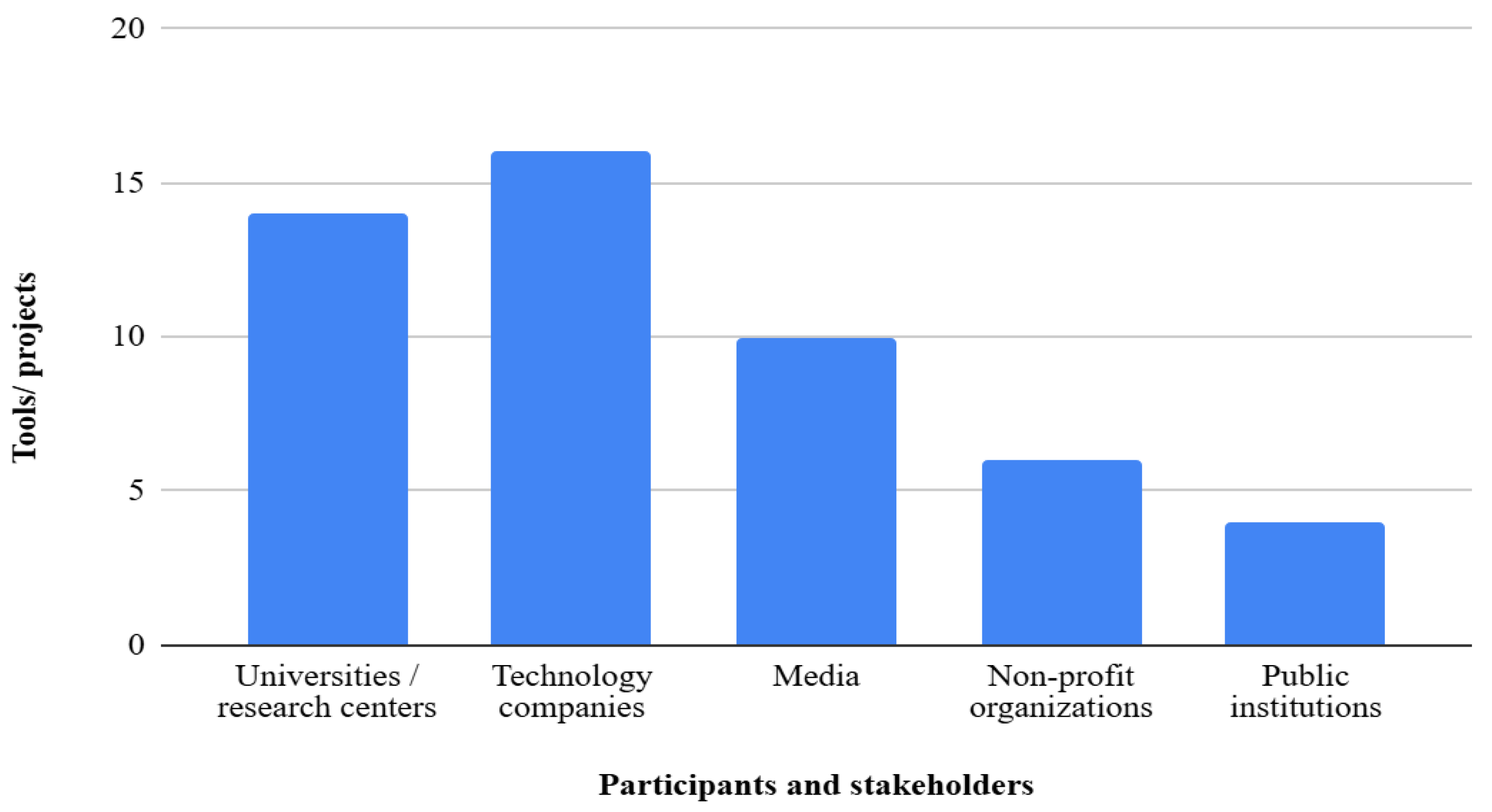

The partnerships supporting European initiatives that employ artificial intelligence to combat disinformation demonstrate a multidisciplinary structure of cooperation, often involving universities, research centers, technology companies, media organizations, civil-society groups, and public institutions. Universities and research centers participate in 14 of the 25 projects (56%) and lead more than 70% of them. Their role focuses on the technical development of AI systems, methodological validation, and the creation of ethical or governance frameworks (

Figure 3).

Compared with academic institutions, private companies participate more frequently (64%), although their leadership is nearly half as common as that of research-focused institutions. Private companies contribute technical resources and innovation expertise necessary for platform development and the deployment of algorithmic models. Their role is especially relevant in multimodal AI projects, which require advanced capacities for processing and managing large volumes of data. While their participation is essential, not all private companies involved have the same level of development or market impact; many are startups or emerging SMEs with significant potential.

Media, present in 10 projects (40%), act as spaces for experimentation and real-world validation of tools in professional news environments. Their involvement allows technological solutions to be adapted to newsroom routines and evaluated for effectiveness in verification tasks or in tracking disinformation narratives. In some cases, media organizations even lead the entire development process—from design to experimentation—as seen with the verification chatbot developed by Newtral (Spain) or TJTool, created by Diario Público to assess news quality.

Non-profit organizations (NGOs), involved in six projects (24%), play roles in social mediation and education. Their work focuses on media literacy, civic training, and raising awareness about the risks of disinformation. These entities often collaborate with universities or public institutions to ensure that results are transferred to society.

Public institutions participate in initiatives centered on AI governance and on formulating policies for information transparency. Their contributions manifest in the development of regulatory frameworks, oversight of ethical standards, and promotion of best practices in verification technologies.

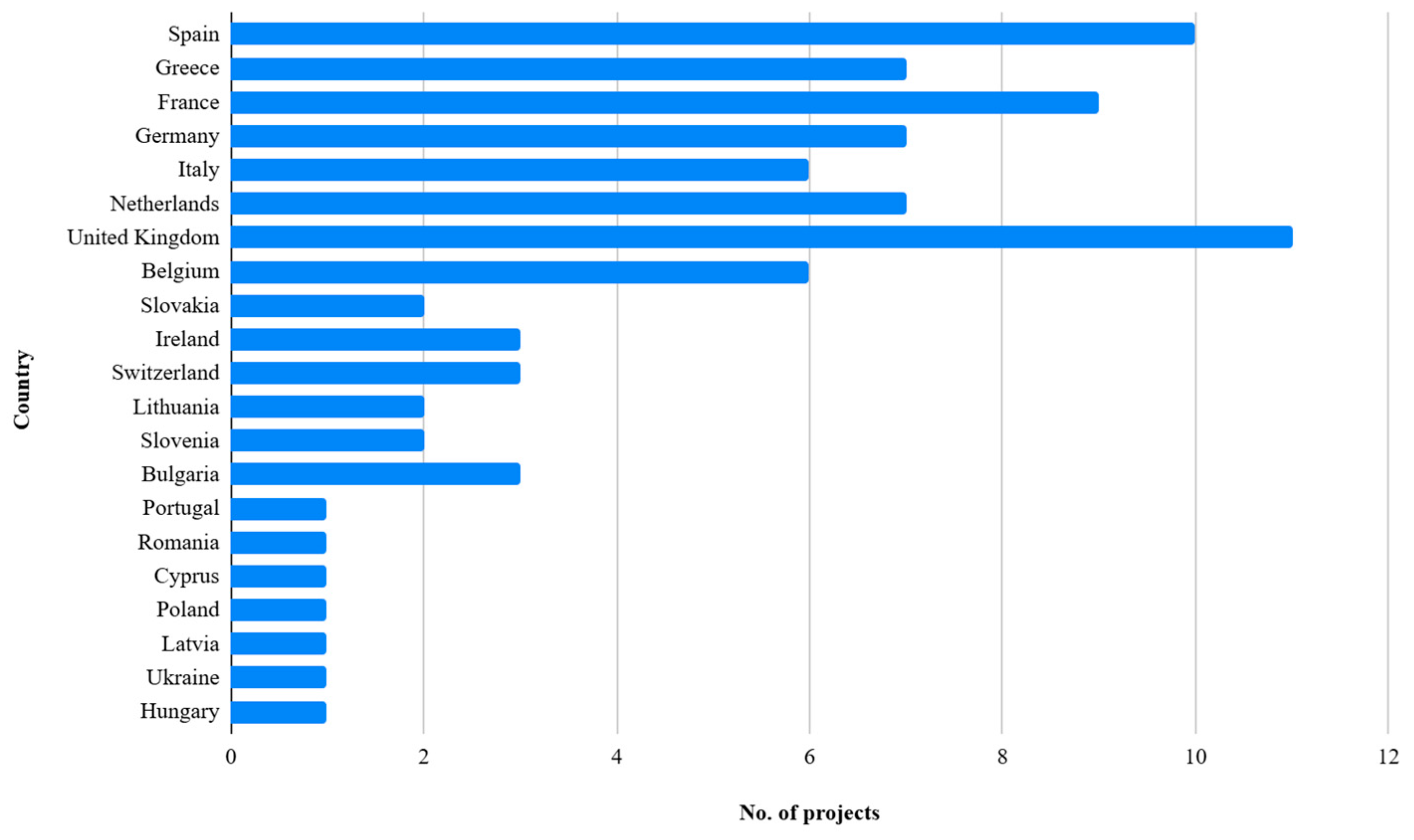

Geographically, European projects are clearly concentrated in Western and Southern Europe (

Figure 4). Spain, France, and Greece lead in the number of initiatives, followed by Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom. Amongst other reasons, this is because of the importance of fact-checking initiatives and Open-Source Intelligence (OSINT) organizations in these countries.

This pattern reflects the concentration of technological infrastructure, research centers, and European funding programs in these regions. In contrast, involvement from Central and Eastern European countries is more limited, with occasional participation that reflects territorial disparities in technological development. A strong trend toward international collaboration is also evident, as at least 13 initiatives (52%) involve multiple countries.

4.3. Funding and Budget

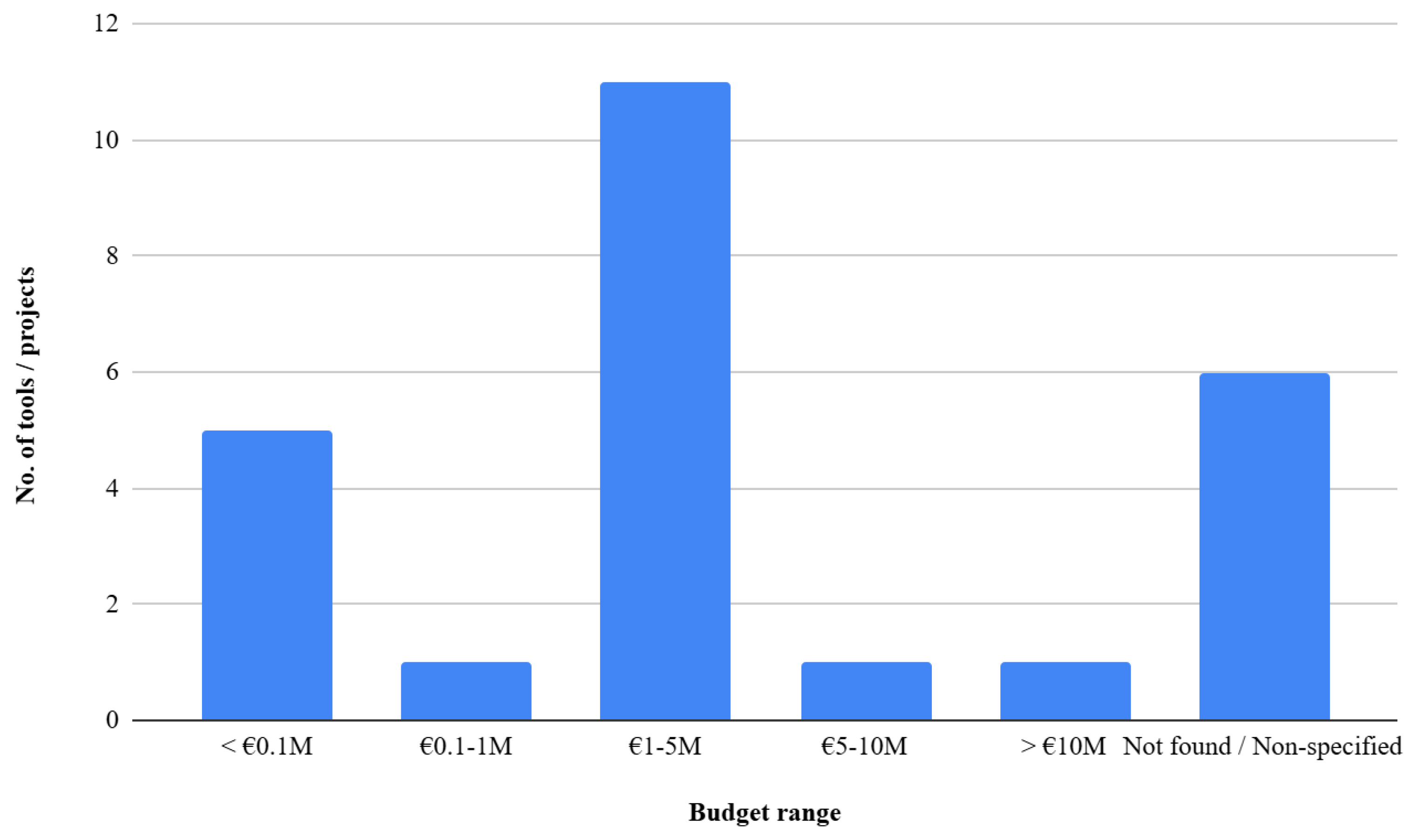

Budget ranges across the projects vary significantly. Of the 25 projects analyzed, financial information is available for 19 of them. The median funding level lies between €1 and 5 million, the range in which the largest number of initiatives is concentrated (44%). Both ends include four projects with budgets below €100,000—mainly pilot programs or short-term training activities—and one exceeding €10 million, associated with a large-scale European consortium (

Figure 5).

The absence of financial data in some projects is mainly due to heterogeneous reporting practices. Projects funded by national or European public programs tend to publish their budgets transparently, whereas private initiatives or those driven by technology companies or foundations often do not provide access to this information.

Despite these limitations, the available data allow an initial approximation of the sector’s economic scale, which combines large research programs with minor experimental or technology transfer projects.

The economic variable of these projects also allows us to understand whether they are pilot studies aiming at continuity and the need to raise the budget according to their scalability.

4.4. Diversity of Approaches in European Projects

The results of the questionnaire administered to coordinators and technical leaders of European AI-based disinformation projects confirm the breadth and diversity of approaches shaping this field’s continental landscape. The initiatives examined in more detail—VeraAI, Journalism Trust Initiative (JTI), Les Surligneurs (FRAME), and AI4Debunk—illustrate two main orientations: (1) projects focused on algorithmic development and semi-automated disinformation detection (VeraAI, AI4Debunk, and Les Surligneurs); and (2) those aimed at strengthening informational credibility through regulatory and transparency frameworks (JTI).

Testimonies gathered indicate that the practical orientation and social purpose of each project shape the type of innovation pursued, beyond technical sophistication. Denis Teyssou—AFP Medialab manager and VeraAI coordinator—emphasizes that their project focuses on developing models capable of detecting synthetic content and audiovisual falsifications.

Meanwhile, Benjamin Sabbah—director of the Journalism Trust Initiative—and Vincent Couronne—CEO of Les Surligneurs (France)—represent innovation centered on quality, traceability, and transparency. JTI proposes an ISO standard to certify editorial reliability and promote media accountability, while Les Surligneurs applies legal and linguistic analysis techniques supported by AI. According to Georgi Gotev, initiatives such as AI4Debunk (Latvia) aim to provide citizens with tools to navigate digital environments safely and make informed decisions.

This approach, conceiving AI as a support tool rather than a replacement, aligns with

Verma (

2024), who argues that automation is reshaping journalistic routines while expanding collaboration between humans and machines.

Nevertheless, despite increasing levels of algorithmic literacy and the implementation of ethical and legal guidelines, there remains a clear deficit of highly technical and specialized projects capable of responding to the fragmented nature of the European disinformation ecosystem.

4.5. Future Challenges and Europe’s Position on AI Against Disinformation

AI development in Europe faces structural and technological challenges that affect its effective application in counter-disinformation. Project coordinators identify several shared obstacles: strengthening Europe’s technological independence, improving model accuracy, reducing false positives, preventing training-data biases, and keeping pace with rapidly evolving generative technologies.

These concerns reflect a growing consensus in specialized literature warning against the risks of delegating critical judgment exclusively to automated systems (

Reyes Hidalgo and Burgos Zambrano 2025). But it mainly poses challenges to respond to the growing use of a technology that was not designed with factual accuracy as a foundational principle and that needs to rely on media as spaces for experimentation and validation.

For Denis Teyssou, one of the most pressing risks is the potential use of AI tools to fuel political polarization based on disinformation. The CEO of Les Surligneurs points to Europe’s lack of digital sovereignty and dependence on external infrastructures for data processing and storage—a vulnerability that, according to

Bontridder and Poullet (

2021), undermines scalability and long-term autonomy. Added to this is the need to strengthen media literacy and raise awareness about citizen-oriented tools, which, as Benjamin Sabbah—director of JTI—notes, are essential for building informational resilience and fostering a sustainable innovation environment.

Perceptions of Europe’s role in the global context vary between recognition and critique. Project coordinators acknowledge the EU’s efforts to promote ethical and fair AI frameworks. In this regard, Georgi Gotev states that “Europe at least tries.” However, Couronne argues that the continent “lacks ambition” and remains behind in investment and computational capacity.

In that sense, considering the current situation in which everything indicates that Defense budgets will be significantly raised, including counter-disinformation and developing AI initiatives as a fundamental variable to be included in those budgets, is urgent and necessary.

4.6. Limitations

The study presents several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. The first concerns the availability and consistency of information. Not all projects provide complete data on technical structure, budget, or outcomes, leading to uneven coverage and reduced comparability. This documentary disparity may lead to biases, particularly in the analysis of financial data.

A second limitation stems from the self-reported nature of some information collected through questionnaires. Such data depend on participants’ subjective perceptions and may reflect more aspirational than empirical views.

Finally, the exploratory and descriptive design of the study limits its ability to establish causal relationships or measure the actual impact of AI technologies in mitigating disinformation. Nevertheless, the findings offer a systematized overview of the European landscape, useful as a starting point for future research on the effectiveness and sustainability of these initiatives.

5. Conclusions

The new geopolitical context requires counter-disinformation to be included more ambitiously in the European Democracy Shield. This entails the need for higher public funding from member states and targeting EU calls towards the development of projects that respond to a geopolitical landscape of emerging conflicts and uncertainty.

Otherwise, the development of AI in the media sector raises new ethical, regulatory, and professional challenges, particularly relevant in the European context.

As

Porlezza (

2023) notes, automation and intelligent algorithms have become integrated into nearly all phases of news production—from data collection and automated writing to content personalization and distribution. This expansion, however, has sparked debate on responsibility and accountability in deploying technologies that directly affect democratic information quality. Anyways, the European landscape is particularly complex due to the many co-official languages within the EU.

There are attempts to regulate AI in the information field, especially within the European Union, where legal frameworks requiring transparency and human oversight are under discussion. Nevertheless, legal gaps and regional disparities persist, creating a regulatory mosaic with uneven application (

Reyes Hidalgo and Burgos Zambrano 2025).

In Europe, the application of artificial intelligence to fight disinformation reflects a transforming ecosystem where technological innovation, inter-institutional cooperation, and ethical commitment converge. Generally, AI-based solutions focus on automated content detection and classification and on strengthening information traceability and multilingual verification.

In parallel, the incorporation of computer-vision techniques and multimodal architectures adds a more complex dimension to detection strategies. Thus, automated verification is evolving into a more holistic approach as systems improve their ability to identify manipulated content with greater precision.

Otherwise, these projects show the integration of AI into various sectors, whether for the benefit of the public, researchers, or media professionals, and it reflects on the use of AI as a useful complement to make the whole process more effective (

Paisana et al. 2025).

In any case, we consider that this type of evaluation—such as the one conducted in this study—should be carried out by the European Union itself, with the aim of providing future calls for proposals with this prior background in their design and helping to establish a system of priorities for projects to be funded.

The collaborative structure of European projects consolidates a distributed governance model in which universities, technology companies, media organizations, civil-society groups, and public institutions play complementary roles. Academic centers lead methodological and technical development; companies contribute innovation and scalability; media organizations validate systems in professional environments; NGOs facilitate educational outreach; and public institutions shape and implement policy frameworks.

Especially considering that this intersectoral structure is organized around the principle of human monitoring, placing cooperation between algorithms and professionals at the core of the European approach. Balancing automation with human control serves as both a normative and operational axis distinguishing this model from more technocentric global approaches.

Key challenges identified by project leaders include improving model accuracy, reducing false positives, and preventing data-training biases. Structural obstacles—such as Europe’s technological dependence on external infrastructures—add to these difficulties. These limitations highlight the urgency of strengthening digital sovereignty and developing sustained support policies for innovation in verification and media literacy.

Furthermore, beyond the need to increase the number of funded projects, along with their monitoring and accountability, there is a clear deficit in terms of greater coordination and collaboration between social science and computer science research teams, both internally within universities and in the development of interdisciplinary projects.

This need is also evident in the collaboration with media organizations, especially considering that they represent one of the fundamental pillars of the EU’s strategy to defend its democracies in the coming years, as well as the most relevant actors for the practical validation of such initiatives.

In conclusion, we highlight the need for increased public funding from both Member States and the European Union for these types of projects within a geopolitical context marked by growing polarization and the redefinition of the new world order. The ultimate goal of the new strategy would be to coordinate the development of digital sovereignty with new legal frameworks while strengthening Europe’s shield against disinformation.