Exploring the Role of Conformity in Decision-Making and Emotional Regulation: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Gap and Rationale

1.2. The Literature Lacks

- A unified model integrating ER, conformity, and DM.

- Clarity on ER’s dual role as an antecedent trait influencing conformity and a situational mediator in decision-making.

- Attention to moderators, such as individual differences and cultural contexts, that shape these pathways.

Objectives

- (a)

- synthesize empirical evidence regarding the interaction between emotional regulation (ER), conformity, and decision-making (DM);

- (b)

- propose a conceptual model that captures their mediated and moderated relationships; and

- (c)

- evaluate methodological approaches to enhance theoretical precision and empirical coherence in this field.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Conceptual Foundations and Definitions

2.2. The Dual Role of Emotional Regulation

2.3. The Proposed Model: An Integrated Framework

2.4. Propositions Derived from the Model

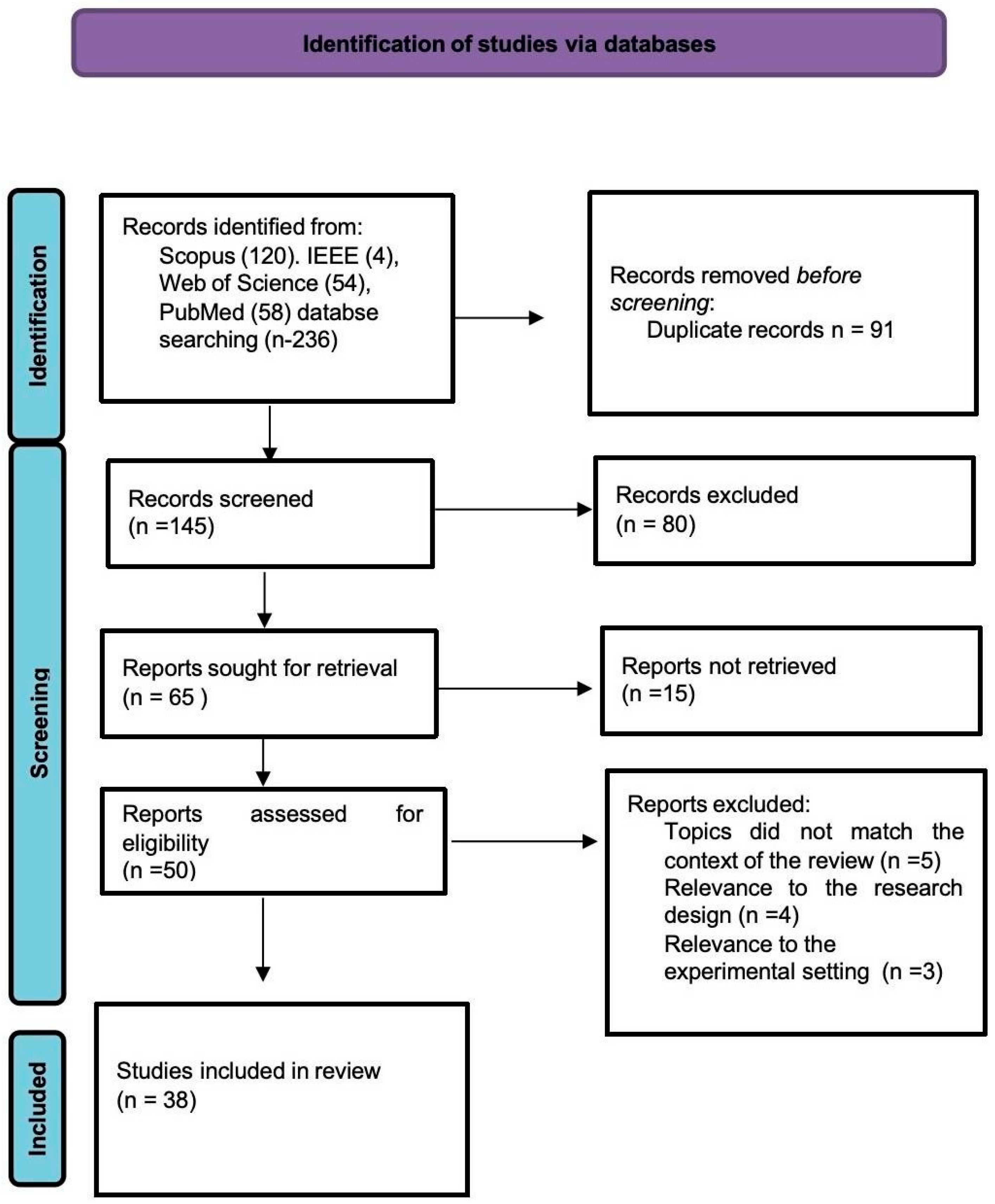

3. Methodology

3.1. Search Strategy and Study Selection

3.2. Eligibility Criteria

- Studies investigating how emotions influence conformity behaviors and their subsequent impact on decision-making processes.

- The literature search included the 2014 to 2024 timeframe to incorporate the most recent findings.

- Studies reporting experimental and observational research, case studies, meta-analyses, and systematic reviews were considered.

- Only articles published in English were included to ensure the study is broadly accessible.

- Studies that include participants of all genders and cultural ethnicities to obtain better insights on the context.

- Only articles fully accessible through institutional portals and open access were included for better accessibility.

- Articles that do not directly address the relationship between conformity, emotional regulation and decision-making.

- Studies involving any physical health issues or mental health disorders.

- Studies published before 2014 and after October 2024.

- Articles that are not open-access sources or that cannot be obtained through institutional resources.

3.3. Study Selection

3.4. Measurement and Operationalisation Across Studies

4. Results

4.1. Key Synthesis

4.2. Summary Table

5. Discussion

5.1. Conformity and Decision-Making

5.2. Conformity and Emotional Regulation

5.3. Conformity, Decision-Making and Emotional Regulation

5.4. Discussion Summary

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations

8. Future Work

- Standardize measures of emotion regulation (ER) and cognitive measures (C) and report effect sizes and contexts to facilitate cumulative research.

- Directly test the model’s propositions (P1–P8) using experimental and longitudinal designs, including manipulations of anonymity, norm tightness, and group cohesion.

- Move beyond (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic) samples by employing cross-cultural and multilevel designs to evaluate potential moderators.

- Integrate behavioral measures with physiological and neurobiological data, as well as computational modeling, to estimate the strength of the pathways (ER → C → decision-making) and the feedback from decision-making to emotion regulation (DM → ER).

- Prioritize preregistration, open data access, and a broader review of the literature, including publications in non-English languages, to minimize bias and support future quantitative syntheses.

- To address the gap identified in my systematic review, I conducted cross-cultural experiments comparing Indian and Italian participants in dynamic emotion recognition tasks. These tasks included conformity paradigms to explore how cultural background, age, and gender affect both recognition accuracy and biases. Building on these findings, my future research will extend this line of inquiry to decision-making. Specifically, I will investigate how social influence, conformity, and emotional regulation shape cognitive processes in evaluative and choice contexts.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baldi, Guido. 2014. Endogenous preference formation on macroeconomic issues: The role of individuality and social conformity. Mind & Society 13: 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, Christine, and Bruce Ferwerda. 2023. The effect of ingroup identification on conformity behavior in group decision-making: The flipping direction matters. Paper presented at the 56th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Maui, HI, USA, January 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazazi, Sepideh, Jorina Von Zimmermann, Bahador Bahrami, and Daniel Richardson. 2019. Self-serving incentives impair collective decisions by increasing conformity. PLoS ONE 14: e0224725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergquist, Magnus, and Malin Ekelund. 2025. The role of emotion regulation in normative influence under uncertainty. BMC Psychology 13: 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanchette, Isabelle, and Anne Richards. 2009. The influence of affect on higher-level cognition: A review of research on interpretation, judgment, decision making, and reasoning. Cognition & Emotion 24: 561–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocian, Konrad, Lazaros Gonidis, and Jim A. C. Everett. 2024. Moral conformity in a digital world: Human and nonhuman agents as a source of social pressure for judgments of moral character. PLoS ONE 19: e0298293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosch, Tobias, and Linda Steg. 2021. Leveraging emotion for sustainable action. One Earth 4: 1693–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Gordon D. A., Stephan Lewandowsky, and Zhihong Huang. 2022. Social sampling and expressed attitudes: Authenticity preference and social extremeness aversion lead to social norm effects and polarization. Psychological Review 129: 18–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, Glenn J., Radha Appan, Roozmehr Safi, and Vidhya Mellarkod. 2018. Investigating illusions of agreement in group requirements determination. Information & Management 55: 1071–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capozzi, Francesca, Andrew P. Bayliss, Marco R. Elena, and Cristina Becchio. 2014. One is not enough: Group size modulates social gaze-induced object desirability effects. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 22: 850–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castrellon, Jaime J., David H. Zald, Gregory R. Samanez-Larkin, and Kendra L. Seaman. 2023. Adult age-related differences in susceptibility to social conformity pressures in self-control over daily desires. Psychology and Aging 39: 102–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, Denise Dellarosa, and Robert C. Cummins. 2012. Emotion and deliberative reasoning in moral judgment. Frontiers in Psychology 3: 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deutsch, Morton, and Harold B. Gerard. 1955. A study of normative and informational social influences upon individual judgment. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 51: 629–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duderstadt, Vinzenz H., Andreas Mojzisch, and Markus Germar. 2024. Social influence and social identity: A diffusion model analysis. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 63: 1137–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Efferson, Charles, and Sonja Vogt. 2018. Behavioural homogenization with spillovers in a normative domain. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 285: 20180492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faralla, Valeria, Guido Borà, Alessandro Innocenti, and Marco Novarese. 2019. Promises in group decision making. Research in Economics 74: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germar, Markus, Thorsten Albrecht, Andreas Voss, and Andreas Mojzisch. 2016. Social conformity is due to biased stimulus processing: Electrophysiological and diffusion analyses. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience 11: 1449–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldenberg, Amit, Tamar Saguy, and Eran Halperin. 2014. How group-based emotions are shaped by collective emotions: Evidence for emotional transfer and emotional burden. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 107: 581–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, James J. 2015. Emotion regulation: Current status and future prospects. Psychological Inquiry 26: 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, Anneke, Freya Harrison, Thomas L. Norman, and Jennifer Y. F. Lau. 2014. Adolescent and adult risk-taking in virtual social contexts. Frontiers in Psychology 5: 1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, Tsutomu. 2021. Mood and Risk-Taking as momentum for creativity. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 610562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harada, Tsutomu. 2023. Exploring the effects of risk-taking, exploitation, and exploration on divergent thinking under group dynamics. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 1063525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2013. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hertz, Nicholas, and Eva Wiese. 2018. Under pressure: Examining social conformity with computer and robot groups. Human Factors: The Journal of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society 60: 1207–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hytönen, Kaisa. 2014. Neuroscientific evidence for contextual effects in decision making. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 37: 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalila, Ashraf, Salam Abdallahb, and Kundan Noor Sheikh. 2019. Fact-Checking & Social Media Sharing Behavior Among Uae Youth. In Proceedings of the International Conferences ICT, Society, and Human Beings 2019; Connected Smart Cities 2019; and Web Based Communities and Social Media 2019. Algarve: IADIS Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Diana, and Bernhard Hommel. 2015. An event-based account of conformity. Cognitive Processing 26: 484–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klucharev, Vasily, Kaisa Hytönen, Mark Rijpkema, Ale Smidts, and Guillén Fernández. 2009. Reinforcement learning signal predicts social conformity. Neuron 61: 140–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koban, Leonie, Marieke Jepma, Stephan Geuter, and Tor D. Wager. 2017. What’s in a word? How instructions, suggestions, and social information change pain and emotion. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 81: 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koriat, Asher, Shiri Adiv, and Norbert Schwarz. 2015. Views that are shared with others are expressed with greater confidence and greater fluency independent of any social influence. Personality and Social Psychology Review 20: 176–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, Jennifer S., Ye Li, Piercarlo Valdesolo, and Karim S. Kassam. 2014. Emotion and Decision Making. Annual Review Psychology 66: 799–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Li, King King Li, and Jian Li. 2019. Private but not social information validity modulates social conformity bias. Human Brain Mapping 40: 2464–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindström, Björn, Simon Jangard, Ida Selbing, and Andreas Olsson. 2017. The role of a “common is moral” heuristic in the stability and change of moral norms. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 147: 228–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipari, Francesca. 2018. This Is How We Do It: How Social Norms and Social Identity Shape Decision Making under Uncertainty. Games 9: 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackie, Diane M., and Eliot R. Smith. 2018. Intergroup emotions theory: Production, regulation, and modification of group-based emotions. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 58: 1–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistry, Prachi, and Mimi Liljeholm. 2019. The expression and transfer of valence associated with social conformity. Scientific Reports 9: 2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, Jomel W. X., Eddie M. W. Tong, Dael L. Y. Sim, Samantha W. Y. Teo, Xingqi Loy, and Timo Giesbrecht. 2016. Gratitude facilitates private conformity: A test of the social alignment hypothesis. Emotion 17: 379–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, Matthew J., Joanne E. McKenzie, Patrick M. Bossuyt, Isabelle Boutron, Tammy C. Hoffmann, Cynthia D. Mulrow, Larissa Shamseer, Jennifer M. Tetzlaff, Elie A. Akl, Sue E. Brennan, and et al. 2021. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372: n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prade, Claire, and Vassilis Saroglou. 2023. Awe and social conformity: Awe promotes the endorsement of social norms and conformity to the majority opinion. Emotion 23: 2100–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryor, Campbell, Amy Perfors, and Piers D. L. Howe. 2019. Even arbitrary norms influence moral decision-making. Nature Human Behaviour 3: 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöbel, Markus, Jörg Rieskamp, and Rafael Huber. 2016. Social influences in sequential decision making. PLoS ONE 11: e0146536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamay-Tsoory, Simone G., Nira Saporta, Inbar Z. Marton-Alper, and Hila Z. Gvirts. 2019. Herding brains: A core neural mechanism for social alignment. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 23: 174–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stallen, Mirre, and Alan G. Sanfey. 2015. The neuroscience of social conformity: Implications for fundamental and applied research. Frontiers in Neuroscience 9: 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinel, Wolfgang, Gerben A. Van Kleef, Daan Van Knippenberg, Michael A. Hogg, Astrid C. Homan, and Graham Moffitt. 2010. How intragroup dynamics affect behavior in intergroup conflict: The role of group norms, prototypicality, and need to belong. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations 13: 779–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toelch, Ulf, and Raymond J. Dolan. 2015. Informational and normative influences in conformity from a neurocomputational perspective. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 19: 579–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Yanping, and Ayelet Fishbach. 2015. Words speak louder: Conforming to preferences more than actions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 109: 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Bos, Esther, Mark de Rooij, Anne C. Miers, Caroline L. Bokhorst, and P. Michiel Westenberg. 2014. Adolescents’ increasing stress response to social evaluation: Pubertal effects on cortisol and alpha-amylase during public speaking. Child Development 85: 220–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vollmer, Anna-Lisa, Robin Read, Dries Trippas, and Tony Belpaeme. 2018. Children conform, adults resist: A robot group induced peer pressure on normative social conformity. Science Robotics 3: eaat7111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Weichs, Vivica, Nora Rebekka Krott, and Gabriele Oettingen. 2021. The self-regulation of conformity: Mental contrasting with implementation intentions (MCII). Frontiers in Psychology 12: 546178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weger, Ulrich, Stephen Loughnan, Dinkar Sharma, and Lazaros Gonidis. 2015. Virtually compliant: Immersive video gaming increases conformity to false computer judgments. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 22: 1111–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wice, Matthew, and Shai Davidai. 2020. Benevolent conformity: The influence of perceived motives on judgments of conformity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 47: 1205–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Haiyan, Yi Luo, and Chunliang Feng. 2016. Neural signatures of social conformity: A coordinate-based activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis of fMRI studies. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 71: 101–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zollman, Kevin James Spears. 2008. Social structure and the effects of conformity. Synthese 172: 317–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Core Definition (Refined) | Key Subtypes/Dimensions | Functional Role in Model | Representative Measures/Examples | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conformity | The tendency to align attitudes or behaviors with group norms or perceived expectations. | Normative: Driven by the need for social approval and avoidance of rejection. Informational: Driven by accuracy-seeking and uncertainty reduction. | Independent variable influencing Decision-Making; interacts with Emotional Regulation. | Behavioral conformity paradigms, self-report conformity scales. | Deutsch and Gerard (1955); Kim and Hommel (2015) |

| Emotional Regulation (ER) | Processes through which individuals influence the experience, expression, and modulation of emotions in social contexts. | Antecedent-Focused: Cognitive reappraisal (implemented before emotional activation). Response-Focused: Expressive suppression (implemented after emotional activation). | Dual role: (a) Trait-level ER as antecedent shaping susceptibility to conformity; (b) State-level ER as mediator influencing DM quality. | ERQ (Reappraisal/Suppression); physiological indices (e.g., PFC activation). | Gross (2015); von Weichs et al. (2021) |

| Decision-Making (DM) | Cognitive and affective processes guiding selection among alternatives under uncertainty. | Accuracy/Error • Risk Propensity • Bias Induction. | Dependent variable—outcome of conformity pathway. | Choice accuracy, risk-shift scores, response latency. | Lerner et al. (2014); Toelch and Dolan (2015) |

| Contextual Moderators | Variables that condition the strength or direction of relationships among ER, C, and DM. | Individual: Age, social sensitivity. Group: Cohesion, power hierarchy. Cultural: Collectivism, norm tightness. Technological: AI cues, anonymity, interface feedback. | Moderators affecting (a) ER → C susceptibility and (b) C → DM effect magnitude. | Contextual coding and moderator analysis across studies. | Hayes (2013); Stallen and Sanfey (2015) |

| Study (Author Year) | Methodology | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Bauer and Ferwerda (2023) | Online experiment, mixed factorial design (N = 199; UK and India). Participants curated a music playlist while 4 simulated bots voted against them 70% of the time. Measured flipping direction and group inclusiveness. | Negative flipping stronger (add → not add). Indian sample (collectivist) showed higher conformity than UK (individualist). Inclusiveness had little effect except UK negative flipping increased with inclusiveness. |

| Bazazi et al. (2019) | Spatial estimation task (N = 141). 2 × 2 design manipulating Payoff (Individual vs. Collective) and Social Information (Present vs. Absent). | Individual incentives increased harmful conformity, reducing diversity and crowd accuracy. Collective incentives preserved independence and group wisdom. |

| Bocian et al. (2024) | Preregistered Asch paradigm online (N = 120). Moral dilemma judgments alone vs. Zoom room with unanimous wrong answers by confederates. | Demonstrated moral conformity in digital settings; strangers’ unanimity shifted moral judgments. |

| Brosch and Steg (2021) | Perspective/review on leveraging emotion for sustainable action; synthesizes behavioral science and neuroscience to outline research agenda. | Emotions are central drivers of sustainable behavior. One-size-fits-all affective appeals (e.g., fear) can backfire; interventions should tailor emotions to audiences and contexts. |

| Brown et al. (2022) | Cognitive/computational Social Sampling Theory with agent-based modeling of attitude expression and polarization. | Polarization can emerge from authenticity preference, aversion to extremes, and homophily; conformity pressures scale to societal polarization. |

| Browne et al. (2018) | Field studies of 8 software development teams; analysis of designer–developer collaboration. | Conformity pressures in workshops create ‘illusions of agreement’, risking incomplete/inaccurate requirements. |

| Capozzi et al. (2014) | Modified gaze-cuing paradigm; objects cued by single vs. multiple faces. | Larger groups amplified conformity; multiple faces increased alignment of object desirability with group gaze. |

| Castrellon et al. (2023) | Mobile experience sampling (N = 157; ages 18–80) on desire regulation in social contexts. | Resistance to conformity improves with age; older adults better regulate desires amid others’ enactment, linked to emotion regulation. |

| Duderstadt et al. (2024) | Combines social identity theory with diffusion model analysis to parse in-/out-group influence on perception. | Targets whether influence acts via judgmental bias (criteria) vs. perceptual bias (sensory processing); specific empirical outcomes not provided here. |

| Efferson and Vogt (2018) | Modeling/experimental work on behavioral homogenization and norm spillovers. | Cultural evolution amplifies interventions; observed behavior change spreads via social learning beyond initial targets. |

| Germar et al. (2016) | EEG color discrimination with simulated group pressure (N = 39 women); diffusion modeling + ERP. | Conformity stems from biased evidence accumulation toward group response (drift), not lower effort; early LRP/N1 effects; increased threshold separation. |

| Goldenberg et al. (2014) | Five emotion experiments (N = 285). | Cultural differences in emotional nonconformity (β = 0.34 **). Collective emotions can drive conformity or resistance via emotional transfer/burden. |

| Gross (2015) | Review/meta-analytic synthesis using the process model of emotion regulation. | No single ‘best’ ER strategy; effectiveness is context-dependent. Future work should study sequencing/blends and move beyond single-strategy interventions. |

| Haddad et al. (2014) | Risk-taking in virtual social contexts across adolescents vs. adults. | Adolescents show heightened peer-driven risk-taking; adults more swayed by risky advice. |

| Harada (2021) | RL/Q-learning comparison of individuals, dyads, triads on a two-armed bandit. | U-shaped performance by group size; triads can outperform individuals and dyads. |

| Harada (2023) | Computational modeling of risk attitudes and explore/exploit on divergent thinking in individuals, dyads, triads. | Risk aversion positively correlated with divergent thinking, especially in triads; risk-taking did not affect dyads. |

| Hertz and Wiese (2018) | Analytical and social tasks with groups of computers, robots, or humans. | Significant conformity to non-human agents, especially in analytical tasks, tied to perceived competence. |

| Hytönen (2014) | Critical review of unconscious influence methods (priming, awareness assessment, replication). | Evidence for strong unconscious effects is weak; methodological flaws common; conscious thought likely primary driver. |

| Kim and Hommel (2015) | Attractiveness judgments under non-social numeric ‘action-like’ distraction (female participants). | Conformity-like biases can arise from basic action-representation mechanisms, not only social pressure. |

| Khalila et al. (2019) | Two urn-probability experiments (N = 48; N = 50). Private info then social info (congruency/accuracy manipulated); Brier-based incentives. | Participants underweighted social information vs. Bayesian optimality, especially when conflicting with private info; weight of social info rose as private reliability decreased. |

| Koban et al. (2017) | Systematic review on instructions/suggestions/social information impacting affect (pain/emotion) and neural correlates. | Instructions/social suggestions alter affect and neural processing via expectations/appraisals; calls for direct comparisons across influence types. |

| Koriat et al. (2015) | Non-social tasks testing ‘prototypical majority effect’; confidence and latency measures. | Perceived consensus boosts confidence/fluency absent social interaction, indicating cognitive basis for social influence. |

| Lerner et al. (2014) | Comprehensive review of emotion and decision-making; Emotion-Imbued Choice model. | Emotions (integral/incidental) pervasively shape choices via multiple dimensions and goal activation. |

| Li et al. (2019) | fMRI urn-guessing (N = 35). Private clues + 50% valid social cues; order manipulated. | Striatum updates private evidence value; dmPFC detects private–social conflict and promotes conformity; stronger striatum–dmPFC coupling predicts resistance to uninformative influence. |

| Lindström et al. (2017) | Nine experiments (N = 473) in Public Goods Game; agent-based modeling. | ‘Common is moral’ heuristic drives moral conformity; internalized values predict behavior; norms show punctuated equilibrium. |

| Mistry and Liljeholm (2019) | Gambling task (N = 30). | 72% chose suboptimal rewards to match majority (β = 0.42 **), evidencing conformity overriding reward-maximization. |

| Ng et al. (2016) | Emotion induction (N = 212); color judgment against fabricated consensus. | Gratitude increased private conformity (d = 0.62 ***), suggesting an ER pathway to social alignment. |

| Prade and Saroglou (2023) | Awe induction (N = 285). | Awe increased norm endorsement and majority conformity by ~25% (d = 0.55 ***), via reduced self-importance and collective identity. |

| Schöbel et al. (2016) | Modified urn task (N = 40) isolating informational influence; sequential decisions and confidence vs. Bayesian optimal model. | Participants overweighted private info relative to social cues, inflating confidence when in conflict—bias in info integration beyond normative pressure. |

| Shamay-Tsoory et al. (2019) | Theoretical review proposing a unified feedback-loop neural model (error monitoring, alignment, reward) for social alignment. | Different alignment forms (mimicry, conformity) share a core, rewarding mechanism. |

| Stallen and Sanfey (2015) | Review of the neuroscience of conformity. | Proposed mPFC–accumbens–insula circuitry underlying conformity; outlined fundamental and applied implications. |

| Toelch and Dolan (2015) | Neurocomputational review reframing conformity via perceptual and value-based decision models. | Clarifies normative vs. informational conformity within computational frameworks. |

| Tu and Fishbach (2015) | Studies comparing conformity to others’ actions vs. preferences (e.g., food choices). | People conform more to others’ stated preferences; conformity declines once others have acted. |

| Vollmer et al. (2018) | Robot Asch paradigm with children and adults (N = 40). | Children conformed to robots (φ = 0.41 ***); adults resisted—developmental differences in tech influence. |

| Weger et al. (2015) | Gaming + AI judgment task (N = 26). | Immersive gaming increased conformity to AI by ~1.8× (η2 = 0.32 *). |

| von Weichs et al. (2021) | Four online experiments (meta N = 789) using logical reasoning under majority misinformation; tested Mental Contrasting with Implementation Intentions (MCII) vs. controls. | MCII reduced conformity and improved accuracy (Hedges g = 0.28 [0.11, 0.46]); works with pre-specified or idiosyncratic if–then plans. |

| Wice and Davidai (2020) | Four studies (N = 808) on perceived motives for others’ conformity. | Benevolent, group-serving conformity judged positively (competent/strong); self-serving conformity judged negatively (weak-willed). |

| Wu et al. (2016) | ALE meta-analysis of fMRI social conformity studies. | Identified common neural responses to norm violations/disagreement, mapping a neural signature of social conflict. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chakraborty, S.; Milo, R.; Cordasco, G.; Perna, A.; Esposito, A. Exploring the Role of Conformity in Decision-Making and Emotional Regulation: A Systematic Review. Soc. Sci. 2026, 15, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci15010014

Chakraborty S, Milo R, Cordasco G, Perna A, Esposito A. Exploring the Role of Conformity in Decision-Making and Emotional Regulation: A Systematic Review. Social Sciences. 2026; 15(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci15010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleChakraborty, Somdatta, Rosa Milo, Gennaro Cordasco, Antonio Perna, and Anna Esposito. 2026. "Exploring the Role of Conformity in Decision-Making and Emotional Regulation: A Systematic Review" Social Sciences 15, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci15010014

APA StyleChakraborty, S., Milo, R., Cordasco, G., Perna, A., & Esposito, A. (2026). Exploring the Role of Conformity in Decision-Making and Emotional Regulation: A Systematic Review. Social Sciences, 15(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci15010014