1. Introduction

One of the most significant achievements of modern science is our understanding of population ageing as a global phenomenon, which reflects major advances in areas such as medicine, public health, and quality of life. However, this demographic shift also engenders significant social challenges, particularly with regard to the integration of older individuals into society. Despite advances in health and longevity, negative stereotypes and prejudices about the elderly remain prevalent, which has a detrimental impact on their quality of life and social participation. The World Health Organization (

WHO 2021) defines ageism as a form of prejudice that continues to prevail in various social spheres, including education, and which affects how students and teachers perceive and relate to older individuals.

In its World Report on Ageism (

WHO 2021), the WHO identifies three key strategies to combat ageism: implementing public policies that promote equality and inclusion; running educational campaigns to raise awareness and educate the general population on issues related to ageing; and promoting intergenerational contact to allow interaction and mutual understanding between generations. These measures aim to mitigate the negative effects of ageism by creating more inclusive and age-friendly environments.

Several studies have identified the most common stereotypes that young people tend to hold about older people. These include the perceptions that older people are cognitively slower, less adaptable to change, physically weak and incompetent with technology (

Cuddy et al. 2005;

Levy and Macdonald 2016). Not only do these stereotypes reinforce social exclusion and limit employment opportunities, they can also lead to internalised ageism. For instance,

Cuddy et al. (

2005) highlight that older individuals are frequently viewed as warm yet incompetent—a seemingly positive stereotype that nevertheless fosters paternalistic attitudes and marginalisation. Similarly,

North and Fiske (

2012) demonstrate how some young people view older people as a burden on economic and health systems, which can fuel intergenerational tensions.

Within the academic environment, ageism manifests in a systematic and implicit manner, affecting senior students and faculty members alike. In such an environment, discrimination is evident in the form of negative stereotypes pertaining to the health, character, and motivation of older individuals. The prevailing stereotypes concerning older adults are characterised by a tendency to associate this demographic with a perceived lack of adaptability, alongside a decline in cognitive and physical abilities, and an aversion to change. These stereotypes may manifest differently between young people and older adults. However, studies have shown that these stereotypes do not always reflect reality. Many older teachers and students continue to play an active and productive role in their academic work (

Elvira-Zorzo et al. 2025;

Fernández et al. 2018;

Jang and Heo 2020;

Matusitz and Simi 2023;

Montepare 2020;

Viana and Helal 2023).

The frequency and quality of interactions with older people, as well as knowledge of ageism, are key factors that influence levels of ageism among university students. Previous research has shown that students who have greater exposure to positive interactions with older people, either through intergenerational activities or work experience, tend to have more inclusive and less ageist attitudes towards older people (

Sasser 2024). Conversely, a more profound understanding of the ageing process and the challenges faced by older individuals has been linked to a reduction in prejudice and negative stereotypes (

Rowe et al. 2020). Studies by

Smith et al. (

2017) and

Luo et al. (

2013) have identified correlations between university students’ ageist attitudes and various factors, including limited knowledge about ageing, restricted intergenerational interaction, and the impact of sociocultural influences.

Furthermore, ageism directly influences the selection of academic career paths, acting as a disincentive for students attracted to ageing-related fields. It can also impede the integration of older students into university programmes by causing them to encounter prejudicial attitudes from their peers or professors. This influences their educational experience and their ability to adapt to the university community (

Fernández et al. 2018;

Rowe et al. 2020;

Souza et al. 2024). Thus, ageism has a twofold effect: it restricts older individuals’ access to educational opportunities and limits the diversity of perspectives they can contribute to academia.

For educators, advanced age can act as a discriminatory factor, influencing their professional and academic development. However, the assumption that older age is associated with a decline in academic productivity and the ability to adapt to new technologies and methodologies is often incorrect. Nevertheless, existing evidence appears to contradict this, showing that older teachers continue to demonstrate high levels of productivity and effectiveness. These findings thus challenge the prevailing prejudice that equates age with a decline in academic performance (

Matusitz and Simi 2023;

Viana and Helal 2023). Recent studies, including those by

Simi and Matusitz (

2016), have suggested that ageism against older students in the US can be explained by social closure theory. This theory posits that certain social groups attempt to restrict access to opportunities for others based on biases such as age.

One of the most prominent initiatives at university level is the Age-Friendly Universities (AFU) movement, which has been adopted by over 65 academic institutions worldwide. The proposal under discussion aims to promote intergenerational inclusion, education on ageing and the active participation of older people in academic life. This initiative is driven by two key objectives. Firstly, it aims to improve conditions for older students, thereby promoting a more inclusive, diverse, and age-friendly academic environment (

Bétrisey et al. 2024;

Montepare 2020;

Montepare and Farah 2020;

Montepare and Brown 2022;

Tolentino and Kakihara 2024). Secondly, it seeks to foster a culture of inclusivity, diversity, and age-friendliness within academic institutions.

Educational interventions, including short programmes, virtual courses and webinars, have been shown to effectively reduce ageism, particularly among young students. Such programmes provide students with the opportunity to become more aware of age-related biases and acquire tools to develop a deeper, less ageist understanding of ageing (

Tolentino and Kakihara 2024). Research such as that by

Hazzan et al. (

2024) has shown that university-level courses can substantially improve students’ perception of ageism. Furthermore, the study highlights the importance of implementing public policies that promote the inclusion of older students at all levels of the university system, ensuring they have access to the same educational and professional development opportunities as younger students (

Souza et al. 2024). However, despite the growing recognition of this issue, formal training in ageism remains scarce in university curricula. It is imperative that innovative pedagogical methodologies are implemented to proactively and critically address ageism in university education. A growing body of research has shown that a better understanding of ageing is linked to a reduction in negative ageist behaviour among students (

Cherry et al. 2019;

Rowe et al. 2020). Furthermore,

Scrivano and Jarrott’s (

2023) research shows that interventions aimed at reducing ageism, particularly self-directed ones, can significantly reduce adverse self-perceptions associated with age.

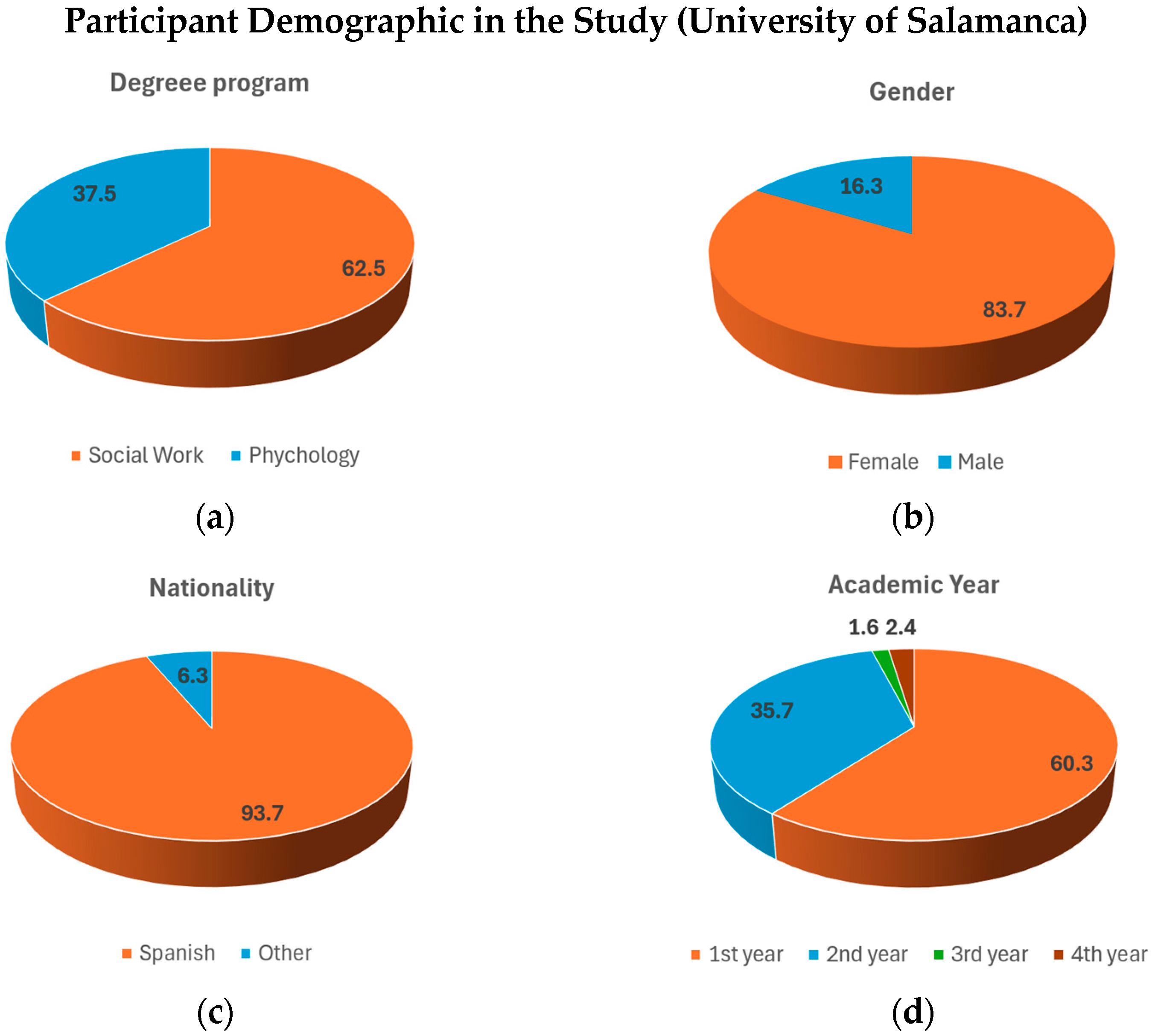

This study forms part of a broader research programme investigating the integration of active learning methods, the flipped classroom model, collaborative work and the design of intergenerational programmes (IP) in Social Psychology and Social Psychology II modules within the Psychology and Social Work degree programmes at the University of Salamanca.

The primary objective of this study is to examine attitudes towards ageing and retirement in an academic context, as well as age-related prejudices. Specifically, the study pursues the following objectives:

To identify students’ perceptions and existing stereotypes about ageing and retirement.

To evaluate changes in students’ attitudes towards older people and retirement following an educational intervention.

To assess the differential impact of the intergenerational programme on students who participate in the design of the IP compared to those who do not.

To analyse the influence of the academic degree studied (Social Work or Psychology) on perceptions of ageing, stereotypes, and attitudes towards retirement before and after the intervention.

Within this framework, the present study focuses on analysing and transforming students’ perceptions of these issues. As part of the intervention, only the students randomly assigned to the intervention group participated in the design (but not the implementation) of IPs, conceived as pedagogical and social tools.

The following hypotheses are thus proposed in this study:

H1. Participation in an educational intervention based on active methodologies (Flipped Classroom and Collaborative Work) will significantly reduce negative stereotypes towards old age in university students, in comparison with those who do not receive the intervention.

H2. The design of IP by students, as part of a training strategy explicitly aimed at promoting reflection on ageing and retirement, will reduce negative stereotypes towards retirement compared to a group that does not engage in such activity.

H3. Students who participate in the design of an intergenerational project will show a greater understanding of the concept of ageism compared to those who do not participate.

H4. The academic degree studied (Social Work or Psychology) will influence the perception of old age, stereotypes towards older people and attitudes towards retirement, both before and after the intervention.

In summary, this study aims to contribute to the social sciences by analysing a methodological proposal that seeks to transform attitudes towards old age. This proposal aims to raise awareness of the social dynamics affecting older people and promote more inclusive and equitable university environments from a generational perspective. This initiative forms part of a critical rethinking of educational processes committed to intergenerational social justice.

3. Results

This section presents the results obtained from evaluating the specific objectives set out in the study. The findings are presented separately according to the participants’ qualifications (Psychology and Social Work) and between the intervention group, which participated in the intergenerational project, and the control group, which did not. Comparative analyses of the two groups and the changes observed before and after the intervention are also included.

3.1. Objective 1: To Find out Students’ Perceptions and Previous Stereotypes About Retirement from Work

Prior to the implementation of the teaching innovation project, an analysis was conducted to examine differences in negative stereotypes of old age and negative attitudes towards retirement, as measured by the CENVE and ARS instruments, respectively, among social work and psychology students. This analysis used an independent samples t-test.

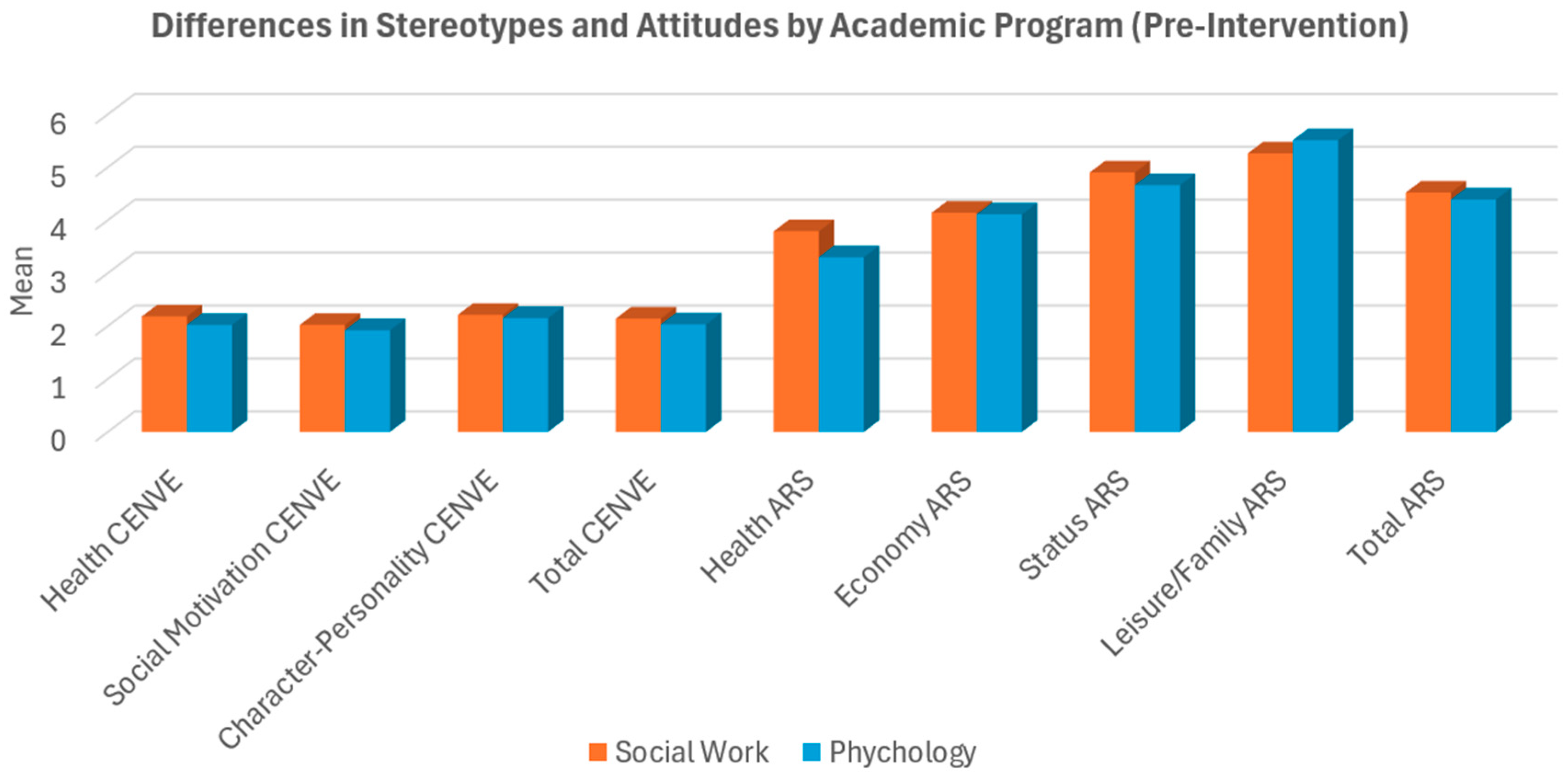

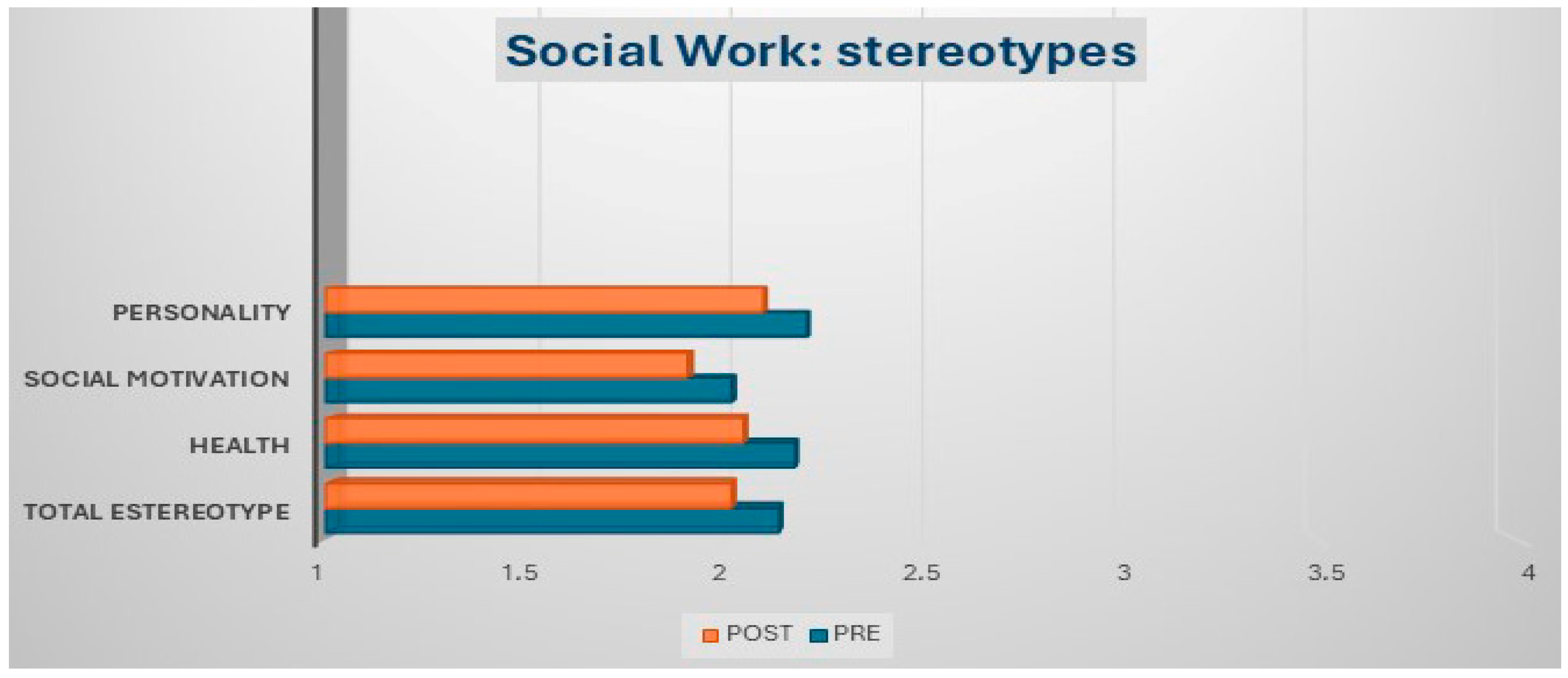

As shown in

Table 3 and

Figure 2, the findings reveal statistically significant disparities in some of the scales’ dimensions. Notably, Social Work students exhibited higher mean scores on the CENVE and ARS health factors, indicating a more negative perception of these aspects compared to Psychology students.

The results displayed in

Table 3 highlight the areas in which the two student groups differ significantly in their perceptions. Notably, social work students exhibit more negative stereotypes and attitudes relating to the health aspects of ageing and retirement, as evidenced by their higher mean scores on the relevant CENVE and ARS subscales.

Figure 2 visually summarises these quantitative differences, illustrating the contrast between the groups and reinforcing the statistical findings. This emphasises the nuanced nature of these attitudes prior to the teaching innovation intervention.

In addition, during this preliminary phase, we investigated whether significant differences existed between social work and psychology students in their interactions with both dependent and non-dependent older adults. To achieve this, we conducted an independent samples t-test.

With regard to interaction with non-dependent older people, although the effect size values (Cohen’s d) indicated a moderate to substantial effect, the t-test showed no statistically significant difference between the groups (p > 0.05). This suggests that, despite the presence of a discernible difference in effect size, it was not large enough to be statistically significant.

Regarding contact with dependent older adults, Cohen’s d values suggest a substantial and negative effect size (−0.900), indicating that psychology students have more contact with this group than social work students do. The discrepancy between the two groups is statistically significant (p < 0.05) and the size of the effect indicates that the difference between the two groups is considerable and relevant. These findings could inform the development of educational strategies and training programmes tailored to each group.

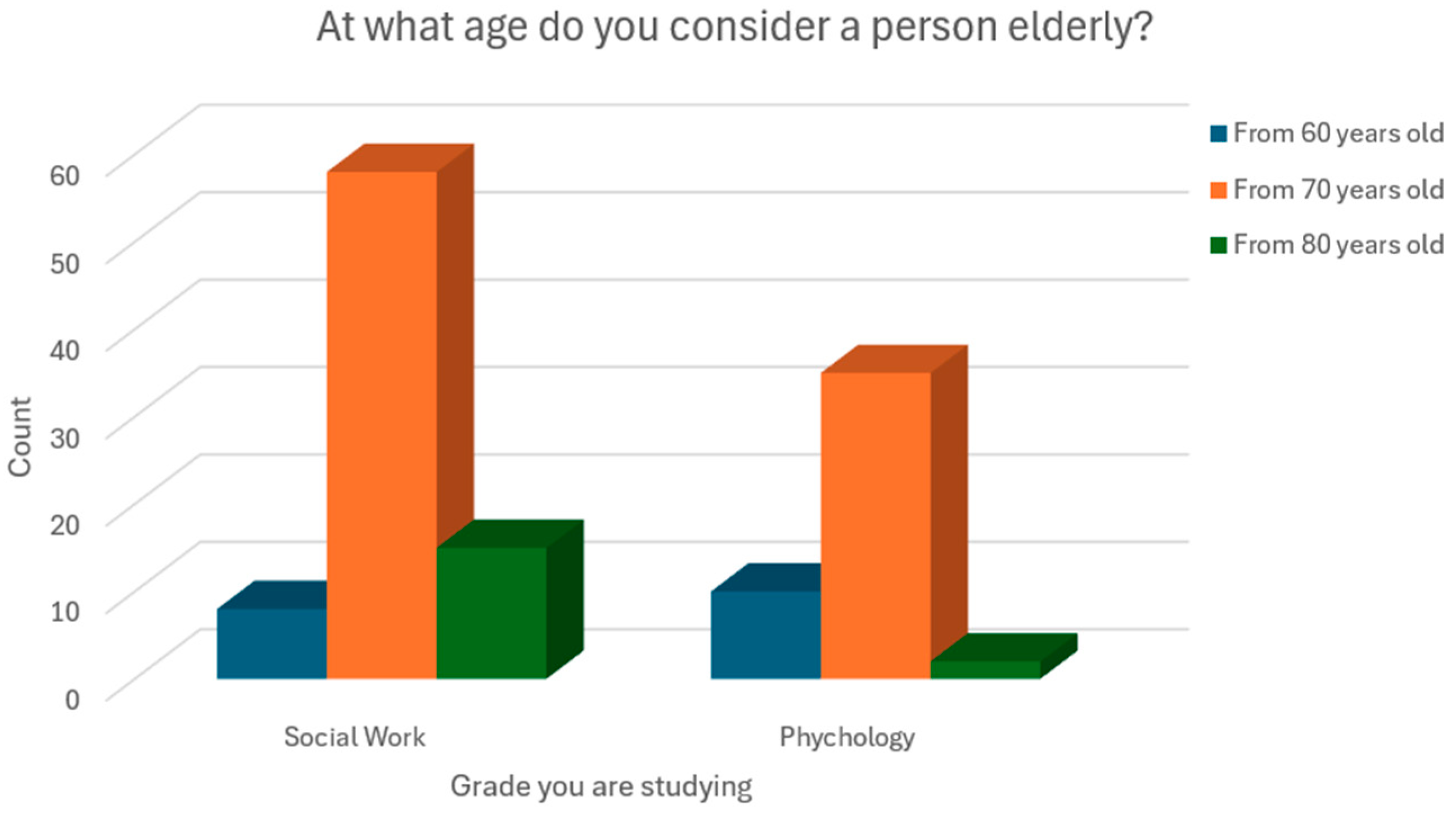

On the other hand, the relationship between the degree studied and the age at which a person is considered older was evaluated. A significant association was found between the two variables, χ

2(1) = 0.17,

p < 0.05. As shown in

Figure 3, the perception of the age at which a person is considered older differs between Social Work and Psychology students. Most Social Work students tend to consider a person as older from the age of 70 or 80, whereas Psychology students perceive a person as older from the age of 60 or 70. These findings suggest that the field of study influences the perception of old age.

On the other hand, a statistically significant, high and directly proportional correlation was found in relation to participation in the project and the ability to explain the concept of ageism (shown in

Figure 4) (

r = 0.982,

p < 0.05). This suggests a strong and significant association between the two variables. It can be seen that taking part in the innovation project helped participants to understand ageism and explain it.

3.2. Objective 2 and 3: Establish Changes in Students’ Attitudes Towards Retirement and Older People and Assess the Differential Impact of the Intergenerational Programme

This section evaluates the changes observed in the experimental and control groups before and after the intervention, as well as the differences between the groups.

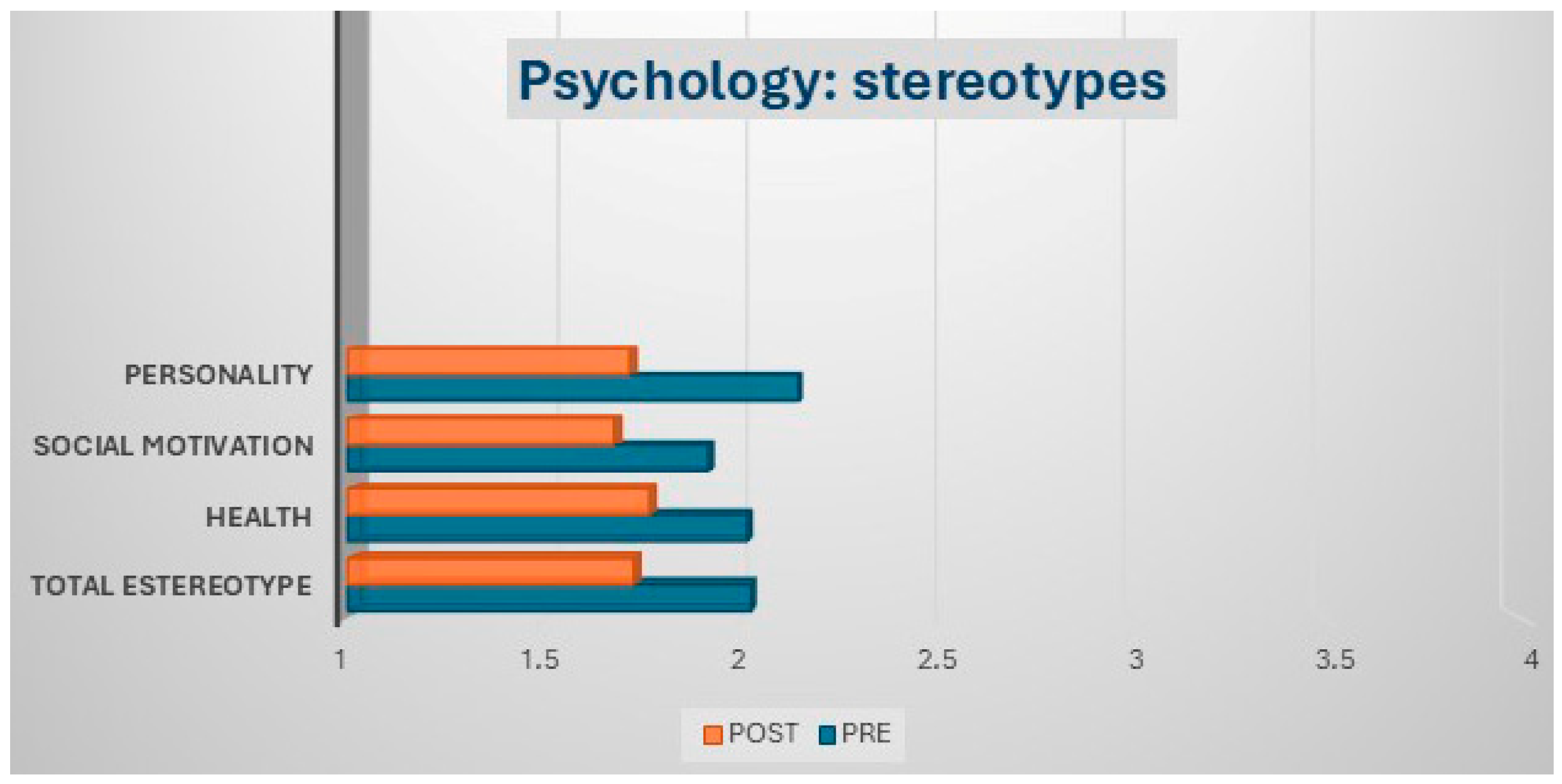

3.2.1. Results in Psychology Students

Post-intervention comparisons were made between the intervention and comparison groups. Among the psychology students who participated in the intervention group (N = 31), statistically significant reductions were observed in negative stereotypes of old age and negative attitudes towards retirement following the intervention. Specifically, the total score on the CENVE decreased from 2.03 to 1.73, t(46) = 4.47, p < 0.001, d = 0.65, and the total score on the ARS decreased from 4.39 to 4.04, t(46) = 3.54, p = 0.001, d = 0.52.

The most pronounced improvements were observed in the Health factor on both scales: CENVE Health, t(46) = 3.61, p = 0.001, d = 0.62, and ARS Health, t(46) = 8.39, p < 0.001, d = 1.22. Significant improvements were also recorded in CENVE Motivation, t(46) = 2.35, p = 0.023, d = 0.40, CENVE Character–Personality, t(46) = 3.63, p = 0.001, d = 0.71, and ARS Economy, t(46) = 2.00, p = 0.025, d = 0.29. No significant changes were observed in the Status or Family factors of the ARS in this group.

These results are illustrated by

Figure 5 and

Figure 6.

Figure 5 shows the decline in age-related stereotypes and

Figure 6 shows the reduction in retirement-related prejudices following the intervention.

By contrast, the psychology students who made up the control group (n = 16) showed no statistically significant differences in any of the variables studied between the pre- and post-intervention measurements. This finding further supports the effectiveness of the intergenerational project in causing the observed changes in the intervention group.

3.2.2. Results in Social Work Students

Post-intervention comparisons were made between the intervention and comparison groups. Significant improvements were also observed for social work students in the intervention group (N = 12) after the intervention, although to a lesser extent than in the psychology group. The total score on the CENVE showed a slight but significant reduction, t(11) = 2.45, p = 0.030, d = 0.44, and the total score on the ARS showed a moderate improvement, t(11) = 2.13, p = 0.048, d = 0.39.

The most notable changes were observed in ARS Health, t(11) = 4.65, p < 0.001, d = 0.91, and CENVE Character–Personality, t(11) = 2.71, p = 0.020, d = 0.56. No significant changes were found in the Status, Family, or Economic factors of the ARS in this group.

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 illustrate these findings by showing how retirement-related prejudices and age-related stereotypes declined following the intervention among the group of social work students.

As in Psychology, there were no significant differences between pre- and post-intervention measurements in the Social Work control group (N = 11). This confirms that the positive changes observed in the Social Work intervention group can be attributed to the intervention itself.

3.3. Overall Comparisons and Summary of Results

A paired-sample

t-test was performed to compare the pre- and post-intervention scores of the total intervention group (N = 85), which included students from both degree programmes. The results are presented in

Table 4.

As shown in

Table 4, the results indicate a significant decrease in negative stereotypes about old age, as well as in some dimensions of retirement attitudes, following the intervention. These differences were statistically significant in the total scores of the CENVE and ARS instruments, as well as in the Health and Motivation factors of CENVE and the Health factor of ARS (

p < 0.001). Effect sizes (Cohen’s

d) ranged from 0.57 to 1.45, indicating moderate to large effects depending on the variable.

An independent samples

t-test was then performed to compare the post-intervention scores of Social Work (N = 54) and Psychology (N = 31) students who participated in the intergenerational project. The results are presented in

Table 5.

As shown in

Table 5, there were significant differences between Social Work and Psychology students in the CENVE Total, CENVE Health, CENVE Motivation, CENVE Character-Personality and ARS Health dimensions after the intervention. Psychology students scored lower on stereotypes and negative attitudes (

p < 0.05). Effect sizes ranged from 0.46 to 0.85, indicating small to large effects.

In contrast, in the general comparison group (N = 40), significant differences were observed in only a few variables: a significant increase in the ARS Health factor, t(39) = 8.56, p < 0.001, and a significant decrease in the ARS Status factor, t(39) = −2.00, p = 0.026. Furthermore, the differences between Social Work and Psychology students in the comparison group were not significant for most of the variables studied.

In summary, the data suggest that the intergenerational project intervention was effective in reducing stereotypes and prejudices relating to old age and retirement, particularly with regard to health. These changes were consistent among students in both degree programmes, although they were more pronounced in some areas among psychology students. These findings emphasise the importance of incorporating innovative methodologies into university education to promote more empathetic, informed, and positive attitudes towards older people and ageing.

In addition to the overall effects of the intervention, specific focus was placed on the role of student participation in designing the IP as an active pedagogical strategy aimed at encouraging reflection on ageing and retirement. The intervention group, who engaged in designing the IP, showed a more significant reduction in negative retirement stereotypes, as measured by the ARS, than the control group who did not participate in this activity. This finding suggests that actively involving students in the conceptualisation and planning of the IP significantly challenges and transforms their preconceived attitudes about retirement, thereby supporting the second hypothesis (H2) of the study.

3.4. Objective 4: Influence of Academic Degree on Perceptions and Attitudes Towards Ageing and Retirement Before and After the Intervention

This objective analysed how the academic degree (Social Work or Psychology) influences perceptions, stereotypes, and attitudes towards ageing and retirement before and after participating in the intergenerational intervention.

Before the intervention, significant differences were found between the two groups of students, particularly with regard to stereotypes and attitudes relating to health. In this area, Social Work students displayed more negative perceptions than Psychology students.

Following the intervention, both groups improved their perceptions and attitudes; however, Psychology students maintained significantly higher scores on the total CENVE scale and its subdimensions (Health, Motivation and Character/Personality), as well as on the Health dimension of the ARS. This indicates that the type of academic degree continues to influence the intensity and scope of the change achieved.

These results suggest that to maximise the impact of educational and intergenerational interventions, strategies should be adapted to the specific characteristics and preconceptions of each academic group.

Furthermore, the results can be interpreted in terms of social closure theory. Age discrimination can be viewed as a mechanism that maintains boundaries by restricting opportunities and reinforcing social hierarchies between age groups. The reduction in negative stereotypes observed in this study suggests that active intergenerational approaches can counteract these processes by promoting inclusive relations between different age groups and challenging practices that disadvantage older people.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study provide substantial evidence that ageism is a pervasive form of discrimination in university settings, as previously observed by the World Health Organization (

WHO 2021),

North and Fiske (

2012), and

Levy and Macdonald (

2016). As the study progressed, it became clear that negative stereotypes about older adults were widespread, particularly with regard to health, motivation, and character. These findings are consistent with those reported by

Jang and Heo (

2020),

Matusitz and Simi (

2023) and

Viana and Helal (

2023), who also noted the prevalence of ageist attitudes among students and university faculty.

In relation to H1, the statistically significant changes observed after the intervention (a decrease in negative stereotypes of old age, as measured by the CENVE and ARS) confirm the effectiveness of the active methodologies employed, such as the flipped classroom approach and collaborative work based on designing intergenerational programmes. These results are consistent with previous research showing that well-structured educational interventions can reduce ageism among university students (

Tolentino and Kakihara 2024;

Rowe et al. 2020;

Cherry et al. 2019). Furthermore, the substantial effect sizes (with some d values exceeding 0.70) emphasise the transformative potential of these methodologies in training future professionals to be sensitive to the realities of population ageing.

This impact suggests that it is not just a one-off cognitive change, but a substantial transformation in students’ social perception of ageing and retirement. Direct interaction with older people, critical reflection encouraged by the flipped classroom approach, and active involvement in designing intergenerational projects appear to have initiated a process of destabilisation and reconfiguration of established mental frameworks traditionally associated with negative perceptions of ageing.

Furthermore, these results reinforce the pedagogical value of experiential and immersive methodologies that transform as well as inform. The intervention did more than impart knowledge; it created meaningful experiences with the potential to generate critical awareness, empathy, and professional commitment. This is particularly relevant in the context of training future social and psychological professionals, for whom relationships with older people will be an important part of their practice.

Therefore, the results related to H1 support the systematic incorporation of innovative teaching strategies into university training programmes as a means of combatting generational prejudices and of training more competent, humane and committed professionals to address the reality of demographic ageing.

In relation to H2, while no statistically significant changes were observed across all dimensions of the ARS, a specific improvement was noted in how health is perceived in relation to retirement. This result partially supports the hypothesis that educational interventions modify not only general stereotypes about old age, but also attitudes towards specific stages of the life cycle, such as retirement.

This improvement can be attributed to the students’ exposure to materials that emphasise positive and active ageing, and to their interaction with real-life examples during the intergenerational project design process. As

Montepare (

2020) and

Montepare and Brown (

2022) point out, such activities encourage a critical re-evaluation of previous beliefs, enabling young people to challenge the internalised stigma surrounding deterioration and passivity associated with retirement.

However, the lack of significant improvements in other dimensions of ARS (such as those related to status or economics) may be due to several factors. Firstly, these beliefs may be more deeply rooted in culture and therefore require longer interventions or more direct components to address them. Secondly, these dimensions may not have been sufficiently activated during the intervention as they were not among the central themes of the proposed materials or activities.

These findings suggest that future editions of the programme should include materials or activities that explore issues such as the social value of retired people, their economic contribution, and how they spend their free time. This would generate a broader impact on the different dimensions of attitudes towards retirement.

Thus, H2 is partially confirmed: the intervention has proven effective in modifying certain key perceptions (such as those relating to health), but a more specific and comprehensive design is required to have a significant impact on all the dimensions assessed by the ARS.

Regarding (H3), the strong positive correlation between participation in the project and improvement in conceptual understanding of ageism (r = 0.982, p < 0.05) is a highly relevant finding. This result suggests that students exposed to the intervention not only changed their attitudes but also built a more solid, conscious and critical understanding of the phenomenon of ageism. Unlike a simple attitudinal change, this type of deep understanding involves the internalisation of the social, cultural and structural mechanisms that perpetuate age discrimination.

As documented by previous research (

Sasser 2024;

Rowe et al. 2020;

Cherry et al. 2019), this type of meaningful learning is crucial, as greater awareness of ageism is associated with a lower likelihood of reproducing it in both personal and professional contexts. In other words, simply being non-discriminatory is not enough; it is also necessary to understand ageism as a normalised system of oppression that needs to be identified and actively challenged.

In this regard, the impact of the intervention also reinforces the World Health Organization (

WHO 2021) approach, which identifies education as one of three key strategies for combating ageism, alongside public policy and intergenerational contact. From this perspective, the educational programme developed in this study not only demonstrates its effectiveness in training, but also its potential to promote social justice by training future professionals to detect and question discriminatory practices towards older people in various areas, such as health, social services and the media.

Furthermore, the high correlation coefficient observed (close to 1) suggests that the change is not merely incidental or superficial, but reflects a direct and powerful association between educational experience and critical learning. This supports the continued integration of this type of intervention into university curricula, particularly in degree programmes such as Psychology and Social Work, which play a pivotal role in caring for an ageing population.

Therefore, H3 is fully confirmed, and its implications extend beyond academia: they highlight the need to promote a professional culture that is sensitive to, informed about, and actively committed to eradicating ageism.

The results relating to H4 fully support the hypothesis in both the pre- and post-intervention phases. Initial differences observed between psychology and social work students, particularly with regard to negative attitudes towards old age linked to health, confirm that disciplinary fields influence perceptions of ageing, as previously noted by

Iversen et al. (

2009) and

Fernández et al. (

2018). These differences imply that the theoretical and epistemological frameworks of each degree programme influence how future professionals conceptualise ageing and retirement.

The greater reduction in stereotypes observed among psychology students after the intervention suggests that this group was probably more receptive to the methodology used due to their familiarity with processes of self-reflection, bias analysis, and critical thinking. This finding is consistent with

Cherry et al.’s (

2019) proposal that prior exposure to content on ageing and the curricular context are key moderating factors affecting the effectiveness of educational interventions against ageism.

Interestingly, although psychology students reported having more contact with dependent older people, they had less negative perceptions than social work students. One possible explanation for this is that the frequency and quality of contact are both decisive factors in shaping attitudes (

WHO 2021;

Sasser 2024;

Rowe et al. 2020). In psychology, interactions with dependent older people tend to occur in clinical or reflective learning settings, which may prevent negative stereotypes from being activated. By contrast, social work students, despite having less direct contact, may be more influenced by structural representations of old age associated with vulnerability and social exclusion (

Cuddy et al. 2005;

North and Fiske 2012;

Levy and Macdonald 2016;

Luo et al. 2013;

Smith et al. 2017). This could explain their more negative responses in the CENVE and ARS.

By contrast, the lack of significant improvements in the control group highlights the importance of systematically integrating ageing-related content into university curricula. While the social significance of ageing is increasingly recognised, there are still few formal opportunities to address ageism from a critical perspective (

Iversen et al. 2009;

Levy and Macdonald 2016). Without such training, future professionals may struggle to intervene ethically and effectively in the social challenges associated with population ageing.

In this sense, the findings align with the proposals of the international Age-Friendly Universities (AFU) initiative, which not only promotes the inclusion of older people in university life, but also the creation of more equitable, accessible, and intergenerational environments (

Bétrisey et al. 2024;

Montepare and Farah 2020). Adopting this institutional philosophy would enrich the education of young students through a more holistic approach and empower older people by recognising their active role as educational agents rather than merely recipients of services.

For these reasons, the results of this study reinforce the idea that educational interventions based on active methodologies have high transformative potential in mitigating ageism and fostering more favourable attitudes towards old age and retirement. However, this positive impact depends on rigorous design and implementation. Beyond the immediate impact, the study highlights the urgent need to incorporate ageing-related content across the board in higher education, as proposed by

Souza et al. (

2024) and

Tolentino and Kakihara (

2024). This pedagogical strategy is essential for training professionals who are both ethically and socially committed and capable of facing the challenges of an ageing society.

Limitations

When interpreting the results of this study, it is important to consider the following limitations. Firstly, the sample was limited to psychology and social work students from a single university, which restricts generalisation to other contexts. Future research should expand the range of disciplines and institutions involved.

In methodological terms, while the design followed a quasi-experimental pre-test–post-test format with a non-equivalent comparison group, the evaluation was limited to short-term effects. Therefore, the study cannot be considered a longitudinal design in the strict sense, as no follow-up measurements were included to examine whether the changes were sustained over time. Future research should incorporate medium- and long-term assessments to analyse the permanence of the observed effects.

The non-random assignment of groups, a characteristic of quasi-experimental designs, may have introduced selection biases. Implementing randomised controlled trials in future studies would strengthen internal validity.

Another limitation concerns the composition and size of some subgroups in the sample. The predominance of female students reflects the gender distribution typically found in psychology and social work programmes, which may limit the representativeness of the results. Additionally, certain subsamples were small, and some Cronbach’s alphas were modest, which may affect the reliability and stability of the findings. Future research should address these issues by recruiting larger and more diverse samples.

Finally, the inclusion of multiple methodological components meant that it was not possible to determine the specific impact of each one. Analysing their differential effect would allow future interventions to be optimised.

Despite these limitations, the study provides valuable evidence of the effectiveness of active and intergenerational methodologies in combatting ageism, and establishes a robust foundation for future research.

5. Conclusions

The findings of this study provide solid evidence of the widespread presence of ageism in the university environment, which is consistent with the findings of the World Health Organization (

WHO 2021) and other relevant authors. Negative stereotypes about older people, particularly with regard to health, motivation and character, are deeply rooted among students, reflecting a widespread issue that requires educational attention.

Interventions based on active methodologies, such as the flipped classroom approach and collaborative work on intergenerational project design, were effective in significantly reducing negative stereotypes about old age, thus confirming hypothesis 1. This change was not merely superficial but involved a profound reconfiguration of the social perception of ageing and retirement. This was facilitated by direct interaction with older people and critical reflection.

Although hypothesis 2 was partially confirmed, with improvements observed in health perceptions in retirement, no significant changes were observed in other aspects, such as status and the economic dimension. This suggests the need for more specific and comprehensive future interventions that address all dimensions of attitudes towards retirement holistically.

Hypothesis 3 was fully confirmed, demonstrating a strong correlation between participation in the project and the development of a critical and conscious understanding of ageism. This deep learning is essential for training professionals who will not only avoid discriminatory behaviour, but also actively question and challenge the social structures that perpetuate age discrimination.

Finally, hypothesis 4 was confirmed by evidence of differences between psychology and social work students before and after the intervention, highlighting the impact of the disciplinary framework on perceptions of ageing. The greater receptivity of psychology students suggests that curriculum content and prior experience are important factors in the effectiveness of educational interventions.

Taken together, these results highlight the importance of systematically incorporating content on ageing and ageism into university curricula and adopting active teaching methods that encourage ethical, critical and socially just learning in the context of an ageing population. Similarly, the importance of creating an inclusive and welcoming university environment for people of all ages is emphasised, one that fosters intergenerational dialogue and respect for age diversity.