Exploring Economic and Risk Perceptions Sparking Off-Shore Irregular Migration: West African Youth on the Move

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

Theory of Reasoned Action and the Cultural Theory of Risk Perception

3. Literature Review

3.1. Arguments and the Discourse for Economic and Risk Perceptions Which Lead to Off-Shore Irregular Migration

3.2. Migration as a Means of ‘Insurance’ Which Sparks Off-Shore Irregular Migration

3.3. Salary Disparities Between Africa and Western Nations Sparks Off-Shore Irregular Migration

3.4. Peer Pressure and Community Influences Spark Off-Shore Irregular Migration to CODs

3.5. Personal and Social Factors’ Influence on Undertaking Irregular Migration

3.6. Economic Freedom Perceptions Serve as a Pull Factor for Off-Shore Irregular Migration

3.7. Perceived Existence of Welfare Payments to All Residents in the Developed Nations

3.8. Risk Perceptions and West African Youth Decision Making to Embark on Irregular Migration Processes

3.9. Safety and Protection Perceptions About Irregular Migrants’ Disappearance to Unknown Destinations

3.10. Spiritual Beliefs in a Higher Power for Protection During Off-Shore Irregular Migration

3.11. Benefits of Host Nations’ Return and Non-Return of Irregular Migrants

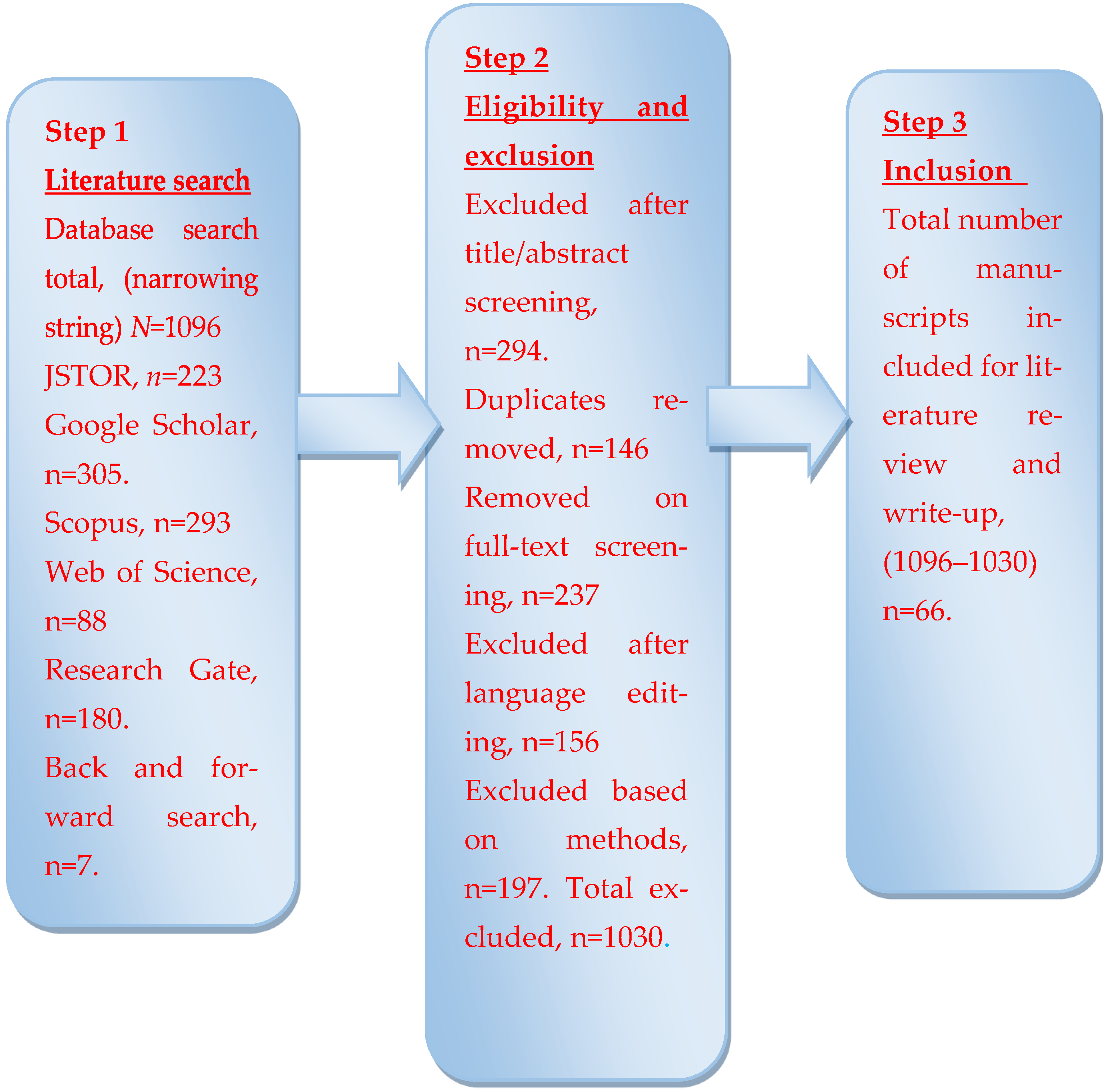

4. Research Methodology

5. Research Findings

5.1. Migration as a Means of Insurance and Livelihood Strategies Sparks Irregular Migration

5.2. Salary Disparities and Better Opportunities Motivate Irregular Migration

5.3. Peer Pressure and Community Influences Spark Off-Shore Irregular Migration

5.4. Economic Freedom Perceptions Serve as a Pull Factor Which Motivates Irregular Migration

5.5. Perceived Existence of Welfare Payments to All Residents in Developed Nations

5.6. Safety and Protection Perceptions Against the Reality of Irregular Migrants’ Disappearance

5.7. Irregular Migrants’ Spiritual Beliefs in Higher Power for Protection During Migration

5.8. Benefits of Host Nations’ Return and Non-Return of Irregular Migrants

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdile, Mahdi, and Päivi Pirkkalainen. 2011. Homeland perception and recognition of the diaspora engagement: The case of the Somali diaspora. Nordic Journal of African Studies 20: 23–23. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, Icek, and Martin Fishbein. 1988. Theory of reasoned action-Theory of planned behavior. University of South Florida 2007: 67–98. [Google Scholar]

- Akpan, Nseabasi S., and Emmanuel M. Akpabio. 2003. Youth restiveness and violence in the Niger Delta Region of Nigeria: Implications and suggested solutions. International Journal of Development Issues 2: 37–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Suqri, Mohammed Nasser, and Rahma Mohammed Al-Kharusi. 2015. Ajzen and Fishbein’s theory of reasoned action (TRA) (1980). In Information Seeking Behavior and Technology Adoption: Theories and Trends. Hershey: IGI Global Scientific Publishing, pp. 188–204. [Google Scholar]

- Ankomah, Kwadwo. 2022. Cultural Adherence, Personal Financial Behaviour and Investment Decision Making. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Cape Coast, Cape Coast, Ghana. [Google Scholar]

- Baada, Jemima Nomunume, Bipasha Baruah, and Isaac Luginaah. 2019. ‘What we were running from is what we’re facing again’: Examining the paradox of migration as a livelihood improvement strategy among migrant women farmers in the Brong-Ahafo Region of Ghana. Migration and Development 8: 448–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin-Edwards, Martin. 2008. Towards a theory of illegal migration: Historical and structural components. Third World Quarterly 29: 1449–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, Timothy. 2002. Restricted access to markets characterizes women-owned businesses. Journal of Business Venturing 17: 313–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, John W. 2013. Steps in Conducting a Scholarly Mixed Methods Study. Lincoln: University of Nebraska-Lincoln. [Google Scholar]

- Crush, Jonathan. 2019. The problem with international migration and sustainable development. In Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. London: Routledge, pp. 85–99. [Google Scholar]

- Dangarembwa. 2019. Noel. Searching for “Greener Pastures”: A Narrative Study of the Livelihood Experiences of Zimbabwean Migrants with Disabilities in South Africa. Ph.D. dissertation, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva, Rebelo, Maria José, Mercedes Fernández, and Carmen Meneses. 2021. Societies’ hostility, anger and mistrust towards Migrants: A vicious circle. Journal of Social Work 21: 1142–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, S. Landes. 2024. Why Are We So Rich and They So Poor? In Developing Areas. London: Routledge, pp. 74–85. [Google Scholar]

- Dennison, James. 2022. Re-thinking the drivers of regular and irregular migration: Evidence from the MENA region. Comparative Migration Studies 10: 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deotti, Laura, and Elisenda Estruch. 2016. Addressing Rural Youth Migration at Its Root Causes: A Conceptual Framework. Rome: FAO. [Google Scholar]

- DESA. 2008. National Development Strategies. In Policy Notes. New York: United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, Mary, and Aaron Wildavsky. 1982. How can we know the risks we face? Why risk selection is a social process 1. Risk Analysis 2: 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliseev, Alex, Rolf Maruping, Daryl Glaser, Noor Nieftagodien, Stephen Gelb, Devan Pillay, Loren Landau, David Coplan, Julia Hornberger, Melinda Silverman, and et al. 2008. Go Home or Die Here: Violence, Xenophobia and the Reinvention of Difference in South Africa. New York: NYU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Erdal, Marta Bivand. 2022. Migrant transnationalism, remittances and development. In Handbook on Transnationalism. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 356–70. [Google Scholar]

- Etika, David Nandi, Jacob U. Agba, and Robert VIctor Opusunju. 2018. Communication manipulation and public perception of religiosity, migration and refugee crisis in Nigeria. Adhyatma: A Journal of Management, Spirituality, and Human Values 2: 14. [Google Scholar]

- European Union Parliamentary Assembly. 2006. Debates of European Parliament. September 5. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/CRE-6-2006-09-05_EN.html (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Fonju, Njuafac Kenedy. 2024. Historical Challenges of Alarming Deadly Illegal Migration Crossing of African Youths Across the Sahara Desert–Mediterranean-Atlantic Pathways Versus Accelerated British Diplomacy of Illegal Migration Bill Facing Upright Internal and External Rejections of the Post-COVID-19 of the 21st Century. Journal of Arts Humanities and Social Sciences 3: 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, Denis. 2015. The Formation of an EU-Based CSO: A Case Study of the Platform for International Cooperation on Undocumented Migrants. In EU Civil Society: Patterns of Cooperation, Competition and Conflict. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 155–72. [Google Scholar]

- Frouws, Bram, Melissa Phillips, Ashraf Hassan, and Mirjam Twigt. 2016. Getting to Europe the WhatsApp Way: The Use of ICT in Contemporary Mixed Migration Flows to Europe. Regional Mixed Migration Secretariat Briefing Paper. Nairobi: Regional Mixed Migration Secretariat. [Google Scholar]

- Ghana Statistical Service. 2024. Available online: https://statsghana.gov.gh/gssmain/storage/img/infobank/Ghana%20Statistical%20Service%202024%20Releases%20-%20online.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Harper, Annie, Michaella Baker, Dawn Edwards, Yolanda Herring, and Martha Staeheli. 2018. Disabled, poor, and poorly served: Access to and use of financial services by people with serious mental illness. Social Service Review 92: 202–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikuteyijo, Lanre Olusegun. 2020. Irregular migration as survival strategy: Narratives from youth in urban Nigeria. In West African Youth Challenges and Opportunity Pathways. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 53–77. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2018. Africa Migration Report: Second Edition. Available online: https://publications.iom.int/books/africa-migration-report-second-edition (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Inyama, Joseph. 2021. Economic and Risk Perceptions Motivating Illegal Migration Abroad: Port Harcourt City Youths, Nigeria. African Human Mobility Review 7: 49–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isokon, Brown Egbe, Esther Patrick Archibong, Oru Takim Tiku, and Egbe Ebagu Tangban. 2022. Negative attitude of youth towards African traditional values and socio-economic implications for Nigeria. Global Journal of Social Sciences 21: 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, Tanya, Danika Deibert, Graeme Wyatt, Quentin Durand-Moreau, Anil Adisesh, Kamlesh Khunti, Sachin Khunti, Simon Smith, Xin Hui S. Chan, Lawrence Ross, and et al. 2020. Classification of aerosol-generating procedures: A rapid systematic review. BMJ Open Respiratory Research 7: e000730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, Michael E., and Charles G. Hawley. 2007. Safety and survival at sea. Wilderness Medicine 83: 1780–82. [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger, Herbert. 2007. Echo state network. Scholarpedia 2: 2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jike, V. Teddy. 2004. Environmental degradation, social disequilibrium, and the dilemma of sustainable development in the Niger-Delta of Nigeria. Journal of Black Studies 34: 686–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalter, Christoph. 2024. Building Nations After Empire: Post-Imperial Migrations to Portugal in a Western European Context. Contemporary European History 33: 137–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kefale, Asnake, and Fana Gebresenbet, eds. 2021. Youth on the Move: Views from Below on Ethiopian International Migration. Oxford, UK: University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kiriscioglu, Eda, and Aysen Ustubici. 2025. “At Least, at the Border, I Am Killing Myself by My Own Will”: Migration Aspirations and Risk Perceptions among Syrian and Afghan Communities. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 23: 292–306. [Google Scholar]

- Korsi, Lawrence. 2022. Do we go or do we stay? Drivers of migration from the Global South to the Global North. African Journal of Development Studies 12: 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuschminder, Katie, Julia De Bresser, and Melissa Siegel. 2015. Irregular migration routes to Europe and factors influencing migrants’ destination choices. Maastricht: Maastricht Graduate School of Governance 1: 8–20. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmud, Hasan. 2023. International migration in Bangladesh: A political economic overview. In Migration in South Asia: IMISCOE Regional Reader. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 49–65. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, Douglas S. 2019. Economic development and international migration in comparative perspective. In Determinants of Emigration from Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean. London: Routledge, pp. 13–47. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, Robert. 2015. Who are we now? Astronomy & Geophysics 56: 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, Joseph A. 2021. Why qualitative methods are necessary for generalization. Qualitative Psychology 8: 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElroy, Gail. 2006. Committee representation in the European Parliament. European Union Politics 7: 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercieca, Duncan P., and Daniela Mercieca. 2022. Thinking through the death of migrants crossing the Mediterranean Sea: Mourning and grief as relational and as sites for resistance. Journal of Global Ethics 18: 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minaye, Abebaw, and Waganesh A. Zeleke. 2017. Attitude, risk perception and readiness of Ethiopian potential migrants and returnees towards unsafe migration. African Human Mobility Review 3: 702–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morehouse, Christal, and Michael Blomfield. 2011. Irregular Migration in Europe. Washington, DC: MPI. [Google Scholar]

- Mseleku, Zethembe. 2021. Youth high unemployment/unemployability in South Africa: The unemployed graduates’ perspectives. Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning 12: 775–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics. 2024. Nigeria Labour Force Survey Q1. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://www.nigerianstat.gov.ng/pdfuploads/NLFS_Q1_2024_Report.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwi94sfh6POAxXeYEEAHYMJDIwQFnoECBgQAw&usg=AOvVaw1f7-j3i9xsjoqjqhIYBnJC (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Okunade, Samuel Kehinde. 2021. Irregular emigration of Nigeria youths: An exploration of core drivers from the perspective and experiences of returnee migrants. In Intra-Africa Migrations. London: Routledge, pp. 50–69. [Google Scholar]

- Okunade, Samuel Kehinde, and Oladotun E. Awosusi. 2023. The Japa Syndrome and the Migration of Nigerians to the United Kingdom: An Empirical Analysis. Comparative Migration Studies 11: 27. [Google Scholar]

- Papademetriou, Demetrios. 2005. Managing unauthorised migration. Around the Globe 2: 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Pécoud, Antoine. 2018. What do we know about the International Organization for Migration? Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44: 1621–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platform for International Cooperation on Undocumented Migrants (PICUM). 2015. Council of Europe—Guaranteeing Access to Rights for All Children in the Context of Migration in Europe: A Matter of Human Rights. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/1680631cb0 (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Rippl, Susanne. 2002. Cultural theory and risk perception: A proposal for a better measurement. Journal of Risk Research 5: 147–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, Jane, and Liz Spencer. 2002. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In Analyzing Qualitative Data. London: Routledge, pp. 173–94. [Google Scholar]

- Templier, Mathieu, and Guy Paré. 2015. A framework for guiding and evaluating literature reviews. Communications of the Association for Information Systems 37: 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, Jacob, and Christel Oomen. 2015. Before the Boat: Understanding the Migrant Journey: EU Asylum: Towards 2020 Project. Brussels: Migration Policy Institute Europe. [Google Scholar]

- UNHCR. 2019a. Routes towards the mediterranean. Available online: https://data.unhcr.org/fr/documents/download/70090 (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- UNHCR. 2019b. UNHCR Global trends report: Forced displacement in 2018. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/sites/default/files/legacy-pdf/5d08d7ee7.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Vorvornator, Lawrence. 2025. “Ogya” Syndrome: Exploring Causes and Effects of Ghanaians International Migration. Journal of African Foreign Affairs 12: 111. [Google Scholar]

- Vorvornator, Lawrence Korsi. 2024a. Exploring South Africa’s Pre and Post-apartheid Border System: Border Securitisation, Illegal Migration and Cross-border Crimes. Journal of African Foreign Affairs 11: 123. [Google Scholar]

- Vorvornator, Lawrence Korsi. 2024b. Examining Migration Leverage and Coercion between Sending and Host Countries and their Success and Failure: The Global Perspective. African Renaissance (1744–2532) 21: 381–98. [Google Scholar]

- Vorvornator, Lawrence Korsi, and Joyce Mnesi Mdiniso. 2022. Drivers of corruption and its impact on Africa development: Critical reflections from a post-independence perspective. African Journal of Development Studies 2022: 295. [Google Scholar]

- Wildavsky, Aaron, and Karl Dake. 2018. Theories of risk perception: Who fears what and why? In The Institutional Dynamics of Culture, Volumes I and II. London: Routledge, pp. 243–62. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Allan M., and Vladimír Baláž. 2014. Migration, Risk and Uncertainty. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. 2023. Annual Report 2023. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/entities/publication/4683db9c-31bb-4bb0-9e00-ed6dc6aeae86 (accessed on 7 August 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vorvornator, L. Exploring Economic and Risk Perceptions Sparking Off-Shore Irregular Migration: West African Youth on the Move. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 560. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14090560

Vorvornator L. Exploring Economic and Risk Perceptions Sparking Off-Shore Irregular Migration: West African Youth on the Move. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(9):560. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14090560

Chicago/Turabian StyleVorvornator, Lawrence. 2025. "Exploring Economic and Risk Perceptions Sparking Off-Shore Irregular Migration: West African Youth on the Move" Social Sciences 14, no. 9: 560. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14090560

APA StyleVorvornator, L. (2025). Exploring Economic and Risk Perceptions Sparking Off-Shore Irregular Migration: West African Youth on the Move. Social Sciences, 14(9), 560. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14090560