The Impact of Cyberbullying Victimization on Adolescents’ School-Related Distress Across Nine Countries: Examining the Mitigating Role of Teacher Support

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Peer Victimization

1.2. Cyberbullying Victimization

1.3. School-Related Distress and Peer Victimization

1.4. Teacher Support

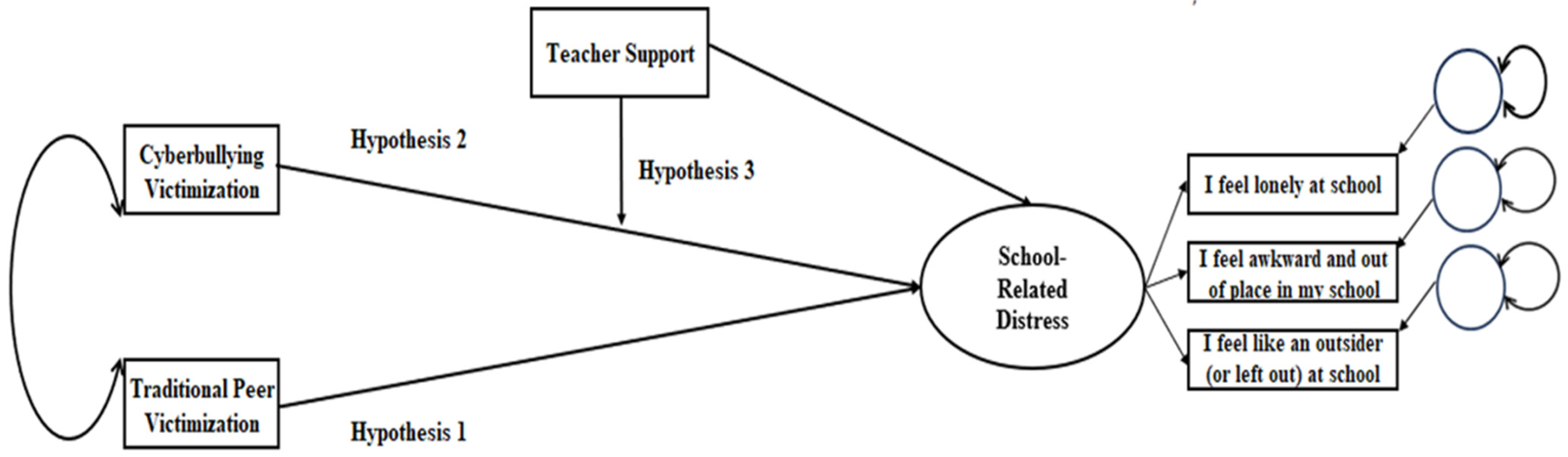

1.5. The Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. School-Related Distress

2.2.2. Peer Victimization

2.2.3. Cyberbullying Victimization

2.2.4. Teacher Support

2.2.5. Approach to Data Analysis

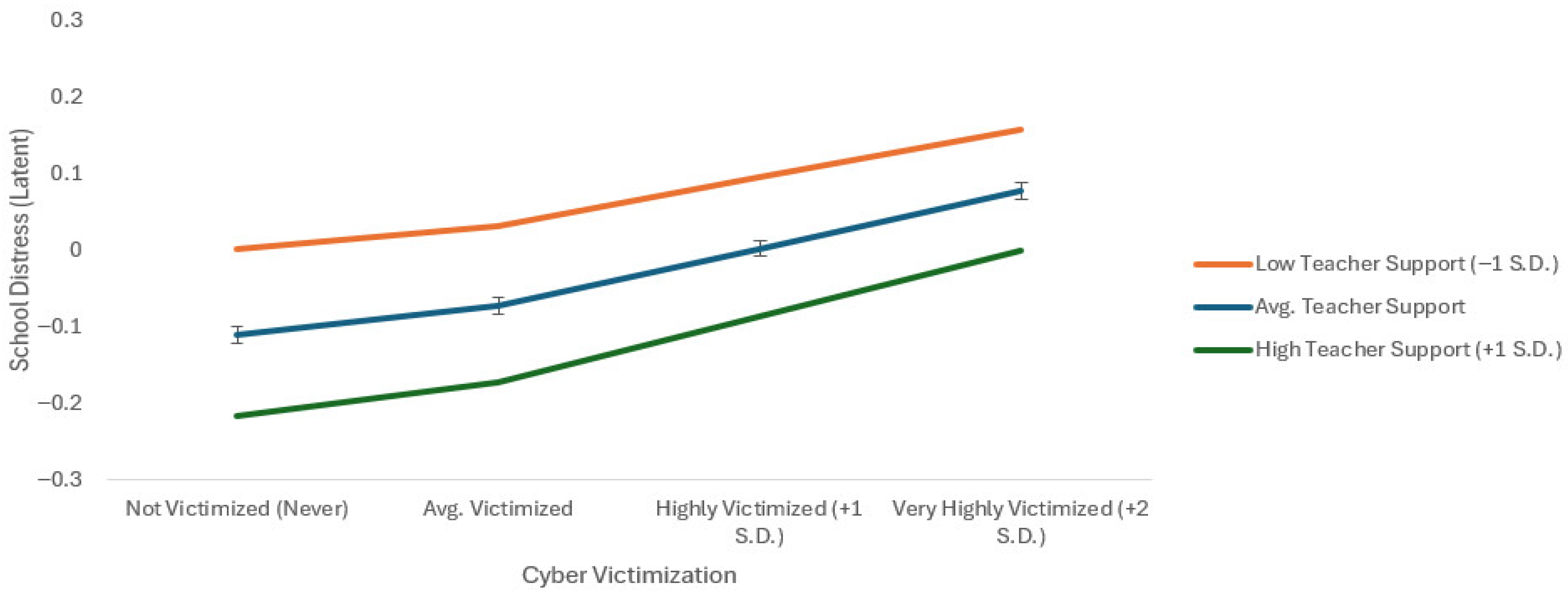

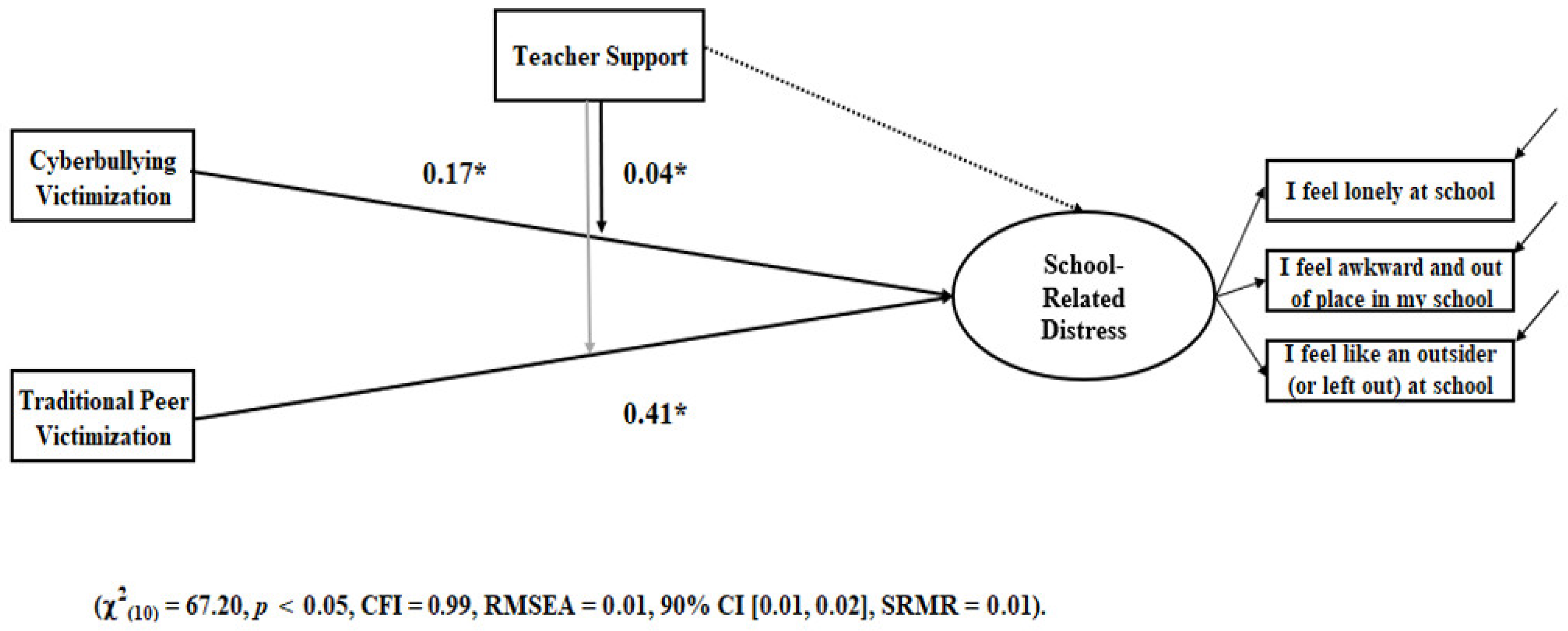

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Implications

4.2. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aboagye, Richard Gyan, Abdul-Aziz Seidu, John Elvis Hagan, James Boadu Frimpong, Eugene Budu, Collins Adu, Raymond K. Ayilu, and Bright Opoku Ahinkorah. 2021. A multi-country analysis of the prevalence and factors associated with bullying victimisation among in-school adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from the global school-based health survey. BMC Psychiatry 21: 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abo-Zena, Mona M., Keith Jones, and Jacqueline Mattis. 2022. Dismantling the master’s house: Decolonizing “rigor” in psychological scholarship. Journal of Social Issues 78: 298–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aceves, Mario J., Stephen P. Hinshaw, Rodolfo Mendoza-Denton, and Elizabeth Page-Gould. 2010. Seek help from teachers or fight back? Student perceptions of teachers’ actions during conflicts and responses to peer victimization. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 39: 658–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Aoyama, Ikuko, Terrill F. Saxon, and Danielle D. Fearon. 2011. Internalizing problems among cyberbullying victims and moderator effects of friendship quality. Multicultural Education & Technology Journal 5: 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, Jeffrey J. 2008. The neglected 95%: Why American psychology needs to become less American. American Psychologist 63: 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Axt, Jordan, Nicholas Buttrick, and Ruo Ying Feng. 2024. A comparative investigation of the predictive validity of four indirect measures of bias and prejudice. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 50: 871–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benvenuti, Martina, Michelle Wright, John Naslund, and Anne C. Miers. 2023. How technology use is changing adolescents’ behaviors and their social, physical, and cognitive development. Current Psychology 42: 16466–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, Tuhin, James G. Scott, Kerim Munir, Hannah J. Thomas, M. Mamun Huda, Mehedi Hasan, Tim David de Vries, Janeen Baxter, and Abdullah A. Mamun. 2020. Global variation in the prevalence of bullying victimisation amongst adolescents: Role of peer and parental supports. EClinicalMedicine 20: 100276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulton, Michael J., and Peter K. Smith. 1994. Bully/victim problems in middle-school children: Stability, self-perceived competence, peer perceptions and peer acceptance. British Journal of Developmental Psychology 12: 315–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branson, Christopher E., and Dewey G. Cornell. 2009. A comparison of self and peer reports in the assessment of middle school bullying. Journal of Applied School Psychology 25: 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, Urie. 1977. Toward an experimental ecology of human Development. American Psychologist 32: 513–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, Urie. 1979. The Ecology of Human Development. Harvard: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Mengdi, Marjolein Zee, Helma M. Y. Koomen, and Debora L. Roorda. 2019. Understanding cross-cultural differences in affective teacher-student relationships: A comparison between Dutch and Chinese primary school teachers and students. Journal of School Psychology 76: 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, Sheldon, and Thomas A. Wills. 1985. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin 98: 310–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colarossi, Lisa G., and Jacquelynne S. Eccles. 2003. Differential effects of support providers on adolescents’ mental health. Social Work Research 27: 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, David A., Rachel L. Zelkowitz, Elizabeth Nick, Nina C. Martin, Kathryn M. Roeder, Keneisha Sinclair-McBride, and Tawny Spinelli. 2016. Longitudinal and incremental relation of cybervictimization to negative self-cognitions and depressive symptoms in young adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 44: 1321–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, Sophie E., Hannah Constable, and Sinéad L. Mullally. 2022. School distress in UK school children: A story dominated by neurodivergence and unmet needs. medRxiv, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornell, Dewey G., and Karen Brockenbrough. 2013. Identification of bullies and victims: A comparison of methods. In Issues in School Violence Research. London: Routledge, pp. 63–87. [Google Scholar]

- Correia, Isabel, and Claudia Dalbert. 2007. Belief in a just world, justice concerns, and well-being at Portuguese schools. European Journal of Psychology of Education 22: 421–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielsen, Anne G., Nora Wiium, Britt U. Wilhelmsen, and Bente Wold. 2010. Perceived support provided by teachers and classmates and students’ self-reported academic initiative. Journal of School Psychology 48: 247–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demaray, Michelle Kilpatrick, and Christine Kerres Malecki. 2003. Perceptions of the frequency and importance of social support by students classified as victims, bullies, and bully/victims in an urban middle school. School Psychology Review 32: 471–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, J. K., and R. Veenstra. 2011. Peer relations. Encyclopedia of Adolescence 2: 255–59. [Google Scholar]

- Dooley, Julian J., Jacek Pyżalski, and Donna Cross. 2009. Cyberbullying versus face-to-face bullying: A theoretical and conceptual review. Zeitschrift für Psychologie/Journal of Psychology 217: 182–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauman, Michael A. 2008. Cyber bullying: Bullying in the digital age. American Journal of Psychiatry 165: 780–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Yi, and Gregory R. Hancock. 2022. Model-based incremental validity. Psychological Methods 27: 1039–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flaspohler, Paul D., Jennifer L. Elfstrom, Karin L. Vanderzee, Holli E. Sink, and Zachary Birchmeier. 2009. Stand by me: The effects of peer and teacher support in mitigating the impact of bullying on quality of life. Psychology in the Schools 46: 636–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardella, Joseph H., Benjamin W. Fisher, and Abbie R. Teurbe-Tolon. 2017. A systematic review and meta-analysis of cyber-victimization and educational outcomes for adolescents. Review of Educational Research 87: 283–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gini, Gianluca, Claudia Marino, Tiziana Pozzoli, and Melissa Holt. 2018. Associations between peer victimization, perceived teacher unfairness, and adolescents’ adjustment and well-being. Journal of School Psychology 67: 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heerde, Jessica A., and Sheryl A. Hemphill. 2018. Examination of associations between informal help-seeking behavior, social support, and adolescent psychosocial outcomes: A meta-analysis. Developmental Review 47: 44–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellfeldt, Karin, Laura López-Romero, and Henrik Andershed. 2020. Cyberbullying and psychological well-being in young adolescence: The potential protective mediation effects of social support from family, friends, and teachers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17: 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, James S. 1983. Work Stress and Social Support. Boston: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Li-Tze, and Peter M. Bentler. 1999. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 6: 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Chaoxin, and Jiaming Shi. 2024. The relationship between bullying victimization and problematic behaviors: A focus on the intrapersonal emotional competence and interpersonal social competence. Child Abuse & Neglect 152: 106800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judd, Charles M., Vincent Y. Yzerbyt, and Dominique Muller. 2014. Mediation and moderation. Handbook of Research Methods in Social and Personality Psychology 2: 653–76. [Google Scholar]

- Juvonen, Jaana, and Elisheva F. Gross. 2008. Extending the school grounds?—Bullying experiences in cyberspace. Journal of School Health 78: 496–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juvonen, Jaana, and Sandra Graham, eds. 2001. Peer Harassment in School: The Plight of the Vulnerable and Victimized. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Keefe, Susan, Amado Padilla, and Manuel Carlos. 1979. The Mexican-American extended family as an emotional support system. Human Organization 38: 144–52. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/44126072 (accessed on 14 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Kim, Samuel Seunghan, Wendy Marion Craig, Nathan King, Ludwig Bilz, Alina Cosma, Michal Molcho, Gentiana Qirjako, Margarida Gaspar De Matos, Lilly Augustine, Kastytis Šmigelskas, and et al. 2022. Bullying, mental health, and the moderating role of supportive adults: A cross-national analysis of adolescents in 45 countries. International Journal of Public Health 67: e1604264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kline, Rex. 2005. Principles & Practice of Structural Equation Modelling. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kljakovic, Moja, and Caroline Hunt. 2016. A meta-analysis of predictors of bullying and victimisation in adolescence. Journal of Adolescence 49: 134–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kochenderfer-Ladd, Becky, and Gary W. Ladd. 2010. A child-by-environment framework for planning interventions with children involved in bullying. In Preventing and Treating Bullying and Victimization. Edited by Eric M. Vernberg and Bridget K. Biggs. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 45–74. [Google Scholar]

- Koyanagi, Ai, Hans Oh, Andre F. Carvalho, Lee Smith, Josep Maria Haro, Davy Vancampfort, Brendon Stubbs, and Jordan E. DeVylder. 2019. Bullying victimization and suicide attempt among adolescents aged 12–15 years from 48 countries. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 58: 907–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, Irene, Kelly Dickson, Michelle Richardson, Wendy MacDowall, Helen Burchett, Claire Stansfield, Ginny Brunton, Katy Sutcliffe, and James Thomas. 2020. Cyberbullying and children and young people’s mental health: A systematic map of systematic reviews. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 23: 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Shanyan, Claudio Longobardi, Sofia Mastrokoukou, and Matteo Angelo Fabris. 2025. Bullying victimization and psychological adjustment in Chinese students: The mediating role of teacher–student relationships. School Psychology International 46: 68–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, Cristy, and David L. DuBois. 2005. Peer victimization and rejection: Investigation of an integrative model of effects on emotional, behavioral, and academic adjustment in early adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology 34: 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeely, Clea, and Christina Falci. 2004. School connectedness and the transition into and out of health-risk behavior among adolescents: A comparison of social belonging and teacher support. The Journal of school health 74: 284–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modecki, Kathryn L., Jeannie Minchin, Allen G. Harbaugh, Nancy G. Guerra, and Kevin C. Runions. 2014. Bullying prevalence across contexts: A meta-analysis measuring cyber and traditional bullying. Journal of Adolescent Health 55: 602–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, Sophie, Rosana E. Norman, Shuichi Suetani, Hannah J. Thomas, Peter D. Sly, and James G. Scott. 2017. Consequences of bullying victimization in childhood and adolescence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World Journal of Psychiatry 7: 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdock, Tamera B. 1999. The social context of risk: Status and motivational predictors of alienation in middle school. Journal of Educational Psychology 91: 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, Linda K., and Bengt O. Muthén. 2015. Mplus User’s Guide (7.2). Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Nagar, Pooja Megha, and Victoria Talwar. 2023. The role of teacher support in increasing youths’ intentions to disclose cyberbullying experiences to teachers. Computers & Education 207: 104922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamoto, Jonathan, and David Schwartz. 2010. Is peer victimization associated with academic achievement? A meta-analytic review. Social Development 19: 221–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nansel, Tonja R., Mary Overpeck, Ramani S. Pilla, W. June Ruan, Bruce Simons-Morton, and Peter Scheidt. 2001. Bullying behaviors among US youth: Prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. JAMA 285: 2094–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, Gayle, Cindy Lutenbacher, and María Elena López. 2001. A Cross-cultural Study of Mexico and the United States: Perceived Roles of Teachers. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 22: 463–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nixon, Charisse. 2014. Current perspectives: The impact of cyberbullying on adolescent health. Adolescent Health, Medicine and Therapeutics 5: 143–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2021. Beyond Academic Learning: First Results from the Survey of Social and Emotional Skills. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olweus, D. 1993. Bullying at School: What We Know and What We Can Do. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Patchin, Justin W., and Sameer Hinduja. 2006. Bullies move beyond the schoolyard: A preliminary look at cyberbullying. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice 4: 148–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pate, Christina M., Melissa A. Maras, Stephen D. Whitney, and Catherine P. Bradshaw. 2017. Exploring psychosocial mechanisms and interactions: Links between adolescent emotional distress, school connectedness, and educational achievement. School Mental Health 9: 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, Anthony D. 1998. Bullies and victims in school: A review and call for research. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 19: 165–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, Anthony D., Maria Bartini, and Fred Brooks. 1999. School bullies, victims, and aggressive victims: Factors relating to group affiliation and victimization in early adolescence. Journal of Educational Psychology 91: 216–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepler, Debra, Wendy M. Craig, and Paul O’Connell. 1999. Understanding bullying from a dynamic systems perspective. In The Blackwell Reader in Development Psychology. Edited by Alan Slater and Darwin Muir. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, pp. 440–51. [Google Scholar]

- Perren, Sonja, and Françoise D. Alsaker. 2006. Social behavior and peer relationships of victims, bully-victims, and bullies in kindergarten. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 47: 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perren, Sonja, Julian Dooley, Thérèse Shaw, and Donna Cross. 2010. Bullying in school and cyberspace: Associations with depressive symptoms in Swiss and Australian adolescents. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health 4: 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, David G., Sara J. Kusel, and Louise C. Perry. 1988. Victims of peer aggression. Developmental psychology 24: 807–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. 2023. Teens, Social Media and Technology 2023. Available online: https://abfe.issuelab.org/resources/43096/43096.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Podsakoff, Philip M., Scott B. MacKenzie, and Nathan P. Podsakoff. 2012. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology 63: 539–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reijntjes, Albert, Jan H. Kamphuis, Peter Prinzie, and Michael J. Telch. 2010. Peer victimization and internalizing problems in children: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Child Abuse & Neglect 34: 244–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigby, Ken. 2001. Health consequences of bullying and its prevention in schools. In Peer Harassment in School: The Plight of the Vulnerable and Victimized. Edited by Jaana Juvonen and Sandra Graham. New York: Guilford Press, pp. 315–31. [Google Scholar]

- Rigby, Ken, and Dale Bagshaw. 2003. Prospects of adolescent students collaborating with teachers in addressing issues of bullying and conflict in schools. Educational Psychology 23: 535–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sameroff, Arnold J. 2000. Developmental systems and psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology 12: 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santo, Jonathan B., Alexa Martin-Storey, Holly Recchia, and William M. Bukowski. 2018. Self-continuity moderates the association between peer victimization and depressed affect. Journal of Research on Adolescence 28: 875–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, David, Jennifer E. Lansford, Kenneth A. Dodge, Gregory S. Pettit, and John E. Bates. 2015. Peer victimization during middle childhood as a lead indicator of internalizing problems and diagnostic outcomes in late adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology 44: 393–404. [Google Scholar]

- Sechrest, Lee. 1963. Incremental validity: A recommendation. Educational and Psychological Measurement 23: 153–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shear, Benjamin R., and Bruno D. Zumbo. 2013. False positives in multiple regression: Unanticipated consequences of measurement error in the predictor variables. Educational and Psychological Measurement 73: 733–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slonje, Robert, Peter K. Smith, and Ann Frisén. 2013. The nature of cyberbullying, and strategies for prevention. Computers in Human Behavior 29: 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Lee, Guillermo F. López Sánchez, Josep Maria Haro, Abdullah Ahmed Alghamdi, Damiano Pizzol, Mark A. Tully, Hans Oh, Poppy Gibson, Helen Keyes, Laurie Butler, and et al. 2023. Temporal trends in bullying victimization among adolescents aged 12–15 years from 29 countries: A global perspective. Journal of Adolescent Health 73: 582–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, Peter K., and Robert Slonje. 2009. Cyberbullying: The nature and extent of a new kind of bullying, in and out of school. In Handbook of Bullying in Schools. London: Routledge, pp. 249–61. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Peter K., Jess Mahdavi, Manuel Carvalho, Sonja Fisher, Shanette Russell, and Neil Tippett. 2008. Cyberbullying: Its nature and impact in secondary school pupils. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 49: 376–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorrentino, Anna, Francesco Sulla, Margherita Santamato, Marco di Furia, Giusi Antonia Toto, and Lucia Monacis. 2023. Has the COVID-19 pandemic affected cyberbullying and cybervictimization prevalence among children and adolescents? A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20: 5825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardy, Charles H. 1985. Social support measurement. American Journal of Community Psychology 13: 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thalmayer, Amber Gayle, Cecilia Toscanelli, and Jeffrey Jensen Arnett. 2021. The neglected 95% revisited: Is American psychology becoming less American? American Psychologist 76: 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoits, Peggy A. 1986. Social support as coping assistance. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 54: 416–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokunaga, Robert S. 2010. Following you home from school: A critical review and synthesis of research on cyberbullying victimization. Computers in Human Behavior 26: 277–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troop-Gordon, Wendy. 2017. Peer victimization in adolescence: The nature, progression, and consequences of being bullied within a developmental context. Journal of Adolescence 55: 116–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Geel, Mitch, Anouk Goemans, Wendy Zwaanswijk, Gianluca Gini, and Paul Vedder. 2018. Does peer victimization predict low self-esteem, or does low self-esteem predict peer victimization? Meta-analyses on longitudinal studies. Developmental Review 49: 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Claudia, Yin Li, Kaigang Li, and Dong-Chul Seo. 2018. Body weight and bullying victimization among US adolescents. American Journal of Health Behavior 42: 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westfall, Jacob, and Tal Yarkoni. 2016. Statistically controlling for confounding constructs is harder than you think. PLoS ONE 11: e0152719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, Katrina, Mike Chambers, Stuart Logan, and Derek Robinson. 1996. Association of common health symptoms with bullying in primary school children. BMJ 313: 17–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolke, Dieter, Sarah Woods, Linda Bloomfield, and Lyn Karstadt. 2000. The association between direct and relational bullying and behaviour problems among primary school children. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines 41: 989–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Lili, Dajun Zhang, Zhiqiang Su, and Tianqiang Hu. 2015. Peer victimization among children and adolescents: A meta-analytic review of links to emotional maladjustment. Clinical Pediatrics 54: 941–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Joo Young, Kristina L. McDonald, and Sunmi Seo. 2022. Attributions about peer victimization in US and Korean adolescents and associations with internalizing problems. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 51: 2018–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ybarra, Michele L., Kimberly J. Mitchell, Janis Wolak, and David Finkelhor. 2006. Examining characteristics and associated distress related to internet harassment: Findings from the second youth internet safety survey. Pediatrics 118: e1169-77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Huimei, Tiantian Han, Shaodi Ma, Guangbo Qu, Tianming Zhao, Xiuxiu Ding, Liang Sun, Qirong Qin, Mingchun Chen, Yehuan Sun, and et al. 2022. Association of child maltreatment and bullying victimization among Chinese adolescents: The mediating role of family function, resilience, and anxiety. Journal of Affective Disorders 299: 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Wei, Feiyun Ouyang, Oyun-Erdene Nergui, Joseph Benjamin Bangura, Kwabena Acheampong, Isaac Yaw Massey, and Shuiyuan Xiao. 2020. Child and adolescent mental health policy in low-and middle-income countries: Challenges and lessons for policy development and implementation. Frontiers in Psychiatry 11: 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Chengyan, Shiqing Huang, Richard Evans, and Wei Zhang. 2021. Cyberbullying among adolescents and children: A comprehensive review of the global situation, risk factors, and preventive measures. Frontiers in Public Health 9: 634–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country | Girls | Boys | Total | Mage | SDage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | 1020 | 1019 | 2039 | 15.40 | 0.60 |

| USA | 1542 | 1346 | 2888 | 15.41 | 0.51 |

| Colombia | 3447 | 3302 | 6749 | 15.40 | 0.62 |

| Finland | 1249 | 1083 | 2332 | 15.30 | 0.50 |

| Russia | 1659 | 1716 | 3375 | 15.49 | 0.52 |

| Turkey | 1818 | 1287 | 3105 | 15.45 | 0.50 |

| South Korea | 1667 | 1579 | 3246 | 15.70 | 0.45 |

| Portugal | 831 | 746 | 1577 | 15.50 | 0.52 |

| China | 1745 | 1827 | 3572 | 15.30 | 0.50 |

| Total | 14,978 | 13,905 | 28,883 | 15.43 | 0.52 |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. I feel like an outsider (or left out) at school | - | |||||||

| 2. I feel awkward and out of place in my school | 0.50 ** | - | ||||||

| 3. I feel lonely at school | 0.56 ** | 0.51 ** | - | |||||

| 4. Traditional peer victimization | 0.30 ** | 0.27 ** | 0.32 ** | - | ||||

| 5. Cyberbullying victimization | 0.19 ** | 0.16 ** | 0.18 ** | 0.42 ** | - | |||

| 6. Teacher support | −0.16 ** | −0.19 ** | −0.18 ** | −0.13 ** | −0.13 ** | - | ||

| 7. Mean (M) | 1.75 | 1.85 | 1.73 | 1.39 | 1.22 | 3.26 | - | |

| 8. Standard Deviation (SD) | 0.79 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.58 | 0.43 | 0.77 | - |

| Variable | b | β | S.E. | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional peer victimization | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.01 | <0.001 |

| Cyberbullying victimization | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.01 | <0.001 |

| Teacher support | −0.14 | −0.18 | 0.01 | <0.001 |

| Interaction | 0.04 | 0.12 | 0.01 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McVay, S.S.; Santo, J.; Lydiatt, H. The Impact of Cyberbullying Victimization on Adolescents’ School-Related Distress Across Nine Countries: Examining the Mitigating Role of Teacher Support. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 559. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14090559

McVay SS, Santo J, Lydiatt H. The Impact of Cyberbullying Victimization on Adolescents’ School-Related Distress Across Nine Countries: Examining the Mitigating Role of Teacher Support. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(9):559. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14090559

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcVay, Shaghayegh Sheri, Jonathan Santo, and Hannah Lydiatt. 2025. "The Impact of Cyberbullying Victimization on Adolescents’ School-Related Distress Across Nine Countries: Examining the Mitigating Role of Teacher Support" Social Sciences 14, no. 9: 559. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14090559

APA StyleMcVay, S. S., Santo, J., & Lydiatt, H. (2025). The Impact of Cyberbullying Victimization on Adolescents’ School-Related Distress Across Nine Countries: Examining the Mitigating Role of Teacher Support. Social Sciences, 14(9), 559. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14090559