1. Introduction

This framework contains three interrelated concepts: capabilities, functionings and agency (

Robeyns 2011). While capabilities reveal a variety of possible combinations of functionings (doing and being) that a person can achieve, functionings refer to ‘made’ and are concretely realised by the person. “Capability is, thus, a set of vectors of functionings, reflecting the person’s freedom to lead one type of life or another” (

Sen 1992, p. 40). Capabilities are, therefore, a notion of positive freedom that refers to the real opportunities a person has with regard to the life they want to lead (

Sen 1987, p. 86). Capabilities are associated with agency, i.e., “the ability to pursue goals that one values and has reason to value” (

Comin et al. 2011, p. 7). It entails the ability to make choices and influence one’s environment. The concept of agency is particularly important for social work, which “emphasises that all individuals, regardless of age, are not passive recipients of social provisions but rather active agents who have choices about the shaping of their life trajectories” (

Schweiger 2025, p. 2). Conversion factors also play a decisive role in the capabilities approach, as personal (internal) factors and external (social, family, cultural, structural, etc.) factors that can facilitate or impede an individual’s ability to convert resources into concrete achievements (

Sen 1999,

2009).

This approach sheds much needed light on the study of poverty by considering this problem as a deprivation of capabilities and therefore of the freedom to lead a desired life. It facilitates a multidimensional analysis of this problem and the various obstacles faced by the individuals and communities concerned, which goes beyond a vision centred on material deficits, incorporating the notion of action and examining real freedoms, i.e., freedom for voice, thus opening up opportunities to choose, influence and aspire (

Appadurai 2004). In the analysis of poverty,

Appadurai (

2004) highlighted the need to strengthen the voices of the poor in order to understand not only their experiences of deprivation but also their collective aspirations. “(The) voice must be expressed in terms of actions and performances which have local cultural force” (

Appadurai 2004, p. 67). Therefore, he identifies social and community work as key conversion factors in building the capability to aspire of the poor (

Appadurai 2004, p. 73).

Applied to CYP, the capability approach recognises the devastating effect of poverty on children and young people in terms of their present (being) and future (becoming) development (

Ballet et al. 2011;

Biggeri et al. 2011;

Stoecklin 2018). It thus allows the multidimensional nature of child development and its aspirations (

C. S. Hart 2012) for considering and capturing the dynamic process of “evolving capabilities” specific to CYP (

Ballet et al. 2011). This process incorporates the opportunities that CYP have today and tomorrow, their capacities over time, and their agency as an evolving and age-related freedom. The level of agency of CYP depends not only on their age but also on the concrete opportunities for participation offered by their environment (communities, institutions, etc.), as conversion factors (positive or negative). Therefore, “(participation) is also central to the process and freedom of agency, and it is instrumental to the expansion of capabilities and facilitating the fulfilment of rights” (

Biggeri and Karkara 2014, p. 29).

Drawing on the capability approach, this article presents a specific definition of child poverty developed from an empirical study conducted in Switzerland between 2021 and 2025, which focused on the experiences of CYP. This subjective, multi-dimensional definition deserves special consideration both for measuring child poverty in this economically advanced country and for developing relevant intervention mechanisms. However, in Switzerland, child poverty, like poverty in other age groups, is defined mainly through the prism of preconceived measures centred on the monetary dimension. It is structured around two main conceptions of poverty—the absolute and the relative.

1 The former pertains to an individual’s basic needs, while the latter focuses on income distribution.

2 Informed by these two concepts, it has been concluded that poverty in Switzerland affects 702,000 people, including 90,000 children (0–17 years), and represents a poverty rate of 6.4% and an at-risk-of-poverty rate of 17.9% for this age group (

OFS 2023). The at-risk-of-poverty rate is actually higher for children than for adults of working age. Compared to other rich countries, the risk of child poverty in Switzerland has increased by 10% over the last ten years, representing a substantial surge (

UNICEF 2023).

Just like in other countries, the rate and risk of child poverty in Switzerland are established by means of quantitative surveys using households as the unit of analysis (e.g., SILC surveys) and gathering the views mainly of adults. This type of measurement assumes that a single person (an adult) within a household is capable of providing the relevant information for all its members. Therefore, the resultant data masks the differentiated impact of poverty on individuals and does not reveal intra-household inequalities and the specific experiences of CYP. This observation also applies to the latest tool for measuring and combating poverty: National Poverty Monitoring (

BSV 2023). This tool, anchored explicitly in Amartya Sen’s Capability Approach framework, aims to develop a multidimensional understanding of poverty, but still remains focused on adults and the monetary dimension of the problem.

3 Recent empirical work (

Bray et al. 2019, p. 7;

Bessell 2021), including our study in Switzerland (

Garcia Delahaye et al. 2024), demonstrates that the value of a multidimensional perspective on poverty, formulated in congruence with the Capability Approach, also lies in taking account of the dimensions recognised by those affected (

Alkire 2013, p. 3;

Alkire and Foster 2011), including the CYP concerned. This indicates that the current measures of poverty do not consider the experience of affected CYP, which ultimately leads to a complete oversight of what is important to them. This shortcoming makes it difficult to institute appropriate measures to ensure real improvement in the living conditions of this group and provide the support to enhance their capabilities (“from being to becoming”) (

Ballet et al. 2011), thereby stalling processes essential for their ‘well-being’ and ‘well-becoming’ (

Biggeri and Santi 2012).

In line with the International Convention on the Rights of the Child (Article 12 et seq.) and the three founding pillars of CYP policies in Switzerland—participation, protection and encouragement

4— the participation of CYP, including those from socially disadvantaged backgrounds, is recognised as a fundamental and unconditional right. In social work practice, ‘participation’ functions both as a core value underpinning social interventions (constitutive dimension) and as a guiding principle for action (instrumental dimension), intended to ensure the quality and efficiency of services and to strengthen the resilience of public and para-public institutions (

Garcia Delahaye and Libois 2021). Its operationalisation, however, remains a persistent challenge, particularly in conditional intervention fields such as social welfare (

Garcia Delahaye et al. 2024). As already mentioned, participation is central to the expansion of capabilities and the fulfilment of rights (

Biggeri and Karkara 2014, p. 29). The discussion section will be developed around the importance of CYP’s right to participation and its possible operationalisation as an innovative tool within social work institutions.

With this challenge in view, the article draws on our research to highlight the potential of the capability approach in transforming social work practices, particularly those focusing on reducing and/or eradicating child poverty. The guiding questions framing this study are mentioned below.

- -

What new avenues of knowledge production on the deprivations and aspirations of CYP experiencing poverty emerge when their voices are incorporated into the research process?

- -

What kinds of intervention in social work practice have been effective in promoting the meaningful participation of CYP with the goal of breaking the cycle of poverty as an intergenerational legacy?

- -

How can social work support the evolving capabilities of the socially disadvantaged CYP?

- -

What are the capabilities that need to be strengthened from the perspective of transformative social intervention, including its institutions and the supporting policy framework?

2. Materials and Methods

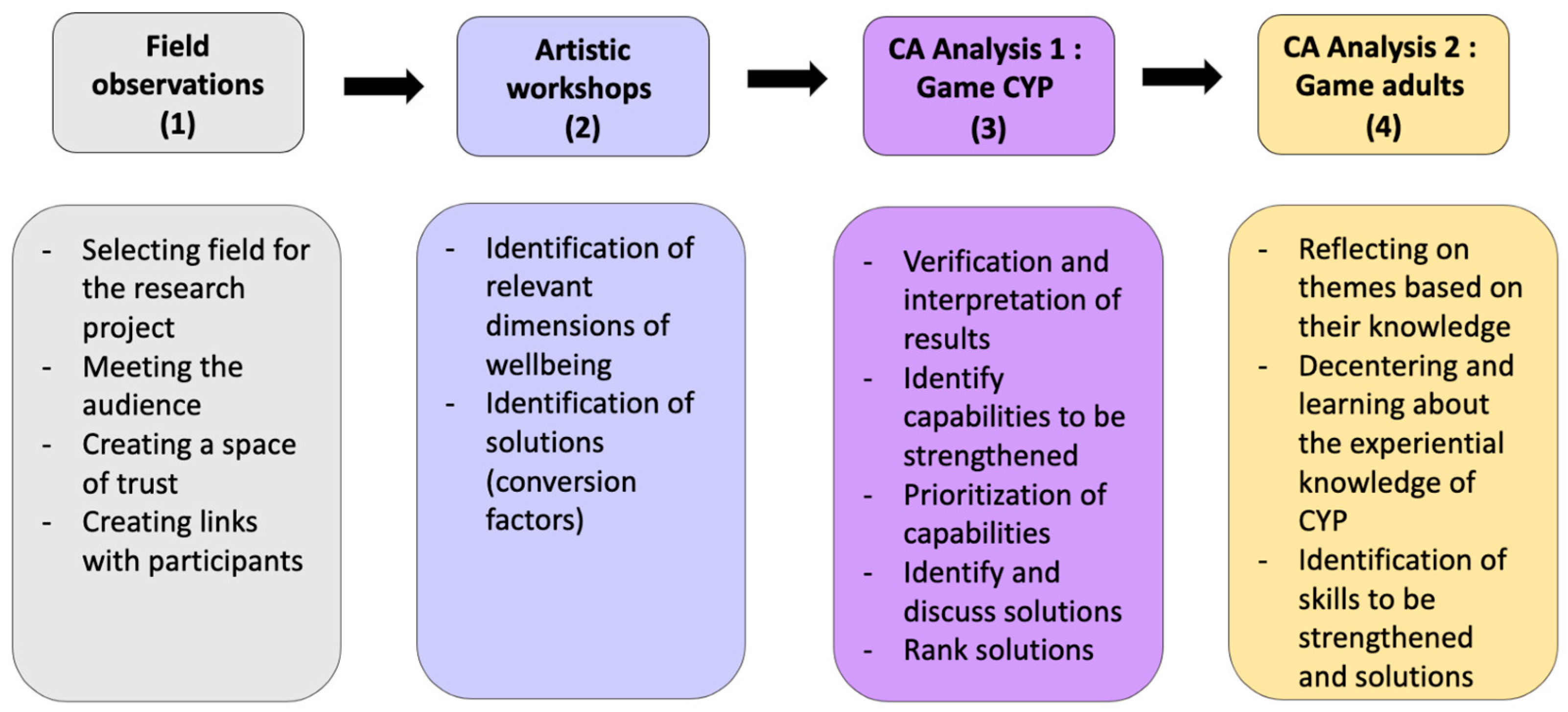

The two main aims of this research project are: (1) to (re)conceptualise child poverty on the basis of the experiences of CYP; and (2) to develop a methodological framework capable of supporting their voices, i.e., recognising experiential knowledge as indispensable to understanding the issues under study and to develop informed plans of action. The study has been structured around an evolving methodology developed across four phases (

Figure 1). This included field visits and observations, workshops on artistic creation and the production of images by CYP, joint analysis of the empirical material collected and participatory feedback.

The research team comprises researchers, artists and young co-researchers who share their own experiences while supporting their peers and other participants through a collaborative learning process during the study (

Garcia Delahaye et al. 2023a;

Schweiger 2024;

Larkins and Satchwell 2023)

5. This research, funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) and led by a university of applied sciences in social work, is supported by a team that also includes experts in community development, whose skills have been developed through diverse field experiences. This expertise forms an embodied professional knowledge, granting the research team a distinctive position. While framed within the objectives of action research, this position is accompanied by continuous ethical and reflexive attention on how knowledge is constructed and the power dynamics inherent in research. It enables the creation of strong connections with participants through extended immersion in leisure activities, while ensuring a respectful and co-constructed process. This approach goes beyond merely collecting the voices of CYP. It aims to amplify them as widely as possible through diverse and innovative dissemination strategies, ultimately contributing towards a more democratic circulation of knowledge.

The total sample included 350 CYP, aged between 4 and 25, aligning with the age groups defined in Swiss CYP policies. The participants are of 40 different nationalities, including Swiss, who reside in Switzerland, and live in couple-parent, single-parent or large families, which allows for both acknowledging and extending beyond the current state of knowledge on child poverty, with migration and family composition identified as risk factors. Their convergence was made possible through relationships established with associations and institutions dedicated to combating poverty, which, since the COVID-19 pandemic, have been providing weekly food distributions across four different cantons in both the French and German-speaking regions. These locations were also selected based on the indicators relating to social and spatial inequalities in Switzerland as well as the interest shown in the research approach by the people we engaged with (professionals, parents, CYP and co-researchers).

The core of this participatory and artistic methodology, titled My Voice in Images

6 (

Ma Voix en images), is inspired by art-based methods (

Garcia Delahaye et al. 2023a;

Loser 2023;

Wright 2019;

Nunn 2020;

Coemans et al. 2015;

Leavy 2018). It involves the creation of photographic or filmed images by CYP as a means of self-expression and advocacy for a more fulfilling life (

Aristotle 1992). Given that child poverty is a taboo subject in Switzerland (

Ostorero 2007), this methodology was designed to facilitate the expression of complex experiences and the emergence of experiential knowledge that is often difficult to articulate through ‘traditional’ research methods. It also ensures strict adherence to participant anonymity, respects image rights, and guarantees informed consent.

The stages of the methodology presented in

Figure 1 are part of a cyclical, organic and iterative process, based on the collaboration of the research team—co-researchers, researchers, and artists—at every stage (for example, selection of data collection tools used, co-analysis of the produced images, etc.). A game for the general public, co-created with young co-researchers to support discussions around the images and the narratives produced, served both to validate the analyses conducted and to facilitate the collective search for solutions—understood as ‘conversion factors’ (

Sen 1999,

2009)—for the identified problem. The conversion factors relevant for CYP operate at four different levels: 1. individual level (age, sex, talent, etc.), 2. family level (income, shelter, food, etc.), 3. community level (social capital, traditional norms, solidarity, etc.), and 4. regional or national levels (public goods investment, legal framework) (

Trani et al. 2011, p. 253). Moreover, the game also facilitated the establishment and discussion of a list of capabilities identified by CYP during the research. Indeed, the research adopts the capability approach as envisioned by Sen, involving a democratic process to identify the capabilities that are relevant within a given society and context.

The game session concluded with a collective discussion around capabilities—referred to as “superpowers” (

Figure 2) for the purpose of the activity. Starting from a guiding question that invited participants to identify and prioritise their capabilities, they engaged in debate and constructed reasoned arguments about their relative importance. The aim was also to highlight the necessary conversion factors to strengthen the capabilities from the perspective of CYP affected by poverty.

Each stage of data collection, creative workshops and play sessions was recorded and then transcribed in order to carry out a structured qualitative content analysis (

Mayring 2015) by coding the most significant themes. The coding was carried out by the research team in a broad, inductive manner. A co-analysis workshop with the co-researchers was then conducted to test the preliminary findings and deepen their interpretation. Through this stage, the co-researchers interpreted the codes by grouping them into major categories, leading to the five dimensions of child poverty described below. These themes were subsequently

7. The socio-demographic characteristics of the participants (age, gender, nationality, area of residence, etc.) were also considered when analysing the research results. This approach enabled the locally emerging trends to be contextualised and generalised at the national level through comparative analysis between the cantons. These trends were then examined with reference to the views of the young co-researchers and participants, to promote the emergence of new directions, fostering new insights and putting the research results to the test. This work was extended further through games with the adults (

Figure 3), with the aim of amplifying and presenting the research findings to experts, particularly in the field of social welfare, and above all to influence the social systems on the basis of the experiences of deprivation and the aspirations of CYP.

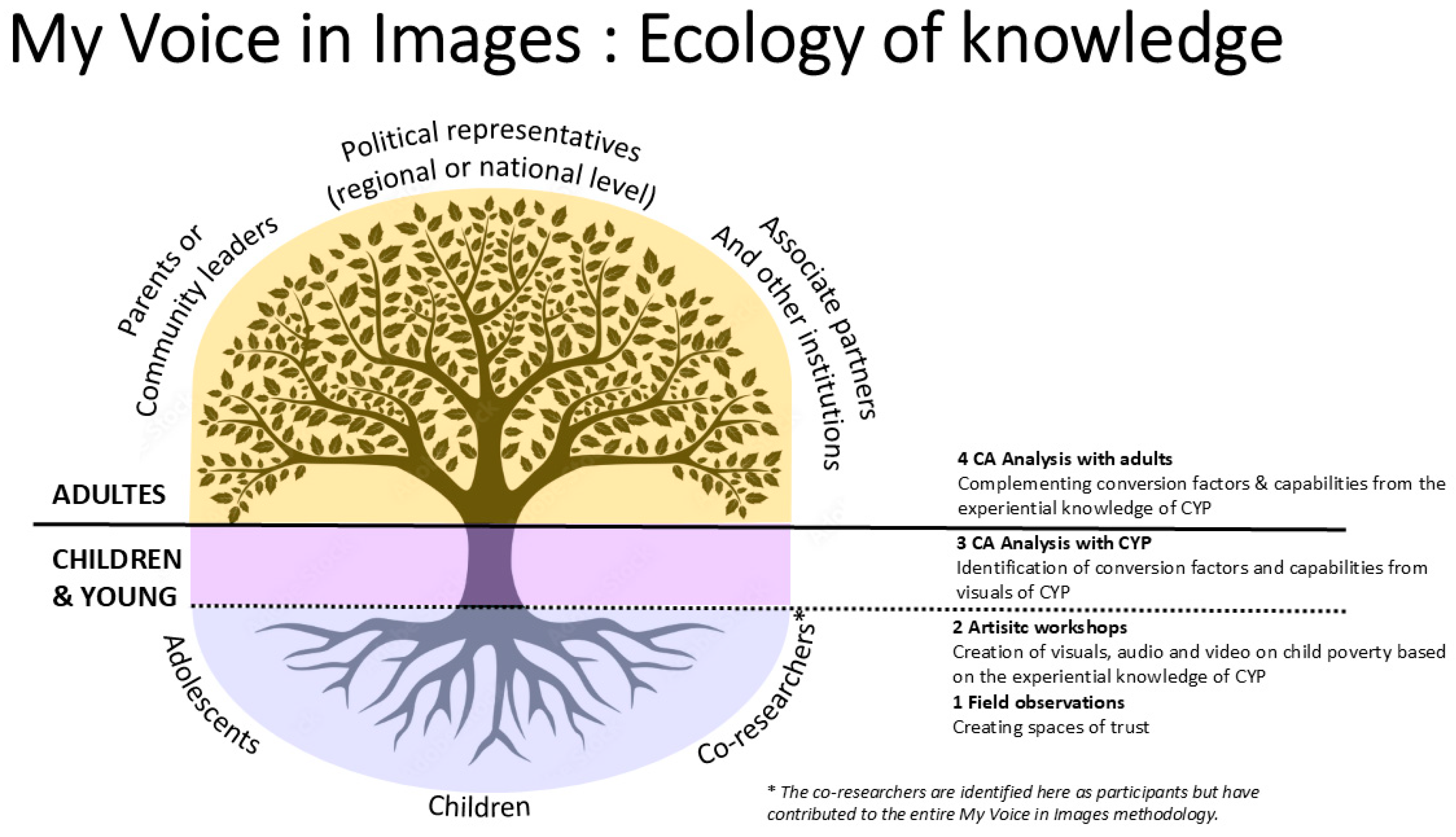

As shown in the

Figure 4 (which represents only a static snapshot of what is, in fact, a dynamic process), the knowledge emerging from the research, particularly the definition of child poverty, is rooted in the foundations of the tree, embodied in the experiential knowledge of CYP. This knowledge lies at the heart of the democratic debate initiated through the game, which goes beyond simply creating a list of CYP capabilities. It highlights the conversion factors (solutions) that need to be strengthened in order to eradicate child poverty.

Grounded in Sen’s conceptualisation of the capability approach and its emphasis on democratic processes, the research focused on developing a methodology that would enable the operationalisation of this approach in practice. Furthermore, this article adopts a social work perspective, seeking to identify the capabilities that are constrained and those that need to be reinforced within social institutions. Although difficult to implement, the capability approach combined with participatory and inclusive methodologies (

Martinez-Vargas et al. 2021) makes it possible to reintroduce and revalue the voice of CYP as an epistemic, ethical and political lever. The focus is no longer simply on studying CYP, but on collaborating with them to co-construct an informed and empowering understanding of poverty and its impact on their lives, to identify relevant solutions. In this context, participatory and artistic research was conducted using the

My Voice in Images methodology to access forms of knowledge, which have been rendered invisible by institutional frameworks and asymmetrical relationships between CYPs and adults. This methodology, in conjunction with the research findings, has led to the conception of a social innovation, as we will see later in this article.

3. Results

The research findings are presented in four sections. The first section attempts to (re)conceptualise child poverty on the basis of the experiences of CYP. The second section highlights the fragile trust that CYP place in social institutions and examines how these impact their evolving capacities, particularly their capability to aspire. The third section looks at the innovative social practices emerging from the voluntary social work sector, as identified during the fieldwork. The fourth and final section highlights the state’s underperforming social systems that have been the focus of institutional and political recommendations, prompting consideration for the need to develop a transformative social innovation project.

3.1. (Re)conceptualising Child Poverty on the Basis of the Experiential Knowledge of CYP to Define the Issue in a Fairer, More Equitable and More Inclusive Way

The conceptualisation and understanding of child poverty are crucial because they determine the political and social responses required to address it. The capability approach (

Sen 1999) provides an alternative and powerful conceptual framework. It offers a way to go beyond a measurement logic focused solely on material resources or deficits, by incorporating the notion of agency and examining the actual freedoms to express oneself, thereby opening up possibilities to choose, influence, aspire (

Appadurai 2004) and ultimately to lead a life one values.

Thanks to

My Voice in Images methodology, the voices of the CYP as “actions and performances which have a local cultural force” (

Appadurai 2004, p. 67), were brought to the forefront throughout the research process, revealing a multidimensional and interconnected experience of poverty. This experience spans a continuum from visible constraints apparent in material deprivation in the form of lack of housing, food, etc., to more subtle and silent experiences manifesting as feelings of exclusion and shame, lack of opportunities and lack of projection towards the future.

“What would you need to feel comfortable since you arrived here (emergency accommodation)? A house, a warm bed. A flat would be nice too”.

(Voice of the creators—Figure 5, photo workshop, 5–12 years old)

The

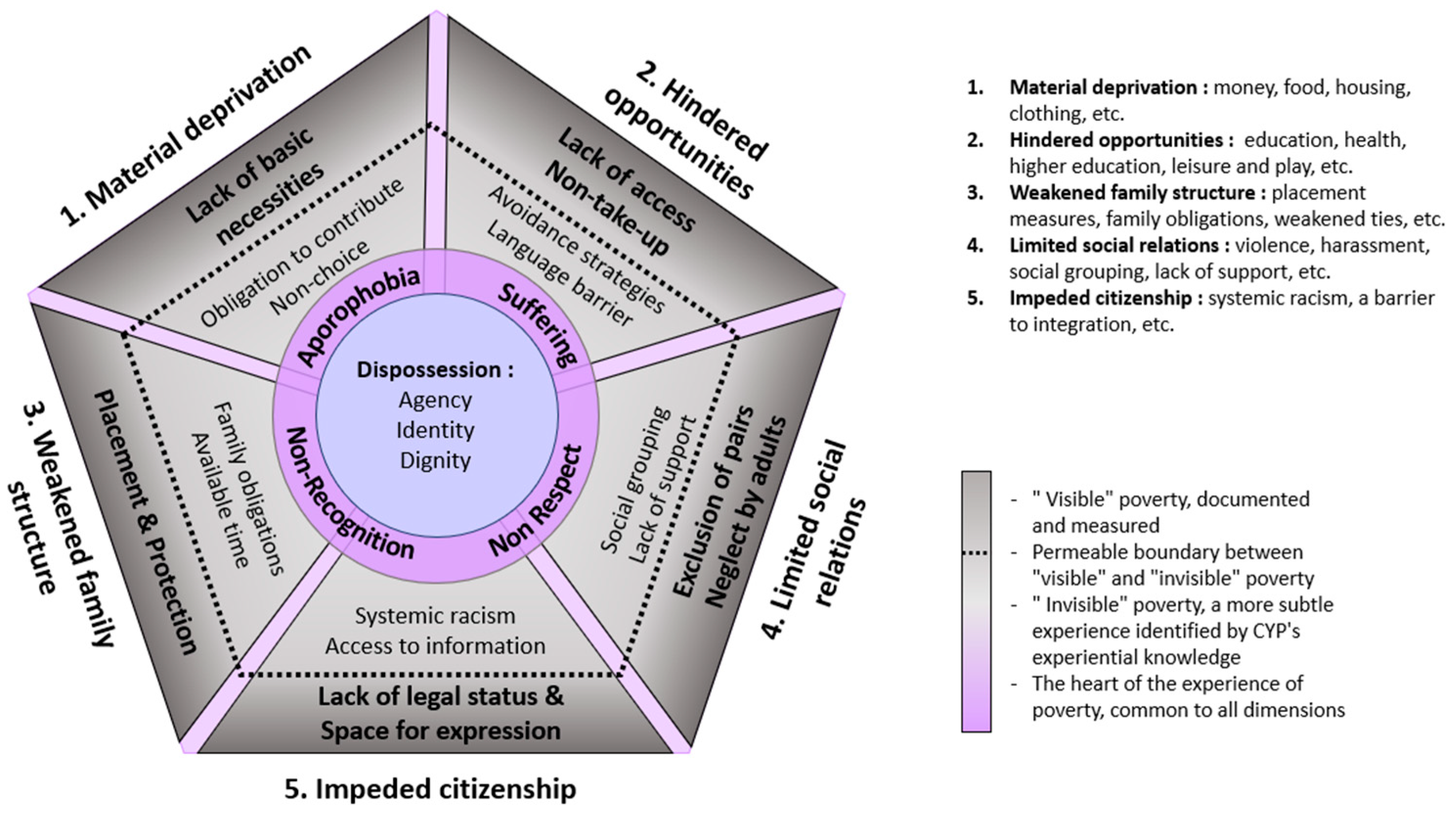

Figure 6 below highlights the five dimensions identified through the experiential knowledge of CYP, as well as the core of this experience marked by the dispossession of agency, identity and dignity.

The discourse of CYP consists of five distinct dimensions, each marked by gradual intensification that underscores the depth of the inequalities experienced: (1) material deprivation, (2) hampered opportunities, (3) weakened family framework, (4) limited social relationships and (5) impeded citizenship.

These five dimensions are often intertwined and underline the fact that child poverty is not simply a matter of material deprivation. It is embodied in complex experiences, constrained aspirations and intersecting forms of inequality and social exclusion. In the following section, we examine each dimension in greater detail, illustrating their interconnectedness and highlighting the solutions or conversion factors identified by CYP, drawing on the rich material that has been collected.

3.1.1. The Obligation to Contribute: An Example of the Interrelated Dimensions of Child Poverty

Economic difficulties and parental fatigue mean that CYP must take on responsibilities in the home, sometimes at a very early age: domestic chores, looking after siblings, etc.

The parents are fed up with work and debts, so they just sit around […]. […] In fact, the children cook and clean instead of their parents.

(Voices of the creators—Figure 7, image workshop, 7–13 years old)

This reversal of roles between CYP and adults is especially pronounced among girls, reflecting the gendered distribution of domestic responsibilities.

It takes time (the journey, the shopping). […] We help our parents. We still have to help each other. Our parents help us. So we have to help them too.

(Voices of teenage girls, image workshop, 11–14 years old)

CYP reflect on the challenges of balancing the time they dedicate to family responsibilities with the time needed for their own growth, particularly in terms of schooling and playtime. Performing these duties hinders their access to education and leisure, ultimately challenging their fundamental right to simply be a child.

For children who help their parents, it can help them to go to school and do extracurricular activities.

(CYP solution in relation to image 3, game workshop, 8-year-old)

Financial difficulties can also be observed in the parental sacrifice required to meet the basic needs of CYP.

What we wanted to create was for the children to have something on their plate (…) and the mum is happy to see her children eat but she’s sad because she can’t eat.

(Voice of creators—Figure 8, image workshop, 4–10 years old)

These two examples highlight how several dimensions, such as material deprivation, a weakened family framework and restricted opportunities, tend to be closely intertwined.

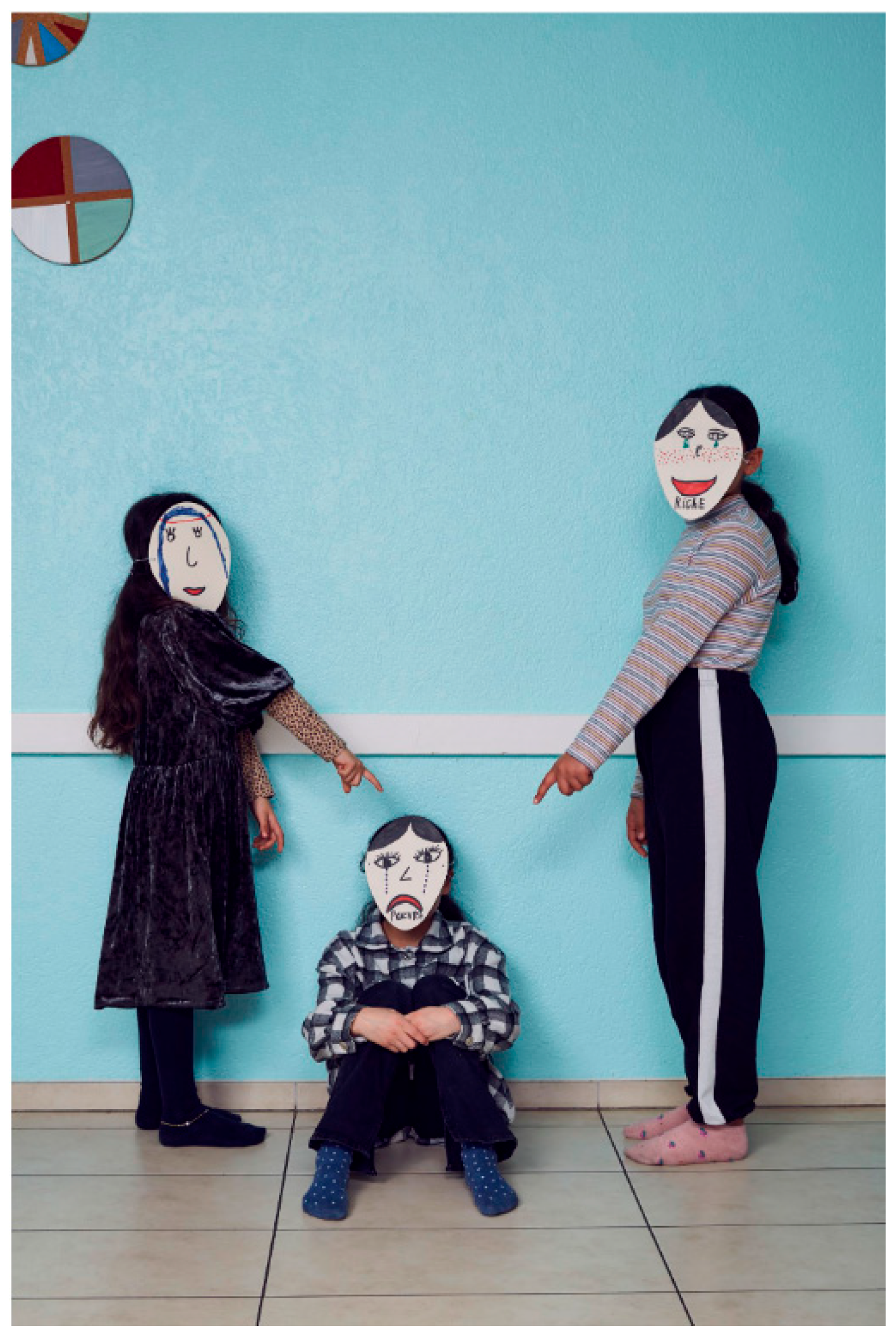

3.1.2. Limited Social Relationships: Between Avoidance Strategies and Experiences of Exclusion, Shame and Stigmatisation

CYP across all ages and genders emphatically lamented the limited scope for social relationships, which resulted in a strong sense of exclusion. In recounting their experiences of social inequality and discrimination, they emphasised loneliness and isolation associated with their precarious situations.

“There are rich people who make fun of poor people, and that makes them sad. “You have to be respectful and kind. You shouldn’t make fun of people who maybe don’t have enough money.”

(Voices of the creators—Figure 9, photo workshop, 6–10-year-olds)

Such discriminatory practices are often rooted in visible markers of social distinction, such as access to branded clothes or mobile phones, which are then ostentatious symbols of belonging and social inclusion with peer groups.

“I’d like to say to children who don’t have a snack at playtime: you mustn’t let people who make fun of you get you down, you mustn’t listen to them, what they say to you is just to see you cry, but you must be strong.”

(Voices of the creators—Figure 10, photo workshop, 7–10-year-olds)

For CYP, social relationships are also developed through interactions during leisure, cultural and/or sporting activities. These activities, considered vital for socialisation and personal development, are often rendered inaccessible for the children belonging to the most economically disadvantaged families due to the financial constraints of the poorest families. Moreover, participation in such activities becomes a visible marker of social inequality and a mechanism reinforcing exclusion, frequently exposing non-participants to mockery or even harassment at times, very often leading to social withdrawal. In response, some CYP, for example, resort to concealment or deception to avoid disclosing their real situation.

“In fact, he’s ashamed to say that he hasn’t got the money to go, so he says “I can’t, I’m busy”, when absolutely not (…) he just doesn’t have the financial means”.

(Voices of the creators—Figure 11, photo-workshop, 11–17-year-olds)

Through repeated avoidance of such situations, the children find themselves socially isolated, which hinders their ability to integrate with peers and form genuine friendships. The children express feelings of exclusion from their peer groups, which makes them feel ashamed.

“The children told me ’I’ve lost a lot of friends because I can’t go to the cinema or invite them to my house”. In fact, the other children ask: “Where do you live? And they’re a bit ashamed to say, ‘I live in the emergency shelter’. It’s a shame for them.”

(Social worker working in an emergency shelter for homeless families)

Thus, we see that the experience of poverty, as expressed through the voices of CYP, reveals feelings that impact their self-image and manifest in forms of self-exclusion driven by a deep sense of shame. These protective mechanisms, adopted to cope with their situation, clearly illustrate the limitations of the social relationships available to these CYP, as well as the internalisation of their difference resulting from their social status.

Such experiences recur consistently across all the collected data, regardless of participants’ age, background or place of reception. Therefore, they emerge as a cross-cutting and central feature of how poverty is experienced by CYP in Switzerland.

3.1.3. Denied Citizenship: Systemic Racism

Many times, experiences of exclusion are also linked to origin, migratory status or language, forming part of an aggravating systemic context. CYP describe challenges related to their difficulties in learning French, navigating Swiss social norms and achieving a sense of social integration.

“Because they don’t have the means. Because it’s difficult. Because they’re poor. Because no one helps them.”

(Voice of a child, game workshop, 8-year-old)

Beyond these language barriers, they denounce forms of structural racism in accessing training, housing or employment. However, their capability for social participation is constrained by the continued lack of acknowledgement of their presence and experiences, reinforcing their sense of marginalisation.

Finally, CYP describe an ambivalent relationship with public institutions, which they perceive as distant, judgmental and largely inaccessible. In the absence of spaces where their specific needs can be voiced, they often struggle to find the language to communicate their experiences.

We don’t talk about it much (poverty), and that’s why we didn’t have the words.

(Voice of a child, game workshop, 11-year-old)

This lack of recognition of CYPs’ experiential knowledge is an impediment for them to interpret their reality, which

Fricker (

1999,

2007) describes as hermeneutic injustice. The perception of being invisible, misunderstood or exploited by institutions and public policies is fuelling a growing distrust toward the systems intended to support them.

3.2. Fragile Trust in Institutions: What Capability to Aspire Through the Ages?

Analysis of the empirical data shows that CYP’s trust in social institutions and policies has been declining for some time. Among children, however, this trust still holds because it is supported by the belief that adults, whether family members, social welfare professionals or State representatives, act in their best interests, protect them and can therefore improve their daily lives.

In fact, it’s a poor person, someone gives him money, then the person on the left steals the money and the person on the right tells him to give the money back (first image of the diptych, Figure 12). So in the second image, it’s the social services that come and get the poor, give them food and house those who don’t have a home. (Voices of the creators—Figure 12, photo workshop, 8-year-old child)

Figure 12.

From the street to social welfare (diptych).

Figure 12.

From the street to social welfare (diptych).

As the children grow older, they are increasingly confronted with the inconsistencies of social systems, the ineffectiveness of certain public policies, the sluggishness of the administrative processes and stigmatising encounters with the institutions. These repeated experiences gradually erode CYP’s perception of the state and its capacity to provide effective support, to the point of engendering a feeling of disillusionment, or even resignation, in many young adults. This erosion of confidence is far from negligible; it has a direct impact on CYP’s sense of recognition, their power to act and their strength to pursue future possibilities.

We’re clowns in real life. Go on, they don’t care, they’re going to see it like that in real life, they don’t give a shit about it. There are articles and everything, there are documentaries and all that, it’s not two photos, go on, there’s no point in showing people in fact.”

(Voice of a young person living in emergency accommodation, 20 years old)

While the capability to aspire remains present among the children living in precarious conditions (in spaces like emergency shelters), this freedom tends to diminish over time and, in some cases, even disappears entirely by the time one reaches young adulthood. Opportunities for choice and influence (agency) are essential for enabling individuals to envision and work towards a better future. However, our findings indicate that these opportunities are systematically undermined by structural barriers and the discriminatory functioning of social institutions. As a result of this, many young people remain trapped in a survival mode, with limited hope and few viable pathways for leading a dignified life. An awareness of the time’s passage and the process of ageing, thus, becomes crucial. Young people realise that time is slipping away and gradually see their opportunities to be ahead diminish.

We’re still small. We’re not going to complain and cry about what’s happened to us and all that, because in reality, there are people who are waking up, and they’re already 30. They’ve just arrived and they’re looking for a job and a stable life, and they’ve already got kids and all that. It’s all over. We’re still young. You don’t want to end up lying in bed drooling on each other. That’s the risk. You don’t see yourself go; people who drool over themselves do not see they’ve gone one morning. No, it just happens. It’s from seeing the same thing over and over again, every day. One day you’re gone. Yeah, it’s tough.

(Voice of a young person living in emergency accommodation talking about addiction and precarious living conditions, 20 years old)

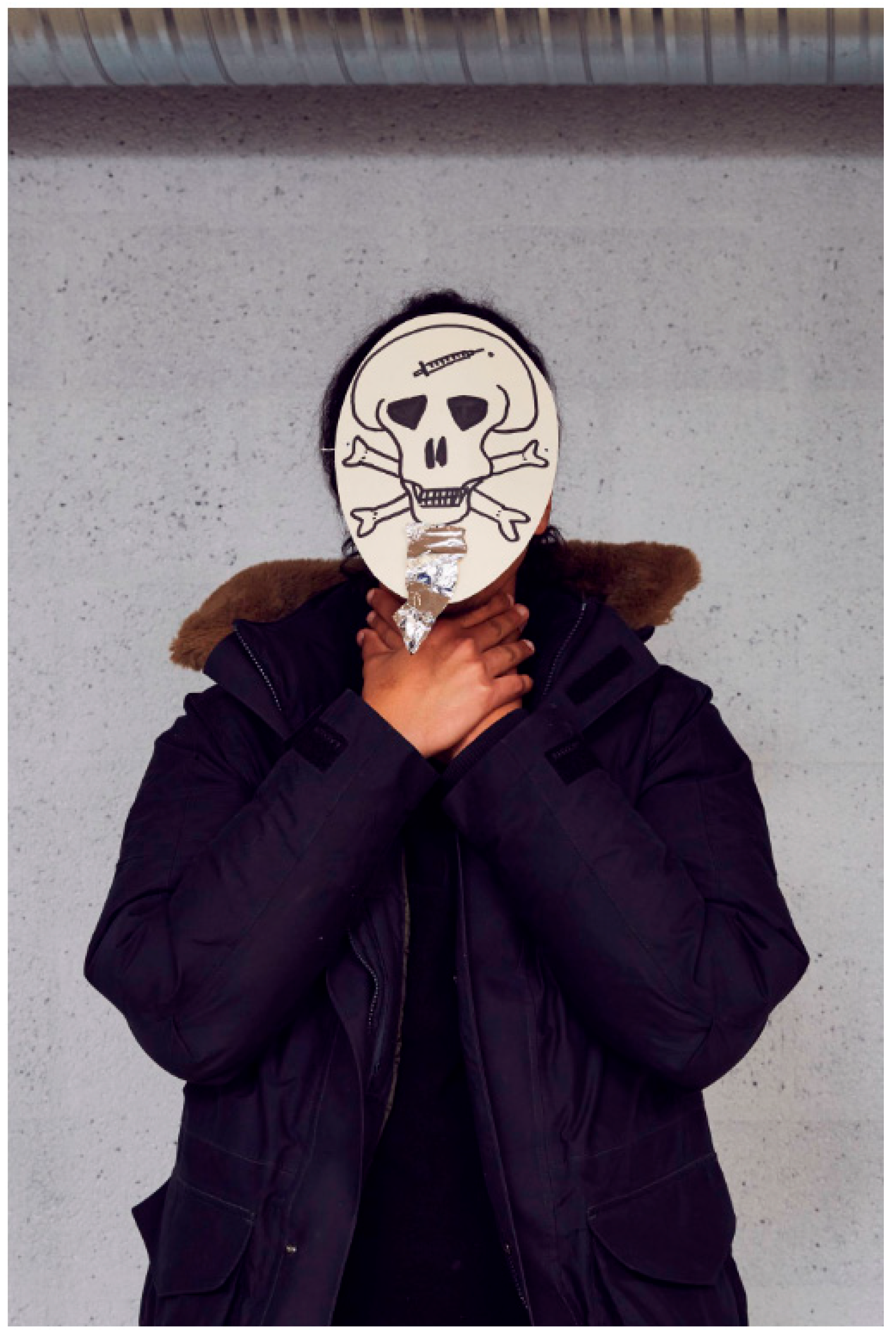

He’s alive, but in his head he’s dead’. We put a skull. Because this way of life leads to death anyway. If you stay like that for too long, you’re going to die. You can’t stay alive.

(Voice of creator—Figure 13, photo-workshop, 20 years old)

3.3. Some Inspiring Social Practices That Demonstrate the Potential of Social Work to Support Evolving Capabilities of CYP

Social Work practice displays great potential for empowering, emancipating and ensuring social inclusion of its target groups, including CYP, as was observed during the fieldwork for this study. By engaging in the transformation of public policies and professional practices, social work can serve as a strategic lever for enhancing the evolving capabilities of CYP. Notably, two innovative practices, pre-existing to the research and implemented by community-based associations encountered in the field, emerge as particularly significant in this regard. The first initiative is that of ‘supported family holidays’, which brings together parents and CYP from disadvantaged backgrounds who are subject to protection measures (

Garcia Delahaye and Dubath 2023b). The second is ‘modular individualised support’ designed within emergency accommodation settings for families (

Garcia Delahaye and Dubath 2024)

8 These two forms of practice constitute particularly significant and generative sources for the continuation of future work. Indeed, these two examples illustrate the capacity of social work practice to cultivate spaces of choice, influence and recognition for beneficiaries. The provision for ‘tailor-made’ support enables a more nuanced understanding of individual needs, while actively affirming and promoting their capability to express themselves (capability for voice) in the context of social support. It guarantees the development of services tailored to the choices of beneficiaries, and they are shaped by their capability to influence evolving social systems. At the heart of these innovative practices is the socio-cultural approach (

Garcia Delahaye 2024)

9, an intervention model grounded in principles of active participation, voluntary engagement, and the bond of trust forged between the social workers and the individuals whom they support.

What these two innovative practices also have in common is the development of more agile models of individual and collective support for impoverished and marginalised populations, based on their right to participate. These associations employ diverse strategies to address complex issues. However, their interventions are rooted in the need to forge and strengthen links both within families made vulnerable by poverty and at the community level. These links have been weakened by the persistent taboo (

Ostorero 2007) surrounding poverty in Switzerland and by the discrimination endured, which often leads people to withdraw into themselves. It is essential to reconstruct these links, not only for gaining recognition but also to enable CYP to recognise themselves as (re)valued members of the group/community, despite the experiences of alienation. CYP widely recognise the significance of the work undertaken by these associations and emphasise the importance of the family within a community that values its worth.

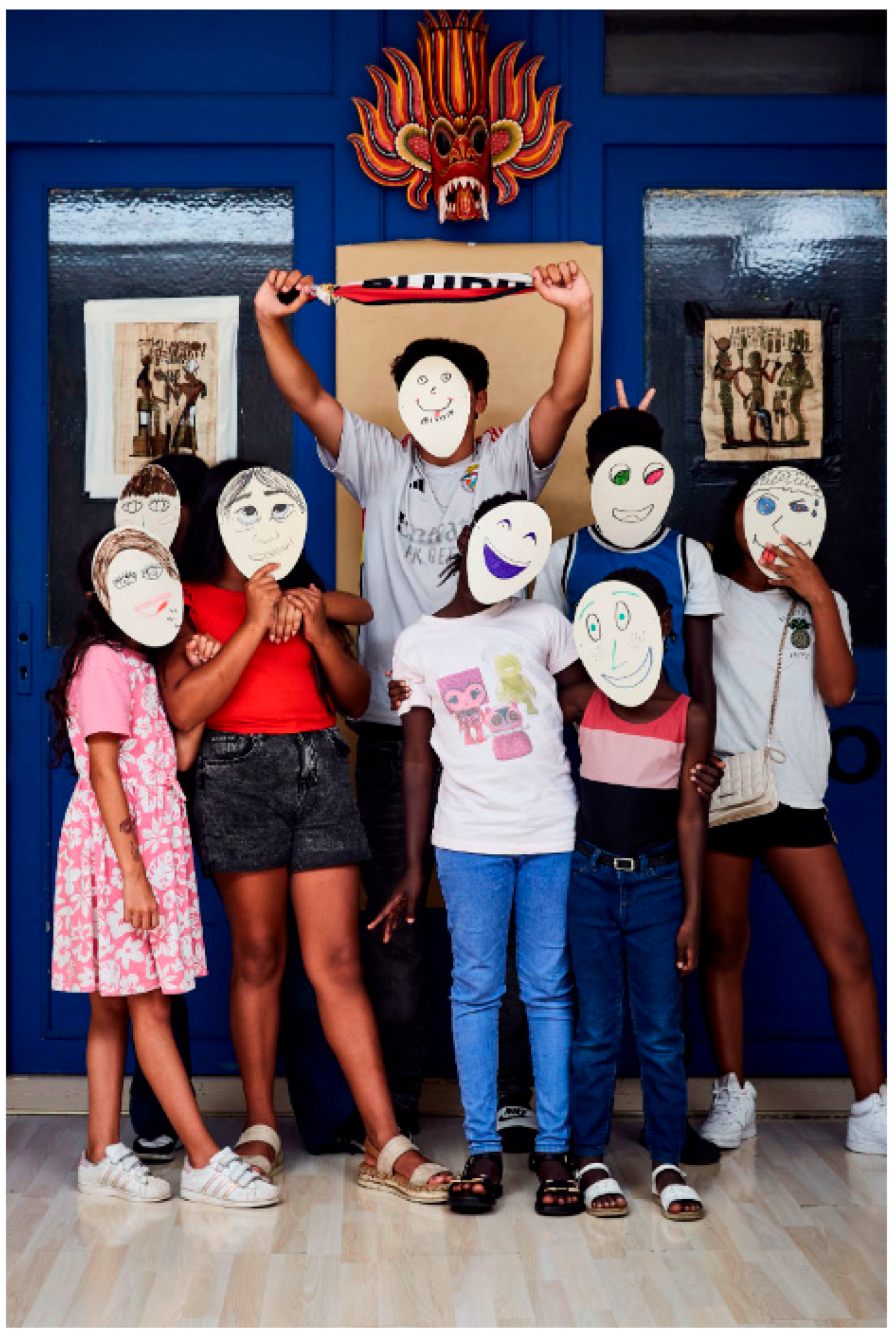

Together, we’re stronger. Everyone (the community, the group) is happy. Everyone is happy (to be together). It’s pure happiness”

(Voices of seven creators—Figure 14, photo workshop, 5–16 years old)

For the CYP, the group, the community, represents the most significant and ‘reliable’ level for finding solutions to the problems identified. For this reason, they tend to view the community level as a key conversion factor, assuming a degree of intra-group responsibility as a means of coping while simultaneously showing a degree of mistrust towards the public institutions that have, until now, extended limited or no support (

Garcia Delahaye and Dubath 2024).

These two examples of innovative practice demonstrate the necessity and potential for social work to reposition individuals, including CYP, back at the heart of its work, recognising them as active entities not only in determining the course of their own lives, but also in terms of contributing to their community and society as a whole, and consequently the systems and policies that target them.

3.4. Underperforming Social Intervention Systems: The Case of Social Welfare Institutions

Despite the community-level organisation’s innovative practices, the research findings point towards underperforming social intervention mechanisms that render the experiences of CYP invisible, and perpetuate epistemic injustices perpetrated by major social institutions against this age group (

Schües 2016, pp. 168–69;

Fricker 1999,

2007). This is particularly evident within state welfare services, which have recently acknowledged the need to engage with CYP, who, as an age group (0–25 years) represent 40% of welfare recipients in Switzerland (

OFS 2023). Although the standards of the Swiss conference of social welfare institutions are currently under revision, stipulating that special attention must now be paid to the proper development of children and adolescents (

CSIAS 2024, p. 5), social welfare institutions continue to reproduce the structural asymmetry between adults and CYP in social intervention. CYP’s difficulties and aspirations are mainly reported by the parents, as social welfare, like most social services, is conceived by and/or for adults. Consequently, assessment of the family situations fails to incorporate the views of CYP affected by poverty, despite their inclusion as members of the family unit in benefits calculation and their inevitable transition into direct recipients of social welfare when they come of age, perpetuating an intergenerational cycle of poverty.

This concerning finding provided the basis for recommendations and sustained dialogue with welfare institutions at both national and cantonal level (

Garcia Delahaye et al. 2024, pp. 27–28)

10. Grounded in state conversion factors identified by CYP and by professionals in this field, these recommendations (

Table 1) are structured around the three pillars of child and youth policy in Switzerland (protection, encouragement and participation) and the provisions of the International Convention on the Rights of the Child (

Garcia Delahaye et al. 2024, p. 27).

As a result of the efforts to achieve the political and institutional recognition for the research findings, it has become evident that the current social intervention mechanisms (particularly social welfare) are struggling to evolve due to the absence of intervention models that promote: (1) the concrete operationalisation of the participation of CYP (

Garcia Delahaye et al. 2024;

Höglinger et al. 2024), (2) the strengthening of their capabilities, in particular to express themselves (capability for voice) and to aspire to a better life (

Appadurai 2004;

Zimmermann 2024); and (3) the evaluation of the real contributions of this participation for social work practice. Without these three core elements, such mechanisms cannot become real drivers of social justice.

4. Discussion

This research highlights both the challenge and the opportunity that the participation of CYP presents for social work practice. It also examines the adverse consequences of the lack of participatory methodologies adapted to CYP to conduct social intervention, particularly in terms of impeding the flourishing development of their evolving and dynamic capabilities (

Ballet et al. 2011;

Biggeri et al. 2011;

Stoecklin and Bonvin 2014). In the current design of the available services within social work practice, formal rights of CYP are hardly ever translated into effective freedoms (

Sen 1992) due to the systematic neglect of their voices and the insufficient recognition of their roles as active agents.

To move beyond these limitations, the article proposes the conditions necessary for the development of a new paradigm of social work practice, which can more effectively combat intergenerational transmission of poverty. Drawing on the research findings, the article explores the possibility of creating a transformative social innovation project with CYP and social workers. Through this imagined innovation, we will reassess the role of social work practice as a concrete means of supporting the dynamic development of CYP’s evolving capabilities, which comprise three constituent dimensions: opportunity, capacity and agency (

Ballet et al. 2011, p. 23). With reference to our research process, we will be focusing more specifically ability of social workers (as key social agent (

Schweiger and Graf 2015)) to help the CYP raise their capability for voice, the extent of their opportunities for choice and influence (agency) within the context of a social intervention aimed at the effective participation of service users; and the boarder impact that such an approach would have on the potential capability set (

Trani et al. 2011;

Ballet et al. 2011;

Biggeri and Santi 2012) especially, their capability to aspire.

4.1. Towards a New Paradigm of Social Work Practice to Break with the Fatality of Inherited Poverty

Since poverty in Switzerland is intergenerational (

Garcia Delahaye and Dubath 2023a,

2023b), the social protection systems understood as structural conversion factors shaped by the living environment of the CYP (State, national and cantonal policies and institutions) (

Trani et al. 2011), play a crucial role in combating this societal problem and the marginalisation of the most vulnerable groups. However, current social interventions, based mainly on the minimum subsistence level approach and the principle of social control (

Castel 1995), contribute to the reproduction of social inequalities and reinforce the stigmatisation, marginalisation (

Simmel 1998) and rejection of the populations concerned (

Cortina 2023). These systems are embedded within structural power dynamics that shape the life trajectories of vulnerable families, thereby entrenching inequalities over time (the legacy of poverty) and fostering a sense of dispossession. Drawing on the work of

Schweiger and Brando (

2021), there is a necessity of moving beyond the current paradigm of the remedial assistance model, and to devise a genuine concept of ‘social investment’ to support the evolving capabilities of CYP. This requires recognising CYP not merely as future adults or economically productive and socially insertable individuals, but as citizens and social agents in their own right.

While the participation of poor adults has recently been acknowledged as essential for the relevance and effectiveness of social interventions and public policies concerning them (

ATD 2023), the participation of CYP is still limited or even stagnating due to entrenched asymmetrical power relations between adults and CYP. The goal is not to romanticise the participation of CYP, but rather to critically examine the methodological, ethical and institutional conditions that enable or prevent its effective operationalisation (

Schweiger 2025). This paradigm shift in social action with CYP requires the development of new models of intervention grounded in transformative public policies. These should not simply mitigate the effects of poverty (adopt a reparative approach), but actively address its root causes by redistributing resources, correcting structural inequalities and opening up spaces for effective participation (

Sen 1999;

Arnstein 1969) and recognising social work audiences. Such a shift implies rethinking the aims and objectives of social action and the logic that underpins it through its institutions and professional practices. The objective is no longer confined to providing support or temporary relief but extends to fostering the emancipation and recognition of CYP as social actors whose lived experiences are vital to understanding and addressing social issues. This entails co-creating and testing, along with CYP, appropriate spaces and tools/models of intervention to support their evolving capacities, empowering them to make informed choices about existing and future social services to shape public policies and systems that affect them.

The research findings highlight the need for systemic innovation that integrates research and its methodologies with professional practice and its intervention models, as well as the public policies that shape them. This integrated approach must foster collective learning and constructive transformation. Such an approach also requires greater inter-institutional collaboration to overcome siloed thinking and calls for cross-disciplinary efforts to promote equal opportunities, inclusion and empowerment for CYP (

Garcia Delahaye et al. 2024).

4.2. Issues of CYP’s Participation in Social Work, with Reference to the Capability Approach

Before presenting the transformative social innovation that has been imagined, it is important to highlight a few issues relating to the participation of CYP in social work, with reference to the Capability Approach.

The need for public participation in social work has been explored by several authors in Switzerland (

Bonvin 2012;

Bonvin and Laruffa 2024;

Gerodetti 2022) through

Amartya Sen’s (

1999) Capability Approach, which provides a robust philosophical framework for evaluating social intervention, including that carried out with CYP (

Biggeri et al. 2011;

Stoecklin 2018). This approach prioritises systems that focus on developing capabilities and empowering people rather than according to significance to ‘classic’ practices of reinforcing control, constraint and even coercion towards the poor (

Simmel 1998). According to

Sen (

1992), the search for solutions (conversion factors) to social problems, as well as the definition of real capabilities (freedoms to lead the desired life) and those to be strengthened, can only be undertaken through democratic dialogue between the various stakeholders (including CYP and social workers). This approach recognises the positional objectivity of individuals, acknowledging the difficulties of participation being linked to personal characteristics such as age, social class and gender, as well as the adaptive preferences that are derived through them (

Sen 1992).

For CYP, the International Convention on the Rights of the Child takes into account the evolution over time of their capabilities, in relation to adults in particular, advocating a dynamic understanding of capability development (“from being to becoming”) (

Ballet et al. 2011;

Biggeri et al. 2011;

Stoecklin 2018). Therefore, close attention must be paid to the participatory spaces created within social work so as to avoid replicating the deliberative, preconceived notions perpetuated by adults that reinforce inequality among CYPs, fracturing their voice while keeping them deluded with meaningless prospects of choice and influence.

The operationalisation of CYP’s participation in social systems is a prospect that encounters major challenges. This concept, essential in the social sciences, has multiple definitions. Therefore, in the context of a transformative social innovation project, it needs to be clarified that laying the foundations for a social intervention that complies with children’s rights. First of all, Arnstein’s Ladder of Participation (

Arnstein 1969), analysed by

R. A. Hart (

1990) with reference to the International Convention on the Rights of the Child, aims at three progressive levels of participation in democratic processes: (1) non-participation or alibi participation, (2) symbolic participation; and (3) real/effective participation. This last level is based on a more balanced power dynamic between CYP and adults, encouraging the former to take initiatives and make decisions. Inspired by this scale,

Shier’s (

2001) pathways to participation verify three levels of commitment by professionals and institutions to the effective participation of CYP: (1) openness to participation, (2) concrete opportunities for participation and (3) institutional obligations. Proposed by

Shier (

2001), this model serves as a practical tool for evaluating the integration of ‘participation’ in social work practice. Finally, the Lundy Model of Child participation (

Lundy 2007) identifies the essential prerequisites for effective participation, such as the creation of suitable spaces and support systems and invites us to reflect on the concrete means of participation to be implemented.

These models of participation form the core of the transformative social innovation that has been imagined through the course of our research, which aims to actively integrate the voices of CYP throughout the social intervention process.

4.3. Towards Transformative Social Innovation

Emerging from the latest trend in Childhood Studies, based on the capability approach, several studies on child poverty have demonstrated that it is possible to identify, in specific contexts, the deprivations faced by CYP and the freedoms that need to be strengthened (

Garcia Delahaye et al. 2024, Garcia Delahaye and Dubath 2024;

Bessell 2021;

Biggeri and Mehrotra 2011). Some of these studies, including our own, highlight the importance of methodology in providing detailed insights into child poverty and practical models and strategies for its prevention or elimination (

Garcia Delahaye et al. 2024, Garcia Delahaye and Dubath 2024;

Bessell 2021). The methodological foundation of this research rests on three core principles: (1) developing a child-centred methodology; (2) adopting an action-oriented approach for ethical and political reasons; and (3) employing an inclusive epistemology that recognises children’s knowledge as unique and essential for understanding existing inequalities and identifying ways to address them. These three principles, relevant to research with socially disadvantaged CYP, appear to us to be crucial for developing innovations that can inform social intervention.

The innovation envisioned aims to move beyond any deterministic or fatalistic view of social intervention by proposing, throughout the support process, an in-depth co-analysis of potential reconfigurations concerning voice, choice, and influence (agency) of the CYP who benefit from social work, as well as the logic of action and supply (services) of the involved institutions and public policies. This co-analysis will be implemented as part of an upcoming applied research project conducted within social welfare organisations with a focus on emancipation and reflection. The aim of such a project is precisely to test, with the participants (CYP and social workers), a new intervention tool/model that continuously assesses the real impact of CYP’s participation on their agency (possibilities of choice and influence) as actors in social work and ultimately on their evolving capabilities.

This innovation, which is part of the new transformative paradigm of social work practice described above, therefore aims to better understand, on the one hand, from social services, the process of supporting the evolving capabilities of CYP, particularly their capability for voice and to aspire to a better life, and, on the other hand, the potential for strengthening professional practice through the effective participation of CYP and enhancing their role as active agents. As our research results have shown a significant decline in aspirations with age, this envisioned transformative social innovation project could offer new opportunities both to CYP, by expanding their capabilities through an empowering relationship with social workers, and to the social workers themselves, through more effective social practices.

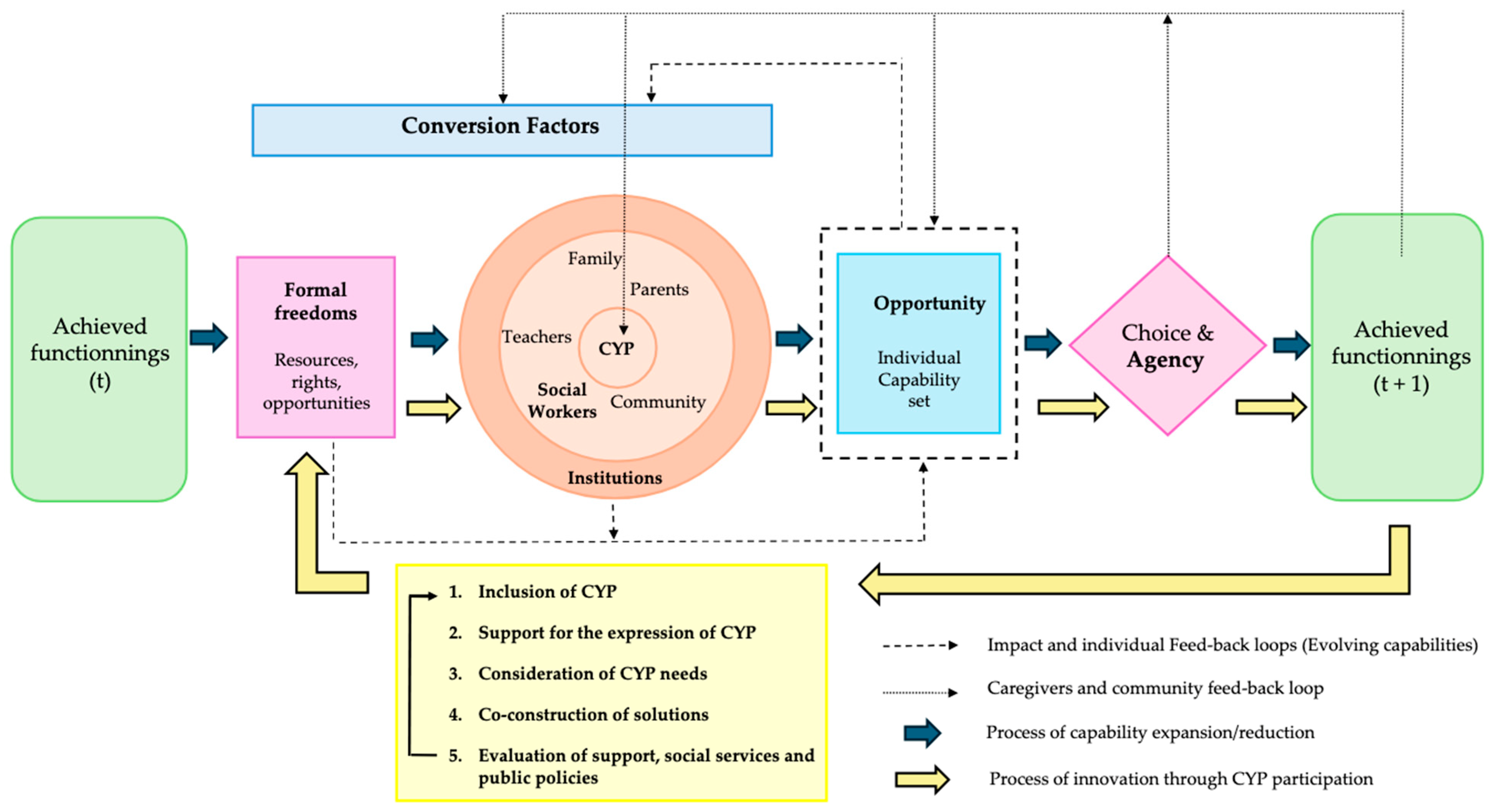

The

Figure 15 below illustrates the process of implementing transformative social innovation through the application of the Capabilities Approach to the social work field with socially disadvantaged CYP. It emphasises the establishment of a balanced relationship with social workers, based on the effective participation of the public, in terms of the models of participation presented above.

The

Figure 15 highlights the importance of strengthening the conversion factors embedded in institutional structures, particularly at the levels of the State and cantons to where social intervention and public policies are situated. This must be carried out to support the evolving capabilities of CYP more effectively. The research findings have indeed demonstrated a major weakness at this level, particularly in the domain of social welfare, which is also widely recognised by social workers in this field (

Garcia Delahaye et al. 2024). This diagram also illustrates the central role that CYP must play in their own development process, by continuously interacting with other agents, particularly social workers, whose role is critical to the extension of capabilities and fostering self-determination and agency (

Sen 1992,

2009). As Biggeri and Santi point out, “agency is essential to exert one’s participation and to regulate his/her own behaviour by defining a series of operations, which enable him/her to reach a potential desired condition” (

Biggeri and Santi 2012, p. 379).

The aim of social innovation is to implement an integrated model of social intervention capable of producing lasting and transformative outcomes with the effective participation of CYP not only at the individual level (the heart of the action,

Figure 15) but also at family, community, institutional and political levels. Since social work operates across all these levels, it can have a multifaceted impact by considering the problems expressed, addressing dimensions of poverty, access to services, and recognising the choices and aspirations of CYP in congruence with other agents. This requires a practical, institutional and political approach to social work that allows CYP to develop capabilities to aspire through their involvement in the decision-making process where they are considered as members of the public with the potential to be part of the social contract (

Ballet et al. 2011). The proposed innovation is part of a transformative social action rationale, based on the concrete strengthening of opportunities for choice and influence and of capabilities for voice and to aspire of CYP, thereby advancing their full potential in relation to social agents (social workers), social institutions and public policies.

5. Conclusions

The (re)conceptualisation of child poverty proposed in this article, together with the dimensions identified by the CYP, provides a framework for studying and exploring in greater depth, not only this problem but, above all, the solutions applicable in both richer and less rich countries.

Conceptualising child poverty and determining the appropriate social responses to tackle it requires moving beyond a mere managerial approach or simple remedial social interventions. While social work can mitigate the precariousness of their situation to some extent, a real contribution to social justice is only possible if it adopts a transformative approach, capable of questioning the structures that produce and reproduce poverty across generations.

The results of this research demonstrate that within social services, the capability for voice and the opportunities for choice and influence play a fundamental role in enabling social work beneficiaries to aspire. While children and adolescents retain the capability to dream of a better life and believe in their future to some extent, the young adults appear to be shaped by renunciation and a sense of resignation stemming from a combination of structural barriers and disheartening institutional experiences. This contrast underscores the importance of early intervention to prevent disruption and eventual breakdown in the processes that facilitate the development of identity and citizenship.

This highlights the imperative for public policy to critically reassess its role and to integrate innovative approaches within social work practice to achieve genuinely transformative outcomes. Central to this process is recognition of CYP as active agents, ensuring their needs are articulated and their voices meaningfully inform the policies shaping their future. Merely enabling individuals to envision alternative possibilities is practically inadequate. These futures must also be perceived as attainable. An absence of such perceived accessibility and plausibility engenders a sense of powerlessness among CYP, constraining their capability to aspire.

Implementing the right to participation, as a form of cognitive and social justice (

De Sousa Santos 2014), from within social institutions, requires a profound change. The challenge lies not merely in reforming existing policies, but in reimaging the very processes through which they are constructed, by engaging with the people directly affected. Social work, in its applied dimension, offers a strategic field for this purpose. This entails recognising CYP not just as beneficiaries of social policies but as active participants in the larger developmental process with capabilities, aspirations and rights.

With this in mind, the Capability Approach (

Sen 1992) enables reconceptualisation of the social institution not merely as a site of normative enforcement, but as a space where the agency, choice and influence of public actors in social work can be exercised and realised. A public policy becomes genuinely transformative only when it facilitates the productive participation of those directly affected by it in its conceptualisation and design. From this point of view, social work as a discipline must move beyond mere implementation of prescribed measures and position itself as a catalyst for social innovation and transformative change at individual, institutional and societal levels. Realising this potential necessitates sustained advocacy, critical awareness-raising and strategic action.

We need to design systems that foster self-expression, empower individuals to act and enable them to envision and pursue the future (the capability to aspire). This must occur in close conjunction with a reconfiguration of public policies oriented towards greater justice, inclusivity and equality. Designing such systems requires an inclusive construction approach, in which the experiential knowledge of CYP plays a central role in defining the responses to social inequalities.

Lastly, transforming institutional practices also requires embedding them within a sustainability framework. Enabling CYP to express their voices should not be viewed as a cost, but rather as a strategic investment. While it may entail short-term implementation expenses, it yields long-term benefits by reducing the risks of social disaffiliation, enhancing the effectiveness of the services and restoring trust in institutions.