Digital Technologies for Young Entrepreneurs in Latin America: A Systematic Review of Educational Innovations (2018–2024)

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Sociocognitive Foundations of Digital Entrepreneurial Learning

1.2. Connectivism and Distributed Learning Architectures

1.3. TPACK: Technological, Pedagogical, and Entrepreneurial Integration

1.4. Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy in Digital Contexts

1.5. Integrated Models of Digital Entrepreneurial Competencies

1.6. The Theory of Digital Entrepreneurial Ecosystems

1.7. Technology Acceptance and Adoption Models

1.8. Theoretical Integration and Latin American Context

1.9. Alignment with the Sustainable Development Goals

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Search Strategy and Information Sources

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

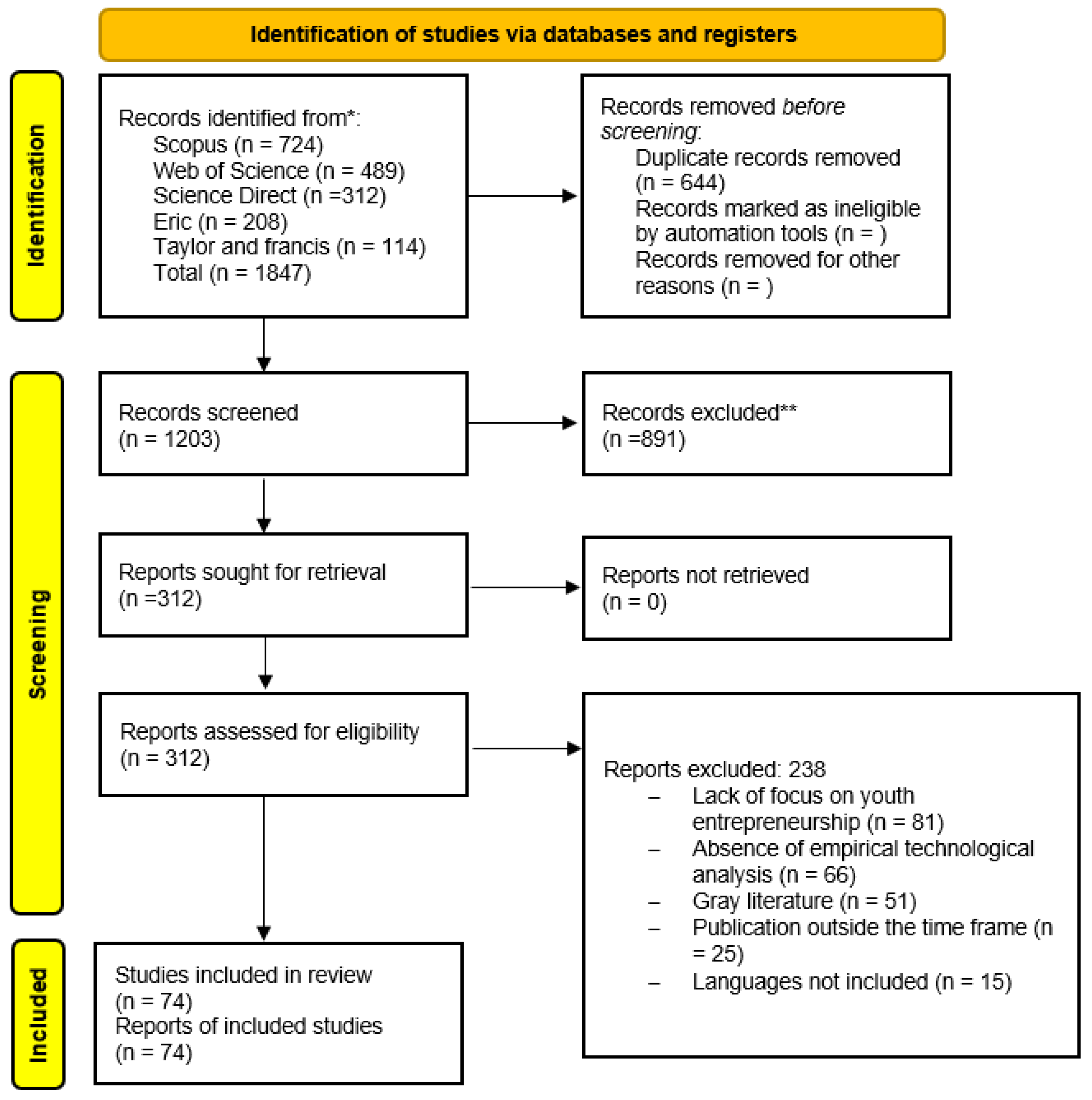

2.4. Study Selection Process

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Methodological Quality Assessment

2.7. Synthesis and Analysis of Data

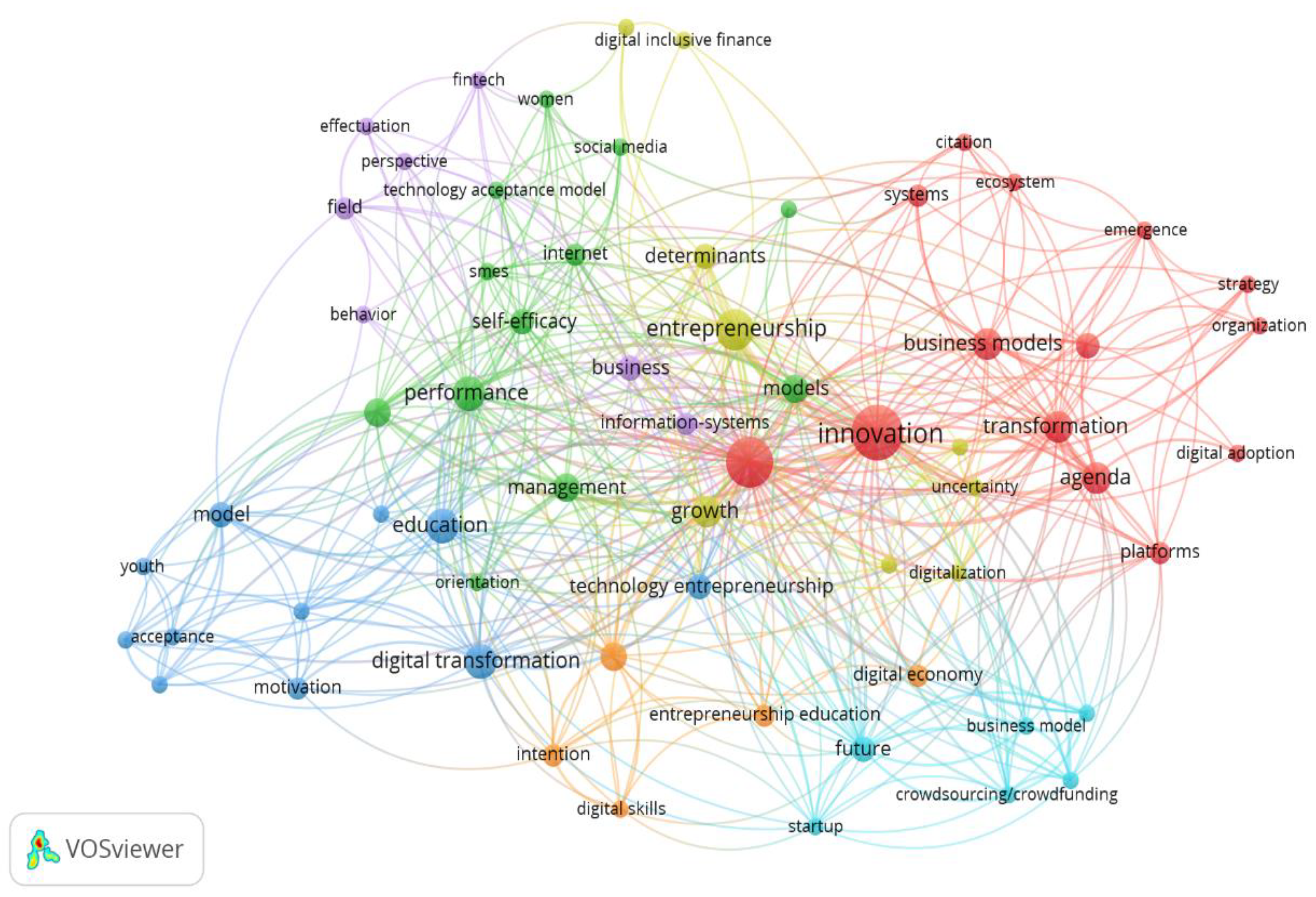

2.7.1. Complementary Bibliometric Analysis

2.7.2. Structured Narrative Synthesis

2.8. Limitations

2.9. Ethical Considerations and Transparency

3. Results

3.1. Technological Landscape of Youth Entrepreneurship in Latin America

3.2. Differentiated Patterns of Entrepreneurial Effectiveness

3.3. Theoretical Convergence and Links with Sustainable Development

3.4. Technological Landscape of Youth Entrepreneurship in Latin America

3.5. Differentiated Patterns of Entrepreneurial Effectiveness

3.6. Structural Gaps and Innovative Adaptations

3.7. Theoretical Convergence and Linkages with Sustainable Development

3.8. Digital Technologies for Youth Entrepreneurship in Latin America: Systematic Review (2018–2024)

4. Discussion

4.1. Convergence of Transnational Evidence and Parametric Differentiation

4.2. Epistemic Architecture of the Field: Bibliometric Triangulation and Empirical Validation

4.3. Operationalization of “Innovation by Constraint”: Transdisciplinary Conceptual Synthesis

4.4. Differential Effectiveness and Contextual Mediation: Robust Empirical Confirmation

4.5. Implementation Gaps: Structural Confirmation of the Third Hypothesis

4.6. Implications for the Development of Transdisciplinary Educational Policies

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adams, Glenn, Sara Estrada-Villalta, and Luis H. Gómez Ordóñez. 2018. The modernity/coloniality of being: Hegemonic psychology as intercultural relations. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 62: 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allal-Chérif, Oihab, José Manuel Guaita-Martínez, and Eduard Montesinos Sansaloni. 2024. Sustainable esports entrepreneurs in emerging countries: Audacity, resourcefulness, innovation, transmission, and resilience in adversity. Journal of Business Research 171: 114382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, Paulo, Paul Leger, and Isotilia Costa Melo. 2024. Efficiency analysis of engineering classes: A DEA approach encompassing active learning and expositive classes towards quality education. Environmental Science & Policy 160: 103856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancheta-Arrabal, Ana, Cristina Pulido-Montes, and Víctor Carvajal-Mardones. 2021. Gender Digital Divide and Education in Latin America: A Literature Review. Education Sciences 11: 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andonova, Veneta, and Juana García. 2018. How can EMNCs enhance their global competitive advantage by engaging in domestic peacebuilding? The case of Colombia. Transnational Corporations Review 10: 370–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbeláez-Rendón, Mauricio, Diana P. Giraldo, and Laura Lotero. 2023. Influence of digital divide in the entrepreneurial motor of a digital economy: A system dynamics approach. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 9: 100046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, Ahmad, Bonnie G. Buchanan, Samppa Kamara, and Nasib Al Nabulsi. 2021. Fintech, base of the pyramid entrepreneurs and social value creation. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 29: 335–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, Guilherme, Jorge Carneiro, Carlos Rodriguez, and Maria Alejandra Gonzalez-Perez. 2020. Rebalancing society: Learning from the experience of Latin American progressive leaders. Journal of Business Research 119: 511–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, Joern H., Massimo G. Colombo, Douglas J. Cumming, and Silvio Vismara. 2021. New players in entrepreneurial finance and why they are there. Small Business Economics 50: 239–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, Andrew, Anthea Sutton, and Diana Papaioannou. 2022. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review. Thousand Oaks: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Bravo-Ortega, Claudio, Pablo Egana-delSol, and Nicole Winkler-Sotomayor. 2023. Does the lack of resources matter in a dual economy: Decoding MSMEs productivity and growth. Economic Analysis and Policy 80: 716–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brixiová, Zuzana, Thierry Kangoye, and Mona Said. 2020. Training, human capital, and gender gaps in entrepreneurial performance. Economic Modelling 85: 367–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgos, Daniel, and John Willian Branch, eds. 2021. Radical Solutions for Digital Transformation in Latin American Universities: Artificial Intelligence and Technology 4.0 in Higher Education. Singapore: Springer Singapore. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Spila, Javier, Rosa Torres, Carolina Lorenzo, and Alba Santa. 2018. Social innovation and sustainable tourism lab: An explorative model. Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning 8: 274–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirambo, Dumisani. 2018. Leaving No-One Behind: Improving Climate Change and Entrepreneurship Education in Sub-Saharan Africa Through E-Learning and Innovative Governance Systems. In Climate Literacy and Innovations in Climate Change Education: Distance Learning for Sustainable Development. Edited by Ulisses M. Azeiteiro, Walter Leal Filho and Luísa Aires. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Giudice, Manlio, Alexeis Garcia-Perez, Veronica Scuotto, and Beatrice Orlando. 2019. Are social enterprises technological innovative? A quantitative analysis on social entrepreneurs in emerging countries. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 148: 119704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, Naveen, Satish Kumar, Debmalya Mukherjee, Nitesh Pandey, and Weng Marc Lim. 2021. How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research 133: 285–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downes, Stephen. 2020. Recent Work in Connectivism. European Journal of Open, Distance and E-Learning 22: 113–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, Cong, and Thanh Nguyen. 2024. How ChatGPT adoption stimulates digital entrepreneurship: A stimulus-organism-response perspective. The International Journal of Management Education 22: 101019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzator, Janet, Alex O. Acheampong, Isaac Appiah-Otoo, and Michael Dzator. 2023. Leveraging digital technology for development: Does ICT contribute to poverty reduction? Telecommunications Policy 47: 102524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean [CEPAL]. 2022. Social Panorama of Latin America and the Caribbean 2022: The Transformation of Education as a Basis for Sustainable Development|Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. Available online: https://www.cepal.org/es/publicaciones/48518-panorama-social-america-latina-caribe-2022-la-transformacion-la-educacion-como (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Ferrante, Patricia, Federico Williams, Felix Büchner, Svea Kiesewetter, Godfrey Chitsauko Muyambi, Chinaza Uleanya, and Marie Utterberg Modén. 2024. In/equalities in digital education policy—Sociotechnical imaginaries from three world regions. Learning, Media and Technology 49: 122–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frimpong, Stephen. 2024. Against Democracy, Neo-totalitarianism, or What? A Cross-Country Dynamic Panel Endogenous Switching Regressing Analysis of Innovation, Economic Growth, and Political Stability. World Development Perspectives 36: 100625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Peñalvo, Francisco J., and Alfredo Corell. 2020. La COVID-19: ¿enzima de la transformación digital de la docencia o reflejo de una crisis metodológica y competencial en la educación superior? Campus Virtuales 9: 83–98. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Tamayo, Lizbeth A., Greeni Maheshwari, Adriana Bonomo-Odizzio, and Catherine Krauss-Delorme. 2024. Successful business behaviour: An approach from the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT). The International Journal of Management Education 22: 100979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, David, Sandy Oliver, and James Thomas. 2020. An Introduction to Systematic Reviews. Thousand Oaks: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Grzeslo, Jenna. 2020. A generation of bricoleurs: Digital entrepreneurship in Kenya. World Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development 16: 403–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumbi, Nolwazi, and Thea Van Der Westhuizen. 2020. Youth Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy Towards Technology for Online Business Development. Paper presented at the 16th European Conference on Innovation and Entrepreneurship, Krakow, Poland, September 25–26; pp. 283–91. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/1503caff36253c71a6b02078cda79ef0/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=396494 (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Haji, Karine. 2021. E-commerce development in rural and remote areas of BRICS countries. Journal of Integrative Agriculture 20: 979–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Ying, and Rand J. Spiro. 2021. Design for now, but with the future in mind: A “cognitive flexibility theory” perspective on online learning through the lens of MOOCs. Educational Technology Research and Development 69: 373–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inter-American Development Bank. 2020. The Youth Entrepreneurship Programme in Latin America and the Caribbean: Impact Report. Washington, DC: IDB Publications. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organization. 2024. Global Youth Employment Trends 2024. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/es/publications/major-publications/tendencias-mundiales-del-empleo-juvenil-2024 (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Jordan, Ramiro, Kamil Agi, Sanjeev Arora, Christos G. Christodoulou, Edl Schamiloglu, Donna Koechner, Andrew Schuler, Kerry Howe, Ali Bidram, Manel Martinez-Ramon, and et al. 2021. Peace engineering in practice: A case study at the University of New Mexico. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 173: 121113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantis, Hugo D., Juan S. Federico, and Sabrina Ibarra García. 2020. Entrepreneurship policy and systemic conditions: Evidence-based implications and recommendations for emerging countries. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences 72: 100872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplinsky, Raphael, and Erika Kraemer-Mbula. 2022. Innovation and uneven development: The challenge for low- and middle-income economies. Research Policy 51: 104394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, Mathew J., Punya Mishra, and William Cain. 2024. What Is Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK)? Journal of Education 193: 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, Sascha, Carolin Palmer, Norbert Kailer, Friedrich Lukas Kallinger, and Jonathan Spitzer. 2019. Digital entrepreneurship: A research agenda on new business models for the twenty-first century. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research 25: 353–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landuci, Felipe Schwahofer, Marina Fernandes Bez, Paula Dugarte Ritter, Sandro Costa, Fausto Silvestri, Guilherme Burigo Zanette, Beatriz Castelar, and Paulo Márcio Santos Costa. 2021. Mariculture in a densely urbanized portion of the Brazilian coast: Current diagnosis and directions for sustainable development. Ocean & Coastal Management 213: 105889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larios-Francia, Rosa Patricia, and Marcos Ferasso. 2023. The relationship between innovation and performance in MSMEs: The case of the wearing apparel sector in emerging countries. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 9: 100018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Liang, Fang Su, Wei Zhang, and Ji-Ye Mao. 2021. Digital transformation by SME entrepreneurs: A capability perspective. Information Systems Journal 28: 1129–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, Ritika, and Kaushik Ranjan Bandyopadhyay. 2021. Women entrepreneurship and sustainable development: Select case studies from the sustainable energy sector. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy 15: 42–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, Stephan, and Stanislav Vavilov. 2023. Global development agenda meets local opportunities: The rise of development-focused entrepreneurship support. Research Policy 52: 104795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Gregorio, Sara, Laura Badenes-Ribera, and Anita Oliver. 2021. Effect of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurship intention and related outcomes in educational contexts: A meta-analysis. The International Journal of Management Education 19: 100545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Maturano, Janet, Julien Bucher, and Stijn Speelman. 2020. Understanding and evaluating the sustainability of frugal water innovations in México: An exploratory case study. Journal of Cleaner Production 274: 122692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrar, Rabeh, and Sofiane Baba. 2022. Social innovation in extreme institutional contexts: The case of Palestine. Management Decision 60: 1387–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouloudj, Kamel, Elif Habip, and Hadda Rebbouh. 2024. Investigating Digital Entrepreneurial Intentions: An Extended Technology Acceptance Model. In Digitizing Green Entrepreneurship. Hershey: IGI Global Scientific Publishing, pp. 71–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, William, Carla Garcia-Lozano, Diego Varga, and Josep Pintó. 2024. Analysis of recent land management initiatives in Nicaragua from the perspective of the “ecosystem approach”. Journal of Environmental Management 354: 120285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, Jochem Wilfried. 2021. Education and inspirational intuition—Drivers of innovation. Heliyon 7: e07923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambisan, Satish, Donald Siegel, and Martin Kenney. 2018. On open innovation, platforms, and entrepreneurship. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 12: 354–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambisan, Satish, Mike Wright, and Maryann Feldman. 2019. The digital transformation of innovation and entrepreneurship: Progress, challenges and key themes. Research Policy 48: 103773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, Alexander, Martin Obschonka, Susan Schwarz, Michael Cohen, and Ingrid Nielsen. 2019. Entrepreneurial self-efficacy: A systematic review of the literature on its theoretical foundations, measurement, antecedents, and outcomes, and an agenda for future research. Journal of Vocational Behavior 110: 403–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Chávez, Miguel Angel, José Enrique Mendoza-Pumapillo, Josue Otoniel Dilas-Jiménez, and Carlos Andrés Mugruza-Vassallo. 2024. E-commerce of Peruvian SMEs: Determinants of internet sales before and during COVID-19. Heliyon 10: e40331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osorno-Hinojosa, Roberto, Mikko Koria, Delia del Carmen Ramírez-Vázquez, and Gabriela Calvario. 2023. Designing Platforms for Micro and Small Enterprises in Emerging Economies: Sharing Value through Open Innovation. Sustainability 15: 11460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, Matthew J., Joanne E. McKenzie, Patrick M. Bossuyt, Isabelle Boutron, Tammy C. Hoffmann, Cynthia D. Mulrow, Larissa Shamseer, Jennifer M. Tetzlaff, Elie A. Akl, Sue E. Brennan, and et al. 2021. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372: n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paidicán, Miguel, and Pamela Arredondo. 2024. La inteligencia artificial en contextos del conocimiento técnico pedagógico del contenido (TPACK): Una revisión bibliográfica. Panorama 18: 54–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, Justin, Ibrahim Alhassan, Nasser Binsaif, and Prakash Singh. 2023. Digital entrepreneurship research: A systematic review. Journal of Business Research 156: 113507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, Il-haam, and Glenda Kruss. 2021. Universities as change agents in resource-poor local settings: An empirically grounded typology of engagement models. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 167: 120693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, Amy, Rosalie Luo, and Joel Wendland-Liu. 2024. Shifting the paradigm: A critical review of social innovation literature. International Journal of Innovation Studies 8: 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranckutė, Raminta. 2021. Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus: The Titans of Bibliographic Information in Today’s Academic World. Publications 9: 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkhowa, Pallavi, and Heike Baumüller. 2024. Assessing the potential of ICT to increase land and labour productivity in agriculture: Global and regional perspectives. Journal of Agricultural Economics 75: 329–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Solís, Edgar Rogelio, Maria Fonseca, Fernando Sandoval-Arzaga, and Ernesto Amoros. 2021. Survival mode: How Latin American family firms are coping with the pandemic. Management Research: The Journal of the Iberoamerican Academy of Management 19: 259–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratten, Vanessa. 2021. COVID-19 and entrepreneurship: Future research directions. Strategic Change 30: 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, Thomas, and Carsten Lund Pedersen. 2020. Digitization Capability and the Digitalization of Business Models in Business-to-business Firms: Past, Present, and Future. Industrial Marketing Management 86: 180–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Rivero, Rocío, Isabel Ortiz-Marcos, Virginia Díaz-Barcos, and Sergio Andrés Lozano. 2020. Applying the strategic prospective approach to project management in a development project in Colombia. International Journal of Project Management 38: 534–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahut, Jean-Michel, Luca Iandoli, and Frédéric Teulon. 2021. The age of digital entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics 56: 1159–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, José, Alexander Ward, Brizeida Hernández, and Jenny Lizette Florez. 2017. Educación emprendedora: Estado del arte. Propósitos y Representaciones 5: 401–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, Ushasi, Himadri Sikhar Pramanik, Sayantan Datta, Swayambhu Dutta, Sankhanilam Dasgupta, and Manish Kirtania. 2023. Assessing sustainability focus across global banks. Development Engineering 8: 100114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolov, Maxim, Dmitry Marushko, Leonid Zhigun, Ivan Morozov, and Meir Surilov. 2021. Youth innovative entrepreneurship under digitalization of economics: Analysis of foreign experience in assessing the effectiveness of support. Economic Annals-XXI 193: 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spigel, Ben. 2020. Entrepreneurial Ecosystems: Theory, Practice, Futures. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susila, Ihwan, Dianne Dean, Kun Harismah, Kuswaji Dwi Priyono, Anton Agus Setyawan, and Huda Maulana. 2024. Does interconnectivity matter? An integration model of agro-tourism development. Asia Pacific Management Review 29: 104–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toscher, Ben, Yngve Dahle, and Martin Steinert. 2020. Get Give Make Live: An empirical comparative study of motivations for technology, youth and arts entrepreneurship. Social Enterprise Journal 16: 179–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullman, Amanda N., and Noah Kittner. 2024. Are global efforts coordinated for a Just Transition? A review of civil society, financial, government, and academic Just Transition frameworks. Energy Research & Social Science 108: 103371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO]. 2024. Global Education Monitoring Report 2023: Technology in Education: A Tool on Whose Terms? Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000388894 (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Valdez-Juárez, Luis Enrique, and Domingo García Pérez-de-Lema. 2023. Creativity and the family environment, facilitators of self-efficacy for entrepreneurial intentions in university students: Case ITSON Mexico. The International Journal of Management Education 21: 100764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eck, Nees Jan, and Ludo Waltman. 2017. Citation-based clustering of publications using CitNetExplorer and VOSviewer. Scientometrics 111: 1053–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas, Elkin, and Mariana Flores-García. 2023. Chapter 1—Urbanization in the context of global environmental change. In Urban Climate Adaptation and Mitigation. Edited by Ayyoob Sharifi and Amir Reza Khavarian-Garmsir. Amsterdam: Elsevier, pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, Viswanath, James Y. L. Thong, and Xin Xu. 2022. Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology: A Synthesis and the Road Ahead. Social Science Research Network, SSRN Scholarly Paper No. 2800121. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2800121 (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Vos, Rob, and Andrea Cattaneo. 2021. Poverty reduction through the development of inclusive food value chains. Journal of Integrative Agriculture 20: 964–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, Danielle, Minoo Rathnasabapathy, Keith Javier Stober, and Pranav Menon. 2024. Challenges and progress in applying space technology in support of the sustainable development goals. Acta Astronautica 219: 678–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, Shaker A., Wan Liu, and Steven Si. 2023. How digital technology promotes entrepreneurship in ecosystems. Technovation 119: 102457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Jianhong, Désirée van Gorp, and Henk Kievit. 2023. Digital technology and national entrepreneurship: An ecosystem perspective. The Journal of Technology Transfer 48: 1077–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Yin, and Bin Deng. 2024. Exploring the nexus of smart technologies and sustainable ecotourism: A systematic review. Heliyon 10: e31996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Quality Criteria | Studies That Comply | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Clearly described methodology | 68/74 | 92% |

| Appropriate target population | 74/74 | 100% |

| Reported effectiveness measures | 61/74 | 82% |

| Recognized limitations | 45/74 | 61% |

| Author(s) and Year | Country or Region | Journal/Database | Type of Study/Methodology | Digital Technology Studied | Population/Sample | Main Findings—Youth Entrepreneurship | Theoretical Connexion | SDG Link | Robustness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ferrante et al. (2024) | Learning, Media, and Technology | Comparative policy study | Digital technologies, ICT | Education policies | Digital education policies address inequalities through contextualized socio-technical imaginaries | Sociotechnical theory | SDG 4 | High | |

| 2 | Ancheta-Arrabal et al. (2021) | Argentina, Mexico | Education Sciences | Systematic review Literature | ICT (Information and Communication) | Women in ICT education | The gender digital divide affects educational equity in Latin American countries, limiting female entrepreneurship | Gender digital divide theory | SDG 4, SDG 5 | Environment |

| 3 | Burgos and Branch (2021) | Latin America | Lecture Notes Educational Technology | Multiple cases | AI, Technology 4.0, e-learning | Universities | Digital transformation required to upgrade universities with AI and Technology 4.0 to train entrepreneurs | Digital transformation theory | SDG 4, SDG 9 | High |

| 4 | Sánchez et al. (2017) | Latin America (Mexico, Peru, Colombia, Chile, Ecuador, Bolivia, Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay) | Journal of Educational Psychology | Review 108 sources | Educational technology Entrepreneurship | University students | Entrepreneurial education contributes to business creation, but Latin America needs to make extra efforts in its curricula | Entrepreneurial behaviour theory | SDG 4, SDG 8 | High |

| 5 | Ortiz-Chávez et al. (2024) | Latin America | Heliyon | Two-stage Heckman model | E-commerce, ICT | Peruvian SMEs | Digital readiness is crucial for adopting online sales, but not for scaling up during the pandemic | Technology adoption theory | SDG 8, SDG 9 | High |

| 6 | Ramírez-Solís et al. (2021) | Peru | Management Research | Survey of 194 family businesses | Business survival technologies | Family businesses | Family businesses survive through family entrepreneurship, protecting their wealth during COVID-19 | Theory of family entrepreneurship | SDG 8 | High |

| 7 | Azevedo et al. (2020) | Latin America (Mexico, Colombia, Venezuela, Peru, Chile) | Journal of Business Research | Qualitative 25 leaders | Technologies social rebalancing | Progressive leaders | Progressive leaders propose technological solutions to advance toward a better future for the region | Mintzberg’s social rebalancing theory | SDG 10 | Environment |

| 8 | Kantis et al. (2020) | Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Uruguay | Socio-Economic Planning Sciences | Analysis of IDE index evidence | Digital ecosystems Entrepreneurship | Young entrepreneurs, startups | Emerging countries need contextualized entrepreneurship policies that take into account specific structural factors. | Entrepreneurial ecosystems theory | SDG 8, SDG 9 | High |

| 9 | Castro-Spila et al. (2018) | Emerging countries (including Latin America) | Higher Education Skills Work-Learning | Agile research prototypes | Social innovation lab tourism | University students | SISTOUR-LAB enables mapping of tourism vulnerabilities and experimental training in social innovation prototypes | Work-based learning theory | SDG 4, SDG 8 | Environment |

| 10 | Larios-Francia and Ferasso (2023) | Latin America (sustainable tourism) | Journal Open Innovation | PLS-SEM 104 Textile SMEs | Innovation in product and process | Micro, small, and medium enterprises | Product innovation with process innovation explained 47.1% of organizational performance in the textile sector | Business innovation theory | SDG 8, SDG 9 | High |

| 11 | Rodríguez-Rivero et al. (2020) | Peru, Colombia | Int. Journal Project Management | Prospective approach case study | Higher technical education model | Low-income youth | Despite regional circumstances, future problems were identified in advance with a positive impact | Strategic forward-looking approach | SDG 4, SDG 8 | High |

| 12 | Arbeláez-Rendón et al. (2023) | Colombia | Journal Open Innovation | Dynamics systems survey ICT | ICT, digital economy, gap | ICT sector entrepreneurs | The creation of digital ventures as an alternative to ICT jobs, but the lack of qualified individuals inhibits growth, | Digital divide theory | SDG 8, SDG 9 | High |

| 13 | Valdez-Juárez and García Pérez-de-Lema (2023) | Colombia | Int. Journal Management Education | PLS-SEM 868 students | Educational technologies creativity | Undergraduate university students | Creativity has positive effects on self-efficacy and entrepreneurial intentions. The family business environment affects self-efficacy | Theory of planned behaviour | SDG 4, SDG 8 | High |

| 14 | Gonzalez-Tamayo et al. (2024) | Mexico (Sonora State) | Int. Journal Management Education | SEM 9703 entrepreneurial students | UTAUT entrepreneurial behaviour | Students with businesses | Founder intentions for success and environmental conditions significantly impact entrepreneurial success actions | UTAUT theory | SDG 8, SDG 9 | High |

| 15 | Bravo-Ortega et al. (2023) | Europe and Latin America | Economic Analysis and Policy | Machine learning quantum regressions | Technology Productivity Growth | MSMEs | SMEs run by experienced managers with educated employees exhibit higher productivity | Human capital theory | SDG 8, SDG 9 | High |

| 16 | Muñoz et al. (2024) | Middle-income economy (Latin American context) | Journal of Environmental Management | Multivariate analysis Principles Malawi | LUMI land use management | 455 small farmers | LUMI incorporates the principles of 1–5 Malawi. Three farm clusters: active management, moderate management, room for improvement | Malawi management principles | SDG 2, SDG 15 | High |

| 17 | Landuci et al. (2021) | Nicaragua | Ocean & Coastal Management | Survey 20 mariculturists interviewed | Sustainable mariculture technologies | Mariculture producers | Transition towards greater control of production methods and diversification of species. Requires digitisation | Sustainable development theory | SDG 14, SDG 8 | Environment |

| 18 | Del Giudice et al. (2019) | Brazil | Tech. Forecasting Social Change | Quantitative analysis 142 entrepreneurs | Social innovation technologies | Social entrepreneurs | Technological innovation affected by social entrepreneurship, but insufficiently supportive entrepreneurial ecosystem | Social entrepreneurship theory | SDG 8, SDG 9 | High |

| 19 | Allal-Chérif et al. (2024) | Emerging countries (includes Latin America) | Journal of Business Research | Multiple cases, 10 countries | Esports, video game technologies | Entrepreneurs in esports | Sustainable esports entrepreneurs put their knowledge in the service of society with boldness and ingenuity | Sustainable entrepreneurship theory | SDG 8, SDG 10 | High |

| 20 | Haji (2021) | Brazil, Argentina (emerging countries) | Journal of Integrative Agriculture | Systematic comparative analysis | E-commerce ICT rural areas | Remote rural population | Rapid development of e-commerce in BRICS countries, but problems of disproportionate development in regions and lack of cooperation | Inclusive development theory | SDG 1, SDG 9 | High |

| 21 | Molina-Maturano et al. (2020) | Brazil (BRICS)Mexico | Journal of Cleaner Production | Case questionnaire interviews | Frugal innovations water | Rural communities | Frugal innovations related to catalytic and social innovation. Positive impact in three dimensions of sustainability | Frugal innovation theory | SDG 6, SDG 11 | High |

| 22 | Morrar and Baba (2022) | Emerging context (applicable to Latin America) | Management Decision | Qualitative 24 interviews | Innovation in technologies social innovation | NGOs Social entrepreneurs | Three barriers: institutional, effectiveness, sustainability hinder social innovation Extreme institutional contexts | Innovation in institutional theory | SDG 16 | High |

| 23 | Susila et al. (2024) | Applicable context Latin America (agritourism) | Asia Pacific Management Review | Grounded theory 17 participants | Agrotourism management technologies | Civil servants, farmers, merchants | Community participation maintains the sustainability of agrotourism through marketing innovations and entrepreneurship | Grounded theory | SDG 8, SDG 11 | Environment |

| 24 | Arslan et al. (2021) | Applicable context (Latin American pyramid base) | Journal Small Business Enterprise Development | Qualitative in-depth interviews | Fintech, mobile money | Pyramid base entrepreneurs | Fintech reduces uncertainty in business operations and offers growth opportunities for entrepreneurs at the base of the pyramid | Bottom of the pyramid entrepreneurship theory | SDG 8, SDG 1 | High |

| 25 | Sengupta et al. (2023) | Global context (includes Latin American banks) | Development Engineering | Content analysis of 50 banks | Smart technologies Sustainability | Banking sector | Banks play a direct intermediary role in achieving the SDGs. Motivations vary between core business objectives and corporate citizenship | Sustainable development theory | All SDGs | High |

| 26 | Mahajan and Bandyopadhyay (2021) | Global context (including Latin American cases) | Journal Enterprising Communities | Multiple cases 8 companies | Smart ecotourism technologies | Female entrepreneurs in the energy sector | Women’s entrepreneurship advances sustainable development through clean technologies and innovative business models | Theory of female entrepreneurship | SDG 5, SDG 7 | Environment |

| 27 | Adams et al. (2018) | Decolonial context (relevant to Latin America) | Int. Journal of Intercultural Relations | Decolonial Theory analysis | Technologies of modernity/coloniality | Global South communities | Decolonial approaches consider modernity in terms of inherent coloniality, affecting technological development | Decolonial theory | SDG 10, SDG 16 | Environment |

| 28 | Zhang and Deng (2024) | Global context | Heliyon | PRISMA systematic review | Smart technologies ecotourism | Multiple stakeholders | Smart technologies such as IoT are crucial for sustainable tourism management. Collaboration between governments, communities, and organizations | Sustainable tourism theory | SDG 8, SDG 11 | High |

| 29 | Ullman and Kittner (2024) | (applicable to Latin America) | Energy Research & Social Science | Review 75 documents | Transition technologies only. | Multiple stakeholders | Transition frameworks vary greatly in scope and design. Expanded literature on Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa | Just transition theory | Multiple SDGs | High |

| 30 | Jordan et al. (2021) | Global context (emphasis on Latin America, sub-Saharan Africa) | Tech. Forecasting Social Change | Case study University of New Mexico | Peace engineering technologies | Engineering students | Peace engineering activities include telemedicine, sustainable water resources, microgrids, and smart cities | Peace engineering theory | Multiple SDGs | High |

| 31 | Petersen and Kruss (2021) | United States (model applicable to Latin America) | Tech. Forecasting Social Change | Township case studies | Technology university participation | Resource-poor local communities | Four types of university participation models to catalyze social change in resource-poor environments | Agency theory of change | SDG 4, SDG 10 | High |

| 32 | Andonova and García (2018) | South Africa (model applicable to Latin America) | Transnational Corporations Review | Study of 11 Colombian multinationals | Peacebuilding technologies | Emerging multinationals | Colombian multinationals launch limited peacebuilding initiatives following the 2016 peace agreement | Peacebuilding theory | SDG 16 | Environment |

| 33 | Manning and Vavilov (2023) | Colombia | Research Policy | Rich qualitative data | Support for entrepreneurial development | Impact entrepreneurs | Personalized entrepreneurship support provided by Global North development organizations to Global South entrepreneurs | Theory of chains of development assistance | SDG 8, SDG 17 | High |

| 34 | Phillips et al. (2024) | Rwanda, Uganda (model applicable to Latin America) | Int. Journal Innovation Studies | Critical review 10 years | Social innovation paradigms | Multiple stakeholders | Three social innovation paradigms: instrumentalist, strong, democratic. Geographical diversity more likely in the democratic paradigm | Theory of social innovation paradigms | Multiple SDGs | High |

| 35 | Kaplinsky and Kraemer-Mbula (2022) | Global context (critical perspective applicable to Latin America) | Research Policy | Theoretical essay paradigms | Development of ICT innovation | Emerging economies | ICTs offer transformative opportunities for low- and middle-income countries through the informal sector and South-South trade | Theory of Techno-economic paradigms | SDG 8, SDG 9 | High |

| 36 | Frimpong (2024) | Global context (emphasis on low and middle-income economies ) | World Development Perspectives | Dynamic panel 121 countries | Innovation stability in technologies | Multiple countries | Innovation negatively affects political stability, especially in countries with high innovation output. 48% reduction in stability | Innovation-Stability Theory | SDG 16 | High |

| 37 | Vargas and Flores-García (2023) | Global context (121 countries, including Latin America) | Urban Climate Adaptation | Review of urbanization and climate change | Smart city technologies | Urban population | 68% of the world’s population will live in urban areas by 2050. Need for disruptive smart solutions for climate change | Sustainable urbanization theory | SDG 11, SDG 13 | Environment |

| 38 | Alves et al. (2024) | Global urban context (applicable to Latin American cities) | Environmental Science & Policy | DEA analysis 70 engineering classes | Active educational technologies | Engineering students | Active learning classes are more efficient than passive ones. Efficient classes concentrated in recent years before graduation | Active learning theory | SDG 4, SDG 8, SDG 10 | High |

| 39 | Brixiová et al. (2020) | South America | Economic Modelling | Analysis of female entrepreneurship | Training technologies | African women entrepreneurs | Financial literacy training directly benefits men, but does not increase sales levels for women entrepreneurs | Theory of Female Entrepreneurship | SDG 5, SDG 8 | High |

| 40 | Wood et al. (2024) | Africa (model applicable to Latin America) | Acta Astronautica | Space technology analysis | Space technologies SDGs | Multiple stakeholders | Six space technologies applied to advance the SDGs: Earth observation, communications, navigation, and microgravity research | Space technology development theory | Multiple SDGs | High |

| 41 | Rajkhowa and Baumüller (2024) | Global context (applicable to Latin America) | Journal of Agricultural Economics | Panel analysis 86 countries | ICT agricultural productivity | Multiple countries | ICT penetration contributes to agricultural productivity, but effects vary by regional infrastructure and human capital | ICT development theory | SDG 1, SDG 2 | High Environment |

| 42 | Müller (2021) | Nigeria | Heliyon | Theoretical analysis of education and innovation | Inspirational intuition education | Education systems | Education generates knowledge throughout life. Inspirational intuition plays an important role as a driver of innovation | Education-innovation theory | SDG 4 | Environment |

| 43 | Dzator et al. (2023) | (model applicable to Latin America) | Telecommunications Policy | Panel 44 countries 2010–2019 | ICT poverty reduction | 44 developed countries | ICT penetration contributes to poverty reduction, but the effects vary depending on the prior socioeconomic context | ICT development theory | SDG 1, SDG 9 | High |

| 44 | Vos and Cattaneo (2021) | Global context (applicable to Latin America) | Journal Integrative Agriculture | Analysis of food value chains | ICT food value chains | Small and medium-sized enterprises | Food markets create employment and income opportunities throughout supply chains, reducing poverty | Theory of inclusive value chains | SDG 1, SDG 2 | High |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Silva León, P.M.; Cruz Salinas, L.E.; Farfán Chilicaus, G.C.; Castro Ijiri, G.L.; Chuquitucto Cotrina, L.K.; Heredia Llatas, F.D.; Ramos Farroñán, E.V.; Pérez Nájera, C. Digital Technologies for Young Entrepreneurs in Latin America: A Systematic Review of Educational Innovations (2018–2024). Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 537. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14090537

Silva León PM, Cruz Salinas LE, Farfán Chilicaus GC, Castro Ijiri GL, Chuquitucto Cotrina LK, Heredia Llatas FD, Ramos Farroñán EV, Pérez Nájera C. Digital Technologies for Young Entrepreneurs in Latin America: A Systematic Review of Educational Innovations (2018–2024). Social Sciences. 2025; 14(9):537. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14090537

Chicago/Turabian StyleSilva León, Pedro Manuel, Luis Edgardo Cruz Salinas, Gary Christiam Farfán Chilicaus, Gabriela Lizeth Castro Ijiri, Lisseth Katherine Chuquitucto Cotrina, Flor Delicia Heredia Llatas, Emma Verónica Ramos Farroñán, and Celin Pérez Nájera. 2025. "Digital Technologies for Young Entrepreneurs in Latin America: A Systematic Review of Educational Innovations (2018–2024)" Social Sciences 14, no. 9: 537. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14090537

APA StyleSilva León, P. M., Cruz Salinas, L. E., Farfán Chilicaus, G. C., Castro Ijiri, G. L., Chuquitucto Cotrina, L. K., Heredia Llatas, F. D., Ramos Farroñán, E. V., & Pérez Nájera, C. (2025). Digital Technologies for Young Entrepreneurs in Latin America: A Systematic Review of Educational Innovations (2018–2024). Social Sciences, 14(9), 537. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14090537