Abstract

Discrimination and harassment (DH) against women are topics of broad concern to gender equality advocates. This study aimed to investigate the prevalence of DH against women in Nigeria, based on seven specific forms of DH captured in the 2021 Nigeria Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS), and to identify key socio-demographic factors associated with an aggregated DH outcome variable. Drawing upon data from 38,806 women aged 15–49, we used descriptive statistics to summarize the prevalence of DH across seven reasons and the socio-demographic characteristics of respondents, followed by chi-square analysis to test bivariate associations and binary logistic regression to identify predictors. Results showed that the prevalence of DH against Nigerian women (18.9%) was significantly associated with socio-demographic factors such as age, education level, wealth index, marital status, and ethnicity. At the individual level, women who felt very unhappy had higher odds of experiencing DH (OR = 3.101, 95% CI: 2.393–4.018, p < 0.001) compared to those who felt very happy. In contrast, women with higher/tertiary education (OR = 0.686, 95% CI: 0.560–0.842, p < 0.001) were 31.4% less likely to face DH than those with no education. Regionally, respondents living in Zamfara (OR = 5.045, 95% CI: 3.072–8.288, p < 0.001) were over five times more likely to experience DH than those in Kano state. The findings underscore the need for policy interventions and support systems to address DH against women in Nigeria.

1. Introduction

“Being born and growing up as a girl in a developing society like Nigeria is almost like a curse due to contempt and ignominy treatment received from the family, the school and the society at large”(Alabi et al. 2014, p. 393).

Nigeria, Africa’s largest economy and most populous country, is home to more than 250 ethnic groups and 500 languages that shape its sociopolitical structures (Soroosh et al. 2015). Long before the establishment of the modern Nigerian state, the region was inhabited by diverse Indigenous communities who engaged in extensive intergroup interactions shaped by regional and trans-Saharan trade networks (Heaton 2024; Nnama-Okechukwu and McLaughlin 2023). However, British colonial rule in the 19th century disrupted these systems. In 1914, the British forcibly amalgamated three distinct regions—the Northern Protectorate, the Southern Protectorate, and the Colony of Lagos—into a single political entity, laying the groundwork for enduring institutional hierarchies (Soroosh et al. 2015). Although Nigeria gained independence in 1960, the colonial legacy of Eurocentric governance structures, knowledge systems, and social norms constantly shapes contemporary society. These influences have perpetuated rigid gender roles and entrenched social inequalities that disadvantage women in Nigeria (Olonade et al. 2021).

In alignment with global commitments under Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) 5 and 10, governments worldwide have pursued gender equality through legislative reforms, gender-responsive policies, and educational initiatives (Maheshwari et al. 2025; Okongwu 2024). Despite these efforts, women continue to be victims of both overt and subtle discrimination and harassment (DH). Discrimination generally falls into two forms: direct and indirect (Alam et al. 2024; Owen 2024). Direct discrimination involves the intentional differential treatment of individuals based on their membership in socially salient groups (Owen 2024). In contrast, indirect discrimination arises when ostensibly neutral rules or practices disproportionately disadvantage individuals with protected characteristics, such as gender (Khanna 2024, p. 307). Harassment, defined as “unwanted, unwelcome or uninvited behaviour that makes a person feel humiliated, intimated or offended”(Huang et al. 2018, p. 3868), is prevalent in multiple spheres, such as education, science and sports, housing, public media, and employment (Devis-Devis et al. 2017). DH against women not only undermines their rights but also poses serious threats to their health and well-being. Evidence from both Nigeria and the US shows that discrimination against women in the workplace, such as being denied promotions, can lead to heightened psychological distress, including depression, anxiety, and psychosomatic symptoms (Hammond et al. 2010). In Indonesia, women subjected to sexual harassment often report symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, along with deteriorating mental and physical health (Darmayasa et al. 2023; Gianakos et al. 2022). Such impacts can severely limit women’s ability to play an active role in shaping their communities and contributing to broader societal development.

Recent global evidence highlights that discrimination against women is widespread, with race (38%), gender (33%), and ethnicity (20%) identified as the most commonly reported grounds (UNESCO 2025). It is important to note that high-income nations such as the United States and Hungary constantly reported high levels of discrimination, indicating that economic development alone is insufficient to eliminate entrenched discrimination. Harassment, a pervasive manifestation of gender-based discrimination, remains prevalent across both public and private settings. According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), 17.6% of women report having experienced psychological harassment in the workplace (Okongwu 2024). Several US studies highlight the need to address DH. For instance, Newman (2014) stressed prioritizing leadership and management practices that acknowledge diversity and protect women’s rights in health workplaces. Heilman and Caleo (2018) identified two strategies to combat DH: (1) challenging perceptions that women are unsuited for male-typed roles, and (2) preventing these perceptions from influencing evaluative judgments.

If we look into Nigeria, its low ranking on the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Index (118th out of 142 in 2014, with a disparity score of 0.639) highlights the severity of gender inequality nationally. Women in Nigeria face significant discrimination across various domains, particularly in political representation, economic participation, and educational attainment. Despite making up nearly half of the national population, women are significantly underrepresented in political leadership, holding only 6.7% of parliamentary seats in 2014 and 5.6% in 2015 (Bako and Syed 2018). Gender-based inequalities also persist in the labour market where women hold just 11% of formal sector jobs compared to 30% for men (Olonade et al. 2021). This disparity is further reflected in the agricultural sector, where women contribute up to 80% of total production—accounting for roughly 41% of the country’s GDP—yet control only 1% of farming assets due to gender discriminatory practices around land ownership (Bako and Syed 2018). Given the prevalence of a traditional masculine culture in Nigerian higher education institutions, only 10.4% of women receive higher education as of 2019 (Adeliyi et al. 2022; Bakari and Leach 2007).

Furthermore, sexual harassment is a significant issue for Nigerian women, particularly in academic and professional settings. Research by Bako and Syed (2018) found that 20–30% of female students at Nigerian universities experience sexual harassment from male staff and lecturers, with common forms including inappropriate comments, unwanted physical contact, and pressure for sexual favours in exchange for academic benefits. Despite formal complaints, little action is often taken to address these incidents, reflecting a lack of institutional response. Similarly, in the workplace, female junior employees frequently face sexual harassment from male supervisors (Yusuf 2010). Echoed in recent research in the Mexican context (Mesa-Chavez et al. 2025), many choose not to report the abuse due to fears of retaliation or job loss, thereby fostering a culture of silence that perpetuates the problem.

These DH phenomena are embedded in the complex interplay of religious ideologies, cultural norms, and legal systems. Customary and religious laws, rooted in Igbo tradition and Sharia law, reinforce patriarchal structures that legitimize DH (Bako and Syed 2018). Dominant religions like Christianity and Islam contribute to a culture of impunity of such practices through doctrines that promote female submission and gender segregation (Para-Mallam 2010). In many tribal and ethnic communities, women are subjected to genital mutilation, child marriage, and widowhood practices—through which they are treated as property to be inherited by male relatives. These forms of discrimination are often accompanied by harassment, both verbal and physical, which create hostile environments that endanger and marginalize women (Bako and Syed 2018).

Although the Nigeria has been a signatory to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) since 1985, the effectiveness of this legal protection is limited by the country’s dualist legal system which requires international treaties to be enacted into domestic law before they become enforceable (Udu et al. 2023). However, translating treaties such as CEDAW into domestic law is challenging in both Nigeria and internationally (e.g., the U.S, Canada, Kuwait) (George 2020; Lamarche 2013; Runyan and Sanders 2021), due to lengthy legislative processes, limited political will to prioritise gender equality over economic or security concerns, and perceptions that gender rights conflict with customary or religious law which takes precedence (Bazaanah and Ngcobo 2024; Wardhani and Natalis 2024). To preserve patriarchal privileges, government officials often dilute CEDAW principles or fail to “vernacularize” or “indigenize” the principles in a way that genuinely benefits women (Runyan and Sanders 2021). This legal gap perpetuates harmful traditional and religious practices, rendering women vulnerable to lifelong inequality and abuse.

An emerging body of gender studies has attempted to gain a greater understanding of DH against women worldwide (Rankine 2001; SteelFisher et al. 2019). In New Zealand, high rates of abuse and discrimination were reported among lesbian and bisexual women, with Māori participants disproportionately affected (Rankine 2001). However, the study’s small bisexual sample and limited theoretical framing hindered understanding of intersectional dynamics. In the United States, Walsh et al. (2022) linked racial discrimination to PTSD and depression among diverse female rape survivors, highlighting the intersection of sexual and racial trauma. Nevertheless, their focus on clinical outcomes overlooked broader institutional factors. Similarly, research in Mexico revealed persistent DH against women physicians during training and practice, yet did not examine how hierarchical medical cultures exacerbate these abuses (Mesa-Chavez et al. 2025). Studies from Australia (Morgan et al. 2025), Canada (Son Hing et al. 2023), UK (Manzi et al. 2024) further confirmed the pervasive nature of DH against women, underscoring the need to develop strategies that ensure safe academic and workplace environments for women.

Despite this attention, most studies focus on developed countries or specific professional settings, often neglecting broader population-level patterns in developing countries. Although some studies have examined women’s attitudes and coping strategies in relation to DH (Aborisade 2022; Okongwu 2024), few studies have systematically analyzed how socio-demographic characteristics shape women’s exposure to DH. Seeking to address these gaps, this study examined the prevalence of DH against women in Nigeria, utilizing seven distinct DH indicators from the 2021 Nigeria Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS), and investigated key socio-demographic factors associated with a composite DH outcome variable. In doing so, it provides novel insights into population-level patterns of gender-based discrimination in a developing country, complementing research largely conducted in Western contexts.

Nigeria’s large and diverse population, together with its rich cultural and religious traditions and significant regional economic influence, makes it a particularly important context for investigating DH against women. Limited enforcement of protective legal frameworks, coupled with growing awareness and mobilisation among women, underscores the need to examine how socio-demographic factors influence vulnerabilities to DH. This study seeks to contribute to a more nuanced understanding of DH against women in Nigeria, with findings that may have global relevance by informing scholars, policymakers, and practitioners worldwide. Specifically, the results can guide evidence-based policies and interventions to reduce DH nationally and internationally, while supporting gender-equality initiatives that foster inclusive, fair social environments, ensure equal access to opportunities, and advance equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) policies. In doing so, this work may also contribute to the achievement of SDGs related to gender equality and human rights.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

Data were obtained from the sixth round of the 2021 Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) conducted in Nigeria. The MICS is designed to produce statistically robust and internationally comparable data on key indicators pertaining to education, health, and the protection of children and women, while also serving as a key tool for monitoring the progress toward the SDGs and for strengthening national statistical capacity. The survey was implemented by the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) of Nigeria, with technical assistance from UNICEF and financial support from the government and international partners. The survey findings and datasets are publicly available on the official UNICEF website (https://mics.unicef.org/surveys, accessed on 22 April 2025).

The MICS sample was designed to generate estimates for various indicators regarding the situation of children and women at the national level, across urban/rural areas, by state (including the FCT), and by geo-political zone in Nigeria. A two-stage probability sampling design was employed. In the first stage, a specific number of 1850 census enumeration areas were systematically selected within each stratum using probability proportional to size, followed by a household listing operation within each selected area. In the second stage, a systematic random sample of 20 households was selected from each enumeration area. Notably, some areas, particularly in Borno State, were excluded from the data collection process because of security concerns. For this study, the final analytic sample included 38,806 women aged 15–49 after eliminating cases with “Missing values,” “No responses” and “DK” (Don’t know).

Although the MICS survey employed five types of questionnaires, this study specifically draws on data from the household questionnaire (basic demographic information) and the women’s questionnaire (administered to all women aged 15–49 in each household). Data were collected using Computer-Assisted Personal Interviewing (CAPI) on tablets, supported by the Census and Survey Processing System software (CSPro, Version 6.3; U.S. Census Bureau and ICF International, Washington, DC, USA, 2013). Data quality was ensured through re-interviews, daily supervision, and regular review visits by management and external monitors.

2.2. Outcome Variables

The outcome variable was discrimination and harassment (DH) experienced by women aged 15–49 in the past 12 months in Nigeria. The 2021 MICS survey broadly defined DH against women as gender-based behaviors that disadvantage women, including unfair treatment, exclusion, bullying, or harassment in daily life (National Bureau of Statistics, Statistician General of the Federation, and Unicef 2021). The survey asked women seven distinct binary (yes/no) questions about whether they had personally experienced DH on the basis of: (1) ethnic or immigration origin; (2) gender identity; (3) sexual orientation; (4) age; (5) religion or belief; (6) disability; or (7) any unspecified reason. For this study, responses were aggregated to construct a binary outcome variable where coded “yes” if the respondent answered “yes” to any of the seven questions, indicating they experienced at least one form of discrimination or harassment in the past 12 months and coded “no” if the respondent answered “no” to all questions, indicating no experience of DH. This aggregation approach enabled the analysis of overall DH prevalence, regardless of the specific reason for the experience.

2.3. Independent Variables

A set of covariates related to women’s feelings of DH were considered for analysis. All selected covariates are classified into individual-level factors and community-level factors. At the individual level, this study considered women’s age, which was recorded to have three categories (in years) (15–24, 25–34, 35–49). Women’s education had five categories (none, primary, junior secondary, senior secondary, higher/tertiary). The study also categorized respondents into five socioeconomic collectives according to their wealth status: poorest, second, middle, fourth, and richest. Marital status was also divided into three categories (currently, formerly, and never married). They were also placed in one of nine ethnicity categories: Hausa, Igbo, Fulani, Kanuri, Ijaw, Tiv, Ibibio, Edo, and other ethnicity. The variable “feeling safe at home alone after dark” had five categories (very safe, safe, unsafe, very unsafe, never alone after dark). Both “ever circumcised” and “ability to get pregnant” were treated as separate binary variables coded as “yes” or “no.” Respondents were classified into five groups based on happiness extent: very happy, somewhat happy, neither happy nor unhappy, somewhat unhappy, and very unhappy. In this study, a community was defined as a census enumeration cluster or block. To account for community characteristics, the place of residence (urban or rural) was added as a proxy measure. The region variable was also considered by including 36 states and the FCT in the analysis.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

In this study, we used descriptive statistics to show the prevalence of DH for any of seven reasons and portray the overview of participants’ socio-demographic characteristics, which were presented as counts and percentages. We utilized the chi-square test to ascertain the differences in DH and sociodemographic characteristics among women. Furthermore, a binary logistic regression model was employed to examine the association between outcome and exposure variables. The results were reported in the form of odds ratios (OR), along with their respective 95% confidence intervals (CI). Statistical significance for the relationship between various factors and the likelihood of ever having experienced DH was defined as p < 0.05. All analyses were conducted using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 28, including both descriptive and inferential methods.

2.5. Ethics

This study utilizes de-identified data obtained from the Nigerian MICS. The survey protocol was approved by the National Steering Committee and a Review Committee constituted from the Technical Committee in August 2021, as part of the ethics process for the 2021 MICS. Prior to data collection, all participants gave informed consent, and for minors (15–17), both parental approval and their own assent were obtained. Confidentiality of all data was maintained through measures established during the original survey. Given that this study is based on secondary data, ethical clearance is therefore not required.

2.6. Strengths and Limitations

This study has a number of strengths and certain limitations. One of the advantages of this study is its use of the MICS, which offers a large sample size and nationally representative data, thereby ensuring that the findings can be both replicable and generalizable across Nigeria. Another strength is the comprehensive use of advanced statistical methods, incorporating covariates at both the individual and community levels, which enhances the robustness of the findings and reinforces their relevance for national-level policy and program development. The open-access nature of MICS data further promotes transparency, reproducibility, and the possibility of secondary analyses, making it a valuable resource for evidence-based policy formulation and future research on women’s health, rights, and social outcomes.

The study also engendered certain limitations which must be acknowledged. Methodologically, the cross-sectional design of the MICS prevents the establishment of causal relationships between variables and observed outcomes. Moreover, the 2021 MICS data may be subject to recall bias. Since the data only measured DH experiences among women in the past 12 months, this study could not capture lifetime or cumulative experiences of DH. Another notable limitation concerns missing values arising from the survey design. Variables such as “ever circumcised” or “able to get pregnant” were collected only from relevant subgroups (e.g., adult women or women of reproductive age), resulting in missing responses for inapplicable participants (e.g., women aged 15–17). This missingness, classified as Missing Completely at Random (MCAR), does not bias estimates but reduces the effective sample size for these analyses (Kang 2013). Additionally, important factors relative to occupational characteristics, media exposure, community networks, and nutrition and health status were not accounted for in our analysis, which may result in an incomplete understanding of the determinants of DH.

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence and Sociodemographic Reasons for Discrimination and Harassment

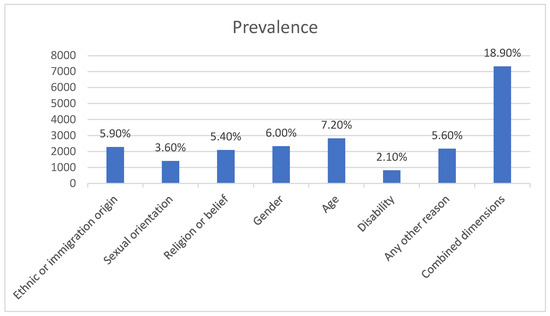

A total of 38,806 women aged 15–49 years who responded to the DH module in the survey were included in the analysis. Overall, 18.90% of respondents experienced DH due to at least one of the seven reasons in the past 12 months (Figure 1). Age appeared to be the most common reason (7.20%), followed by gender (6.00%) and ethnic or immigration origin (5.90%). Additionally, 5.40% of women reported DH based on religion or belief, while 5.60% attributed such incidents to reasons not specified in the listed categories. Comparatively lower proportions were observed for sexual orientation (3.60%) and disability (2.10%).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of discrimination or harassment that women aged 15–49 years felt across various dimensions in Nigeria, 2021 [n (%)].

3.2. Sociodemographic and Health-Related Characteristics of Women

Table 1 presents the background characteristics of the respondents. The majority of women were aged between 15 and 24 years (38.2%), with relatively smaller proportions in the 25–34 (29.0%) and 35–49 (32.8%) age groups. Approximately two-thirds of the women (59.8%) had completed secondary and higher/tertiary education, yet 26.6% lacked formal schooling. A relatively balanced distribution was observed across the wealth index quintiles, though a slightly higher proportion of respondents fell into the fourth (21.4%) and richest (22.7%) categories. In terms of marital/union status, the percentage of women who were currently married or in union (61.7%) was nearly twice as high as that of their never married counterparts (32.9%). Ethnically, women identifying as Hausa accounted for the largest percentage (25.5%), followed by Igbo (15.5%) and Fulani (6.5%). Regarding perceptions of personal safety, over half (50.6%) of women reported feeling safe when alone at home after dark, while 18.9% expressed feeling unsafe or very unsafe. With respect to reproductive health, 15.1% of respondents had undergone female circumcision, while the majority (59.4%) indicated they were able to get pregnant. Subjective happiness was high among respondents, with 42.4% feeling “very happy” and 36.6% considering themselves “somewhat happy”. At the community level, the sample was slightly skewed toward rural residents (54.1%) and represented all 37 regions with particularly large proportions drawn from Lagos (7.3%), Kano (6.7%), Katsina (4.1%), and Kaduna (4.0%).

Table 1.

Background characteristics of the respondents in Nigeria, 2021 [n (%)].

3.3. Chi-Square Analysis of Sociodemographic Characteristics of Discrimination and Harassment

Table 2 reveals statistically significant associations (p < 0.001 for most variables) between diverse sociodemographic factors and DH experienced by Nigerian women. These factors include individual-level characteristics such as age, education level, marital status, ethnicity, wealth quintile, circumcision status, perceptions of personal safety, and self-reported happiness. Furthermore, factors at the community level, such as residential setting and geographic region, also showed significant associations with DH against women.

Table 2.

Chi-square analysis between the socio-demographic characteristics and the prevalence of discrimination and harassment against women [n (%)].

It was observed that prevalence of DH declined with women’s increasing age. Women aged 15–24 (20.0%) experienced more DH than those aged 35–49 (17.2%). Women with no formal education (21.3%) encountered a higher prevalence compared to those who completed higher or tertiary education (16.5%). A clear wealth gradient was also observed, with women from the second poorest household (21.5%) more likely to experience DH than the rich (15.8%). In this study, a high prevalence of DH was also observed among formerly married women (20.9%), Edo women (31.9%), uncircumcised women (20.2%), and those unable to get pregnant (20.3%).

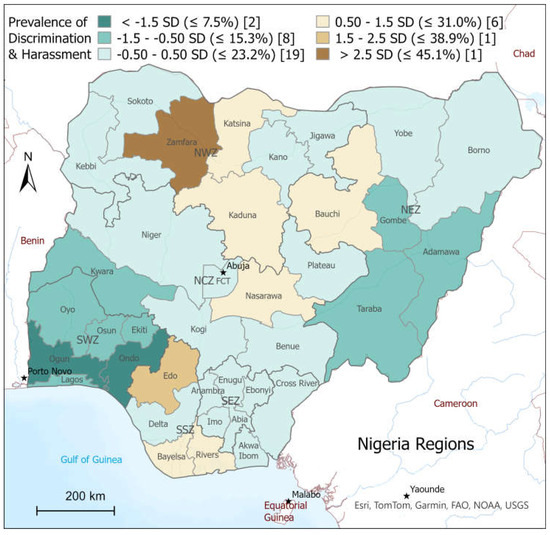

Perceptions of personal safety were strongly associated with the risk of experiencing DH. Women who felt very unsafe at home after dark reported the highest prevalence (43.0%), nearly three times higher than those who felt very safe (15.3%). Similarly, self-reported happiness showed an inverse relationship, with prevalence increasing from 15.2% among women who described themselves as “very happy” to 33.1% among those who were “very unhappy”. At the community level, the prevalence of DH against women was higher in rural areas (20.9%) in comparison with their urban counterparts (16.5%). Prevalence varied significantly across regions, with Yobe showing the highest rate (45.1%) and Ogun (4.6%) the lowest.

For a visual representation of the extent of DH experienced by women at the regional level in Nigeria, the prevalence estimates were plotted against the predictor variable “Regions,” as shown in Figure 2. Kano, where 23.6% of women reported experiencing DH, was selected as the reference for comparison because its prevalence is close to the median among all Nigerian states. Choosing a mid-range state as the reference allows for clearer interpretation of relative differences in DH prevalence across states with both lower and higher incidences. The prevalence rates span from 4.6% to 45.1% across the regions. Based on the standard deviation from the national mean as a classification benchmark, the regions were grouped into color-coded categories: dark green for significantly below average, light green for average, light brown for moderately above average, and dark brown for exceptionally high prevalence (over 2.5 standard deviations above the national mean). The spatial distribution reveals stark regional inequalities. Zamfara (dark brown), a socioeconomically disadvantaged region, exhibited an alarmingly high prevalence, while regions shaded in green reported lower levels of DH.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of discrimination and harassment against women in Nigeria.

3.4. Predictors of Discrimination and Harassment Against Women in Nigeria

Table 3 presents factors that contribute to the likelihood of women experiencing DH as identified through logistic regression analysis. The study found that younger women were more likely to face any form of DH. Specifically, compared to women aged 35–49, those aged 25–34 (OR = 1.331, 95% CI: 1.180–1.502, p < 0.001) had higher odds of experiencing DH. Concerning level of education, women with higher or tertiary education (OR = 0.686, 95% CI: 0.560–0.842, p < 0.001) were 31.4% less likely to experience DH than those without formal education. Unmarried women (OR = 1.367, 95% CI: 1.196–1.562, p < 0.001) were 36.7% more likely to be exposed to DH compared to those who were currently married/in union. The results did not indicate a statistically significant correlation between household wealth and the likelihood that women experienced DH, as the odds ratios across all categories were close to 1.

Table 3.

Binary logistic regression between socio-demographic characteristics and prevalence of discrimination and harassment against women.

In terms of the ethnicity of the household head, Kanuri women (OR = 0.523, 95% CI: 0.331–0.826, p = 0.005) were 47.7% less likely to experience DH than the Fulani. Compared to women who felt very safe at home alone after dark, those who felt very unsafe (OR =2.120, 95% CI: 1.554–2.891, p < 0.001) were significantly more likely to feel discriminated against and harassed. Although women who had never been circumcised (OR = 0.949, 95% CI: 0.843–1.068, p = 0.385) were slightly less likely to experience DH than those who had, the difference was not statistically significant. A discernible association was observed between women’s inability to get pregnant and their likelihood of experiencing DH. Specifically, women who could not become pregnant (OR = 1.20, 95% CI: 1.04–1.39) were 20% more likely to experience DH than those who could. Similarly, self-reported happiness was negatively associated with the odds of experiencing DH. Women who reported feeling very unhappy were 3.101 times more likely to experience DH compared to those who felt very happy.

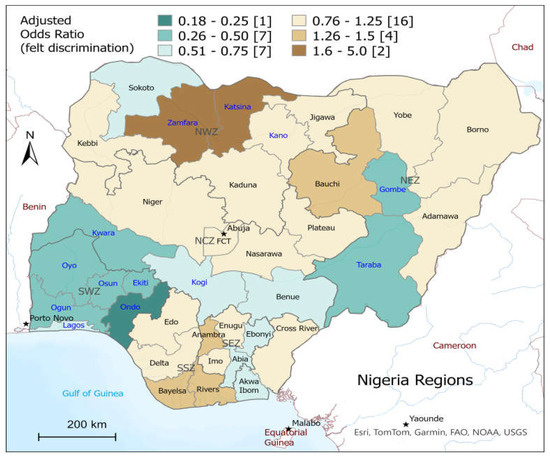

Women residing in rural areas (OR = 1.140, 95% CI:1.006–1.292, p = 0.040) were 14% more likely to face DH than those in urban areas. Compared to women in the region of Kano, those in Zamfara were over five times more likely to experience DH (OR = 5.045, 95% CI: 3.072–8.288, p < 0.001). Conversely, women in southern states such as Ondo (OR = 0.176, 95% CI: 0.104–0.298, p < 0.001), Ogun (OR = 0.300, 95% CI: 0.189–0.476, p < 0.001), and Osun (OR = 0.335, 95% CI: 0.213–0.528, p < 0.001) were significantly less likely to experience DH.

Figure 3 visually presents the adjusted odds ratios (AORs) for self-reported experiences of DH against women across the 36 Nigerian states and the FCT. The AORs are categorized into six categories, with the range of 0.76–1.25 indicating no statistically significant difference from the reference state, Kano. States shaded in darker green (e.g., Oyo, Kwara, Ogun) had significantly lower odds (AOR < 0.50), indicating that women in these areas were less likely to report experiencing DH compared to Kano. In contrast, states shaded in darker brown (e.g., Zamfara, Katsina) had AORs above 1.5, indicating a significantly higher likelihood of women experiencing DH. States shaded in beige or grey-brown tones, as well as those with black labels, did not differ significantly from the reference category (Kano). Notably, states such as Gombe, Taraba, and Kogi—highlighted with blue labels—had AORs that were statistically significant and deviate from the reference category.

Figure 3.

Regional distribution of odds ratios for discrimination and harassment.

4. Discussion

Discrimination and harassment (DH), deeply rooted in entrenched societal norms, constantly marginalize women across sub-Saharan Africa (Arthur-Holmes et al. 2023). In line with other contexts (Arthur-Holmes et al. 2023; Awusi et al. 2023; Brown et al. 2021), DH remains a persistent issue among women in Nigeria, despite the existence of policy initiatives aimed at promoting gender equality. Findings from the 2021 MICS indicate that 18.9% of women of reproductive age have experienced at least one form of DH. This enduring prevalence underscores the urgent need for collaborative action among policymakers, civil society, and community leaders to eliminate DH in all its forms.

This study reveals several key insights into the prevalence of DH against women aged 15–49 based on seven possible grounds. Notably, age emerged as the most common reason in Nigeria, which parallels the findings from a study conducted in the United States (Clarke 2007). However, this contrasts with a recent study that identified sex as the primary cause of DH in the United Kingdom (Bayrakdar and King 2023). This discrepancy may reflect contextual differences in socio-cultural expectations, legal enforcement effectiveness, and community-level perceptions of DH.

Employing both bivariate and multivariate analyses, our findings demonstrate that the risk of DH cannot be attributed to isolated factors but rather emerges from the interplay between individual and community characteristics. At the individual level, age was a significant indicator, with younger women facing higher risks of DH than those aged 35–49. This finding coheres with evidence from New Zealand (Howard et al. 2024), Bangladesh (Haq et al. 2023), and the United States (Roscigno 2019). A possible explanation for this could be that entrenched gender norms and stereotypes often portray younger women as less authoritative or more submissive, making them more susceptible to control, coercion, and harassment (Para-Mallam 2010).

The likelihood of experiencing DH has been found to decrease with higher levels of education, since education equips women with greater awareness of their rights and improved access to formal reporting mechanisms (Alam et al. 2024; Assari 2020). However, an American study by Andersson and Harnois (2020) argued that higher education is associated with a greater likelihood of perceiving gender discrimination at work, largely because more educated women are overrepresented in male-dominated occupations and are more attuned to subtle forms of bias. In this study, women with secondary education were unexpectedly more vulnerable than those with only primary education, possibly because their increased participation in social and economic activities heightens exposure while lacking the institutional and social support available to highly educated peers (Roscigno 2019).

Several studies have revealed that women who had never been married/in union are more likely to be discriminated against and harassed than those currently married (Alam et al. 2024; Haq et al. 2023; Liu and Wilkinson 2017), which concurs with the findings of this study. A Ghanaian study indicates that unmarried women may face greater scrutiny and social judgment due to prevailing norms that portray them as more independent or less protected (Kyei et al. 2024). On the contrary, marital status confers women’s social identity and respectability, which can deter unsolicited attention in patriarchal communities (Bako and Syed 2018; Maheshwari et al. 2025; Wood et al. 2024).

It should, however, be noted that wealth status did not significantly predict the likelihood of experiencing DH against women, contrasting with previous research in Bangladesh that identified wealth as a key determinant (Alam et al. 2024). This study confirms that ethnicity highly shapes women’s exposure to DH, which echoes the observation in an American study (Walsh et al. 2022). Women from the Edo group had higher odds of reporting such experiences compared to Fulani women. It may be that cultural norms in Edo society, which celebrate female beauty while also prescribing modesty, create conflicting expectations that increase women’s exposure to DH (Bako and Syed 2018; Maheshwari et al. 2025; Okongwu 2024). Kanuri women, by contrast, had significantly lower odds, possibly because their culture is strongly influenced by Islam, which emphasizes gender segregation and restricts women’s public visibility and interaction (Para-Mallam 2010). Women who felt “unsafe” or “very unsafe” when alone at night were more likely to face DH, which is supported by an Australian study (Bastomski and Smith 2017). Women who were unable to conceive were more likely to be discriminated against and harassed, corresponding with the observation by Taebi et al. (2021) that infertile women in Iran tend to face social discrimination and self-stigma which threaten their psychosocial well-being and self-esteem. Our findings suggest that lower levels of happiness increase women’s vulnerability to DH, whereas a US study identified the inverse pathway, showing that experiences of DH were associated with reduced happiness and greater psychological distress (Padela and Heisler 2010). Together, these findings underscore a bidirectional relationship between DH and happiness.

At the community level, women in rural areas had higher odds of experiencing DH than their urban counterparts, paralleling the findings of a Canadian study that reported DH in rural areas was double that in urban areas (Wood et al. 2024). It is possible that isolation and community pressures to conform in rural areas may discourage women from resisting DH treatment (Paula et al. 2023). However, this contrasts with the findings of contradicting the finding of Alam et al. (2024) in Bangladesh, where lower DH rates were reported in rural contexts. Significant regional disparities were observed, with women in Zamfara and Katsina being more likely to experience DH. These regions have been affected by armed conflict, rural banditry, and spillover from the Boko Haram insurgency (Aluede 2023). This prolonged insecurity has heightened women’s exposure to DH, especially in displacement settings, while weak law enforcement allows perpetrators to act with impunity.

5. Conclusions

DH remains a significant public health and human rights concern for women aged 15–49 in Nigeria. In addition to causing immediate psychological and physical harm, DH results in broader social and economic inequalities, underscoring the urgency of addressing its root causes. This study revealed that factors such as age, education, marital/union status, ethnicity of household head, perceived safe at home alone after dark, fertility status, subjective happiness, area of residence, and region were significantly associated with the prevalence of DH against women aged 15–49 in Nigeria.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

This study revealed several findings that diverge from prevailing theoretical expectations. In particular, neither wealth nor the attainment of secondary education appeared to reduce women’s experiences of DH. This challenges traditional resource-based theories, such as human capital (Eide and Showalter 2010) and stratification theories (Barone et al. 2022), which posit that greater socioeconomic resources automatically shields individuals from adverse social consequences. One possible explanation is that secondary education coincides with a critical period of socialization into prevailing gender norms, which may offset its protective effects. Similarly, wealth may not shield individuals from systemic forms of DH, indicating that structural and cultural forces operate independently of individual resources. These anomalous results highlight the limitations of resource-based explanations of social inequality and underscore the need for further investigation into the mechanisms linking education, wealth, and experiences of DH.

5.2. Recommendations for Practice

To mitigate the prevalence of DH, we recommend building on ongoing interventions and accelerating efforts to address legal, community, cultural drivers of DH. Important initiatives are already in place, but there is a need to scale up and strengthen these actions for greater impact. First, the government should review and strengthen anti-DH legislation, providing clear definitions, scope, and legal consequences for violations. Law enforcement capacity should be reinforced, particularly in high-risk regions such as Zamfara and Katsina to ensure perpetrators are held accountable. Second, community-level interventions should be scaled up to challenge entrenched social norms that marginalize women. Partnerships with community leaders, religious authorities, and local organizations remain essential to raising awareness, addressing stereotypes, and fostering inclusive environments. Special programs may be needed in rural areas to reduce isolation and increase women’s access to support. Third, ongoing educational and vocational initiatives should be expanded, with particular focus on women most susceptible to DH (e.g., ages 25–34). Vocational training and economic empowerment initiatives can reduce women’s vulnerability by enhancing independence and social participation. Women with secondary education, who were found to be particularly exposed, would benefit from structured mentorship and institutional support networks. Fourth, current interventions should increasingly integrate mental health services to address the psychological impacts of DH. Programs that promote happiness, reduce social isolation, and support wellbeing can mitigate both the risk and long-term consequences of DH.

5.3. Recommendations for Future Research

Recommendations for future research on DH against women include longitudinal interventions, following examples such as Ford-Gilboe et al. (2020), to track how women’s experiences and coping strategies evolve in response to targeted programs over time. In addition, comparative analyses with other countries are needed to examine how cultural contexts, social structures, and policy frameworks shape both the prevalence of DH and the effectiveness of mitigation strategies. While surveys are valuable for identifying broad patterns, interviews with women and community members are recommended to explore why wealth does not predict DH prevalence and to uncover the social and cultural mechanisms behind this outcome. This study captured DH prevalence against women but did not contextualize the circumstances of occurrence. Future research might consider investigating this phenomenon within workplaces, leadership, and educational settings to gain deeper insights. Finally, adopting an intersectional approach to examine DH among adolescents, LGBTQ+ individuals, and women with disabilities is recommended, which can reveal how gender interacts with other social identities to shape unique vulnerabilities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z., P.N. and T.S.; methodology, Y.Z. and T.S.; software, Y.Z. and T.S.; vali-dation, Y.Z. and P.N.; formal analysis, Y.Z.; investigation, Y.Z.; resources, P.N.; data curation, Y.Z. and T.S.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Z.; writing—review and editing, T.S. and P.N.; visualization, Y.Z. and T.S.; supervision, P.N. and T.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be accessed through the official UNICEF MICS website.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all those who contributed to the completion of this research. We especially thank UNICEF and the government of Nigeria for granting access to the MICS, which provided the essential data for our analysis. We are also thankful to the Canadian Hub for Applied and Social Research (CHASR) for their valuable assistance with geospatial modelling. Finally, we appreciate the insightful feedback and support from our fellow researchers and students who helped shape the direction of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aborisade, Richard A. 2022. “At your service”: Sexual harassment of female bartenders and its acceptance as “norm” in Lagos metropolis, Nigeria. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 37: 6557–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeliyi, Timothy, Lawrence Oyewusi, Ayogeboh Epizitone, and Damilola Oyewusi. 2022. Analysing factors influencing women unemployment using a random forest model. Hong Kong Journal of Social Sciences 60: 382–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabi, T., M. Bahah, and S. O. Alabi. 2014. The girl-child: A sociological view on the problems of girl-child education in Nigeria. European Scientific Journal 10: 393–409. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, M. Iftakhar, Nigar Sultana, and Humaira Sultana. 2024. Prevalence and determinants of discrimination or harassment of women: Analysis of cross-sectional data from Bangladesh. PLoS ONE 19: e0302059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aluede, Jackson A. 2023. La insurgencia de Boko Haram en la región nororiental de Nigeria desde 2010: Una perspectiva transnacional. Historia Actual Online 62: 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, Matthew A., and Catherine E. Harnois. 2020. Higher exposure, lower vulnerability? The curious case of education, gender discrimination, and women’s health. Social Science & Medicine 246: 112780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur-Holmes, Francis, Richard Gyan Aboagye, Louis Kobina Dadzie, Ebenezer Agbaglo, Joshua Okyere, Abdul-Aziz Seidu, and Bright Opoku Ahinkorah. 2023. Intimate partner violence and pregnancy termination among women in Sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 38: 2092–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assari, Shervin. 2020. Social epidemiology of perceived discrimination in the United States: Role of race, educational attainment, and income. International Journal of Epidemiologic Research 7: 136–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awusi, Mary, David Addae, and Olivia Adwoa Tiwaa Frimpong Kwapong. 2023. Tackling the legislative underrepresentation of women in Ghana: Empowerment strategies for broader gender parity. Social Sciences & Humanities Open 8: 100717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakari, Salihu, and Fiona Leach. 2007. Hijacking equal opportunity policies in a Nigerian college of education: The micropolitics of gender. Women’s Studies International Forum 30: 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bako, Mandy Jollie, and Jawad Syed. 2018. Women’s marginalization in Nigeria and the way forward. Human Resource Development International 21: 425–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, Carlo, Florian R. Hertel, and Oscar Smallenbroek. 2022. The rise of income and the demise of class and social status? A systematic review of measures of socio-economic position in stratification research. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 78: 100678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastomski, Sara, and Philip Smith. 2017. Gender, fear, and public places: How negative encounters with strangers harm women. Sex Roles 76: 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayrakdar, Sait, and Andrew King. 2023. LGBT discrimination, harassment and violence in Germany, Portugal and the UK: A quantitative comparative approach. Current Sociology 71: 152–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazaanah, Prosper, and Pride Ngcobo. 2024. Shadow of justice: Review on women’s struggle against gender-based violence in Ghana and South Africa. SN Social Sciences 4: 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Allison, Gabrielle Bonneville, and Sarah Glaze. 2021. Nevertheless, they persisted: How women experience gender-based discrimination during postgraduate surgical training. Journal of Surgical Education 78: 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, Linda. 2007. Sexual harassment law in the United States, the United Kingdom and the European Union: Discriminatory wrongs and dignitary harms. Common Law World Review 36: 79–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darmayasa, I. Made, William Setiawan, and Raymond Natanael. 2023. Post-trauma stress disorder in sexual harassment: A case report. European Journal of Medical and Health Sciences 5: 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devis-Devis, José, Sofía Pereira-Garcia, Alexandra Valencia-Peris, Jorge Fuentes-Miguel, Elena Lopez-Canada, and Víctor Perez-Samaniego. 2017. Harassment patterns and risk profile in Spanish trans persons. Journal of Homosexuality 64: 239–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eide, Eric R., and Mark H. Showalter. 2010. Human capital. In International Encyclopedia of Education, 3rd ed. Edited by Penelope Peterson, Eva Baker and Barry McGaw. Oxford: Elsevier, pp. 282–87. [Google Scholar]

- Ford-Gilboe, Marilyn, Colleen Varcoe, Kelly Scott-Storey, Nancy Perrin, Judith Wuest, C. Nadine Wathen, James Case, and Nancy Glass. 2020. Longitudinal impacts of an online safety and health intervention for women experiencing intimate partner violence: Randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health 20: 1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, Rachel. 2020. The impact of international human rights law ratification on local discourses on rights: The case of CEDAW in Al-Anba reporting in Kuwait. Human Rights Review 21: 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianakos, Arianna L., Julie A. Freischlag, Angela M. Mercurio, R. Sterling Haring, Dawn M. LaPorte, Mary K. Mulcahey, Lisa K. Cannada, and John G. Kennedy. 2022. Bullying, discrimination, harassment, sexual harassment, and the fear of retaliation during surgical residency training: A systematic review. World Journal of Surgery 46: 1587–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammond, Wizdom Powell, Marion Gillen, and Irene H. Yen. 2010. Workplace discrimination and depressive symptoms: A study of multi-ethnic hospital employees. Race and Social Problems 2: 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haq, Iqramul, Md Mizanur Rahman Sarker, and Sharanon Chakma. 2023. Individual and community-level factors associated with discrimination among women aged 15–49 years in Bangladesh: Evidence based on multiple indicator cluster survey. PLoS ONE 18: e0289008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaton, Matthew M. 2024. History of Nigeria. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heilman, Madeline E., and Suzette Caleo. 2018. Combatting gender discrimination: A lack of fit framework. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 21: 725–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, Chloe, Nickola C. Overall, Danny Osborne, and Chris G. Sibley. 2024. Women’s experiences of sexual harassment and reductions in well-being and system justification. Sex Roles 90: 981–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Yeqian, Terence C. Chua, Robyn P. M. Saw, and Christopher J. Young. 2018. Discrimination, bullying and harassment in surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World Journal of Surgery 42: 3867–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Hyun. 2013. The prevention and handling of the missing data. Korean Journal of Anesthesiology 64: 402–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, Vandita. 2024. The development of indirect discrimination law in India: Slow, uncertain, and unsteady. Indian Law Review 8: 306–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyei, Simon, Bright Agorkpa, Beatrice Benewaa, and Nora Shamira Narveh Sadique. 2024. Marital power play in patriarchal society, a qualitative study of Ghanaian religious wives’ perspectives. Discover Global Society 2: 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamarche, Lucie. 2013. The Canadian experience with the CEDAW: All women’s rights are human rights—A case of treaties synergy. In Women’s Human Rights: CEDAW in International, Regional and National Law. Edited by Anne Hellum and Henriette Sinding Aasen. Studies on Human Rights Conventions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 358–84. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Hui, and Lindsey Wilkinson. 2017. Marital status and perceived discrimination among transgender people. Journal of Marriage and Family 79: 1295–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, Greeni, Lizbeth A. Gonzalez-Tamayo, and Adeniyi D. Olarewaju. 2025. An exploratory study on barriers and enablers for women leaders in higher education institutions in Mexico. Educational Management Administration & Leadership 53: 141–57. [Google Scholar]

- Manzi, Francesca, Suzette Caleo, and Madeline E. Heilman. 2024. Unfit or disliked: How descriptive and prescriptive gender stereotypes lead to discrimination against women. Current Opinion in Psychology 60: 101928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesa-Chavez, Fernanda, Andrea Castro-Sanchez, and Cynthia Villarreal-Garza. 2025. Gender discrimination and sexual harassment experienced by women physicians in Mexico. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 08862605251355627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, Ashlee, Melissa Fong-Emmerson, Steven D’Alessandro, and Marie Ryan. 2025. DEI and discrimination in the marketing industry: Exploring the lived experiences in the workplace. Evidence from Western Australia. Australasian Marketing Journal, 14413582251358509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics, Statistician General of the Federation, and Unicef. 2021. 2021 Nigeria Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) & National Immunization Coverage Survey (NICS) Statistical Snapshots. Abuja: National Bureau of Statistics and UNICEF. Available online: https://mics.unicef.org/download-tracker/6541/11416 (accessed on 22 March 2025).

- Newman, Constance. 2014. Time to address gender discrimination and inequality in the health workforce. Human Resources for Health 12: 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nnama-Okechukwu, Chinwe U., and Hugh McLaughlin. 2023. Indigenous knowledge and social work education in Nigeria: Made in Nigeria or made in the West? Social Work Education 42: 1476–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okongwu, Onyeka C. 2024. The need for a national legislation for the protection of women from workplace discrimination in Nigeria: Lessons from the existing UK legal framework. International Journal of Discrimination and the Law 25: 313–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olonade, Olawale Y., Blessing O. Oyibode, Bashiru Olalekan Idowu, Tayo O. George, Oluwakemi S. Iwelumor, Mercy I. Ozoya, Matthew E. Egharevba, and Christiana O. Adetunde. 2021. Understanding gender issues in Nigeria: The imperative for sustainable development. Heliyon 7: e07622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owen, David. 2024. The value of the concept of discrimination in contexts of migration: The case of structural discrimination. Ethics & Global Politics 17: 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padela, Aasim I., and Michele Heisler. 2010. The association of perceived abuse and discrimination after September 11, 2001, with psychological distress, level of happiness, and health status among Arab Americans. American Journal of Public Health 100: 284–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Para-Mallam, Funmi J. 2010. Promoting gender equality in the context of Nigerian cultural and religious expression: Beyond increasing female access to education. Compare 40: 459–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paula, Michelle Barbosa Moratório de, Ana Beatriz Azevedo Queiroz, Ívis Emília de Oliveira Souza, Anna Maria de Oliveira Salimena, Helen Petean Parmejiani, and Ana Luiza de Oliveira Carvalho. 2023. Identity dimension of rural women and the sexual and reproductive health. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem 76: e20220298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankine, Jenny. 2001. The great, late lesbian and bisexual women’s discrimination survey. Journal of Lesbian Studies 5: 133–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roscigno, Vincent J. 2019. Discrimination, sexual harassment, and the impact of workplace power. Socius 5: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runyan, Anne Sisson, and Rebecca Sanders. 2021. Prospects for realizing international women’s rights law through local governance: The case of cities for CEDAW. Human Rights Review 22: 303–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son Hing, Leanne S., Nouran Sakr, Jessica B. Sorenson, Cailin S. Stamarski, Kiah Caniera, and Caren Colaco. 2023. Gender inequities in the workplace: A holistic review of organizational processes and practices. Human Resource Management Review 33: 100968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soroosh, Garshasb, Hammed Ninalowo, Andrew Hutchens, and Sonya Khan. 2015. Nigeria Country Report. Chevy Chase: RAD-AID International. Available online: https://rad-aid.org/wp-content/uploads/Nigeria-Country-Report-Final.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2015).

- SteelFisher, Gillian K., Mary G. Findling, Sara N. Bleich, Logan S. Casey, Robert J. Blendon, John M. Benson, Justin M. Sayde, and Carolyn Miller. 2019. Gender discrimination in the United States: Experiences of women. Health Services Research 54 S2: 1442–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taebi, Mahboubeh, Nourossadat Kariman, and Hamid Alavi Majd. 2021. Infertility stigma: A qualitative study on feelings and experiences of infertile women. International Journal of Fertility & Sterility 15: 189–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udu, Eseni Azu, Anoke Uwadiegwu, and Joyce Nenna Eseni. 2023. Evaluating the enforcement of the rights of women under the convention on the elimination of all forms of discrimination against Women (CEDAW) 1979: The Nigerian experience. Beijing Law Review 14: 764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. 2025. UNESCO Launches the Global Alliance on Racism and Discriminations After the 4th Edition of the Global Forum. Last Modified 22 January 2025. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/unesco-launches-global-alliance-racism-and-discriminations-after-4th-edition-global-forum (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Walsh, Kate, Amanda K. Gilmore, Simone C. Barr, SPatricia Frazier, Linda Ledray, Ron Acierno, Kenneth J. Ruggiero, Dean G. Kilpatrick, and Heidi S. Resnick. 2022. The role of discrimination experiences in postrape adjustment among racial and ethnic minority women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 37: 17325–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardhani, Lita Tyesta Addy Listya, and Aga Natalis. 2024. Assessing state commitment to gender equality: A feminist legal perspective on legislative processes in Indonesia and beyond. Multidisciplinary Reviews 7: 2024120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, Karen, Crystal J. Giesbrecht, Carolyn Brooks, and Kayla Arisman. 2024. “I couldn’t leave the farm”: Rural women’s experiences of intimate partner violence and coercive control. Violence Against Women, 10778012241279117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusuf, Noah. 2010. Experience of sexual harassment at work by female employees in a Nigerian work environment. Journal of Human Ecology 30: 179–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).