“I Feel Like a Lot of Times Women Are the Ones Who Are Problem-Solving for All the People That They Know”: The Gendered Impacts of the Pandemic on Women in Alaska

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Goal and Research Questions

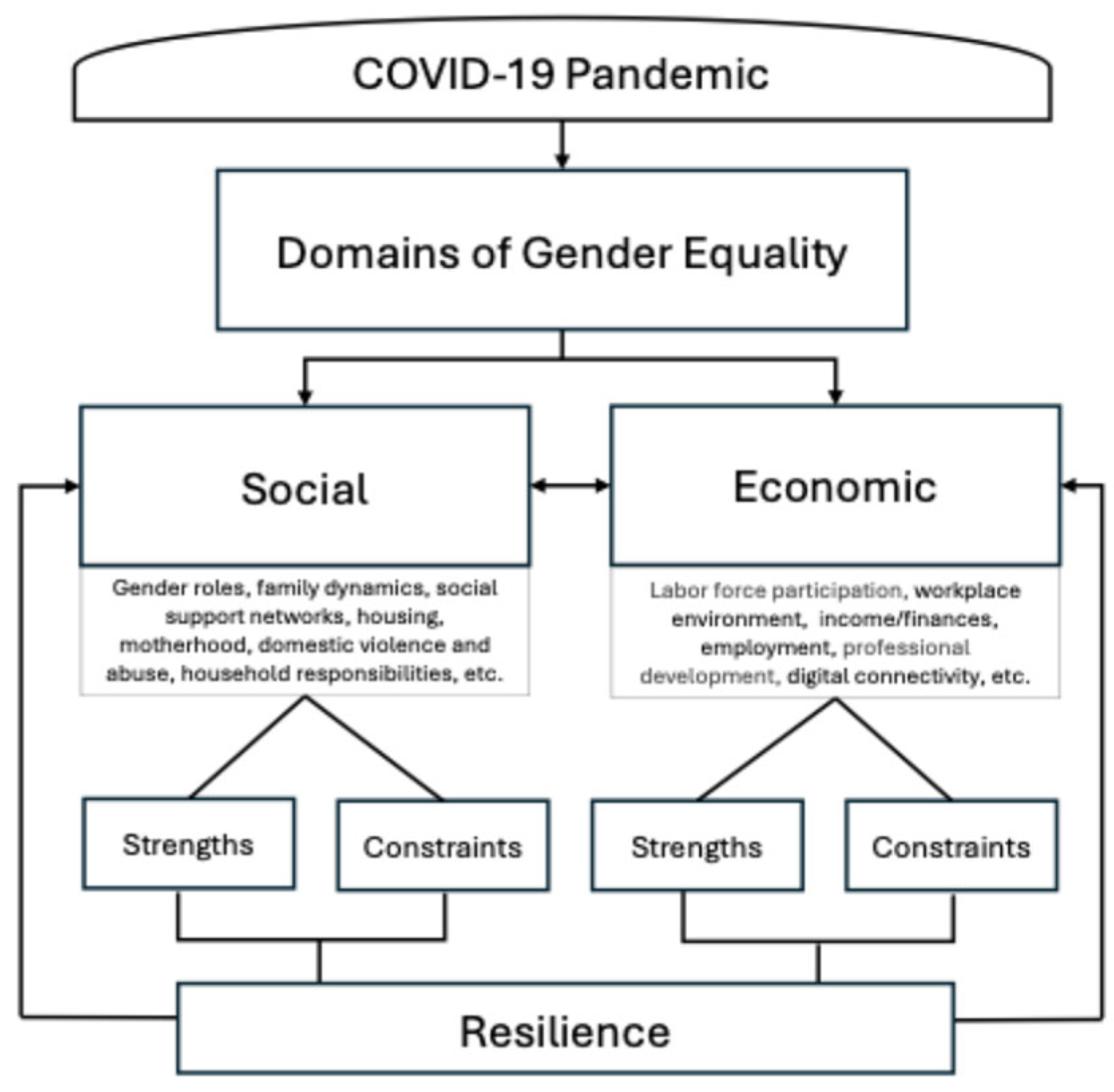

1.2. Conceptual Framework

2. Methods

2.1. Study Region

2.2. Research Approach

2.3. Authors Positionality

3. Results

3.1. Social Domain

3.1.1. Strengths for Resilience Within the Social Domain

“There were little pods formed. I think people were just looking for little pods that they would feel like you wouldn’t get infected. I thought it was a very creative move that a lot of women did create these pods to be able to meet their own needs and still fulfill their functions at work.”(Anchorage, 60s.)

“One thing that has positively come from the pandemic is, despite people being so disconnected and there being less opportunities for ’community,’ I feel like people have risen to the occasion… and created micro communities… that never existed before…”(Anchorage, 30s.)

“I feel like a lot of times women are the ones who are problem-solving for all the people that they know whether it’s their friends or their relatives or just trying to make sure that people are connected to the resources that they need or finding out what they are or all of that.”(Anchorage, 30s.)

“I’ve never taken kids to school or picked them up before. And then that kind of became just an active service that I could do for some of my friends with kids who needed to have a job interview at that time or needed to be in a meeting … So being able to help them out in those small ways has been really meaningful.”(Anchorage, 30s.)

“I did a lot of mentoring and most of my mentoring was towards women… I found out … that it was one of the most positive sides of my job… Before I went back to work <after the pandemic–authors>, I was frustrated because I had all of this knowledge, 30 years of being a woman and working my way up, it was like, ’I’m wasted. I want to mentor again.’ Most of the employees that we had were female, and I got a lot of very positive feedback from women, and there’s a part of me that really liked being told that I was helpful.”(Anchorage, 60s.)

“I’ve realized a couple things in the pandemic… We were forced to slow down… I was enjoying the times when we didn’t run around like chickens with our heads cut off, constantly driving kids to soccer practice or to choir concerts… It is nicer and calmer now that we can slow down and appreciate…the times where we can just be without having to hustle. And prior to the pandemic, my day was like clockwork–I’d get up early in the morning, make sure kid one gets to school, wake up second kid, make coffee for the husband, make sure lunches are packed, get myself to work, take my lunch break, go to the gym, pick up kid one from school, pick up kid two, come home, make dinner, make sure homework’s done, rinse, and repeat… <During the pandemic–authors> the personal time schedule has really changed… I have taught myself how to relax a little bit more.”(Anchorage, 40s.)

“We have this myth of the supermom in which women can do everything. They can get pregnant and have a child and be back in a bikini in a month. And I think sometimes women hold each other to that standard as much as men hold women to that standard. We all need to give each other a break and understand we cannot do it altogether. And that whole striving to be everything for everybody, something’s got to give there. And not doing it all... and that will open space for other people, the men in our lives…to come forward and do more. It’s not the default responsibility of women by virtue of biology.”(Anchorage, 60s.)

“I am still working. My husband is not currently working and so he is more responsible for the household stuff. Yes, he does a lot of the cooking and the laundry. So, that’s just the way it is.”(Anchorage, 60s.)

3.1.2. Constraints to Resilience Within the Social Domain

“I think a man is thought to be the provider, the breadwinner, the person that’s making the most money, and he’s probably gone the most for work. He provides the stability for the home in the forms of financial stability. But women are then put into this corner of being the emotional providers, the persons keeping track of every little detail <in the household–authors>.”(Anchorage, 30s.)

“The burden of childcare and schooling primarily falls on women. Their father was working a job that would not allow for any leeway during the pandemic, and so their education, health, safety fell to me.”(Anchorage, 40s.)

“I know personally several women who basically stepped back from their careers for their families, tried to work at home and have families… I’ve got one friend who she started seeing a therapist, and she went on some antidepressants because it just was overwhelming for her.”(Anchorage, 60s.)

“I tend to think that men get to do more of the fun things, so more of the playtime with the kids… let’s say maybe playing with kids like hockey or taking them to fish together… And women tend to take on the less fun tasks, just because we tend to be more detail oriented, but also can see the big picture of everything that’s at play and that needs to get done… I don’t want to sound too biased, I do think that men get to do more of the fun things…. And I think that that dynamic still exists in a lot of families. And that was hard <during the pandemic>. I think that really wears on women mentally, and it changes your relationship structure. And I think a lot of people underwent their relationship structure changing to an uncomfortable degree.”(Anchorage, 30s.)

“I know that domestic violence and murders have increased. I was really scared of what was happening to women. And murder of pregnant women has gone up so much since the start of the pandemic… Pregnancy in general is the highest risk time for women in abusive relationships and in terms of abuse. Always the time of escalation and risk.”(Anchorage, 40s.)

“In Nome, there is a high rate of alcoholism, and women had to stay home <during the pandemic>. You had to stay in the same household with your abuser. You had nowhere else to go… One of the major issues we face in Nome is a housing crisis. There’s just not enough housing to go around… We do have a women’s shelter here, but there’s limited space as well. A lot of women just end up going back to their abusers… It seems like the amount of domestic violence and trauma to women and children I think went up in our region during the pandemic.”(Nome, 40s.)

“The majority of houses here are not safe for individuals, especially kids and women, to be in. Here, it’s typical for two to three families to live in one house where you’ve got 15 people, that are crowded, sleeping on couches, sleeping on the floor, and don’t have the options to isolate if they’re feeling sick.”(Nome, 20s.)

“<In Nome>, there’s just not enough housing. We have a lot of lousy landlords. They rent dilapidated rentals that are probably not even up to code to people. I’ve heard stories of people going without heat for a year because the landlord won’t fix the furnace or the heaters. In winter, it’s worse because your pipes freeze and then you don’t have running water, or you can’t use the sink. You can’t shower, you can’t bathe, you can’t wash hands. And then illness just takes over because of that…”(Nome, 20s.)

“I just remember that horrible feeling a lot of times where I feel like I’m not doing a good job at work, I’m not doing a good job at home, I’m just trying to do everything.”(Anchorage, 60s.)

“I hear a lot about the parents’ guilt, they’re working these crazy hours trying to work from home and also trying to support their kids and not being able to really carve out any time for themselves. And that definitely impacts your mental health and your physical health, and the health of your family.”(Anchorage, 30s.)

“I think women are more social in general, and if they’re not working then they don’t get a lot of interaction with other women so going through all that just kind of made it worse. Everybody was more separated and less likely to gather together as a tribe.”(Anchorage, 30s.)

“Nome’s a very transient town… We have a lot of people from all over getting a job here, working for two years, and are gone, and then there’s a small core of people that have been here for many years… That affects a lot of the relationships.”(Nome, 20s.)

“Any in-person mom playdate groups were completely killed off by COVID… all of the new online parent groups… I really feel like isn’t ideal, because if you have a support structure already, I think you’re going to be okay, but if you’re in a place where you need to form a new support structure, then I think you’re really going to suffer, because all of those places where you can forge those really meaningful connections have moved online. There’s absolutely value in those things existing at all, in whatever form they take, but I don’t think it’s ever going to be as good as something where you can meet face to face.”(Anchorage, 20s.)

“There’s a hesitation of people in my family who believe in the pandemic, believe in health and safety, and then those that don’t and think that it’s a total hoax and think that the rest of us are crazy and we’re just being paranoid. It’s shifted a lot of relationship dynamics… It’s not like we’re not meeting as a whole united family despite different political stances, which we’ve always had. But now, the tensions are so high around it, that I feel like there is some irreparable damage that has been done where things are just really divisive… I would say relationships have not been restored after the pandemic.”(Anchorage, 30s.)

“COVID pandemic certainly changed us. I’m more profoundly and sadly aware of how little the United States cares… about children and women… <Regarding–authors> the administration here in Alaska—“Well, what about childcare? You can’t open the economy back up if there’s nowhere for kids to go. What are you going to do? Leave them at home alone?” I knew that the administration didn’t care about children or women, but to see it echoed in so many places was pretty heartbreaking.”(Anchorage, 40s.)

“Things have gotten worse, … all the inequities have gotten worse. Women were left in charge of holding the bag for the total societal refusal to prioritize babies and children first.”(Anchorage, 40s.)

“Mental health is the biggest thing… We’re <geographically> separated, so we already have the isolation issue… we deal with darkness here, we deal with seclusion, isolation, and then on top of having to isolate yourself from your friends and family even more <during the pandemic–authors>, it added more of a stressor to the whole thing… And then the fear of people now and adding all that in on top of having to keep a job down.”(Nome, 20s.)

“Everyone is falling through the cracks… Our healthcare system, things that were already spread thin… There aren’t enough therapists to meet with us… I wanted to see a personal therapist… I eventually found one, and it was months of waiting before I could even have my first appointment. And I had basically four months in between every appointment… and then my insurance didn’t cover it … and that was so cost prohibitive! I ultimately chose to stop seeing that therapist… The financial stress of this is going to cause my anxiety to go up more than it already is… It’s very challenging to have something as basic as… mental healthcare…in Alaska.”(Anchorage, 30s.)

3.2. Economic Domain

3.2.1. Strengths for Economic Resilience During the Pandemic

“In academia, they’re just obsessed with meetings, and most of them are completely unproductive… Such a waste of time! Nowadays, we do it on Zoom and I can turn off my video and I can pipe in when needed. But meanwhile, I can do something useful at home… So, I find it very positive.”(This quote has been anonymized to protect the participant’s privacy.)

“Work from home policies were helpful, because if you don’t have childcare, it’s better to at least be home with your kid than leave them home alone.”(Anchorage, 40s.)

“I would say, positively … working from home and less commuting… I get more done if I work from home. I can work more focused, I don’t have distractions… I live quite a ways out of town… and this place can be kind of hairy in the winter with snowstorms and whatnot…. I’ve done more during the pandemic, and I find it very much less stressful.”(Nome, 50s.)

“One of the things that was good that did come out of the pandemic was… more access to different conferences that I wish I would’ve gone to in person before the pandemic and wasn’t able to. I was able to attend these conferences online and take language classes for free or a limited low amount of payment for the classes… And I really enjoyed the conferences that I had attended. One of them was… <on> small women businesses and how they’re boosting the local economy… And then in the midst of the pandemic, I was taking some classes to learn about starting my own business and… how to make business more successful.”(Anchorage, 40s.)

“… I think the thing that was most helpful was we got COVID funding for our Northwest Campus <University of Alaska Fairbanks–authors>, and you could take classes for a very reasonable price. That opened up a lot of doors for women to be more providers at home. For being able to learn how to make … parkas or learn how to knit so that they could make things to sell… The Campus really tries to reach the local needs …”(Nome, 20s.)

“I teach a distance class, and I know a lot of my students live with other people in crowded conditions… Most of them are mothers and wives… And I feel bad for them because it’s clear they don’t have a quiet space to get away from it all. And apparently whoever else is in the house with them takes absolutely no regard to the fact that they’re trying to take a class…I totally admire them for that, because I could not focus in an environment like that. That might have been worse during the pandemic, when everybody was more cooped together.“(This quote has been fully anonymized to protect the participant’s privacy.)

“My colleagues, my team members, we are family… So, I started noticing how much extra…, like emotional labor or just colleague stuff, you put more of yourself into work that you’re really invested in. And when I started seeing more and more cracks <related to the gender pay gap–authors>, my perspective on work has definitely changed.”(Anchorage, 30s.)

“Since I am looking for jobs and because I’ve had some traumatic work experience this year, I’m very much seeking an employer who respects me… I want to learn how they’ll support me as an employee rather than only focusing on what I can do for them. It’s about reciprocity really, and not just in terms of employment, but in all aspects of life.”(Anchorage, 30s.)

“Perspective shifts… Almost all my team had to take a pay cut <during the pandemic–authors>, so we just worked one day less a week…. But I didn’t realize until the next summer that leadership didn’t take a pay cut even though they were working less… One of my <male–authors> colleagues, he was hired on at a higher pay than me. Not only is it appalling because I have 10 more years of work experience… It’s a gender pay gap situation… Then you start thinking about how you’re valued and how we’re placed in the workplace and in your work, your role… It makes you start feeling like you’re not very valuable…”(Anchorage, 30s.)

“I’ve realized… in the pandemic <that–authors> following the corporate dollar doesn’t really seem to have any interest to me anymore,– my relationships with others are more important than anything else…”(Anchorage, 40s.)

“I was in the <one of the top managerial positions> in the company, where I worked for <many> years… And when the pandemic hit… the company made cuts, and my job was eliminated. I was retired for almost a year and a half and realized I was going absolutely crazy because…. I wanted to be in an office… There was an opening for a position…, which is basically fundraising… which I’d never done before, but I have a brain in my head. I applied for it and got it… My life has definitely changed in the last couple of years. Going from working full-time and being the most knowledgeable person in the room to being retired, and then back to working full-time but being the least knowledgeable person in the room was quite an adjustment.”(Anchorage, 60s.)

“I do miss the little kids… <but–authors> I ended up quitting my job because I couldn’t take it anymore. This past year was awful. We had very violent kids and just a lack of resources and support and everyone was really burned out. They <schools–authors> lost a lot of principals, a lot of teachers quit or retired early…, coming to the realization like, ‘My job isn’t worth … risking my life for.’ Now, I’m going to think about doing something different… I would think that technology, doing something with IT or tech would be cool…”(Anchorage, 30s.)

“In this place,… you can find a lot of guys with toolkits, but it’s hard to find someone who truly knows what they’re doing… I have found out that if I just do the work myself, I can do it just as well. So, I’ve spent a lot of my time learning how to replace windows, how to fix floorboards that have rotten, paint the walls, put in new floors, and how to do everything, really. I do it myself now. And what’s amazing is I feel very empowered!”(Nome, 50s.)

“My boss is a phenomenal woman… who is very good at making decisions and very good at supporting her staff. And her goal was to make sure that everybody was taken care of while still making sure the organization could move forward and sustain itself <during the pandemic–authors>… I don’t mind working hard for her when I need to because she supports me on the flip side when I need to be there for my family. She supports that. Her leadership makes a huge difference.”(Anchorage, 30s.)

3.2.2. Constraints to Resilience Within the Economic Domain

“<During the pandemic–authors>, women are then put into this corner of being the emotional providers, the persons keeping track of every little detail regarding kids and house payments and bills and shots and all of the things. I think it’s really spreading women so thin. We were already spread thin <before the pandemic–authors>—the amount that we have to keep track of. Every woman I know with kids has a new to-go file organizer, and has all of the family’s vaccination cards… and keeping track of all these little details”(Anchorage, 30s.)

“I feel that women took the burden and the brunt of childcare. Some of us had to leave our jobs… we took the brunt of that, and it wasn’t just making sure that they were in childcare, but we also became teachers, we also became counselors, we became all the different things that our children couldn’t access because they were <at home–authors> with us.”(Anchorage, 40s.)

“It was really difficult for my friends with kids trying to deal with their own work at home and also having to supervise their kids with their online classes and even just having to be with their kids 24/7 was really challenging for them. I had a friend who said she had no idea that her kids were so difficult: ’I’d do anything, I’d pay teachers anything to just take my kids back. I don’t want them here all day long’.”(Anchorage, 30s.)

“At the beginning of the pandemic, a lot of people were like, ’Oh, this is great <to work from home–authors>.’ But then we look at the reality of it, and people are even busier than they were when they were in the office because now that everything is Zoom, people schedule back-to-back meetings. There’s not even time for bathroom breaks… I think it’s made a lot of jobs feel more constant because there’s this new expectation that you will just work your bones off and never really stop.”(Anchorage, 30s.)

“I was pushed into developing new technological skills that I hadn’t always practiced. I mean, everybody now knows how to Zoom or do Microsoft Teams. Those were not tools I used routinely…It seemed like a stressful time at work. I didn’t feel as much efficacy, I didn’t feel like I was doing as good a job.”(Anchorage, 60s.)

“Not everybody can afford internet here, because it can range anywhere from $200 to $500 a month… And that adds an extra stress…”(Nome, 20s.)

“Women had to stay home to take care of their kids. Ninety percent of the time that’s the way it falls, because 90% of the time, men are making more than the women so it’s the women who have to take the step back and say, “Okay, I’ll stay home and take care of the kids.” Because there was zero childcare… to save your life.”(Anchorage, 40s.)

“I think more acutely and really noticeably, women are the primary caregivers in families typically. And we saw women drop out of the workforce at a much higher level than men. And it’s all tied into the childcare challenges, or even choice of life-work balance. And you always look to, ’Okay, if one of us is going to stay home or not work or work part time, who’s that going to be?’ And it tends to be the person who’s making less. And in our culture, we value women less everywhere, but especially professionally. And so, women dropped out. I think that’s a big problem following the pandemic, but it’s all connected.”(Anchorage, 40s.)

“<During the pandemic–authors>, the existing disparities heightened. Women were not getting promoted in the same way as men… This exposed all the ways in which gender inequities then lead to women having to drop out of the workforce, pick up the load. A lot of these things are cultural.”(Anchorage, 40s.)

“Ultimately, we just need to change our cultural framework because… It’s like, you’re a woman. You’re worth less… We’re probably going to pay you less. We know you’re not going to ask for more. It all builds and builds, and then suddenly you have a 40-year-old woman who’s making less than the 40-year-old guy doing the same thing. And so, it’s hard to change that, but I think real reflection on how we change it long term is needed.”(Anchorage, 40s.)

“A lot of women choose not to work and just to have their husband work because all of their income would be going towards childcare, so they might just stay home because it’s not worth it. I think that’s a really big thing that people spend $2000 to $3000 a month on childcare easily. To have that burden lifted so that they could have the potential for a career to work.”(Anchorage, 40s.)

“Single moms probably had it the worst because they had no one to fall back on. They had nowhere else to go, especially with those with multiple kids, because you can’t afford childcare for them. That’s why I never went back to work full time.”(Anchorage, 40s.)

“<After having a baby–authors>, eventually that was what stopped me from going back to work, was, if I’m going to be sinking all of my money into childcare, it’s more cost effective for me to just not work. The financial aspect was definitely a huge part of it, and especially as then people started returning to work and the cost of childcare kept increasing. Then, people were not able to afford it as much.”(Anchorage, 20s.)

“I think women always pre-pandemic have been dealing with a ‘glass ceiling,’ but I think that ceiling lowered in a negative way during the pandemic.”(Anchorage, 30s.)

“I think that in a lot of settings, women… are not listened to as much, it’s like their perspective isn’t as valuable… A lot of women are isolated from the decision-making and policy in the community because they have all the home duties <and this exacerbated during the pandemic–authors>.”(Anchorage, 60s.)

“Men in our society, they get paid more on the dollar. They rise in their careers faster than women. They’re the ones that are in more management positions. Women are the ones that take more parental leave and are assumed to be the primary caregivers and the ones getting their kids to their healthcare appointments and to school and picked up to soccer lessons… It’s an infuriating thing about our society… that women are not taken as seriously as men.”(Anchorage, 30s.)

“Women always face more challenges in the realm of being respected and listened to in coming up with community solutions. And I think there’s always this vein of like, do these women really know? I think there’s a lot of misogyny built into our culture and also our political structures that expect these men, tough men, to solve problems.”(Anchorage, 40s.)

“I love Alaska, but there is sometimes some toxic masculinity here that needs to be talked about. It can be a difficult community to break a ‘glass ceiling’ in. I work for nonprofits where the leadership team is primarily men. I’ve been told that I wouldn’t understand certain things because I’m a woman, and ’It’s like snowmachining.’ But I’ve been riding the snow machine since I was 10 years old. I can out-ride most guys. But being a woman, I would not understand that. I know we can’t change everyone’s attitudes, but we need to be talking about what this is and why it’s so dangerous… Women are not going to be able to succeed when we’re constantly being held back in this way.”(Anchorage, 40s.)

“The Federal CARES Act came into the state and then the state distributed it… The decisions <on childcare and other social services–authors> were being made by people who did not have children and women in mind.”(Anchorage, 40s.)

“We need more women in positions of leadership, and we need the means in place to allow them to do that while still feeling good about their choices to have a family. Women won’t take on extra leadership roles if they don’t have that support in their community and in their household to extend themselves. Because if we get more women in those positions of leadership, they’re going to be at the table when policymakers are having these conversations about what to do.”(Anchorage, 60s.)

“There’s always the chance and childcare they keep closing… So, if you don’t have a job that is sympathetic… you can’t work from home with a one-year-old running around. It’s ridiculous… Productivity and just you’re online talking to some male colleagues, and they don’t understand that you have no choice but to have this child in the background… Especially when you look at these patriarchal companies that are a typical ’old boys club.’ … Energy, shipping, airline,… the tourism industry, cruises, trains, restaurants …—I feel like there are very male dominated for the upper levels.”(Anchorage, 40s.)

“In Anchorage, we started this school year with students back in, but no buses…We’re all back at the office, and we have no way to get our children back and forth to school… all the way across town. Let’s say you have two children who are in high school and in elementary. Well, the first one has to be at school at 7:30, then the second one has to be at school at 9… Then they need to pick up at 2 o’clock and 3:30. How many jobs are willing to give you that much time? I actually had an opportunity to interview for a job and asked, before I even did the interview, very clearly that I have children, I need a little assistance, and they told me, ’Why don’t you apply again when things are a little bit more normal?’ No accommodation willing. I understand that as a business, that’s their prerogative, but I feel like that automatically puts women into that position. I’m automatically told, ’Okay. Well, <you’re> probably going to hire a man or somebody who doesn’t have kids. Thanks.’(Anchorage, 40s.)

“Nine times out of 10, it was going to be a woman who was going to have to sacrifice her job, sacrifice her time to make sure that things kept running. And then by doing that, because you’ve taken time off… Maybe you had a really great job that would let you work from home. But if you didn’t, guess what? Now, you have a gap in your resume. Now, things don’t look so great. Why were you off for two years? It’s just another thing that makes us just a little bit less desirable to be hired.”(Anchorage, 40s.)

“The women that I worked with <in childcare–authors>, I would say <handled the pandemic times> poorly. Some of the women were suffering all the same stuff that I was suffering–overworked, underpaid, underappreciated by the system.”(Anchorage, 20s.)

“There was a great deal of time and energy and effort that went into going back teaching in person. There was a lot of intense just fear as providers. We didn’t want to mess up, ’Oh my God, I don’t want to get them <children–authors> sick.’ You had to wipe everything down… We had department meetings, or individual school meetings… We had committees and contingency plans. It was quite the system… That was a nightmare after a while. Really disruptive to this being in school, in person learning and staff members getting sick.”(Anchorage, 30s.)

“We were supposed to go back to in-person school in February. I remember people just being livid: ’Do you want to open schools and there’s no vaccines and everyone’s going to be sick?…’ I think that caused a lot of distrust in the community, especially for teachers. Our district here is huge. It’s one of the largest employers in the city and a lot of people no longer trusted or thought that the government or the school district cared about teachers’ safety and felt like we were just peons that were easily replaced…”(Anchorage, 30s.)

“Teachers were suddenly doing the role of not only a teacher, but also a kind of parent, mental health clinician, cook, providing all of these different things… And not just inundated with, you’re going to do five people’s jobs for the same amount of pay in all of these hours every week.”(Anchorage, 30s.)

“I would have arguments from families saying, ’I don’t want to bring my kid here because you require masks,’ and the parent of one of the kids in my class who’s a real COVID denier tried to tell us that requiring masks is child abuse… and then other families saying, ’You’re not doing enough to be COVID safe.’(Anchorage, 20s.)

“The most highly paid employee <in our childcare–authors> makes, I think, just under $20 an hour, and that is somebody who has been there for nearly 10 years… No benefits, no healthcare. Some holiday pay, depending on if you were regularly scheduled during a holiday… <Regarding the new hires–authors>, I have seen people with bachelor’s degrees, asking for 18 bucks an hour and being told, ’No, we can do 15.’ It’s pretty insulting… to see somebody with a bachelor’s degree, somebody who’s really capable, somebody who’s really passionate, and say, ’Yeah, this is what you’re worth to the higher-ups’.”(Anchorage, 20s.)

“I worked in childcare; I just left earlier this year.. I wasn’t too concerned about getting COVID … but just in that childcare environment, dealing with the emotional toll, dealing with everything there, the really toxic work environment that COVID had exacerbated,…–the underpayment, the long hours… I ended up working 10-hour days pretty regularly because of staffing shortage… You don’t go into childcare to get rich, you do it because you love it, and there’s a lot of turnover because the people who love it enough to pursue a degree in it, once they get that degree, are not going to be paid enough to stay in that..”(Anchorage, 20s.)

“Teachers are those first responders that see things. They get previews and hints of things that aren’t going well in a child’s life and in their home life, and they act as first responders… So many people quit that profession… because they became too much.”(Anchorage, 30s.)

“There are less, and less people inclined to fill those <female-dominated–authors> positions, so how do we make those career pathways desirable and meaningful again? I think it goes back to fair pay… It goes back to making supportive services like counseling and trauma-informed training more readily available…, and more just inspiration for them…”(Anchorage, 30s.)

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Absolon, Kathy. 2010. Indigenous Wholistic Theory: A Knowledge Set for Practice. First Peoples Child & Family Review 5: 74–87. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, Robert. 2008. Empowerment, Participation and Social Work. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Agloinga, Christina. 2021. Indigenous Women: Violence, Vulnerability, and Cultural Protective Factors. Ph.D. dissertation, Walden University, Minneapolis, MN, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Akakpo, Afi Florence, Koffi Sodokin, and Mawuli Kodjovi Couchoro. 2025. Social Capital, Gender-Based Resilience, and Well-Being among Urban and Rural Households in Togo. Journal of International Development 37: 251–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaska Criminal Justice Commission. 2022. Domestic Violence in Alaska. Anchorage: Alaska Criminal Justice Commission. Available online: https://www.ajc.state.ak.us/acjc/docs/rr/domestic_violence_in_alaska.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Alaska Department of Health. 2024. Statewide Suicide Prevention Council Annual Report 2024. Available online: https://health.alaska.gov/media/0umechcc/sspcannualreport2024.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Alaska Department of Labor and Workforce Development, Research and Analysis. 2025. Alaska Economic Trends (Monthly Economic Trends Magazine). July. Available online: https://live.laborstats.alaska.gov/trends-magazine/2025/July/the-cost-of-living-in-alaska (accessed on 2 August 2025).

- Alaska Housing Finance Corporation. 2018. 2018 Alaska Housing Assessment. Available online: https://www.ahfc.us/pros/energy/alaska-housing-assessment/2018-housing-assessment (accessed on 19 April 2025).

- Alon, Titan, Matthias Doepke, Jane Olmstead-Rumsey, and Michèle Tertilt. 2020. The Impact of the Coronavirus Pandemic on Gender Equality. Covid Economics: Vetted and Real-Time Papers 4: 62–85. [Google Scholar]

- Alsop, Ruth, Nina Heinsohn, and Abigail Somma. 2005. Measuring Empowerment: An Analytic Framework. In Power, Rights and Poverty: Concepts and Connections. Edited by Ruth Alsop. Washington: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- American Society of Civil Engineers, Alaska Section. 2025. 2025 Report Card for Alaska’s Infrastructure: Full Report. Available online: https://infrastructurereportcard.org/state-item/alaska/ (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Arctic Council. 2016. Arctic Resilience Report 2016. Available online: https://oaarchive.arctic-council.org/items/894931be-6903-4e89-a333-512851b64bc3 (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Arctic Mental Health Working Group. 2017. Alaska’s Mental Health Care Workforce Shortage; U.S. Arctic Research Commission. Available online: https://www.arctic.gov/uploads/assets/mental_health_workforce_10-2-17.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Arctic Resilience Forum. 2020. Arctic Resilience Forum 2020. Available online: https://sdwg.org/what-we-do/projects/arctic-resilience-forum-2020/ (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Arnalds, Ásdís Aðalbjörg, Ann-Zofie Duvander, Guðný Björk Eydal, and Ingólfur Vilhjálmur Gíslason. 2021. Constructing Parenthood in Times of Crisis. Journal of Family Studies 27: 420–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auðardóttir, Auður Magndís. 2022. From progressiveness to perfection: Mothers’ descriptions of their children in print media, 1970–1979 versus 2010–2019. European Journal of Cultural Studies 26: 212–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azcona, Ginette, Antra Bhatt, Jessamyn Encarnacion, Juncal Plazaola-Castaño, Papa Seck, Silke Staab, and Laura Turquet. 2021. From Insights to Action: Gender Equality in the Wake of COVID-19. United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women (UN Women). Available online: https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2020/09/gender-equality-in-the-wake-of-covid-19 (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Azcona, Ginette, Antra Bhatt, Sara E. Davies, Sophie Harman, Julia Smith, and ClareWenham. 2020. Spotlight on Gender, COVID-19 and the SDGs: Will the Pandemic Derail Hard-Won Progress on Gender Equality? United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women (UN Women). Available online: https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/105826/ (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Barkardóttir, Freyja. 2022. The Gendered Effects of the COVID-19 Crisis in Iceland. Stockholm: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. Available online: https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/stockholm/19732.pdf (accessed on 8 February 2025).

- Berry, Marie. 2022. Radicalizing Resilience: Mothering, Solidarity, and Interdependence among Women Survivors of War. Journal of International Relations and Development 25: 946–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branicki, Layla, Holly Birkett, and Bridgette Sullivan-Taylor. 2023. Gender and Resilience at Work: A Critical Introduction. Gender, Work & Organization 30: 129–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridges, Donna, Elizabeth Wulff, and Larissa Bamberry. 2023. Resilience for Gender Inclusion: Developing a Model for Women in Male-Dominated Occupations. Gender, Work & Organization 30: 263–79. [Google Scholar]

- Brysk, Alison. 2023. Pandemic Patriarchy: The Impact of a Global Health Crisis on Women’s Rights. In Rights at Stake and the COVID-19 Pandemic. London: Routledge, pp. 168–88. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Health Workforce, Health Resources & Services Administration. 2024. Designated Health Professional Shortage Areas Statistics: Designated HPSA Quarterly Summary, as of December 31, 2024; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Available online: https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/shortage-areas (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Charmaz, Kathy, and Linda Liska Belgrave. 2012. Qualitative Interviewing and Grounded Theory Analysis. In The SAGE Handbook of Interview Research: The Complexity of the Craft. Edited by Jaber Gubrium, James Holstein, Amir Marvasti and Karyn McKinney. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, Patricia Hill. 2019. Intersectionality as Critical Social Theory. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, David, and Lára Johannsdottir. 2021. Impacts, Systemic Risk and National Response Measures Concerning COVID-19—The Island Case Studies of Iceland and Greenland. Sustainability 13: 8470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornwall, Andrea. 2016. Women’s Empowerment: What Works? Journal of International Development 28: 342–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, Laura, Elin Alfredsson, and Elia Psouni. 2025. Mothers’ Experiences of Family Life during COVID-19: A Qualitative Comparison between Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Community, Work & Family 28: 254–71. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, Lyn, and Judith Brown. 2017. Feeling Rushed: Gendered Time Quality, Work Hours, Nonstandard Work Schedules, and Spousal Crossover. Journal of Marriage and Family 79: 225–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cueva, Katie, Elizabeth Rink, Josée Lavoie, Gwen Healey Akearok, Sean Guistini, Nicole Kanayurak, Jon Petter Stoor, and Christina Viskum Lytken Larsen. 2021. From Resilient to Thriving: Policy Recommendations to Support Health and Well-Being in the Arctic. Arctic 74: 550–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cueva, Katie, Malory Peterson, Ay’aqulluk Jim Chaliak, and Rebecca Ipiaqruk Young. 2024. A Qualitative Exploration of the Impacts of COVID-19 in Two Rural Southwestern Alaska Communities. International Journal of Circumpolar Health 83: 2313823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dean, Liz, Brendan Churchill, and Leah Ruppanner. 2021. The Mental Load: Building a Deeper Theoretical Understanding of How Cognitive and Emotional Labor Overload Women and Mothers. Community, Work & Family 25: 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Paz, Carmen, Miriam Muller, Ana Maria Muñoz Boudet, and Isis Gaddis. 2020. Gender Dimensions of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Washington: World Bank. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10986/33622 (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Ding, Regina, and Allison Williams. 2022. Places of Paid Work and Unpaid Work: Caregiving and Work-from-Home during COVID-19. The Canadian Geographer 66: 156–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunatchik, Allison, Kathleen Gerson, Jennifer Glass, Jerry Jacobs, and Haley S Stritzel. 2021. Gender, Parenting, and the Rise of Remote Work during the Pandemic: Implications for Domestic Inequality in the United States. Gender & Society 35: 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenbeck, Nikolett, José Antonio Pérez-Escobar, and David Carreno. 2021. Meaning-Centered Coping in the Era of COVID-19: Direct and Moderating Effects on Depression, Anxiety, and Stress. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 648383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erman, Alvina, Sophie Anne de Vries Robbé, Stephan Fabian Thies, Kayenat Kabir, and Mirai Maruo. 2021. Gender Dimensions of Disaster Risk and Resilience: Existing Evidence. Available online: https://srhr.dspace-express.com/server/api/core/bitstreams/bb8ad2f9-31c4-4568-8f53-ce30b15008bb/content (accessed on 18 January 2025).

- Ervin, Jennifer, Yamna Taouk, Ludmila Fleitas Alfonzo, Tessa Peasgood, and Tania King. 2022. Longitudinal Association between Informal Unpaid Caregiving and Mental Health amongst Working Age Adults in High-Income OECD Countries: A Systematic Review. EClinicalMedicine 53: 101589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faircloth, Charlotte. 2021. When Equal Partners Become Unequal Parents: Couple Relationships and Intensive Parenting Culture. Families, Relationships and Societies 10: 231–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faircloth, Charlotte. 2023. Intensive Parenting and the Expansion of Parenting. In Parenting Culture Studies. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, Sarah-Jane. 2016. Women and Education: Qualifications, Skills and Technology; Ottawa: Statistics Canada. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED585396.pdf (accessed on 28 January 2025).

- Flor, Luisa, Joseph Friedman, Cory Spencer, John Cagney, Alejandra Arrieta, Molly Herbert, and Emmanuela Gakidou. 2022. Quantifying the Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Gender Equality on Health, Social, and Economic Indicators: A Comprehensive Review of Data from March 2020 to September 2021. The Lancet 399: 2381–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, Geraldine, Virpi Timonen, Catherine Conlon, and Catherine Elliott O’Dare. 2021. Interviewing as a Vehicle for Theoretical Sampling in Grounded Theory. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 20: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankl, Viktor. 2006. Man’s Search for Meaning. Translated by IlseLasch. Boston: Beacon Press. First published 1946. [Google Scholar]

- Freysteinsdóttir, Freydís Jóna. 2022. Social Workers in Iceland in the Pandemic: Job Satisfaction, Stress, and Burnout. In Social Work—Perspectives on Leadership and Organisation. London: IntechOpen. [Google Scholar]

- Fried, Ruby, Micah Hahn, Lauren Gillott, Patricia Cochran, and Laura Eichelberger. 2022. Coping Strategies and Household Stress/Violence in Remote Alaska: A Longitudinal View across the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Circumpolar Health 81: 2149064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fried, Ruby, Micah Hahn, Patricia Cochran, and Laura Eichelberger. 2023. ‘Remoteness Was a Blessing, but Also a Potential Downfall’: Traditional/Subsistence and Store-Bought Food Access in Remote Alaska during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Public Health Nutrition 26: 1317–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, Gabriel, Joy Mapaye, Rebecca Van Wyck, Katie Cueva, Elizabeth H. Snyder, Jennifer Meyer, Jennifer Miller, and Thomas Hennessy. 2020. Needs Assessment Related to COVID-19 with Special Populations: Brief Report. Anchorage: University of Alaska Anchorage. Available online: https://scholarworks.alaska.edu/handle/11122/12951 (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- Giacci, Elena, Kee Straits, Amanda Gelman, Summer Miller-Walfish, Rosemary Iwuanyanwu, and Elizabeth Miller. 2021. Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence, Reproductive Coercion, and Reproductive Health among American Indian and Alaska Native Women: A Narrative Interview Study. Journal of Women’s Health 31: 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glomsrød, Solveig, Gérard Duhaime, and Iulie Aslaksen, eds. 2021. The Economy of the North—ECONOR 2020. Tromsø: Arctic Council Secretariat. Available online: https://www.ssb.no/en/natur-og-miljo/artikler-og-publikasjoner/the-economy-of-the-north-econor-2020 (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- Glomsrød, Solveig, Gérard Duhaime, and Iulie Aslaksen, eds. 2025. The Economy of the North—ECONOR 2025. Tromsø: Arctic Council Secretariat. Available online: https://www.ssb.no/en/natur-og-miljo/miljoregnskap/artikler/the-economy-of-the-north--econor-2025 (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Golubeva, Elena, Anastasia Emelyanova, Olga Kharkova, Arja Rautio, and Andrey Soloviev. 2022. Caregiving of Older Persons during the COVID-19 Pandemic in the Russian Arctic Province: Challenges and Practice. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodfield, Laura, Anissa Ozbek, Riya Bhushan, Sophie Rosenthal, Alicia Glassman, and Marya Rozanova-Smith. 2023. Understanding the COVID-19 Pandemic Gendered Policy Responses in Alaska through the Prism of a Holistic Wellness Concept. In Arctic Yearbook 2023. Edited by J. Spence, H. Exner-Pirot and A. Petrov. Akureyri: Northern Research Forum & University of the Arctic. [Google Scholar]

- Goyal, Rita, Nada Kakabadse, Andrew Kakabadse, and Danielle Talbot. 2023. Female Board Directors’ Resilience against Gender Discrimination. Gender, Work & Organization 30: 197–222. [Google Scholar]

- Graybill, Jessica, and Andrey Petrov. 2020. Arctic Sustainability, Key Methodologies and Knowledge Domains. In Arctic Sustainability, Key Methodologies and Knowledge Domains. Edited by Andrey Petrov. London: Routledge, pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Hagler, Matthew, Elizabeth Taylor, Michelle Wright, and Katie Querna. 2025. Psychosocial Strengths and Resilience among Sexual and Gender Minority Youth Experiencing Homelessness: A Scoping Review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 26: 327–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamby, Sherry, John Grych, and Victoria Banyard. 2018. Resilience Portfolios and Poly-Strengths: Identifying Protective Factors Associated with Thriving after Adversity. Psychology of Violence 8: 172–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haney, Timothy, and Kristen Barber. 2022. The Extreme Gendering of COVID−19: Household Tasks and Division of Labour Satisfaction during the Pandemic. Canadian Review of Sociology 59: 26–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hank, Karsten, and Anja Steinbach. 2021. The Virus Changed Everything, Didn’t It? Couples’ Division of Housework and Childcare before and during the Corona Crisis. Journal of Family Research 33: 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankivsky, Olena. 2014. Intersectionality 101. Vancouver: Institute for Intersectionality Research and Policy, Simon Fraser University. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, Angie, Emily Gagnon, Suna Eryigit-Madzwamuse, Josh Cameron, Kay Aranda, Anne Rathbone, and Becky Heaver. 2016. Uniting Resilience Research and Practice with an Inequalities Approach. SAGE Open 6: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haupt, Marlene, and Viola Lind. 2021. Gender Crisis, or Not? A Comparative Analysis of the Impact on Gender Equality in Sweden and Germany Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic. In Social Policy Review 33. Bristol: Policy Press, chap. 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, Sharon. 1996. The Cultural Contradictions of Motherhood. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heintz, James. 2021. Stalled Progress: Why Labour Markets Are Failing Women. In Women’s Economic Empowerment: Insights from Africa and South Asia. Edited by Kate Grantham, Gillian Dowie and Arjan de Haan. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 51–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helgøy, Anna, and Ana Catalano Weeks. 2025. Crowded Out: The Influence of Mental Load Priming on Intentions to Participate in Public Life. British Journal of Political Science 55: e29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, Kimberly, and Christopher Greig. 2020. Motherhood and Mothering during COVID-19: A Gendered Intersectional Analysis of Caregiving during the Global Pandemic within a Canadian Context. Journal of Mother Studies 5: 1. [Google Scholar]

- Hjálmsdóttir, Andrea, and Guðbjörg Linda Rafnsdóttir. 2022. Gender, Doctorate Holders, Career Path, and Work–Life Balance Within and Outside of Academia. Journal of Sociology 60: 192–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjálmsdóttir, Andrea, and Valgerður Bjarnadóttir. 2021. ‘I Have Turned into a Foreman Here at Home’: Families and Work–Life Balance in Times of COVID-19 in a Gender Equality Paradise. Gender, Work & Organization 28: 268–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjorthol, Randi, and Aslak Fyhri. 2009. Do Organized Leisure Activities for Children Encourage Car-Use? Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 43: 209–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC). 2022. Circumpolar Inuit Protocols for Equitable and Ethical Engagement. Anchorage: ICC. Available online: https://www.inuitcircumpolar.com/project/circumpolar-inuit-protocols-for-equitable-and-ethical-engagement/ (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Johnson, Ingrid. 2021. 2020 Statewide Alaska Victimization Survey: Final Report; Anchorage: University of Alaska Anchorage Justice Center. Available online: https://scholarworks.alaska.edu/handle/11122/12259 (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Johnson, Noor, Kaare Sikuaq Erickson, Daniel Ferguson, Mary Beth Jäger, Lydia Jennings, Amy Juan, Shawna Larson, Wendy K’ah Skaahluwaa Smythe, Colleen Strawhacker, Althea Walker, and et al. 2022. The Impact of COVID-19 on Food Access for Alaska Natives in 2020. Washington: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juncos, Ana, and Philippe Bourbeau. 2022. Resilience, Gender, and Conflict: Thinking about Resilience in a Multidimensional Way. Journal of International Relations and Development 25: 861–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabeer, Naila. 1999. Resources, Agency, Achievements: Reflections on the Measurement of Women’s Empowerment. Development and Change 30: 435–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabeer, Naila, Shahra Razavi, and Yana van der Meulen Rodgers. 2021. Feminist Economic Perspectives on the COVID-19 Pandemic. Feminist Economics 27: 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaijser, Anna, and Annica Kronsell. 2014. Climate Change through the Lens of Intersectionality. Environmental Politics 23: 417–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsdóttir, Anna, and Hanne Marit Dalen. 2025. Gender Distribution in the Nordic Primary Industry with a Focus on the Blue Economy. In The Economy of the North—ECONOR 2025. Edited by Sverre Glomsrød, Gérard Duhaime and Iulie Aslaksen. Tromsø: Arctic Council Secretariat, pp. 129–131. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsdóttir, Anna, and Hjördís Guðmundsdóttir. 2024. Ensuring Gender Equality in Nordic Blue Economy: Results from the Salmon and Equality Project. Copenhagen: Nordic Council of Ministers. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsdóttir, Anna, Jean-Michel Huctin, Jeanne-Marie Gherardi, Tanguy Sandré, and Jean-Paul Vanderlinden. 2023. Working with and for Arctic Communities on Resilience Enhancement. Arctic Yearbook. Available online: https://arcticyearbook.com/arctic-yearbook/2023/2023-scholarly-papers/495-working-with-and-for-arctic-communities-on-resilience-enhancement (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- Kovach, Margaret. 2021. Indigenous Methodologies: Characteristics, Conversations, and Contexts. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kwan, Vivien, Johnson Chun-Sing Cheung, and Jenny Wai-Chi Kong. 2020. Women’s Leadership in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Political Insight 11: 13–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landry, Bart, ed. 2007. Race, Gender and Class: Theory and Methods of Analysis, 1st ed. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, Joan Nymand, and Gail Fondahl. 2014. Arctic Human Development Report II: Regional Processes and Global Linkages. Copenhagen: Nordic Council of Ministers. [Google Scholar]

- Leap, Braden, Marybeth Stalp, and Kimberly Kelly. 2023. Reorganizations of Gendered Labor during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Review and Suggestions for Further Research. Sociological Inquiry 93: 179–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Masson, Virginie. 2015. BRACED Working Paper: Gender and Resilience. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemieux, Thomas, Kevin Milligan, Tammy Schirle, and Mikal Skuterud. 2020. Initial Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Canadian Labour Market. Canadian Public Policy 46: S55–S65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, Diane, Jolie Biess, Alexandra Baum, Nancy Pindus, and Brian Murray. 2017. Housing Needs of American Indians and Alaska Natives Living in Urban Areas: A Report from the Assessment of American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian Housing Needs. Washington: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Available online: https://www.urban.org/research/publication/housing-needs-american-indians-and-alaska-natives-tribal-areas (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- Lowe, Marie, and Suzanne Sharp. 2021. Gendering Human Capital Development in Western Alaska. Economic Anthropology 8: 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundgren, Gunnel, Maria Bengtsson, and Anna Liebenhagen. 2023. Swedish Emergency Nurses’ Experiences of the Preconditions for the Safe Collection of Blood Culture in the Emergency Department during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nursing Open 10: 1619–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnusson, Charlotta. 2019. Flexible Time—But Is the Time Owned? Family Friendly and Family Unfriendly Work Arrangements, Occupational Gender Composition and Wages: A Test of the Mother-Friendly Job Hypothesis in Sweden. Community, Work & Family 24: 291–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markova, V. N., K. Alekseeva, A. N. Neustroeva, and E. V. Potravnaya. 2021. Analysis and Forecast of the Poverty Rate in the Arctic Zone of the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia). Studies on Russian Economic Development 32: 415–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, Amy, Alice Woolverton, and Cynthia García Coll. 2020. Risk and Resilience in Minority Youth Populations. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 16: 151–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, Karen, and Booran Mirraboopa. 2003. Ways of Knowing, Being, and Doing: A Theoretical Framework and Methods for Indigenous and Indigenist Research. Journal of Australian Studies 27: 203–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, Ron. 2012. Regional Economic Resilience, Hysteresis and Recessionary Shocks. Journal of Economic Geography 12: 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Men, Fei, and Valerie Tarasuk. 2021. Food Insecurity amid the COVID-19 Pandemic: Food Charity, Government Assistance, and Employment. Canadian Public Policy 47: 202–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meter, Ken, and Megan Phillips Goldenberg. 2014. Building Food Security in Alaska. Minneapolis: Crossroads Resource Center. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Ilan. 2015. Resilience in the Study of Minority Stress and Health of Sexual and Gender Minorities. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity 2: 209–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffitt, Pertice, Wendy Aujla, Crystal J. Giesbrecht, Isabel Grant, and Anna-Lee Straatman. 2022. Intimate Partner Violence and COVID-19 in Rural, Remote, and Northern Canada: Relationship, Vulnerability and Risk. Journal of Family Violence 37: 775–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadkarni, Ashwini, and Jhilam Biswas. 2022. Gender Disparity in Cognitive Load and Emotional Labor—Threats to Women Physician Burnout. JAMA Psychiatry 79: 745–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, Deepa, ed. 2002. Empowerment and Poverty Reduction: A Sourcebook. Washington: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, Katie, Alexandra Jackson, Cassandra Nguyen, Carolyn Noonan, Clemma Muller, Richard MacLehose, Spero Manson, Denise Dillard, and Dedra Buchwald. 2024. Food Insecurity in Urban American Indian and Alaska Native Populations during the COVID-19 Pandemic. BMC Public Health 24: 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesset, Merete Berg, Camilla Buch Gudde, Gro Elisabet Mentzoni, and Tom Palmstierna. 2021. Intimate Partner Violence during COVID-19 Lockdown in Norway: The Increase of Police Reports. BMC Public Health 21: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicewonger, Todd, Lisa McNair, and Stacey Fritz. 2021. COVID-19 and Housing Security in Remote Alaska Native Communities: An Annotated Bibliography. Edited by Lisa D. McNair, Todd E. Nicewonger and Stacey Fritz. Washington: Department of the Interior, Bureau of Indian Affairs. Available online: https://pressbooks.lib.vt.edu/alaskanative/ (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- Novoa, Consuelo, Félix Cova, Gabriela Nazar, Karen Oliva, and Pablo Vergara-Barra. 2022. Intensive Parenting: The Risks of Overdemanding. Trends in Psychology 33: 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nylin, Anna-Karin, Stefanie Mollborn, and Sunnee Billingsley. 2025. Does Intensive Parenting Come at the Expense of Parents’ Health? Evidence from Sweden. Stockholm Research Reports in Demography. Stockholm: Stockholm University. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oddsdóttir, Embla Eir, and Hjalti Ómar Ágústsson, eds. 2021. Pan-Arctic Report: Gender Equality in the Arctic. Akureyri: Iceland’s Arctic Council Chairmanship, Arctic Council Sustainable Development Working Group, Icelandic Arctic Cooperation Network, Icelandic Directorate for Equality, Stefansson Arctic Institute. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. 2021. Caregiving in Crisis: Gender Inequality in Paid and Unpaid Work during COVID-19. OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19). Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office of the Governor, State of Alaska. 2020. COVID-19 Health Mandates. In State of Alaska; March 28. Available online: https://gov.alaska.gov/home/covid19-healthmandates/ (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Olsen, Bjørn, Andrey Mineev, Erlend Bullvåg, Sissel Ovesen, Alexandra Middleton, Elena Hoff, and Andrey Bryksenkov. 2022. Business Index North: A Periodic Report with Insights to Business Activity and Opportunities in the Arctic: Socio-Economic Resilience in the Barents Arctic. Bodø: Nord University Business School. Available online: https://businessindexnorth.com/sites/b/businessindexnorth.com/files/bin_rapport-2022-v2_lq_1.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Otonkorpi-Lehtoranta, Katri, Milla Salin, Mia Hakovirta, and Anniina Kaittila. 2021. Gendering Boundary Work: Experiences of Work–Family Practices among Finnish Working Parents during COVID-19 Lockdown. Gender, Work & Organization 29: 1952–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Crystal. 2016. Meaning Making in the Context of Disasters. Journal of Clinical Psychology 72: 1234–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, Charlie, Sam Scott, and Alistair Geddes. 2019. Snowball Sampling. In SAGE Research Methods Foundations. London: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, David, Jennifer A. Meyer, and Marissa Abram. 2023. National Data and the Applicability to Understanding Rural and Remote Substance Use. Journal of Primary Prevention 44: 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, Andrey, Mark Welford, Nikolay Golosov, John DeGroote, Michele Devlin, Tatiana Degai, and Alexander Savelyev. 2021. The ‘Second Wave’ of the COVID-19 Pandemic in the Arctic: Regional and Temporal Dynamics. International Journal of Circumpolar Health 80: 1925446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrov, Andrey, Shauna BurnSilver, Stuart Chapin, III, Gail Fondahl, Jessica Graybill, Kathrin Keil, Annika Nilsson, Rudolf Riedlsperger, and PeterSchweitzer. 2016. Arctic Sustainability Research: Toward a New Agenda. Polar Geography 39: 165–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petts, Richard, Daniel Carlson, and Joanna Pepin. 2021. A Gendered Pandemic: Childcare, Homeschooling, and Parents’ Employment during COVID-19. Gender, Work & Organization 28: 515–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillipps, Breanna, Kelly Skinner, Barbara Parker, and Hannah Tait Neufield. 2022. An Intersectionality-Based Policy Analysis Examining the Complexities of Access to Wild Game and Fish for Urban Indigenous Women in Northwestern Ontario. Frontiers in Science and Environmental Communication 6: 762083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pindus, Nancy, Thomas Kingsley, Jennifer Biess, Diane Levy, Jasmine Simington, and Hayes Christopher. 2017. Housing Needs of American Indians and Alaska Natives in Tribal Areas: A Report from the Assessment of American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian Housing Needs; Washington: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research. Available online: https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/HNAIHousingNeeds.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2025).

- Piovani, Chiara, and Nursel Aydiner-Avsar. 2021. Work Time Matters for Mental Health: A Gender Analysis of Paid and Unpaid Labor in the United States. Review of Radical Political Economics 53: 579–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prior, Tahnee Lisa, and Malgorzata Smieszek. 2023. Women of the Arctic. Polar Record 59: e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich-Stiebert, Natascha, Lara Froehlich, and Jan Voltmer. 2023. Gendered Mental Labor: A Systematic Literature Review on the Cognitive Dimension of Unpaid Work within the Household and Childcare. Sex Roles 88: 475–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, Jennifer, and Lindsay Tedds, eds. 2022. Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Women in Canada. Ottawa: Royal Society of Canada. Available online: https://rsc-src.ca/sites/default/files/pdf/Women%20PB_EN.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Rothe, Delf. 2017. Gendering Resilience: Myths and Stereotypes in the Discourse on Climate-Induced Migration. Global Policy 8: 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozanova-Smith, Marya, and Andrey Petrov. 2025. Arctic economies from a gender perspective: Persistent, recent, and emerging trends. In The Economy of the North—ECONOR 2025. Edited by Solveig Glomsrød, Gérard Duhaime and Iulie Aslaksen. Tromsø: Arctic Council Secretariat, pp. 125–29. [Google Scholar]

- Rozanova-Smith, Marya, Andrey Petrov, and Charlene Apok. 2023a. Gendered Impacts of COVID-19: Designing a COVID-19 Gender Impacts and Policy Responses Indicators Framework for Arctic Communities. In Arctic Yearbook 2023: Arctic Pandemics (Special Issue). Edited by James Spence, Heather Exner-Pirot and Andrey Petrov. Akureyri: Northern Research Forum & University of the Arctic. Available online: https://arcticyearbook.com/arctic-yearbook/2023-special-issue (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Rozanova-Smith, Marya, Andrey Petrov, Korkina Williams Varvara, Absalonsen Joanna, Alty Rebecca, Arnfjord Steven, Apok Charlene, Biscaye Elizabeth (Sabet), Black Jessica, Carothers Courtney, and et al. 2021. Gender Empowerment and Fate Control. In Gender Equality in the Arctic. Edited by Embla Eir Oddsdóttir and Hjalti Ómar Ágústsson. Akureyri: Iceland’s Arctic Council Chairmanship, Arctic Council Sustainable Development Working Group, Icelandic Arctic Cooperation Network, Icelandic Directorate for Equality, Stefansson Arctic Institute, pp. 224–67. Available online: https://arcticgenderequality.network/phase-3/pan-arctic-report (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Rozanova-Smith, Marya, Charlene Apok, and Andrey Petrov. 2025a. “I Think Even in Challenging Times We Can Still Be Uplifting”: Indigenous Women’s Experiences of Resilience to the COVID-19 Pandemic in Alaska. Societies 15: 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozanova-Smith, Marya, Embla Eir Oddsdóttir, and Andrey N. Petrov. 2025b. ‘I Feel Like the Most Important Thing Is to Ensure That Women Feel Included…’: Immigrant Women’s Experiences of Integration and Gender Equality in Iceland during Times of Crisis. Sustainability 17: 4069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozanova-Smith, Marya, Laura Goodfield, Riya Bhushan, Anissa Ozbek, Sophie Rosenthal, and Harshit Aggarwal. 2023b. The COVID-19 Gender-Responsive Policies in the Arctic (2020–2022). Arctic Data Center. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, Mou Rani. 2021. Labor Market and Unpaid Works Implications of COVID-19 for Bangladeshi Women. Gender, Work & Organization 28: 597–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, Katherine. 2024. Work in Progress: Women in Canada’s Changing Post-Pandemic Labour Market. Bumpy Ride Series, Spring 2024 Update. Ottawa: Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. Available online: https://policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/National%20Office/2024/05/CCPA%20report%20Work%20in%20Progress%20EMBARGOED%20TILL%20May%208%202024.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Seedat, Soraya, and Marta Rondon. 2021. Women’s Wellbeing and the Burden of Unpaid Work. BMJ 374: n1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silonsaari, Jonne, Mikko Simula, and Marco te Brömmelstroet. 2024. From Intensive Car-Parenting to Enabling Childhood Velonomy? Explaining Parents’ Representations of Children’s Leisure Mobilities. Mobilities 19: 116–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Símonardóttir, Sunna. 2016. Constructing the ‘Attached Mother’ in the ‘World’s Most Feminist Country. Women’s Studies International Forum 56: 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Símonardóttir, Sunna, and Ásdís Arnalds. 2024. Excluding the Involved Father: Having a Child During the COVID Pandemic in Iceland. NORA—Nordic Journal of Feminist and Gender Research 32: 363–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slingsby, Danielle. 2020. Kawerak, NSEDC and NSHC Provide Donation to City of Nome to Expedite Processing of Sexual Assault Backlog Cases. Kawerak. September 16. Available online: https://kawerak.org/kawerak-nsedc-and-nshc-provide-donation-to-city-of-nome-to-expedite-processing-of-sexual-assault-backlog-cases/ (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Smith, Jacqueline. 2023. Thrivance During the Pandemic: Urban Indigenous Women and Mental Wellness. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Liris, Mark Christopher, and Michelle Leach. 2023. The Impacts of COVID-19 on Yukon’s Frontline Healthcare Workers. In Arctic Yearbook 2023: Arctic Pandemics (Special Issue). Edited by James Spence, Heather Exner-Pirot and Andrey Petrov. Akureyri: Northern Research Forum & University of the Arctic. Available online: https://arcticyearbook.com/arctic-yearbook/2023-special-issue/2023-special-scholarly-papers/471-the-impacts-of-covid-19-on-yukon-s-frontline-healthcare-workers (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Smyth, Ines, and Caroline Sweetman. 2015. Introduction: Gender and Resilience. Gender & Development 23: 405–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teel, Sara. 2022. The Child Care Shortage. Alaska Economic Trends 42: 6, Alaska Department of Labor and Workforce Development. Available online: https://labor.alaska.gov/trends/trends2022.htm (accessed on 2 April 2025).

- Thorsteinsen, Kjærsti, Elizabeth Parks-Stamm, Marie Kvalø, Marte Olsen, and Sarah Martiny. 2022. Mothers’ Domestic Responsibilities and Well-Being During the COVID-19 Lockdown: The Moderating Role of Gender Essentialist Beliefs About Parenthood. Sex Roles 87: 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, Sweta, Andrey Petrov, Nikolay Golosov, Michele Devlin, Mark Welford, John DeGroote, Tatiana Degai, and Stanislav Ksenofontov. 2024. Regional Geographies and Public Health Lessons of the COVID-19 Pandemic in the Arctic. Frontiers in Public Health 11: 1324105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorova, Irina, Liesemarie Albers, Nicole Aronson, Adriana Baban, Yael Benyamini, Sabrina Cipolletta, and Asya Zlatarska. 2021. ‘What I Thought Was So Important Isn’t Really That Important’: International Perspectives on Making Meaning During the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine 9: 830–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trudell, AnnaLise, and Erin Whitmore. 2020. Pandemic Meets Pandemic: Understanding the Impacts of COVID-19 on Gender-Based Violence Services and Survivors in Canada. Ottawa, ON: Ending Violence Association of Canada. Available online: https://endingviolencecanada.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/FINAL.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Tyner, Katie, and Farida Jalalzai. 2022. Women Prime Ministers and COVID-19: Within-Case Examinations of New Zealand and Iceland. Politics & Policy 50: 1076–95. [Google Scholar]

- University of Alaska Fairbanks. 2022. Alaska Food Policy Council, and 2022 Governor’s Task Force on Food Security and Independence. Alaska Food Security and Independence Task Force 2022 Report. Available online: www.alaskafoodsystems.com (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2020. QuickFacts: Anchorage Municipality, Alaska. Available online: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/anchoragemunicipalityalaska/POP010220 (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2022. QuickFacts: Nome Census Area and Anchorage Municipality, Alaska. Available online: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/nomecensusareaalaska,anchoragemunicipalityalaska/POP010220 (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation, and Alaska Chamber. 2021. Untapped Potential: How Childcare Impacts Alaska’s Workforce Productivity and the State Economy. Available online: https://www.uschamberfoundation.org/sites/default/files/EarlyEd_ALASKA_2021_DIGITAL.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- van Doren, Taylor, Deborah Zajdman, Ryan A. Brown, Priya Gandhi, Ron Heintz, Lisa Busch, Callie Simmons, and Raymond Paddock. 2023. Risk Perception, Adaptation, and Resilience During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Southeast Alaska Natives. Social Science & Medicine 317: 115609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Doren, Taylor, Ryan Brown, Guangqing Chi, Patricia Cochran, Katie Cueva, Laura Eichelberger, Ruby Fried, Stacey Fritz, Micah Hahn, Ron Heintz, and et al. 2024. Beyond COVID: Towards a Transdisciplinary Synthesis for Understanding Responses and Developing Pandemic Preparedness in Alaska. International Journal of Circumpolar Health 83: 2404273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venuleo, Claudia, Tiziana Marinaci, Alessandro Gennaro, and Arianna Palmieri. 2020. The Meaning of Living in the Time of COVID-19: A Large Sample Narrative Inquiry. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 577077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Violence Policy Center. 2021. When Men Murder Women. Washington: Violence Policy Center. Available online: https://vpc.org/when-men-murder-women/ (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Walker, Brian, and David Salt. 2012. Resilience Thinking: Sustaining Ecosystems and People in a Changing World. Washington: Island Press. [Google Scholar]

- Weeks, Ana Catalano. 2024. The Political Consequences of the Mental Load. Working Paper. Available online: https://anacweeks.github.io/assets/pdf/Weeks_ML_July2024.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2025).

- Weinstock, Madison, Sara Moyer, Nancy Jallo, Amy Rider, and Patricia Kinser. 2023. Perinatal Meaning-Making and Meaning-Focused Coping in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology 42: 896–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiebold, Karinne. 2021. The Gender Wage Gap. Alaska Economic Trends 41: 11. Available online: https://labor.alaska.gov/trends/trends2021.htm (accessed on 22 March 2025).

- Wiebold, Karinne. 2024. Alaska Women in Construction. In Alaska Economic Trends; June. Available online: https://live.laborstats.alaska.gov/trends-articles/2024/06/alaska-women-in-construction (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Women and Gender Equality Canada. 2021. 2021 Transition Binder Two: Gender Equality in Canada. Ottawa: Government of Canada. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/women-gender-equality/transparency/ministerial-transition-binder/2021-transition-binder-two/gender-equality-canada.html (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Yang, Mark. 2020. Resilience and Meaning-Making amid the COVID-19 Epidemic in China. Journal of Humanistic Psychology 60: 662–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamberlan, Anna, Filippo Gioachin, and Davide Gritti. 2021. Work Less, Help Out More? The Persistence of Gender Inequality in Housework and Childcare during UK COVID-19. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 100: 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Yingqin, and Geoff Walsham. 2021. Inequality of What? An Intersectional Approach to Digital Inequality under COVID-19. Information and Organization 31: 100341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Social | Economic | |

|---|---|---|

| Strengths | Capacity to redesign women’s social support networks Commitment to serving as community caregivers and addressing community needs Willingness to serve in mentorship roles Capacity for critical reflection on personal and social values and the ability to foster change Ability to reconfigure household gender roles Capacity to critically examine the supermom syndrome | Ability to productively use flexible and remote work schedules Ability to use education opportunities as a means of economic empowerment and professional growth Capacity to critically reflect on workplace inequalities and challenge conventional norms Capacity to transition into new and male-dominated professions Competence in versatile leadership during crisis |

| Constraints | Re-emergence of traditional gender roles in the household Intensified gendered division of parenting Housing crisis and increase in domestic violence Increased burden of (parents’) guilt Disrupted social support networks, political polarization, and family divides over pandemic measures Women’s legitimate interests receive lower priority | Heightened levels of unpaid domestic labor Challenges of remote work, the gendered digital divide, and digital inequalities Widened gender wage and unemployment gaps Lowered “glass ceilings” Intensified motherhood penalty Challenges in re-entering the workforce and pursuing careers Unfolded crisis in female-dominated occupations |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rozanova-Smith, M.; Petrov, A.N. “I Feel Like a Lot of Times Women Are the Ones Who Are Problem-Solving for All the People That They Know”: The Gendered Impacts of the Pandemic on Women in Alaska. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 498. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080498

Rozanova-Smith M, Petrov AN. “I Feel Like a Lot of Times Women Are the Ones Who Are Problem-Solving for All the People That They Know”: The Gendered Impacts of the Pandemic on Women in Alaska. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(8):498. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080498

Chicago/Turabian StyleRozanova-Smith, Marya, and Andrey N. Petrov. 2025. "“I Feel Like a Lot of Times Women Are the Ones Who Are Problem-Solving for All the People That They Know”: The Gendered Impacts of the Pandemic on Women in Alaska" Social Sciences 14, no. 8: 498. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080498

APA StyleRozanova-Smith, M., & Petrov, A. N. (2025). “I Feel Like a Lot of Times Women Are the Ones Who Are Problem-Solving for All the People That They Know”: The Gendered Impacts of the Pandemic on Women in Alaska. Social Sciences, 14(8), 498. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080498