Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Positive Psychology Interventions in Workplace Settings

Abstract

1. Introduction

Aim of This Research

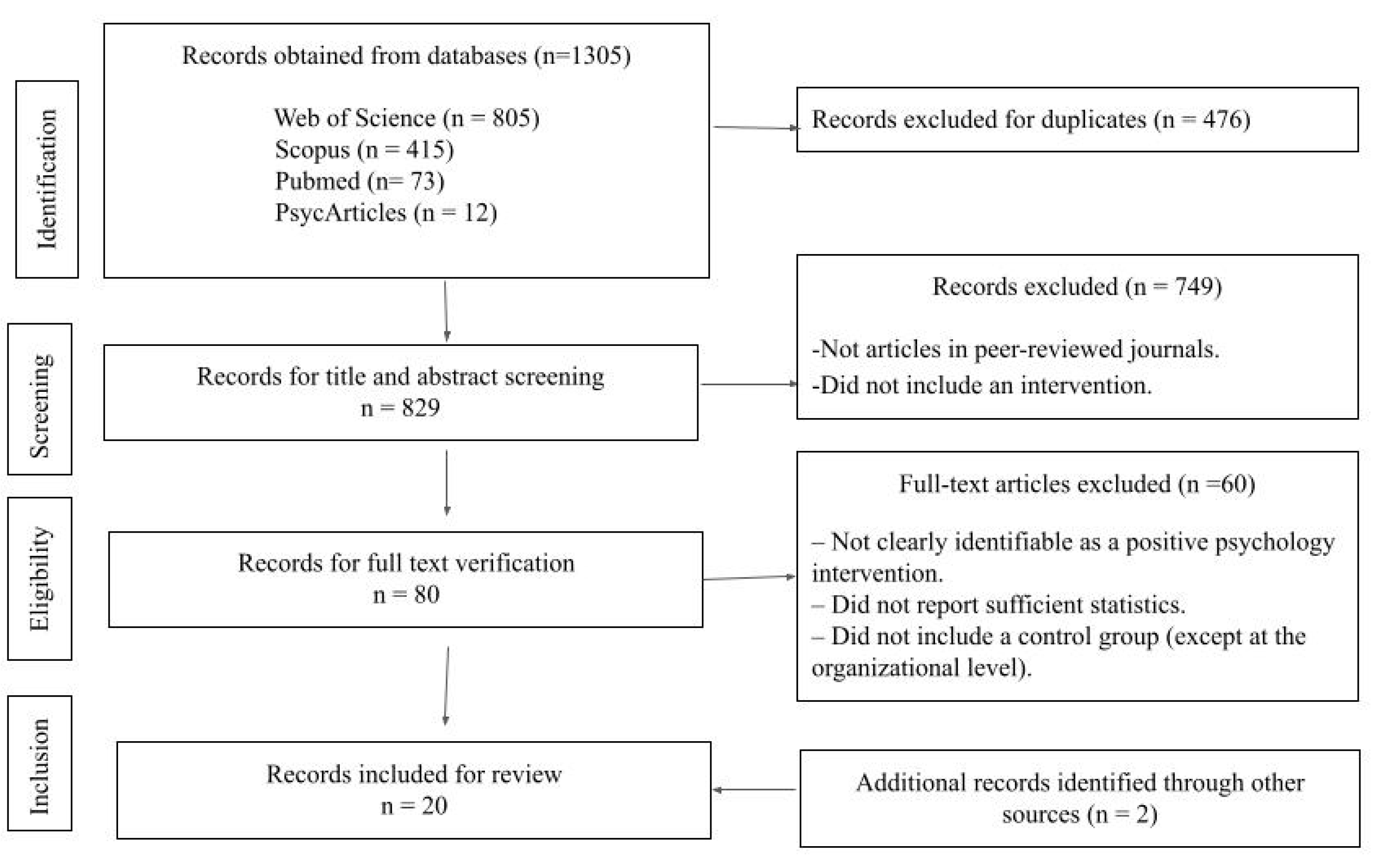

2. Material and Method

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Selection of Studies

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Well-Being Component

2.5. Performance Component

2.6. Sensitivity Analysis and Study Quality Assessment

2.7. Meta-Analysis and Heterogeneity Assessment

2.8. Moderator Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographics and Study Characteristics

3.2. Between- and Within-Group Comparisons

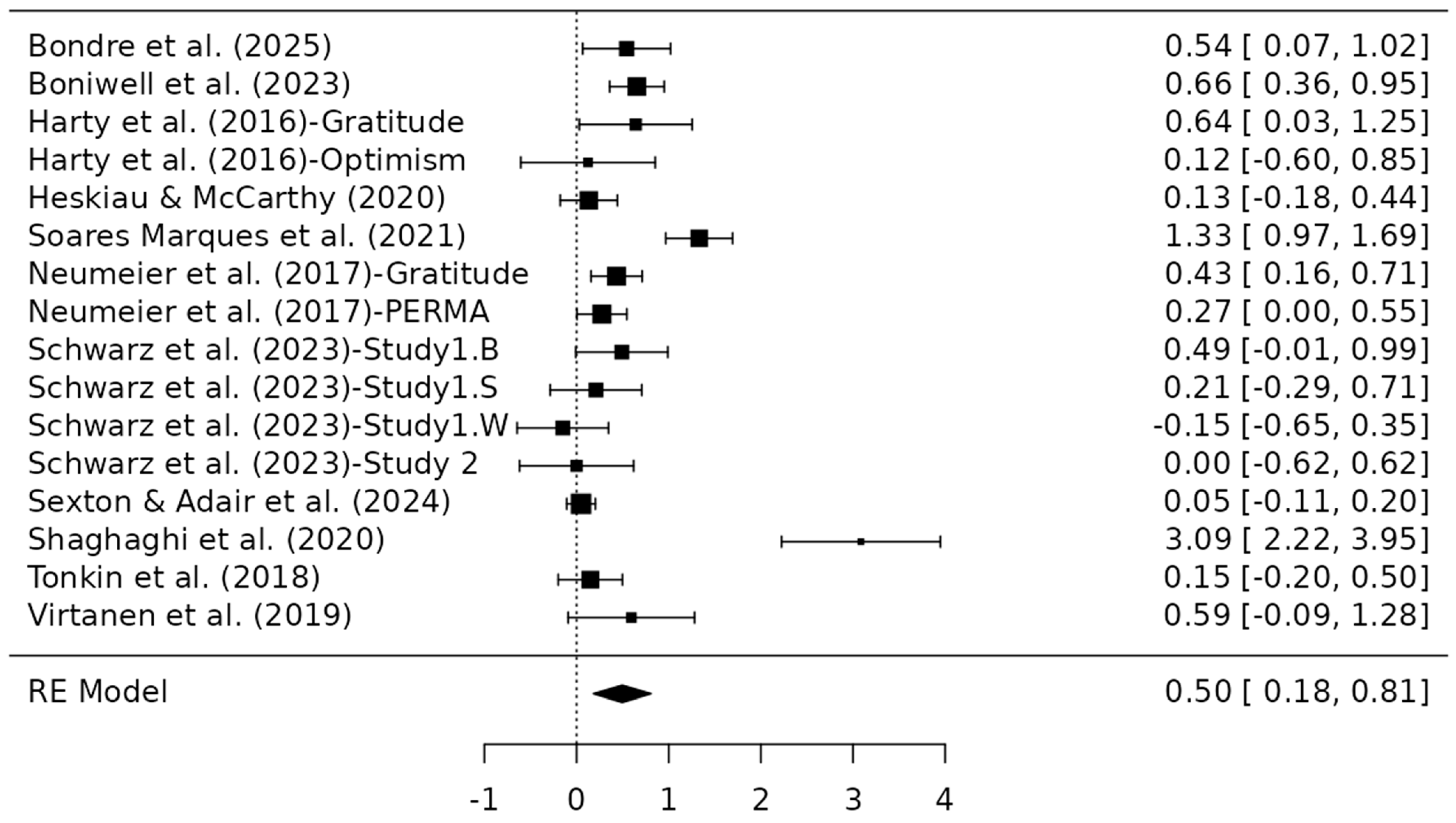

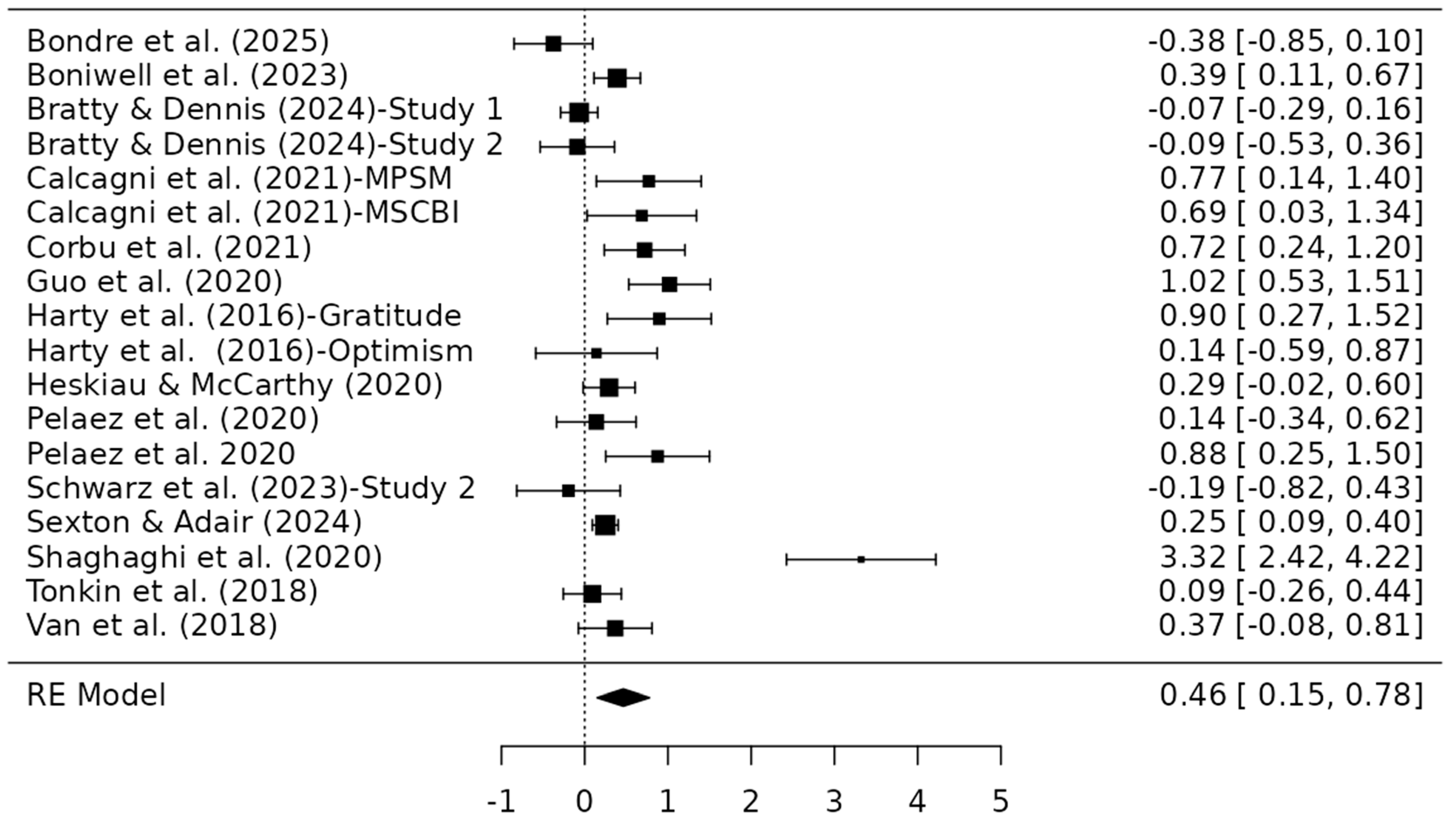

3.3. Effectiveness of PPIs on Subjective and Psychological Well-Being

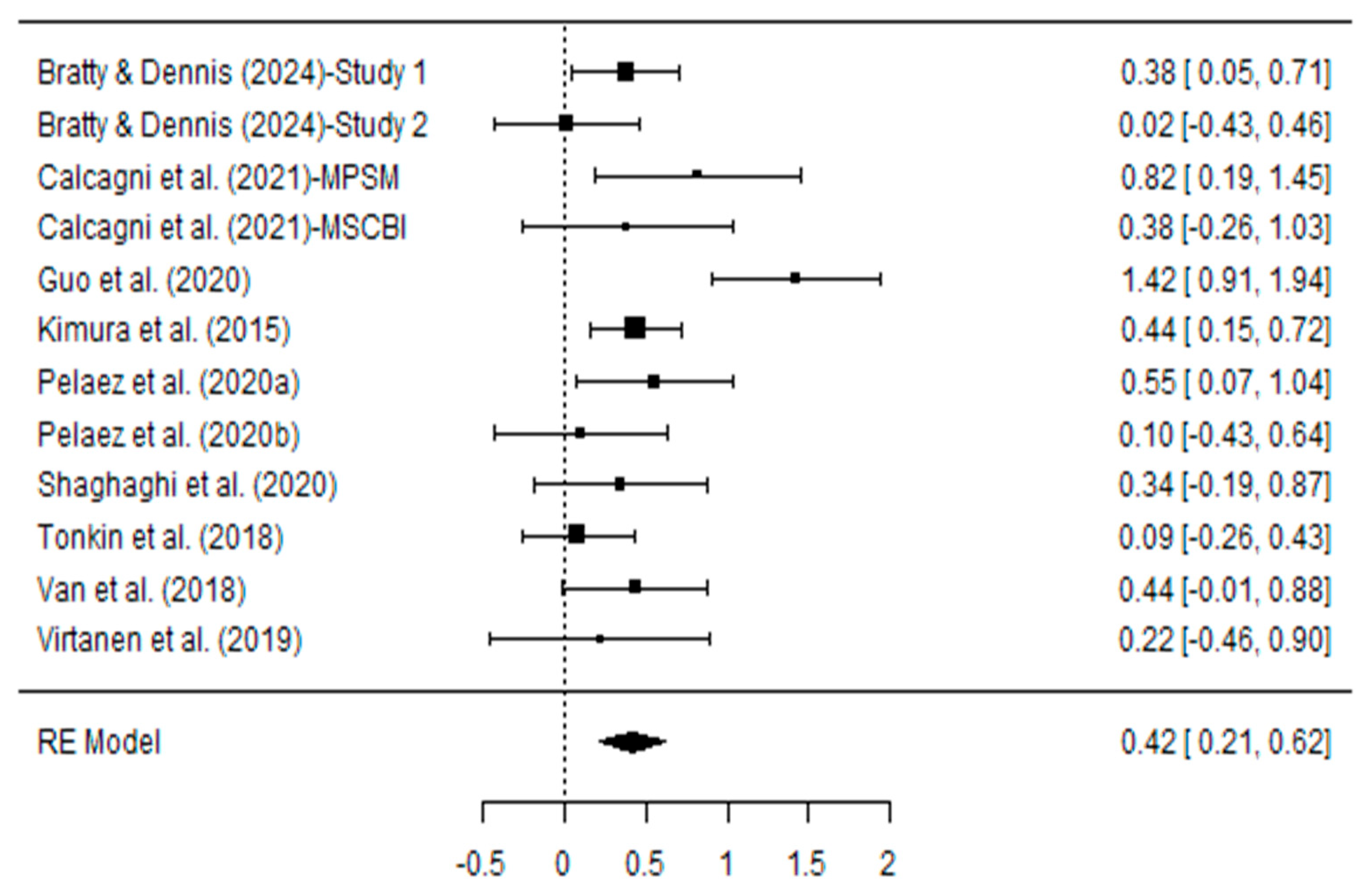

3.4. Effectiveness of PPIs on Performance

3.5. Effectiveness of PPI on Moderating Variables

3.6. Effectiveness of PPIs Follow-Up

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Akhtar, Sadaf, and Jane Barlow. 2018. Forgiveness therapy for the promotion of mental well-being: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma Violence Abuse 19: 107–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskin, Thomas, and Robert Enright. 2004. Intervention studies on forgiveness: A meta-analysis. Journal of Counseling & Development 82: 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastounis, Anastasios, Patrick Callaghan, Anirban Banerjee, and Maria Michail. 2016. The effectiveness of the Penn resiliency program (PRP) and its adapted versions in reducing depression and anxiety and improving explanatory style: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Adolescence 52: 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begg, Colin B., and Madhuchhanda Mazumdar. 1994. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 50: 1088–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolier, Linda, Merel Haverman, Gerben J. Westerhof, Heleen Riper, Filip Smit, and Ernst Bohlmejier. 2013. Positive psychology interventions: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. BMC Public Health 13: 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bommer, William H., Jonathan L. Johnson, Gregory A. Rich, Philip M. Podsakoff, and Scott B. MacKenzie. 1995. On the interchangeability of objective and subjective measures of employee performance: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology 48: 587–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondre, Ameya P., Spriha Singh, Abhishek Singh, Aashish Ranjan, Azaz Khan, Lochan Sharma, Dinesh Bari, G. Sai Teja, Laxmi Verma, Mehak Jolly, and et al. 2025. Evaluation of a positive psychological intervention to reduce work stress among rural community health workers in India: Results from a randomized pilot study. Journal of Happiness Studies 26: 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boniwell, Ilona, Evgeny Osin, Larissa Kalisch, Justine Chabanne, and Line Abou Zaki. 2023. SPARK Resilience in the workplace: Effectiveness of a brief online resilience intervention during the COVID-19 lockdown. PLoS ONE 18: e0271753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bratty, Alexandra J., and Nicole C. Dennis. 2024. The efficacy of employee strengths interventions on desirable workplace outcomes. Current Psychology 43: 16514–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calcagni, Cristián Coo, Marisa Salanova, Susana Llorens, Miguel Bellosta-Batalla, David Martínez-Rubio, and Rosa Martínez Borrás. 2021. Differential effects of mindfulness-based intervention programs at work on psychological wellbeing and work engagement. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 715146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, Kim, David Bright, and Arran Caza. 2004. Exploring the relationships between organizational virtuousness and performance. American Behavioral Scientist 47: 766–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carolan, Stephany, Peter R. Harris, and Kate Cavanagh. 2017. Improving employee well-being and effectiveness: Systematic review and meta-analysis of web-based psychological interventions delivered in the workplace. Journal of Medical Internet Research 19: e271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carr, Alan, Katie Cullen, Cora Keeney, Ciaran Canning, Olwyn Mooney, Ellen Chinseallaigh, and Annie O’Dowd. 2020. Effectiveness of positive psychology interventions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology 15: 749–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, Alan, Laura Finneran, Christine Boyd, Claire Shirey, Ciaran Canning, Owen Stafford, James Lyons, Katie Cullen, Cian Prendergast, Chris Cobett, and et al. 2023. The evidence-base for positive psychology interventions: A mega-analysis of meta-analyses. The Journal of Positive Psychology 19: 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, Alba, María Rubio-Aparicio, Guadalupe Molinari, Ángel Enrique, Julio Sánchez-Meca, and Rosa M. Baños. 2019. Effects of the best possible self intervention: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 14: e0222386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakhssi, Farid, Jannis Kraiss, Marion Sommers-Spijkerman, and Ernst T. Bohlmeijer. 2018. The effect of positive psychology interventions on well-being and distress in clinical samples with psychiatric or somatic disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 18: 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Taibo, Shuaikang Hao, Kaifang Ding, Xiaodong Feng, Gendao Li, and Xiao Liang. 2020. The Impact of Organizational Support on Employee Performance. Employee Relations 42: 1489–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbu, Alina, María Josefina Peláez Zuberbühler, and Marisa Salanova. 2021. Positive psychology micro-coaching intervention: Effects on psychological capital and goal-related self-efficacy. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 566293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeepSeek. 2024. DeepSeek LLM [Large Language Model]. Available online: https://github.com/deepseek-ai/DeepSeek-LLM (accessed on 30 March 2020).

- Dickens, Leah. 2017. Using gratitude to promote positive change: A series of meta-analyses investigating the effectiveness of gratitude interventions. Basic and Applied Social Psychology 39: 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, Scott, Joo Young Lee, and Stewart I. Donaldson. 2019. Evaluating positive psychology interventions at work: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Applied Positive Psychology 4: 113–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duval, Simon, and Richard Tweedie. 2000. A nonparametric “trim and fill” method of accounting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Journal of the American Statistical Association 95: 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, Matthias, George Davey Smith, Martin Schneider, and Christoph Minder. 1997. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 315: 629–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geerling, Bart, Jannis T. Kraiss, Saskia Kleders, Anja W. M. M. Stevens, Ralph W. Kupka, and Ernst T. Bohlmeijer. 2020. The effect of positive psychology interventions on well-being and psychopathology in patients with severe mental illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Positive Psychology 15: 572–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Yu-Fang, Louisa Lam, Virginia Plummer, Wendy Cross, and Jing-Ping Zhang. 2020. A WeChat-based “Three Good Things” positive psychotherapy for the improvement of job performance and self-efficacy in nurses with burnout symptoms: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Nursing Management 28: 480–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harty, Bo, John-Anders Gustafsson, Ann Björkdahl, and Anders Möller. 2016. Group intervention: A way to improve working teams’ positive psychological capital. Work 53: 387–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heaman, Maureen, Wendy A. Sword, Noori Akhtar-Danesh, Amanda Bradford, Suzanne Tough, Patricia A. Janssen, David C. Young, Dawn A. Kingston, and Aileen K. Hutton. 2014. Quality of prenatal care questionnaire: Instrument development and testing. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 14: 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedges, Larry V., and Ingram Olkin. 1985. Statistical Methods for Meta-Analysis. Orlando: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks, Tom, Marijke Schotanus-Dijkstra, Aabidien Hassankhan, Joop de Jong, and Ernst Bohmeijer. 2020. The efficacy of multi-component positive psychology interventions: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Happiness Studies 21: 357–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, Tom, Marijke Schotanus-Dijkstra, Aabidien Hassankhan, Tobi Graafsma, Ernst Bohlmeijer, and Joop de Jonhg. 2018. The efficacy of positive psychology interventions from non-Western countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Wellbeing 8: 71–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, Tom, Meg A. Warren, Marijke Schotanus-Dijkstra, Aabidien Hassankhan, Tobi Graafsma, Ernst Bohmeijer, and Joop de Jong. 2019. How WEIRD are positive psychology interventions? A bibliometric analysis of randomized controlled trials on the science of wellbeing. Journal of Positive Psychology 14: 489–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heskiau, Ravit, and Julie M. McCarthy. 2020. A work–family enrichment intervention: Transferring resources across life domains. Journal of Applied Psychology 106: 1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, Julian, and Simon G. Thompson. 2002. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Statistics in Medicine 21: 1539–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, Julian, Douglas G. Altman, Peter C. Gøtzsche, Peter Jüni, David Moher, Andrew D. Oxman, Jelena Savović, Kenneth F. Schulz, Laura Weeks, and Jonathan A. C. Sterne. 2011. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 343: d5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadad, Alejandro R., R. Andrew Moore, Dawn Carroll, Crispin Jenkinson, D. John M. Reynolds, David J. Gavaghan, and Henry J. McQuay. 1996. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: Is blinding necessary? Controlled Clinical Trials 17: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyes, Corey L. M. 2002. The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 43: 207–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, Risa, Makiko Mori, Miyuki Tajima, Hironori Somemura, Norio Sasaki, Megumi Yamamoto, Saki Nakamura, June Okanoya, Yukio Ito, Tempei Otsubo, and et al. 2015. Effect of a brief training program based on cognitive behavioral therapy in improving work performance: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Occupational Health 57: 169–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koydemir, Selda, Asli Bugay Sökmez, and Astrid Schütz. 2021. A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of randomized controlled positive psychological interventions on subjective and psychological well-being. Applied Research in Quality of Life 16: 1145–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulandaiammal, Rosy, and Meera Neelakantan. 2024. Effects of Mindfulness-Based Strengths Practice: A Conceptual Framework and Empirical Review of the Literature. International Journal of Mental Health 1: 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyubomirsky, Sonja, and Kristin Layous. 2013. How do simple positive activities increase well-being? Current Directions in Psychological Science 22: 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, David, Alessandro Liberati, Jennifer Tetzlaff, and Douglas G. Altman. 2009. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ 51: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, Scott B., and Richard P. DeShon. 2002. Combining Effect Size Estimates in Meta-Analysis with Repeated Measures and Independent-Groups Designs. Psychological Methods 7: 105–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumeier, Lena M., Libby Brook, Graeme Ditchburn, and Philipp Sckopke. 2017. Delivering your daily dose of well-being to the workplace: A randomized controlled trial of an online well-being programme for employees. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 26: 555–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, Karina, Morten B. Nielsen, Chidiebere Ogbonnaya, Marja Känsälä, Eveliina Saari, and Kerstin Isaksson. 2017. Workplace resources to improve both employee well-being and performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Work & Stress 31: 101–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oprea, Bogdan Teodor, Liubița Barzin, Delia Vîrgă, Dragoș Iliescu, and Andrei Rusu. 2019. Effectiveness of job crafting interventions: A meta-analysis and utility analysis. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 28: 723–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Shannon, Kiran Ali, Chanaka Kahathuduwa, Regina Baronia, and Yasin Ibrahim. 2022. Meta-analysis of positive psychology interventions on the treatment of depression. Cureus 14: e21933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, Acacia, and Robert Biswas-Diener. 2013. Positive interventions: Past, present, and future. In Mindfulness, Acceptance, and Positive Psychology: The Seven Foundations of Well-Being. Edited by Todd. B. Kashdan and Joseph Ciarrochi. Oakland: Context Press/New Harbinger Publications, pp. 140–65. [Google Scholar]

- Peláez Zuberbuhler, María Josefina, Cristián Coo, and Marisa Salanova. 2020a. Facilitating work engagement and performance through strengths-based micro-coaching: A controlled trial study. Journal of Happiness Studies 21: 1265–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peláez Zuberbuhler, María Josefina, Marisa Salanova, and Isabel M. Martínez. 2020b. Coaching-based leadership intervention program: A controlled trial study. Frontiers in Psychology 10: 3066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renshaw, Tyler, and Rachel M. Olinger Steeves. 2016. What Good Is Gratitude in Youth and Schools? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Correlates and Intervention Outcomes. Psychology in the Schools 53: 286–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, Richard D., Julian P. T. Higgins, and Jonathan J. Deeks. 2011. Interpretation of random effects meta-analyses. BMJ 342: d549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, Robert. 1979. The file drawer problem and tolerance for null results. Psychological Bulletin 86: 638–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, Carol, and Corey L. M. Keyes. 1995. The Structure of Psychological Well-Being Revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 69: 719–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Román-Niaves, Mabel, Cristian A. Vasquez, Cristian Coo, Karina Nielsen, Susana Llorens, and Marisa Salanova. 2024. Effectiveness of Compassion-Based Interventions at Work: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis Considering Process Evaluation and Training Transfer. Current Psychology 43: 22238–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutte, Nicola, and John M. Malouff. 2019. The impact of signature character strengths interventions: A meta-analysis. Journal of Happiness Studies 20: 1179–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, Mira, Franziska Feldmann, and Bernhard Schmitz. 2023. Art-of-living at work: Interventions to reduce stress and increase well-being. International Journal of Workplace Health Management 16: 89–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, Martin. 2018. PERMA and the building blocks of well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology 13: 333–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sexton, J. Bryan, and Kathryn C. Adair. 2024. Well-being outcomes of health care workers after a 5-hour continuing education intervention: The WELL-B randomized clinical trial. JAMA Network Open 7: e2434362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaghaghi, Fatemeh, Zahra Abedian, Negar Asgharipour, Habibollah Esmaily, and Mohammad Forouhar. 2020. Effect of positive psychology interventions on the quality of prenatal care offered by midwives: A field trial. Iranian Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research 25: 102–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, Kennon, and Laura A. King. 2001. Why positive psychology is necessary. American Psychologist 56: 216–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sin, Nancy, and Sonja Lyubomirsky. 2009. Enhancing well-being and alleviating depressive symptoms with positive psychology interventions: A practice-friendly meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology 65: 467–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares Marques, Nazaré, Miguel Pereira Lopes, and Sónia P. Gonçalves. 2021. Positive psychological capital as a predictor of satisfaction with the fly-in fly-out model. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 669524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, Louis, Cassondra Batz-Barbarich, Liu-Qin Yang, and Christopher W. Wiese. 2023. Well-being: The ultimate criterion for organizational sciences. Journal of Business and Psychology 38: 1141–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Jamovi Project. 2022. Jamovi (Version 2.4) [Computer Software]. Available online: https://www.jamovi.org (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Tonkin, Karen, Sanna Malinen, Katharina Näswall, and Joana C. Kuntz. 2018. Building employee resilience through wellbeing in organizations. Human Resource Development Quarterly 29: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyne, William P., David Fletcher, Nicola J. Paine, and Clare Stevinson. 2024. A prospective evaluation of the effects of outdoor adventure training programs on work-related outcomes. Journal of Experiential Education 47: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Erp, Kim J. P. M., Josette M. P. Gevers, Sonja Rispens, and Evangelia Demerouti. 2018. Empowering public service workers to face bystander conflict: Enhancing resources through a training intervention. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 91: 919–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vásquez-Pailaqueo, María, Hedy Acosta-Antognoni, and Marcelo Leiva-Bianchi. 2025. Character Strengths-Based Interventions and Their Efficacy Related to Work Engagement and Job Performance: A Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Applied Positive Psychology 10: 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, Anniina, Jessica de Bloom, Jo Annika Reins, Christine Syrek, Dirk Lehr, and Ulla Kinnunen. 2019. Promoting and prolonging the beneficial effects of a vacation with the help of a smartphone-based intervention. Gedrag & Organisatie 32: 287–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, Carmela Anna. 2016. Meta-Analyses of Positive Psychology Interventions on Well-Being and Depression: Reanalyses and Replication. Vancouver: University of British Columbia. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Paige, Margaret L. Kern, and Lea Waters. 2016. Exploring selective exposure and confirmation bias as processes underlying employee work happiness: An intervention study. Frontiers in Psychology 7: 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuliatun, Ismiyati, and Usmi Karyani. 2022. Improving the psychological well-being of nurses through Islamic positive psychology training. Psikohumaniora: Jurnal Penelitian Psikologi 7: 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boniwell et al. (2023) | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 5 |

| Bondre et al. (2025) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7 |

| Bratty and Dennis (2024)—Study 1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 6 |

| Bratty and Dennis (2024)—Study 2 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 6 |

| Calcagni et al. (2021) | Unclear | No | Unclear | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 3 |

| Corbu et al. (2021) | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | 4 |

| Guo et al. (2020) | Unclear | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Unclear | 2 |

| Harty et al. (2016) | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | 3 |

| Heskiau and McCarthy (2020) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 6 |

| Kimura et al. (2015) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | 6 |

| Soares Marques et al. (2021) | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | 2 |

| Neumeier et al. (2017) | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | 4 |

| Peláez Zuberbuhler et al. (2020b) | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Unclear | Yes | 4 |

| Peláez Zuberbuhler et al. (2020a) | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | 4 |

| Schwarz et al. (2023)—Study 1 | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 5 |

| Schwarz et al. (2023)—Study 2 | No | No | Unclear | No | Yes | No | Yes | 2 |

| Sexton and Adair (2024) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | 6 |

| Shaghaghi et al. (2020) | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 5 |

| Tonkin et al. (2018) | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | 4 |

| Tyne et al. (2024) | No | No | Yes | No | Unclear | No | Yes | 2 |

| Van Erp et al. (2018) | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 4 |

| Virtanen et al. (2019) | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Unclear | 3 |

| Williams et al. (2016) | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | 2 |

| Yuliatun and Karyani (2022) | Unclear | No | Yes | No | Unclear | No | Yes | 2 |

| Study | Country | % Female | Mean Age (SD) | Quality | Culture | Control Group | Follow-Up | Outcomes Included |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bondre et al. (2025) | India | 100.00 | 38.1 (6.9) | RCT | NW | AC | No | AHI; OSES |

| Boniwell et al. (2023) | France | 87.10 | 46.9 (10.80) | non-RCT | W | WL | No | PANAS; RS |

| Bratty and Dennis (2024)—Study 1 | EEUU | 50.70 | 41.20 (10.57) | RCT | W | AC | Yes | IRB; WPP |

| Bratty and Dennis (2024)—Study 2 | EEUU | 54.90 | 40.40 (9.66) | RCT | W | WL | No | IRB; UWES-9 |

| Calcagni et al. (2021)—MPSM * | Spain | 52.00 | 41.00 (6.92) | RCT | W | WL | Yes | HERO; SPWB |

| Calcagni et al. (2021)—MSCBI * | Spain | 41.00 | 45.50 (7.25) | RCT | W | WL | Yes | HERO; SPWB |

| Corbu et al. (2021) | Spain | 70.00 | 36.00 (7.50) | non-RCT | W | PC | No | PCQ |

| Guo et al. (2020) | Chinese Australia | 100.00 | 27.82 (5.42) | RCT | NW | PC | No | JC-TP-IP; GSS |

| Harty et al. (2016)—Gratitude * | Sweden | 81.08 | - | non-RCT | W | PC | Yes | JSS; LOT-R |

| Harty et al. (2016)—Optimism * | Sweden | 78.57 | - | non-RCT | W | PC | Yes | JSS; GSE |

| Heskiau and McCarthy (2020) | Canada | 82.00 | 43.16 (10.54) | RCT | W | PC | Yes | WFE |

| Kimura et al. (2015) | Japan | 14.30 | 46.40 (13.60) | non-RCT | W | PC | No | WP |

| Soares Marques et al. (2021) | Portugal | 28.00 | 37.00 | RCT | W | PC | Yes | JSS |

| Neumeier et al. (2017)—Gratitude * | Australia, Germany | 63.00 | 40.63 (13.53) | RCT | W | WL | No | SHS |

| Neumeier et al. (2017)—PERMA * | Australia, Germany | 72.00 | 41.67 (12.57) | RCT | W | WL | No | SHS |

| Peláez Zuberbuhler et al. (2020b) | Spain | 70.00 | 36.00 | non-RCT | W | PC | No | HERO; UWES-9 |

| Peláez Zuberbuhler et al. (2020a) | Spain | 15.00 | 45.00 (9.30) | non-RCT | W | PC | No | HERO; UWES-9 |

| Schwarz et al. (2023)—Both (Study 1) | Germany | 65.67 | 35.00 | RCT | W | AC | Yes | PANAS |

| Schwarz et al. (2023)—Stronguest (Study 1) | Germany | 65.67 | 35.00 | RCT | W | AC | Yes | AoL |

| Schwarz et al. (2023)—Weakness (Study 1) | Germany | 65.67 | 35.00 | RCT | W | AC | Yes | SWLS |

| Schwarz et al. (2023)—Work Training (Study 2) | Germany | 50.00 | 50.00 | non-RCT | W | WL | No | AoL; FS |

| Sexton and Adair (2024) | EEUU | 88.80 | 47.80 (18.50) | RCT | W | WL | No | EE-ER-R; WLI |

| Shaghaghi et al. (2020) | Iran | 100.00 | 28.80 (9.94) | RCT | NW | PC | No | QPCQ; OHQ; SPWB |

| Tonkin et al. (2018) | New Zealand | 85.00 | 42.00 (11.40) | RCT | W | PC | No | BFSS; CD-RISC/EmpRes |

| Tyne et al. (2024) | England | 63.00 | 38.70 (8.90) | non-RCT | W | NC | No | UWES-9; IWPQ |

| Van Erp et al. (2018) | Netherlands | 24.70 | 42.22 (7.35) | RCT | W | AC | No | OE7; WLI |

| Virtanen et al. (2019) | Finland | 85.00 | 44.75 (9.00) | non-RCT | W | PC | Yes | K10; PANAS |

| Williams et al. (2016) | Australia | 24.00 | - | non-RCT | W | PC | No | PCQ; OVS; UWES-9 |

| Yuliatun and Karyani (2022) | Indonesia | 53.00 | 40.00 | RCT | NW | PC | No | SPWB |

| Study | Intervention | Total Duration | PPI Sessions | Delivery Mode | Component | IGLO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bondre et al. (2025) | Character-strengths-based coaching intervention for work-stress reduction | 8 weeks | ≥8 sessions | In-Person | Multi | Individual |

| Boniwell et al. (2023) | SPARK resilience programme | 4 weeks and 12 h | ≥8 sessions | Remote | Multi | Individual |

| Bratty and Dennis (2024)—Study 1 | Three strengths-based approaches, top, bottom and mixed | 2 weeks and 3.5 h | <8 sessions | Remote | Single | Individual |

| Bratty and Dennis (2024)—Study 2 | Strengths Builder program developed by Niemiec and McGrath (2019) | 4 weeks | <8 sessions | Remote | Single | Individual |

| Calcagni et al. (2021)—MPSM | Mindfulness and Positive Stress Management (MPSM). | 3 weeks and 12 h | <8 sessions | In-Person | Multi | Individual |

| Calcagni et al. (2021)—MSCBI | Mindfulness and Self-Compassion Intervention (MSCBI) | 6 weeks and 18 h | <8 sessions | In-Person | Multi | Individual |

| Corbu et al. (2021) | Strengths-based micro-coaching program | 6 weeks and 5 h | <8 sessions | In-Person | Multi | Individual |

| Guo et al. (2020) | WeChat-based 3GT-positive psychotherapy. | 6 months | <8 sessions | Remote | Single | Individual |

| Harty et al. (2016)—Gratitude | Gratitude-based intervention | 10 weeks and 5 h | <8 sessions | In-Person | Multi | Group |

| Harty et al. (2016)—Optimism | Optimism-based intervention | 10 weeks and 5 h | <8 sessions | In-Person | Multi | Group |

| Heskiau and McCarthy (2020) | Work-to-family resource transfer training | 9 weeks and 0.66 h | ≥8 sessions | Remote | Multi | Leadership |

| Kimura et al. (2015) | CBT (cognitive behavioral therapy) | 3 weeks and 6 h | ≥8 sessions | Remote | Multi | Individual |

| Soares Marques et al. (2021) | HERO micro-intervention | 3 h | ≥8 sessions | In-Person | Multi | Individual |

| Neumeier et al. (2017)—Gratitude | Gratitude intervention | 2 weeks and 2 h | ≥8 sessions | Remote | Single | Individual |

| Neumeier et al. (2017)—PERMA | PERMA online wellbeing program | 2 weeks and 2 h | ≥8 sessions | Remote | Multi | Individual |

| Peláez Zuberbuhler et al. (2020b) | Strengths-based micro-coaching | 6 weeks and 5 h | <8 sessions | In-Person | Multi | Individual |

| Peláez Zuberbuhler et al. (2020a) | Coaching-based leadership intervention | 3 months | ≥8 sessions | In-Person | Multi | Leadership |

| Schwarz et al. (2023)—Both (Study 1) | Values and meaning of life art of living training (strengths and weakness) | 2 weeks | <8 sessions | Remote | Multi | Individual |

| Schwarz et al. (2023)—Strongest (Study 1) | Mindfulness and self-regulation art (strongest) | 2 weeks | <8 sessions | Remote | Multi | Individual |

| Schwarz et al. (2023)—Weakness (Study 1) | Emotional intelligence and positive relationships. Art of living training (weakness) | 2 weeks | <8 sessions | Remote | Multi | Individual |

| Schwarz et al. (2023)—Work Training (Study 2) | Comprehensive and adaptation to work context Art of living at work training | 2 weeks and 8 h | <8 sessions | In-Person | Multi | Individual |

| Sexton and Adair (2024) | Well-Being Essentials for Learning LifeBalance [WELL-B] intervention | 5 h | <8 sessions | Remote | Multi | Individual |

| Shaghaghi et al. (2020) | Training based on PERMA model | 8 weeks and 16 h | ≥8 sessions | In-Person | Multi | Individual |

| Tonkin et al. (2018) | 5 ways Wellbeing Game | 1 months | ≥8 sessions | Remote | Multi | Individual |

| Tyne et al. (2024) | Outdoor adventure | 2 days and 8 h | ≥8 sessions | In-Person | Multi | Organizational |

| Van Erp et al. (2018) | Bystander-conflict training intervention | 1.5 weeks and 68 h | ≥8 sessions | In-Person | Multi | Leadership |

| Virtanen et al. (2019) | DRAMMA Recovery daily training | 5 weeks | ≥8 sessions | Remote | Multi | Individual |

| Williams et al. (2016) | Psycap training | 3 days | <8 sessions | In-Person | Multi | Individual |

| Yuliatun and Karyani (2022) | Islamic-based positive psychology training of D. K. Hapsari et al. (2021) | 7 days | <8 sessions | In-Person | Multi | Individual |

| Outcome Measure | k | Hedge’s g | 95% CI | Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Between-group effects post-intervention | ||||

| Performance | 12 | 0.42 | [0.21, 0.62] | 3.98 ** |

| Subjective well-being | 16 | 0.50 | [0.18; 0.81] | 3.11 ** |

| Psychological well-being | 18 | 0.46 | [0.15; 0.78] | 2.89 ** |

| Within-group effects post-intervention | ||||

| Performance | 14 | 0.38 | [0.25; 0.50] | 6.03 ** |

| Subjective well-being | 18 | 0.39 | [0.19; 0.59] | 3.87 ** |

| Psychological well-being | 19 | 0.38 | [0.24, 0.51] | 5.39 ** |

| Outcome | Moderator | Group | k | g | 95% CI | Q (Within) | I2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjective Well-being | Culture | Western | 14 | 0.36 | [−0.97, 1.68] | 35.76 ** | 88% |

| Non-Western | 2 | −0.87 | [−1.87, 0.13] | - | - | ||

| Subjective Well-being | Format | In-person | 6 | 1.52 | [0.51, 2.53] | 45.4 ** | 93% |

| Remote | 10 | 0.90 | [−0.26, 2.06] | 20.3 ** | 54% |

| Outcome | Comparison Type | k | Hedges’ g | 95% CI | p | I2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjective well-being | Baseline vs. Follow-up (Experimental) | 9 | 0.42 | [−0.04, 0.88] | 0.073 | 91% |

| Post-test vs. Follow-up (Experimental) | 9 | 0.04 | [−0.08, 0.17] | 0.505 | 0% | |

| Experimental vs. Control (Follow-up) | 9 | 0.43 * | [0.05, 0.80] | 0.028 | 84% | |

| Psychological well-being | Baseline vs. Follow-up (Experimental) | 8 | 0.37 * | [0.08, 0.67] | 0.013 | 73% |

| Post-test vs. Follow-up (Experimental) | 8 | 0.02 | [−0.12, 0.16] | 0.791 | 0% | |

| Experimental vs. Control (Follow-up) | 5 | 0.51 * | [0.00, 1.02] | 0.050 | 77% | |

| Performance | Baseline vs. Follow-up (Experimental) | 5 | 0.50 ** | [0.16, 0.83] | 0.003 | 71% |

| Post-test vs. Follow-up (Experimental) | 5 | 0.02 | [−0.14, 0.18] | 0.807 | 7% | |

| Experimental vs. Control (Follow-up) | 3 | 0.43 ** | [0.13, 0.73] | 0.005 | 0% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martínez-Martínez, K.; Cruz-Ortiz, V.; Llorens, S.; Salanova, M.; Leiva-Bianchi, M. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Positive Psychology Interventions in Workplace Settings. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 481. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080481

Martínez-Martínez K, Cruz-Ortiz V, Llorens S, Salanova M, Leiva-Bianchi M. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Positive Psychology Interventions in Workplace Settings. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(8):481. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080481

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartínez-Martínez, Kevin, Valeria Cruz-Ortiz, Susana Llorens, Marisa Salanova, and Marcelo Leiva-Bianchi. 2025. "Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Positive Psychology Interventions in Workplace Settings" Social Sciences 14, no. 8: 481. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080481

APA StyleMartínez-Martínez, K., Cruz-Ortiz, V., Llorens, S., Salanova, M., & Leiva-Bianchi, M. (2025). Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Positive Psychology Interventions in Workplace Settings. Social Sciences, 14(8), 481. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080481