Hungarian Higher Education Beyond Hungary’s Borders as a Geostrategic Instrument

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Selection

2.2. Data Sources and Analytical Method

3. Demographic and Cultural Characteristics of Ethnic Hungarian Minorities Living in Hungary’s Neighbouring Countries

3.1. The Ethnic Hungarian Community Beyond Hungary’s Borders

3.2. Demographics of Ethnic Hungarian Minorities Living Beyond Hungary’s Borders

4. Results

4.1. Higher Education as a Geostrategic Instrument

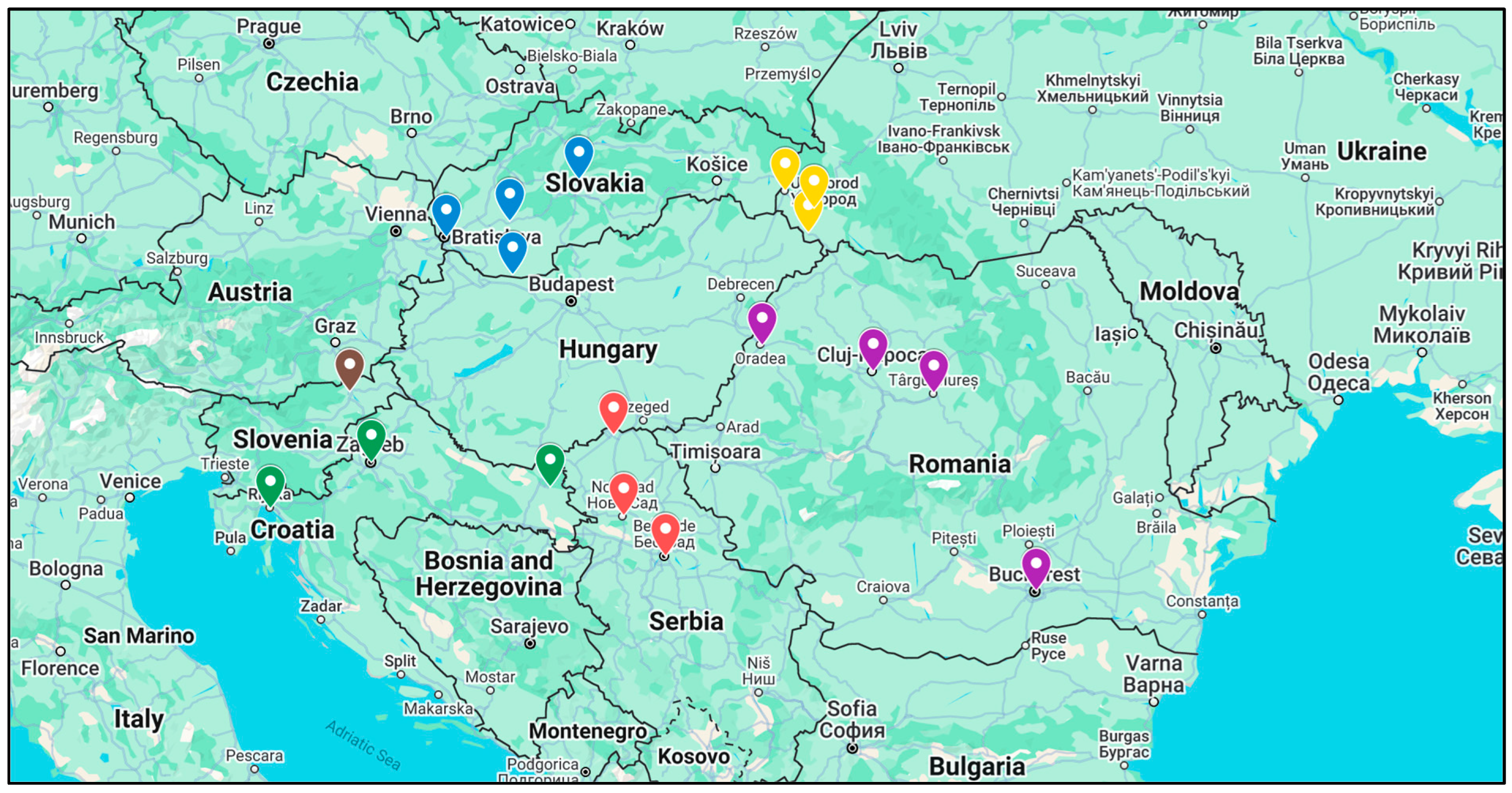

4.2. Hungarian Higher Education Beyond Hungary’s Borders

- The first group consists of higher education institutions that provide instruction entirely in Hungarian (e.g., Sapientia Hungarian University of Transylvania, Partium Christian University, J. Selye University, and the Ferenc Rákóczi II Transcarpathian Hungarian College of Higher Education).

- The second group includes institutions that offer Hungarian-language education alongside instruction in the national language (e.g., Babes–Bolyai University).

- The third group comprises universities that provide Hungarian-language education within one or more departments (e.g., Uzhhorod National University, Centre for Hungarian Studies) (Bodnár et al. 2019).

4.3. Hungarian Higher Education Beyond the Hungary’s Borders as a Geostrategic Instrument

4.4. Specific Forms of Intercultural Cohesion in Hungarian-Language Higher Education Institutions Beyond Hungary’s Borders

- National Minority—(E.g., Hungarian communities living beyond the border)

- Nationalizing State—The host country that employing nation-building strategies (e.g., Ukraine, Romania, Slovakia, etc.)

- External National Homeland—(E.g., Hungary) acting as a “protector” of the minority.

5. Discussion

5.1. The Strategic and Societal Role of Hungarian-Language Higher Education Beyond Hungary’s Borders

5.1.1. Preserving Identity, Building Community, and Advancing Geopolitical Instrument

5.1.2. The Dilemmas of Hungarian-Language Higher Education Beyond Hungary’s Borders

5.2. Limitations

5.3. Future Research Opportunities

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ablonczy, Balázs, and Nándor Bárdi. 2010. Határon túli magyarok: Mérleg, esély, jövő. In Határon Túli Magyarság a 21. Században. Edited by Botond Bitskey. Budapest: Köztársasági Elnök Hivatala, pp. 9–33. Available online: https://kisebbsegkutato.tk.hu/uploads/files/olvasoszoba/intezetikiadvanyok/Hataron_tuli_magyarsag_21_szazadban.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Anderson-Levitt, Kathryn M., ed. 2003. A World Culture of Schooling? In Local Meanings, Global Schooling. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- ARACIS. 2011. Law of National Education no. 1/2011 (as Amended until November 2022). Bucharest: Romanian Agency for Quality Assurance in Higher Education. Available online: https://www.aracis.ro/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Law-of-National-Education-no-1_2011_November-2022.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- B. K., Lok Bahadur, Yonghong Dai, Dipak Devkota, Ashok Poudel, and Zeyar Oo. 2025. Framing of China’s Soft Power in Nepal: A Case Study of Cultural and Educational Diplomacy in the Media. Media 6: 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bányai, Barna. 2020. Magyarország határon túli magyarokat érintő támogatáspolitikájának átalakulása 2010–2018 (I. rész). Regio 28: 171–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bárdi, Nándor. 2020. Közeli távolság: Magyarország és a határon túli magyarok viszonyairól. In Integrációs Mechanizmusok a Magyar Társadalomban. Edited by Imre Kovách. Budapest: Társadalomtudományi Kutatóközpont, pp. 311–70. Available online: http://real.mtak.hu/118646/1/integmech_teljes1.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Beelen, Jos, and Elspeth Jones. 2015. Redefining Internationalization at Home. In The European Higher Education Area. Edited by Adrian Curaj, Liviu Matei, Remus Pricopie, Jamil Salmi and Peter Scott. Cham: Springer, pp. 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blauberger, Michael, and Vera van Hüllen. 2020. Conditionality of EU Funds: An Instrument to Enforce EU Fundamental Values? Journal of European Integration 43: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodnár, Éva, Olga Csillik, Magdolna Daruka, Rita Horák, Melinda Nagy, Zsolt Orbán, Rita Pletl, Péter Szentesi, and Imre Tódor. 2019. Módszertani Mix—Kitekintés a Kárpát-Medencei Felsőoktatási Intézmények Módszertani Gyakorlatára. Budapest: Budapesti Corvinus Egyetem. Available online: https://unipub.lib.uni-corvinus.hu/4264/ (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Bottery, Mike. 2001. Education, Policy and Ethics. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Brubaker, Rogers. 1996. Nationalism Reframed: Nationhood and the National Question in the New Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Available online: https://nationalismstudies.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Nationalism-Reframed-Nationhood-and-the-National-Question-in-the-New-Europe-by-Rogers-Brubaker-z-lib.org_.pdf (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Castles, Stephen, Mark J. Miller, and Giuseppe Ammendola. 2005. The Age of Migration: International Population Movements in the Modern World. The Journal of the National Committee on American Foreign Policy 27: 537–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. 1995. Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/16800c10cf (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Csernicskó, István, János Péntek, and Gizella Szabómihály. 2010. A határon túli magyar nyelvváltozatok a többségi nyelvpolitikák rendszerében: Románia és Ukrajna példája. Regio—Kisebbség, Politika, Társadalom 21: 3–36. Available online: https://real-j.mtak.hu/14831/1/Regio_2010_3.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Csete, Örs, Attila Z. Papp, and János Setényi. 2010. Kárpát-medencei magyar oktatás az ezredfordulón. In Határon Túli Magyarság a 21. Században. Edited by Botond Bitskey. Budapest: Köztársasági Elnök Hivatala, pp. 44–54. Available online: https://kisebbsegkutato.tk.hu/uploads/files/olvasoszoba/intezetikiadvanyok/Hataron_tuli_magyarsag_21_szazadban.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Deardorff, Darla K. 2006. Identification and Assessment of Intercultural Competence as a Student Outcome of Internationalization. Journal of Studies in International Education 10: 241–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delors, Jacques. 1996. Learning: The Treasure Within; Report to UNESCO of the International Commission on Education for the Twenty-First Century. Paris: UNESCO Publishing. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000109590 (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training. 2013. Tertiary Attainment—Sustained Progress by European Union Member States. Available online: https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/data-insights/tertiary-attainment (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- European Commission. 2023. 2023 Rule of Law Report: Country Chapter on Hungary. Brussels: European Commission. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/publications/2023-rule-law-report-communication-and-country-chapters_en (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- European Union. 2012. Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union. Official Journal of the European Union. C 326/391. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:12012P/TXT (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Gallarotti, Giulio M. 2011. Soft Power: What It Is, Why It’s Important, and the Conditions for Its Effective Use. Journal of Political Power 4: 25–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Fang, and Jan Gube. 2020. Multicultural Education: How Are Ethnic Minorities Labelled and Educated in Post-Handover Hong Kong? Migration and Language Education 1: 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauttam, Priya, Bawa Singh, and Vijay Kumar Chattu. 2021. Higher Education as a Bridge between China and Nepal: Mapping Education as Soft Power in Chinese Foreign Policy. Societies 11: 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, Howard, Richard Y. Bourhis, and Donald M. Taylor. 1977. Towards a Theory of Language in Ethnic Group Relations. In Language, Ethnicity and Intergroup Relations. Edited by Howard Giles. London: Academic Press, pp. 307–48. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265966525 (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- Horváth, István, and Attila Z. Papp. 2018. Kisebbségi Magyar Felsőoktatás a Kárpát-Medencében: Rendszerleírások és Intézményi Adatok. Cluj-Napoca: Kisebbségkutató Intézet. [Google Scholar]

- Kádár, Béla. 2018. Az erdélyi magyar felsőoktatás és a munkaerőpiac kapcsolata. Opus et Educatio 5: 22–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kántor, Zoltán. 2007. Nationalizing Minorities and Homeland Politics. Razprave in Gradivo—Inštitut za Narodnostna Vprašanja 52: 156–84. Available online: https://www.dlib.si/details/URN:NBN:SI:DOC-LT5KWM6N?&language=eng (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Kincses, Áron. 2019. Magyar–magyar nemzetközi vándorlások a Kárpát-medencében, 2011–2017. Magyar Tudomány 180: 1676–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocsis, Károly, and Eszter Kocsis-Hodosi. 1998. Ethnic Geography of the Hungarian Minorities in the Carpathian Basin. Budapest: Geographical Research Institute, Hungarian Academy of Sciences. Available online: https://hungarian-geography.hu/konyvtar/kiadv/Ethnic_geography.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2025).

- Központi Statisztikai Hivatal. 2022. Népszámlálás 2022. Available online: https://nepszamlalas2022.ksh.hu/ (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Kugler, Tadeusz, and J. Patrick Rhamey. 2023. People and Places: The Contextual Side of Politics in Demography and Geography. Social Sciences 12: 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Jian. 2018. Conceptualizing Soft Power Conversion Model of Higher Education. In Conceptualizing Soft Power of Higher Education. Edited by Jian Li. Singapore: Springer, pp. 19–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magyarország Kormánya. 2015a. Fokozatváltás a Felsőoktatásban: A Teljesítményelvű Felsőoktatás Fejlesztésének Irányvonalai. Budapest: Magyarország Kormánya. Available online: https://2015-2019.kormany.hu/download/d/90/30000/fels%C5%91oktat%C3%A1si%20koncepci%C3%B3.pdf (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- Magyarország Kormánya. 2015b. Jelentés a Kormány Részére. A Külhoni Magyar Felsőoktatás Képzési Szerkezetének Átalakításáról, az Adott Régiókban Működő Felsőoktatási Intézmények és a Magyarországi Felsőoktatási intézmények Külhoni Székhelyen Kívüli Képzéseinek Összehangolásáról. Budapest: Kormány Határozat. [Google Scholar]

- Magyarország Kormánya. 2020. A Külhoni Magyar Felsőoktatás Helyzete és Fejlesztési Lehetőségei. Budapest: Kormány Határozat. [Google Scholar]

- Magyar Tudományos Akadémia. 2025. Kárpát-Medencei Magyar Nyelven is Oktató Felsőoktatási Intézmények. Available online: https://mta.hu/magyar-tudomanyossag-kulfoldon/karpat-medencei-magyar-nyelven-is-oktato-felsooktatasi-intezmenyek-105580 (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Mandel, Kinga Magdolna, and Tünde Morvai. 2022. Határon túli magyar oktatási támogatások 2010 és 2022 között. Educatio 31: 672–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscovitz, Hannah, and Emira Sabzalieva. 2023. Conceptualising the New Geopolitics of Higher Education. Globalisation, Societies and Education 21: 149–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemzetstratégiai Kutatóintézet. 2024. A Kárpát-Medencei Magyarság Népesség-Előreszámítása, 2011–2051. Available online: http://www.karpat-haza-statisztikak.hu (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- Palmisano, Flaviana, Federico Biagi, and Vito Peragine. 2022. Inequality of Opportunity in Tertiary Education: Evidence from Europe. Research in Higher Education 63: 514–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Su-Yan. 2013. Confucius Institute Project: China’s Cultural Diplomacy and Soft Power Projection. Asian Education and Development Studies 2: 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradise, James F. 2009. China and International Harmony: The Role of Confucius Institutes in Bolstering Beijing’s Soft Power. Asian Survey 49: 647–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pálfi, József. 2017. Huszonöt esztendő és ami mögötte van—A Partiumi Keresztény Egyetem első negyedévszázada. In Szülőföldön Magyarul. Iskolák és Diákok a Határon Túl. Edited by Gabriella Pusztai and Zsuzsanna Márkus. Debrecen: Debrecen University Press, pp. 98–111. Available online: https://mek.oszk.hu/18100/18141/18141.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Péti, Márton, Balázs Szabó, Mátyás Borbély, and Gergely Lovász. 2019. Kutatások, Vizsgálatok a Felsőoktatásra és Köznevelésre Hatást Gyakorló Tényezők, Tendenciák Megismerése Érdekében. Budapest: Nemzetstratégiai Kutatóintézet. [Google Scholar]

- Péti, Márton, Levente Pakot, Zoltán Megyesi, and Balázs Szabó. 2020. A Kárpát-medencei magyarság népesség-előreszámítása, 2011–2051. Demográfia 64: 269–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romsics, Ignác. 2011. Az Osztrák–Magyar Monarchia felbomlása és a trianoni békeszerződés. In Trianon 90 év Távolából. Edited by Ignác Romsics. Eger: Eszterházy Károly Főiskola Líceum Kiadó, pp. 15–40. Available online: https://publikacio.uni-eszterhazy.hu/5092/ (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Saarinen, Taina. 2020. Tensions on Finnish Constitutional Bilingualism in Neo-nationalist Times: Constructions of Swedish in Monolingual and Bilingual Contexts. In Language Perceptions and Practices in Multilingual Universities. Edited by Maria Kuteeva, Kathrin Kaufhold and Niina Hynninen. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 85–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedelmeier, Ulrich. 2013. Anchoring Democracy from Above? The European Union and Democratic Backsliding in Hungary and Romania. Journal of Common Market Studies 52: 105–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahjahan, Riyad A., and Clara Morgan. 2015. Global Competition, Coloniality, and the Geopolitics of Knowledge in Higher Education. British Journal of Sociology of Education 37: 92–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simsa, Tünde. 2022. A Kárpát-Medencében Élő Magyarok Demográfiája. Budapest: Országgyűlés Hivatala. Available online: https://www.parlament.hu/documents/10181/63638860/Elemzes_2022_Karpat_medence_magyarsaga.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Sobotka, Tomas, and Krystof Zeman. 2018. European Demographic Data Sheet 2018. Vienna: Vienna Institute of Demography. Available online: https://www.oeaw.ac.at/fileadmin/subsites/Institute/VID/PDF/Publications/Datasheet/DS2018/VID_DataSheet2018_Booklet.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Sütő, Zsuzsanna. 2014. Eljönni. Itt lenni. És visszamenni? A határon túli magyar hallgatók a magyarországi munkaerőpiacon. Educatio 23: 312–19. Available online: http://real.mtak.hu/id/eprint/102953 (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Takács, Zoltán. 2013. Felsőoktatási Határhelyzetek. Budapest: Magyar Tudományos Akadémia. Available online: https://mtt.org.rs/wp-content/uploads/Felsooktatasi-hatarhelyzetek-2013.pdf (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Tátrai, Patrik, József Molnár, Katalin Kovály, and Ágnes Erőss. 2020. SUMMA 2017: A Kárpátaljai Magyarok Demográfiai Felmérése. Budapest: Bethlen Gábor Alapkezelő Zrt. Available online: https://real.mtak.hu/114579/1/21_karpatalja_mozgasban_beliv.pdf (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Tóth, Norbert, and Balázs Vizi. 2024. A kisebbségek védelmének jogi keretei és jogalkalmazási tapasztalatai a magyarországgal szomszédos államokban. Kisebbségi Szemle 9: 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venice Commission. 2017. The Law on Education (Adopted by the Verkhova Rada on 5 September 2017). CDL-REF(2017)047. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. Available online: https://www.venice.coe.int/webforms/documents/default.aspx?pdffile=CDL-REF(2017)047-e (accessed on 19 July 2025).

- Venice Commission. 2023. Opinion on the Law on National Minorities (Communities) of Ukraine. CDL-AD(2023)021. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. Available online: https://www.venice.coe.int/webforms/documents/default.aspx?pdffile=CDL-AD(2023)021-e (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- World Bank Group. 2024. DataBank: Population Estimates and Projections. Available online: https://databank.worldbank.org (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Zuber, Christina Isabel. 2010. Understanding the Multinational Game: Toward a Theory of Asymmetrical Federalism. Comparative Political Studies 44: 546–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Area | 2011 | 2021/22 | 2031 * | 2051 * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vojvodina | 253,899 | 184,442 | 174,076 | 109,735 |

| Transylvania | ~1,200,000 | ~1,100,000 | 932,757 | 643,326 |

| Transcarpathia | ~130,000 ** | ~130,000 ** | 101,386 | 71,563 |

| Hungarian-inhabited southern Slovakia | ~508,000 | ~462,000 | 423,965 | 319,873 |

| Country Name | 2011 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|

| Hungary | 9,971,727 | 9,644,377 |

| Romania | 20,147,528 | 19,048,502 |

| Slovak Republic | 5,398,384 | 5,431,752 |

| Ukraine | 46,307,853 | 41,048,766 |

| Serbia | 7,236,519 | 6,664,449 |

| Country | Institutional Background | Covered Fields | Gaps |

|---|---|---|---|

| Romania | There are independent Hungarian-language institutions (several), and Hungarian-language faculties and centres | Nearly the full spectrum, Medical and Health Science—bilingual | Partially lacking in Agricultural Sciences, Public Administration, Law Enforcement, and Military Sciences |

| Serbia | No independent Hungarian-language institution, only Hungarian-language faculties and centres | Teacher Education, Arts and Humanities, and some programmes with Hungarian consultation | Engineering, Agricultural Sciences, Medical and Health Science, Economic Science, and Legal Science |

| Slovakia | There is an independent Hungarian-language institution, and Hungarian-language faculties and centres | Teacher Education, Theology, and Economic Science | Agricultural Sciences, Engineering, Medical and Health Science, Legal Science, and Arts |

| Ukraine | There is an independent Hungarian-language institution and Hungarian-language faculties and centres | Teacher Education, Arts and Humanities, and Natural Science | Agricultural Sciences, Medical and Health Science, Economic Science, Engineering, and Legal Science |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jávorffy-Lázok, A. Hungarian Higher Education Beyond Hungary’s Borders as a Geostrategic Instrument. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 459. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080459

Jávorffy-Lázok A. Hungarian Higher Education Beyond Hungary’s Borders as a Geostrategic Instrument. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(8):459. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080459

Chicago/Turabian StyleJávorffy-Lázok, Alexandra. 2025. "Hungarian Higher Education Beyond Hungary’s Borders as a Geostrategic Instrument" Social Sciences 14, no. 8: 459. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080459

APA StyleJávorffy-Lázok, A. (2025). Hungarian Higher Education Beyond Hungary’s Borders as a Geostrategic Instrument. Social Sciences, 14(8), 459. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14080459