Abstract

Henri Lefebvre’s “right to the city” has rarely been examined through an intersectional feminist lens, leaving unnoticed the uneven burdens that urban design and policy place on women. This article bridges that gap by combining constitutional analysis, survey data (n = 736), in-depth interviews, and participatory observation to assess how Quito’s public spaces affect women’s safety and mobility. Quantitative results show that 81% of respondents endured sexual or offensive remarks, 69.8% endured obscene gestures, and 38% endured severe harassment in the month before the survey; 43% of these incidents occurred only days or weeks beforehand, underscoring their routine nature. Qualitative narratives reveal behavioral adaptations—altered routes, self-policing dress codes, and distrust of authorities—and identify poorly lit corridors and weak institutional presence as spatial amplifiers of violence. Analysis of Quito’s “Safe City” program exposes a gulf between its ambitious rhetoric and its narrow, transport-centered implementation. We conclude that constitutional guarantees of participation, appropriation, and urban life will remain aspirational until urban planning mainstreams gender-sensitive design, secures intersectoral resources, and embeds women’s substantive participation throughout policy cycles. A feminist reimagining of Quito’s public realm is therefore indispensable to transform the right to the city from legal principle into lived reality.

1. Introduction

The conceptualization of the “right to the city”, introduced by Henri Lefebvre in the late 1960s, serves as a central framework in the discourse on urban justice and spatial democracy. Lefebvre proposed some fundamental premises for contemporary urban debate. His vision of the right to the city was not merely about access to urban resources; it emphasized the power to transform the city into a space that reflects the desires and needs of its inhabitants (Lefebvre 1968; Carrión 2020). This framework encompasses three principal lines of approach: the right to participation, which advocates for the active involvement of all individuals—especially marginalized groups—in shaping urban governance and policies; the right to appropriation, which asserts that people should be able to reshape urban spaces to fit their needs—resisting privatization; and, finally, the right to urban life, which envisions cities as environments where individuals can fully engage in social and cultural activities.

Lefebvre’s critique of modern cities highlights the alienation individuals endure and advocates for reimagining urban spaces as sites of collective belonging. Likewise, the principle of centrality and the concept of urban social space prioritize human interactions over purely economic imperatives. Yet these frameworks have remained largely gender-neutral, failing to account for how planning and policy decisions disproportionately impact women and other marginalized groups—an omission made more urgent by growing awareness of cities as arenas of entrenched social inequality and gendered violence (Mitchell 2003). The Ecuadorian Constitution enshrines the full enjoyment of the city and its public spaces (Art. 31) and guarantees a life free from violence (Art. 66). Nonetheless, the prevalence of sexual harassment in public areas effectively nullifies these constitutional rights, demonstrating the necessity of a rights-based and gender-sensitive approach to urban policy.

The political perspective offered by the constitution in defending equality and non-discrimination (Art. 11.2) and linking it to the right to a life free of violence is in dialogue with the framework proposed by Mark Purcell (2002), who frames the right to the city as a radical, anti-capitalist project. It can be affirmed that this view is also supported by David Harvey (2008) when emphasizing its utopian dimension, where we can mention the affirmative actions that the State proposes to promote real equality in favor of the rights holders who are in a situation of inequality, such as women. Finally, these approaches find their correlate with the right to the city in its revolutionary potential beyond the confines of legal liberalism Andy Merrifield (2012). While these theoretical contributions build upon Lefebvre’s original proposition, they represent distinct currents within the right to the city debate. Harvey, for instance, foregrounds class struggle and views the city as a terrain of anti-capitalist resistance; and Purcell emphasizes democratic self-management and collective governance, whereas Merrifield advocates for a revolutionary ethos that transcends legal liberalism. These nuances are particularly relevant when assessing the limitations of gender-neutral urban theories and the need to incorporate intersectional feminist perspectives into the conceptual core.

In the Metropolitan District of Quito—as in many cities worldwide—women’s right to the city is compromised by pervasive sexual harassment in public spaces, thus undermining both their safety and freedom of movement (Loukaitou-Sideris 2014). This article adopts a feminist lens to explore how urban design, governance structures, and constitutional norms converge to sustain or redress gender-based inequities in Quito.

To empirically ground these theoretical perspectives, this study focuses on a specific urban corridor in Quito that exemplifies both the promises and failures of modern urban planning. The empirical application was mainly located in Avenida Naciones Unidas—between Avenida 10 de Agosto and Avenida 6 de Diciembre—an axis often heralded as the city’s modernist emblem yet critiqued as a planning shortcoming. Through systematic field observations of pedestrian flows, transit stops, and street crossings, this study identifies spatial attributes that facilitate or hinder women’s urban engagement.

The necessity for such an investigation is underscored by the evolving discourse on gender and urbanism, which highlights the gendered nature of urban spaces and the critical role of urban policy in shaping women’s experiences of the city (Massey 1994; Palacios Jaramillo 2023). By employing qualitative methodologies, including surveys and interviews with women who have experienced sexual harassment in public spaces, alongside an analysis of urban policies, this research endeavors to elucidate the lived realities of women in Quito’s public spaces (2018–2019). There are no official sources or more recent studies on violence and harassment against women in public spaces, but there are data available on public transportation. In this context, it is known that, in 2024, 2 out of 10 women were victims of sexual harassment or abuse on public transportation (Municipio de Quito 2024).

It is fair to note that the theoretical lines on which this work is based prioritize the Global South thinking, contrasting ideas with theorists from the Global North. Bringing Latin American thinkers to the forefront first reflects this study’s commitment to situated and decolonial knowledge production from and for the South, not depreciating knowledge and experience produced in other geographies, but building academic synergy. In that line, it is important to note that frameworks developed in contexts marked by strong governance and distinct historical trajectories do not adequately engage with the structural and cultural forms of violence or with the everyday gender-based violence (tolerated and naturalized) and institutional fragmentation that characterize Quito. In that reason, this study necessarily articulates intersectionality, the right to the city, and urban safety through regional perspectives, thereby reinforcing its local relevance and critical contribution from the South, aligning with feminist scholarship that critiques the dominance of Global North epistemologies in urban theory and underscores the importance of situated, context-aware knowledge (Peake et al. 2021a).

The importance of utilizing the data obtained in 2018 and 2019 in this study lies these data’s ability to provide a robust empirical foundation that documents social and urban dynamics in public spaces, an aspect that is considered relevant for a located study. Although these data have not been updated, they remain fundamental for several reasons. Firstly, in the absence of recent statistics, they allow for the identification of patterns of violence against women in public spaces, demonstrating how they have persisted over time. Additionally, according to official data, such patterns are also evident in public transportation, suggesting that the phenomenon has not significantly changed, even in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. While these findings remain highly relevant in illustrating structural patterns of gender-based violence, their interpretation must be contextualized in a general framework of lack of research and data generation on gender-based violence in the city.

The absence of updated statistics, then, limits the ability to assess recent policy impacts or shifts in public behavior following the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, the results should be understood as a snapshot of persistent dynamics rather than as an exhaustive account of current conditions. It is also important to underline that municipal statistics are missing, which may reflect a lack of gender mainstreaming in important macro policies, e.g., on city design and transportation.

Despite not being recent, this study’s analytical approach remains both innovative and necessary to understand and address issues related to gender-based violence in urban contexts. At the same time, this study aims to contribute to new lines of thought that are built and reflected from the Global South, as mentioned in the lines above. It becomes evident that gender-based violence—violence inflicted solely based on being a woman—also encapsulates forms of sexist and misogynistic violence, as well as classist, ageist, racist, ideological, religious, identity-based, and political violence (Lagarde y de los Ríos 2024). In this context, this study critically assesses the effectiveness of existing urban policies and practices in ensuring women’s safety and rights, proposing a reimagined approach to urban planning that prioritizes inclusivity and gender equity which includes data generation and specific investigation. This perspective opens the possibility of constructing safer public spaces to foster peace and enable the free exercise of the right to the city.

It is with that intention that this study adopts a feminist perspective grounded not only in spatial justice and constitutional rights, but also in the ethics of peacebuilding. Drawing on the notion of feminism for peace, it explores how urban policy can dismantle both structural and symbolic violence, promoting public spaces where women can exercise their rights free from fear and exclusion. This research holds significant implications for policymakers, urban planners, and activists seeking to create more just and inclusive cities via the integration of gender perspective into urban planning. The goal is to prompt a reevaluation of current practices, fostering innovative strategies that prioritize the safety and rights of all city inhabitants, especially women. In doing so, this study contributes to the growing body of literature calling for a feminist re-configuration of urban spaces, advocating for a conceptualization of the right to the city that truly encompasses the diversity of urban residents’ experiences and aspirations (Butcher and Maclean 2018).

Through a detailed examination of the intersections among gender, urbanism, and constitutional rights, this investigation illuminates the specific challenges women face in Quito, while contributing to the broader discourse on the right to the city. As a normative concept, the right to the city still encompasses areas of uncertainty that impede its administrative and judicial effectiveness (Soriano Flores 2024). The concept of intersectionality, coined by Crenshaw (1989), describes how gender, ethnicity, class, and sexual orientation converge to produce compounded forms of discrimination. In Quito, these intersecting axes shape women’s experiences of insecurity in public spaces. While the sample primarily reflects the experiences of young, mestiza, educated women in Central–Northern Quito, their narratives offer valuable insights into broader structural patterns of gendered urban insecurity. Furthermore, intersectionality dialogues with the constitutional principles and can be integrated as an appropriated approach to building rights and achieving equality and justice. As proposed by Kuymulu (2013, p. 924, in Grigolo 2019), the notion of the right to the city, in the perspective of this article, “is increasingly becoming a conceptual vortex, pulling together discordant political projects that frame the urban problematic around democracy and human rights”.

This article presents the first intersectional assessment of the Quito Safe City program, combining survey data, ethnography, and legal analysis. The interdisciplinary perspective shows that despite public efforts such as improved lighting, structural gaps persist in nighttime transit and policing. Accordingly, it delivers a replicable matrix for auditing urban safety policies through the lens of the right to difference.

2. Materials and Methods

This study distinguishes itself through its interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary approach, particularly by incorporating ethnography as a key component of the fieldwork. The use of participant observation enriches and deepens the understanding of women’s lived experiences in Quito’s public spaces. This methodological choice enables a detailed exploration of the complex gender dynamics present in urban settings, providing a robust framework to analyze how public spaces can either reinforce or mitigate gender-based inequalities. These methodologies effectively capture the complex interplay between design, policy, and women’s lived realities in Quito by unpacking how urban design, public policies, and societal norms influence their sense of security, belonging, and ability to fully exercise their right to urban life.

By integrating ethnographic findings with feminist urban theory and constitutional analysis, this study offers a comprehensive perspective that not only enhances academic discourse but also delivers valuable recommendations for inclusive urban policymaking, suggesting, at the same time, the need to generate specific studies and statistics on the right to the city from a gendered perspective (gender-based violence in Quito).

The mixed-methods strategy employed herein includes extensive surveys; detailed, in-depth interviews; a robust policy analysis; and participatory observation. This multifaceted approach is designed to capture a holistic understanding of the right to the city from a gendered perspective, identifying barriers and facilitating a dialogue on transformative urban solutions (Rocchio et al. 2024b).

2.1. Data Collection

Surveys served as the initial phase of data collection, targeting a broad demographic of women residing in Quito. Its instrument was meticulously crafted to elicit responses on a range of experiences related to sexual harassment, perceived safety, and access to public spaces. Questions were designed to gauge both the frequency and intensity of these experiences, alongside the spatial contexts in which they occurred. Efforts were made to distribute the survey widely, utilizing online platforms and social networks to reach a diverse participant pool, thus ensuring a representative sample of the urban female population.

In-depth, semi-structured interviews (eleven) were carried out with eight female users (aged 18–40), two municipal officials, and one mobility specialist—purposively selected based on age, occupation, and frequency of movement. The interviews were conducted between July and October 2019, as part of the fieldwork specifically designed for this study (Baca Calderón 2019). Guided by a flexible interview protocol, these conversations delved into participants’ personal accounts of harassment, its emotional effects, and their interactions with urban infrastructure and governance. Interviewees were also invited to offer concrete suggestions for enhancing public-space design and policy, thereby enriching our understanding of how built environments and administrative frameworks influence women’s sense of safety and belonging.

Policy analysis was conducted concurrently, involving a thorough examination of current urban planning and gender-focused policies at both the municipal and national levels. This analysis scrutinized the legislative frameworks, strategic urban development plans, and specific initiatives aimed at enhancing gender safety and inclusivity in public spaces. The objective was to critically assess the alignment of these policies with the principles of the right to the city, evaluating their scope, implementation strategies, and effectiveness in safeguarding women’s rights in urban contexts.

Participatory observation complemented the methods, involving field visits to various public spaces within Quito. These observations provided insights into the physical layout, usage patterns (Porreca et al. 2019), and social dynamics of these spaces, offering a ground-level perspective on the factors that contribute to or detract from women’s feelings of safety and inclusion. The researcher engaged in passive observation, noting interactions, behaviors, and the overall atmosphere of the spaces, with a particular focus on gender dynamics and accessibility.

Although survey results identified the evening hours (6:00 p.m. to midnight) as the period when women felt most vulnerable, participatory observation was conducted primarily during daylight hours for ethical and safety reasons. This methodological choice, while limiting direct observation of nighttime dynamics, was mitigated by the richness of qualitative data obtained through interviews and surveys. These data provided detailed accounts of women’s experiences during those critical time frames, enabling this study to capture the emotional and spatial implications of nocturnal harassment without exposing the researcher to unnecessary risk.

2.2. Data Analysis

Between 3 and 10 January 2019, a Google Docs-based survey yielded 736 valid responses: by sex, 635 identified as female and 101 as male; and by gender identity, 626 as women and 9 as another gender (Baca Calderón 2019). Utilizing a snowball sampling strategy, the questionnaire targeted mestizo women aged 18–40, with higher education, residing in Quito’s central and northern districts, with participants encouraged to forward it to peers who had experienced street sexual harassment. The mean age was 27 years, with 40.6% aged 18–28, and 15.9% aged 29–40. Ethnically, 89% self-identified as mestiza, 7.9% as white, 1.1% as Afro-descendant, and 0.8% as indigenous.

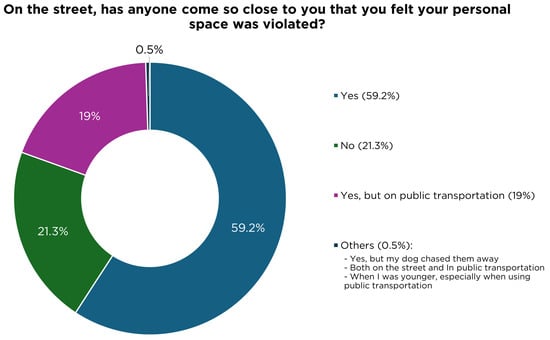

The survey included 21 questions with multiple-choice options, allowing respondents to add comments. Three questions were optional, enabling respondents to provide extended answers, which complicated data processing due to the unexpectedly high response rate of 500 women within the first 24 h. One of the optional questions asked, “If you have been a victim of street sexual harassment, could you share your experience?” Of the 338 responses, 10 highlighted elements of a crime, including the wearing of a skirt—the victim being blamed for clothing (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Data from survey “Characterization of Fear on the Street”. Source: Baca Calderón (2019).

Figure 2.

Data from survey “Fear of Public Space by Time”. Source: Baca Calderón (2019).

Quantitative data from the surveys underwent statistical analysis to identify significant patterns, correlations, and trends among the responses. This quantitative assessment aimed to delineate the prevalence of sexual harassment experiences among women in Quito and their impacts on mobility and perceived safety (Figure 3 and Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Data from survey “Mild Harassment”. Source: Baca Calderón (2019).

Figure 4.

Data from survey “Moderate Harassment”. Source: Baca Calderón (2019).

The qualitative data from the in-depth interviews were subjected to thematic analysis, which involved coding the transcripts to identify recurring themes, such as fear, altered mobility patterns, and distrust in institutional responses. These included feelings of fear and vulnerability, frequent changes in daily routes to avoid perceived threats, and disappointment in the reactions of police officers and public officials when harassment was reported. This process highlighted the personal and emotional dimensions of women’s experiences in public spaces, illuminating the complexities of their interactions with the urban environment.

2.3. Ethical Considerations

This study adhered to stringent ethical guidelines to protect the dignity, privacy, and well-being of all participants. Informed consent was a prerequisite for participation, with assurances of anonymity and confidentiality upheld throughout the research process. Ethical approval was secured from an institutional review board, ensuring that this study’s design and implementation met the highest standards of ethical research conduct. By employing this detailed and methodologically rigorous approach, this study seeks to illuminate the lived realities of women in Quito’s public spaces, contributing valuable insights to the discourse on gender, urbanism, and the right to the city. The findings are intended to inform policy discussions and urban-planning practices, advocating for inclusive, safe, and equitable urban environments that truly reflect the diverse needs and rights of all citizens.

3. Discussion

This investigation explores the nexus of the right to the city and gender equity in Quito’s Metropolitan District, focusing on how gender-based violence in public spaces shapes women’s urban experiences and undermines their rights. It examines how these experiences relate to constitutional guarantees—namely the rights to participation, appropriation, and urban life—through the lenses of women’s safety and sense of belonging. Building on Lefebvre, Michele Grigolo (2019) reconceptualizes the right to the city as a “right to difference”, explicitly embedding an intersectional perspective. In the discussion that follows, we consider how the collected data illuminate the challenges women face when navigating Quito’s urban spaces. A woman recounted, “I approached a police officer, and he said, ‘If he didn’t touch you, it’s not serious’” (Baca Calderón 2019). Our focus on Quito’s northern central area, as said, is due to its significance as a hub of urban life, where issues of public space utilization and safety are evident. Sexual harassment in public spaces is not an isolated issue but a widespread barrier to women’s full enjoyment of their right to the city (Loukaitou-Sideris 2014). This also affects the possibility to enjoy public space and the right to live in peace and freedom.

The methodological approach provided a thorough understanding of the interplay between urban design, policy, and women’s lived experiences, aligning with feminist epistemological frameworks that value situated knowledge (Haraway 1988). The findings from this study, conducted during 2018–2019, serve as the basis for this analysis (Baca Calderón 2019) and capture the voices of women navigating these spaces daily, highlighting the challenges of gender-based violence and the need for safer and more inclusive environments. These results contribute to the discourse on urban justice and provide practical insights for policymakers and urban planners. This study underscores the need for a feminist reimagining of urban spaces, advocating for inclusivity and safety that allow every individual to fully engage in urban life based on appropriation and active participation. It calls for cities that not only accommodate but celebrate diversity, fostering a sense of belonging and empowerment.

3.1. Urban Space and Gender-Based Violence: Conceptual Dimensions

This section explores the conceptual dimensions of the right to the city, examining how urban transformations, cultural norms, legal frameworks, and political dynamics shape women’s experiences in Quito’s public spaces.

From an interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary approach, this study analyzes gender-based violence in the urban environment and its impact on the exercise of the right to the city. Understanding the city not merely as a backdrop but as an active historical agent in human relations requires transcending disciplinary boundaries. This perspective captures the complexity of women’s experiences, shaped by the intersections of urban development, gender norms, and institutional structures. These experiences are marked by structural, symbolic, and direct violence, as reported by the participants themselves.

Among the 736 people who completed the digital survey distributed in January 2019, 91% of the women reported receiving unsolicited comments (“piropos”), and 84.5% had experienced lewd or objectifying stares in public spaces. In addition, 81% had been subjected to sexual or offensive remarks, and 38% had experienced at least one severe incident—such as unwanted touching, following, or indecent exposure—during the previous month. These figures confirm that public space, far from being a neutral setting, functions as a site of daily exposure, harassment, and threat for women.

Lefebvre’s (1968) notion of the “lived space” helps situate these experiences beyond the anecdotal. Violence is not only direct but embedded in the material configuration of the city: the absence of lighting, limited police presence, and poorly designed transit routes become mechanisms of exclusion that restrict access and full appropriation of the urban environment.

The survey results also reveal a persistent pattern of fear. A total of 384 women reported feeling afraid every day while moving through the city. This fear is heightened between 6:00 p.m. and midnight, the time range in which over 300 respondents expressed feeling particularly vulnerable. The constant perception of danger leads women to alter their routes, avoid certain places, and restrict their mobility and autonomy.

While the survey results clearly point to heightened fear during nighttime hours, this study’s observational component was conducted primarily during the day, due to safety and ethical constraints. This limitation is common in urban ethnographic research and highlights the need to triangulate methods. In this case, the discrepancy was addressed by relying on qualitative narratives from interviews and survey comments, which provided rich, first-hand accounts of women’s experiences after dark. These accounts offer critical insight into the spatial and emotional dimensions of nocturnal insecurity, reinforcing the need for inclusive and context-aware urban policy. When asked about measures that would help reduce harassment, the most frequently cited responses were improved lighting (64%), streets with continuous pedestrian presence (56.8%), visible police surveillance (47.3%), and increased commercial activity in public areas (53%). These responses highlight the direct connection between urban planning, infrastructure, and the experience of safety (Baca Calderón 2019).

While the enshrinement of the right to the city in Ecuador’s 2008 Constitution (Art. 31) marks an important legal milestone, its translation into effective public policy remains limited. The constitutionalizing of this right affirms urban space as a collective good and acknowledges participation, appropriation, and urban life as enforceable principles. However, without gender-sensitive institutional frameworks and cross-sectoral implementation, these rights risk remaining symbolic. In contexts marked by gendered violence and institutional fragmentation, such as Quito, constitutional guarantees alone cannot ensure substantive urban citizenship for women.

A feminist and intersectional approach reframes the right to the city not only as access to urban space, but as the ability to inhabit it freely, safely, and with dignity. It reveals how overlapping systems of oppression—gender, class, ethnicity, and age—shape women’s urban experiences and limit their autonomy. From this lens, the right to the city entails not only spatial inclusion, but the right to live without fear, to participate meaningfully in decision-making, and to transform urban environments that reproduce exclusion and violence. This perspective grounds the right to the city in lived realities and aligns it with constitutional mandates for equality and a life free from violence.

From García Canclini’s (2005) perspective, the city is also a site of knowledge production shaped by social disputes. Addressing gender-based violence in the urban environment requires methodological approaches that are critical, decolonial, and participatory—approaches that recognize emergent social actors and legitimate new forms of emancipation and engagement. Public space embodies a dual condition: exclusion and possibility. It is a contested site where power, access, and recognition are negotiated. As such, it becomes essential to design inclusive policies that guarantee safety and full participation, particularly for historically marginalized groups, including women (Rocchio and Domingo-Calabuig 2023).

The historical division between public and private space has shaped both urban planning and social practices, relegating women to the domestic sphere and limiting their participation in public life (Amorós 2019). Cities, designed historically by and for men, continue to reflect a patriarchal logic. This is evident in public policy and infrastructure, where the absence of a gender perspective constitutes a form of structural violence, reinforced by symbolic violence that renders women’s needs invisible. The omission of women’s voices restricts their right to participation and appropriation of urban space.

A feminist reimagining of the right to the city must therefore confront these exclusions and design urban environments that are genuinely inclusive and safe for all (Kern 2021). This requires rethinking legal and planning frameworks through feminist and critical lenses that center women’s rights and experiences.

In this context, our analysis examines how public policies may either reproduce or challenge gender-based violence in urban space. This evaluation of legal frameworks and planning instruments goes beyond identifying gaps; it seeks to determine how these tools can be restructured to support women’s full participation and right to the city. It is possible to understand how gender, law, and space intersect. This approach shows that traditional legal and urban frameworks often fail to consider women’s specific needs—particularly concerning mobility and safety in public space (Brickell and Cuomo 2019).

This discussion is directly linked to Ecuador’s constitutional framework. The 2008 Constitution explicitly recognizes both the right to a life free of violence and the right to the city, aligning with international standards such as CEDAW and the Belém do Pará Convention (Comité de la CEDAW 2015). These provisions oblige the State to prevent violence, protect women from gender-based harm, and ensure their full participation in society, particularly in public spaces. However, the implementation of these constitutional guarantees remains limited. Many public policies still lack a gender-sensitive approach, which hinders progress toward safer and more inclusive urban environments. As has also been observed in the Mexican context, the right to the city has not yet been fully integrated into policies targeting vulnerable groups, including migrant women (Ortega Ramírez 2024).

This disparity between the normative strength of Ecuador’s constitutional framework and its limited enforcement reflects a broader challenge: legal recognition alone is insufficient when unaccompanied by institutional capacity, political will, and accountability mechanisms. Gender-sensitive rights require not only constitutional inscription but concrete operationalization through policy, budgeting, investigation, and enforcement. Without such alignment, rights remain aspirational rather than transformative. The Ecuadorian Constitution introduces a transformative paradigm that centers on equality, inclusion, and sustainability, articulated through the principle of Buen Vivir. This framework promotes a feminist urban agenda that guarantees women’s right to navigate the city without fear or discrimination. In line with this, the Quito Safe City initiative, led by UN Women (2019), aimed to address sexual harassment in public transport and urban settings. While the program introduced campaigns like “Bájale al acoso”, mobile reporting tools, and staff training, its impact has been limited primarily to the transport system. Broader urban interventions remain underdeveloped, revealing a gap between policy intentions and structural change. This study thus underscores the need for urban policy grounded in constitutional principles and international human rights standards, committed to transforming public space into a domain that is equitable, safe, and fully accessible for women. The evidence presented illustrates the convergence of urban form, gender inequality, and legal guarantees, and calls for a feminist reconfiguration of public space to ensure the full realization of women’s right to the city (Rainero 2009).

3.2. Women’s Experiences in Quito’s Public Spaces

Building upon the interdisciplinary framework and the conceptual foundation of the right to the city, this section examines the lived experiences of women in Quito’s public spaces. The analysis is grounded in quantitative and qualitative data gathered through surveys, in-depth interviews, and participatory observations. Together, these sources reveal the scope and everyday manifestations of gender-based violence in the city—violence that restricts women’s mobility, undermines their safety, and limits their full participation in urban life.

The survey, completed by 736 respondents—635 of whom identified as female by sex and 626 by gender—confirms that street harassment is a widespread and recurrent experience. Among the participants, 81% reported having received sexual or offensive comments, 69.8% had experienced obscene gestures or sounds, and 84.5% had been subjected to intimidating or objectifying stares. Additionally, 38% of respondents reported having experienced severe forms of harassment—including unwanted touching, being followed, or public exposure—within the month prior to the survey. Notably, 43% of these incidents occurred in the immediate weeks preceding the survey, indicating the high frequency of such events. These figures illustrate the normalization of street harassment in Quito’s public spaces, signaling a structural failure to ensure women’s right to move freely and safely in the city

These quantitative findings are supported by testimonies that express the emotional and everyday impact of harassment. One participant recalled, “I approached a police officer, and he said: ‘If he didn’t touch you, it’s not serious’”. The interviews revealed (Baca Calderón 2019) a persistent climate of insecurity and vigilance experienced by women in Quito’s public spaces. Many participants described having to modify their behavior, clothing choices, or daily routes in response to past incidents of harassment.

One interviewee noted the following: “There’s this constant sense of alertness… you walk fast, avoid eye contact, and always think about what to do if something happens”. Another added, “It’s not just fear. It’s exhaustion. Every day you calculate which route feels less dangerous”. These testimonies reflect how gender-based violence reshapes daily behaviors and produces a state of permanent self-surveillance. In several accounts, women also linked this fear to institutional indifference: “I reported it, and the officer said: ‘This is not worth filing, nothing happened’”. These narratives reinforce the dissonance between women’s lived realities and institutional responses, highlighting the need for structural reforms that center women’s experiences in urban safety agendas.

Encounters with institutional actors, such as the police, often resulted in dismissive or minimizing responses that deepened their sense of vulnerability. The emotional toll of navigating the city under constant threat was a recurring theme, with several women reporting heightened anxiety, fear, and a sense of isolation. These narratives underscore how everyday experiences of harassment shape women’s relationship with the urban environment and constrain their access to the city.

This study also draws on participatory observations conducted in central–northern public areas of Quito. These revealed that poorly lit spaces, isolated paths, and the absence of visible surveillance increase vulnerability to harassment. In contrast, well-lit areas with continuous pedestrian flow and police presence were perceived as safer and more welcoming. Urban design and infrastructure thus emerge as key factors in either exacerbating or mitigating gender-based violence. Places such as the Naciones Unidas Boulevard—despite its modern infrastructure—were identified as unsafe due to the lack of adequate furniture, limited nighttime activity, and minimal institutional presence. This underscores that safety depends not only on physical infrastructure, but also on the social and symbolic configuration of space.

In this context, it is crucial to recognize that urban inequalities are closely tied to social reproduction (Peake et al. 2021b). In Quito, the lack of public policies that incorporate this dimension contributes to the persistent marginalization of women and their exclusion from safe and accessible public spaces. This research also highlights the value of feminist approaches to the study of urban violence, particularly those grounded in methodologies such as Participatory Action Research (PAR). This perspective promotes the active involvement of women in knowledge production, makes their experiences in public space visible, and strengthens the understanding of the structural conditions that sustain violence (Brickell and Cuomo 2020).

Based on the analysis, three key lines of action are proposed for public policy:

- Redesign urban space from a gender-sensitive perspective that prioritizes safety and equity;

- Implement institutional protocols that effectively and sensitively address street harassment;

- Ensure women’s active participation in the planning, implementation, and monitoring of urban policy.

The articulation of empirical data, personal testimonies, and theoretical frameworks supports the conclusion that women’s right to the city can only be fully realized when material, symbolic, and institutional barriers are addressed simultaneously. The gap between constitutional guarantees and the lived realities of women in urban environments highlights the urgent need for integrated policies that ensure free and safe access to public space.

3.3. Toward a Feminist Reimagining of Urban Spaces

The culmination of this research pivots toward the reimagination of urban spaces that fully embrace and embody the right to the city for women, aligned with the principles of gender equity and safety (Ferrajoli 2002).

The strategies and recommendations of this study, drawn from a transdisciplinary approach, are rooted in empirical data and theoretical insights. These foundations highlight the transformative potential that public policies and urban-planning practices hold when properly informed and applied.

In revisiting the Quito Safe City policy (UN Women 2019), this analysis critically evaluates its effectiveness in translating constitutional guarantees into urban practice. This review highlights obstacles in implementing the policy on the ground and its consequences for women’s everyday experiences in the city.

The Quito Safe City initiative seeks to confront the specific risks women face in public spaces, but its practical impact falls short of its conceptual framework. While it includes campaigns, mobile reporting tools, and staff training, implementation has focused mainly on the transportation system. This narrow reach stems less from a lack of vision and more from weak intersectoral coordination, limited budget allocation, and low political prioritization. As a consequence, other vulnerable urban areas—such as streets, parks, and pedestrian corridors—remain largely unaddressed in terms of gender-based violence prevention. Although the reporting mechanism improves the ability to document incidents, its lack of interoperability with emergency services and the absence of protocols tailored to Indigenous women constrain its overall effectiveness. By contrast, comparable programs in Bogotá and Mexico City incorporate georeferencing modules and immediate community-based security responses. To bridge this divide, Quito must strengthen its technological infrastructure and deepen collaboration with local stakeholders. To achieve the above, there must be a deliberate change in urban-planning practices. It necessarily includes the adoption of gender-sensitive designs and interventions that directly address the unique needs and experiences of women in the urban context.

Addressing the contributors to gender-based violence in public spaces is crucial, particularly elements that are found in the design of infrastructure and services like inadequate lighting and surveillance that escalate women’s vulnerability. Furthermore, the active participation of civil society and women’s movements is essential in advancing the conversation about safe public spaces and catalyzing meaningful change in urban policy and design. This means contributing to the deconstruction of symbolic violence, and not only structural violence, due to the lack of a gender-sensitive design.

However, particular solutions such as increased street lighting do not address the systemic issues or structural violence that perpetuate women’s insecurity in urban spaces. A feminist approach requires structural changes in policies and urban design that dismantle these patriarchal foundations, promoting a truly inclusive urban planning that responds to women’s experiences and needs (Kern 2021; Antonucci et al. 2024).

The active engagement and advocacy of civil society, particularly women’s movements, are instrumental in ensuring accountability from policymakers. Their involvement is key to prioritizing gender equity in the understanding, planning, and development of urban spaces. This advocacy lays the foundation for transforming urban environments into places where safety and equality are interwoven into the very fabric of the city, paving the way for the creation of empowering and safe public spaces. Creating spaces that go beyond merely being violence-free, a feminist reimagining of public environments focuses on empowerment and active participation. It is about designing spaces that enable women to feel secure and confident in their right to the city.

The construction of identity and the expression of diversity are central to this process, enabling women to navigate public spaces without fear or restriction. This translates into a life free of violence and the possibility of living in peace.

4. Forward-Looking Perspectives: Envisioning an Inclusive Urban Future

As we chart the course for a more inclusive urban future, it becomes imperative to envision public spaces not just as they are, but as they ought to be. In Quito, the potential for a city that truly embodies the right to the city for all, particularly for women, hinges on our ability to turn constitutional assurances into lived realities. Our study, while rooted in the present, offers a forward-looking perspective on how Quito can become a paradigm of gender-inclusive urbanism.

The gap between the constitutional ideals outlined by the Republic of Ecuador and the experiences of women in Quito’s public spaces must be narrowed through actionable, future-oriented policies (Constitución de la República del Ecuador 2008). With that aim, the “Safe City” initiative (ONU Mujeres 2019) represents a positive stride toward this goal; however, its effectiveness will be measured by how well it adapts and responds to the evolving challenges women face in urban settings. Moving forward, policies must be dynamic, grounded in empirical evidence and the lived experiences of women, and agile enough to adapt to new challenges and insights.

The urban landscape of the future must be designed with a gendered lens, incorporating safety, accessibility, and inclusivity at the core of its architecture Rocchio and Moya (2017). It must go beyond perfunctory changes and aim to transform the very fabric of urban life. This means creating public spaces that not only deter potential threats but also promote women’s autonomy, empowerment, and participation. Urban planners, therefore, need to integrate gender-sensitive design principles that make public spaces truly accessible, safe, and welcoming to women. Civil society, particularly women’s movements—as in the scope of other rights—has a significant role to play in this urban transformation. Their advocacy and activism must continue to shape urban policies and ensure that gender equity remains a central tenet of urban development. Additionally, collaboration between policymakers, urban designers, sociologists, and the community at large is crucial in constructing urban environments that reflect the diverse needs of their inhabitants. This collaboration becomes even more critical when data and lived experiences reveal the insecurity and vulnerability that women face in their everyday lives.

As we look toward the future, the conversation on urban spaces must evolve to encapsulate a discourse that is inclusive, participatory, and reflective of the pluralistic nature of the city. This brings us back to the conceptual framework on which this article is based, which encompasses the right to participation, the right to appropriation, and the right to urban life. This involves dismantling structural, symbolic, and direct violence, as well as entrenched social norms, and fostering a cultural shift that elevates respect and dignity for all, within every street, park, and public space (Porreca and Rocchio 2016). The future of urban spaces lies in the promise of equal rights, security, and opportunities, where the right to the city is not an abstract concept but a tangible reality for every citizen, irrespective of gender.

Embracing the concept of a “feminist right to the city” is essential, since it focuses on ensuring that women have access to public spaces without fear of violence or exclusion. As argued by Peake et al. (2021b), public services and spaces should be recognized as feminist rights, enabling women to navigate the city safely. This approach reinforces the need for a feminist reimagining of urban policies in Quito, suggesting that safety and inclusion are not merely add-ons, but fundamental rights that must be enshrined in urban policy.

Enriching Peake’s view, we emphasize that the right to the city can and should be built from “feminism for peace”. This concept invites us to understand feminism “as a theory and praxis of life that unites the conviction for the equality of women and men with the knowledge to transform power relations and build recognition and real exercise of women’s human rights, deconstructing and repudiating all forms of violence from a pacifist empowerment” (Sánchez 2021, p. 93). This notion, in the case of study, implies the deconstruction of violence and the commitment to building safe spaces where there will be no room for either structural or symbolic violence. In this way, with the interdisciplinary view of this article, rooted from a gender perspective, it is possible to see the necessary dynamic balances that make up human life and the public policies (Rocchio et al. 2024a). These can make possible or not the transformations of both the legal-institutional construction (with the necessary participation of women) and the design of policies (that allow women to live the right to the city by hearing their experiences and needs). This would be finally reflected in the conception and physical construction of spaces that may be more or less safe for all inhabitants.

5. Conclusions

Our exploration of the right to the city from a feminist perspective in Quito transcends academic inquiry; it serves as a clarion call for societal transformation. This study advocates for reimagining power relations embedded in the conception and design of urban spaces to uphold and advance women’s human rights. The empirical results analyzed allow us to say that the right to participation, the right to appropriation, and the right to urban life cannot be achieved without incorporating specific measures to promote equality and prevent violence; in our perception, this necessarily requires a gender approach and respect for the principle of equality and non-discrimination proposed by the constitution itself.

Given that the Constitution of Ecuador provides a progressive legal framework recognizing women’s rights, our research reveals that the practical realization of these rights within urban environments remains insufficient. Achieving genuine gender equality in urban spaces requires more than legal provisions; it necessitates cultural and social evolution, including the deconstruction of all forms of violence and necessarily including budget forecast for its execution. The “Safe City” initiative in Quito, while commendable, needs to be both strengthened and expanded through the active participation of the women it seeks to protect. Policies must reflect women’s lived experiences, ensuring they are not only relevant but also effective in bringing tangible improvements to their daily lives. Such inclusive policy-making, grounded in real-world realities and supported by robust enforcement mechanisms, is essential for Quito to transform into a truly safe and equitable city for all.

This research underscores the importance of embedding gender sensitivity into the core of urban planning and governance. Urban design must serve as a tool for ensuring women’s safety, enhancing their mobility, and fostering their autonomy. The right to the city must move beyond theoretical constructs to become a lived reality for all citizens (Park 1999), addressing the diverse experiences of women and other marginalized groups. In quantitative terms, this study provides a comprehensive overview of the state of gender equity in Quito’s urban landscape during 2018–2019, offering a critical benchmark for future research. It highlights that, despite constitutional recognition, the gap between policy and practice remains wide. The findings serve as a reminder that urban spaces must evolve into arenas where women’s rights are asserted, respected, and celebrated. This work contributes to the discourse on gender-sensitive urban planning by calling for a shift that prioritizes women’s perspectives in reshaping public spaces. It proposes an urban future where policies informed by women’s experiences actively reconfigure public spaces to be inclusive and safe for all genders, embodying constitutional rights to the city in practice, not merely in principle.

Building peace from and for women through the right to the city is a central tenet of this study, challenging and deconstructing traditional, male-centered paradigms of urban development. These theoretical and practical perspectives contribute to a feminist, context-sensitive framework for public policy. Minimum policy parameters include the collection and use of intersectional data; enforceable accountability mechanisms; and gender-and-care-oriented urban design, such as well-lit environments, inclusive street furniture, and designated safe routes.

6. Policy Implications and Recommendations

The investigation into the right to the city from a feminist perspective necessitates a critical examination of public policies and their effectiveness in safeguarding women’s rights and safety in Quito’s urban spaces. Despite constitutional guarantees for a life free from violence and the right to the city (Constitución de la República del Ecuador 2008), the implementation of these rights in urban policies reveals significant gaps.

6.1. Evaluating Quito’s “Safe City” Initiative

Quito’s “Safe City” initiative, intended to enhance women’s safety in public spaces (ONU Mujeres 2019), provides a case study for analyzing the gap between policy intentions and outcomes. Although this policy represents a step toward addressing gender-based violence in urban environments, its effectiveness is limited by challenges in implementation and enforcement, and the lack of a gender-sensitive approach in urban planning (Baca Calderón 2019). This echoes findings from other studies that emphasize the necessity of integrating gender considerations into urban design and policy-making to create safe and inclusive public spaces. Thus, it underscores the necessity of further research to analyze the relationship between existing legislation, the institutions responsible for implementing these policies through social programs, and the outcomes achieved in the prevention and response to violence against women (Ovalle Magallanes and Rangel Bernal 2024).

6.2. The Need for Comprehensive Public Policies

The findings from this study underline the importance of developing and implementing comprehensive public policies that go beyond legal sanctions against perpetrators of gender-based violence. Such policies should address the structural causes of gender inequality in urban spaces and aim to redesign public areas to ensure women’s safety and comfort. This study suggests that an interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary approach is crucial in crafting policies that genuinely protect and empower women in urban settings.

6.3. Recommendations for Policy and Urban Planning

Minimum policy parameters include the collection and use of intersectional data; enforceable accountability mechanisms; and gender- and care-oriented urban design, such as well-lit environments, inclusive street furniture (Rocchio 2014), and designated safe routes.

Based on the insights gained from this investigation, several recommendations emerge for policymakers and urban planners:

- (a)

- Incorporate gender sensitivity into urban design: Urban planning should prioritize the creation of well-lit, populated, and surveilled public spaces that deter potential harassers and provide a sense of safety for all women (Baca Calderón 2019).

- (b)

- Engage women in policy-making processes: Women’s participation in the formulation, implementation, and evaluation of urban policies ensures that their voices and experiences inform the creation of safer urban environments (Muxi Martínez 2011).

- (c)

- Implement educational campaigns: Raising awareness about gender-based violence and promoting respectful behaviors in public spaces can contribute to cultural change and reduce incidents of harassment.

- (d)

- Strengthen legal frameworks and enforcement: While laws exist to prevent and punish acts of sexual harassment, enforcement is often lacking. Strengthening legal frameworks and ensuring strict enforcement are necessary to deter perpetrators.

The intersection of urban planning, gender studies, and constitutional rights offers a unique lens through which to examine and address the challenges women face in public spaces. By adopting a feminist perspective in the development and implementation of public policies, cities like Quito can move closer to realizing the right to the city for all their inhabitants, ensuring that public spaces are safe, inclusive, and empowering for women. The recommendations outlined in this research provide a roadmap for re-envisioning Quito’s public spaces in a way that transcends traditional urban-planning paradigms. By embedding gender equity into the core of urban design and policy, we can aspire to a cityscape that is truly reflective of its diverse inhabitants, ensuring that the right to the city is a lived reality for women.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C.B.C.; Methodology, E.S.B.; Validation, M.C.B.C.; Formal analysis, E.S.B. and D.R.; Investigation, M.C.B.C., E.S.B. and D.R.; Data curation, G.Q.; Writing—original draft, M.C.B.C.; Writing—review & editing, M.C.B.C., G.Q., E.S.B. and D.R.; Supervision, M.C.B.C. and D.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The empirical material used in the study is entirely based on an undergraduate thesis previously completed by the first author, María Carolina Baca. Therefore, no new application to an Ethics Committee or Institutional Review Board was necessary. At the time the original thesis was prepared, the institution did not require a formal ethics approval process for undergraduate research projects of this nature. The study adhered strictly to established ethical standards to protect the dignity, privacy, and well-being of all participants. All procedures followed internationally recognized ethical guidelines, including those outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants were thoroughly informed of the study’s purpose, methodology, and their right to withdraw at any stage.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study prior to their involvement, with anonymity and confidentiality rigorously maintained throughout the research process.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in http://hdl.handle.net/10644/7070 (accessed on 25 January 2025).

Acknowledgments

Los autores han revisado y editado los resultados obtenidos y asumen la plena responsabilidad del contenido de esta publicación».

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Amorós, Celia. 2019. Espacio público, espacio privado y definiciones ideológicas de lo ‘masculino’ y lo ‘femenino’. San Pedro: IIDH. [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci, Maria Cristina, Ilaria Di Tullio, and Teresa Pullano. 2024. A feminist perspective on urban politics and social space in the neo-liberal city. Theoretical outlooks and social practices in the Italian context. H-hermes: Journal of Communication 2023: 185–206. [Google Scholar]

- Baca Calderón, Maria C. 2019. Re-pensar el centro norte del D.M. Quito: Una lectura feminista del derecho a la ciudad en clave constitucional. Master’s dissertation, Universidad Andina Simón Bolívar, Quito, Ecuador. [Google Scholar]

- Brickell, Katherine, and Dana Cuomo. 2019. Feminist geolegality. Progress in Human Geography 43: 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brickell, Katherine, and Dana Cuomo. 2020. Geographies of Violence: Feminist Geopolitical Approaches. In Routledge International Handbook of Gender and Feminist Geographies. Edited by Anindita Datta, Peter Hopkins, Lynda Johnston, Elizabeth Olson and Joseli Maria Silva. Routledge: Londres, pp. 297–307. [Google Scholar]

- Butcher, Melissa, and Kate Maclean. 2018. Gendering the city: The lived experience of transforming cities, urban cultures and spaces of belonging. Gender, Place & Culture 25: 686–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canclini, Néstor García. 2005. La Antropología Urbana en México. México: Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana. [Google Scholar]

- Carrión, Fernando. 2020. El Derecho a la Ciudad: Una Aproximación. FLACSO Andes. Available online: https://www.flacsoandes.edu.ec/sites/default/files/%25f/agora/files/FA-AGORA-2020-Carrion.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Comité de la CEDAW. 2015. Recomendación General No. 12. Violencia contra la Mujer. 1989. Recomendación General No. 33. Formas de discriminación contra la mujer. Available online: https://www.refworld.org/es/leg/coment/cedaw/1989/es/131609 (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Constitución de la República del Ecuador. 2008, Quito, Ecuador: Government of Ecuador, October 20.

- Crenshaw, Kimberlé W. 1989. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum 1989: 139–67. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrajoli, Luigi. 2002. Derechos y Garantías. La ley del Más Débil. Madrid: Editorial Trotta. [Google Scholar]

- Grigolo, Michele. 2019. Understanding the right to the city as the right to difference. Monografías CIDOB 76: 23–32. Available online: https://www.michele-grigolo.com/1/11/resources/publication_3238_1.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Haraway, Donna. 1988. Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective. Feminist Studies 14: 575–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, David. 2008. The right to the city. New Left Review 53: 23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kern, Leslie. 2021. Feminist City: Claiming Space in a Man-Made World. London: Verso Books. [Google Scholar]

- Kuymulu, Mehmet Bariş. 2013. The vortex of rights: “Right to the city” at a crossroads. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 37: 923–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagarde y de los Ríos, Maria. 2024. For the life and freedom of women: End to femicide. ATLÁNTICAS—Revista Internacional de Estudios Feministas 9: 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, Henri. 1968. Le Droit à la Ville. Paris: Anthropos. [Google Scholar]

- Loukaitou-Sideris, Anastasia. 2014. Fear and safety in transit environments from the women’s perspective. Security Journal 27: 242–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, Doreen. 1994. Space, Place, and Gender (NED-New Edition). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.cttttw2z (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Merrifield, Andy. 2012. The Politics of the Encounter: Urban Theory and Protest Under Planetary Urbanization. Athens: University of Georgia Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, Don. 2003. The Right to the City: Social Justice and the Fight for Public Space. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Municipio de Quito. 2024. Estudio de Violencia Sexual en el Sistema de Transporte Metropolitano y Línea Base del Estudio de Violencia Sexual en el Metro de Quito. Quito: Municipio de Quito. [Google Scholar]

- Muxi Martínez, Zaida. 2011. Reflexiones en torno a las mujeres y el Derecho a la Ciudad desde una realidad con espejismos. In El Derecho a la Ciudad. Barcelona: Institut de Drets Humans de Catalunya. [Google Scholar]

- ONU Mujeres. 2019. “Crear espacios seguros”. ONU Mujeres. Accedido 20 de junio de 2019. Available online: https://www.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/Headquarters/Attachments/Sections/Library/Publications/2020/Safe-Cities-and-Safe-Public-Spaces-International-compendium-of-practices-02-es.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Ortega Ramírez, Adriana Sletza. 2024. Migraciones, derecho a la ciudad y utopía: El caso de Ciudad de México. Estudios Fronterizos 25: e146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovalle Magallanes, Myriam, and Laura Rangel Bernal. 2024. Empoderamiento para una vida libre de violencia: Análisis de un programa social dirigido a mujeres en situación vulnerable. Journal of Feminist, Gender and Women Studies 16: 82–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios Jaramillo, Patricia del Carmen. 2023. La experiencia diferencial de género en el espacio urbano. Maskana 14: 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Robert Ezra. 1999. La Ciudad y Otros Ensayo de Ecología Urbana. Barcelona: Ediciones del Serbal. [Google Scholar]

- Peake, Linda, E. Koleth, G. S. Tanyildiz, and A. Narayanareddy. 2021a. Placing feminist political geography: The situated and global politics of knowledge production. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 45: 120–38. [Google Scholar]

- Peake, Linda, Elsa Koleth, Gokboru Sarp Tanyildiz, and Rajyashree N. Reddy, eds. 2021b. A Feminist Urban Theory for Our Time: Rethinking Social Reproduction and the Urban. Hoboken: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Porreca, Riccardo, and Daniele Rocchio. 2016. Distancias socio-espaciales en la reconstrucción pos-desastre. Eídos, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porreca, Riccardo, Vasiliki Geropanta, Ricardo Moya Barberá, and Daniele Rocchio. 2019. Remote Sensing Drones for Advanced Urban Regeneration Strategies. The Case of San José de Chamanga in Ecuador. In Intelligent Computing and Optimization. ICO 2019. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing. Edited by Pandian Vasant, Ivan Zelinka and Gerhard-Wilhelm Weber. Cham: Springer, vol. 1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, Mark. 2002. Excavating Lefebvre: The Right to the City and Its Urban Politics of the Inhabitant. GeoJournal 58: 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainero, Liliana. 2009. Ciudad, espacio público e inseguridad. Aportes para el debate desde una perspectiva feminista. In Mujeres en la Ciudad: De Violencias y Derechos. Santiago: Ediciones SUR, p. 168. [Google Scholar]

- Rocchio, Daniele. 2014. Sustentabilidad Ambiental: Estrategias y Proyectos Arquitectónicos. Quito: Corporación para el Desarrollo de la Educación Universitaria. [Google Scholar]

- Rocchio, Daniele, and Débora Domingo-Calabuig. 2023. The pre-design phase in the post-catastrophe intervention process. The case of Chamanga, Ecuador. Bitácora Urbano Territorial 33: 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocchio, Daniele, and Ricardo J. E. Moya. 2017. Del objeto al proceso: El paisaje de la reconstrucción post-catástrofe. Eídos 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocchio, Daniele, Débora Domingo-Calabuig, Majid Khorami, Sebastian Narvaez-Purtschert, and Adrián Patricio Beltrán Montalvo. 2024a. Dinámicas temporales y espaciales en la reconstrucción post-desastre: Una reflexión sobre las interacciones multiescala. Anales De Investigación En Arquitectura, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocchio, Daniele, Fernando Bustamante, and María Carolina Baca Calderón. 2024b. Convivir en la ciudad: Una reflexión sobre la percepción de inseguridad en el espacio público. Eídos 17: 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, Eufemia. 2021. Mujeres, Participación Política y Pazentre la Preconstituyente de Mujeres y la Constitución de Montecristi (Ecuador). Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/tesis?codigo=289403 (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Soriano Flores, José Jesús. 2024. La juridificación del derecho humano a la ciudad como punto de partida en el diseño de políticas públicas para el siglo XXI. Revista Mexicana de Análisis Político y Administración Pública, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Women. 2019. Quito, Ecuador: Safe Cities and Safe Public Spaces. United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women. Available online: https://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/ending-violence-against-women/creating-safe-public-spaces (accessed on 25 January 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).