Authoritarianism in the 21st Century: A Proposal for Measuring Authoritarian Attitudes in Neoliberalism

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Integrate the four dimensions of neoliberal authoritarianism into a single scale, elaborating items updated to the present time.

- Determine the validity and internal reliability of the instrument, as well as the adjustment of the suggested four-dimensional model (composed of the dimensions Authoritarian Aggression, Authoritarian Submission, Conventionalism, and Neoliberalism) through the application of the instrument to a sample obtained from the general population residing in Spain.

- Propose adjustments to the instrument based on the results obtained.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Instrument

- Authoritarian Aggression: the tendency to cause harm (physical and/or psychological) to those sanctioned by the authorities perceived as legitimate and who belong to the exogroup.

- Authoritarian Submission: subordination to the rules dictated by the authorities perceived as legitimate.

- Conventionalism: acceptance of and commitment to conventional social values and norms accepted by society and endorsed by the established authorities.

- Neoliberalism: tendency to accept economic policies of market deregulation and to adopt meritocratic attitudes.

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis

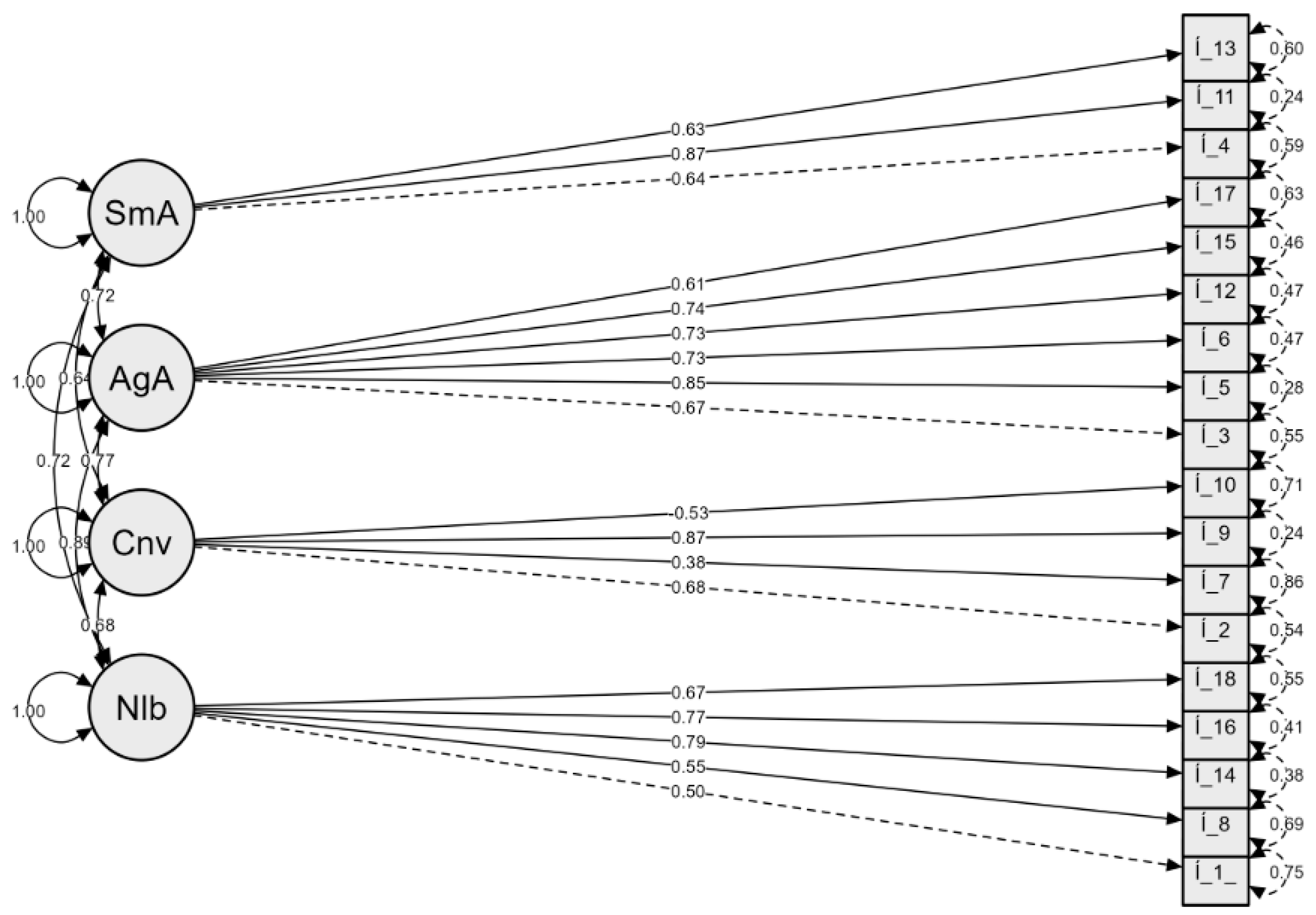

3.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

- The weights corresponding to each dimension are over 0.40 in every item except item 7, which belongs to the Conventionalism dimension. All are significant (p < 0.001) (see Table 7).

- The mean R-Squared for each dimension is more than 40%. Specifically, it is 52% in Authoritarian Aggression, 44% in Neoliberalism, 52% in Authoritarian Submission, and 41% in Conventionalism (see Table 7).

- All dimensions are positively and significantly related (p < 0.001) (see Table 8).

3.3. Correlation Analysis

3.3.1. Correlation Between Factors

3.3.2. Item-Factor Correlation

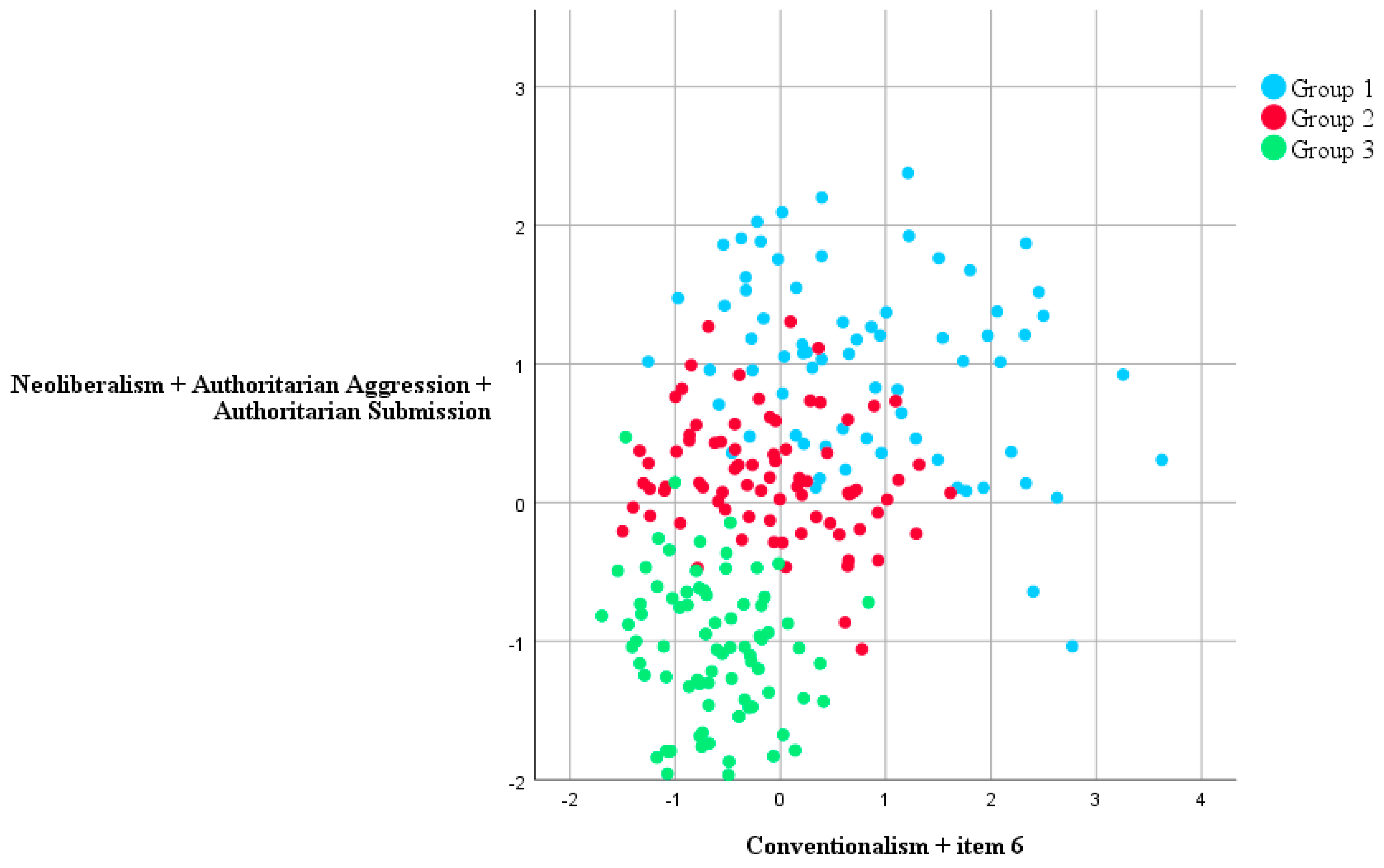

3.4. Hierarchical Cluster Analysis

3.5. Reliability Analysis

4. Discussion

- (1)

- A statement of work autonomy through a reduction in bureaucracy. The central principle of this objective is to ensure that the connection between one’s desires and actions does not result in adverse consequences or emotional distress. This phenomenon aligns with a period of technological advancements that facilitate a reduction in work hours and the organization of personal lives around non-capitalist objectives, such as achieving a true work–life balance. This approach is likely to yield substantial benefits in terms of mental health.

- (2)

- An affirmation of personal autonomy that goes beyond the private and markedly individualistic idea of autonomy in neoliberalism, where the figure of the “other” disappears. It is necessary to build relational autonomy, as suggested by Palop (2019). This approach facilitates independence or uniqueness through the cultivation of healthy relationships with others, thus recognizing diversity and interdependence in existence. It demonstrates a proclivity to comprehend the notion of the “self” as defined by the “other,” thereby facilitating the reemergence of solidarity within the collective.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adorno, Theodor W., Else Frenkel-Brunswik, Daniel J. Levinson, and Nevitt Sanford. 2006. La Personalidad Autoritaria (Prefacio, Introducción y Conclusiones) [The Authoritarian Personality (Preface, Introduction and Conclusions)]. Empiria Revista de Metodología de Ciencias Sociales 12: 155–200. First published 1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altemeyer, Bob. 1981. Right-Wing Authoritarianism. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altemeyer, Bob. 1988. Enemies of Freedom: Understanding Right-Wing Authoritarianism. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Altemeyer, Bob. 1996. The Authoritarian Specter. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association. 2010. Enmiendas de 2010 a los “Principios éticos de los psicólogos y código de conducta” de 2002 [2010 Amendments to the 2002 “Ethical Principles for Psychologists and Code of Conduct”]. American Psychologist 65: 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amigot, Patricia, and Laureano Martínez. 2022. Procesos de (auto) subjetivación en la trama neoliberal. Una aproximación a las técnicas de sí y sus condiciones de posibilidad. Encrucijadas: Revista Crítica de Ciencias Sociales 22: 10. [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo, Flavio, John T. Jost, Tobias Rothmund, and Joanna Sterling. 2019. Neoliberal Ideology and the Justification of Inequality in Capitalist Societies: Why Social and Economic Dimensions of Ideology Are Intertwined: Neoliberal Ideology and Justification. The Journal of Social Issues 75: 49–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barni, Daniela, Nicoletta Cavazza, Silvia Russo, Alessio Vieno, and Michele Roccato. 2020. Intergroup contact and prejudice toward immigrants: A multinational, multilevel test of the moderating role of individual conservative values and cultural embeddedness. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 75: 106–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bay-Cheng, Laina Y., Caroline C. Fitz, Natalie M. Alizaga, and Alyssa N. Zucker. 2015. Tracking Homo Oeconomicus: Development of the Neoliberal Beliefs Inventory. Journal of Social and Political Psychology 3: 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beierlein, Constanze, Frank Asbrock, Mathias Kauff, and Peter Schmidt. 2014. Die Kurzskala Autoritarismus (KSA-3): Ein ökonomisches Messinstrument zur Erfassung dreier Subdimensionen autoritärer Einstellungen. GESIS-Working Papers, 2014/35. Mannheim: GESIS—Leibniz-Institut für Sozialwissenschaften. Available online: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-426711 (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Bizumic, Boris, and John Duckitt. 2018. Investigating Right Wing Authoritarianism With a Very Short Authoritarianism Scale. Journal of Social and Political Psychology 6: 129–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Wendy. 2021. En las Ruinas del Neoliberalismo: El Ascenso de las Políticas Antidemocráticas en Occidente. Mi-Wuk Village: Traficantes de Sueños. [Google Scholar]

- Bruff, Ian. 2014. The rise of authoritarian neoliberalism. Rethinking Marxism 26: 113–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruff, Ian, and Cemal B. Tansel, eds. 2020. Authoritarian Neoliberalism: Philosophies, Practices, Contestations. Oxfordshire: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cabezas, Marta, and Cristina Vega, eds. 2022. La Reacción Patriarcal: Neoliberalismo Autoritario, Politización Religiosa y Nuevas Derechas. Barcelona: Bellaterra Edicions. [Google Scholar]

- Cuéllar, David P. 2017. Subjetividad y psicología en el capitalismo neoliberal. Revista Psicología Política 17: 589–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dardot, Pierre, and Christian Laval. 2019. Anatomía del nuevo neoliberalismo. Viento Sur 164: 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- del Campo, Felix. 2023. New culture wars: Tradwives, bodybuilders and the neoliberalism of the far-right. Critical Sociology 49: 689–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckitt, John. 2015. Authoritarian personality. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences 2: 255–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckitt, John, and Boris Bizumic. 2013. Multidimensionality of right-wing authoritarian attitudes: Authoritarianism-conservatism-traditionalism. Political Psychology 34: 841–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckitt, John, and Chris G. Sibley. 2010. Personality, ideology, prejudice, and politics: A dual-process motivational model. Journal of Personality 78: 1861–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duckitt, John, and Kirstin Fisher. 2003. The Impact of Social Threat on Worldview and Ideological Attitudes. Political Psychology 24: 199–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunwoody, Philip T., and Friedrich Funke. 2016. The Aggression-Submission-Conventionalism Scale: Testing a new three factor measure of authoritarianism. Journal of Social and Political Psychology 4: 571–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duriez, Bart, and Alain Van Hiel. 2002. The march of modern fascism. A comparison of social dominance orientation and authoritarianism. Personality and Individual Differences 32: 1199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, Stanley. 2003. Enforcing Social Conformity: A Theory of Authoritarianism. Political Psychology 24: 41–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Savater, Amador. 2024. Capitalismo Libidinal. Antropología Neoliberal, Políticas del Deseo, Derechización del Malestar. Washington: Ned Ediciones. [Google Scholar]

- Forti, Steven. 2021. Extrema Derecha 2.0: Qué es y Cómo Combatirla [Extreme Right 2.0: What It Is and How to Combat It]. Madrid: Siglo XXI España Editores. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foucault, Michel. 2010. Nacimiento de La Biopolitica. Curso En El College de France (1978–1979). [Birth of biopolitics: Course at the Collège de France (1978–1979)]. Madrid: Ediciones Akal. First published 1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, Thomas. 2015. ¿Qué pasa con Kansas?: Cómo los Ultraconservadores Conquistaron el Corazón de Estados Unidos [What’s the Matter with Kansas? How Conservatives Won the Heart of America]. Madrid: Antonio Machado Libros. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, Nancy. 2017. From Progressive Neoliberalism to Trump—and Beyond. American Affairs 1: 46–64. [Google Scholar]

- Funke, Friedrich. 2005. The Dimensionality of Right-wing Authoritarianism: Lessons from the Dilemma between Theory and Measurement. Political Psychology 26: 195–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, Ernesto. 2022. Three varieties of Authoritarian Neoliberalism: Rule by the experts, the people, the leader. Competition & Change 26: 554–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandesha, Samir. 2017. De la personalidad autoritaria a la personalidad neoliberal. [From the authoritarian personality to the neoliberal personality]. Estudios Politicos 41: 127–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, Ayline, Oliver Decker, Bjarne Schmalbach, Manfred Beutel, Jörg M. Fegert, Elmar Brähler, and Markus Zenger. 2020. Detecting authoritarianism efficiently: Psychometric properties of the screening instrument authoritarianism–ultra short (A-US) in a German representative sample. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 533863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henrich, Joseph. 2022. Las Personas Más Raras del Mundo: Cómo Occidente Llegó a Ser Psicológicamente Peculiar y Particularmente Próspero [The Weirdest People in the World: How the West Became Psychologically Peculiar and Particularly Prosperous]. Madrid: Capitán Swing. [Google Scholar]

- Ipar, Ezequiel. 2018. Neoliberalismo y Neo-autoritarismo. Política y Sociedad 55: 825–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jay, Sarah, Anatolia Batruch, Jolanda Jetten, Craig McGarty, and Orla T. Muldoon. 2019. Economic inequality and the rise of far-right populism: A social psychological analysis. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology 29: 418–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonason, Peter K., and Gregory Webster. 2010. The Dirty Dozen: A concise measure of the Dark Triad. Psychological Assessment 22: 420–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost, John T., Mahzarin R. Banaji, and Brian A. Nosek. 2004. A decade of system justification theory: Accumulated evidence of conscious and unconscious bolstering of the status quo. Political Psychology 25: 881–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, Karl G., and Dag Sörbom. 1993. LISREL 8: Structural Equation Modeling with the SIMPLIS Command Language. Chapel Hill: Scientific Software International. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layton, Matthew L., Amy E. Smith, Mason W. Moseley, and Mollie J. Cohen. 2021. Demographic polarization and the rise of the far right: Brazil’s 2018 presidential election. Research & Politics 8: 2053168021990204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lázaro, Carlos M. D., Claudia Castañeiras, Rubén D. Ledesma, Susana Verdinelli, and Avonelle Rand. 2016. Right-wing authoritarianism, social dominance orientation, empathy, and materialistic value orientation as predictors of Intergroup prejudice in Argentina. Salud & Sociedad 5: 282–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, Melvin J. 1980. The Belief in a Just World. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 9–30. [Google Scholar]

- Lloret-Segura, Susana, Adoración Ferreres-Traver, Ana Hernández-Baeza, and Inés Tomás-Marco. 2014. El análisis factorial exploratorio de los ítems: Una guía práctica, revisada y actualizada. Annals of Psychology 30: 1151–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loehlin, John C. 1992. Latent Variable Models: An Introduction to Factor, Path, and Structural Analysis, 2nd ed. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merchand, Marco A. 2020. Desigualdad e Ideología neoliberal antidemocrática. Revista Kavilando 12: 175–90. [Google Scholar]

- Muñiz, José. 2018. Introducción a la Psicometría: Teoría Clásica y TRI. Madrid: Pirámide. [Google Scholar]

- Muñiz, José, and Eduardo Fonseca-Pedrero. 2019. Diez pasos para la construcción de un test. Psicothema 31: 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñiz, José, Ángel Fidalgo, Eduardo García-Cueto, Rafael Martínez, and Rafael Moreno. 2005. Análisis de los ítems. Madrid: La Muralla. [Google Scholar]

- Noval, Noelia, and María D. L. V. Moral. 2019. Participación política y autoritarismo: Interrelación y diferencias en función de variables sociodemográficas. Revista de Psicología 28: 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovejero, Anastasio. 2015. Psicología social crítica y emancipadora: Fertilidad de la obra de José Ramón Torregrosa [Critical and emancipatory social psychology: Fertility of the work of José Ramón Torregrosa]. Quaderns de Psicología 17: 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Palop, María E. R. 2019. Revolución Feminista y Políticas de lo Común Frente a la Extrema Derecha. Buenos Aires: Clacso. [Google Scholar]

- Passini, Stefano. 2008. Exploring the multidimensional facets of authoritarianism: Authoritarian aggression and social dominance orientation. Swiss Journal of Psychology 67: 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peresman, Adam, Royce Carroll, and Hanna Bäck. 2021. Authoritarianism and Immigration Attitudes in the UK. Political Studies 71: 616–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratto, Felicia, Jim Sidanius, Lisa M. Stallworth, and Bertram F. Malle. 1994. Social dominance orientation: A personality variable predicting social and political attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 67: 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiroz, Mauricio I. L. 2011. Criterios de coherencia y pertinencia para la evaluación inicial de planes y programas de pregrado: Una propuesta teórico-metodológica. REXE: Revista de Estudios y Experiencias en Educación 10: 49–72. [Google Scholar]

- Reguera, Marcos. 2017. El triunfo de Trump: Claves Sobre la Nueva Extrema Derecha Norteamericana [Trump’s Triumph: Keys to the New American Extreme Right]. Madrid: Postmetrópolis Editorial. [Google Scholar]

- Robles, Gustavo M. 2020. El fin de algunas ilusiones: Subjetividad y democracia en tiempos de regresión autoritaria. Resistances. Journal of the Philosophy of History 1: 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roco-Videla, Ángel, Raúl Aguilera-Eguía, and Mariela Olguin-Barraza. 2024. Ventajas del uso del coeficiente de omega de McDonald frente al alfa de Cronbach. Nutrición Hospitalaria 41: 262–63. [Google Scholar]

- Rolnik, Suely. 2019. Esferas de la Insurrección. Apuntes para Descolonizar el Inconsciente. Buenos Aires: Tinta Limón Ediciones. [Google Scholar]

- Russo, Silvia, Alberto Mirisola, Francesca Dallago, and Michele Roccato. 2020. Facing natural disasters through the endorsement of authoritarian attitudes. Journal of Environmental Psychology 68: 101412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, Matthew D. 2019. Interrogating ‘authoritarian neoliberalism’: The problem of periodization. Competition & Change 23: 116–37. [Google Scholar]

- Saidel, Matías. 2021. El neoliberalismo autoritario y el auge de las nuevas derechas. História Unisinos 25: 263–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidel, Matías. 2023. Neoliberalism Reloaded: Authoritarian Governmentality and the Rise of the Radical Right. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, vol. 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schermelleh-Engel, Karin, Helfried Moosbrugger, and Hans Müller. 2003. Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods of Psychological Research Online 8: 23–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son Hing, Leanne S., Ramona Bobocel, Mark P. Zanna, and Maxine V. McBride. 2007. Authoritarian dynamics and unethical decision making: High social dominance orientation leaders and high right-wing authoritarianism followers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 92: 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubbs, Paul, and Noémi Lendvai-Bainton. 2020. Authoritarian neoliberalism, radical conservatism and social policy within the European Union: Croatia, Hungary and Poland. Development and Change 51: 540–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugarman, Jeff. 2015. Neoliberalism and psychological ethics. Journal of theoretical and Philosophical Psychology 35: 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tansel, Cemal B., ed. 2017. States of Discipline: Authoritarian Neoliberalism and the Contested Reproduction of Capitalist Order. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Traverso, Enzo. 2019. Las Nuevas Caras de la Derecha [The New Faces of the Right]. Córdoba: Siglo XXI Argentina. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veiga, Francisco, Carlos González-Villa, Steven Forti, Alfredo Sasso, Jelena Prokopljevic, and Ramón Moles. 2019. Patriotas indignados: Sobre la nueva ultraderecha en la Posguerra Fría. Neofascismo, Posfascismo y Nazbols. Madrid: Alianza Editorial. [Google Scholar]

- Vilanova, Felipe, Taciano L. Milfont, Clara Cantal, Silvia H. Koller, and Ângelo B. Costa. 2020. Evidence for Cultural Variability in Right-Wing Authoritarianism Factor Structure in a Politically Unstable Context. Social Psychological and Personality Science 11: 658–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, Max. 2012. La ética Protestante y el “Espíritu” del Capitalismo [The Protestant Ethic and the “Spirit” of Capitalism]. Madrid: Alianza Editorial. First published 1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegelin, Lucía, and Micaela B. Alquezar. 2021. Hacia una epistemología crítica del neoliberalismo autoritario: N. Fraser, M. Cooper y W. Brown en discusión. Argumentos. Revista de Crítica Social 24: 430–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weise, David R., Thomas Arciszewski, Jean-François Verlhiac, Tom Pyszczynski, and Jeff Greenberg. 2012. Terror management and attitudes toward immigrants: Differential effects of mortality salience for low and high right-wing authoritarians. European Psychologist 17: 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Glenn D., and John R. Patterson. 1968. A new measure of conservatism. British Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 7: 264–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Marc S. 2003. Social dominance and ethical ideology: The end justifies the means? The Journal of Social Psychology 143: 549–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Womick, Jake, Brendon Woody, and Laura A. King. 2022. Religious fundamentalism, right-wing authoritarianism, and meaning in life. Journal of Personality 90: 277–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žižek, Slavoj. 2012. En Defensa de la Intolerancia. Houston: Sequitur. [Google Scholar]

| Conservative-Moral Axis | Political Axis | Labor Axis |

|---|---|---|

| Family-oriented role and politicization of religion | In line with far-right parties and their security-focused discourse on immigration and belligerence on social media | Conversion of the worker into a self-employed entrepreneur and the role of meritocracy |

| Alliance between neoliberalism and neoconservatism | Cultural nationalism that shifts the focus away from economic issues | Anthropological mutation: from the subject-who-works to the subject-who-lives-to-work |

| Expansion of Hayek’s “protected personal sphere” | Constant threat of a “common enemy” that justifies the Security State | Subject of performance, “entrepreneur of oneself”, doomed to excess (always more) |

| The welfare state is replaced by the nuclear family (Western-Eurocentric) | Scapegoats: Muslims, immigrants, feminism, and the radical left (communism) | Dissolution of time and space: the boundaries between work and leisure are blurred (you work at home; you are like at home at work) |

| Religious politicization: the new spirit of capitalism (Weber) reflected in religious activism, mainly through Evangelical neo-Pentecostal doctrines | Belligerent cyberpolitics on social media: trolling and politically incorrect discourse, fake news, conspiracy theories, memes associated with the American alt-right | Only productive work, not reproductive work |

| Meritocracy: “government of the winners” linked to Foucault’s idea of the “entrepreneur of oneself,” where freedom and autonomy go hand in hand with the demands of performance, flexibility, and adaptability. A supposedly post-prejudice state in which one’s fortune depends exclusively on one’s own effort and ability, so that failure is the result of personal inadequacy rather than structural injustices (Bay-Cheng et al. 2015) | ||

| Relationship with the Just World Theory (Lerner 1980) and the System Justification Theory (Jost et al. 2004) |

| Component | % Variance | % Accumulate Variance |

|---|---|---|

| Authoritarian Aggression | 41.688 | 41.688 |

| Conventionalism | 9.845 | 51.534 |

| Neoliberalism | 7.382 | 58.916 |

| Authoritarian Submission | 5.670 | 64.586 |

| Item | Authoritarian Aggression | Conventionalism | Neoliberalism | Authoritarian Submission |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. People live in a world where everyone, usually, gets what they deserve. | −0.145 | 0.312 | 0.795 | −0.081 |

| 2. Good morals are only possible through religious education, which should be taught in every school. | 0.083 | 0.743 | −0.045 | 0.130 |

| 3. I believe that the current political “benevolence” is impeding the application of harsher but necessary measures to maintain social order. | 0.578 | 0.113 | 0.225 | 0.231 |

| 4. Parents should be strict with their children to ensure they comply to the rules. | 0.151 | −0.016 | −0.180 | 0.842 |

| 5. State subsidies make people lazy and careless. | 0.492 | −0.055 | 0.240 | 0.293 |

| 6. Most of the MENAs (Unaccompanied Foreign Minors) who arrive in our country are involved in delinquency. | 0.606 | 0.351 | 0.041 | 0.085 |

| 7. Everything was easier before globalization. | −0.225 | 0.704 | 0.111 | 0.057 |

| 8. To help our country’s economy, the State should remove barriers to the free movement of the markets. | 0.076 | −0.254 | 0.747 | 0.161 |

| 9. Only the union between a man and a woman should be called marriage. | 0.196 | 0.786 | 0.043 | −0.088 |

| 10. I am in favor of multiculturalism (the presence of diverse cultures) in our country. | 0.252 | 0.687 | −0.139 | 0.140 |

| 11. Obedience and respect for authority are the fundamental pillars of children’s education. | −0.003 | 0.160 | 0.034 | 0.774 |

| 12. Too many politicians focus on issues such as gender identity and forget about the labor issue that really concerns me. | 0.557 | 0.182 | 0.176 | 0.122 |

| 13. Those who oppose the authorities should be punished, since they destabilize the social order. | −0.065 | 0.018 | 0.198 | 0.698 |

| 14. I am in favor of austerity measures (reduction in public spending). | 0.398 | −0.011 | 0.624 | −0.132 |

| 15. The authorities should restrict more severely the entrance of foreigners to our country, especially in this period of crisis. | 0.600 | 0.291 | 0.192 | 0.055 |

| 16. Privatized sectors are always of higher quality, because by competing with other sectors, they improve their products and services. | 0.236 | 0.124 | 0.515 | 0.054 |

| 17. I am in favor of implementing the death penalty for certain crimes. | 0.820 | −0.086 | −0.061 | 0.034 |

| 18. What makes people different from each other is their ability to strive to achieve their goals. | 0.025 | −0.007 | 0.530 | 0.272 |

| Model | χ2 | df | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Base model | 3336.037 | 153 | |

| Factorial model | 247.268 | 129 | <0.001 |

| CFI | TLI | IFI | GFI | RMSEA | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.993 | 0.992 | 0.993 | 0.986 | 0.041 | 0.063 |

| Authoritarian Aggression | Neoliberalism | Conventionalism | Authoritarian Submission | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authoritarian Aggression | 1.000 | - | - | - |

| Neoliberalism | 0.865 | 1.000 | - | - |

| Conventionalism | 0.695 | 0.447 | 1.000 | - |

| Authoritarian Submission | 0.700 | 0.718 | 0.557 | 1.000 |

| Factor | Item | Factor Loading | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Authoritarian Aggression | 3 | 0.669 | 0.448 |

| 5 | 0.849 | 0.721 | |

| 6 | 0.728 | 0.530 | |

| 12 | 0.727 | 0.528 | |

| 15 | 0.736 | 0.541 | |

| 17 | 0.610 | 0.372 | |

| Neoliberalism | 1 | 0.498 | 0.248 |

| 8 | 0.554 | 0.307 | |

| 14 | 0.785 | 0.616 | |

| 16 | 0.768 | 0.590 | |

| 18 | 0.669 | 0.447 | |

| Authoritarian Submission | 4 | 0.641 | 0.411 |

| 11 | 0.875 | 0.765 | |

| 13 | 0.629 | 0.396 | |

| Conventionalism | 2 | 0.675 | 0.456 |

| 7 | 0.379 | 0.144 | |

| 9 | 0.875 | 0.765 | |

| 10 | 0.535 | 0.286 |

| Authoritarian Aggression | Neoliberalism | Conventionalism | Authoritarian Submission | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authoritarian Aggression | - | 0.887 | 0.771 | 0.720 |

| Neoliberalism | 0.887 | - | 0.676 | 0.723 |

| Conventionalism | 0.771 | 0.676 | - | 0.636 |

| Authoritarian Submission | 0.720 | 0.723 | 0.636 | - |

| Authoritarian Aggression | Authoritarian Submission | Conventionalism | Neoliberalism | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authoritarian Aggression | - | 0.558 | 0.536 | 0.701 |

| Authoritarian Submission | 0.558 | - | 0.396 | 0.533 |

| Conventionalism | 0.536 | 0.396 | - | 0.411 |

| Neoliberalism | 0.701 | 0.533 | 0.411 | - |

| Factor | Item | Correlation |

|---|---|---|

| Authoritarian Aggression | 3 | 0.697 |

| 5 | 0.777 | |

| 6 | 0.741 | |

| 12 | 0.762 | |

| 15 | 0.751 | |

| 17 | 0.629 | |

| Neoliberalism | 1 | 0.610 |

| 8 | 0.635 | |

| 14 | 0.769 | |

| 16 | 0.771 | |

| 18 | 0.721 | |

| Authoritarian Submission | 4 | 0.805 |

| 11 | 0.850 | |

| 13 | 0.731 | |

| Conventionalism | 2 | 0.536 |

| 7 | 0.678 | |

| 9 | 0.709 | |

| 10 | 0.611 |

| Items | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| Group 1 | 2.63 | 2.08 | 3.69 | 3.07 | 3.66 | 2.86 | 3.06 | 3.21 | 2.79 |

| Group 2 | 2.20 | 1.36 | 3.34 | 2.96 | 2.51 | 2.28 | 2.39 | 2.98 | 1.24 |

| Group 3 | 1.81 | 1.09 | 1.89 | 2.09 | 1.30 | 1.16 | 2.21 | 2.00 | 1.04 |

| Total | 2.20 | 1.49 | 2.94 | 2.69 | 2.44 | 2.06 | 2.53 | 2.71 | 1.64 |

| Items | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

| Group 1 | 2.15 | 3.82 | 4.27 | 3.38 | 3.72 | 3.52 | 3.52 | 3.25 | 4.03 |

| Group 2 | 1.74 | 3.09 | 3.50 | 2.79 | 2.99 | 2.77 | 2.64 | 2.05 | 3.09 |

| Group 3 | 1.25 | 2.01 | 2.30 | 2.05 | 1.86 | 1.52 | 1.41 | 1.25 | 2.12 |

| Total | 1.69 | 2.94 | 3.31 | 2.71 | 2.82 | 2.56 | 2.48 | 2.14 | 3.04 |

| Reactive | Discrimination Coefficient |

|---|---|

| R_1 | 0.393 |

| R_2 | 0.404 |

| R_3 | 0.582 |

| R_4 | 0.461 |

| R_5 | 0.720 |

| R_6 | 0.588 |

| R_7 | 0.255 |

| R_8 | 0.457 |

| R_9 | 0.512 |

| R_10 | 0.316 |

| R_11 | 0.625 |

| R_12 | 0.615 |

| R_13 | 0.466 |

| R_14 | 0.645 |

| R_15 | 0.622 |

| R_16 | 0.606 |

| R_17 | 0.470 |

| R_18 | 0.563 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nicieza-Cueto, E.; Moral-Jiménez, M.d.l.V. Authoritarianism in the 21st Century: A Proposal for Measuring Authoritarian Attitudes in Neoliberalism. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 431. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14070431

Nicieza-Cueto E, Moral-Jiménez MdlV. Authoritarianism in the 21st Century: A Proposal for Measuring Authoritarian Attitudes in Neoliberalism. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(7):431. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14070431

Chicago/Turabian StyleNicieza-Cueto, Esmeralda, and María de la Villa Moral-Jiménez. 2025. "Authoritarianism in the 21st Century: A Proposal for Measuring Authoritarian Attitudes in Neoliberalism" Social Sciences 14, no. 7: 431. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14070431

APA StyleNicieza-Cueto, E., & Moral-Jiménez, M. d. l. V. (2025). Authoritarianism in the 21st Century: A Proposal for Measuring Authoritarian Attitudes in Neoliberalism. Social Sciences, 14(7), 431. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14070431