The Race Paradox in Mental Health Among Older Adults in the United States: Examining Social Participation as a Mechanism

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Race Paradox in Mental Health

1.2. Social Participation Among Older Adults

1.3. Social Participation in Older African Americans

1.4. Social Participation and Mental Health Among Older African Americans

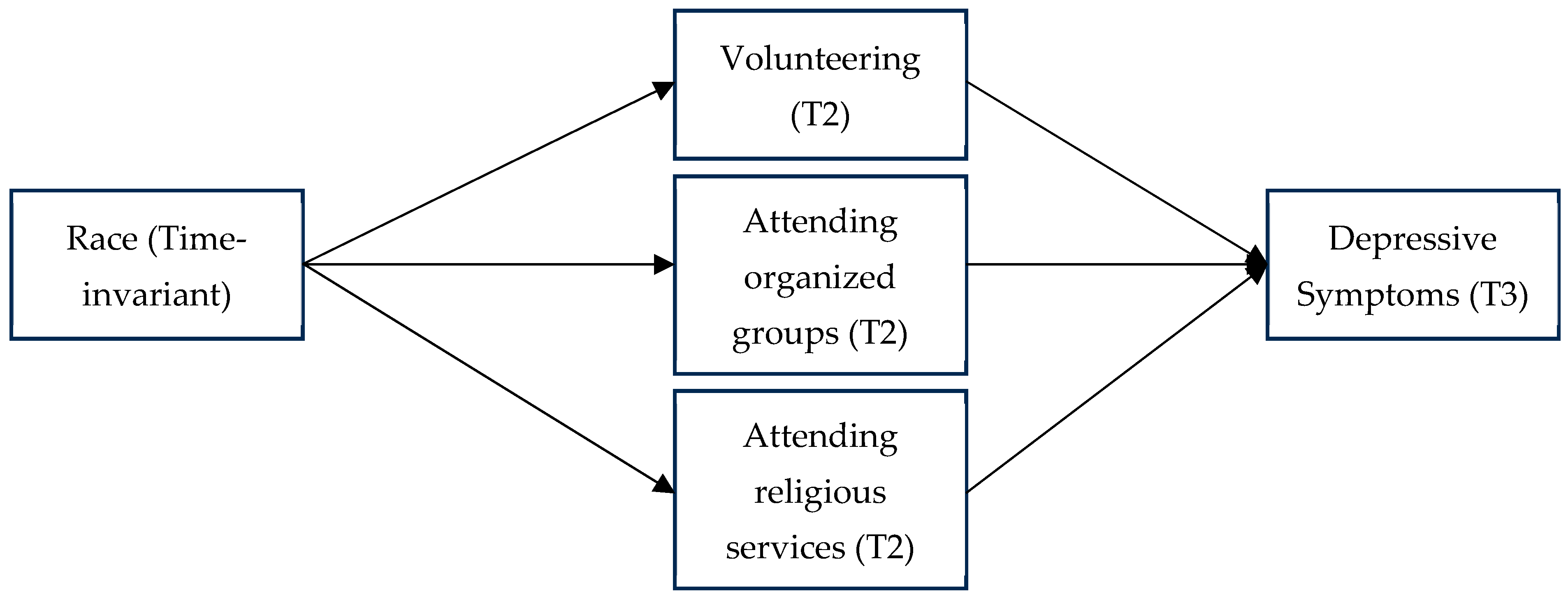

1.5. The Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Measures

2.1.1. Dependent Variable

2.1.2. Independent Variable

2.1.3. Mediators

2.1.4. Covariates

2.2. Analysis Strategy

3. Results

3.1. Univariate and Bivariate Analyses

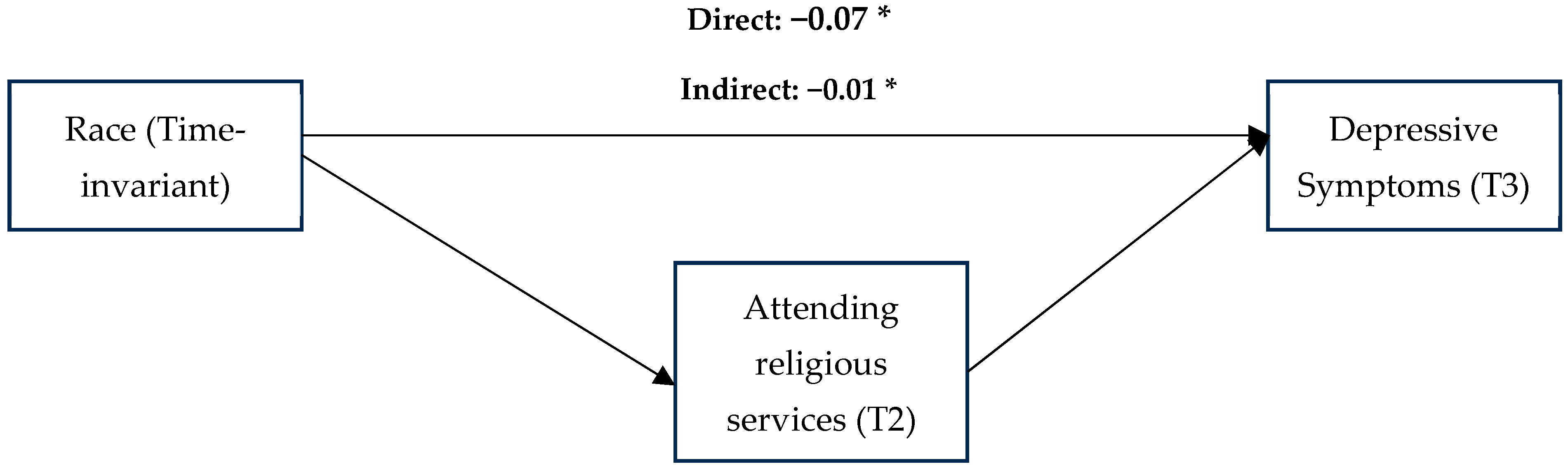

3.2. Main Analyses

4. Discussion

Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Achdut, Netta, and Orly Sarid. 2020. Socio-economic status, self-rated health and mental health: The mediation effect of social participation on early-late midlife and older adults. Israel Journal of Health Policy Research 9: 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Administration for Community Living. 2021. National Family Caregiver Support Program. Available online: https://www.takecare.community/resource/national-family-caregiver-support-program/ (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Agahi, Neda, Carin Lennartsson, Ingemar KÅReholt, and Benjamin A. Shaw. 2013. Trajectories of social activities from middle age to old age and late-life disability: A 36-year follow-up. Age and Ageing 42: 790–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amagasa, Shiho, Noritoshi Fukushima, Hiroyuki Kikuchi, Koichiro Oka, Tomoko Takamiya, Yuko Odagiri, Shigeru Inoue, and Toshiyuki Ojima. 2017. Types of social participation and psychological distress in Japanese older adults: A five-year cohort study. PLoS ONE 12: e0175392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aten, Jamie D., David M. Boan, John M. Hosey, Sharon Topping, Alice Graham, and Hannah Im. 2013. Building capacity for responding to disaster emotional and spiritual needs: A clergy, academic, and mental health partnership model (CAMP). Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy 5: 591. [Google Scholar]

- Bertera, Elizabeth M., and Barbara Bailey-Etta. 2001. Physical dysfunction and social participation among racial/ethnic groups of older Americans: Implications for social work. Social Thought 20: 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolin, Kristian, Björn Lindgren, Martin Lindström, and Paul Nystedt. 2003. Investments in social capital—Implications of social interactions for the production of health. Social Science & Medicine 56: 2379–90. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen, Kenneth A., Stephen J. Tueller, and Daniel Oberski. 2013. Issues in the structural equation modeling of complex survey data. Paper presented at 59th World Statistics Congress, Hong Kong, August 25–30; Available online: http://2013.isiproceedings.org/Files/STS010-P1-S.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2024).

- Bourassa, Kyle J., Molly Memel, Cindy Woolverton, and David A. Sbarra. 2017. Social participation predicts cognitive functioning in aging adults over time: Comparisons with physical health, depression, and physical activity. Aging & Mental Health 21: 133–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1986. The Forms of Capital. In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education. Edited by John Richardson. New York: Greenwood, pp. 241–258. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Tony N., David R. Williams, James S. Jackson, Harold W. Neighbors, Myriam Torres, Sherrill L. Sellers, and Kendrick T. Brown. 2000. “Being black and feeling blue”: The mental health consequences of racial discrimination. Race and Society 2: 117–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchman, Aron S., Lei Yu, Patricia A. Boyle, Julie A. Schneider, Philip L. De Jager, and David A. Bennett. 2016. Higher brain BDNF gene expression is associated with slower cognitive decline in older adults. Neurology 86: 735–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, Laura L., Derek M. Isaacowitz, and Susan T. Charles. 1999. Taking time seriously. A theory of socioemotional selectivity. The American Psychologist 54: 165–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatters, Linda M., Ann W Nguyen, and Robert Joseph Taylor. 2014. Religion and spirituality among older African Americans, Asians, and Hispanics. In Handbook of Minority Aging. Edited by Keith E. Whitfield, Tamara A. Baker, Cleopatra M. Abdou, Jacqueline L. Angel, Linda A. Chadiha, Kimberly Gerst-Emerson, James S. Jackson, Kyriakos S. Markides, Peggy A. Rozario and Ronald J. Thorpe, Jr. New York: Springer Publishing Company, pp. 47–64. [Google Scholar]

- Chatters, Linda M., Jacqueline S. Mattis, Amanda Toler Woodward, Robert Joseph Taylor, Harold W. Neighbors, and Nyasha A. Grayman. 2011. Use of ministers for a serious personal problem among African Americans: Findings from the National Survey of American Life. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 81: 118–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatters, Linda M., Kai McKeever Bullard, Robert Joseph Taylor, Amanda Toler Woodward, Harold W. Neighbors, and James S. Jackson. 2008. Religious participation and DSM-IV disorders among older African Americans: Findings from the National Survey of American Life. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 16: 957–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatters, Linda M., Robert Joseph Taylor, Amanda Toler Woodward, and Emily J. Nicklett. 2015. Social support from church and family members and depressive symptoms among older African Americans. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 23: 559–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatters, Linda M., Robert Joseph Taylor, and Karen D. Lincoln. 1999. African American religious participation: A multi-sample comparison. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 38: 132–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Eunsoo, Kyu-Man Han, Jisoon Chang, Youn Jung Lee, Kwan Woo Choi, Changsu Han, and Byung-Joo Ham. 2021. Social participation and depressive symptoms in community-dwelling older adults: Emotional social support as a mediator. Journal of Psychiatric Research 137: 589–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Sunha. 2020. The Effects of Social Participation Restriction on Psychological Distress among Older Adults with Chronic Illness. Journal of Gerontological Social Work 63: 850–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Sunha. 2023. Association of hearing impairment with social participation restriction and depression: Comparison between midlife and older adults. Aging & Mental Health 27: 2257–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, Rachel G., Tim D. Windsor, and Mary A. Luszcz. 2017. Perceived control moderates the effects of functional limitation on older adults’ social activity: Findings from the Australian Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 72: 571–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egeljić-Mihailović, Nataša, Nina Brkić-Jovanović, Tatjana Krstić, Dragana Simin, and Dragana Milutinović. 2022. Social participation and depressive symptoms among older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic in Serbia: A cross-sectional study. Geriatric Nursing 44: 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayman, Mathew D., Andrew M. Cislo, Alexa R. Goidel, and Koji Ueno. 2014. SES and race-ethnic differences in the stress-buffering effects of coping resources among young adults. Ethnicity & Health 19: 198–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, Ernest, Huei-Wern Shen, Yi Wang, Linda Sprague Martinez, and Julie Norstrand. 2016. Race and place: Exploring the intersection of inequity and volunteerism among older black and white adults. Journal of Gerontological Social Work 59: 381–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffith, Lauren E., Parminder Raina, Mélanie Levasseur, Nazmul Sohel, Hélène Payette, Holly Tuokko, Edwin van Den Heuvel, Andrew Wister, Anne Gilsing, Christopher Patterson, and et al. 2017. Functional disability and social participation restriction associated with chronic conditions in middle-aged and older adults. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 71: 381–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Lizhi, Fengping Luo, Ningcan Gao, and Bin Yu. 2021. Social isolation and cognitive decline among older adults with depressive symptoms: Prospective findings from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics 95: 104390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haslam, Catherine, Tegan Cruwys, S. Alexander Haslam, and Jolanda Jetten. 2015. Social connectedness and health. Encyclopedia of Geropsychology 46: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, Lindsay V. 2020. Hybrid Networks of Practice: How Online Spaces Extend Faith-Based Communities of Practice. University Park: The Pennsylvania State University. [Google Scholar]

- He, Qian, Yanjie Cui, Ling Liang, Qi Zhong, Jie Li, Yuancheng Li, Xiaofeng Lv, and Fen Huang. 2017. Social participation, willingness and quality of life: A population-based study among older adults in rural areas of China. Geriatrics & Gerontology International 17: 1593–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill-Joseph, Eundria A. 2019. Coping while Black: Chronic illness, mastery, and the Black-White health paradox. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 6: 935–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinterlong, James E. 2006. Race disparities in health among older adults: Examining the role of productive engagement. Health & Social Work 31: 275–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, E. Alison, Dana Rose Garfin, Pauline Lubens, and Roxane Cohen Silver. 2020. Media Exposure to Collective Trauma, Mental Health, and Functioning: Does It Matter What You See? Clinical Psychological Science 8: 111–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Li-Tze, and Peter M. Bentler. 1999. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling 6: 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, Michael, and David H. Demo. 1989. Self-perceptions of Black Americans: Self-esteem and personal efficacy. American Journal of Sociology 95: 132–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, Tiffany F., Jason D. Flatt, Bo Fu, Chung-Chou H. Chang, and Mary Ganguli. 2013. Engagement in social activities and progression from mild to severe cognitive impairment: The MYHAT study. International Psychogeriatrics 25: 587–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irani, E., Fei Wang, Kylie Meyer, Sarah E. Moore, and Kai Ding. 2024. Social activity restriction and psychological health among caregivers of older adults with and without dementia. Journal of Aging and Health 36: 678–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, Kimberly J., and S. Hannah Lee. 2017. Factors associated with volunteering among racial/ethnic groups: Findings from the California Health Interview Survey. Research on Aging 39: 575–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaMotte, Megan E., Marta Elliott, and Dawne M. Mouzon. 2023. Revisiting the black-white mental health paradox during the coronavirus pandemic. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 10: 2802–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Hyo Young, Soong-Nang Jang, Seonja Lee, Sung-Il Cho, and Eun-Ok Park. 2008. The relationship between social participation and self-rated health by sex and age: A cross-sectional survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies 45: 1042–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Samsik, and Hyojin Choi. 2020. Impact of older adults’ mobility and social participation on life satisfaction in South Korea. Asian Social Work and Policy Review 14: 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, Curtis S., William B. Whitney, Jean Un, Jennifer S. Payne, Maria Simanjuntak, Stephen Hamilton, Tsegamlak Worku, and Nathaniel A. Fernandez. 2022. Hospitality towards people with Mental Illness in the Church: A cross-cultural qualitative study. Pastoral Psychology 71: 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Tené T., Courtney D. Cogburn, and David R. Williams. 2015. Self-reported experiences of discrimination and health: Scientific advances, ongoing controversies, and emerging issues. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 11: 407–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Chunkai, Shan Jiang, Na Li, and Qiunv Zhang. 2018. Influence of social participation on life satisfaction and depression among Chinese elderly: Social support as a mediator. Journal of Community Psychology 46: 345–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Hsien-Chang, Yi-Han Hu, Adam E. Barry, and Alex Russell. 2020. Assessing the associations between religiosity and alcohol use stages in a representative US sample. Substance Use & Misuse 55: 1618–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longacre, Margaret L., Vivian G. Valdmanis, Elizabeth A. Handorf, and Carolyn Y. Fang. 2017. Work Impact and Emotional Stress Among Informal Caregivers for Older Adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 72: 522–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louie, Patricia, and Blair Wheaton. 2019. The Black-White paradox revisited: Understanding the role of counterbalancing mechanisms during adolescence. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 60: 169–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louie, Patricia, Laura Upenieks, Christy L. Erving, and Courtney S. Thomas Tobin. 2022. Do racial differences in coping resources explain the Black–White paradox in mental health? A test of multiple mechanisms. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 63: 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackenzie, Corey S., and Shahad Abdulrazaq. 2021. Social engagement mediates the relationship between participation in social activities and psychological distress among older adults. Aging & Mental Health 25: 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes de Leon, Carlos F. Mendes, Thomas A. Glass, and Lisa F. Berkman. 2003. Social engagement and disability in a community population of older adults: The New Haven EPESE. American Journal of Epidemiology 157: 633–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, Ilan H. 2003. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin 129: 674–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouzon, Dawne M. 2013. Can family relationships explain the race paradox in mental health? Journal of Marriage and Family 75: 470–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouzon, Dawne M. 2014. Relationships of choice: Can friendships or fictive kinships explain the race paradox in mental health? Social Science Research 44: 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouzon, Dawne M. 2017. Religious involvement and the Black–White paradox in mental health. Race and Social Problems 9: 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. 2020. Preventing Elder Abuse. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/elder-abuse/about/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/elderabuse/fastfact.html (accessed on 15 February 2024).

- Nguyen, Ann W. 2020. Religion and mental health in racial and ethnic minority populations: A review of the literature. Innovation in Aging 4: igaa035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedzwiedz, Claire L., Elizabeth A. Richardson, Helena Tunstall, Niamh K. Shortt, Richard J. Mitchell, and Jamie R. Pearce. 2016. The relationship between wealth and loneliness among older people across Europe: Is social participation protective? Preventive Medicine 91: 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyqvist, Fredrica, Anna K. Forsman, Gianfranco Giuntoli, and Mima Cattan. 2013. Social capital as a resource for mental well-being in older people: A systematic review. Aging & Mental Health 17: 394–410. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney, Jean S. 2010. The multigroup ethnic identity measure (MEIM). Encyclopedia of Cross-Cultural School Psychology 1: 642–43. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, Juliana Martins, and Anita Liberalesso Neri. 2017. Trajectories of social participation in old age: A systematic literature review. Revista Brasileira De Geriatria E Gerontologia 20: 259–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radloff, Lenore S. 1977. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement 1: 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers-Jarrell, Tia. 2018. Through Their Eyes: Exploring Older Adults’ Experiences with an Intergenerational Project. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10464/13572 (accessed on 15 February 2024).

- Santini, Ziggi Ivan, Line Nielsen, Carsten Hinrichsen, Charlotte Meilstrup, Ai Koyanagi, Josep Maria Haro, Robert J. Donovan, and Vibeke Koushede. 2018. Act-Belong-Commit Indicators Promote Mental Health and Wellbeing among Irish Older Adults. American Journal of Health Behavior 42: 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santini, Ziggi Ivan, Paul E Jose, Erin York Cornwell, Ai Koyanagi, Line Nielsen, Carsten Hinrichsen, Charlotte Meilstrup, Katrine R Madsen, and Vibeke Koushede. 2020. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and symptoms of depression and anxiety among older Americans (NSHAP): A longitudinal mediation analysis. The Lancet Public Health 5: e62–e70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifian, Neika, and Daniel Grühn. 2019. The differential impact of social participation and social support on psychological well-being: Evidence from the Wisconsin longitudinal study. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development 88: 107–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyth, Natasha, Chesmal Siriwardhana, Matthew Hotopf, and Stephani L. Hatch. 2015. Social networks, social support and psychiatric symptoms: Social determinants and associations within a multicultural community population. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 50: 1111–20. [Google Scholar]

- Sobel, Michael E. 1987. Direct and indirect effects in linear structural equation models. Sociological Methods & Research 16: 155–76. [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. 2013. Stata: Manual 13. Available online: https://www.stata.com/manuals13/iglossary.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2024).

- Tang, Fengyan, Valire Carr Copeland, and Sandra Wexler. 2012. Racial differences in volunteer engagement by older adults: An empowerment perspective. Social Work Research 36: 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas Tobin, Courtney S. Thomas, Christy L. Erving, Taylor W. Hargrove, and Lacee A. Satcher. 2022. Is the Black-White mental health paradox consistent across age, gender, and psychiatric disorders? Aging & Mental Health 26: 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiernan, Chad, Cathy Lysack, Stewart Neufeld, and Peter A. Lichtenberg. 2013. Community engagement: An essential component of well-being in older African-American adults. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development 77: 233–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. 2019. World Population Ageing 2019: Highlights (ST/ESA/SER.A/430). New York: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. [Google Scholar]

- Upenieks, Laura. 2023. Unpacking the Relationship Between Prayer and Anxiety: A Consideration of Prayer Types and Expectations in the United States. Journal of Religion and Health 62: 1810–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaingankar, Janhavi Ajit, Siow Ann Chong, Edimansyah Abdin, Louisa Picco, Anitha Jeyagurunathan, YunJue Zhang, Rajeswari Sambasivam, Boon Yiang Chua, Li Ling Ng, Martin Prince, and et al. 2016. Care participation and burden among informal caregivers of older adults with care needs and associations with dementia. International Psychogeriatrics 28: 221–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velez, Brandon L., Laurel B. Watson, Robert Cox, Jr., and Mirella J. Flores. 2017. Minority stress and racial or ethnic minority status: A test of the greater risk perspective. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity 4: 257. [Google Scholar]

- Wanchai, Ausanee, and Duangjai Phrompayak. 2019. A Systematic Review of Factors Influencing Social Participation of Older Adults. Pacific Rim International Journal of Nursing Research 23: 131–34. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Fei, Ishita Kapur, Nandita Mukherjee, and Kai Wang. 2025. The mediating effect of social participation restriction on the association between role overload and mental health among caregivers of older adults with dementia. International Journal of Aging and Human Development 100: 227–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, Rebecca M. 2012. Applied Statistics: From Bivariate Through Multivariate Techniques. London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Yip, Tiffany. 2018. Ethnic/Racial Identity—A Double-Edged Sword? Associations with Discrimination and Psychological Outcomes. Current Directions in Psychological Science 27: 170–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total Sample | African American | White | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.62 | |||

| Men | 44.38% (582) | 41.22% (81) | 44.28% (422) | |

| Women | 55.62% (710) | 58.78% (130) | 55.72% (488) | |

| Annual household income | 0.08 | |||

| 0–24,999 | 26% (288) | 37.81% (68) | 22.09% (152) | |

| 25,000–49,999 | 28.36% (249) | 34.06% (38) | 28.81% (191) | |

| 50,000–99,999 | 30.75% (276) | 17.44% (26) | 32.95% (226) | |

| >100,000 | 14.89% (114) | 10.68% (5) | 16.15% (100) | |

| Marital status | <0.001 | |||

| Not Married | 27.72% (420) | 43.82% (112) | 25.79% (258) | |

| Married | 72.28% (872) | 56.18% (99) | 74.21% (652) | |

| Perceived physical health | <0.001 | |||

| Poor to fair | 17.28% (239) | 24.98% (54) | 15.08% (132) | |

| Good | 28.83% (375) | 37.49% (82) | 27.23% (234) | |

| Very good to excellent | 53.89% (673) | 37.53% (73) | 57.68% (542) | |

| Volunteering (0–3) | 1.29 (1.14) | 1.33 (1.16) | 1.36 (1.13) | 0.74 |

| Organized groups (0–3) | 1.52 (1.17) | 1.61 (1.19) | 1.58 (1.15) | 0.73 |

| Religious services (0–3) | 1.92 (1.22) | 2.29 (1.04) | 1.82 (1.26) | <0.001 |

| Depressive symptoms (11–44) | 15.78 (4.77) | 16.51 (4.65) | 15.46 (4.57) | <0.01 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | ||||

| Depressive Symptoms | Volunteering | Depressive Symptoms | Organized Groups | Depressive Symptoms | Religious Services | Depressive Symptoms | |

| Race (ref = White) | |||||||

| African American | −0.07 (0.47) ** | −0.04 (0.03) | −0.08 (0.03) ** | −0.03 (0.04) | −0.08 (0.02) *** | 0.10 (0.03) *** | −0.07 (0.03) * |

| Covariates | |||||||

| Gender (ref = Male) | |||||||

| Female | 0.05 (0.35) | 0.02 (0.05) | 0.07 (0.04) * | 0.08 (0.04) | 0.07 (0.04) | 0.09 (0.05) | 0.08 (0.04) * |

| Marital status (ref = not married) | |||||||

| Married | −0.01 (0.39) | −0.10 (0.04) * | −0.01 (0.04) | −0.09 (0.04) * | −0.01 (0.04) | 0.13 (0.04) ** | 0.01 (0.03) |

| Household income (ref = <25,000) | |||||||

| 25,000–49,999 | 0.02 (0.49) | −0.01 (0.05) | 0.00 (0.06) | −0.03 (0.05) | −0.00 (0.06) | −0.12 (0.05) * | −0.01 (0.06) |

| 50,000–99,999 | 0.06 (0.50) | 0.03 (0.06) | 0.03 (0.07) | 0.08 (0.06) | 0.03 (0.07) | −0.08 (0.06) | 0.02 (0.07) |

| >100,000 | 0.03 (0.60) | 0.03 (0.05) | 0.00 (0.06) | 0.10 (0.06) | 0.01 (0.06) | −0.19 (0.06) ** | −0.02 (0.05) |

| Perceived physical health (ref = poor to fair) | |||||||

| Good | −0.03 (0.59) | 0.17 (0.05) *** | −0.08 (0.05) | 0.14 (0.06) * | −0.08 (0.05) | 0.11 (0.06) * | −0.07 (0.05) |

| Very good to excellent | −0.14 (0.56) ** | 0.26 (0.05) *** | −0.22 (0.05) *** | 0.20 (0.06) ** | −0.22 (0.05) *** | 0.14 (0.06) * | −0.21 (0.05) *** |

| Depressive symptoms (T1) | 0.29 (0.06) *** | −0.07 (0.05) | - | −0.08 (0.05) | - | −0.09 (0.04) * | - |

| Depressive symptoms (T2) | 0.36 (0.06) *** | - | 0.49 (0.04) *** | - | 0.49 (0.04) *** | - | 0.49 (0.04) *** |

| Mediators | |||||||

| Volunteering | - | - | −0.06 (0.03) | - | - | - | - |

| Organized groups | - | - | - | - | −0.07 (0.03) * | - | - |

| Religious services | - | - | - | - | - | - | −0.11 (0.02) *** |

| Total effect | - | −0.08 (0.48) ** | −0.08 (0.48) ** | −0.08 (0.48) ** | |||

| Indirect effect | - | 0.00 (0.04) | 0.00 (0.03) | −0.01 (0.08) * | |||

| Proportion of total effect mediated | - | - | - | 14% | |||

| Complex design df | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 | |||

| N | 710 | 710 | 710 | 710 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, F.; Forrest-Bank, S.; Lou, Y.; Mukherjee, N.; Heo, Y. The Race Paradox in Mental Health Among Older Adults in the United States: Examining Social Participation as a Mechanism. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 426. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14070426

Wang F, Forrest-Bank S, Lou Y, Mukherjee N, Heo Y. The Race Paradox in Mental Health Among Older Adults in the United States: Examining Social Participation as a Mechanism. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(7):426. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14070426

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Fei, Shandra Forrest-Bank, Yifan Lou, Namrata Mukherjee, and Yejin Heo. 2025. "The Race Paradox in Mental Health Among Older Adults in the United States: Examining Social Participation as a Mechanism" Social Sciences 14, no. 7: 426. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14070426

APA StyleWang, F., Forrest-Bank, S., Lou, Y., Mukherjee, N., & Heo, Y. (2025). The Race Paradox in Mental Health Among Older Adults in the United States: Examining Social Participation as a Mechanism. Social Sciences, 14(7), 426. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14070426