Bi5: An Autoethnographic Analysis of a Lived Experience Suicide Attempt Survivor Through Grief Concepts and ‘Participant’ Positionality in Community Research

Abstract

“Let none of you wish for death because of a calamity that has befallen him. But if he must wish for something, let him say: ‘O Allah, keep me alive as long as life is better for me, and cause me to die when death is better for me.’”—[Sahih al-Bukhari 5671, Sahih Muslim 2680]

1. Introduction

1.1. Significance: Theory, Methodology, and Demography

1.2. Background and Context

1.3. On Grief

1.4. On Suicide, Suicidality, and Violence: Terminology Matters

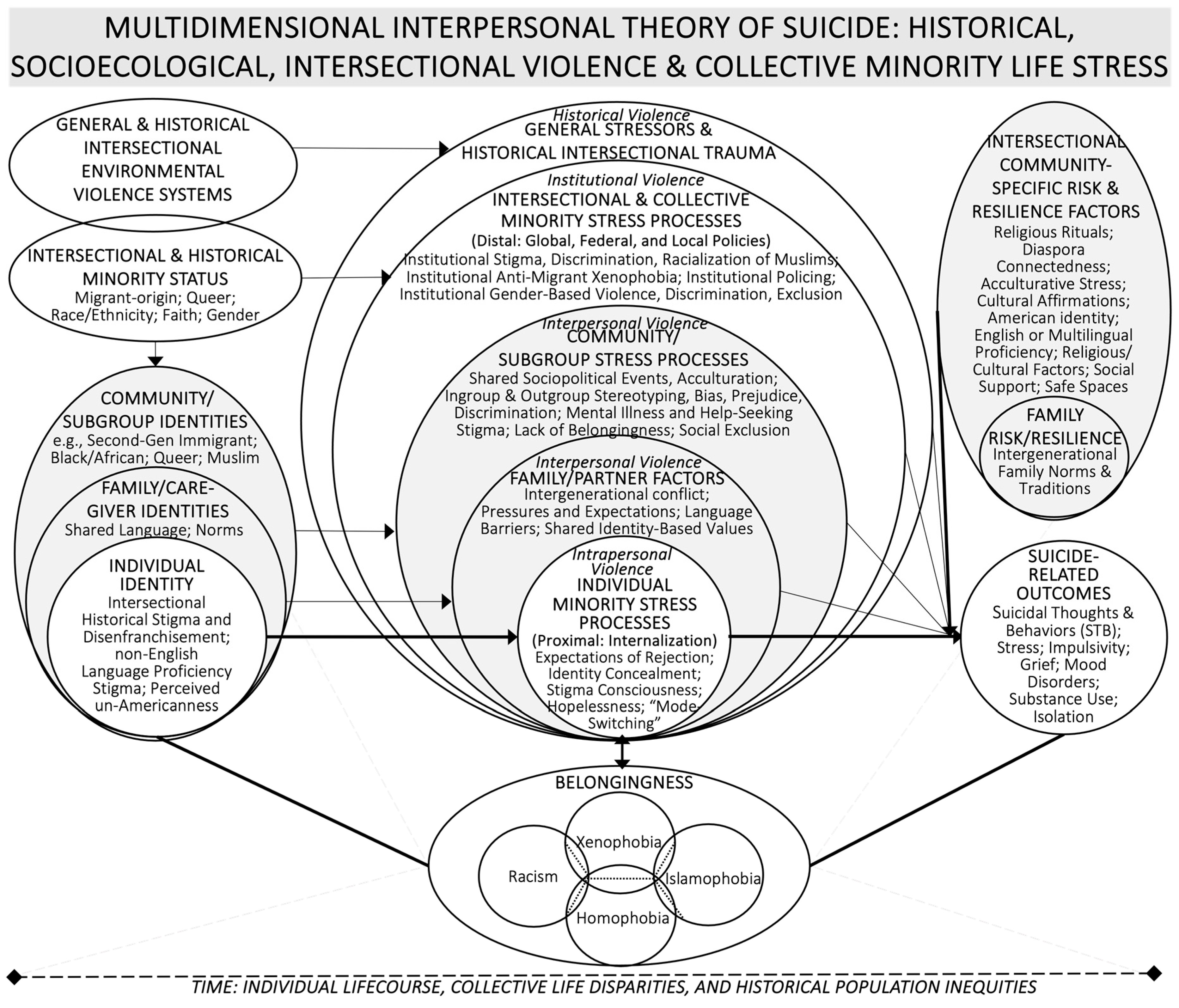

1.5. Theoretical Framework and Conceptual Model

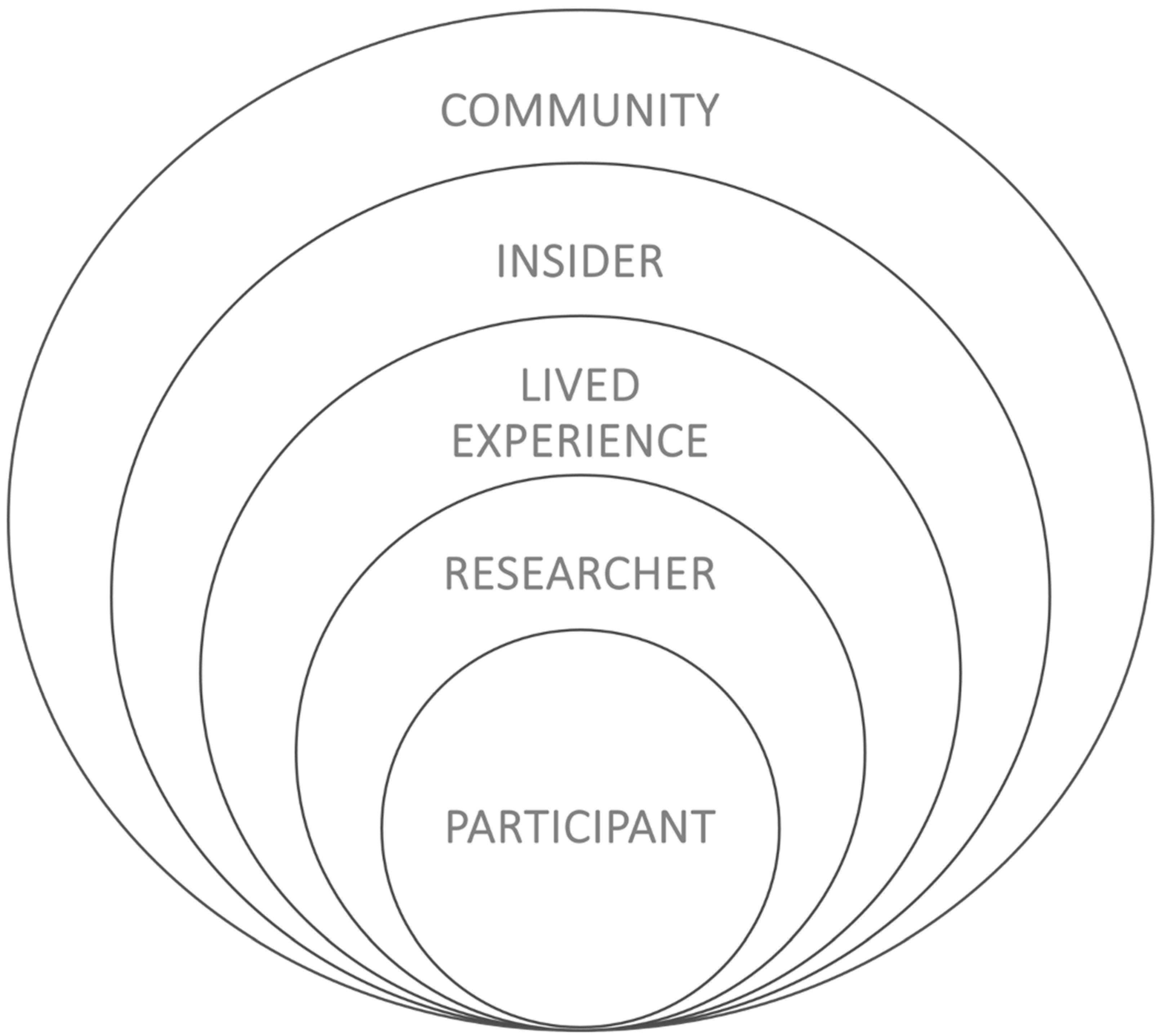

1.6. Positionality Statement

2. On Identifying Multidimensionally as “Bi-___” as Analyzed Through Disenfranchised Grief

2.1. Excerpt: Bi1

Where do I go to feel seen? I was born and raised in sunny Southern California as a second-generation immigrant. My parents come from Bihar, India. Should I act Pakistani, Muslim, brown, American—full-time—or just channel whatever frequency occurs momentarily?Could I share common feelings with people who identify as biracial? Which societies would outcast me if I came out as a genderfluid non-binary woman? What makes disclosing bipolar depression a question of morality and ethics: to institutions, colleagues, friends, human subjects?Where is my camouflage today, do I modify it to ‘pass’ or adapt? How will I know my identity is celebrated, not stigmatized, across time and dynamic social networks? Is my lived experience the embodiment of stigma as a fundamental cause of health inequity?

Can empirical evidence attest I am not the only one feeling this way? Would my faith community support my scientific views? Would the scientific community support my spiritual views? Who can I trust? How could personal narratives sustain and promote empowered lives in diverse populations?Why does such a great task befall me? My life mission…to reclaim humanity? I am disabled; I need more spoons.1 Living means so much more. Should I hope for a better afterlife? Will my hope run out? End this isolation, I can’t take it anymore! I pray for peace in all souls.

2.2. Bi1 Analysis: Disenfranchised Grief

3. On Identifying Beyond the Binary as Analyzed Through Ambiguous Loss

3.1. Excerpt: Bi2 as Genderfluid Non-Binary

2008 would be the birth year for some early adults who are age 15 today. That was a monumental year for so many reasons. As was customary in my older sister’s household, we discussed most matters openly. California’s Prop 8 was distressingly instigated. “I am not a member of that community, so I didn’t vote on it,” I gently protested. I felt courage to speak up on the matter but suppressed my pain simultaneously. It happened to be the first year I was eligible to vote as I had just turned 18.Why do I feel such injustice when my loved ones speak against civil rights for queer people? I just know what it feels like to experience crippling discrimination and I relate to having no idea who or what is safe to ‘be’ around. Now, in 2023, the conversation has evolved, as have I. Ironically, Muslim elders and Islamic teachings led to me embracing my queer vibes. During a session with my spouse around 2019, our Black Muslim marital therapist conveyed she sensed a strong masculine energy from me. I was taken aback.Last year, I encountered messaging on Instagram from a nonprofit organization called HEART. It talked about two of the 99 names of Allah. Names describing God as “compassionate” derive from the Arabic term for “womb.” In fact, it is a divine characteristic of God to be outside social constructs such as gender. He is not “he.” Is this affirmation what I had been looking for all along? Finally, I get it, I am enby, genderfluid, too, as a parent, a mom. Many creations gender bend for survival. The Creator divinely fashioned me.God makes no mistakes. God says “Be! and it is.” So, I am.

3.2. Analysis: Ambiguous Loss

Even for those trans persons who do not transition from one sex category to another, moving to a more gender-fluid identity involves a shift away from one if not clearly toward another. For family members, transition brings about a renegotiation of meaning regarding the trans person’s identity, which often incites ambiguous loss. This loss is related to contradiction in the meaning making process resulting in the perception that the trans person is both present and absent, the same and different.

3.3. On Gender and Suicide

4. On Identifying as a Patient with a Post-Partum Bipolar Diagnosis as Analyzed Through Anticipatory Grief

4.1. Excerpt: Bi3 as Bipolar

What use is my lived experience to a psychiatrist? As a young person, I felt gaslighted when I would bring up issues that affect my daily life to clinicians. It could be their unintended ignorance, or bias. I spent so many years perseverating, feeling suicidal ruminating over how powerless I felt. Will I grow cancer in my throat because I have grown accustomed to self-censorship for my own survival? When I do speak up, why does it sound like I’m the crazy one?How do I know whether your diagnosis of me pathologizes discrimination? Are you sure it wasn’t racism-based traumatic stress that twisted the mind of my father, Mohammad, into schizophrenia? Is it adjustment disorder still adjusting since his arrival in the 80s? How do I know I can trust you when diagnostic classifications derive from ungeneralizable samples who do not represent me or my life?Will my voice count to the medical establishment if I speak in scientific terms? I reclaim power with conviction and diction to describe paranoia or hypervigilance as normal reactions to surviving historically oppressive systems. My world-renowned advisor stated that women of color are disproportionately diagnosed as bipolar. Most psychiatrists and psychologists cannot relate to my disabled, nonconforming, racialized lived experience. At 29 years old, I roll into the hospital of my home institution—the finest in the world—a pregnant patient in a wheelchair. A white nurse speaks to me in Spanish, racializing me as the kind of brown I am not.I catch myself feeling triggered. I realize I don’t need to be triggered, but now our dynamic becomes racialized. Postpartum, I go back for a routine 6-week checkup. It’s July 2020. I inform the midwife I am symptomatic of psychosis. What? “Psychosis.” She gaped into my eyes, unaware of protocol. Later, policemen show up and forcefully take me away to the hospital by court order. It’s a ‘voluntary’ hospitalization, they tell me to say…

4.2. Analysis: Anticipatory Grief

4.3. On Mental Illness and Suicide

5. On Identifying with Biracial Dualities as Analyzed Through Secondary Loss

5.1. Excerpt: Bi4 as Biracial

Race is socially constructed, right? That’s why Muslims are racialized despite being a faith group. My adolescent years were spent at the Islamic Center of Irvine, where undercover FBI Agent Craig Monteilh infiltrated our Southern California mosque, posing as a new convert, unlawfully targeted our community, abused our sacred spaces, and violated us. (Rafei 2021) We are so often surveilled by undercover agents that I was abnormally distrustful of my own ex-spouse before marrying; he identifies as a convert.Who counts as Muslim? The answer varies depending on who is asking. FBI? CIA? TSA? Matchmaking aunties? Remarkably, even Muslims don’t agree on who is Muslim. I feel intuitively connected to racialized dualisms of belongingness. I am an insider as a Muslim yet an outsider as American. Or is it the other way around? I could be President, but I am not American enough. Even my own South Asian family ridiculed me: “American Born Confused Desi (ABCD).”On 9/11 one year, I wrote on Facebook that I would truly “never forget.” The media hijacks my narrative with wrongful Islamophobic messaging about my people. How could I ever have the audacity to call myself a term that does not even belong to me? America spans Canada, America spans Mexico. Sure, I am American, but I fail to be a patriot. Does being American mean I can travel to Israel with a hijab, brown skin, and a U.S. passport without being detained? Am I American then, too, or just racially Muslim?Muslims who dichotomize hijab—wear it or not—might not consider me as one of their own. How do I conduct community based participatory research if I am not accepted by my own people? Should I just abandon my hypothesis that living as American Muslim is theoretically a biracial or multiracial experience, which scientifically contributes to suicide risk? Who will believe me, and accept my story in science, in community, in media?

5.2. Analysis: Secondary Loss

5.3. On Socioeconomic Status and Suicide

6. On Identifying with Arabic-Speaking Bilingual Diasporas as Analyzed Through Collective Grief

6.1. Excerpt: Bi5 as Bilingual

Arabic script on an envelope of a letter I wrote to my advisor read: “In the Name of Allah, the Most Beneficent, the Most Merciful.” On the evening of October 7, 2023, joined by colleagues and my children, I was enjoying dinner at the home of my advisors. I passed by their kitchen, and saw a little cubby with ornaments and decorations, showcasing this letter I had written years ago. It was not long after that I received news of what happened overseas. God placed me there at that time, so divine. I passionately prayed for my colleagues, including Dr. Bahzad AlAkhras, a child psychiatrist native to Gaza, who I had met through the State Department just five months before.They say that the genocide began that day, yet I disagree. As a part of the greater Muslim diaspora, or Ummah as we say in Arabic, I knew this was just a resurgence of the violence and forced displacement that Palestinians have faced over the past century. Although I do not fluently speak in Arabic, I knew enough to get by in my travels to Arabic-speaking countries in West Asia and North Africa. I had no consoling words to share with my colleagues in Gaza, when, within a week, I found out that some of them and their families were murdered early in the first days of the war outbreak. What do I say, in Arabic, to my Gazan colleagues overseas, to convey what was in my heart? I did not have the words, not even in English.The Prophet Muhammad (peace and blessings upon him) stated: “None of you should wish for death because of a calamity befalling him; but if he must wish for death, he should say: ‘Oh Allah, keep me alive so long as life is better for me, and let me die if death is better for me.’” This is a saying, or hadith, I only found recently. Now, it is January 2025, and with the implementation of a ceasefire plan, my only prayer is that the lives of innocent Israelis and Palestinians alike are spared. Why is there no birthright for Palestinians? How can we reconnect with our roots?Before we prayed in the direction of the Kaaba, or house of God, in Mecca, Saudia Arabia, our Muslim ancestors prayed in the direction of the Al-Aqsa Mosque, also known as the Dome of the Rock. This is where the Prophet Muhammad miraculously ascended to the heavens and directly spoke to Allah on the holy night known as Israa wa Miraj. He met with Prophets Adam, Abraham, Moses, and Jesus. It was the night when our Islamic practice of the five daily prayers were sealed, as the Prophet spoke directly to Allah on ordaining them. When I prayed in Jerusalem at the Dome of the Rock in 2012, in the small cave underneath the prayer area, I felt connected to Allah and to the people of Jerusalem—the Hebrew speakers and Arabic speakers, alike.We share so many ancestors, yet conflict persists. Though geographically disconnected, every night I went to sleep and every morning I woke up, over the past 15 months, all that connected me to Gazans was an overwhelming survivors’ guilt. Every shower I took, every sip of water I drank, every jacket I wore, every bite of food I ate—all of it was a part of my daily mourning. If I could speak better Arabic, maybe I could process the pain better. But suffering has no language, and neither does sympathy. Our universal language is prayer.“In the Name of Allah, the Most Beneficent, the Most Merciful.”

6.2. Analysis: Collective Grief

6.3. On Genocide and Suicide

7. Discussion

7.1. Rigor of Methodology

7.2. Future Directions

8. Conclusions

“By having no illusions about the system, and by being ready to die, we begin to live.”—Huey P. Newton

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | “Spoons” is an informal term referencing the popular cultural concept of ‘spoon theory.’ It is a term commonly used by people with chronic illnesses or disabilities. The term refers to a daily quota of 10 spoons worth of energy, to be strategically divvied up by priority in terms of survivalism. |

References

- Abelson, Sara, Sarah Ketchen Lipson, Sasha Zhou, and Daniel Eisenberg. 2020. Muslim Young Adult Mental Health and the 2016 US Presidential Election. JAMA Pediatrics 174: 1112–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alakhras, Bahzad. 2024. War on Gaza: To Be a Palestinian Child Is a Curse, Not a Blessing|Middle East Eye. Available online: https://www.middleeasteye.net/opinion/war-gaza-palestinian-child-curse-not-blessing (accessed on 8 June 2024).

- Alvarez, Kiara, Lillian Polanco-Roman, Aaron Samuel Breslow, and Sherry Molock. 2022. Structural Racism and Suicide Prevention for Ethnoracially Minoritized Youth: A Conceptual Framework and Illustration Across Systems. The American Journal of Psychiatry 179: 422–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amri, Saara, and Fred Bemak. 2013. Mental Health Help-Seeking Behaviors of Muslim Immigrants in the United States: Overcoming Social Stigma and Cultural Mistrust. Journal of Muslim Mental Health 7: 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awaad, Rania, Osama El-Gabalawy, Ebony Jackson-Shaheed, Belal Zia, Hooman Keshavarzi, Dalia Mogahed, and Hamada Altalib. 2021. Suicide Attempts of Muslims Compared With Other Religious Groups in the US. JAMA Psychiatry 78: 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, Kendyl A., and Stephen M. Yoshimura. 2020. Death-Related Grief and Disenfranchised Identity: A Communication Approach. Review of Communication Research 8: 78–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beydoun, Khaled A. 2017. ‘Muslim bans’ and the (re)making of political islamophobia. University of Illinois Law Review 2017: 1733. Available online: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=lft&AN=125851958&site=ehost-live&scope=site (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- Black, Marc. 2007. Fanon and DuBoisian Double Consciousness. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/254693961 (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- Bostwick, J. Michael, Chaitanya Pabbati, Jennifer R. Geske, and Alastair J. McKean. 2016. Suicide Attempt as a Risk Factor for Completed Suicide: Even More Lethal Than We Knew. The American Journal of Psychiatry 173: 1094–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowleg, Lisa. 2012. The Problem with the Phrase Women and Minorities: Intersectionality-an Important Theoretical Framework for Public Health. American Journal of Public Health 102: 1267–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Browne, Annette J., Victoria L. Smye, and Colleen Varcoe. 2005. The Relevance of Postcolonial Theoretical Perspectives to Research in Aboriginal Health. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research Archive 37: 16–37. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Jacquelyn, Sabrina Matoff-Stepp, Martha L. Velez, Helen Hunter Cox, and Kathryn Laughon. 2021. Pregnancy-Associated Deaths from Homicide, Suicide, and Drug Overdose: Review of Research and the Intersection with Intimate Partner Violence. Journal of Women’s Health 30: 236–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carolyn Ellis | Communication Department | USF. n.d. Available online: https://www.usf.edu/arts-sciences/departments/communication/people/faculty/carolyn-ellis.aspx (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Cavanaugh, Courtenay E., Jill Theresa Messing, Melissa Del-Colle, Chris O’Sullivan, and Jacquelyn C. Campbell. 2011. Prevalence and Correlates of Suicidal Behavior among Adult Female Victims of Intimate Partner Violence. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior 41: 372–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesar Riani Costa, Luiza, and Jennifer White. 2024. Making Sense of Critical Suicide Studies: Metaphors, Tensions, and Futurities. Social Sciences 13: 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetin, Umit. 2016. Durkheim, Ethnography and Suicide: Researching Young Male Suicide in the Transnational London Alevi-Kurdish Community. Ethnography 17: 250–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Joe Kwun Nam, CoCo Ho Yi Tong, Corine Sau Man Wong, Eric Yu Hai Chen, and Wing Chung Chang. 2022. Life Expectancy and Years of Potential Life Lost in Bipolar Disorder: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry 221: 567–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandler, Amy. 2019. Boys Don’t Cry? Critical Phenomenology, Self-Harm and Suicide. The Sociological Review 67: 1350–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, Rodney, Norman B. Anderson, Vernessa R. Clark, and David R. Williams. 1999. Racism as a Stressor for African Americans: A Biopsychosocial Model. American Psychologist 54: 805–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corr, Charles A. 1998. Enhancing the Concept of Disenfranchised Grief. Omega 38: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, Kimberlé Williams. 2013. Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color. The Public Nature of Private Violence: Women and the Discovery of Abuse 43: 1241–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cwik, Mary, Novalene Goklish, Kristin Masten, Angelita Lee, Rosemarie Suttle, Melanie Alchesay, Victoria O’Keefe, and Allison Barlow. 2019. ‘Let Our Apache Heritage and Culture Live on Forever and Teach the Young Ones’: Development of The Elders’ Resilience Curriculum, an Upstream Suicide Prevention Approach for American Indian Youth. American Journal of Community Psychology 64: 137–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cwik, Mary F., Allison Barlow, Novalene Goklish, Francene Larzelere-Hinton, Lauren Tingey, Mariddie Craig, Ronnie Lupe, and John Walkup. 2014. Community-Based Surveillance and Case Management for Suicide Prevention: An American Indian Tribally Initiated System. American Journal of Public Health 104: e18–e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cwik, Mary F., Lauren Tingey, Alexandra Maschino, Novalene Goklish, Francene Larzelere-Hinton, John Walkup, and Allison Barlow. 2016. Decreases in Suicide Deaths and Attempts Linked to the White Mountain Apache Suicide Surveillance and Prevention System, 2001–2012. American Journal of Public Health 106: 2183–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwin Holmes, Andrew Gary. 2020. Researcher Positionality—A Consideration of Its Influence and Place in Qualitative Research—A New Researcher Guide. Shanlax International Journal of Education 8: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decker, Michele R., Holly C. Wilcox, Charvonne N. Holliday, and Daniel W. Webster. 2018. An Integrated Public Health Approach to Interpersonal Violence and Suicide Prevention and Response. Public Health Reports 133: 65S–79S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demographic Portrait of Muslim Americans. 2017. Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2017/07/26/demographic-portrait-of-muslim-americans/ (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- Diamond, Lisa M. 2020. Gender Fluidity and Nonbinary Gender Identities Among Children and Adolescents. Child Development Perspectives 14: 110–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doka, Kenneth J. 1999. Disenfranchised Grief. Bereavement Care 18: 37–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doka, Kenneth J. 2014. Disenfranchised Grief in Historical and Cultural Perspective. In Handbook of Bereavement Research and Practice: Advances in Theory and Intervention. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, pp. 223–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dome, Peter, Zoltan Rihmer, and Xenia Gonda. 2019. Suicide Risk in Bipolar Disorder: A Brief Review. Medicina 55: 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, Dustin T., and Mark L. Hatzenbuehler. 2014. Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Hate Crimes and Suicidality Among a Population-Based Sample of Sexual-Minority Adolescents in Boston. American Journal of Public Health 104: 272–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elder, Glen H. 1998. The Life Course as Developmental Theory. Child Development 69: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, Carolyn, Tony Adams, and Arthur Bochner. 2011. Autoethnography: An Overview on JSTOR. Historical Social Research 36: 273–90. [Google Scholar]

- Fanon, Frantz. 1961. The Wretched of the Earth. Translated by Richard Philcox. New York: Grove Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fasching-Varner, Kenneth J., Katrice A. Albert, Roland W. Mitchell, and Chaunda Allen, eds. 2014. Racial Battle Fatigue in Higher Education: Exposing the Myth of Post-Racial America. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, Chandra L., and Collins O. Airhihenbuwa. 2010. Critical Race Theory, Race Equity, and Public Health: Toward Antiracism Praxis. American Journal of Public Health 100: S30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forte, Alberto, Federico Trobia, Flavia Gualtieri, Dorian A. Lamis, Giuseppe Cardamone, Vincenzo Giallonardo, Andrea Fiorillo, Paolo Girardi, and Maurizio Pompili. 2018. Suicide Risk among Immigrants and Ethnic Minorities: A Literature Overview. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15: 1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galupo, M. Paz, Lex Pulice-Farrow, and Johanna L. Ramirez. 2017. ‘Like a Constantly Flowing River’: Gender Identity Flexibility among Nonbinary Transgender Individuals. In Identity Flexibility During Adulthood: Perspectives in Adult Development. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 163–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garner, Steve, and Saher Selod. 2015. The Racialization of Muslims: Empirical Studies of Islamophobia. Critical Sociology 41: 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, Gilbert C., Anna Hing, Selina Mohammed, Derrick C. Tabor, and David R. Williams. 2019. Racism and the Life Course: Taking Time Seriously. American Journal of Public Health 109: S43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geertz, Clifford. 1973. The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Geronimus, Arline T., Margaret Hicken, Danya Keene, and John Bound. 2006. ‘Weathering’ and Age Patterns of Allostatic Load Scores among Blacks and Whites in the United States. American Journal of Public Health 96: 826–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatzenbuehler, Mark L. 2011. The Social Environment and Suicide Attempts in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Youth. Pediatrics 127: 896–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatzenbuehler, Mark L. 2016. Structural Stigma and Health Inequalities: Research Evidence and Implications for Psychological Science. American Psychologist 71: 742–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzenbuehler, Mark L., Jo C. Phelan, and Bruce G. Link. 2013. Stigma as a Fundamental Cause of Population Health Inequalities. American Journal of Public Health 103: 813–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzenbuehler, Mark L., Katherine M. Keyes, and Deborah S. Hasin. 2009. State-Level Policies and Psychiatric Morbidity in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Populations. American Journal of Public Health 99: 2275–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, Maree, and Caroline Lenette. 2024. The Potential of Lived Experience-Led Knowledge to Dismantle the Academy. Disrupting the Academy with Lived Experience-Led Knowledge: Decolonising and Disrupting the Academy. Bristol: Policy Press. Available online: https://bristoluniversitypressdigital.com/edcollchap/book/9781447366362/ch009.xml (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Horrill, Tara C., Colleen Varcoe, Helen Brown, Kelli I. Stajduhar, and Annette J. Browne. 2024. Bringing an Equity Lens to Participant Observation in Critical Ethnographic Health Research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Christopher M., Melissa T. Merrick, and Debra E. Houry. 2020. Identifying and Preventing Adverse Childhood Experiences. JAMA 323: 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaniuka, Andrea R., and Jessamyn Bowling. 2021. Suicidal Self-Directed Violence among Gender Minority Individuals: A Systematic Review. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 51: 212–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasherwa, Amani, Caroline Lenette, Achol Arop, and Ajang Duot. 2024. ‘I Can’t Even Talk to My Parents About It’: South Sudanese Youth Advocates’ Perspectives on Suicide Through Reflexive Discussions and Collaborative Poetic Inquiry. Social Sciences 13: 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Køster, Allan, and Ester Holte Kofod, eds. 2023. Cultural, Existential and Phenomenological Dimensions of Grief Experience, 1st ed. London: Routledge. Available online: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=g_VPEAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PT205&dq=collective+grief&ots=FYn6nOAYqA&sig=q_6rGhOihe7O1NnY87NdBJM0Yz8#v=onepage&q=collective%20grief&f=false (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Kral, Michael J. 1998. Suicide and the Internalization of Culture: Three Questions. Transcultural Psychiatry 35: 221–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunst, Jonas R., Hajra Tajamal, David L. Sam, and Pål Ulleberg. 2012. Coping with Islamophobia: The Effects of Religious Stigma on Muslim Minorities’ Identity Formation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 36: 518–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuper, Laura E., Noah Adams, and Brian S. Mustanski. 2018. Exploring Cross-Sectional Predictors of Suicide Ideation, Attempt, and Risk in a Large Online Sample of Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Youth and Young Adults. LGBT Health 5: 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lassiter, Luke Eric. 2005. Collaborative Ethnography and Public Anthropology. Current Anthropology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press for the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research, vol. 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, Thomas Munk. 2011. Life Expectancy among Persons with Schizophrenia or Bipolar Affective Disorder. Schizophrenia Research 131: 101–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenette, Caroline. 2022. Participatory Action Research: Ethics and Decolonization. Participatory Action Research. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/book/41920 (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- Lenette, Caroline. 2023. Suicide Research with Refugee Communities: The Case for a Qualitative, Sociocultural, and Creative Approach. Social Sciences 12: 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenette, Caroline, and Jennifer Boddy. 2013. Visual Ethnography and Refugee Women: Nuanced Understandings of Lived Experiences. Qualitative Research Journal 13: 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenette, Caroline, Mark Brough, and Leonie Cox. 2013. Everyday Resilience: Narratives of Single Refugee Women with Children. Qualitative Social Work 12: 637–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenette, Caroline, Nelli Stavropoulou, Caitlin Nunn, Sui-Ting Kong, Tina Cook, Kate Coddington, and Sarah Banks. 2019. Brushed under the Carpet: Examining the Complexities of Participatory Research. Research for All 3: 161–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, Jeff, and Ellen L. Idler. 2018. Islamophobia and the Public Health Implications of Religious Hatred. American Journal of Public Health 108: 718–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, Sam. 2022. More than Half of US Trans Youth Considered Suicide in Past Year—Study. The Guardian. December 16. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2022/dec/16/us-trans-non-binary-youth-suicide-mental-health (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Lugo, Luis, and Alan Cooperman. 2011. The Future of the Global Muslim Population for 2010–2030. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center’s Forum on Religion & Public Life. [Google Scholar]

- Mapping the Global Muslim Population. 2009. Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewforum.org/2009/10/07/mapping-the-global-muslim-population/ (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- Markee, Numa. 2012. Emic and Etic in Qualitative Research. In The Encyclopedia of Applied Linguistics. Hoboken: Wiley, pp. 404–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKernan, Bethan. 2024. ‘Chronic Traumatic Stress Disorder’: The Palestinian Psychiatrist Challenging Western Definitions of Trauma. The Guardian. April 14. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/apr/14/mental-health-palestine-children (accessed on 8 June 2024).

- Menninger, Karl. 1938. Man Against Himself. Available online: https://archive.org/details/managainsthimsel00menn (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- Meyer, Ilan H. 1995. Minority Stress and Mental Health in Gay Men. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 36: 38–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Lisa R., and Eric Anthony Grollman. 2015. The Social Costs of Gender Nonconformity for Transgender Adults: Implications for Discrimination and Health. Sociological Forum 30: 809–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moran, Paul, Amy Chandler, Pat Dudgeon, Olivia J. Kirtley, Duleeka Knipe, Jane Pirkis, Mark Sinyor, Rosie Allister, Jeffrey Ansloos, Melanie A. Ball, and et al. 2024. The Lancet Commission on Self-Harm. The Lancet 404: 1445–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, Michael W., Kwok Leung, Daniel Ames, and Brian Lickel. 1999. Views from inside and Outside: Integrating Emic and Etic Insights about Culture and Justice Judgment. The Academy of Management Review 24: 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muslim Mental Health Conference. 2022. Grief Concepts Workshop Handout. Paper presented at the 2022 Muslim Mental Health Conference, New Haven, CT, USA, March 25–26. [Google Scholar]

- Newton, Huey P. 1973. Revolutionary Suicide. New York: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Ngunjiri, Faith Wambura, Kathy Ann C. Hernandez, and Heewon Chang. 2010. Living Autoethnography: Connecting Life and Research. Journal of Research Practice 6: E1. [Google Scholar]

- NIMH Director’s Innovation Speaker Series: Transformative Research Requires Insider Researchers. n.d. Available online: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/news/innovation-speaker-series (accessed on 16 November 2022).

- Noor-Oshiro, Amelia. 2021. American Muslims Are at High Risk of Suicide--20 Years Post-9/11, the Links Between Islamophobia and Suicide Remain Unexplored. Available online: https://theconversation.com/american-muslims-are-at-high-risk-of-suicide-20-years-post-9-11-the-links-between-islamophobia-and-suicide-remain-unexplored-167034 (accessed on 1 February 2024).

- Norwood, Kristen. 2013. Grieving Gender: Trans-Identities, Transition, and Ambiguous Loss. Communication Monographs 80: 24–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onah, Michael E. 2018. The Patient-to-Prisoner Pipeline: The IMD Exclusion’s Adverse Impact on Mass Incarceration in United States. American Journal of Law and Medicine 44: 119–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Brumer, Amaya, Mark L. Hatzenbuehler, Catherine E. Oldenburg, and Walter Bockting. 2015. Individual- and Structural-Level Risk Factors for Suicide Attempts Among Transgender Adults. Behavioral Medicine 41: 164–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pew Research. 2013. Second-Generation Americans A Portrait of the Adult Children of Immigrants. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2013/02/07/second-generation-americans/ (accessed on 13 March 2019).

- Pihkala, Panu. 2024. Ecological Sorrow: Types of Grief and Loss in Ecological Grief. Sustainability 16: 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polanco-Roman, Lillian, and Regina Miranda. 2013. Culturally Related Stress, Hopelessness, and Vulnerability to Depressive Symptoms and Suicidal Ideation in Emerging Adulthood. Behavior Therapy 44: 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radford, Jynnah. n.d. Key Findings About U.S. Immigrants|Pew Research Center. Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/06/17/key-findings-about-u-s-immigrants/ (accessed on 27 July 2019).

- Rafei, Leila. 2021. How the FBI Spied on Orange County Muslims And Attempted to Get Away with It. ACLU News. Available online: https://www.aclu.org/news/national-security/how-the-fbi-spied-on-orange-county-muslims-and-attempted-to-get-away-with-it (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- Ribeiro, Jessica D., and Thomas E. Joiner. 2009. The Interpersonal-Psychological Theory of Suicidal Behavior: Current Status and Future Directions. Journal of Clinical Psychology 65: 1291–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, Jessica D., Xieyining Huang, Kathryn R. Fox, and Joseph C. Franklin. 2018. Depression and Hopelessness as Risk Factors for Suicide Ideation, Attempts and Death: Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal Studies. British Journal of Psychiatry 212: 279–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouhani, Farhang. 2017. Religion, Identity and Activism: Queer Muslim Diasporic Identities. In Geographies of Sexualities: Theory, Practices and Politics. London: Routledge, pp. 169–79. Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781315254470-25/religion-identity-activism-queer-muslim-diasporic-identities-farhang-rouhani (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Said, Edward. 1978. Orientalism. New York: Pantheon Books. [Google Scholar]

- Said, Edward. 2016. Orientalism. Social Theory Re-Wired. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samari, Goleen. 2016. Islamophobia and Public Health in the United States. American Journal of Public Health 106: 1920–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samari, Goleen, Héctor E. Alcalá, and Mienah Zulfacar Sharif. 2018. Islamophobia, Health, and Public Health: A Systematic Literature Review. American Journal of Public Health 108: e1–e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sather, Marnie. 2024. Researcher as Insider: Bringing Together Narrative Therapy Practices and Feminist Lived Experience Methodologies in the Context of Suicide Research. Qualitative Report 29: 112–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott-Pollock, Julie-Ann, Frank P. Trimble, and Evan Scott-Pollock. 2022. Managing the Able-Bodied Gaze: The Complicated, Risky Decision to Perform Disabled Identity in Autoethnographic Performance. Liminalities: A Journal of Performance Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Shahwar, Deeba. 2014. Portrayal of the Muslim World in the Western Print Media Post-9/11: Editorial Treatment in ‘The New York Times’ and ‘The Daily Telegraph’. Pakistan Horizon 67: 133–66. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/44988714?seq=1 (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Singer, Merrill. 2000. A Dose of Drugs, a Touch of Violence, a Case of AIDS: Conceptualizing the Sava Syndemic. Free Inquiry in Creative Sociology 28: 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Sjoblom, Erynne, Winta Ghidei, Marya Leslie, Ashton James, Reagan Bartel, Sandra Campbell, and Stephanie Montesanti. 2022. Centering Indigenous Knowledge in Suicide Prevention: A Critical Scoping Review. BMC Public Health 22: 2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotero, Michelle. 2006. A Conceptual Model of Historical Trauma: Implications for Public Health Practice and Research. Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice 1: 93–108. [Google Scholar]

- Standley, Corbin J. 2022. Expanding Our Paradigms: Intersectional and Socioecological Approaches to Suicide Prevention. Death Studies 46: 224–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staples, James. 2015. Personhood, Agency and Suicide in a Neo—Liberalizing South India. In Suicide and Agency: Anthropological Perspectives on Self-Destruction, Personhood, and Power. London: Routledge, pp. 27–45. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/30339952.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Staples, James, and Tom Widger. 2012. Situating Suicide as an Anthropological Problem: Ethnographic Approaches to Understanding Self-Harm and Self-Inflicted Death. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry 36: 183–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subica, Andrew M., and Li Tzy Wu. 2018. Substance Use and Suicide in Pacific Islander, American Indian, and Multiracial Youth. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 54: 795–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweet, Paige L. 2019. The Sociology of Gaslighting. American Sociological Review 84: 851–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Peter, Patricia Gooding, and Alex Mathew Wood. 2011. The Role of Defeat and Entrapment in Depression, Anxiety, and Suicide. Psychological Bulletin 137: 391–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thambinathan, Vivetha, and Elizabeth Anne Kinsella. 2021. Decolonizing Methodologies in Qualitative Research: Creating Spaces for Transformative Praxis. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Trevor Project. 2022. The Trevor Project Releases New State-Level Data on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health, Victimization, & Access to Support. The Trevor Project Blog. December 15. Available online: https://www.thetrevorproject.org/blog/the-trevor-project-releases-new-state-level-data-on-lgbtq-youth-mental-health-victimization-access-to-support/ (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Thomas, Nigel Mark. 2006. What’s Missing from the Weathering Hypothesis? American Journal of Public Health 96: 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toomey, Russell B., Amy K. Syvertsen, and Maura Shramko. 2018. Transgender Adolescent Suicide Behavior. Pediatrics 142: e20174218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Orden, Kimberly A., Tracy K. Witte, Kelly C. Cukrowicz, Scott R. Braithwaite, Edward A. Selby, and Thomas E. Joiner, Jr. 2010. The Interpersonal Theory of Suicide. Psychological Review 117: 575–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vélez-Agosto, Nicole M., José G. Soto-Crespo, Mónica Vizcarrondo-Oppenheimer, Stephanie Vega-Molina, and Cynthia García Coll. 2017. Bronfenbrenner’s Bioecological Theory Revision: Moving Culture from the Macro into the Micro. Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science 12: 900–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayakumar, Lakshmi, and Gregory Armstrong. 2019. Surveillance for Self-Harm: An Urgent Need in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries. The Lancet Psychiatry 6: 633–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virupaksha, H. G., Daliboyina Muralidhar, and Jayashree Ramakrishna. 2016. Suicide and Suicidal Behavior among Transgender Persons. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine 38: 505–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahlig, Jeni L. 2015. Losing the Child They Thought They Had: Therapeutic Suggestions for an Ambiguous Loss Perspective with Parents of a Transgender Child. Journal of GLBT Family Studies 11: 305–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson-Gegeo, Karen Ann. 1988. Ethnography in ESL: Defining the Essentials. TESOL Quarterly 22: 575–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, Jennifer, Ian Marsh, Michael J. Kral, and Jonathan Morris. 2015. Critical Suicidology Transforming Suicide Research and Prevention for the 21st Century. Available online: https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/distributed/C/bo69966645.html (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Yip, Andrew K. T., and Amna Khalid. 2012. Looking for Allah: Spiritual Quests of Queer Muslims. Queer Spiritual Spaces: Sexuality and Sacred Places, 81–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwisler, Joshua James. 2021. Linguistic Genocide or Linguicide? Apples—Journal of Applied Language Studies 15: 103419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

noor, a.e. Bi5: An Autoethnographic Analysis of a Lived Experience Suicide Attempt Survivor Through Grief Concepts and ‘Participant’ Positionality in Community Research. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 405. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14070405

noor ae. Bi5: An Autoethnographic Analysis of a Lived Experience Suicide Attempt Survivor Through Grief Concepts and ‘Participant’ Positionality in Community Research. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(7):405. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14070405

Chicago/Turabian Stylenoor, amelia elias. 2025. "Bi5: An Autoethnographic Analysis of a Lived Experience Suicide Attempt Survivor Through Grief Concepts and ‘Participant’ Positionality in Community Research" Social Sciences 14, no. 7: 405. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14070405

APA Stylenoor, a. e. (2025). Bi5: An Autoethnographic Analysis of a Lived Experience Suicide Attempt Survivor Through Grief Concepts and ‘Participant’ Positionality in Community Research. Social Sciences, 14(7), 405. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14070405