I have always loved the expression ‘Call for Papers’ and its elegant acronym CfP. When I imagine a Special Issue, I think of a CfP as “an appeal to search for wisdom, understanding, insight and knowledge”, and hope that authors hear the call as “a gift…to which they must respond” (de Beer 2009, p. 21). In 2023, I shared a CfP for this Special Issue on ‘Critical Suicide Studies: Decolonial and Participatory Creative Approaches’ with much excitement and trepidation, wondering who will answer the call? The outcome is an outstanding collection of eleven publications: four essays, four empirical papers, two provocations, and a narrative review. In an academic environment where it is increasingly difficult to find time to engage with new and fascinating ideas, editing this Special Issue has been a real privilege.

The articles (summarised below) are abundant with insights that will shift and expand knowledge on how we understand, research, and address suicide. The discipline of critical suicide studies is a dynamic research area, enriched with creative and justice-oriented methodologies. The works of both leaders and new voices in this field are brought together in this Special Issue to create and sustain novel pathways for suicide scholarship. Together, we unsettle the entrenched faithfulness to biomedical and positivist approaches, which have a disproportionate focus on individual risk factors and psychiatric interventions. The articles respond to Chua’s (2014, p. 4) call for a shift in the way we examine suicide, “not only or even primarily as empirical fact—one to be confirmed or debunked on the strength of numbers—but also notably as a social and moral reality that inflects political, social, and familial life”. As a global network of critical suicidologists, we analyse, interpret, and argue for perspectives that are usually relegated to the margins, leading the way in advocating for the oft-neglected sociocultural, political, structural, and environmental dimensions, and the growing need for anti-colonial methodologies to reframe discourses on suicide.

An important commitment from the outset of editing this Special Issue was to prioritise First Nations scholarship and majority world authors, to align with an anti-colonial research approach (see Lenette 2025). By doing so, this Issue has become a forum for contributions that directly seek to counter epistemic injustice (Anderson 2012; Fricker 2007), which is an enduring problem in suicidology and many other disciplines. Despite the critical ‘turn’ in suicide studies, we are yet to address the ongoing imbalances in scholarship, still dominated by white, North American, and Eurocentric perspectives (see Ansloos & White, this issue; Lenette 2023). That is not to say that this Special Issue resolves such problems, as all authors live and work in Canada, Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States (or CAUKUS). Even when a CfP such as this reaches authors and suicide researchers who live and work in majority world countries, a range of factors preclude them from contributing new perspectives to global conversations on suicide. The importance of finding better ways to amplify majority world scholarship in critical suicide studies cannot be overstated.

Authors featured in this Special Issue are a mix of well-established scholars who pioneered the critical suicide studies movement and researchers who have recently completed their PhD candidatures. In some instances, this Special Issue became a mentoring opportunity, where senior academics supported early career scholars to frame their work for publication. No two articles are the same, and each takes us on a unique and contextual exploration of suicidality through different approaches. When combined, these critical perspectives offer rich and complementary learnings that advance the discipline. This is the kind of scholarship I wish I could engage with more often—the key messages caused me to stop, reflect, think, reconsider. This Special Issue is the continuation of critical conversations that need to progress much further to produce tangible changes in suicide research, policy, and intervention.

One of the main obstacles when creating this Issue was finding reviewers who would understand and support the scholarship under consideration with constructive feedback. As the very aim was to challenge positivist approaches and language, it was not entirely surprising that some reviewer comments were unfavourable. I applaud the authors’ commitment to challenging those reductive perceptions of what suicide scholarship (and academic publications more broadly) should look like. This is an ongoing concern that reinforces epistemic injustice and dominant western-centric understandings of knowledge—and who holds knowledge (Lenette 2025). There is certainly more work to be done in that respect. I encourage readers who are able to create publication opportunities for First Nations and majority world authors to further disrupt these normative dissemination and publication frameworks.

- Articles in this Special Issue

1. First Nations scholar Jeffrey Ansloos and Jennifer White (Canada) expand the contours of critical suicide studies with a call to radically reimagine the discipline as a critical, relational practice rooted in solidarity and transformative possibilities. Their paper provides a map for moving from critique to justice-oriented action as an integral rather than peripheral concern of suicide research. By presenting witnessing, dreaming, and prefiguration as key methodologies, the authors set the course for the way forward in critical suicide studies.

2. Jude Smit, Erminia Colucci, and Lisa Marzano (United Kingdom) document the impact of arts-based and visual methods in their research on the experiences of higher education students who have attempted suicide. Participants’ evocative artworks conveyed a unique way to communicate what is hard to put into words: mortality, constraint and freedom, fear and hope, isolation, masking, reflections on one’s place in the universe, and what is seen/unseen and voiced/unvoiced.

3. Muruwari Gumbaynggirr researcher Phillip Orcher with Victoria Palmer and Aboriginal scholar Tyson Yunkaporta (Australia) outline the Bigaagarri protocol, which enfolds Aboriginal health and wellbeing perspectives and values, and the physicality of personal location in place and social context. Using lived experience narratives, the authors share how Bigaagarri can help reimagine suicidality by embedding Indigenous knowledge within interventions and disrupt the ongoing recolonisation of Indigenous identities.

4. Antonia Alvarez (United States) describes how performance methodologies were used to discuss views on suicide among cisgender; heterosexual; and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and māhū (LGBTQM) Kānaka Maoli (Native Hawaiians). The themes of risks, rites, and resistance were embedded in their experiences of colonisation and suicidality. These findings point to the importance of relationships, cultural understandings of identity and identification, and healing through cultural practices.

5. Luiza Cesar Riani Costa and Jennifer White (Brazil/Canada) offer important insights into how critical suicide studies scholars, practitioners, and people with lived experience of suicide conceptualise and make sense of this discipline. Their analysis of metaphors in participants’ responses points to the complexities and contradictions that cannot be conveyed via the dominant language on suicidality, thus challenging the myth of a single, unquestionable truth.

6. amelia elias noor (United States) shares a sociocultural account of suicide through their lived experiences of Islamophobia, identifying as a genderfluid non-binary woman, being socially biracial, holding a postpartum bipolar diagnosis, and being connected to a diaspora. Their autoethnographic exploration of grief based on intersecting identities aims to support marginalised scholars with lived experience of suicide.

7. Lydia Gitau (Australia) reflects on the importance of silences to express feelings about suicidality, especially when working with people for whom English is not a first language. Drawing on research experiences in the context of forced migration, the paper describes how expressive arts activities provide alternative ways to destabilise the control, domination, and exploitation that over-relying on words can perpetuate.

8. Adrian Flores (United States) shares a philosophical analysis of their ‘suicide note’ through the lens of modernity, colonisation, and enslavement. By doing so, the essay highlights how suicide is a culmination of historical and cultural forces rather than purely an individual crisis.

9. Amani Kasherwa, myself, Achol Arop, and Ajang Duot (Australia) discuss the lack of dialogue and the absence of community-based support structures to address suicide in the South Sudanese community. We used reflexive discussions and collaborative poetry to amplify South Sudanese perspectives and counter the absence of refugee-specific contributions in critical suicide studies.

10. marcela polanco and Anthony Pham (United States) apply a decolonial lens from Abya Yala, el Caribe, and Eastern Europe to disrupt the coloniality of senses, time, and being in suicide scholarship. By annotating a crisis suicide call, they challenge the erasure and violent imposition of a singular way of understanding suicide.

11. Joanna Brooke, myself, and Indigenous colleagues Marianne Wobcke and Marly Wells (Australia) provide a brief analysis of academic and grey literature on Indigenous community-driven models that aim to address suicidality. Our review highlights the key characteristics of models that work when they centre Indigenous leadership and culturally grounded research praxis.

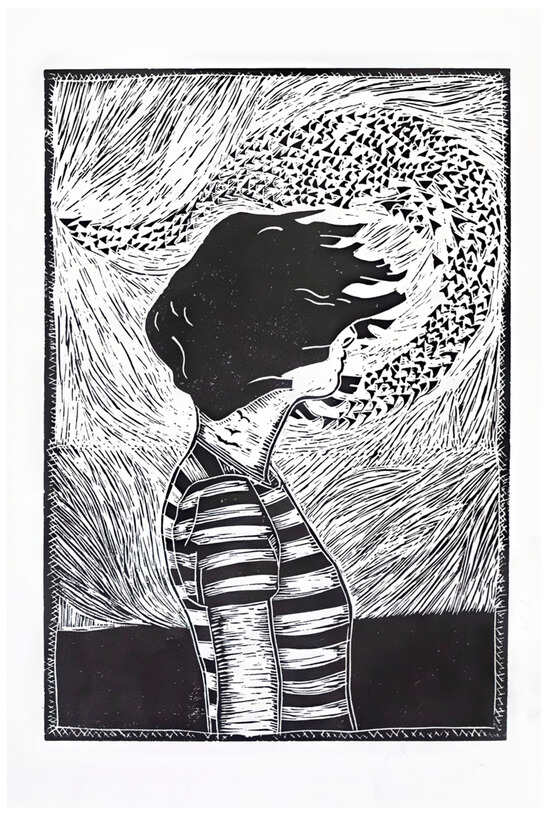

A note about the artwork used in the cover design (Figure 1 below): Murmuring is a monochrome linocut print created for this Issue by Melissa Telford, an artist living and creating on Dja Dja Wurrung land. The limited colour palette explores contrasting views and the spaces and experiences that sit somewhere in between. The partially obscured face and the (in)visibility of the wind convey what is seen and unseen, while the movement of birds speaks to the ever-changing emotional landscape that traverses a line between turmoil and healing. Although sometimes hesitant to call herself an artist, art has remained a constant in Melissa’s life to explore, understand, heal and connect. As an art therapist, she is drawn to the power of art to create space beyond the limitations of words. As an introvert, she connects with the power of art to amplify a quiet or overlooked voice, a small detail, or a meaning that may not be fully formed or understood.

Figure 1.

Murmuring (2025). Permission: Melissa Telford.

I thank the journal Social Sciences for their dedication to rapidly publishing new work that needs to be shared. This makes a significant difference to the track records of early career academics especially, and in a broader sense, challenges preconceived notions about publishing norms in the social sciences.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Anderson, Elizabeth. 2012. Epistemic Justice as a Virtue of Social Institutions. Social Epistemology 26: 163–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, Jocelyn Lim. 2014. In Pursuit of the Good Life: Aspiration and Suicide in Globalizing South India. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- de Beer, Fanie. 2009. Philosophy is Calling. Phronimon 10: 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Fricker, Miranda. 2007. Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lenette, Caroline. 2023. Suicide Research with Refugee Communities: The Case for a Qualitative, Sociocultural, and Creative Approach. Social Sciences 12: 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenette, Caroline, ed. 2025. Anti-Colonial Research Praxis: Methods for Knowledge Justice. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).