1. Introduction

Cyberbullying entails purposeful and repeated harmful actions conducted through digital communication channels, such as social media, text messages, or online platforms (

Baldry et al. 2015;

Pozzoli and Gini 2020). It poses a growing threat to the well-being and safety of individuals, especially youths. Conversely, cybervictimization refers to being targeted and harmed by cyberbullying behaviors (

Baldry et al. 2015;

Pozzoli and Gini 2020). As digital platforms become increasingly embedded in daily life, the potential for online aggression and victimization has expanded, prompting urgent calls to understand and address the factors contributing to these behaviors. Among the known predictors of cyberbullying and cybervictimization, family dynamics, such as parental psychological control, play a pivotal role.

Parental psychological control involves the utilization of manipulative and intrusive strategies by parents to influence their child’s thoughts, emotions, and actions (

Scharf and Goldner 2018). These methods encompass techniques like guilt-inducing, shaming, dismissing emotions, and imposing restrictions on the child’s independence. When youths experience heightened degrees of parental psychological control, it can lead to adverse psychological consequences, including heightened anxiety and depression (

Rogers et al. 2020). Some studies propose that youths subjected to heightened levels of parental psychological control may be more susceptible to engaging in cyberbullying or experiencing cybervictimization (

Kokkinos et al. 2016;

Lin et al. 2020). In relation to cyberbullying, research suggests that adolescents exposed to controlling parental practices may internalize these behaviors and, in turn, replicate them in their peer interactions (

Verrastro et al. 2024a,

2024b). The online environment may offer them a space to assert power or vent feelings of frustration and helplessness. Consequently, these youths might perceive the internet as an avenue to exert power and dominance over others, similar to their experiences of being controlled in their personal lives (

Baldry et al. 2019;

Padır et al. 2020). Engaging in cyberbullying may offer them a sense of empowerment and a way to vent their feelings of frustration, anger, or powerlessness anonymously in the online realm.

Regarding cybervictimization, the emotional vulnerabilities instilled by psychological control, such as low self-esteem, poor emotional regulation, and dependence on external validation, may render adolescents more susceptible to being targeted by online aggressors (

Lozano-Blasco et al. 2024). In fact, youths who have experienced parental psychological control may be more prone to becoming targets of cyberbullying themselves (

Lin et al. 2020;

Padır et al. 2020). The emotional distress induced by controlling parenting practices can leave them open to manipulation and online attacks from cyberbullies. The cycle of experiencing psychological control and then becoming a cybervictim may perpetuate the child’s emotional distress and sense of powerlessness (

Baldry et al. 2019;

Kokkinos et al. 2016). Furthermore, youths raised in an environment of psychological control might encounter challenges in forming healthy and assertive interpersonal relationships. This could result from their lack of experience in making independent decisions, expressing their emotions, or advocating for themselves due to the restrictive nature of their upbringing (

Kokkinos et al. 2016;

Lin et al. 2020). As a consequence, they may struggle to set boundaries and respond effectively to cyberbullying situations, thus becoming easier targets for online harassment and victimization.

In addition to parenting, maladaptive personality traits, such as those within the Dark Triad, have emerged as significant predictors of cyberbullying and cybervictimization. The Dark Triad, encompassing narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy, represents three socially aversive personality traits. Individuals with heightened levels of narcissism exhibit an inflated sense of self-importance, constantly seeking admiration and lacking empathy toward other individuals (

Schimmenti et al. 2019;

Vize et al. 2020). They may exploit others to achieve personal goals and be highly sensitive to perceived criticism or rejection. Those high in Machiavellianism display manipulative and strategic tendencies, willing to exploit other people for personal advantage (

Jonason and Webster 2010;

Vize et al. 2020). They often engage in deception and manipulation to achieve their objectives, showing little concern for the well-being of their targets. Meanwhile, individuals with elevated psychopathy levels demonstrate a lack of empathy, remorse, and conscience (

Jonason and Webster 2010;

Schimmenti et al. 2019). Their tendencies towards impulsivity and antisocial behaviors disregard the feelings and rights of others.

Research indicates that certain parenting practices, such as psychological control, may contribute to the development of personality traits associated with the Dark Triad. For example, parental psychological control, characterized by manipulation, invalidation of emotions, and an emphasis on the child’s compliance with parental expectations, can lead to the development of narcissistic traits (

Jonason et al. 2014;

Li et al. 2020). When youths are raised in an environment where their self-worth hinges on meeting their parents’ demands, they may develop an inflated sense of self-importance and entitlement. Similarly, parental psychological control might inadvertently nurture Machiavellian traits in youths (

Jonason et al. 2014;

Liu et al. 2021). If youths observe that manipulation and strategic behaviors are effective means of achieving goals or avoiding punishment, they may adopt similar tactics in their own interactions with others. While it is thought that psychopathy arises from a blend of genetic and environmental influences, some studies suggest that harsh and controlling parenting practices could be connected with an elevated risk of psychopathic traits in youths (

Li et al. 2020;

Liu et al. 2021). Such parenting approaches may disrupt the development of empathy and conscience in a child, thereby contributing to the development of psychopathic tendencies (

Calaresi et al. 2024b).

Research findings suggest that individuals with elevated Dark Triad traits display a higher likelihood of engaging in cyberbullying and cybervictimization. The Dark Triad encompasses personality traits characterized by manipulative, exploitative, and callous tendencies, which can find a fitting avenue for expression in the digital realm (

Goodboy and Martin 2015;

Hajlo et al. 2015). The correlation of the Dark Triad with cyberbullying can thus be influenced significantly by the relative anonymity and detachment that online platforms provide. With the shield of anonymity, cyberbullies can act without immediate consequences or accountability for their actions (

Hajlo et al. 2015;

Panatik et al. 2022). For those high in Dark Triad traits, this anonymity can become particularly enticing, as it can remove the fear of facing social backlash or retaliation that might otherwise curb their harmful behaviors in face-to-face interactions (

Calaresi et al. 2024b). The manipulative and exploitative inclinations of individuals with Dark Triad traits may thus play a critical role in cyberbullying incidents (

Panatik et al. 2022;

Schade et al. 2021). They possess a keen ability to identify vulnerabilities in their targets and exploit them to cause emotional harm. Personal information shared online, such as insecurities or weaknesses, can become a weapon for these cyberbullies to effectively humiliate and torment their victims (

Goodboy and Martin 2015;

Schade et al. 2021). Furthermore, individuals exhibiting elevated Dark Triad levels often lack empathy and remorse, which can further fuel their engagement in cyberbullying. Individuals high in Dark Triad traits exhibit diminished empathic responses, enabling them to dismiss the emotional impact of their cyberbullying behavior on their victims (

Hajlo et al. 2015;

Schade et al. 2021). The absence of guilt or remorse means they are less likely to experience moral dilemmas or regret regarding their harmful actions, leading them to persist in their cyberbullying behaviors without remorse (

Goodboy and Martin 2015;

Panatik et al. 2022).

Additionally, those with Dark Triad traits may also be involved in cybervictimization, either as targets of retaliation or due to the interpersonal conflicts their behaviors provoke. Their antagonistic and provocative interpersonal style can increase the likelihood of negative interactions online, leading to peer rejection or targeted attacks (

Azami and Taremian 2021;

Gajda et al. 2023). In some cases, individuals high in Dark Triad traits may perceive themselves as victims when their manipulations are exposed or challenged, thereby contributing to a subjective sense of victimization. Moreover, their low empathy and poor emotion regulation can hinder effective coping with online hostility, making them more vulnerable to emotional distress when they become targets themselves (

Azami and Taremian 2021;

Gajda et al. 2023). The absence of guilt or remorse further complicates this cycle, as such individuals may neither recognize the harm they cause nor learn from being harmed, sustaining maladaptive interaction patterns in digital environments.

The present study focuses on parental psychological control, Dark Triad personality traits, and cyberbullying/cybervictimization to better understand the interplay of family, personality, and online behavior in adolescence. These variables are considered together based on theoretical and empirical evidence suggesting that negative parenting practices can shape the development of maladaptive personality traits, which in turn may increase the likelihood of involvement in online aggression, either as perpetrators or victims. Parental psychological control, in particular, has been linked to emotional dysregulation and antisocial tendencies, which may foster traits such as Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy. These traits are especially relevant in digital contexts, where the reduced accountability of online interactions may encourage manipulative and harmful behavior. Furthermore, by examining both cyberbullying and cybervictimization, this study acknowledges that adolescents with high Dark Triad traits may not only engage in online aggression but also provoke or become entangled in hostile exchanges. Bringing these variables together in a unified model allows for a more integrated understanding of the mechanisms through which family dynamics and personality traits shape adolescents’ online experiences and can inform targeted prevention and intervention efforts.

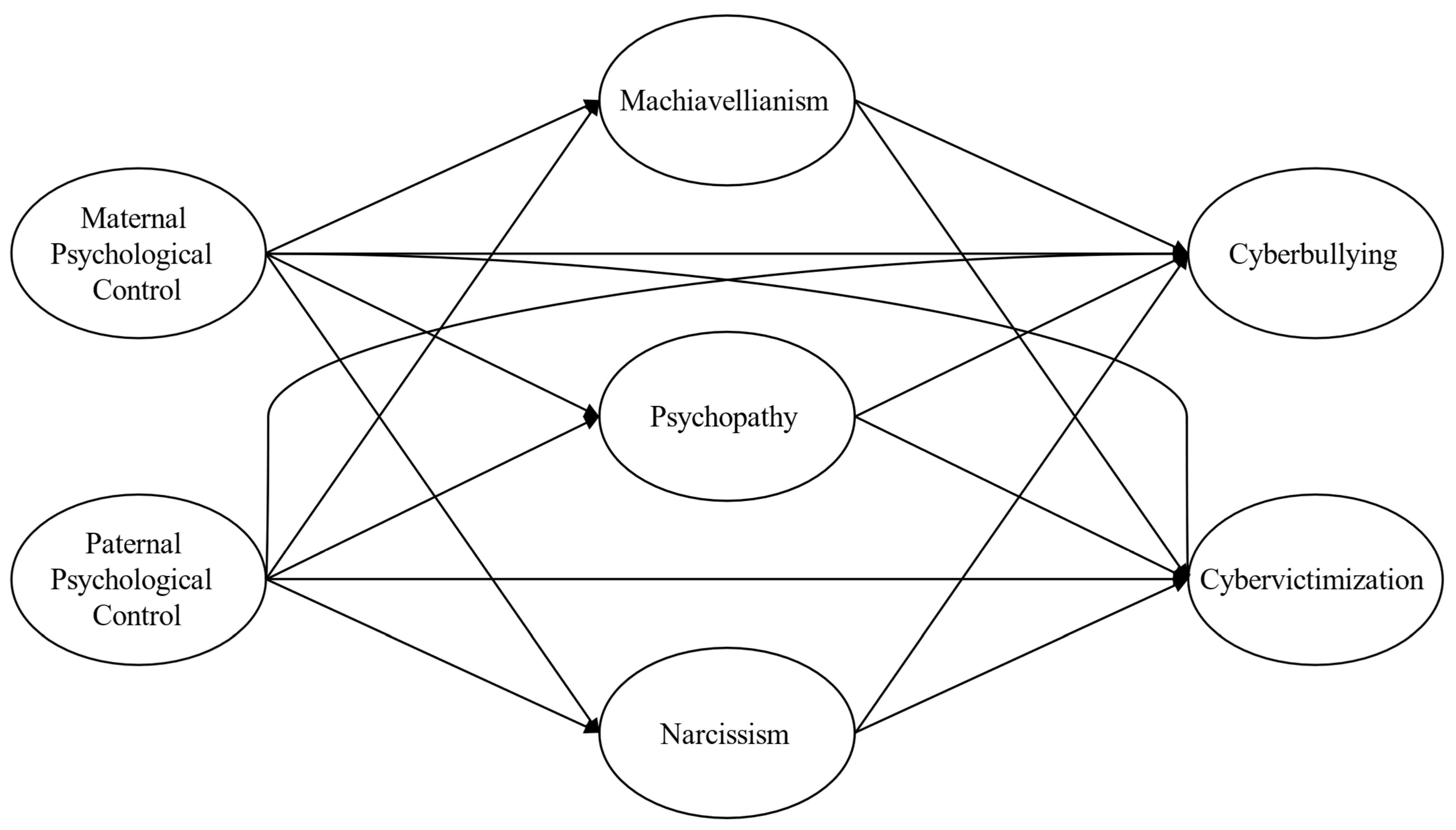

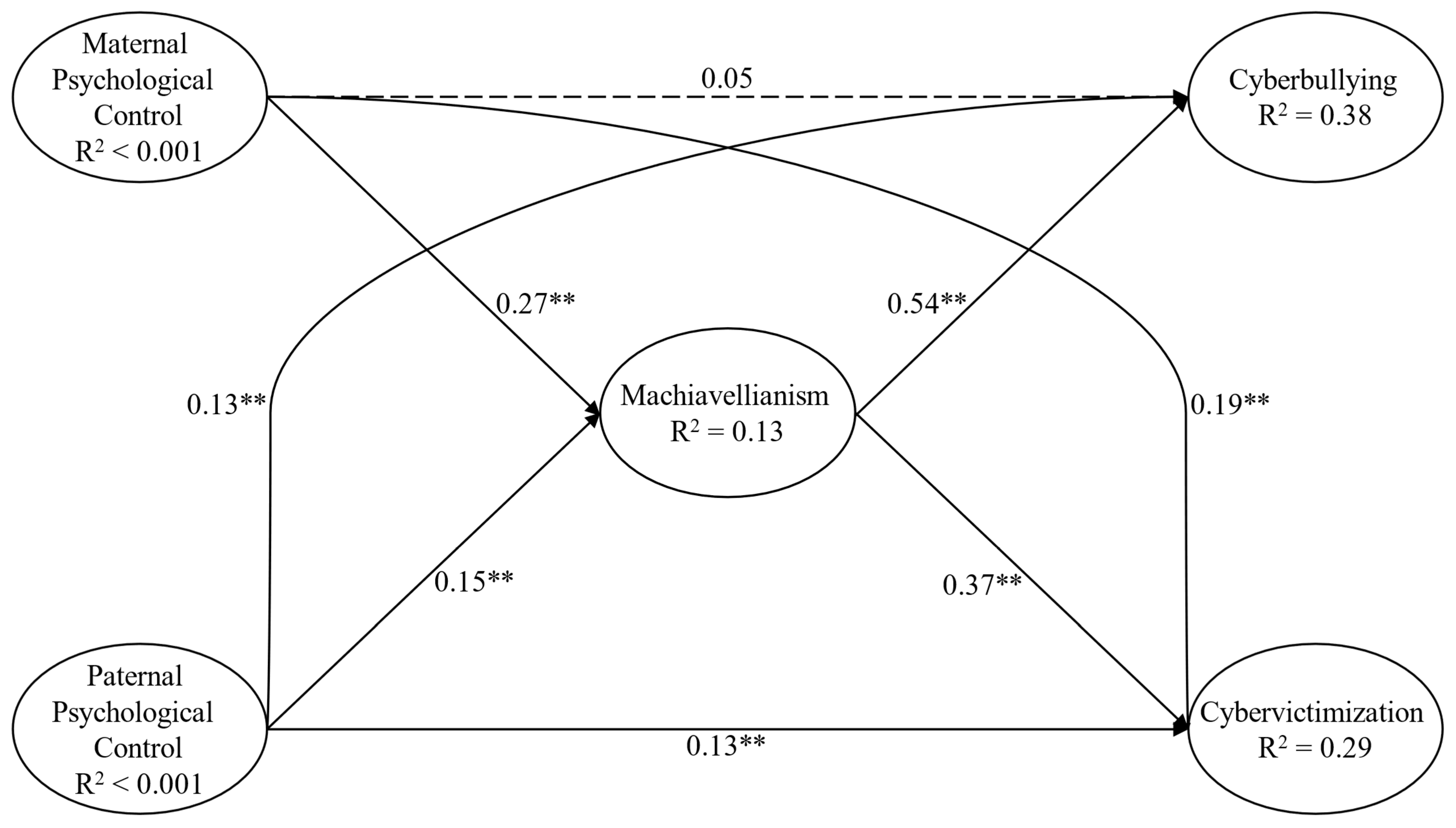

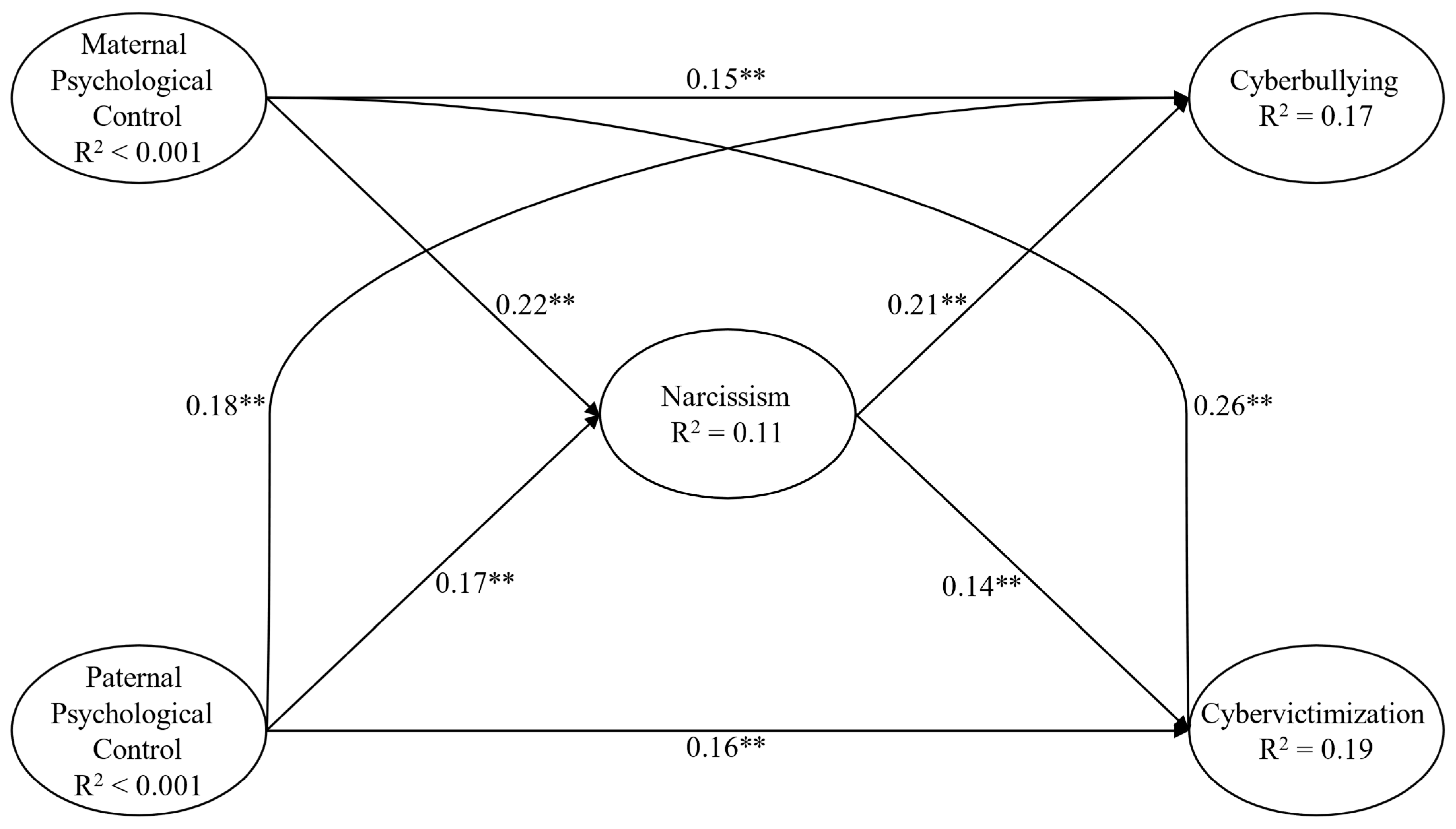

The primary objective of the present research is to examine whether the Dark Triad traits, Machiavellianism, psychopathy, and narcissism, mediate the relationships between maternal and paternal psychological control and adolescents’ involvement in cyberbullying and cybervictimization (see

Figure 1). Specifically, based on the existing literature, we hypothesize that higher levels of parental psychological control will be positively associated with higher levels of Dark Triad traits in adolescents (H1) and that each of these traits will, in turn, predict increased engagement in cyberbullying (H2) and a higher likelihood of experiencing cybervictimization (H3). A further hypothesis (H4) is that the Dark Triad traits will mediate the links between both maternal and paternal psychological control and cyberbullying/cybervictimization behaviors. Moreover, the study will explore, through multiple models, the unique contributions of maternal versus paternal psychological control and of each individual Dark Triad trait to provide a more nuanced understanding of their roles in adolescents’ online behaviors. This approach aims to clarify the underlying mechanisms through which family dynamics and maladaptive personality traits interact to influence both perpetration and victimization in digital contexts.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

A sample of 1016 young people in Italy, equally divided between 508 women and 508 men, made up the study. The age range of participants was 18–25 years old (M = 21.64, SD = 2.22), meaning they generally had at least 13 years of schooling, corresponding roughly to the period following completion of upper secondary education or end of high school. All participants in the current study were living with their parents at the time of data collection. This condition was ensured during recruitment to maintain consistency in assessing perceived maternal and paternal psychological control. A convenience sampling method was used, and participants were recruited online through various widely used social media platforms, including Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp. The survey link was shared in public groups, community pages, and through personal networks. To increase reach, participants were encouraged to share the link with others, allowing for broader dissemination through a snowball sampling effect. In terms of educational achievement, 57% of participants completed high school, 31% university, 11% postgraduation, and 11% middle school. Thirty percent of participants were students, thirteen percent were jobless, forty-four percent were working, and thirteen percent worked for themselves. In the sample, 46% were not in a relationship, 41% were engaged, 6% were cohabiting, and 7% were married. The research complied with the standards set out by the Italian Association of Psychology (AIP) and the Helsinki Declaration. The Institute for the Study of Psychotherapies, Specialization School in Brief Psychotherapies with a Strategic Approach (ISP; number: ISP-IRB-2023-5) IRB approved the study. Participants were fully informed about their rights before participation, including the voluntary nature of the study and their ability to withdraw at any time without any issue. Contact information for support resources was provided in the debriefing materials to assist participants who might have experienced distress due to the sensitive nature of the topic. The survey was conducted anonymously to protect participants’ privacy. No incentives were offered, and the survey remained open for one month to facilitate broad recruitment.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Parental Psychological Control

These variables were examined using the Italian form of the Psychological Control Scale (PCS) (

Barber 1996;

Costa et al. 2015). The sample was requested to determine the degree of psychological control they bore from their mothers and fathers separately. This was performed by responding to a set of eight items, such as “My mother/father changes the subject whenever I have something to say”. Each item was evaluated using a 3-point Likert scale, spanning from 1 (not like her/him) to 3 (a lot like her/him). To calculate the comprehensive extent of parental psychological control, The average of the scores for the eight items was computed, with elevated scores reflecting heightened perceived psychological control. The original Italian validation of the PCS demonstrated good internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranging from 0.78 to 0.81 (

Costa et al. 2015). In this study, the internal consistency of the scale was found to be good, as indicated in

Table 1.

2.2.2. Dark Triad

The Italian validation of the Dark Triad Dirty Dozen scale (DTDD) (

Jonason and Webster 2010;

Schimmenti et al. 2019) was carried out to evaluate such traits. The DTDD measurement scale comprises 12 items, 4 for each dark triad trait (narcissism, psychopathy, Machiavellianism). An item assessing narcissism is “I tend to want others to admire me”. Items assessing psychopathy comprise statements like “I tend to lack remorse”. An item measuring Machiavellianism is “I tend to manipulate others to get my way”. A greater presence of the associated personality characteristic is indicated by higher scores on each subscale. The initial Italian validation of the DTDD reported satisfactory internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha values reaching 0.82 for the global scale (

Schimmenti et al. 2019). As seen in

Table 1, the DTDD scale’s internal consistency was found to be good in this study.

2.2.3. Cyberbullying and Cybervictimization

To measure cyberbullying and cybervictimization, the study utilized the Italian version of the cyberbullying subscale and cybervictimization subscale of the behaviors in cyberbullying scale (

Pozzoli and Gini 2020). The cyberbullying subscale, consisting of four items, assessed behaviors related to cyberbullying, such as “I threatened or insulted someone using the Internet or the phone”. The cybervictimization subscale, also comprising four items, measured experiences of being a victim of cyberbullying, for example, “Someone created an online group in which people made fun of me”. Participants were instructed to answer on a Likert scale, going from 1 to 5 (never to almost always). Greater values on both subscales indicated greater cyberbullying and cybervictimization, respectively. The original Italian validation of the subscales indicated acceptable internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranging from 0.75 to 0.77 (

Pozzoli and Gini 2020). In the present research, Cronbach’s values were found to be good (

Table 1).

2.3. Statistical Analyses

To perform correlation analysis and descriptive statistics, IBM SPSS 27 software was used. The following statistical operations were carried out in the primary analysis using RStudio’s Lavaan package.

A MANOVA was conducted to examine the effect of sex on multiple dependent variables, which included maternal psychological control, paternal psychological control, Machiavellianism, psychopathy, narcissism, cyberbullying, and cybervictimization. Sex was treated as the independent variable, and the rest of the variables were treated as dependent variables. When a significant multivariate effect of sex was found, follow-up univariate analyses were performed, with Bonferroni correction applied to control for multiple comparisons.

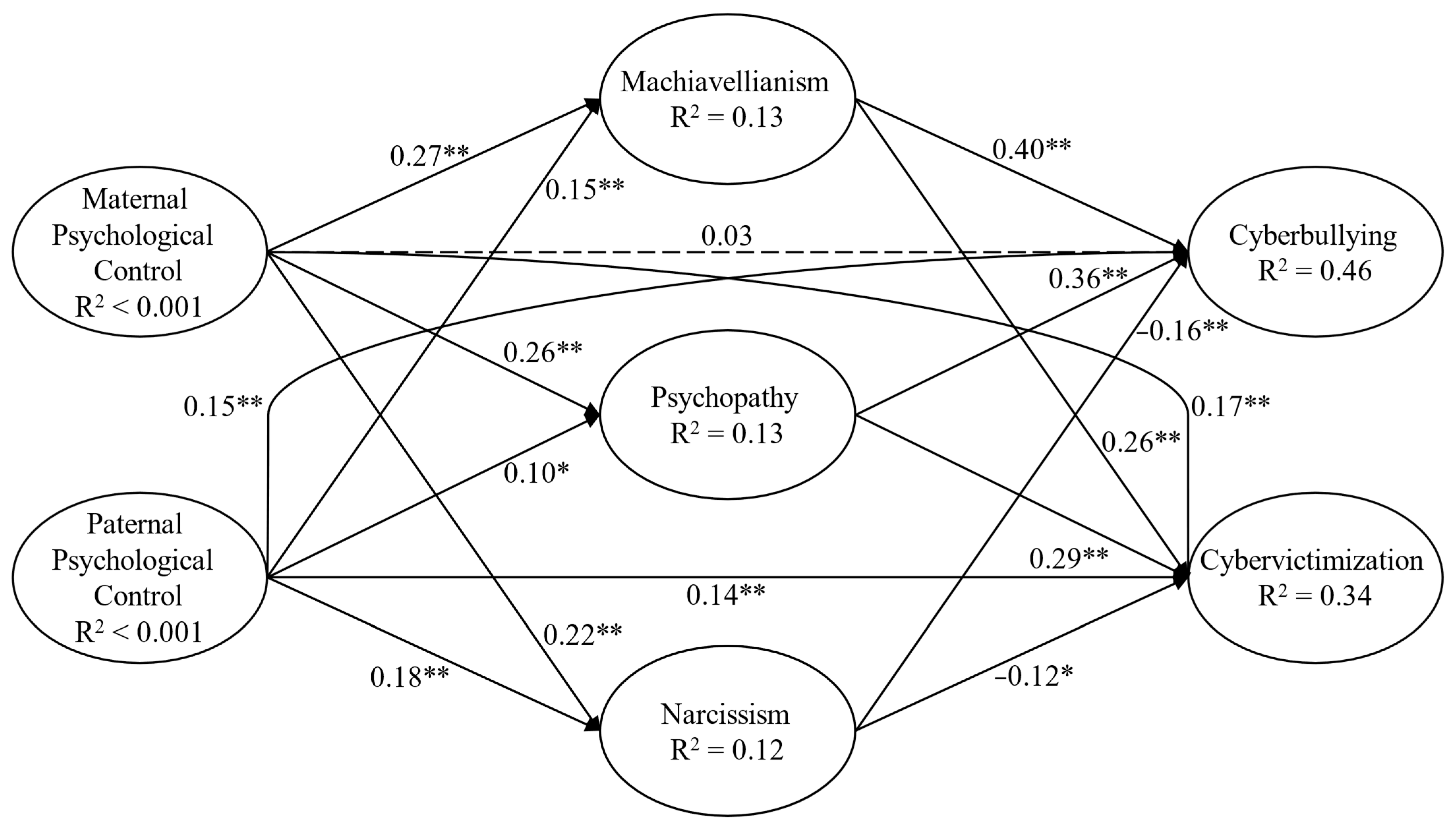

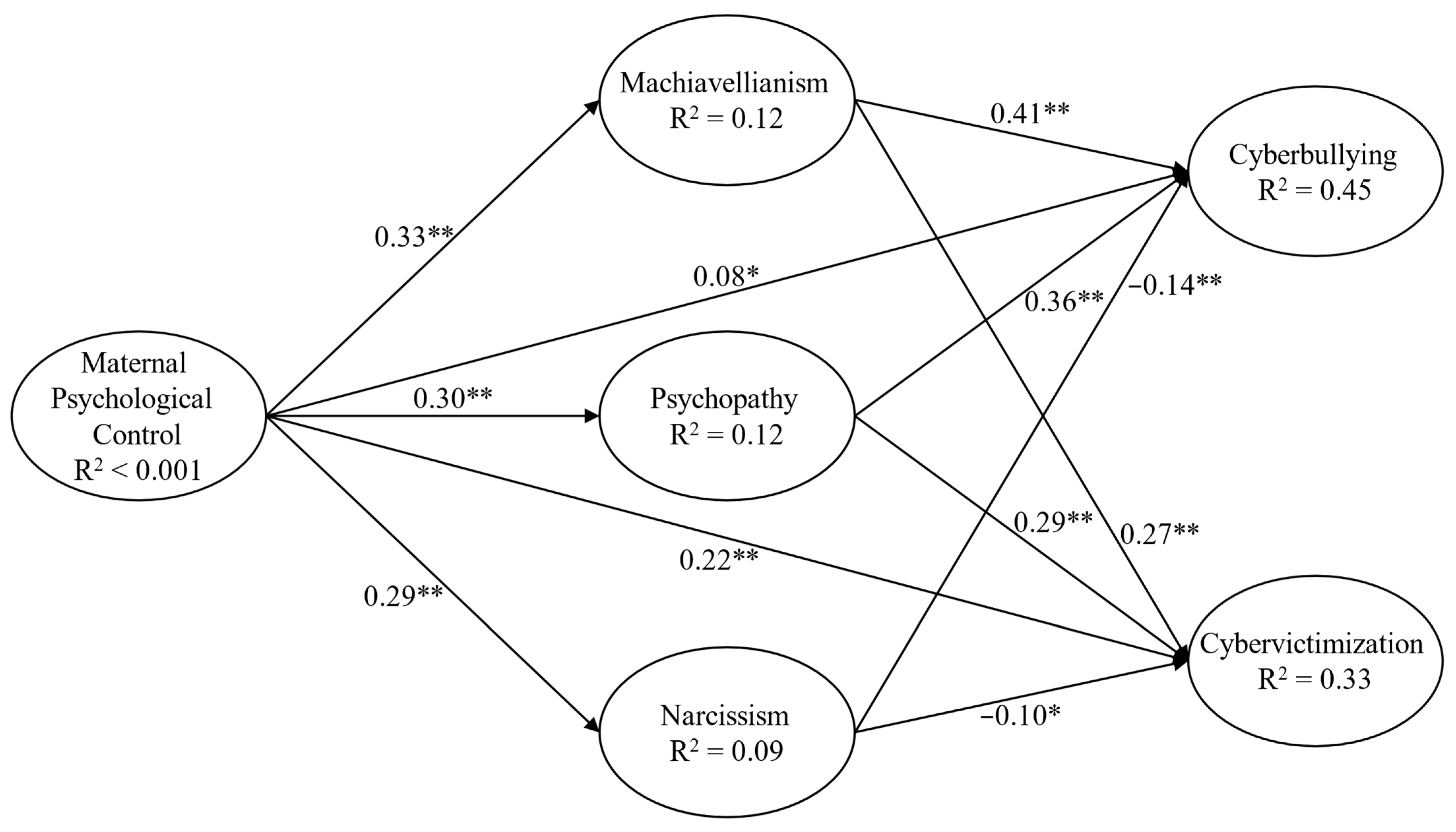

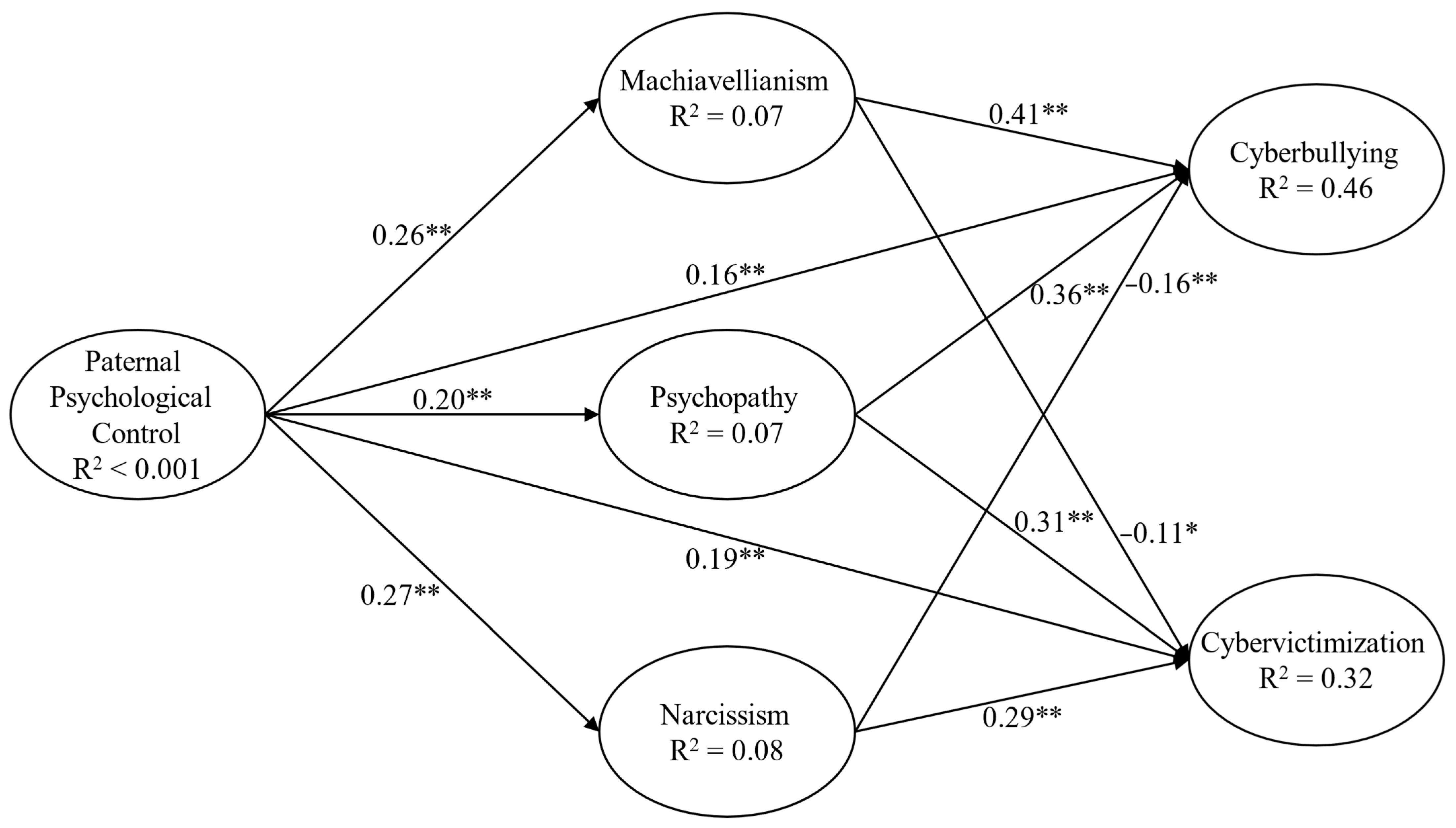

To assess the hypothesized paths, the Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) technique was applied. The first model had maternal and paternal psychological control as predictor variables, dark triad traits as mediator variables, and cyberbullying and cybervictimization as outcome variables. The second model included maternal psychological control as the only predictor, the dark triad traits as mediator variables, and cyberbullying and cybervictimization as outcome variables. The third model included paternal psychological control as the only predictor, Machiavellianism, psychopathy, and narcissism as mediator variables, and cyberbullying and cybervictimization as outcome variables. The second and third models investigated the independent role of maternal and paternal psychological control, respectively. The fourth model included maternal and paternal psychological control as predictor variables, Machiavellianism as the only mediator variable, and cyberbullying and cybervictimization as outcome variables. The fifth model included maternal and paternal psychological control as predictor variables, psychopathy as a mediator, and cyberbullying and cybervictimization as outcome variables. The sixth one considered maternal and paternal psychological control as predictor variables, narcissism as the only mediator variable, and cyberbullying and cybervictimization as outcome variables. The fourth, fifth and sixth models investigated the independent role of Machiavellianism, psychopathy, and narcissism, respectively. The bias-corrected confidence interval approach was used to assess the importance of indirect routes in the mediation models. In order to estimate confidence intervals and ascertain statistical significance, this was produced using bootstrap resampling using 5000 resamples.

4. Discussion

The main aim of the research was to assess the influencing effect of Machiavellianism, psychopathy, and narcissism in the pathways connecting maternal and paternal psychological control with cyberbullying and cybervictimization. The results of the research offer significant considerations into the complex links among these variables, shedding light on the complex dynamics involving parental psychological control, the dark triad, and behaviors related to cyberbullying. Our study findings support previous research emphasizing the significant impact of parental influences and personality traits on influencing youth behavior (

Saladino et al. 2024b). Specifically, we observed a significant connection between parental psychological control and cyberbullying behaviors, indicating that emerging adults who experienced heightened degrees of parental psychological control had a higher likelihood of participating in cyberbullying. This aligns with existing studies highlighting the negative outcomes associated with overly controlling parenting practices on the social and psychological development of children (

Costa et al. 2015;

Lin et al. 2020). Furthermore, our study unveiled a noteworthy influencing role of negative traits on the link between parental psychological control and cyberbullying behaviors. This suggests that the dark traits act as a process by which parental psychological control influences cyberbullying behaviors among emerging adults. Our findings corroborate previous research that has separately analyzed the association linking the dark triad and cyberbullying (

Panatik et al. 2022) and the connection of parental psychological control with cyberbullying (

Padır et al. 2020). However, our study contributes by providing evidence for the mediating effect of the dark traits in that link. Moreover, our study also uncovered complex relationships of the variables under investigation, indicating that the link between parental psychological control, the dark triad, and cyberbullying behaviors is multifaceted and requires further exploration.

4.1. The Unique Impact of Maternal and Paternal Psychological Control

The observed non-significant direct relationship linking maternal psychological control with cyberbullying, as highlighted in the combined mediation model where both maternal and paternal psychological control are included as predictors, indicates a complex interplay between parental psychological control, dark personality traits, and cyberbullying behaviors. Some theoretical explanations can provide insight into these findings. One possible explanation is that the cumulative impact of maternal and paternal psychological control interacts to influence cyberbullying behaviors. It is conceivable that parental psychological control from both figures has a cumulative effect on emerging adults, amplifying their engagement in cyberbullying behaviors. This combined influence may overshadow the specific impact of maternal psychological control when examined in isolation. In other words, the presence of paternal psychological control might contribute to additional variability in cyberbullying behaviors that was previously attributed solely to maternal psychological control. Furthermore, it is worth considering that maternal and paternal psychological control might result in different impacts on the involvement of young adults in cyberbullying activities. Previous research has suggested that the style and methods of psychological control can differ between mothers and fathers (

Yang et al. 2022;

Yu et al. 2021). Therefore, it is plausible that the effect of maternal psychological control on cyberbullying behaviors can be stronger or more pronounced when examined independently. However, when both maternal and paternal control is simultaneously considered, the unique impact of maternal control may become less discernible, as paternal psychological control could overshadow its influence.

In contrast to cyberbullying, cybervictimization reflects the experience of being targeted by harmful online behaviors, which may be influenced differently by parental psychological control. The present findings suggest that both maternal and paternal psychological control can contribute to an increased risk of cybervictimization, potentially by fostering environments where young adults feel less supported or more controlled, which may reduce their resilience against online victimization (

Lozano-Blasco et al. 2024). Unlike the mechanisms that drive engagement in cyberbullying, the pathways to becoming a victim may be more closely related to vulnerability factors such as lowered self-esteem, diminished coping resources, or impaired social skills, which can be exacerbated by controlling parenting styles (

Lozano-Blasco et al. 2024). Moreover, the differential impact of maternal versus paternal psychological control on cybervictimization remains an important area for further investigation, as distinct parenting behaviors may uniquely affect how young adults navigate social risks online. Recognizing these differences is critical for tailoring prevention and support strategies that address the specific needs of cybervictims as separate from those of perpetrators.

4.2. The Mediation Effects of the Dark Triad

In all the examined models, significant positive mediation effects of Machiavellianism and psychopathy were observed for the indirect paths. These mediation effects can be explained through various theoretical perspectives. One such perspective is Social Learning Theory, which suggests that individuals learn behaviors through observation, imitation, and reinforcement (

Navarro and Marcum 2019;

Shadmanfaat et al. 2020). In the framework of our research, young adults who encounter elevated degrees of parental psychological control may observe and internalize the manipulative behaviors associated with Machiavellianism, as well as the lack of empathy and remorse associated with psychopathy. These emerging adults may perceive these traits as effective strategies for gaining power and control in their social interactions. Consequently, they have a higher tendency to participate in cyberbullying activities, which involve the use of manipulation and a disregard for the feelings of others. Furthermore, both Machiavellianism and psychopathy are characterized by a general antagonism (

Schimmenti et al. 2019;

Vize et al. 2020). Young adults who encounter elevated degrees of parental psychological control may internalize these traits (

Li et al. 2020;

Vize et al. 2020), which may manifest in cyberbullying behaviors (

Panatik et al. 2022;

Schade et al. 2021). In cyberbullying, individuals intentionally harm others online without considering the consequences or the impact on their victims. This aligns with the power-seeking, controlling, and manipulative tendencies associated with Machiavellianism, as well as the lack of remorse and disregard for others’ well-being linked to psychopathy. Additionally, it is important to consider that Machiavellianism is associated with a desire for power, control, and manipulation, while psychopathy is linked to a lack of remorse and a disregard for the rights and well-being of others (

Schimmenti et al. 2019;

Vize et al. 2020). Parental control, characterized by intrusive and overbearing parenting practices, may create a power imbalance within the relationship between parents and their children (

Costa et al. 2015;

Whittington and Turner 2023). Youth who experience such power imbalances may develop Machiavellian and psychopathic tendencies to restore a sense of power and control in how they engage with other individuals (

Panatik et al. 2022;

Schade et al. 2021), including engaging in cyberbullying behaviors. Lastly, it is worth considering that parental psychological control, characterized by excessive domination and interference in the lives of emerging adults, may inadvertently reinforce negative behaviors associated with Machiavellianism and psychopathy (

Jonason et al. 2014;

Li et al. 2020). Youth who engage in manipulative and remorseless behaviors may receive reinforcement or validation from their parents when these behaviors align with the parental control style. This reinforcement has the potential to enhance the connection between parental psychological control and the emergence of Machiavellian and psychopathic traits, ultimately leading to increased engagement in cyberbullying behaviors.

Notably, although the mediating effect of the dark triad traits was stronger for cyberbullying, these traits also showed significant associations with cybervictimization. This finding aligns with the existing literature, which emphasizes the interconnection between cyberbullying and cybervictimization as two closely related aspects of online aggression and harassment (

Azami and Taremian 2021;

Gajda et al. 2023). While it is not always the case, there are instances where individuals who engage in cyberbullying also experience cybervictimization, creating a cyclic pattern of aggression and victimization. This can occur when the same person who perpetrates bullying behaviors becomes a target of retaliation or aggression from others. The reciprocal nature of online interactions can lead to individuals playing the roles of both aggressors and victims at different times (

Ademiluyi et al. 2022;

Baldry et al. 2019;

Pozzoli and Gini 2020). Additionally, certain individuals may be more susceptible to both perpetrating and experiencing cyberbullying due to underlying vulnerability factors. As an illustration, people with diminished self-esteem, social difficulties, or prior experiences of victimization could exhibit a greater tendency to engage in aggressive behaviors as a coping mechanism or to gain a sense of control (

Azami and Taremian 2021;

Gajda et al. 2023). However, these same vulnerability factors can also increase their likelihood of becoming targets of cyberbullying themselves (

Ademiluyi et al. 2022;

Baldry et al. 2019;

Pozzoli and Gini 2020). This highlights the complex interplay between aggression and victimization in the online environment. It is important to highlight that while the dark personality traits showed significant mediation effects concerning cybervictimization, the effect sizes were smaller compared to their effects on cyberbullying. This suggests that other factors beyond dark personality traits can have a more significant impact on individuals’ experiences of being victimized online. These factors could include contextual influences, such as peer dynamics or features of the online context, in addition to personal vulnerabilities that contribute to the likelihood of becoming a target of cyberbullying.

4.3. The Specific Role of Narcissism

The discrepancy between the positive correlation observed between narcissism and cyberbullying/cybervictimization in Pearson’s correlation analysis and the negative relationship observed in the mediation model, where narcissism acts as a negative mediator while Machiavellianism and psychopathy act as positive mediators, can be explained by several theoretical considerations. One potential explanation is the presence of a third variable (in this case, both Machiavellianism and psychopathy), which can suppress or alter the relationship between two variables (

Pandey and Elliott 2010). It is possible that the stronger links between Machiavellianism and psychopathy with cyberbullying are higher than the connection between narcissism and cyberbullying when simultaneously present in the mediation paths. In such a scenario, the presence of the remaining two dark personality traits suppresses the Direct Path of narcissism on cyberbullying, resulting in a negative relationship when mediated by narcissism. The stronger associations of Machiavellianism and psychopathy with engaging in cyberbullying behaviors compared to narcissism may overshadow the influence of narcissism when the collective presence of the three dark triad traits is taken into account, leading to the observed negative relationship in the mediation model. In addition, each trait can have different impacts on the connection between parental psychological control and engagement in cyberbullying activities. In the first model, which considers only narcissism, narcissism shows a significant impact, suggesting that when considered alone, narcissism enhances the path linking parental psychological control with cyberbullying behaviors. However, in the more complex model that includes Machiavellianism, psychopathy, and narcissism, narcissism acts as a negative influencing variable, lowering the link between parental psychological control and cyberbullying behaviors. The results indicate that the mediation effect of narcissism may fluctuate based on whether other dark triad traits are present or absent. The complex interplay among Machiavellianism, psychopathy, and narcissism results in different mediation effects for narcissism in the two models. This highlights the importance of keeping in mind the collective influence of dark personalities if examining their influencing impact on the association of parental psychological control with cyberbullying behaviors. These results are in line with other studies showing that although narcissism appears to have a link with cyberbullying episodes, its mediating effects become non-significant or negative if considering the other traits (

Fanti et al. 2012;

Fernández-del-Río et al. 2021). Nonetheless, it is important to consider the result concerning the negative impact of narcissism with cautiousness, considering that the beta value was small, similar to the latter study (

Fernández-del-Río et al. 2021). The relevant literature highlights complex paths, with different outcomes highlighted based on the type of narcissism (

Fan et al. 2019;

Zerach 2016). Although this research helps to comprehend such intricate relationships, additional studies are needed to develop a wider knowledge and comprehension of these phenomena.

4.4. Limitations

The research presents some limits. Firstly, the use of a cross-sectional methodology employed in this research prevents our capacity to confirm temporal connections among the study variables. To acquire a more thorough comprehension of the observed findings over time, it could be valuable to carry out longitudinal studies that track individuals’ experiences and behaviors over an extended period. By incorporating longitudinal designs, we can obtain more robust evidence regarding the associations observed in our research. Secondly, it is important to recognize the exclusive use of self-reports, which may introduce bias. To mitigate such bias, research could include different types of measures to obtain a more comprehensive assessment of the variables under investigation. By using diverse data sources, we can enhance the validity and reliability of the results. Thirdly, it is worth noting that our study solely relied on online data collection, potentially constraining the applicability of our results. To address this limitation and ensure a more diverse and representative sample, future research could employ different data collection methods, including in-person interviews or data obtained from offline sources. By adopting a more comprehensive approach to data collection, we can obtain a better understanding of the phenomenon across a wider range of populations and contexts. Lastly, although our analyses employed robust parametric methods and bootstrap techniques, the data showed some deviations from normality. Although it is important to note that normality tests are extremely sensitive to large sample sizes, we acknowledge this as a potential limitation and suggest that future research, including replication studies with different samples and analytic strategies, could further investigate and confirm the robustness of our study findings.

4.5. Future Research Suggestions

To advance the credibility and breadth of our knowledge, future studies should seek to duplicate and build upon our results by investigating varied populations and considering various factors. This can involve investigating individuals from different age groups, cultural backgrounds, and clinical populations. By conducting studies with a broader range of participants, we can determine the generalizability of the observed relationships and develop a wider comprehension of the impact of psychological control from parents and the dark triad traits on individuals’ engagement in cyberbullying behaviors. Moreover, the clinical implications derived from our study emphasize the importance of developing targeted interventions to address cyberbullying. Future research should focus on designing and evaluating interventions that effectively target the identified risk factors, including parental psychological control and dark personality traits. Assessing the effectiveness of interventions in reducing cyberbullying behaviors, improving parent-child relationships, and fostering positive social skills would provide valuable evidence for the creation of evidence-based programs. Given the complex nature of cyberbullying, it is crucial for future research to adopt a multidisciplinary approach. Integrating perspectives from psychology, sociology, education, and technology can offer a deeper understanding of such behavior. Collaborative efforts across disciplines would enable researchers to explore the multifaceted nature of cyberbullying, considering factors such as peer influences, school environments, and technological platforms in conjunction with individual and familial factors.