Abstract

This study explores the effects of husbands’ post-infidelity behaviors on wives’ forgiveness from a gender perspective. The study employs a longitudinal research design and hermeneutic phenomenology to investigate the wives’ forgiveness potential paths/experiences after their husband’s infidelity. It involves 15 years of in-depth interviews with five wives who had encountered their husbands’ infidelity, with three to six interviews per participant. The findings reveal that husbands’ post-infidelity behaviors are associated with power dynamics in the marriage. At the same time, pressures from culture, gender roles, and social expectations lead wives to adopt “pseudo-forgiveness.” The study proposes two pathways to “genuine forgiveness” for wives. The path includes phases of “Her Rethinking,” leading to the “Balance Marital Relationship and Non-Self-Sacrifice stage.” For low-power-in-relationship wives, the path comprises stages such as “Her Awakening,” “Challenge Women’s Roles in Social Expectations,” and “Take Actions to Enhance Her Power/Ability,” ending in “Balance Marital Roles and Self-Realization.” Both pathways emphasize that forgiveness is a personal decision-making process and that empowerment and enhanced wives’ ability are essential for achieving “genuine forgiveness.” These findings can contribute to marriage and family work and welfare services, helping wives and professionals understand the types and processes of forgiveness and better navigate complex challenges related to marital infidelity.

1. Introduction

Although marriage is no longer considered the only life choice in modern society, most people still choose to enter marriage. Regardless of their social or economic status, couples from diverse backgrounds generally hope for a lasting marriage that satisfies their needs (Karney and Bradbury 2020). A 15-year longitudinal study found that married individuals typically report higher levels of happiness than unmarried ones, highlighting the significant impact of marriage on personal well-being (Rothwell 2024). However, if many persons engage in marriage as a path towards greater happiness, then infidelity—violating marital vows—becomes a significant threat to that happiness. Marriage symbolizes exclusive romantic commitment and a clear promise of sexual fidelity, and is widely recognized as a global standard (Regan 2015). As cases of infidelity increase, the happiness and stability in marriage are often compromised, significantly raising the risk of marital breakdown.

In recent years, Taiwan’s divorce rate has ranked among the highest in Asia. From 2001 to 2023, Taiwan’s crude divorce rate remained between 2 and 2.75 per 1000 people, meaning that 1 in every 2 to 3 married couples divorced (Monthly Bulletin of Interior Statistics 2024). Infidelity has long been a primary reason for divorce in Taiwan (Wu et al. 2012).

As early as 1989, Betzig’s study of 186 global societies found that infidelity was the most common cause of divorce, surpassing marital discord, financial issues, or family disputes (Betzig 1989). Treas and Giesen (2000) also noted that due to high expectations for sexual fidelity in American marriages, infidelity frequently serves as a direct cause of marital breakdown. Although Taiwan’s divorce rate is relatively high compared to other Asian countries, large-scale studies on the prevalence of infidelity in Taiwan remain scarce. According to the world’s largest extramarital dating site, “Ashley Madison,” Taiwan saw a surge in memberships in 2020, making it the country with the highest registration rate in Asia. Among these members, 84% viewed extramarital affairs as a form of self-healing (Zhu 2021). This phenomenon reflects the complex social attitudes in Taiwan towards marital infidelity, and warrants further investigation.

Taiwan’s society displays significant gender differences in its approach to marriage and infidelity, which have evolved over time. In the 1950s and 1960s, discussions on infidelity often contained implicit gender double standards. Starting in the 1980s, with the rise of social awareness and legal knowledge, divorce and legal avenues became crucial tools for women to safeguard their rights in the face of marital breakdowns (Y.-T. Chen 2016). Although the Civil Code established monogamy, bigamy was not deemed invalid, and de facto bigamy continued to exist, particularly among wealthy men who could maintain multiple families. It was not until the 1985 amendment that bigamy was formally declared invalid. Despite clear legal stipulations, social tolerance for male infidelity remains higher, and women often face asymmetric punishment (C.-J. Chen 2013). Gender double standards are still evident in Taiwan (Hwong et al. 2012). Over the past few decades, Taiwan has progressed towards gender equality through women’s movements, UN gender equality initiatives, and local legislative reforms, gradually changing social expectations of women’s roles in marriage. Nonetheless, traditional gender roles and cultural norms continue to influence Taiwanese women’s psychological responses and behavioral choices when faced with their husbands’ infidelity.

In this context, this study aims to explore how husbands’ behaviors after infidelity affect wives’ forgiveness, with several critical focal points. First, this research mainly focuses on the gender perspective. As Norlock (2018) pointed out, gender is central to forgiveness; discussions that do not center on gender and women’s experiences tend to create a universal concept of forgiveness, which often misses the opportunity to capture the complexity and multiple meanings of forgiveness. Additionally, culture is a consideration, as forgiveness varies significantly across cultures (Dillow and Denes 2022), making forgiveness research within the Chinese cultural context highly valuable academically. Furthermore, emphasizing the value of “women’s lived experiences,” feminist studies remind us of the significance of centering women’s experiences (Miller-McLemore 1999; Ruether 2009), as understanding forgiveness through wives’ perspectives is crucial to better grasp its complexity (Norlock 2018). Finally, since forgiveness is a process that evolves (Fincham et al. 2006), this study adopts a 15-year longitudinal research approach to investigate the long-term dynamics of wives’ forgiveness behaviors.

This research seeks to fill the gap in studies on forgiveness following infidelity within the Chinese cultural context and, through a gender perspective and long-term research, provide new insights into the changes in wives’ forgiveness in marriages affected by infidelity. These findings will help expand the scope of forgiveness theory and offer a valuable reference for future gender studies and marital counseling practices.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Definition and Types of Forgiveness

Forgiveness is typically regarded as something good and virtuous. Robert Enright, hailed as “the forgiveness trailblazer” by Time Magazine and his colleagues, defined forgiveness as the willingness to relinquish resentment and negative judgment and behave impartially toward those who have unjustly harmed us (Enright and Coyle 1998). This definition has been widely accepted. Worthington (2005) further explained that in enduring and meaningful relationships, such as marriage, forgiveness must involve two components: (a) letting go of negative experiences, and no longer holding the offender’s unjust behavior against them, and (b) developing positive feelings toward the offender. In situations of significant relational harm, the two types of forgiveness—decisional forgiveness and emotional forgiveness—offer insight into explaining this complex and time-consuming process.

Decisional forgiveness refers to a person’s intention to treat the offender as they did before the offense, while emotional forgiveness involves letting go of resentment, replacing it with positive thoughts, feelings, motivations, and behaviors (Fincham et al. 2004; Worthington 2003; Worthington 2005). Someone can extend decisional forgiveness yet still feel emotionally unsettled (Worthington and Scherer 2004). For instance, after an affair, a wife may decide to stay in the marriage and maintain surface-level harmony (this reflects decisional forgiveness). However, she may continue to feel anger and pain internally, indicating that emotional forgiveness has not yet occurred. Meyer (2000) pointed out that such contradictory feelings are real. The statement “I forgive you, but I’m still angry” is not contradictory. Forgiveness and resentment often coexist. This situation and process have given rise to many discussions, including distinctions between pseudo-forgiveness, genuine forgiveness, and conditional and unconditional forgiveness.

Early on, Enright (2001) championed the concept of genuine forgiveness, carefully distinguishing it from pseudo-forgiveness and conditional forgiveness. He argued that genuine forgiveness is an act of goodwill that comes from within and is an unconditional gift. Unconditional in this context means the victim can forgive independently of the offender’s actions (Prieto-Ursúa et al. 2018). However, some scholars contend that pseudo-forgiveness is common in intimate relationships, and becomes a convenient strategy for maintaining the relationship by overlooking wrongdoing and moving forward. Self-protective motivations often drive this behavior (i.e., safeguarding the relationship). However, because both parties have not genuinely reached forgiveness, this strategy may eventually harm the relationship and sow seeds of future conflict, resentment, or emotional dissatisfaction (Sheldon and Antony 2018). The belief in conditional forgiveness suggests that the offender must meet certain conditions (e.g., demonstrating remorse) before the victim can forgive (Prieto-Ursúa et al. 2018). Some scholars argue that couples widely practice conditional forgiveness (Waldron and Kelley 2005). In severe conflict within intimate relationships, conditional forgiveness may be the only realistic option (Kloeber and Waldron 2017).

In response to these varying perspectives on forgiveness, Wang (2014) proposed five types of forgiveness for marital infidelity: Manipulative Forgiveness, Expressed Forgiveness, Expected Forgiveness, Well-Deserved Forgiveness, and Fully Surrendered Forgiveness. She categorized these types based on their intentionality and spontaneity, with the first three types being pseudo-forgiveness and the latter two being genuine forgiveness. According to Wang, willingness and decisional forgiveness are merely the starting points. Decisional forgiveness may lead to pseudo-forgiveness, where negative emotions are suppressed, and false goodwill is expressed, failing to bring inner peace or genuine relational harmony. Genuine forgiveness, on the other hand, is lasting and stable and involves overcoming one’s anger and transforming it into genuine goodwill and love.

Forgiveness is a complex concept and a time-consuming process. Understanding the mindset of wives who decide to forgive their unfaithful husbands, and the evolving process that leads to pseudo-forgiveness or genuine forgiveness over time, requires in-depth and long-term exploration and understanding.

2.2. Forgiveness and the Offender’s Subsequent Behaviors

Although “radical forgiveness” emphasizes “wiping away the guilt of others” and abandoning demands for reparation, this type of forgiveness involves self-sacrifice within systemic injustice and gender expectations. From a feminist perspective, society often regulates women through gendered mechanisms, requiring them to offer such forgiveness. However, this type of forgiveness involves moral justification and compromises personal dignity (Gedge 2010). Therefore, this study aims to explore instead how the offender’s subsequent behaviors impact forgiveness. Forgiveness arises because one person has committed an offense and caused harm. While the decision and implementation of forgiveness are part of the victim’s journey, they are still influenced by the offender’s subsequent actions. Fincham et al. (2006) stated that forgiveness involves personal and interpersonal elements. Lawler-Row et al. (2007) emphasized that forgiveness is an internal and relational process, particularly highlighting that the offender’s goodwill behaviors can help the victim passively let go of negative experiences, leading to better forgiveness outcomes. However, compared to the victim’s internal journey, the offender’s behaviors post-offense are less frequently discussed. A recent study by Côté et al. (2021) reviewed 35 articles on forgiveness and couple interventions, revealing that forgiveness is a complex, iterative, and non-linear process requiring significant involvement from both partners. Thus, the offender’s behavior in maintaining the post-offense relationship is worthy of further exploration.

2.2.1. Apologies

Many studies have pointed out that the severity of the offense (Kemp and Chen 2015; Scuka 2015) and the offender’s intent and attribution of responsibility (Fincham 2000; Leunissen et al. 2013) affect forgiveness. Marital infidelity, being a severe transgression, can cause significant harm. Victims often evaluate its severity based on its intensity, duration, and context. If the infidelity is perceived as deliberate (e.g., “He knew it would hurt me, but he did it anyway”), forgiveness becomes much more challenging (Côté et al. 2021). In such cases, the offender’s apology can be a critical behavior that facilitates forgiveness (Fehr and Gelfand 2010), as it signifies a willingness to acknowledge wrongdoing. However, apologies may sometimes be vague or deceptive rituals, lacking genuine meaning (Smith 2008). For an apology to be effective, it must align with the victim’s perception (Fehr and Gelfand 2010) and be perceived as sincere and helpful (Kemp et al. 2021), giving the impression that the issue can be corrected (Kim et al. 2009). Thus, a sincere apology that promotes forgiveness and rebuilds trust after marital infidelity should include expressions of guilt, acknowledgment of responsibility (Dillow and Denes 2022), and an implicit promise not to re-offend (e.g., a husband who apologizes after an affair, admits his mistake, and promises not to repeat it; if he continues to engage in infidelity, the apology will be perceived as superficial and insincere).

2.2.2. Restorative Actions

The unfaithful partner should take vital actions to address the harm caused to their spouse and the marital relationship, aiming to reduce damage and repair the relationship. Post-offense relationship restoration requires the offender to take responsibility for their actions, acknowledge their role as the offender, and engage in corrective behaviors beneficial to the victim to restore the relationship (Thai et al. 2023). It is emphasized that because the offender initiated the conflict, caused the harm, and created the disruption, they must also engage in restorative and compensatory actions. This is a form of accountability and may lead to exoneration. Corlett (2006) noted that not every offense needs to be punished; if the offender’s compensation and clear indication can resolve the issue more effectively, they may be forgiven and exempt from punishment.

Restorative actions show the offender’s care for the relationship, reducing the victim’s negative perceptions and reframing the offense in a less harmful context (Martinez-Diaz et al. 2021). Offenders must recognize the victim’s pain and fully understand the impact of their actions, both cognitively and emotionally. This can facilitate forgiveness if they can listen to the victim’s pain with empathy and acceptance (McKinnon and Greenberg 2017). Zuccarini et al. (2013) found that the victim’s secondary emotional responses (such as angry accusations or numb withdrawal) influence their interactions. If the offending partner ignores or downplays the victim’s emotional pain, it hinders the processing of attachment-related emotions. Conversely, positive responses to the victim’s emotional pain and attachment distress can promote forgiveness and reconciliation. Since healing from infidelity is a lengthy and challenging process, the unfaithful partner may hope to move on quickly from the affair and become impatient with the victim’s lingering emotional pain and anger, which is a common obstacle to forgiveness (Fife et al. 2008).

2.2.3. Relational Caring Behaviors and Diverting Strategies

Relational caring behaviors are the offender’s expressions of goodwill towards the victim without directly addressing the offense. Diverting strategies involve justifying their behavior or downplaying its significance (e.g., after an affair, the husband may not discuss the affair or directly apologize, but he shows care for his wife when she is unwell (relational caring behavior) and tries to repair the relationship by buying her expensive gifts (diverting strategy); such actions may temporarily ease the wife’s emotions but do not truly resolve the issue and may hinder genuine forgiveness). According to Martinez-Diaz et al. (2021), relational caring and diverting strategies do not change the desire for revenge, and thus, do not facilitate genuine forgiveness. These two strategies are rarely mentioned in previous research, possibly because they are considered ineffective strategies involving denial and avoidance. However, they may still play a role in rebuilding trust. Kim et al. (2009) viewed the reconstruction of distrustful relationships as an interactive process. The formation of denial and avoidance strategies by offenders may be related to the relationship and power dynamics between both parties. Strong denial by the offender in response to the victim’s lack of reaction or weak assertion may achieve a certain degree of relationship repair. Conversely, strong denial in response to intense accusations from the victim can create a “strong confrontation” tension. In contrast, weak denial in the face of the victim’s withdrawal from assertion resembles avoidance and may result in a prolonged stalemate in the distrustful relationship.

In conclusion, the unfaithful husband’s subsequent restorative actions influence the wife’s forgiveness. The extent and direction of this influence depend on their interactions and the wife’s perception and reception of these behaviors. This process requires in-depth, longitudinal exploration to be fully understood.

2.3. Gender Perspectives and Forgiveness

Li et al. (2024) emphasized that in Chinese society, which values maintaining relationships, culture and gender play significant roles in forgiveness and marital dynamics. Some Western researchers have explored the influence of gender on forgiveness, with recent studies showing varying results. Some find men to be more forgiving than women (Cabras et al. 2022), while others suggest the opposite (Karniol and Čehajić-Clancy 2020; Miller and Worthington 2015; Witvliet et al. 2019). Additionally, some studies indicate that men exhibit higher levels of self-forgiveness (Kaleta and Mróz 2022), while others note that men are more tolerant in the early stages of marriage. However, this gender difference diminishes over time, eventually reversing, with women becoming more forgiving than men in marriage (Miller and Worthington 2010). This highlights the importance of examining longitudinal changes in marital forgiveness. Although this study does not focus on gender differences, it is essential to consider gender perspectives—such as cultural and social expectations, gender roles, and power dynamics—to gain a comprehensive understanding of Taiwanese women’s forgiveness after their husbands’ infidelity.

2.3.1. Cultural and Social Expectations

Culture involves the concepts of collectivism and individualism. Miller et al. (2008) noted that individualistic cultures are more sensitive to evaluations of injustice. Asians, on the other hand, lean towards collectivism, where kinship relationships have historically defined social interactions (Frost 2020). While Taiwan has recently been influenced by individualism, collectivist values remain deeply rooted, emphasizing kinship maintenance, social expectations, and the linkage between individual dignity and collective honor. “For Chinese people, we are sensitive to ‘face.’ Our self-system is often about ‘being seen by others’” (Yu 1992). Since Chinese culture values social perceptions, actions that hold positive value in others’ eyes will be adopted, while behaviors that may lead to criticism or blame will be avoided. Marriage and family are esteemed positive values in Chinese culture. Infidelity or divorce due to infidelity can generate collective pressure.

In a collectivist society, deviant behavior is often socially negotiated. Thus, society’s definition of the severity of male infidelity and the legitimacy of forgiveness reflects the expectation that the wife should forgive. Given Taiwan’s historical acceptance of polygamy, traditional culture may be more tolerant of male infidelity and place higher expectations on wives to forgive and maintain the marriage. This is rooted in a form of social expectation driven by collective culture.

2.3.2. Gender Role Expectations

Different cultures exhibit varying gender role expectations. Miller et al. (2008) cautioned that gender differences and cultural contexts can be confounding factors, as gender differences in forgiveness may stem from cultural differences. Female traits are often linked to forgiveness-related qualities, such as valuing relationships, possessing empathy, and being more emotionally sensitive. Kaleta and Mróz (2022) found that solid emotional control makes forgiving difficult for women. However, when women receive positive emotions and acceptance from their husbands, they are more likely to forgive. Another issue is that compared to forgiving others, women find it harder to forgive themselves, as they tend to internalize problems. This aligns with Taiwanese society’s expectations of women’s roles, where women are expected not only to blame their husbands but also to reflect on and examine themselves, attributing part of the infidelity issue to their shortcomings.

Traditional Chinese gender role expectations consider men as more aggressive and women as more nurturing and empathetic. Empathy has been shown by many studies to be associated with forgiveness. Karniol and Čehajić-Clancy (2020) found that women exhibit more empathy in resolving interpersonal conflicts, and Witvliet et al. (2019) specifically noted that women possess higher trait empathy (concern) and state empathy (perspective-taking), resulting in higher levels of interpersonal forgiveness. Since women are expected to show higher levels of empathy and demonstrate it, wives may also be expected to forgive their husbands in cases of infidelity.

Miller et al. (2008) pointed out that women are more inclined than men to maintain relationships, and this desire motivates them to forgive rather than pursue justice (through revenge or social mechanisms). Hoyt et al. (2005) provided a perspective on the multiple factors influencing forgiveness within families, particularly emphasizing the varying effects of different family roles on the forgiveness process. In Chinese family relationships, traditional gender roles influence spousal interactions. Men are typically seen as primary decision-makers or economic providers, while women take on more emotional support and caregiving roles. Since maintaining relationships is a primary role for wives and mothers, wives in marriages involving infidelity may be expected to demonstrate forgiveness, prioritizing the collective goal of family harmony over individual emotional well-being.

2.3.3. Gender Power Dynamics

Fincham et al. (2006) suggested that unequal power distribution in marriage affects forgiveness. The party with greater power is often less forgiving, as they have more opportunities for revenge, and relinquishing revenge means giving up their superior position. Conversely, the party with less power may be more forgiving, as their chances of revenge are limited, and failure to exact revenge only reinforces their lower position. Zheng and van Dijke (2020) further argue that when the victim holds greater power than the transgressor, the transgressor may perceive forgiveness as insincere, thereby reducing their motivation for relationship repair. From a broader perspective, transgressions, apologies, and forgiveness can be seen as issues of power and entitlement. Through interpersonal violations, transgressors assert dominance and control, often resulting in diminished agency on the part of victims (Woodyatt et al. 2022). Offering an apology may symbolically transfer power and control back to the victim (Okimoto et al. 2013). Thai et al. (2023) suggest that withholding forgiveness may function as a means for the victim to reassert power, potentially threatening the transgressor’s own sense of authority.

Based on this analysis, in traditional Taiwanese gender roles, husbands hold greater power within the family due to their gender and economic advantages. Whether a husband chooses to apologize may reflect his willingness to relinquish power. On the other hand, wives, who are often situated in a position of lesser power, may forgive not out of reconciliation but due to constrained opportunities for retaliation. However, refusing to forgive may also represent a strategy for reclaiming agency. However, as Taiwanese women’s income levels have risen through higher education and employment opportunities, these gender power dynamics remain subject to individual marital circumstances.

2.3.4. Feminism and Forgiveness

Although forgiveness offers many benefits, it is cautiously approached by feminist scholars (MacLachlan 2009). Indeed, forgiveness may carry ethical risks. First, forgiveness and justice often create particularly painful dilemmas in feminist thought, as forgiveness may imply that those being asked to forgive, especially if the harm they suffered is insufficiently acknowledged, may feel that such a demand diminishes their dignity and moral worth (Gheaus 2010). Forgiveness might allow the offender to evade justice, and it could strip the victim of their power to demand justice, which is both challenging and perilous, as it exploits the forgiving nature of women who are often too kind and vulnerable to unjust treatment (McNulty 2011). To prevent this loss of justice power, Anderson (2016) even suggests that women who have experienced intimate partner violence should reject forgiveness in the process of healing.

Furthermore, many requests for forgiveness overlook the gendered history of so-called virtues. Haaken (2002) argues that forgiveness has been “feminized,” casting women as embodiments of unconditional love, even expecting them to remain loving and forgiving in the face of a husband’s infidelity. Additionally, women are idealized as caretakers and peacekeepers within the family, with these societal expectations centering around their roles in domestic life, shaping the notion that women must forgive. From this perspective, the expectation of women’s forgiveness becomes another form of oppression. While women’s capacity for forgiveness is often seen as admirable and socially recognized, men are less likely to be held to this expectation; instead, forgiveness in men is often associated with weakness (Konstam et al. 2001).

These are critical aspects we must consider when exploring forgiveness. Norlock (2018) reminds us that “gender is at the heart of forgiveness,” and the feminist notion that “the personal is political” encourages us to focus not only on women’s experiences but also on the power dynamics between the offender and the victim. Furthermore, we must account for the family, social, and cultural expectations of women’s forgiveness to understand the complexity of forgiveness fully.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Hermeneutic Phenomenology

This study is grounded in the philosophical principles of hermeneutic phenomenology, which emphasizes pre-understanding, the hermeneutic circle, and the fusion of horizons. It provides a step-by-step strategy that ensures the rigor and credibility of research (Alsaigh and Coyne 2021). When facing a husband’s infidelity and subsequent behaviors, each wife experiences it in a uniquely personal way. The researcher must enter the wives’ world and understand their experiences from their subjective perspectives, interpreting the authenticity of these experiences through meaning construction. Hermeneutic phenomenology involves both empirical activities (data collection) and reflective activities (meaning analysis) (Fuster Guillén 2019). This approach requires the researcher to remain constantly aware of their involvement during the research and interpretation processes and to take responsibility for the meanings constructed. Since understanding is inherently situated, the researcher must engage in self-reflection as part of the interpretive process. This methodology aligns with feminist and women-centered perspectives, returning to women’s experiences (Ruether 2009). It emphasizes interpreting women’s realities through their self-reported stories and experiences, which enables the emergence of new knowledge and ways of action.

3.2. Participants

The study participants were wives who had experienced their husbands’ infidelity. Considering the nuances of Taiwanese culture (where some wives may not be fully aware of the details of their husbands’ affairs), this research did not limit participants based on whether the infidelity involved sexual or emotional elements. As long as the wives subjectively recognized the infidelity, regardless of its nature or how long ago it occurred, they met the criteria for this study.

In 2009, snowball sampling was employed to reach eligible participants, resulting in initial interviews with nine participants. In 2014, using an intensity sampling strategy, five participants who showed strong interest in the phenomenon were selected and provided rich information for continuous interviews. In 2024, a third round of interviews was conducted with these five participants. Their ages range from 51 to 63; three remain married, while two divorced during the research period. Table 1 provides a summary of the participant information, ensuring privacy protection.

Table 1.

Summary of research participants.

3.3. Procedure

This study employed in-depth individual interviews for data collection. Establishing a rapport with participants was prioritized during the interview process. As an essential research tool, the researcher aimed to be a good interviewer by showing respect, acceptance, clear communication, and attentive listening while maintaining a natural conversational style that followed the participants’ logic and pace, ensuring a smooth storytelling flow.

After completing each interview, the researcher transcribed the recordings into verbatim transcripts, and the data analysis began with coding the conversations. This process involved examining the contextual trends, structuring themes, and extracting meaningful units from the data. The first round of interviews was completed in 2009, followed by the initial research report provided to the participants for review. This step strengthened the participants’ recognition of and confidence in the research, encouraging them to continue contributing to the 15-year study. Each participant underwent 3–6 interviews over the 15 years, with each session lasting approximately 70–120 min. It is worth mentioning that this study adhered to ethical principles, including respect for participants and informed consent. The participants were fully informed about the study’s purpose, the interview content, the procedures, and their right to withdraw at any time. All information related to the participants was anonymized in the report to protect their privacy.

4. Results

4.1. Husband’s Behavior After Infidelity and the Wife’s Pseudo-Forgiveness

The husband’s behavior after infidelity is closely related to the wife’s initial forgiveness response. Regardless of whether the husband’s actions are positive or negative, due to the severity of marital crises such as infidelity, the wife’s initial expression of forgiveness often manifests as a form of pseudo-forgiveness—suppressing strong negative emotions while outwardly expressing forgiveness for other reasons.

4.1.1. Husband’s Behavior After Infidelity: Towards the Wife, Affair, and Family

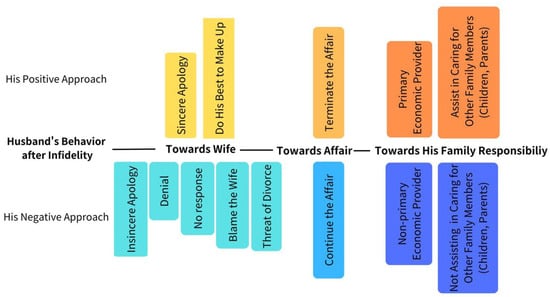

This study categorizes the husband’s post-affair behaviors into three dimensions: toward the wife, toward the affair, and his family responsibility. These can be further divided into positive and negative orientations (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Husband’s behavior after infidelity.

- “Towards the Wife”:

Positive behaviors include sincere apologies and doing his best to make up. Apologies play a significant role in helping the wife process the infidelity and reduce negative emotions. A heartfelt apology conveys the offender’s acknowledgment of harm, recognition of the spouse’s suffering, and the expression of regret or remorse (Cloke 2015). For the apology to be effective, it must be accompanied by genuine compensatory behaviors, such as providing emotional and physical support and actively avoiding environments that may trigger the affair.

Not every wife receives an apology. When a husband’s apology is followed by behaviors that doubt his sincerity, such apologies are considered insincere and harmful. Negative behaviors “towards the wife” include insincere apologies, denial, no response, blaming the wife, and using the threat of divorce.

- 2.

- Regarding the husband’s actions “Towards the Affair”:

These are simplified into two types: terminating or continuing the affair. The wife assesses whether the husband has indeed ended the affair based on his willingness to disclose his whereabouts and cut ties with the third party, or whether signs of the affair, such as contact or unclear explanations, persist. In some cases, the wife learns that the affair continues through confrontations with the third party.

- 3.

- “Towards His Family Responsibility”:

This involves the husband’s commitment to his familial roles, particularly in Chinese cultural values that emphasize family roles and responsibilities. The study participants collectively stated that the husband’s commitment to fulfilling his family responsibilities is crucial. Although the affair itself may be hard to accept, if the husband remains responsible for family duties, such as being the primary economic provider and caring for other family members (including children and parents), it can demonstrate his positive attributes and mitigate the perceived harm caused by the affair.

Traditional Chinese gender roles emphasize “men as breadwinners and women as homemakers,” indicating that men are responsible for providing for the family. Historically, a Chinese man could have multiple wives, provided he could financially support them. Although gender equality is advocated in modern times, the participants in this study expressed that the husband’s ability to provide economic support to the family remains significant. This financial contribution elevates the husband’s status within the family and influences the wife’s more positive perception of him.

4.1.2. Husband’s Behavior After Infidelity and Marital Power

Marital power stems from multiple sources. The most visible form is positional power—objectively measurable resources such as income, education, and occupational status—which often shape decision-making authority within the family (Blanton and Vandergriff-Avery 2001; Körner and Schütz 2021). In East Asian societies, where extended family structures are common, marital power is also shaped by intergenerational resources and familial influence, rather than individual capacity alone (Cheng and Xie 2023). Recent studies have also emphasized relational power—influence derived from emotional dynamics, communication skills, and referent power. Even when women lack structural resources, they may still exert meaningful influence through relationship-based strategies (Blanton and Vandergriff-Avery 2001; Kyei et al. 2024).

In this study, the wife’s marital power was assessed based on three dimensions: (1) whether she was the primary economic provider, (2) her level of education and occupational status relative to her husband’s, and (3) her role in household decision-making. While positional power served as the main criterion, relational indicators—such as emotional agency and interpersonal influence—were also considered in interpreting their marital position.

This study reveals that the husband’s positive or negative behavior post-affair is related to the power dynamics between the spouses. In marriages where the wife was perceived to hold more power, participants often described the husband as showing more constructive responses toward the wife and the affair following disclosure. Conversely, in accounts where the husband maintained greater control within the marriage, participants frequently described more avoidant or hostile responses from him after the affair. Additionally, the more positive the husband’s behavior towards family responsibilities, the more likely he would receive the wife’s goodwill. Especially in cases where the husband’s economic capacity surpassed the wife’s, his willingness to be the primary family provider was an essential factor in consolidating his family power and status.

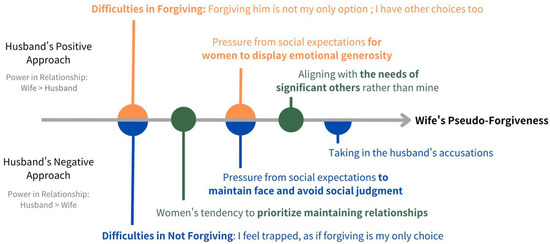

4.1.3. Factors Contributing to the Wife’s Pseudo-Forgiveness

The research indicates that the initial forgiveness formed by wives is often pseudo-forgiveness, which frequently involves suppressing negative emotions and falsely expressing goodwill. As a result, it fails to bring about true inner peace or genuine relational harmony (Wang 2014). This finding resonates with Norlock’s (2018) argument that the burden of forgiveness is heavier for women, as they are socially expected to forgive others more frequently. They are expected to resolve or avoid conflict, prevent harm to others, and avoid provoking anger. Consequently, they are more likely to display pseudo-forgiveness. The factors contributing to the formation of pseudo-forgiveness are summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Factors contributing to the wife’s pseudo-forgiveness.

In marriages where the husband holds more power, the wife, constrained by her lower power, forms pseudo-forgiveness due to three main factors:

- Difficulties in Not Forgiving—“I feel trapped, as if forgiving is my only choice”:

A wife with lower power does not see other options beyond forgiveness. She may feel she has nowhere to go, believe she cannot live independently, or fear she will not meet another better man. Additionally, she may find it difficult to imagine becoming a single mother. In summary, if leaving the marriage does not offer a better outcome, forgiving and accepting the unfaithful husband appears to be the only viable option.

- 2.

- Pressure from Social Expectations to Maintain Face and Avoid Social Judgment:

Maintaining face and avoiding criticism is crucial in a collective society. If the family is filled with conflicts or even breaks down, it results in a loss of face. This social expectation to maintain appearances also causes a wife with less power to hide or downplay the issue when facing her husband’s infidelity to avoid criticism and disappointment from others.

“I told my husband that I could only consider divorcing him if my father passed away… I couldn’t let my father lose face or feel hurt.”[Chris 2009]

- 3.

- Taking in the Husband’s Accusations:

When confronted with the husband’s criticism, A wife with lower power may internalize her accusations, believing that her mistakes led to the affair. As the wife engages in self-blame, the unfaithful husband’s wrongdoings are minimized, leading the wife to suppress her emotions and enter into a state of pseudo-forgiveness.

For a wife with greater power, there are two contributing factors to pseudo-forgiveness:

- Difficulties in Forgiving—“Forgiving him is not my only option; I have other choices too.”:

Due to her higher power, it is harder for a wife to accept her husband’s infidelity. With the ability to lead a good life independently, she may question why she must forgive him. However, the husband’s sincere apology and compensatory efforts may temporarily suppress negative emotions, resulting in pseudo-forgiveness.

- 2.

- Pressure from Social Expectations for Women to Show Emotional Generosity:

Society’s expectation that women be forgiving and empathetic pressures a wife to offer forgiveness.

“Even though I was very angry with him, he truly tried to make amends… I wondered, shouldn’t I be more forgiving? Shouldn’t I forgive someone who sincerely admits his mistake and apologizes?”[Anne 2009]

Additionally, two universal factors unrelated to power dynamics also contribute to the formation of pseudo-forgiveness:

- Women’s Tendency to Prioritize Maintaining Relationships:

A wife aims to maintain family harmony and avoids breaking family structures. This tendency drives her to suppress personal negative emotions, even resorting to denial or self-deception in the aftermath of the affair.

- 2.

- Aligning with the Needs of Significant Others Rather than Their Own:

Significant others, primarily children and sometimes parents, play a crucial role in women’s decision-making. The importance of the mother’s role often surpasses individual needs. There is a saying in Chinese culture, “For the sake of being a mother, she must be strong.” For the sake of the children, women must find ways to overcome the trauma of the affair.

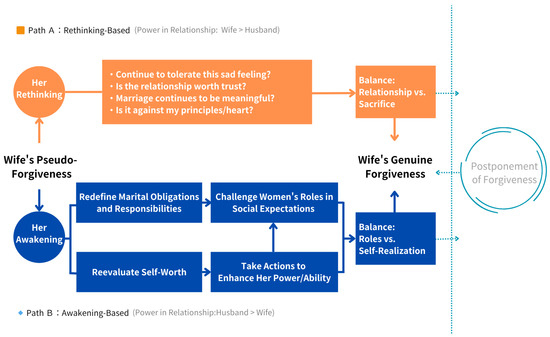

4.2. Transition from Pseudo-Forgiveness to Genuine Forgiveness

This 15-year longitudinal study provided the opportunity to observe the wife’s transition from pseudo-forgiveness to genuine forgiveness. This process is influenced by the husband’s behavior after the affair and the power dynamics within the marriage, leading to different pathways (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The wife’s pathways to genuine forgiveness.

4.2.1. Pathway to Genuine Forgiveness: Marriages Where Wife Holds More Power

In marriages where the wife holds more power, the affair not only severely impacts the marital relationship but also prompts the wife to enter a process of “Her Rethinking,” which includes:

- “Continue to tolerate this sad feeling?”:

Even if the husband sincerely apologizes and makes amends, the negative emotions and thoughts triggered by the affair are overwhelming. Pseudo-forgiveness may appear to provide temporary relief to the marital relationship, but the wife’s internal struggle with negative emotions continues. A wife with sufficient economic independence and social status may question why she should tolerate such sadness if she has the means to live a better life.

- 2.

- “Is the relationship worth trusting?”

Loyalty is highly valued in a relationship where the wife’s power surpasses the husband’s. The affair destroys her expectations and trust in the relationship. Even though the husband’s repentance evokes her empathy, she may doubt whether the relationship can regain trust.

- 3.

- “Does marriage continue to hold meaning?”:

The wife contemplates whether she still wants to continue with the marriage. A wife with greater power usually has the means to bear the cost of ending the marriage. This deeper reflection is not only emotional but also a reevaluation of the direction of their life.

- 4.

- “Is it against my principles/heart?”:

A high-power wife often has her bottom line and principles. If she chooses to forgive her husband, will it go against her principles or betray her true feelings? A wife does not want to compromise easily. If forgiveness does not align with her heart, the marriage will only become more stifling.

“I asked myself, why am I forgiving him? Is it because I truly want to, or is it due to outside pressure… because of the children? Or to save face? Am I being too self-sacrificing?”[Anne 2014]

A high-power wife continually re-evaluates her emotions, cognition, and the realities of her life through a process referred to as “Her Rethinking.” This reflection ultimately leads her toward seeking a balance between marital relationship and non-self-sacrifice, wherein she hopes to find a way that neither compromises her sense of self nor forecloses the possibility of mending the relationship. If she chooses to forgive her husband in this process, it will not be out of self-denial or repression but rather from a place of genuine, heartfelt “genuine forgiveness.”

The ongoing process of reflection may lead to a new state termed “Postponement of Forgiveness,” where the wife redefines the boundaries and expectations of the relationship, shifting beyond the binary choice of “to forgive or not.”

“For many years, I never really thought about his affair again. But during the days when I was preparing for divorce, I realized that the affair had already pushed me to build emotional boundaries. I had made myself emotionally independent, so he could no longer hurt me the way he did.”[Anne 2024]

4.2.2. Pathway to Genuine Forgiveness: Marriages Where the Wife Holds Less Power than the Husband

In traditional Chinese marriages where the husband holds more power, a wife is often constrained by traditional marital values and gender role expectations. However, with the influence of marital equality, when a wife begins to question, “Why must I adhere to marital commitments while the husband is free to violate them?” She may challenge existing social norms and start an “Awakening” process. This includes:

- “Redefining Marital Obligations and Responsibilities”:

A wife begins to question whether she needs to be bound by such an unequal relationship, leading to a stage of “Challenging Women’s Roles in Social Expectations.” Traditionally, women are expected to endure and show tolerance in the face of marital difficulties. When the wife starts to challenge these expectations, she redefines her role.

- 2.

- “Reevaluating Self-Worth”:

Traditionally, a woman’s worth post-marriage is defined by her role as a wife and mother. For a wife with less power, her husband’s infidelity not only causes emotional hurt but also delivers a blow to her sense of self-worth, as she feels like a failed wife. But when the wife awakens and asks herself, “Why did this happen to me?” and “What does this mean for me?” This exploration of self-worth and awakening empowers the wife to make decisions that better align with her inner desires.

“Through the meditation course, I was able to release my emotions. I wanted to understand more clearly what I really needed for myself.”[Elle 2014]

A wife will then “Take Actions to Enhance Her Power/Ability” to fulfill better what she sees as an essential role. A wife with less power may engage in activities such as returning to school (to improve educational attainment), excelling at work (to enhance her position and income), or participating in support groups (to increase her sense of value). These actions lead to new self-identity and self-worth, further empowering her to “Challenge Women’s Roles in Social Expectations.”

“I wanted my children to grow up in a stable family, no matter what their father did… So I went back to school, earned my degree, and became a teacher. Now both of my kids study at the school where I teach. I’ve taken students to science fairs and won awards five years in a row—even took a photo with the president. This is the version of myself that I wanted.”[Dora 2024]

These pathways are not just about empowerment but about transformation. They lead the wife toward “Balancing Marital Roles and Self-Realization.” As she gains a sense of capability and power, she becomes more autonomous and can choose her marital role or pursue her freedom and happiness. This transformation is not just a response to the unfaithful husband but a process of pursuing self-balance. It is a journey from “pseudo-forgiveness” to “genuine forgiveness,” a journey that is not forced but a result of her autonomous choice.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The gender perspective provides a crucial framework for understanding how husbands’ post-affair behaviors influence their wives’ forgiveness. By adopting a gender perspective, this study examines how cultural and gender roles, social expectations, and power dynamics shape wives’ forgiveness. The findings reveal that the husband’s behaviors after infidelity are categorized into “Towards Wife,” “Towards Affair,” and “Towards His Family Responsibilities,” with both positive and negative approaches—which are closely related to the power dynamics between the spouses. Taiwanese wives, when faced with issues of infidelity and forgiveness, are often confronted with additional pressures and burdens stemming from cultural and gender norms, as well as social expectations. These include cultural values that emphasize collectivism and the avoidance of negative evaluations (saving face), the cultural emphasis on family values (family integrity), the expectation that women should prioritize maintaining relationships (preventing family breakdown), social expectations for women to be understanding and tolerant, and the notion that women should sacrifice themselves for the welfare and needs of others. Wives with lower power in the marriage often face more criticism and blame from their husbands. They may be compelled to accept responsibility for the affair’s occurrence and consequences, considering the practical difficulties they might encounter if they choose not to forgive. These factors may lead wives to compromise and initially adopt “pseudo-forgiveness” to respond to their husband’s affairs.

This study proposes pathways to “genuine forgiveness” for wives with high and low power. Husbands’ infidelity prompts high-power wives to enter the “Her Rethinking” phase, a journey of self-discovery and empowerment. This phase leads to the “Balance Marital Relationship and Non-Self-Sacrifice” stage, a testament to the resilience and strength of these wives, which ultimately results in “genuine forgiveness.” On the other hand, husbands’ infidelity pushes low-power wives into the “Her Awakening” phase, a process of self-realization and empowerment, followed by the stages of “Challenge Women’s Roles in Social Expectations” and “Take Actions to Enhance Her Power/Ability,” which reflect a journey of empowerment and self-discovery; they eventually reach the “Balance Marital Roles and Self-Realization” stage, which can also lead to “genuine forgiveness.” These two pathways indicate that for wives to move towards “genuine forgiveness,” they must feel empowered and capable. “Genuine forgiveness” is an active and spontaneous personal choice that is distinctly different from “pseudo-forgiveness,” which is influenced by external pressures. This research echoes the feminist advocacy that forgiveness should not become a gender-related mandatory obligation, forcing women to display more emotional tolerance, which would only increase their psychological burden, and neglects the dignity women should maintain in the process of forgiveness. On the contrary, forgiveness is a self-determined decision (McKay et al. 2007), and this study highlights two pathways leading to the essence of “genuine forgiveness.”

A husband’s sincere apology and subsequent compensatory actions can help shorten the path to “genuine forgiveness.” However, enhancing low-power wives’ power is often complicated and time-consuming. Without positive responses and support from the unfaithful husband, the sustaining forces behind this process are worth further exploration.

Furthermore, as gender equality advances in Taiwan, modern wives are placing more emphasis on self-worth and dignity when confronting a husband’s infidelity, whether they hold high or low power. This increased self-reflection and awakening during the process of forgiveness makes them more cautious. They are more inclined to observe or demand concrete behavioral changes from their partner before choosing forgiveness. Therefore, this study proposes the “Postponement of Forgiveness” (Figure 3). Whether to forgive the husband is temporarily set aside at this stage, and it is possible that “genuine forgiveness” may develop afterward. The form and trajectory of this process deserve further investigation in future studies. Moreover, this research result might indicate that modern wives’ concept of forgiveness is shifting from traditional unconditional to conditional forgiveness.

It is worth mentioning that the two pathways toward “genuine forgiveness” are processes of self-empowerment for wives. This research affirms the importance of empowerment and responds to Kausar (2022), who suggests that all cultures have the right to reinterpret and pursue women’s empowerment according to their values. Taiwanese wives empowered through self-actualization gradually make choices based on the values they deem important. The study finds that Taiwanese wives emphasize their role as mothers, regardless of whether they choose to divorce or continue the marriage. They aim to improve their ability to provide the best life for their children and work toward that goal. Additionally, after enhancing their economic independence, Taiwanese wives are less likely to accept infidelity from husbands who fail to contribute financially to the family, and this increases the likelihood of divorce.

This present study has several limitations. First, while the hermeneutic phenomenological approach with a small sample allowed for a deep exploration of wives’ experiences, the limited number of participants means the findings cannot be generalized. As with all interpretive qualitative research, the findings represent situated interpretations rooted in participants’ cultural and relational contexts, rather than objective truths to be generalized. Second, this study did not distinguish between emotional and physical infidelity. In Taiwanese culture, many wives choose not to pursue details, and husbands often avoid admitting specifics. Without clear evidence, the nature of the affair remains vague. Our analysis was based on how participants themselves understood and felt about the betrayal. Future studies could explore how different types of infidelity influence forgiveness, and how culture shapes this ambiguity. Third, this study focused only on wives’ perspectives. Without the husbands’ voices, the understanding of how forgiveness unfolds between partners is limited. Future research could include both sides for a fuller view. Lastly, this research began 15 years ago, when online or cyber infidelity was not yet common. Since none of the participants mentioned such experiences, this issue was not explored. Future work could look at how digital relationships affect trust and forgiveness today. Furthermore, as all participants were aged 50 to 65 in the final interviews, the findings may not reflect the views or experiences of younger generations. Further studies could focus on younger couples, who might have different expectations shaped by changing gender roles.

The findings of this study have meaningful implications for marital counseling and welfare provision. Marital counselors can guide wives in reflecting and awakening, helping them explore the conflicts between culture, gender, social expectations, and personal values. The research results can assist wives in understanding that genuine forgiveness in cases of infidelity must come from personal choice rather than external pressure. Practical empowerment methods (including education, financial independence, selfless actions, and other welfare policies that protect financially disadvantaged spouses) enhance wives’ ability to make more informed choices when facing infidelity and marital challenges.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, as it only involved procedures deemed sufficient with the use of a consent form voluntarily filled out by all informants. The data used in my study was collected between 2008 and 2009. At that time, institutional review board (IRB) approval was not yet a standardized or required procedure in Taiwan for qualitative research in the humanities documents issued by Taiwan’s national research authorities.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are not publicly available due to privacy and confidentiality agreements with the participants.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to express their sincere gratitude to the five research participants, for their invaluable contributions and commitment to this study. Their participation and insights were essential to the success of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Alsaigh, Ranya, and Ines Coyne. 2021. Doing a Hermeneutic Phenomenology Research Underpinned by Gadamer’s Philosophy: A Framework to Facilitate Data Analysis. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 20: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Pamela S. 2016. When Justice and Forgiveness Come Apart: A Feminist Perspective on Restorative Justice and Intimate Violence. Oxford Journal of Law and Religion 5: 113–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betzig, Laura. 1989. Causes of Conjugal Dissolution: A Cross-Cultural Study. Current Anthropology 30: 654–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanton, Priscilla W., and Maria Vandergriff-Avery. 2001. Marital Therapy and Marital Power: Constructing Narratives of Sharing Relational and Positional Power. Contemporary Family Therapy 23: 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabras, Carla, Kamila Kaleta, Justyna Mróz, Giulia Loi, and Carlo Sechi. 2022. Gender and Age Differences in Forgivingness in Italian and Polish Samples. SSRN Electronic Journal 8: e09771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Chao-Ju. 2013. Still Unequal: The Difficulties and Unfinished Business of Feminist Legal Reform of the Patriarchal Family. Journal of Women’s and Gender Studies 33: 119–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Yu-Ting. 2016. The Transformation of “Adultery” News and Related Discourses in the Newspaper: A History of Intimacy Relationship and Gender Politics, 1950s–1990s. Master’s thesis, Kaohsiung Medical University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan. Available online: https://www.airitilibrary.com/Article/Detail?DocID=U0011-2208201602083800 (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Cheng, Cheng, and Yu Xie. 2023. Towards an Extended Resource Theory of Marital Power: Parental Education and Household Decision-Making in Rural China. European Sociological Review 40: 802–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloke, Kenneth. 2015. Designing Heart-Based Systems to Encourage Forgiveness and Reconciliation in Divorcing Families. Family Court Review 53: 418–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corlett, J. Angelo. 2006. Forgiveness, Apology, and Retributive Punishment. American Philosophical Quarterly 43: 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Côté, Marie, Julie Tremblay, and Mathieu Dufour. 2021. What Is Known about the Forgiveness Process and Couple Therapy in Adults Having Experienced Serious Relational Transgression? A Scoping Review. Journal of Couple & Relationship Therapy 21: 207–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillow, Megan R., and Amanda Denes. 2022. Forgiveness for a Partner’s Infidelity. In The Oxford Handbook of Infidelity. Edited by Tara DeLecce and Todd K. Shackelford. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 415–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enright, Robert D. 2001. Forgiveness Is a Choice. Washington: APA Life Tools. [Google Scholar]

- Enright, Robert D., and Catherine T. Coyle. 1998. Researching the Process Model of Forgiveness within Psychological Interventions. In Dimensions of Forgiveness. Edited by Everett L. Worthington. Radnor: Templeton Foundation Press, pp. 139–62. [Google Scholar]

- Fehr, Ryan, and Michele J. Gelfand. 2010. When Apologies Work: How Matching Apology Components to Victims’ Self-Construals Facilitates Forgiveness. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 113: 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fife, Stephen T., Gerald R. Weeks, and Nancy Gambescia. 2008. Treating Infidelity: An Integrative Approach. The Family Journal 16: 316–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fincham, Frank D. 2000. The Kiss of the Porcupines: From Attributing Responsibility to Forgiving. Personal Relationships 7: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fincham, Frank D., Julie Hall, and Steven R. H. Beach. 2006. Forgiveness in Marriage: Current Status and Future Directions. Family Relations 55: 415–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fincham, Frank D., Steven R. H. Beach, and Joanne Davila. 2004. Forgiveness and Conflict Resolution in Marriage. Journal of Family Psychology 18: 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, Peter. 2020. The Large Society Problem in Northwest Europe and East Asia. Advances in Anthropology 10: 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuster Guillén, Doris Elida. 2019. Qualitative Research: Hermeneutical Phenomenological Method. Propósitos y Representaciones 7: 201–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedge, Elisabeth. 2010. Radical Forgiveness and Feminist Theology. In A Journey Through Forgiveness. Edited by Malika Rebai Maamri, Nehama Verbin and Everett L. Worthington, Jr. Leiden: Brill, pp. 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheaus, Anca. 2010. Is Unconditional Forgiveness Ever Good? In New Topics in Feminist Philosophy of Religion. Edited by Pamela Sue Anderson. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haaken, Janice. 2002. The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly: Psychoanalytic and Cultural Perspectives on Forgiveness. In Before Forgiving: Cautionary Views of Forgiveness in Psychotherapy. Edited by Sharon Lamb and Jeffrie G. Murphy. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 172–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyt, William T., Frank D. Fincham, Michael E. McCullough, Gregory R. Maio, and Joanne Davila. 2005. Responses to Interpersonal Transgressions in Families: Forgivingness, Forgivability, and Relationship-Specific Effects. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 89: 375–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hwong, Shu-Ling, Tony Szu-Hsien Lee, and Yun-Chin Chao. 2012. Sexual Attitudes and Values in Taiwan: Differences among Gender, Cohort, and Three Cluster Groups. Formosan Journal of Sexology 18: 83–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaleta, Kinga, and Justyna Mróz. 2022. Gender Differences in Forgiveness and Its Affective Correlates. Journal of Religion and Health 61: 2819–2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karney, Benjamin R., and Thomas N. Bradbury. 2020. Research on Marital Satisfaction and Stability in the 2010s: Challenging Conventional Wisdom. Journal of Marriage and Family 82: 100–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karniol, Rachel, and Sabina Čehajić-Clancy. 2020. A Gendered Light on Empathy, Prosocial Behavior, and Forgiveness. In The Cambridge Handbook of the International Psychology of Women. Edited by Fanny M. Cheung and Diane F. Halpern. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 221–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kausar, Zeenath. 2022. Women’s Empowerment in UN Documents Neither a Safe Haven nor a Pandora’s Box: Need for a Holistic Perspective. International Journal of Islamic Thought 21: 128–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, Simon, and Zhe Chen. 2015. When Things Go Wrong: Lay Perceptions of Blame. Asia Pacific Management Review 20: 184–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, Simon, Zhe Chen, and Ailsa Humphries. 2021. Reactions to Admissions of Wrongdoing. New Zealand Journal of Psychology 50: 4–12. Available online: https://www.psychology.org.nz/application/files/4216/2372/2902/Kemp_4-12.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Kim, Peter H., Kurt T. Dirks, and Cecily D. Cooper. 2009. The Repair of Trust: A Dynamic Bilateral Perspective and Multilevel Conceptualization. Academy of Management Review 34: 401–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloeber, Dayna N., and Vincent R. Waldron. 2017. Expressing and Suppressing Conditional Forgiveness in Serious Romantic Relationships. In Communicating Interpersonal Conflict in Close Relationships: Contexts, Challenges, and Opportunities. Edited by Jennifer A. Samp. New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group, pp. 250–66. [Google Scholar]

- Konstam, Varda, Miriam Chernoff, and Sara Deveney. 2001. Toward Forgiveness: The Role of Shame, Guilt, Anger, and Empathy. Counseling and Values 46: 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Körner, Robert, and Astrid Schütz. 2021. Power in Romantic Relationships: How Positional and Experienced Power Are Associated with Relationship Quality. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 38: 2653–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyei, Simon, Bright Agorkpa, Beatrice Benewaa, and Nora Shamira Narveh Sadique. 2024. Marital Power Play in Patriarchal Society: A Qualitative Study of Ghanaian Religious Wives’ Perspectives. Discover Global Society 2: 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawler-Row, Kathleen A., Cynthia A. Scott, Rachel L. Raines, Meirav Edlis-Matityahou, and Erin W. Moore. 2007. The Varieties of Forgiveness Experience: Working toward a Comprehensive Definition of Forgiveness. Journal of Religion and Health 46: 233–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leunissen, Joost M., David De Cremer, Chris P. Reinders Folmer, and Marius van Dijke. 2013. The Apology Mismatch: Asymmetries between Victim’s Need for Apologies and Perpetrator’s Willingness to Apologize. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 49: 315–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Qingyin, Jinxuan Guo, Ziyuan Chen, Xiaoyan Ju, Jing Lan, and Xiaoyi Fang. 2024. Reciprocal Associations between Commitment, Forgiveness, and Different Aspects of Marital Well-Being among Chinese Newlywed Couples. Family Process 63: 879–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacLachlan, Alice. 2009. Practicing Imperfect Forgiveness. In Feminist Ethics and Social and Political Philosophy: Theorizing the Non-Ideal. Edited by Lisa Tessman. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Diaz, Pilar, José M. Caperos, María Prieto-Ursúa, Elena Gismero-González, Virginia Cagigal, and María José Carrasco. 2021. Victim’s Perspective of Forgiveness Seeking Behaviors after Transgressions. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 656689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKay, Kevin M., Melanie S. Hill, Suzanne R. Freedman, and Robert D. Enright. 2007. Towards a Feminist Empowerment Model of Forgiveness Psychotherapy. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training 44: 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKinnon, Jacqueline M., and Leslie S. Greenberg. 2017. Vulnerable Emotional Expression in Emotion Focused Couples Therapy: Relating Interactional Processes to Outcome. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy 43: 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNulty, James K. 2011. The Dark Side of Forgiveness: The Tendency to Forgive Predicts Continued Psychological and Physical Aggression in Marriage. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 37: 770–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, Linda Ross. 2000. Forgiveness and Public Trust. Fordham Urban Law Journal 27: 1515–40. Available online: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj/vol27/iss5/33 (accessed on 1 September 2024). [CrossRef]

- Miller, Andrea J., and Everett L. Worthington, Jr. 2010. Sex Differences in Forgiveness and Mental Health in Recently Married Couples. The Journal of Positive Psychology 5: 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Andrea J., and Everett L. Worthington, Jr. 2015. Sex, Forgiveness, and Health. In Forgiveness and Health. Edited by Loren L. Toussaint, Everett L. Worthington and David R. Williams. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 173–87. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Andrea J., Everett L. Worthington, Jr., and Michael A. McDaniel. 2008. Gender and Forgiveness: A Meta-Analytic Review and Research Agenda. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 27: 843–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller-McLemore, Bonnie J. 1999. Feminist Theory in Pastoral Theology. In Feminist and Womanist Pastoral Theology. Edited by Bonnie J. Miller-McLemore and Brita L. Gill-Austern. Nashville: Abingdon Press, pp. 77–94. [Google Scholar]

- Monthly Bulletin of Interior Statistics. 2024. Number and Rates of Birth, Death, Marriage and Divorce. Ministry of the Interior, Taiwan. August 1. Available online: https://www.ris.gov.tw/app/portal/346 (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Norlock, Kathryn J. 2018. Forgiveness from a Feminist Perspective, 2nd ed. Lanham: Lexington Books. [Google Scholar]

- Okimoto, Tyler G., Michael Wenzel, and Kyli Hedrick. 2013. Refusing to Apologize Can Have Psychological Benefits (and We Issue No Mea Culpa for This Research Finding). European Journal of Social Psychology 43: 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto-Ursúa, María, Rafael Jódar, Elena Gismero-Gonzalez, María José Carrasco, María Pilar Martínez, and Virginia Cagigal. 2018. Conditional or Unconditional Forgiveness? An Instrument to Measure the Conditionality of Forgiveness. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 28: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regan, Pamela C. 2015. Infidelity. In The International Encyclopedia of Human Sexuality. Edited by Anne Bolin and Patricia Whelehan. Chichester: Wiley, pp. 583–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothwell, Jonathan. 2024. Married Americans Thriving at Higher Rates than Unmarried Adults. Gallup News. March 22. Available online: https://news.gallup.com/poll/642590/married-americans-thriving-higher-rates-unmarried-adults.aspx (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Ruether, Rosemary Radford. 2009. Feminist Theology: Where Is It Going? International Journal of Public Theology 4: 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scuka, Richard F. 2015. A Clinician’s Guide to Helping Couples Heal from the Trauma of Infidelity. Journal of Couple & Relationship Therapy 14: 141–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, Pavica, and Mary Grace Antony. 2018. Forgive and Forget: A Typology of Transgressions and Forgiveness Strategies in Married and Dating Relationships. Western Journal of Communication 83: 232–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Nick. 2008. I Was Wrong: The Meanings of Apologies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thai, Michael, Michael Wenzel, and Tyler G. Okimoto. 2023. Turning Tables: Offenders Feel Like “Victims” When Victims Withhold Forgiveness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 49: 233–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treas, Judith, and Deirdre Giesen. 2000. Sexual Infidelity among Married and Cohabitating Americans. Journal of Marriage and the Family 62: 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldron, Vincent R., and Douglas L. Kelley. 2005. Forgiving Communication as a Response to Relational Transgressions. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 22: 723–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Hui-Chi. 2014. A Study of Forgiveness of Extramarital Affairs: The Perspective of Wives. NTU Social Work Review 30: 91–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witvliet, Charlotte vanOyen, Lindsey M. Root Luna, Jill L. VanderStoep, Trechaun Gonzalez, and Gerald D. Griffin. 2019. Granting Forgiveness: State and Trait Evidence for Genetic and Gender Indirect Effects through Empathy. The Journal of Positive Psychology 15: 390–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodyatt, Lydia, Michael Wenzel, Tyler G. Okimoto, and Michael Thai. 2022. Interpersonal Transgressions and Psychological Loss: Understanding Moral Repair as Dyadic, Reciprocal, and Interactionist. Current Opinion in Psychology 44: 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worthington, Everett L., Jr., and Michael Scherer. 2004. Forgiveness Is an Emotion-Focused Coping Strategy That Can Reduce Health Risks and Promote Health Resilience: Theory, Review, and Hypotheses. Psychology & Health 19: 385–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worthington, Everett L., Jr. 2003. Forgiving and Reconciling: Bridges to Wholeness and Hope. Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Worthington, Everett L., Jr. 2005. More Questions about Forgiveness: Research Agenda for 2005–2015. In Handbook of Forgiveness. Edited by Everett L. Worthington, Jr. New York: Brunner Routledge, pp. 557–74. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Hui-Lin, Huan-Yi Lin, and Yu-Cheng Kuo. 2012. A Study on the Trends, Impacts, and Responses to the Development of the Divorce Rate in Our Country. Report Commissioned by the Ministry of the Interior to the Chung-Hua Institution for Economic Research, December. Available online: https://www.ris.gov.tw/documents/data/8/6/22653ac2-4c33-40b7-9f38-45403abe1334.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Yu, Te-Hui. 1992. The Chinese Perspective on Happiness: Tranquility and Open-Mindedness. Taichung: Living Psychology Publishers Co. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Michelle Xue, and Marius van Dijke. 2020. Expressing Forgiveness after Interpersonal Mistreatment: Power and Status of Forgivers Influence Transgressors’ Relationship Restoration Efforts. Journal of Organizational Behavior 41: 782–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Guan-Yu. 2021. Taiwan Tops Asia in Registration Rates for Extramarital Affair Websites, with over 80% Believing Affairs Help “Self-Healing”. Mirror Life. March 22. Available online: https://www.mirrormedia.mg/story/20210322web009 (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Zuccarini, Dino, Susan M. Johnson, Tracy L. Dalgleish, and Judy A. Makinen. 2013. Forgiveness and Reconciliation in Emotionally Focused Therapy for Couples: The Client Change Process and Therapist Interventions. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy 39: 148–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).