Use of Space and Safety Perceptions from a Gender Perspective: University Campus, Student Lodging, and Leisure Spots in Concepción (Chile)

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Student Geographies and Gender Focus

1.2. Fear of Crime from a Gender Perspective

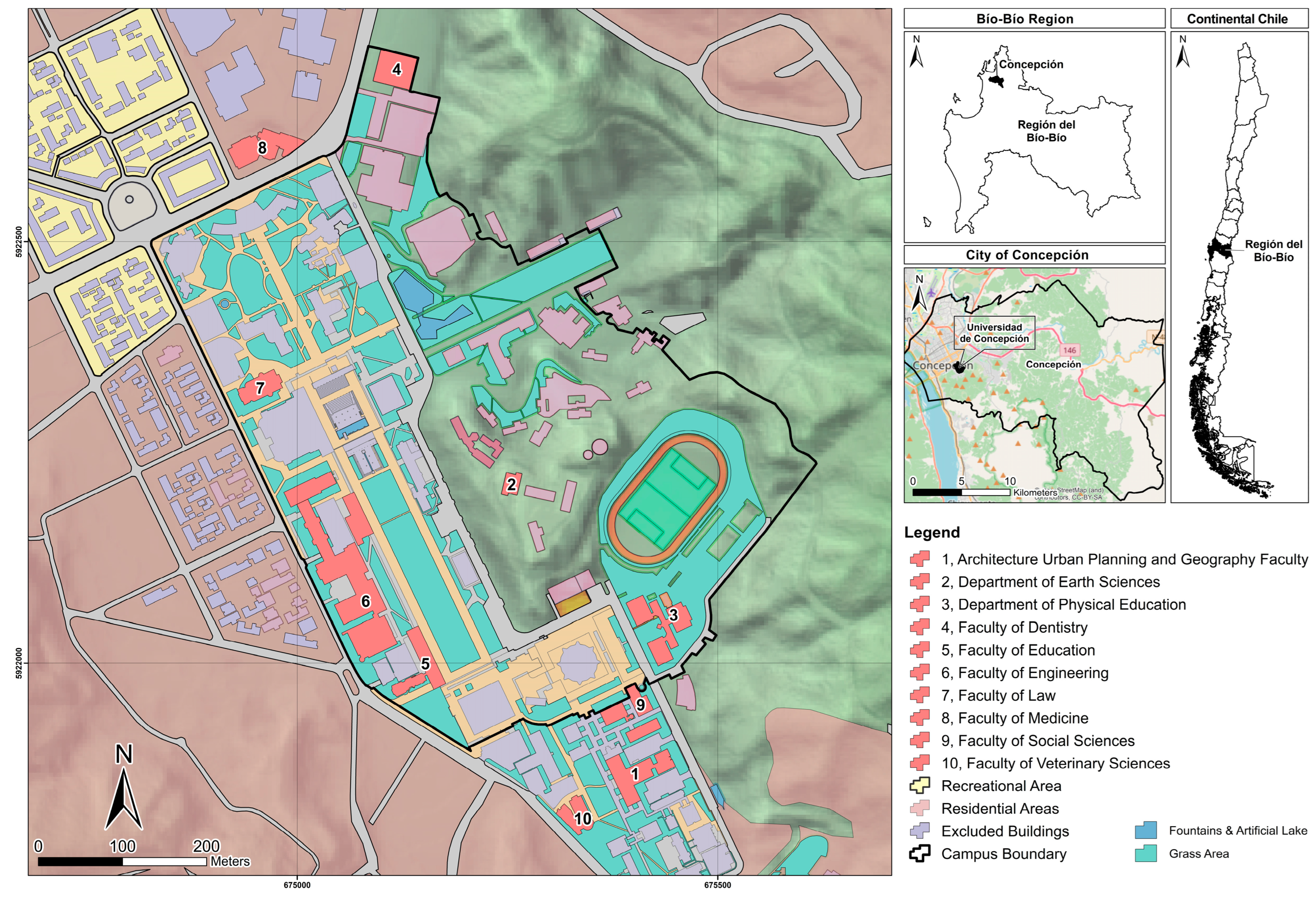

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Housing Safety and Social Construction

2G, female university student, 23 years old: [I’m glad that the place has] a front door concierge, good lighting, and transportation which can leave me near the apartment, so I don’t have to walk so much and risk myself. I think the neighbors are important too.

9J, female university student, 29 years old: First, the gate needs to stay closed. Or else, if it’s in a condo complex, where there’s a space where you can have more control over who can come nearby. That, more than anything.

4L, male university student, 21 years old: The location, being in a neighborhood that’s considered safe, more than anything else I go by what people say […] For example, near the university I feel safer, because I know that there are always students, and that most of the population is young. Things like that. By contrast, in a place that’s too far away which I don’t really know and where the streets are too deserted, I feel less secure there.

3.2. University Campus and Security Perceptions

9J, female university student, 29 years old: In the morning, when I have to come in (to university) earlier, I ask my partner to bring me to the stop, because when it’s really late or really early in the morning, it’s very dangerous.

8D, female university student, 23 years old: The most dangerous ones are, of course, the ones that are furthest out, like going to the waterfall, because out there you have less security, like fewer guards. […] Generally, the more open spaces. For example, in Los Patos lake, I feel like over there, sometimes there’s some dangerous situations. […] there aren’t many guards and there aren’t any buildings with lots of people around, like the faculties.

10J, female university student, 21 years old: I try to avoid walking alone so late on the street, so the earlier the better. I dunno, not taking my cell phone out on the street, to avoid those things. [Saying where I am] with my friends and my boyfriend.

3.3. Leisure Spaces and Security Perceptions

5M, male university student, 20 years old: [Leisure spaces should have some] type of guard. I think that the influence is that I can feel safer, but I usually don’t think a lot about that because I don’t go around thinking that something bad’s going to happen to me.

3A, female university student, 22 years old: Yes, totally [being a woman has an impact]. Because you know that something can happen to you, or someone’s going to have, you know, could have bad intentions with you. And well, particularly people that you don’t know. You’re predisposed to avoid doing things or unwinding so much in places where you don’t feel safe. […] They [men] go like, with a role that they have to look after their female friends, or at least people, the men I’ve spent time with, have taken care of that. So they also assume that something could happen to us women.

19F, female university student, 21 years old: I share my location with my mom who’s in San Carlos, but that’s still good. I send a message to my friends like ‘I’m in’ or ‘I’m here’. Or ‘come and get me together’ or stuff like that. There’s pepper spray too, especially.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ackermann, Anton, and Gustav Visser. 2016. Studentification in Bloemfontein, South Africa. Bulletin of Geography. Socio-Economic Series 31: 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamel, Alexis. 2021. The Magnitude of ‘All-Inclusive Energy Packages’ in the UK Student Housing Sector. Area 53: 464–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allinson, John. 2006. Over-Educated, Over-Exuberant and Over Here? The Impact of Students on Cities. Planning Practice & Research 21: 79–94. [Google Scholar]

- Beebeejaun, Yasminah. 2017. Gender, Urban Space, and the Right to Everyday Life. Journal of Urban Affairs 39: 323–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondi, Liz. 1998. Gender, Class, and Urban Space: Public and Private Space in Contemporary Urban Landscapes. Urban Geography 19: 160–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, Kathy, and Linda Liska Belgrave. 2015. Grounded Theory. In The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology. Edited by George Ritzer. Hoboken: Wiley, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Day, Kristen. 1994. Conceptualizing Women’s Fear of Sexual Assault on Campus: A Review of Causes and Recommendations for Change. Environment and Behavior 26: 742–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, Kristen. 1999. Strangers in the Night: Women’s Fear of Sexual Assault on Urban College Campuses. Journal of Architectural and Planning Research 16: 289–312. [Google Scholar]

- Day, Kristen. 2001. Constructing Masculinity and Women’s Fear in Public Space in Irvine, California. Gender, Place and Culture: A Journal of Feminist Geography 8: 109–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deere, Carmen Diana, Gina E. Alvarado, and Jennifer Twyman. 2012. Gender Inequality in Asset Ownership in Latin America: Female Owners vs. Household Heads. Development and Change 43: 505–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyhouse, Carol. 2006. Students: A Gendered History. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, Bonnie S., Francis T. Cullen, and Michael G. Turner. 2000. The Sexual Victimization of College Women. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice. [Google Scholar]

- García-Carpintero, María, Rocío de Diego-Cordero, Lorena Pavón-Benítez, and Lorena Tarriño-Concejero. 2022. ‘Fear of Walking Home Alone’: Urban Spaces of Fear in Youth Nightlife. European Journal of Women’s Studies 29: 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gbadegesin, Job Taiwo, Markson Opeyemi Komolafe, Taiwo Frances Gbadegesin, and Kehinde O. Omotoso. 2021. Off-Campus Student Housing Satisfaction Indicators and the Drivers: From Student Perspectives to Policy Re-Awakening in Governance. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment 31: 889–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, David. 2000. Spaces of Hope. Berkeley: California University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haskell, Lori, and Melanie Randall. 1998. The Politics of Women’s Safety: Sexual Violence, Women’s Fear and the Public/Private Split [The Women’s Safety Project]. Resources for Feminist Research 26: 113–49. [Google Scholar]

- Holton, Mark. 2016. The Geographies of UK University Halls of Residence: Examining Students’ Embodiment of Social Capital. Children’s Geographies 14: 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holton, Mark, and Kirsty Finn. 2018. Being-in-Motion: The Everyday (Gendered and Classed) Embodied Mobilities for UK University Students Who Commute. Mobilities 13: 426–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holton, Mark, and Mark Riley. 2013. Student Geographies: Exploring the Diverse Geographies of Students and Higher Education: Student Geographies. Geography Compass 7: 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbard, Phil. 2013. Carnage! Coming to a Town Near You? Nightlife, Uncivilised Behaviour and the Carnivalesque Body. Leisure Studies 32: 265–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeckel, Monika, and Marieke Van Geldermalsen. 2006. Gender Equality and Urban Development: Building Better Communities for All. Global Urban Development 2: 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Keane, Carl. 1998. Evaluating the Influence of Fear of Crime as an Environmental Mobility Restrictor on Women’s Routine Activities. Environment and Behavior 30: 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, Nigel, and Christine Horrocks. 2009. Interviews in Qualitative Research. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Koskela, Hille. 1997. ‘Bold walk and breakings’: Women’s spatial confidence versus fear of violence. Gender, Place and Culture: A Journal of Feminist Geography 4: 301–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larreche, José, and Lucía Cobo. 2021. Urbanismo de Implicación Feminista. El Derecho al Territorio. Bitácora Urbano Territorial 31: 101–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Listerborn, Carina. 2016. Feminist Struggle Over Urban Safety and the Politics of Space. European Journal of Women’s Studies 23: 251–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugones, María. 2008. Colonialidad y género. Tabula Rasa 9: 73–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, Doreen. 1994. Space, Place and Gender. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- McDowell, Linda. 1983. Towards an Understanding of the Gender Division of Urban Space. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 1: 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mingo, Araceli. 2010. Ojos que no ven…Violencia escolar y género. Perfiles Educativos 32: 25–48. [Google Scholar]

- Monro, Surya. 2005. Beyond Male and Female: Poststructuralism and the Spectrum of Gender. International Journal of Transgenderism 8: 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss, Dorothy, and Ingrid Richter. 2010. Understanding Young People’s Transitions in University Halls Through Space and Time. Young 18: 157–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murzyn-Kupisz, Monika, and Magdalena Szmytkowska. 2015. Studentification in the Postsocialist Context: The Case of Cracow and the Tri-City (Gdansk, Gdynia and Sopot). Geografie 120: 188–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pain, Rachel. 1991. Space, Sexual Violence and Social Control: Integrating Geographical and Feminist Analyses of Women’s Fear of Crime. Progress in Human Geography 15: 415–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pain, Rachel. 2001. Gender, Race, Age and Fear in the City. Urban Studies 38: 899–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecheny, Mario Martin, and Rafael De la Dehesa. 2014. Sexuality and politics in Latin America: An outline for discussion. In Sexuality and Politics: Regional Dialogues from the Global South. Edited by Sonia Corrêa, Rafael De la Dehesa and Richard Guy Parker. Rio de Janeiro: Sexuality Policy Watch, pp. 96–135. [Google Scholar]

- Phipps, Alison. 2018. ‘Lad Culture’ and Sexual Violence Against Students. In Gender Based Violence in University Communities. Edited by Anita Sundary and Ruth Lewis. Bristol: Policy Press, pp. 41–60. [Google Scholar]

- Phipps, Alison, and Geraldine Smith. 2012. Violence Against Women Students in the UK: Time to Take Action. Gender and Education 24: 357–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prada-Trigo, José. 2019. Understanding Studentification Dynamics in Low-Income Neighbourhoods: Students as Gentrifiers in Concepción (Chile). Urban Studies 56: 2863–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, Valerie, and Ebru Ustundag. 2005. Feminist Geographies of the “City”: Multiple Voices, Multiple Meanings. In A Companion to Feminist Geography. Edited by Lise Nelson and Joni Seager. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, pp. 211–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ratnayake, Rangajeewa. 2017. Sense of Safety in Public Spaces: University Student Safety Experiences in an Australian Regional City. Rural Society 26: 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revington, Nick. 2021. Age Segregation, Intergenerationality, and Class Monopoly Rent in the Student Housing Submarket. Antipode 53: 1228–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revington, Nick. 2022. Studentification as Gendered Urban Process: Student Geographies of Housing in Waterloo, Canada. Social & Cultural Geography 25: 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, Nicola, Catherine Donovan, and Matthew Durey. 2022. Gendered Landscapes of Safety: How Women Construct and Navigate the Urban Landscape to Avoid Sexual Violence. Criminology & Criminal Justice 22: 287–303. [Google Scholar]

- Ruddick, Sue. 1996. Constructing difference in public spaces: Race, class, and gender as interlocking systems. Urban Geography 17: 132–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scraton, Sheila, and Beccy Watson. 1998. Gendered cities: Women and public leisure space in the ‘postmodern city’. Leisure Studies 17: 123–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segato, Rita Laura. 2016. La guerra contra las mujeres. Zamora: Traficantes de Sueños. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Darren. 2004. ‘Studentification’: The Gentrification Factory? In Gentrification in a Global Context: The New Urban Colonialism. Edited by Rowland Atkinson. London: Routledge, pp. 73–90. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Darren, and Louise Holt. 2007. Studentification and ‘Apprentice’ Gentrifiers Within Britain’s Provincial Towns and Cities: Extending the Meaning of Gentrification. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 39: 142–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Joan. 2005. Housing, Gender and Social Policy. In Housing and Social Policy: Contemporary Themes and Critical Perspective. Edited by Peter Somerville and Nigel Sprigings. London: Routledge, pp. 151–79. [Google Scholar]

- Soja, Edward. 2013. Seeking Spatial Justice. Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Spain, Daphne. 2014. Gender and Urban Space. Annual Review of Sociology 40: 581–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starkweather, Sarah. 2007. Gender, Perceptions of Safety and Strategic Responses Among Ohio University Students. Gender, Place & Culture 14: 355–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomisch, Elizabeth, Angela Gover, and Wesley Jennings. 2011. Examining the Role of Gender in the Prevalence of Campus Victimization, Perceptions of Fear and Risk of Crime, and the Use of Constrained Behaviors among College Students Attending a Large Urban University. Journal of Criminal Justice Education 22: 181–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tummers, Lidewij, and Wankiewicz Heidrun. 2020. Gender Mainstreaming Planning Cultures: Why ‘Engendering Planning’ Needs Critical Feminist Theory. Gender, Journal for Gender, Culture and Society 12: 11–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, Gill. 1989. The Geography of Women’s Fear. Area 21: 385–90. [Google Scholar]

- Walton-Roberts, Margaret. 2015. Femininity, Mobility and Family Fears: Indian International Student Migration and Transnational Parental Control. Journal of Cultural Geography 32: 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolnough, April. 2009. Fear of Crime on Campus: Gender Differences in Use of Self-Protective Behaviours at an Urban University. Security Journal 22: 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavuz, Nilay, and Eric Welch. 2010. Addressing Fear of Crime in Public Space: Gender Differences in Reaction to Safety Measures in Train Transit. Urban Studies 47: 2491–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Prada-Trigo, J.; Quijada, P.; Varela, G. Use of Space and Safety Perceptions from a Gender Perspective: University Campus, Student Lodging, and Leisure Spots in Concepción (Chile). Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 348. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060348

Prada-Trigo J, Quijada P, Varela G. Use of Space and Safety Perceptions from a Gender Perspective: University Campus, Student Lodging, and Leisure Spots in Concepción (Chile). Social Sciences. 2025; 14(6):348. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060348

Chicago/Turabian StylePrada-Trigo, José, Paula Quijada, and Gabriela Varela. 2025. "Use of Space and Safety Perceptions from a Gender Perspective: University Campus, Student Lodging, and Leisure Spots in Concepción (Chile)" Social Sciences 14, no. 6: 348. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060348

APA StylePrada-Trigo, J., Quijada, P., & Varela, G. (2025). Use of Space and Safety Perceptions from a Gender Perspective: University Campus, Student Lodging, and Leisure Spots in Concepción (Chile). Social Sciences, 14(6), 348. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060348