1. Introduction

Hate speech can be defined as “any form of expression intended to incite, promote, disseminate or justify violence, hatred or discrimination against a person or group of persons on the grounds of their personal characteristics or status, such as “race”, colour, language, religion, nationality, national or ethnic origin, age, disability, gender, gender identity and sexual orientation” (

Council of Europe 2022). In other words, hate speech is defined (a) as expressions of hostility directed at people; (b) justified by factors of identity or belonging (real or perceived) to social groups, gender, ethnicity, ideology, or physical appearance, among others (

Sponholz 2023;

Kansok-Dusche et al. 2023); and (c) it also seeks dissemination and publicity (

Schwertberger and Rieger 2021).

The interpretation of hate speech can be clearer or more ambiguous based on its explicit or implied content, as well as its symbolic character (

Weber et al. 2024), and its intentionality. Hate speech is intended to harm, humiliate, or belittle a person or group of people. It is also intended to be seen by an audience and incite more hatred (

Rodriguez Ramos 2022;

Brown 2018).

Currently, the Internet is the main source of hate speech (

Blaya 2019;

Paz et al. 2020). At least 75% of people who use social networks or instant messaging have witnessed or experienced insults, threats, or hate speech online (

EU Commission 2016). Hate speech occurs in two main contexts: social media (

Castaño-Pulgarin et al. 2021) and online gaming (

Costa et al. 2024). In addition, there is the “massive cyberattack”, in which a large number of users post comments directed at an individual or small group, using language intended to shame, humiliate, marginalize, or insult, in a digital bombardment that is difficult to escape (

Cover 2023).

As the authors point out, the material basis of hate speech is disinformation (

Di Fátima 2024, p. 12). Considered a communication phenomenon in the post-truth era, these discourses contribute to the promotion of an ‘informational disorder’—disinformation—that aims to cause harm (

Lilleker and Pérez-Escolar 2023;

Wardle and Derakhshan 2017;

Barrientos Rastrojo 2022), using insults, threats, and abuse to incite violence, reinforce stereotypes, and create a climate of intolerance (

Wachs and Wright 2019). The harm is compounded by the sense of security of those who perpetrate and spread hate speech through social networks, shielded by anonymity, which creates particular helplessness in victims (

Poland 2016), especially when those victims are adolescents (

Kolotouchkina et al. 2023).

Marinoni et al. (

2024a) found a positive relationship between the possibility of using a fake profile and the perpetration of cyberbullying.

According to the authors, there is a relationship between victimization and the perpetration of hate speech (

Wachs et al. 2022b). In fact,

Walrave and Heirman (

2011) found that online victimization was the most important predictor of future cyberbullying perpetration. In other words, being the recipient of hate speech is related to perpetrating, disseminating, issuing, or promoting hate speech (

Ramón Ortiz and Guizado 2023).

Musante and DeWalt (

2011) and

Pinker (

2011) argue that the most common factors driving violent behavior are revenge, power, entertainment, and ideology.

Ballaschk et al. (

2021) consider hate speech to be a form of violence.

Regarding revenge,

Kowalski and Limber (

2007) found that students exposed to cyberbullying tend to experience anger afterward (p. 2). This anger is related to the perception of being on the receiving end of an unfair situation (

Van Dorn 2018). Some adolescents respond by using hate speech as a means of revenge or to express a desire to harm the other (

Ballaschk et al. 2021).

Pinker (

2011) posits that violence is associated with the pursuit of power and the perception of exerting control over others.

Ballaschk et al. (

2021) found a correlation between the desire for power and the perpetration of hate speech.

The idea that seeking enjoyment justifies the expression of hate speech is based on two main principles. First, humor serves to minimize the severity of hate speech. Second, the content of the messages may cause recipients to view the senders as overly sensitive or lacking a sense of humor (

Jane 2015).

Tanrikulu and Erdur-Baker (

2021) found that the two main motives for adolescents to engage in hate speech were revenge and entertainment. Regarding revenge,

Kowalski and Limber (

2007) found that students exposed to cyberbullying tend to experience feelings of anger after the bullying (p. 2). Thus, a correlation would be expected between those who receive hate speech and those who perpetrate hate speech, which could be explained as reactive aggression motivated by revenge (

Fluck 2017;

Runions et al. 2018;

Tanrikulu and Erdur-Baker 2021;

Wachs and Wright 2019). Other authors also note that some youth may use hate speech as a means of revenge when they feel threatened, treated unfairly, frustrated, or angry (

Wachs et al. 2022b, p. 10). In addition,

Wachs et al. (

2022a) found that the revenge subscale of the Motivations to Engage in Hate Speech Perpetration Scale (MHATE) had the highest frequency (p. 17).

Marinoni et al. (

2024b) found that, particularly in online games, the normalization of teasing and aggressive behavior is common as part of the socialization process.

Second, we have the entertainment or fun motive. Hate speech is often expressed in the form of jokes to gain power and fit in with groups within youth peer networks (

Wachs et al. 2022a). Hate speech that is masked by intentional humor may be perceived as culturally acceptable, creating an added sense of helplessness (

Cover 2023).

Schmid et al. (

2024) identified fun and entertainment as one of the most common motives for justifying and perpetrating hate speech. The trivialization of hate speech, treated as a humorous expression, seeks to provide justification and be interpreted as less serious and even innocent (

Schmid et al. 2024). This further contributes to dehumanizing and creating helplessness in victims, while establishing moral disengagement processes or mechanisms that make it easier for perpetrators to legitimize their aggressive behavior (

Bandura 2016) and assign blame to the victim (

Álvarez-Turrado et al. 2024).

Finally, the relationship between hate speech and emotional self-control should be highlighted.

Teruel et al. (

2019, p. 2) define emotional intelligence as “the knowledge and/or competencies to manage emotions effectively in order to regulate social and emotional behaviors”. Emotional self-control is defined as the ability to control impulses when faced with ethical, moral, legal, social, or other constraints that make an impulse inappropriate or harmful (

West and Thomson 2025).

As the authors point out, adolescence is a period characterized by strong feelings and emotions (

O′Brien 2014). In this sense,

Delgado et al. (

2019) demonstrated that the likelihood of being a victim or aggressor of cyberbullying increases with the level of aggressiveness, which implies a lower capacity for emotional self-control. Self-control is based on changes in motivation that depend on one’s identity and situational context (

Berkman et al. 2017). Regarding identity, self-control exhibits both a cognitive–structural component situated in the inferior frontal gyrus and anterior insula and a socio-emotional component located in the middle frontal gyrus and posterior cingulate (

Hofmann et al. 2009;

Li et al. 2021;

Steinberg 2008). Together, these components predispose individuals to respond differently to different situations (

Baumeister et al. 2007). The manner in which thoughts and feelings (or emotions) are adapted is influenced by two factors. The first is personal preferences, and the second is social situations (

Koole 2008;

Paschke et al. 2016). There is a substantial degree of overlap between self-control and emotional self-regulation (

Musante and DeWalt 2011).

Gross and Thompson (

2007) posits that emotional self-regulation is a form of emotional self-control.

Recent studies also show that the emotional intelligence profile is a variable that can explain to a large extent the variability of cybervictimization, so those who show a higher level of emotional self-regulation have a lower risk of cybervictimization (

Villegas-Lirola 2024). At the other extreme, those who have received hate speech and have low emotional self-control would be precisely those who perpetrate the most hate speech (

Turner et al. 2022). In social dynamics, the need to seek the approval of like-minded friends (

Walther 2022) leads to the development of situations such as those described among incels, one of the main groups of the manosphere. These individuals end up in a spiral of self-pity and self-loathing, which forms the basis of the fraternal bonds within their community (

Scotto di Carlo 2023). The development of such toxic masculinity shares ideas with the authoritarian personality (

Erjavec and Kovačič 2012).

The innovation of this research is that it jointly examines (1) the relationship between experiencing hate speech and perpetrating it; (2) the influence that self-control has on this relationship; and (3) whether self-control moderates the relationship between experiencing hate speech and perpetrating it by motives such as revenge and amusement. In addition, a gender analysis of these relationships is presented.

2. Method

Our research has four aims: (1) to construct an index of emotional self-control; (2) to identify gender differences in receiving and/or perpetrating hate speech; (3) to analyze the mediating role of emotional self-control between receiving and perpetrating hate speech; and (4) to analyze the moderating role of motives of (a) revenge and (b) viewing hate speech as fun.

2.1. Participants and Instrument

Non-probability accessibility sampling was used to select the participants (

Arrogante 2022). The sample consisted of 535 boys and girls from four secondary schools in Almería (Spain). Of the total sample, 48.8% were girls (261), 46.7% were boys (250), 2.6% were non-binary (14), and the rest (10) were considered non-valid (did not respond). Students ranged in age from 12 to 19 years (M = 14.88; SD = 5.39). Eighty-nine percent (476) were in compulsory secondary education, 7.9% (42) were in bachelor’s programs, and the rest were in vocational programs (17).

All missing cases for the variables of analysis were eliminated from the statistical analysis. In total, the analysis sample consisted of 413 participants, of which 50.1% (207) were girls, 46.5% (192) were boys, and the rest (14) were non-binary. The mean age was 14.47 years (SD = 1.53). The non-response rate was 22.8%, which allows us to consider the survey to be of good quality (

Biemer and Lyberg 2003).

2.2. Procedure

For data collection, four secondary schools were contacted and provided with information about the project and the questionnaire to be administered to the students. Each school agreed to participate in the project through its school council, and consent was obtained from the students’ legal custodians. Interviewers were informed of the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki regarding confidentiality, anonymity, and voluntary participation. The questionnaire was completed by the students during school hours in their regular classroom (March to June 2024). They completed it on laptops or tablets accessed via a QR code, and it took approximately thirty minutes to complete.

2.3. Data Analysis

(1) Variables

The dependent variable used was perpetrated hate speech, based on the question “In the past 12 months, how often have you experienced perpetrated hate speech at your school?”, with three response options: (1) never; (2) once or twice in the same month; (3) three times a month; (4) about once a week; (5) several times a week. The variable “perpetrated hate speech (PerpDO)” was created as a dichotomous variable (1: yes perpetrated hate speech; 0: no perpetrated hate speech).

The independent variable was having been confronted with hate speech (1: yes; 0: no). The mediating variable (emotional self-control index) was constructed from four items. The question in the questionnaire was as follows:

“All people are different. We would like to know to what extent you agree with the following statements:

L1. I think about how I feel, about my emotions.

L2. I can control my behavior.

L3. I feel responsible for my behavior.

L4. I care about how others feel”.

The motives that participants used to justify hate speech were revenge (J1) and fun (J2). Responses were recorded on a Likert scale from 1 to 5, with 1 being strongly disagree and 5 being strongly agree.

J1. It is okay to send hateful or degrading messages to someone on the Internet if they attack you, your friends, or your family first.

J2. It is okay to send hateful or degrading messages against someone on the Internet because hate speech is fun.

The gender variable (S1) refers to an individual’s self-identification as male, female, or non-binary.

(2) Construction of the Emotional Self-Control Index

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was performed on items L1, L2, L3, and L4 using the SPSS dimension reduction function (v. 29) [Analysis > Dimension Reduction > Factor]. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test of sampling adequacy and Barlett’s test of sphericity were performed, as well as Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s w-value. The maximum likelihood method was used and a scatterplot was generated. A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was then performed to verify its construct validity (Amos, v. 28). The interpretation was supported by the utility of

Gaskin and Lim (

2016). As cutoff criteria, those proposed by

Hu and Bentler (

1999) were used (

Table 1).

Once it was verified that the four items allowed the formation of a self-control index with good reliability and validity, it was categorized, taking into account the percentile distribution. This was done using the visual grouping utility (SPSS) [Transform > Visual Grouping], with four cut-off points (20% per group). This resulted in five groups (very high, high, medium, low, medium, low, and very low).

(3) Identifying gender differences

Descriptive data were calculated for the different variables, as well as percentages for the different profiles resulting from suffering/perpetrating hate speech. Four mean difference analyses were conducted using one-factor ANOVA with gender (boy, girl, non-binary) as the comparison variable and the following as the dependent variable:

(a) Receiving hate speech;

(b) Perpetrating hate speech;

(c) Justifying hate speech as funny;

(d) Believing that it is legitimate to engage in hate speech out of revenge.

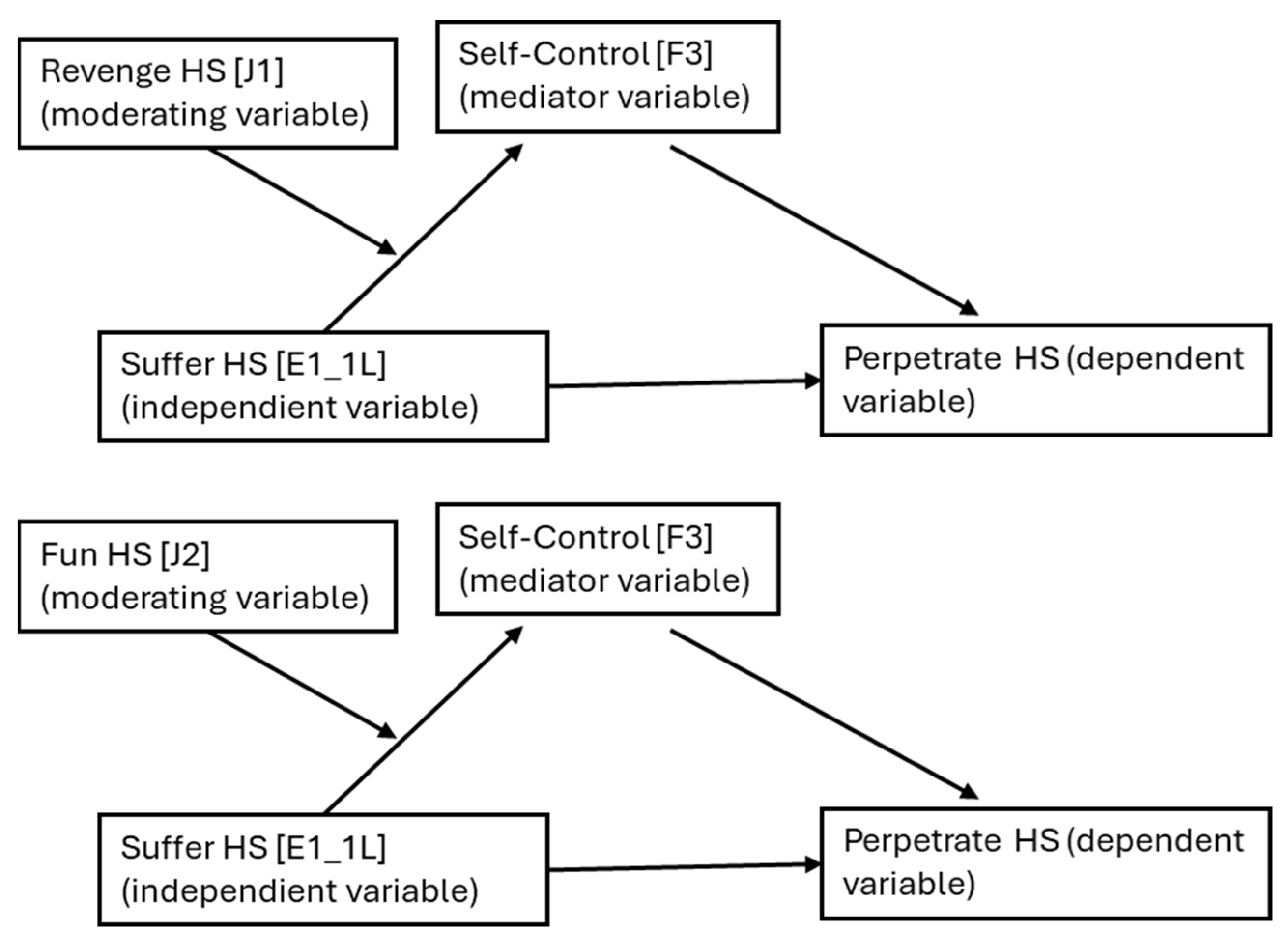

(4) Analysis of the mediating role of emotional self-control and the moderating role of (a) revenge motives and (b) viewing hate speech as humorous motives in the relationship between receiving hate speech and perpetrating hate speech.

It was based on model 7 (moderated mediation) of the PROCESS macro for SPSS (

Hayes 2013). We took perpetrating hate speech (PerpDO) as the dependent variable (Y), receiving hate speech (E1_1L) as the independent variable (X), the emotional self-control index as the mediating variable (M), and the motivation for revenge and then the motivation to consider hate speech as humorous as the moderating variable (W) first (

Figure 1).

3. Results

3.1. Construction of the Emotional Self-Control Index

As a result of the KMO test, a value of 0.684 was obtained, indicating that the correlations between pairs of variables can be explained by the rest of the variables. Barlett’s test of sphericity (chi-square: 244.97; df: 6) had a p-value of less than 0.001, which means that the variables are related to each other, thus making it possible to proceed with the exploratory factor analysis. A Cronbach’s alpha of 0.66 [CI95%: 0.58, 0.72] and a McDonald’s omega of 0.662 [CI95%: 0.58, 0.72] were obtained.

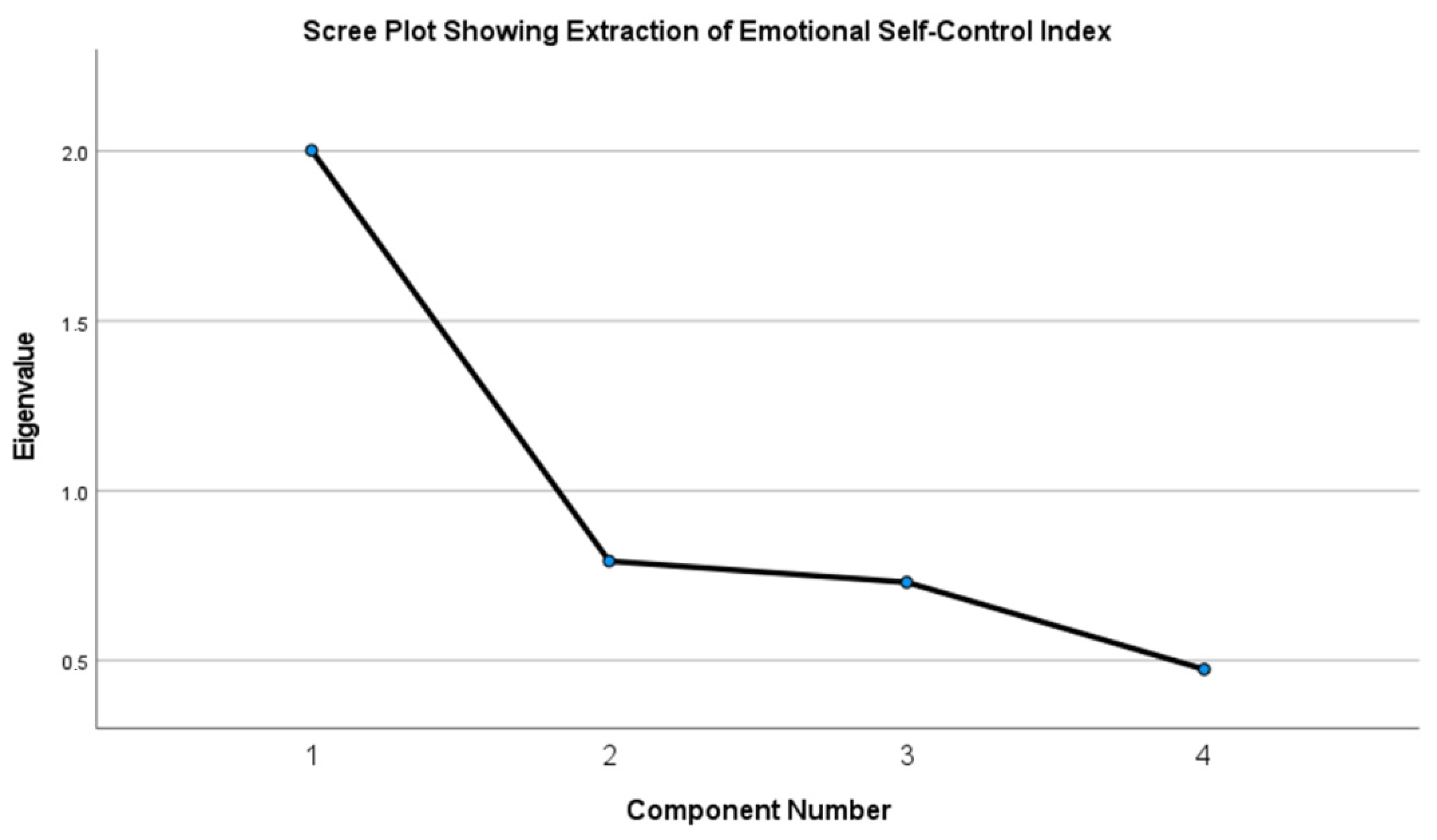

When drop contrast was used as the decision criterion (

Figure 2), the optimal number of factors was found to be 2, with the model explaining 69.88% of the variance.

A percentile scale of the Emotional Self-Control Index was constructed. If the sum of items L1, L2, L3, and L4 is less than 12, it is considered very low emotional self-control; scores between 13 and 15 are considered moderately low; between 17 and 18, moderately high; and more than 19, very high (

Table 2).

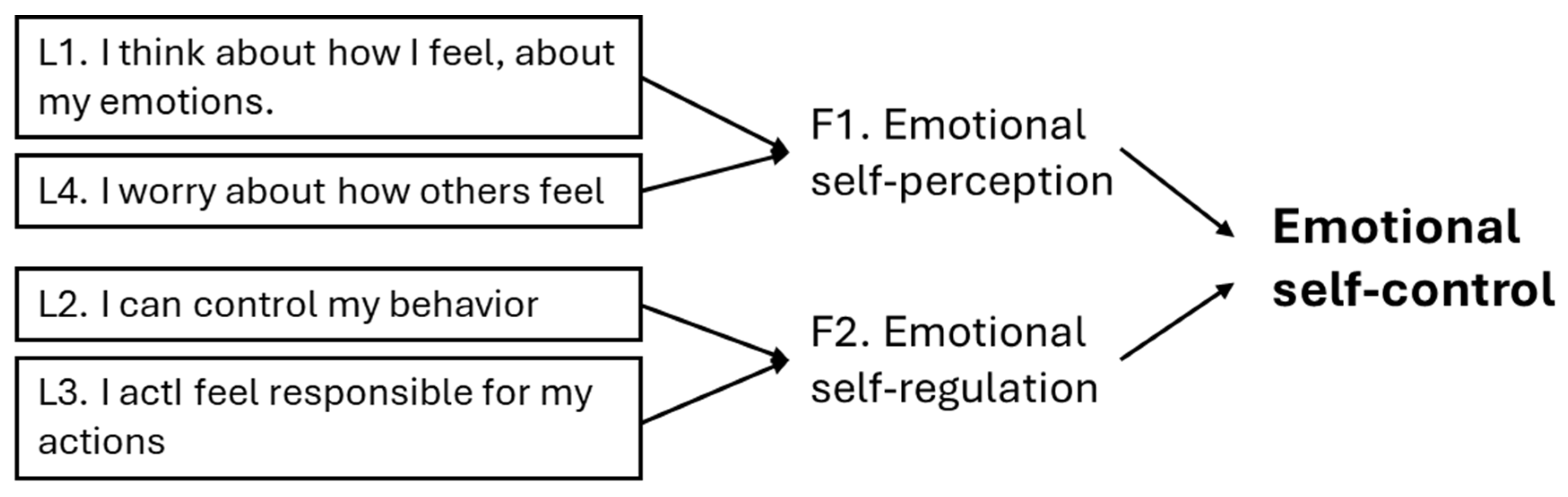

The theoretical model (

Figure 3), to be verified by Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) (

Figure 4), grouped items L1 and L4 under the Emotional Self-perception factor (F1), and items L2 and L3 under the Emotional Self-regulation factor (F2).

In terms of model fit, the various indices were rated as excellent (

Table 3).

3.2. Identification of Gender Differences

Receiving hate speech

For the variable receiving hate speech, the means and standard deviations were very similar for boys [mean: 0.31 (CI95%: 0.25; 0.38), SD: 0.46] and girls [mean: 0.29 (CI95%: 0.22; 0.35), SD: 0.45]. For the non-binary category, the mean was higher than for the other two categories [mean: 0.50 (CI95%: 0.20; 0.80), SD: 0.52]. The small number of cases for this category (14) is noteworthy.

The sample size analysis showed that the study has 80% power to detect the effect size in the process of identifying differences between groups, which is likely to lead to a slight underestimation of the effect size for the values of the group of subjects who identify as non-binary.

In the homogeneity of variances tests, a

p-value of Levene’s statistic > 0.05 was obtained assuming the null hypothesis (homogeneity of variances), using the ANOVA F test and Tuckey’s test for post hoc analysis as the reference for the analysis. The ANOVA F value was not significant (

p-value = 0.230) because it was greater than 0.05 (

Table 4).

Perpetrating Hate Speech

For the perpetrating hate speech variable, the means and standard deviations were also very similar for boys [mean: 0.58 (CI95%: 0.51; 0.65), SD: 0.50] and girls [mean: 0.55 (CI95%: 0.48; 0.61), SD: 0.50]. For the non-binary category, the mean was higher than for the other two categories [mean: 0.71 (CI95%: 0.44; 0.98), SD: 0.47].

In tests for homogeneity of variances, a p-value of Levene’s statistic < 0.05 was obtained, leading to the assumption of the alternative hypothesis (no homogeneity of variances). Therefore, Welch’s test and the Games–Howel test were used for post hoc analysis.

The

p-value of Welch’s statistic was not significant (

p-value = 0.412 > 0.05). The difference between the means was not significant for any of the groups (

Table 5).

Perpetrating hate speech is fun

For the variable perpetrating hate speech is fun (J2), the means and standard deviations were as follows: for boys [mean: 1.77 (CI95%: 1.60; 1.94), SD: 1.19] and for girls [mean: 1.34 (CI95%: 1.22; 1.47), SD: 0.89). For the non-binary category, the mean was higher than for the other two categories [mean: 2.79 (CI95%: 1.48; 1.70), SD: 1.11].

In the homogeneity of variances tests, a p-value of Levene’s statistic < 0.05 was obtained, leading to the assumption of the alternative hypothesis (no homogeneity of variances). Therefore, Welch’s test and Games–Howel test were used for post hoc analysis.

The

p-value of Welch’s statistic was significant (

p-value < 0.001). The mean difference was significant (

Table 6).

Revenge justification for perpetration of hate speech

When asked whether it is justified to commit hate speech if we are attacked first (revenge), the means and standard deviations were very similar for boys [mean: 2.69 (CI95%: 2.47; 2.90), SD: 1.50], girls [mean: 2.49 (CI95%: 2.28; 2.70), SD: 1.51], and those who identified as non-binary [mean: 3.00 (CI95%: 2.07; 3.93), SD: 1.62].

In the homogeneity of variances tests, a p-value of Levene’s statistic > 0.05 was obtained, leading to the assumption of the null hypothesis (homogeneity of variances). Therefore, the ANOVA F test and Tuckey’s test were used for post hoc analysis.

The ANOVA F-value was not significant (

p-value = 0.253) (

Table 7).

Emotional Self-Control

For emotional self-control, the means and standard deviations were similar for boys [mean: 15.23 (CI95%: 14.75; 15.71), SD: 3.35] and girls [mean: 15.54 (CI95%: 15.13; 15.95), SD: 2.99], and slightly lower for the non-binary category [mean: 12.21 (CI95%: 9.90; 14.52), SD: 4.00].

In tests for homogeneity of variances, a p-value of Levene’s statistic > 0.05 was obtained, leading to the assumption of homogeneity of variances.

The ANOVA F value was significant (

p-value < 0.001), with a small effect [(eta-squared of 0.034 (CI95%: 0.006; 0.072)] (

Table 8).

Comparison of hate speech profiles by gender

The non-binary group is very small, making comparisons difficult. Among non-victims and non-perpetrators, girls (36.7%) show a higher percentage than boys (29.2%). Among those who are not victims but are perpetrators of hate speech, the situation is very similar (39.6% for boys and 34.8% for girls), as well as among those who are both victims and perpetrators (18.2% for boys and 19.8% for girls). On the contrary, boys are more likely than girls to be victims and non-perpetrators of hate speech (boys: 13.0%, girls: 8.7%) (

Table 9).

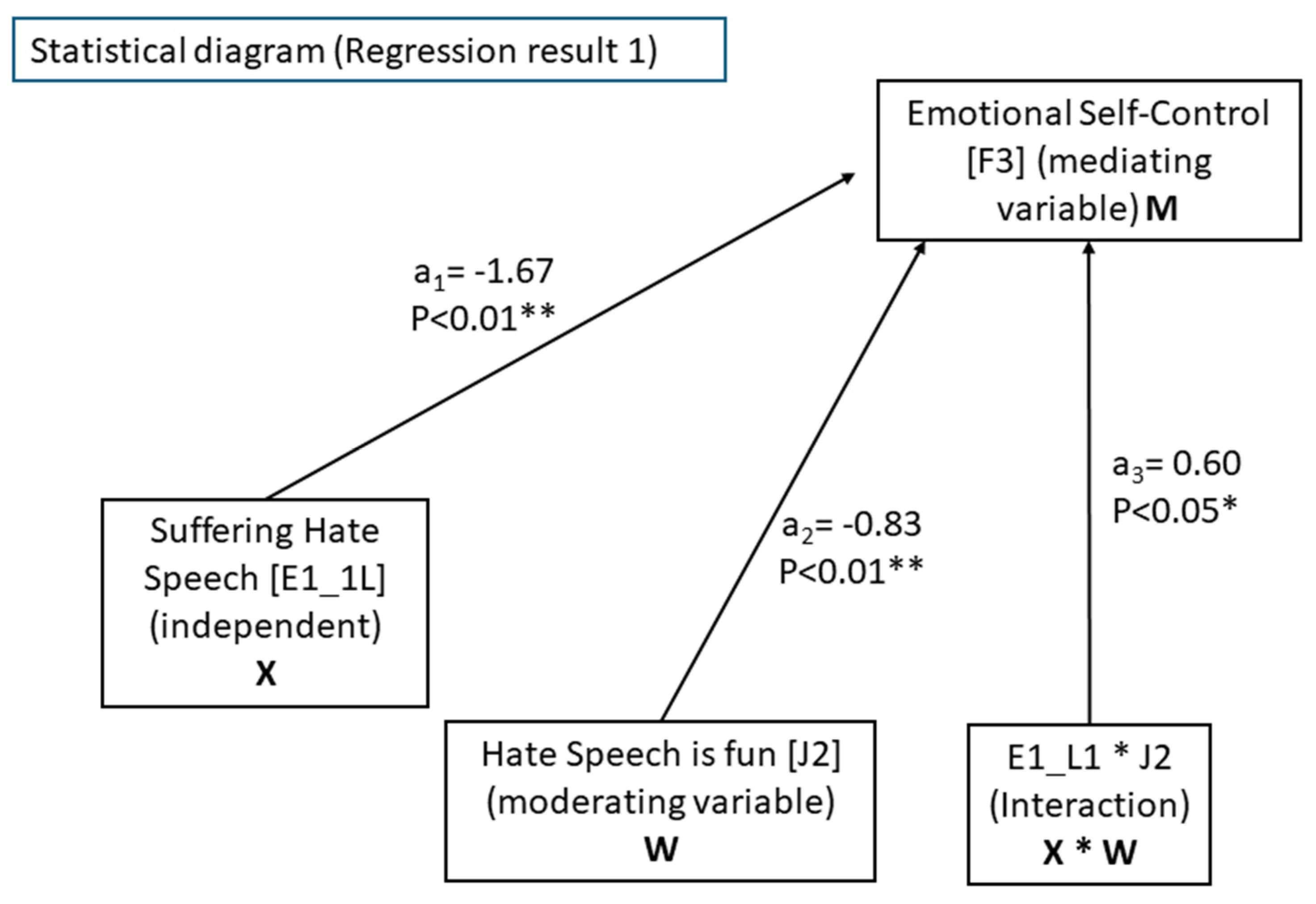

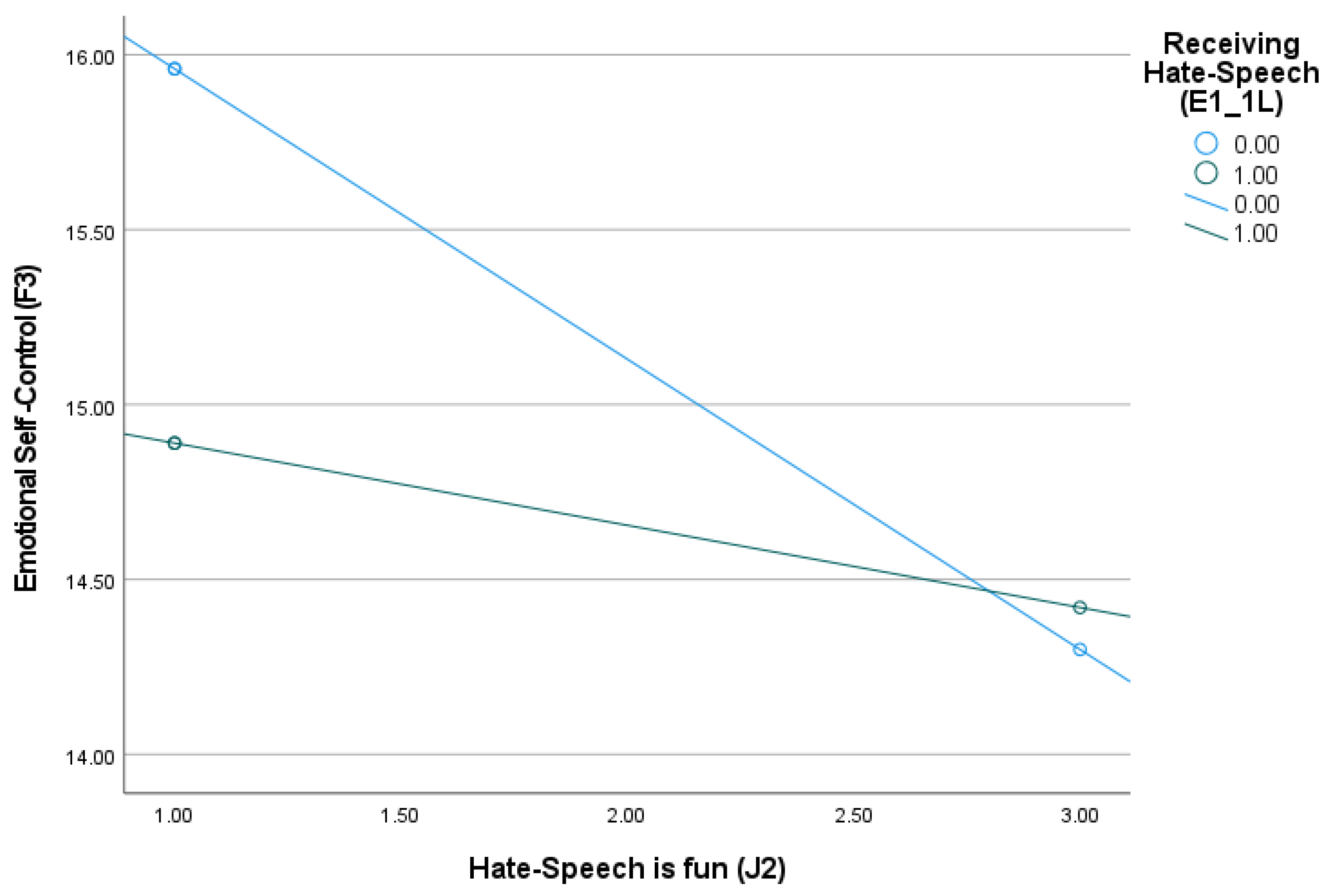

3.3. Moderated Mediation Analysis

Taking the mediating variable (Emotional Self-Control Index) as the dependent variable, suffering hate speech as the independent variable, and considering hate speech as funny as the moderating variable, we found a significant relationship between the different variables (

Figure 5).

The regression analysis between the mediating variable and the dependent variable was significant, while the relationship between receiving hate speech and perpetrating hate speech (excluding the effects of the mediating variable) was not significant (

Figure 6).

4. Discussion

Our results indicate that receiving hate speech does not imply perpetrating hate speech (c’ = 0.40,

p-value > 0.05—not significant). This result contrasts with the findings of

Wachs et al. (

2022a) and

Walrave and Heirman (

2011). However, the two variables (receiving and perpetrating hate speech) are related, as receiving and perpetrating hate speech occur significantly when low levels of self-control are present for both boys and girls. The relationship between receiving hate speech and perpetrating hate speech is determined by the presence of low levels of emotional self-regulation.

One of the goals of this work was to construct an index of emotional self-control that would allow us to know its role in the relationship between receiving and perpetrating hate speech. A two-factor structure was found, with a good internal consistency (0.66) and an accumulated variance of 69.88%. The results of the confirmatory factor analysis demonstrated excellent validity of the instrument (

Gaskin and Lim 2016).

The moderated mediation analysis showed that the variable of emotional self-control is necessary to explain the relationship between receiving hate speech and perpetrating it. It resulted in a full mediation (

Hayes 2013) (

Figure 7).

In this regard, our analysis confirms the results obtained by

Villegas-Lirola (

2024) regarding cybervictimization and by

Turner et al. (

2022) regarding self-control in the exposure and sharing of hate content online by adolescents.

However, the motive of fun turned out to be significant as a moderating variable in our sample. Regarding the perception of hate speech as fun, the analysis of the moderating effect (indirect effect conditional) showed us that boys who do not perceive hate speech as fun are not more likely to perpetrate speech hate, even when they are recipients of hate speech (effect: 0.08 (CI95%: 0.01, 0.19). Thus, among boys, not finding hate speech funny is a protective factor against its dissemination (

Figure 8).

Regarding the analysis of gender differences, no significant differences were found in terms of receiving and/or perpetrating hate speech, nor in the motivation to justify hate speech as revenge. Significant differences were found in the perception of hate speech as fun (

Marinoni et al. 2024b) and in the scores obtained for the emotional self-control index. Therefore, we can say that, in the case of boys, perpetrating hate speech is mediated by low self-control and moderated by the consideration that hate speech is fun. In the case of girls, the variable emotional self-control significantly mediates the relationship between receiving and perpetrating hate speech, but we do not find that the variable fun moderates the likelihood of perpetrating hate speech.

It is conceivable that, in the case of boys, perpetrating hate speech is related to the need to seek approval from like-minded friends (

Walther 2022) or the search for fraternal bonds from their gender community (

Scotto di Carlo 2023).

In conclusion, (1) the relationship between receiving hate speech and perpetrating hate speech was not significant, but when the emotional self-regulation variable was added, the indirect effects were significant. A situation of total mediation was found; (2) although the revenge variable was a widespread justification for perpetrating hate speech, its moderating role between receiving hate speech and perpetrating it was not significant; and (3) for the variable considering hate speech as funny, it was found to have a significant moderating role in this relationship. This was particularly true in the case of boys, given that girls do not tend to consider hate speech as funny.

5. Limitations

The main limitation of this study is that the sample belongs to a very specific region of Spain and is relatively small, so although the results can be considered for other contexts (hate speech is generalized in all countries of the world), it would be convenient to conduct cross-cultural studies to compare the results with other cultures, lifestyles, or political regimes. Furthermore, this study was conducted at one point in time, so the results of emotional self-control mediation should be considered as associations, which requires longitudinal studies that allow for causal explanations.

Another limitation of this study is the difficulty in understanding the girls’ hate speech. Although they share the fact that receiving and perpetrating hate speech is mediated by emotional self-control, motives of revenge or fun do not significantly moderate this relationship. In this sense, it should be noted that we need new studies to help us better understand the relationship between receiving and perpetrating hate speech in the case of girls.

However, despite its limitations, this work provides evidence for an intervention to address hate speech among adolescents that may help reduce its prevalence. Improving adolescents’ emotional self-control can help prevent them from engaging in hate speech, even if they receive it. In the case of adolescents, it is necessary to promote the idea that those who perpetrate hate speech must accept their responsibility and not excuse themselves with the supposedly playful nature of their aggression—because hate speech is not fun.