A Collaborative Response to Addressing Family Violence with Racialized and Diverse Communities During Pandemic Recovery in Peel Region

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Theoretical Frameworks

2.2. Community Advisory Board and Peer Research Assistant Engagement

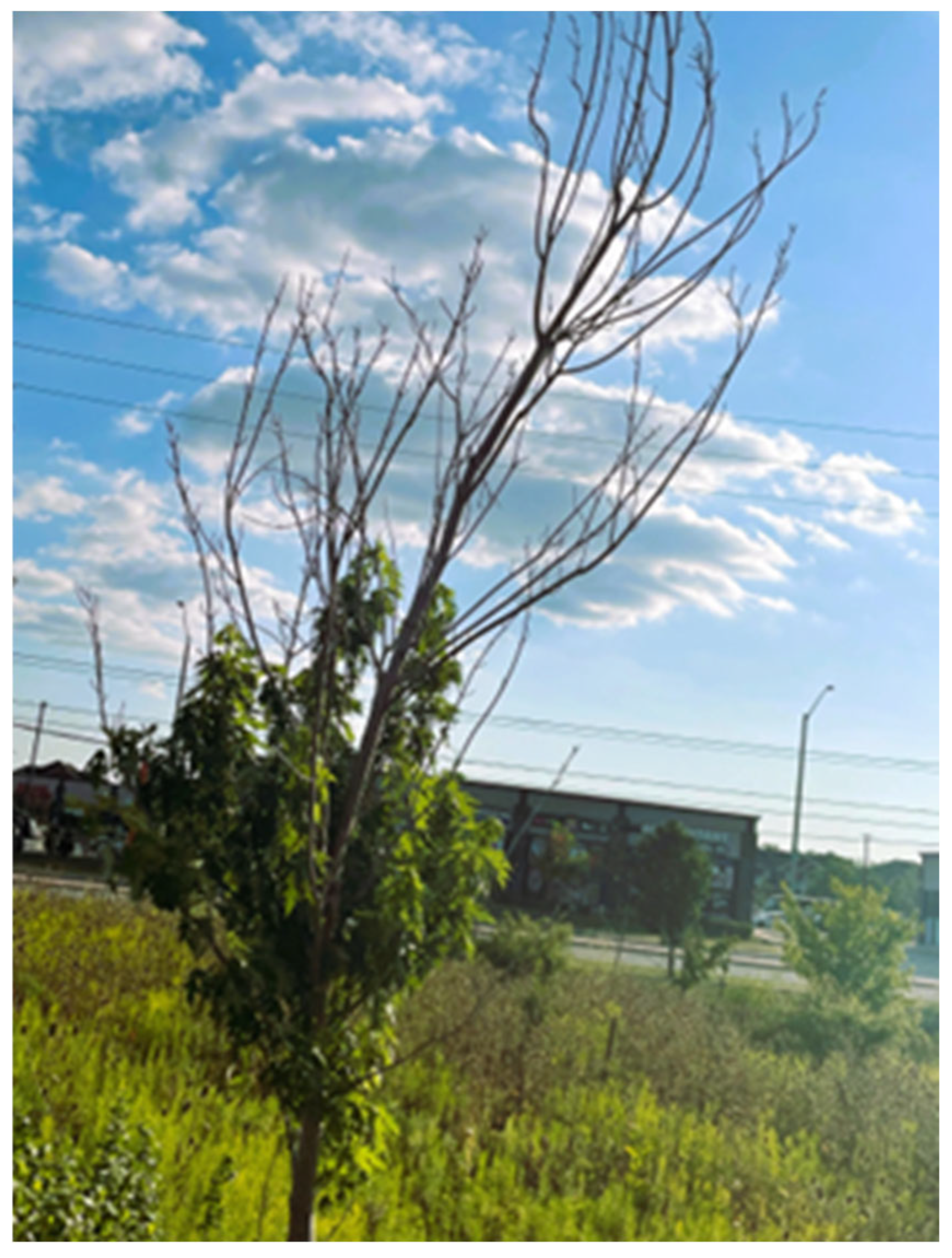

2.3. Photovoice Workshops and Their Co-Design

2.4. Recruitment of Photovoice Participants

2.5. Photovoice Workshop Process and Structure

2.6. Photovoice Data Analysis

2.7. Knowledge Translation Event and Mini Hackathon (KTE)

2.8. 25/10 Crowdsourcing and Mini Hackathon

3. Results

3.1. Photovoice Workshops

3.1.1. South Asian Women’s Group

“My child used to see us fight during COVID and I couldn’t leave then; and now that we have finally left, there is no housing, and we have moved 3 times in 1 year”(participant quote, 26 August 2023)

“I had to leave my well-paying PSW job for my child because daycares start at 7:30 a.m. and my job started at 7:00 a.m. Thus, I couldn’t do afternoons, I couldn’t do nights”(participant quote, 17 August 2023)

“I don’t know what a shelter is, what kind of environment it will have and how will it impact my kids”(participant quote, 17 August 2023)

“When all doors closed, and hands became empty, I went looking for my piece of the sky”(participant quote, 26 August 2023)

“At the end of the day you have to do it by yourself, but just the feeling that there are people to support you, can really impact you”(participant quote, 17 August 2023)

“Every woman should learn to be independent. It is my wish that every woman out there can earn her living, as it has a liberating effect. When you can support yourself, you feel more confident and do not have to feel indebted to anyone. Do not be afraid to burn bridges when necessary.”(participant quote, 26 August 2023)

“The wheel is like a circle of life, we push through it, work hard to keep it moving and sometimes it brings you back to ground zero”(participant quote, 26 August 2023)

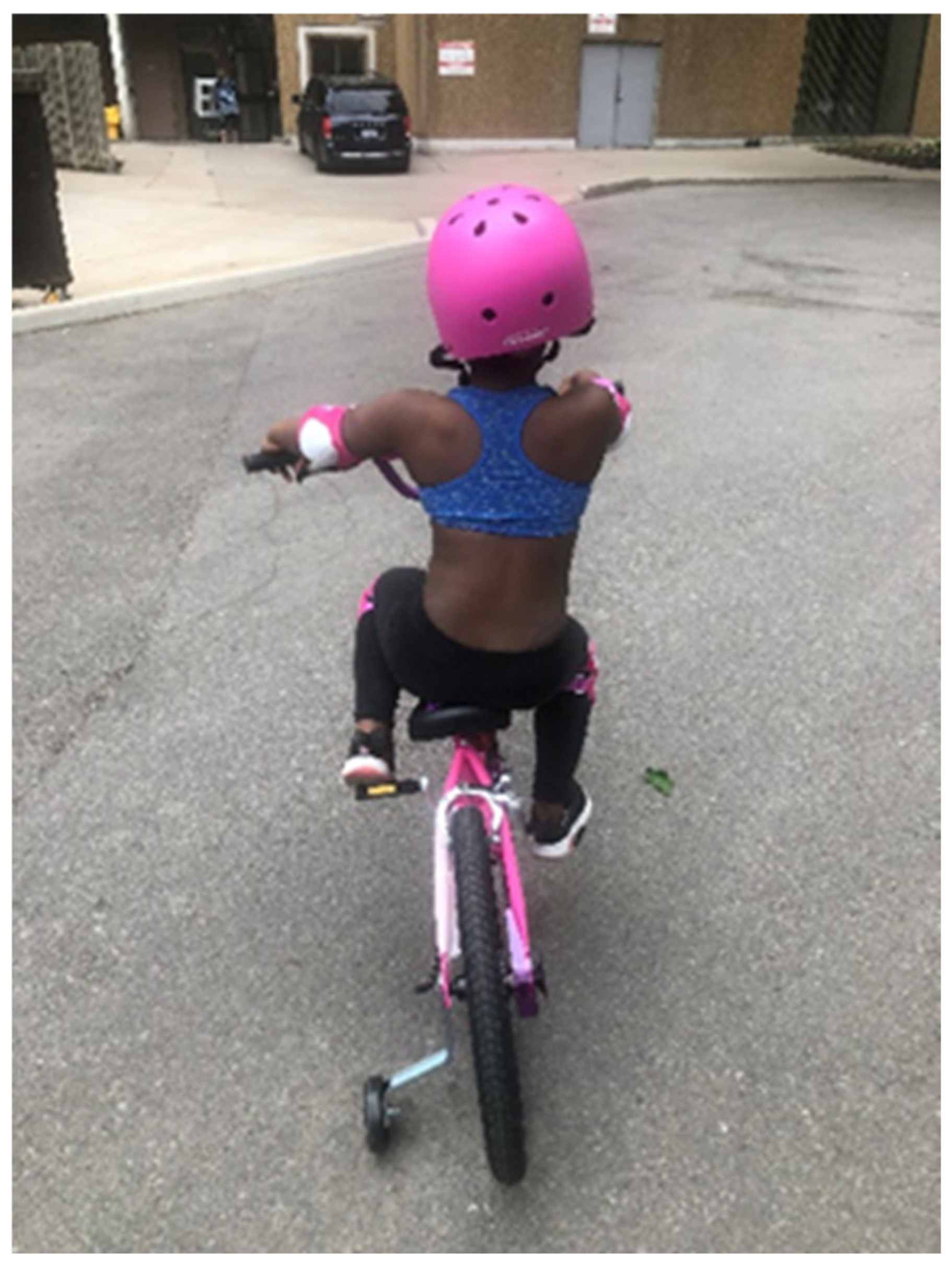

3.1.2. Black Men’s Group

“By separating a family and leaving them with limited resources, you made a situation that was already inadequate, woefully inadequate.”(participant quote, 12 November 2023)

“It has a massive effect on how the black man sees the system and that is why most black men don’t patronize the system. It has to do with their mental health, so all this put together there is a history to it, there is a history to the racism that we are suffering here, and it’s been passed from one generation to another.”(participant quote, 12 November 2023)

“…because oftentimes what you think, is not really what’s happening.”(participant quote, 21 January 2024)

“It’s a condition, at least by society for men to be stoic and sort of forgo the emotional gymnastics involved with daily living.”(participant quote, 12 November 2023)

“…as a dad, you are fighting to survive, fighting to save your kids’ life. And most times that’s where all your energy and efforts go…”(participant quote, 11 December 2023)

“Some families still haven’t been reunited since the incident because of how the police intervened. A lot of families have been destroyed because of procedures and protocols. Do preventive steps and enacted steps that would deescalate, alleviate, and nurture the situation, instead of jumping to separating families and using hostility.”(participant quote, 30 November 2023)

“[It was] hard to get support for individual needs. [It was] a traumatic time, economically stressful.”(participant quote, 12 November 2023)

“We took the first step in talking about it, acknowledging it, and now we are coming together and discussing it, so it’s like we are our own support system”(participant quote, 30 November 2023)

“As we are sharing, a lot of burden has been off-loaded.”(participant quote, 12 November 2023)

“I don’t think we have a problem communicating. I don’t think communication is the problem. It is understanding what we are communicating is the issue.”(participant quote, 30 November 2023)

3.2. Knowledge Exchange Event (KEE)

3.2.1. Idea Generation and Prioritization

3.2.2. Mini Hackathon and Recommendations for Action

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FV | Family Violence |

| IPV | Intimate Partner Violence |

| KEE | Knowledge Exchange Event |

| CSWB | Community Safety and Well=Being |

| PFSN | Peel Family Support Network |

| CBPR | Community-Based Participatory Research |

| CAB | Community Advisory Board |

| PRA | Peer Research Assistant |

| RA | Research Associate |

| EOI | Expression of Interest |

| BAC | Black, African, and Caribbean |

References

- ABR-SD. 2021. Dismantling Anti-Black Racism & Systemic Discrimination: A Toolkit for Community Organizations in the Region of Peel. Brampton: The Anti-Black Racism & Systemic Discrimination Collective of Peel Region. [Google Scholar]

- Arata, Catalina M., Jennifer Langhinrichsen-Rohling, David Bowers, and Laura O’Farrill-Swails. 2005. Single versus multi-type maltreatment: An examination of the long-term effects of child abuse. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma 11: 29–52. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Linda, Anna-Lee Straatman, Nicole Etherington, Brianna O’Neil, Chelsea Heron, and Kayla Sapardanis. 2016. Towards a Conceptual Framework: Trauma, Family Violence and Health. London: Knowledge Hub, Learning Network, Centre for Research & Education on Violence Against Women & Children. Available online: https://www.learningtoendabuse.ca/resources-events/pdfs/Framework_paper-April-20171.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2024).

- Betancourt, Joseph R., Alexander R. Green, and Juan Emilio Carrillo. 2002. Cultural Competence in Health Care: Emerging Frameworks and Practical Approaches. New York: Commonwealth Fund, Quality of Care for Underserved Populations, vol. 576. [Google Scholar]

- Birks, Melanie, Ysanne Chapman, and Karen Francis. 2008. Memoing in qualitative research: Probing data and processes. Journal of Research in Nursing 13: 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braune, Katarina, Pablo-David Rojas, Joscha Hofferbert, Alvaro Valera Sosa, Anastasiya Lebedev, Felix Balzer, Sylvia Thun, Sascha Lieber, Valerie Kirchberger, and Akira-Sebastian Poncette. 2021. Interdisciplinary Online Hackathons as an Approach to Combat the COVID-19 Pandemic: Case Study. Journal of Medical Internet Research 23: e25283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caine, Vera, and Judy Mill. 2016. Essentials of Community-Based Research. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Carrington, Kerry, Christine Morley, Shane Warren, Bridget Harris, Laura Vitis, Matthew Ball, Joanne Clarke, and Vanessa Ryan. 2020. Impact of COVID on Domestic and Family Violence Services and Clients: QUT Centre for Justice Research Report. Brisbane: QUT Centre for Justice. [Google Scholar]

- CASW. 2025. Social Work Practice in Child Welfare. Ottawa: Canadian Association of Social Workers. Available online: https://www.casw-acts.ca/en/social-work-practice-child-welfare (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Chaze, Ferzana, Bethany Osborne, Archana Medhekar, and Purnima George. 2020. Domestic Violence in Immigrant Communities: Case Studies. Toronto: eCampusOntario. [Google Scholar]

- Claeys, Ann, Saloua Berdai-Chaouni, Sandra Tricas-Sauras, and Liesbeth De Donder. 2021. Culturally sensitive care: Definitions, perceptions, and practices of health care professionals. Journal of Transcultural Nursing 32: 484–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comer, James P. 1989. Black fathers. In Fathers and Their Families. London: Routledge, pp. 365–84. [Google Scholar]

- CSWB. 2020. Peel’s Community Safety and Well-Being Plan 2020–2024. Available online: https://peelregion.ca/sites/default/files/2024-03/cswb-plan-2020-2024.pdf (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Draaisma, Muriel. 2024. Ford Says He Has ‘Zero Tolerance’ for Intimate Partner Violence, but Not Yet Declaring It Epidemic. CBC News. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/ontario-intimate-partner-violence-epidemic-ndp-1.7393042 (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Family Child Health Initiative on behalf of the Peel Family Support Network. 2022. A Needs Assessment to Support Collective Action for COVID-19 Pandemic Support and Recovery with Families in the Peel Region. Mississauga: Institute for Better Health. Available online: https://familyandchildhealth.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/PFSN-Needs-Assessment-Report_FINAL_v2.pdf (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Feldner, Katie, and Paula Dutka. 2024. Exploring the evidence: Generating a research question: Using the PICOT framework for clinical inquiry. Nephrology Nursing Journal 51: 393–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierheller, Dianne, Hasha Siddiqui, Cilia Mejia-Lancheros, and Ian Zenlea. 2024a. Picturing Peel’s Active Future: Collective Action for COVID-19 Recovery: Exploring Physical Activity with Youth and Caregivers in Peel Region on. Santa Rosa: Institute for Better Health. Available online: https://familyandchildhealth.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/PA-Community-Report-Final_Jun_28_2030-1.pdf (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Fierheller, Dianne, Rashmi Narkhede, Jamaul Taylor, Midhury Karunanithy, Lavinia Lakhan, Ugonna Ofonagoro, Cameron Thompson, Cilia Mejia-Lancheros, and Ian Zenlea. 2024b. Evaluating the Peel Community Health Ambassador Program: Building Trusting, Equitable, and Responsive Healthcare During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Santa Rosa: Institute for Better Health. [Google Scholar]

- Fierheller, Dianne, Sara Abdullah, Serena Hong, Michelle Vinod, Cilia Mejia-Lancheros, Hasha Siddiqui, and Ian Zenlea. 2024c. A Collaborative Response to Addressing Family Violence with Racialized and Diverse Communities During Pandemic Recovery in Peel Region. Mississauga: Institute for Better Health, Trillium Health Partners. [Google Scholar]

- Fiolet, Renee, Katie Lamb, Laura Tarzia, and Kelsey Hegarty. 2024. A Chance to have a Voice: The Motivations and Experiences of Female Victim-Survivors of Domestic, Family and Sexual Violence who Joined a Lived Experience Research Group. Journal of Family Violence. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, Ruth, Cathy Spatz Widom, Kevin Browne, David Fergusson, Elspeth Webb, and Staffan Janson. 2009. Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. The Lancet 373: 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, Shelley D., Krista M. Perreira, and Christine Piette Durrance. 2013. Troubled times, troubled relationships: How economic resources, gender beliefs, and neighborhood disadvantage influence intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 28: 2134–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, Tasha. 2019. Innovation and Equity in Public Health Research: Testing Arts-Based Methods for Trauma-Informed, Culturally-Responsive Inquiry. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Louisville, Louisville, KY, USA, August 2. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Canada. 2023. Literature Review on the Impacts of Family Violence. Available online: https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/jr/mapafvc-cbapcvf/review-analyse.html (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Government of Ontario. 2017. Child, Youth and Family Services Act; Toronto: Government of Ontario.

- Greer, Alissa M., Ashraf Amlani, Bernadette Pauly, Charlene Burmeister, and Jane A. Buxton. 2018. Participant, peer and PEEP: Considerations and strategies for involving people who have used illicit substances as assistants and advisors in research. BMC Public Health 18: 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, Kathryn L., Myo Thwin Myint, and Charles H. Zeanah. 2020. Increased risk for family violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatrics 146: e20200982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyde-Nolan, Maren E., and Tracy Juliao. 2012. Theoretical basis for family violence. In Family Violence: What Health Care Providers Need to Know. Burlington: Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC, pp. 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, Madeline W. 2022. What Might Encourage the Male Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) Victim to Speak Out to End the Abuse? Minneapolis: Walden University. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, Angie C., Kristen A. Prock, Adrienne E. Adams, Angela Littwin, Elizabeth Meier, Jessica Saba, and Lauren Vollinger. 2024. Can this provider be trusted? A review of the role of trustworthiness in the provision of community-based services for intimate partner violence survivors. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 25: 982–99. [Google Scholar]

- Kessi, Shose. 2011. Photovoice as a practice of re-presentation and social solidarity: Experiences from a youth empowerment project in Dar es Salaam and Soweto. Papers on Social Representations 20: 7.1–7.27. [Google Scholar]

- Kruzan, Kaylee Payne, Jonah Meyerhoff, Candice Biernesser, Tina Goldstein, Madhu Reddy, and David C. Mohr. 2021. Centering lived experience in developing digital interventions for suicide and self-injurious behaviors: User-centered design approach. JMIR Mental Health 8: e31367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, Shanti. 2019. Intersectional trauma-informed intimate partner violence (IPV) services: Narrowing the gap between IPV service delivery and survivor needs. Journal of Family Violence 34: 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Dennis, Anne McAlister, Kathryn Ehlert, Courtney Faber, Rachel Kajfez, Elizabeth Creamer, and Marian Kennedy. 2019. Enhancing research quality through analytical memo writing in a mixed methods grounded theory study implemented by a multi-institution research team. Paper presented at the 2019 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE), Covington, KY, USA, October 16–19. [Google Scholar]

- Lipmanowicz, Henri, and Keith McCandless. 2013. The Surprising Power of Liberating Structures: Simple Rules to Unleash a Culture of Innovation. Seattle: Liberating Structures Press. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, Neena M., Kristin Ward, and Colleen Janczewski. 2008. Coordinated community response to family violence: The role of domestic violence service organizations. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 23: 933–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsiglia, Flavio Francisco, Stephen Stanley Kulis, and Stephanie Lechuga-Peña. 2021. Diversity, Oppression, and Change: Culturally Grounded Social Work. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McMullin, Caitlin. 2023. Transcription and qualitative methods: Implications for third sector research. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 34: 140–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrotra, Gita R., Ericka Kimball, and Stéphanie Wahab. 2016. The Braid That Binds Us: The Impact of Neoliberalism, Criminalization, and Professionalization on Domestic Violence Work. Los Angeles: Sage Publications Sage CA. [Google Scholar]

- MIT Hacking Medicine. 2016. Health Hackathon Handbook. Cambridge: MIT Hacking Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- Niolon, Phyllis Holditch, Megan Kearns, Jenny Dills, Kirsten Rambo, Shalon Irving, Theresa L. Armstead, and Leah Gilbert. 2017. Preventing Intimate Partner Violence Across the Lifespan: A Technical Package of Programs, Policies, and Practices; Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

- Nyarwai, Lucy Kaite, and Cindy-Ann Williams. 2024. Family and Intimate Partner Violence Initiatives and Gender-Based Equity Efforts at the City of Brampton. Available online: https://pub-brampton.escribemeetings.com/filestream.ashx?DocumentId=125109 (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Ocloo, Josephine, Sara Garfield, Bryony Dean Franklin, and Shoba Dawson. 2021. Exploring the theory, barriers and enablers for patient and public involvement across health, social care and patient safety: A systematic review of reviews. Health Research Policy and Systems 19: 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD, Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. 2021. OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19): Towards Gender-Inclusive Recovery; Paris: OECD Publishing.

- O’Neill, Desmond, and Hilary Moss. 2019. Narratives of health and illness: Arts-based research capturing the lived experience of dementia. Dementia 18: 2008–17. [Google Scholar]

- Peel Region. 2023. Family and Intimate Partner Violence. Available online: https://peelregion.ca/health/family-intimate-partner-violence#:~:text=Intimate%20partner%20violence%20is%20an%20epidemic%20in%20Peel&text=In%202023%2C%20Peel%20police%20responded,most%20incidents%20are%20not%20reported (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Peel Region. 2024a. Family, Gender-Based and Intimate Partner Violence: Supporting Pathways to Safety for Victims AMO Conference. Available online: https://peelregion.ca/sites/default/files/2024-08/AMO-2024-Family-Violence-AODA-MTT.pdf (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Peel Region. 2024b. Peel Region Launches Break the Silence Campaign to Raise Awareness on Family and Intimate Partner Violence. Available online: https://peelregion.ca/press-releases/peel-region-launches-break-silence-campaign-raise-awareness-family-intimate-partner-violence#:~:text=In%20June%202023%2C%20Peel%20Region,Quotations (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Photovoice Worldwide. n.d. Photovoice Worldwide. Available online: https://www.photovoiceworldwide.com/ (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Pokharel, Bijaya, Jane Yelland, Leesa Hooker, and Angela Taft. 2023. A systematic review of culturally competent family violence responses to women in primary care. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 24: 928–45. [Google Scholar]

- Previl, Sean. 2025. Intimate Partner Violence Is an ‘Epidemic’. What More Should Be Done? Global News. Available online: https://globalnews.ca/news/10939952/intimate-partner-violence-how-to-spot-holiday-spike/ (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Ragavan, Maya I., Kristie A. Thomas, Anjali Fulambarker, Jill Zaricor, Lisa A. Goodman, and Megan H. Bair-Merritt. 2020. Exploring the needs and lived experiences of racial and ethnic minority domestic violence survivors through community-based participatory research: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 21: 946–63. [Google Scholar]

- Rice, Johnny, Carolyn M. West, Karma Cottman, and Gretta Gardner. 2021. The intersectionality of intimate partner violence in the Black community. In Handbook of Interpersonal Violence and Abuse Across the Lifespan: A Project of the National Partnership to End Interpersonal Violence Across the Lifespan (NPEIV). Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 2705–33. [Google Scholar]

- Riva, John J., Keshena M. P. Malik, Stephen J. Burnie, Andrea R. Endicott, and Jason W. Busse. 2012. What is your research question? An introduction to the PICOT format for clinicians. The Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association 56: 167. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, Louise, and Karen Spilsbury. 2008. Systematic review of the perceptions and experiences of accessing health services by adult victims of domestic violence. Health & Social Care in the Community 16: 16–30. [Google Scholar]

- Saenz, Catherine, Manisha Salinas, Russell L. Rothman, and Richard O. White. 2024. Personalized Lifestyle Modifications for Improved Metabolic Health: The Role of Cultural Sensitivity and Health Communication in Type 2 Diabetes Management. Journal of the American Nutrition Association 44: 198–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seward, Rudy Ray, and Leslie Stanley-Stevens. 2013. Fathers, fathering, and fatherhood across cultures. In Parenting Across Cultures: Childrearing, Motherhood and Fatherhood in Non-Western Cultures. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 459–74. [Google Scholar]

- Shemer, Orna, and Eitan Shahar. 2022. Mixed arts-based methods as a platform for expressing lived experience. In Social Work Research Using Arts-Based Methods. Bristol: Policy Press, pp. 68–76. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Earl. 2008. African American men and intimate partner violence. Journal of African American Studies 12: 156–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokoloff, Natalie J., and Ida Dupont. 2005. Domestic violence at the intersections of race, class, and gender: Challenges and contributions to understanding violence against marginalized women in diverse communities. Violence Against Women 11: 38–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, Meagan A., and Megan L. Haselschwerdt. 2023. Black men’s intimate partner violence victimization, help-seeking, and barriers to help-seeking. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 38: 8849–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweet, Paige. 2021. The Politics of Surviving: How Women Navigate Domestic Violence and Its Aftermath. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Talgorn, Elise, Monique Hendriks, Luc Geurts, and Conny Bakker. 2022. A storytelling methodology to facilitate user-centered co-ideation between scientists and designers. Sustainability 14: 4132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Gregory. 2016. The Chief Public Health Officer’s Report on the State of Public Health in Canada 2016: A Focus on Family Violence in Canada. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/canada/public-health/migration/publications/department-ministere/state-public-health-family-violence-2016-etat-sante-publique-violence-familiale/alt/pdf-eng.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Taylor, Julie C., Elizabeth A. Bates, Attilio Colosi, and Andrew J. Creer. 2022. Barriers to men’s help seeking for intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 37: NP18417–NP44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Equality Institute. 2020. Preventing and Responding to Family Violence: Taking an Intersectional Approach to Address Violence in Diverse Australian Communities. Available online: https://apo.org.au/sites/default/files/resource-files/2017-10/apo-nid185301.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Turner, Tana. 2016. One Vision One Voice: Changing the Ontario Child Welfare System to Better Serve African Canadians. Available online: https://www.oacas.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/One-Vision-One-Voice-Part-1_digital_english-May-2019.pdf (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- United Nations. 2025. International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/observances/ending-violence-against-women-day (accessed on 28 February 2025).

- Valiquette-Tessier, Sophie-Claire, Julie Gosselin, Marta Young, and Kristel Thomassin. 2019. A literature review of cultural stereotypes associated with motherhood and fatherhood. Marriage & Family Review 55: 299–329. [Google Scholar]

- Vandecasteele, Robin, Lenzo Robijn, Sara Willems, Stéphanie De Maesschalck, and Peter A. J. Stevens. 2024. Barriers and facilitators to culturally sensitive care in general practice: A reflexive thematic analysis. BMC Primary Care 25: 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, Bakari A. 2021. A Two-Study Approach to Exploring and Understanding Black Fathers and Black Fatherhood Through the Lived-Paradigm of Antiblackness. Madison: The University of Wisconsin-Madison. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Caroline, and Mary Ann Burris. 1997. Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education & Behavior 24: 369–87. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, Karen. 2018. The Domestic Violence Service System Journey. Ottawa: CanUX. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, Elizabeth N., Jocelyn Anderson, Kathleen Phillips, and Sheridan Miyamoto. 2022. Help-seeking and barriers to care in intimate partner sexual violence: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 23: 1510–28. [Google Scholar]

| (A) | |

| Theme | Brief Description |

| Resilience | This group defines resilience as the internal strength used to overcome challenges. A difficult task in a society filled with blame and a lack of support. |

| Moving On | This theme captures factors associated with moving on in life and saying goodbye to the past—can look like financial freedom, freedom of choice, and freedom to be who they need to be. |

| Protection | Captures the dichotomous nature of things, specifically in the context of sometimes needing protection from the very things needed for our survival. It speaks about the security and comfort of being protected and how protection can come in many forms. |

| Hope and Joy | Describes the factors associated with growth and joy, such as strong support, celebrating milestones, and a hopeful attitude. |

| Overcoming Challenges | Captures the hope required to overcome challenges and the subsequent rewards of doing so, such as, societal freedom, joy, being inspiring, and being contributing members of society. |

| Life Cycle | Captures the cyclical nature of the good and bad times one faces and that every end signifies a new beginning. It also reflects the symmetry between nature and life, such as our multi-faceted yet ever-changing existence. |

| Freedom | Freedom in this theme encompasses freedom from societal expectations and being able to focus on things that brought the participant’s joy. It also captures the importance of looking beyond material comfort for happiness. |

| Understanding Yourself | Captures the importance of self-reflection and understanding yourself. It acknowledges the progress and how far one has come. |

| Love | Captures love in its many forms. This can include self-love, love for others, and the joy of being with loved ones. |

| (B) | |

| Theme | Brief Description |

| Resilience | Explores the strength it takes to overcome challenges. It highlights there is always a light at the end of the tunnel and that resilience and strength can come in many different forms. |

| Black Fatherhood and the System | Captures the experience of black fatherhood, the dedication they have to their children, and how systemic challenges, stereotypes, and biases affect their experiences. |

| Navigating Systems and Missing Links | Highlights the impacts FV creates. It also acknowledges the importance of using an intersectional lens. Individual experiences within the system are oftentimes impacted by factors such as gender, race, etc. |

| Faith in Self | Explores the concepts of personal journeys, growth, identity, and self-confidence. |

| Change | Captures the importance of change in life and change in the current systems that can discriminate against black men. Speaks about controlling the change we wish to see. |

| Safety and Love | Captures the importance of and the desire for safety and love in relationships and in one’s life. As well as the importance of loving yourself. It speaks about the lack of safety and love being detrimental to one’s well-being. |

| Breaking the Silence and Barriers | Captures the harm current gender roles and expectations can have on men and the barriers/taboos they pose. It also highlights the importance of speaking out and breaking those barriers. |

| Thriving and Growth | Explores the concept of overcoming your circumstances, growing, and thriving once again in life. |

| Resilience | Explores the strength it takes to overcome challenges. It highlights there is always a light at the end of the tunnel and that resilience and strength can come in many different forms. |

| Completed Demographic Survey Population [% (n)] (N = 47) | |

|---|---|

| Best Identified Role | |

| Adult (18+) w/Lived Experience | 44.6 (21) |

| Community Partner | 19.1 (9) |

| Researcher | 2.1 (1) |

| Service Provider | 29.8 (14) |

| Other | 4.3 (2) |

| Age | |

| 18–24 | 8.5 (4) |

| 25–34 | 31.9 (15) |

| 35–44 | 29.8 (14) |

| 45–54 | 12.8 (6) |

| 55–64 | 12.8 (6) |

| 65–74 | 4.3 (2) |

| Gender | |

| Woman | 87.2 (41) |

| Man | 8.5 (4) |

| Prefer not to answer | 4.2 (2) |

| Marital Status | |

| Married or Domestic Partner | 40.4 (19) |

| Divorced | 12.8 (6) |

| Separated | 14.9 (7) |

| Single or Never Been Married | 31.9 (15) |

| Racial/Ethnic Group | |

| Asian—East | 2.1 (1) |

| Asian—South | 46.8 (22) |

| Asian—Southeast | 4.3 (2) |

| Black Caribbean | 19. 1 (9) |

| Indian—Caribbean | 4.3 (2) |

| Latin American | 2.1 (1) |

| Middle Eastern | 4.3 (2) |

| White—European | 10.6 (5) |

| White—North American | 2.1 (1) |

| Mixed Heritage | 2.1 (1) |

| Prefer not to answer | 2.1 (1) |

| Highest Level of Education | |

| High school graduate | 6.4 (3) |

| Some college | 6.4 (3) |

| College graduate | 14.9 (7) |

| Some university | 14.9 (7) |

| Undergraduate degree | 17.0 (8) |

| Advanced degree | 34.0 (16) |

| Prefer not to answer | 6.4 (3) |

| Total Family Income | |

| $0 to $29,999 | 23.4 (11) |

| $30,000 to $59,999 | 14.9 (7) |

| $60,000 to $89,000 | 10.6 (5) |

| $90,000 to $119,999 | 6.4 (3) |

| $120,000 to $149,999 | 14.9 (7) |

| $150,000 or more | 10.6 (5) |

| Prefer not to answer | 19.1 (9) |

| # | Generated Idea | Score |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Survivors and instigators of violence should be provided barrier-free and culturally responsive, free-cost, mental health support. | 25 |

| 2 | Access to safe housing to prevent and exit FV. | 23 |

| 3 | Foster empowerment through financial independence. | 20 |

| 4 | Reduce barriers to accessing free wrap-around services and supports. | 20 |

| 5 | Create early-on preventative programs for FV and children through different activities/strategies: culturally appropriate, educational, awareness, communication, and happy and respectful relationships. | 18 |

| 6 | Re-imagine the current “first response” system for FV. Reformulate with more comprehensive mental health support. | 18 |

| 7 | Beginning with community kitchens, create safe and brave spaces for victims of FV (incl. women, children, and men). | 18 |

| 8 | Using media as a form of bringing awareness to FV. Using the radio, tv shows, and apps to educate victims and share their experiences. | 17.5 |

| 9 | Create education programs to promote healthy relationships for groups including parents, caregivers, and seniors. | 17 |

| 10 | Focus on funding for prevention, not just care. | 16.8 |

| 11 | Offering counseling and destigmatizing the taboo that counseling is negative. Starting from parenting education and dismantling emotional immaturity. | 16.8 |

| 12 | Centralized system of data sharing across the system so people with lived experience don’t have to keep proving their experience and having barriers. | 16.5 |

| 13 | More resources and a direct path where people can go to and have reliable help and assistance. More awareness and education regarding FV. | 16.4 |

| 14 | Encourage and support victims with lived experience to be active participants in the educational process of preventing FV. | 16 |

| 15 | Communication between different agencies treating different family members for a holistic support system. | 14 |

| 16 | Establishing a women’s advisory committee to advise the government on trends and policy challenges associated with FV. | 14 |

| 17 | Collaborate with organizations to have monthly awareness projects within communities (ex. mental health month). | 13 |

| 18 | Create a unified platform to collate agenda for change and lobby with the government. | 11.5 |

| 19 | Default acceptance and believing of survivors across the system for people. | 11 |

| 20 | Collaborative efforts involving service providers, community leaders, and lived experience. | Unscored |

| 21 | Food security. By communicating with your community and collaborative efforts for food banks. | |

| 22 | Society has changed but the system hasn’t changed. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abdullah, S.; Hong, S.; Vinod, M.; Siddiqui, H.; Mejía-Lancheros, C.; Irfan, U.; Carter, A.; Zenlea, I.S.; Fierheller, D. A Collaborative Response to Addressing Family Violence with Racialized and Diverse Communities During Pandemic Recovery in Peel Region. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 347. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060347

Abdullah S, Hong S, Vinod M, Siddiqui H, Mejía-Lancheros C, Irfan U, Carter A, Zenlea IS, Fierheller D. A Collaborative Response to Addressing Family Violence with Racialized and Diverse Communities During Pandemic Recovery in Peel Region. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(6):347. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060347

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbdullah, Sara, Serena Hong, Michelle Vinod, Hasha Siddiqui, Cília Mejía-Lancheros, Uzma Irfan, Angela Carter, Ian Spencer Zenlea, and Dianne Fierheller. 2025. "A Collaborative Response to Addressing Family Violence with Racialized and Diverse Communities During Pandemic Recovery in Peel Region" Social Sciences 14, no. 6: 347. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060347

APA StyleAbdullah, S., Hong, S., Vinod, M., Siddiqui, H., Mejía-Lancheros, C., Irfan, U., Carter, A., Zenlea, I. S., & Fierheller, D. (2025). A Collaborative Response to Addressing Family Violence with Racialized and Diverse Communities During Pandemic Recovery in Peel Region. Social Sciences, 14(6), 347. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060347