Indicator Development for Measuring Social Solidarity Economy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Analysis of the Definitions of a Social and Solidarity Economy (SSE)

2.2. Justification for Developing an Operational Definition

2.3. Integration of SSE Principles in Organizational Processes

2.4. Review of Existing Measurement Tools and Identified Gaps

- Defining social policies aligned with the organizational vision;

- Conduction and facilitation of a social diagnosis;

- Setting social goals for programs and projects within an organization;

- Assigning sets of responsibilities to an interdisciplinary group;

- Defining measurable information and planning activities;

- Team training, enabling them to learn about social policies and correct use of the SBS;

- Development of models that incorporate social aims and evaluation indicators;

- Designing and developing flows of information for collecting and assessing data;

- Continuous evaluation of social goals using key data and metrics.

- Characterization: employment, organizational structures and policy frameworks;

- Values, Transparency and Corporate Governance: code of ethics, collaboration with relevant parties, decentralized approach and participation in childcare projects;

- Working Standards: employee relations, medical health and safety, general career advancement, pre-retirement and trade unions;

- Commitment to Environmental Sustainability: business activities and the use of best practices in safeguarding the environment;

- Sustainable Business: nature of the services provided, social welfare activities and socially responsible management and production;

- Food Sovereignty: availability of resources, production and cultivation systems, agricultural and land policies and ethical consumption;

- Solidarity and Reciprocity: establishment and nurturing of supportive social networks;

- Fair Trade: supplier’s assessment, competitive relations, ethical consumptions and social currency.

- Holistic Integration: dimensional inclusion, such as environmental sustainability, social responsibility, and democratic participation align with the multidimensional nature of the SSE measurement framework;

- Comprehensive Indicators: detailed sub-dimensions and indicators provide a solid foundation that can serve as a basis for the development of new SSE indicators, ensuring they encompass the multidimensional aspects of an organization’s impact;

- Subjective and Objective Data Balance: the BV model seeks to integrate subjective, primary data with objective, secondary data at micro-, meso- and macro-levels, thus offering a paradigm that broadens the sources of data for the SSE evaluation;

- Contextual Adaptability: a flexible framework allowing for the adaptation of indicators to geographical and cultural conditions that correspond to a user’s method of applying the SSE instrument across various organizations and sectors.

- Objectives and Scope Determination: define the objectives for assessing solidarity in the context of SSE-based organizations and outline the relevant aspects to be assessed;

- Selection of Indicators: reframe the ESI indicators to an organizational level targeting the practices and outcomes related to solidarity;

- Assessment Basis: set benchmarks for the assessment, which may involve the use of prior performance data or comparisons with comparable similar organizations;

- Graphical Analytical Representation: use graphics (e.g., radar charts) to portray level performance levels across the integration of the newly created solidarity components;

- Interpretation and Actionable Insights: analyze and identify weaknesses, strengths and areas for improvement to enhance solidarity practices and guiding strategic decision making.

- Solidarity in Investment

- Level of participation in microfinance initiatives;

- Number of platforms engaged in solidarity investing;

- Level of impact of investment made toward community development.

- Solidarity in Innovation

- Encourage active participation in knowledge-sharing networks platforms;

- Conduct collaborative research aimed at community-driven innovation;

- Develop strategies and innovative solutions to tackle social issues.

- Ecological Solidarity (Natural Resources)

- Integration of environmentally sustainable practices;

- Measurement of ecological footprint, resource consumption, and pollution indicators;

- Commitment to an innovative green strategy with the goal of reducing pollution.

- Workplace Solidarity

- Number and scope of solidarity enterprises;

- Employee participation in decision-making processes;

- Policy efforts toward ensuring fair conditions and democratic workplaces.

- Rationale for the Dimensional Selection

2.5. Socioeconomic

“The set of private enterprises, formally organized, with decision-making autonomy and freedom of affiliation, created to meet the needs of its members; needs through the market by producing goods and providing services, insurance and finance, where decision making and any distribution of profits or surpluses among members are not directly related to the capital or fees contributed by each member, each of whom has a vote.” Also, the “production of non-market services for households and whose surpluses, if any, cannot be appropriated by the economic agents that create them, control them or finance them”.

2.5.1. SSE Principles

- Surpluses reinvestment for the development of organizations with social and environmental criteria;

- Development of an ethical and supportive financial system based on the principles of collective ownership, participation and transparency;

- Promotion of collective initiatives and solidarity mechanisms;

- The use of tools for measurement, analysis and evaluation to guarantee democratic management and transparency in the redistribution and reinvestment of surpluses;

- Integration of production, distribution, financing and consumption processes into the social market as a shared strategy to increase the positive impacts and transformative potential of SSE and its activities.

2.5.2. Commitment to the Environment

- Establishment of equitable and respectful relationships (i.e., inter-cooperation);

- Use of resources and capabilities considering the capacities of the territory for development, identifying the needs arising from injustices and inequality in the territorial environment;

- Promoting active local community participation in safe spaces based on mutual care;

- Connecting and revaluing rural and urban areas for the resilience of the territorial organization;

- Disseminate proposals for SSE-based actions, objectives and results through appropriate and accessible instruments and communication channels;

- Actively participate in local networks and social movements that promote transformative actions;

- Develop and promote diverse practices, such as eco-feminist and non-discriminatory actions;

- Influence public policies for the construction of strategies that develop the environment from the perspective of good living.

2.5.3. Principles and Values (P&V) Within an SSE

- Self-managementIn a democratic economy (DE), individuals have control over decisions that affect their lives. With self-management, voting is contemplated for inclusion in decision making in proportion to the degree to which each individual is directly affected and the degree to which the majority is affected. This model by Hahnel (2013) considers a council of workers who have greater influence in the performance of the activity. In a democratic economy, however, because of the complexity, every decision that affects an approximation of this number of people is made using a design that allows those affected to have a say.

- Justice and rewards for personal sacrificeIn a DE, rewards are given according to the contribution of work and degree of sacrifice and effort by the individual, whether related to work or training. That is, an individual can decide on the degree of sacrifice without it being a detriment to their well-being, having control over their time and that within their reach. An example of something not in their control would be athletic talent or knowledge that requires a high degree of specialization. For this, a measure is proposed that recognizes commensurate differences in skills and benefits.

- SolidaritySolidarity, according to an empirical analysis by Razeto (2017), is denoted as the “C” factor. It is observed, via SocE initiatives, that although they use low-productive road technology, low-quality materials and an unqualified labor force, as well as have poor access to capital, they are able to stay productive. The “C” factor refers to the driving force behind productive outcomes that drive unions due to shared objectives and the collective conscious of individuals. Concern for the well-being of others is fundamental in this model; it introduces solidarity into the economy in a different way, integrating it into all of its processes, including production, distribution, consumption and accumulation (Páez Pareja 2017).

- Diversity (the flourishing of lifestyles and outcomes)“Since humans display a wide variety of preferences, tastes, potentials, and lifestyles, the best life for one is not necessarily the best life for another. Diversity is about rejecting conformity, homogenization, and regimentation in favor of a flourishing variety of choices and outcomes in our lives. The other benefit of diversity is not putting all our eggs in one basket. It is important to experiment with different ideas, explore different options, and encourage minority viewpoints, in case one path turns out to be wrong” (Participatory Economy Project 2023).

- Efficiency (meeting goals without wasting time and resources on tasks)In this economic model, efficiency refers to achieving economic goals by minimizing the waste of resources, time, labor, and energy (Participatory Economy Project 2023). An example of this is agency theory in management, where shareholders (principals) establish relationships with managers (agents), which can generate distrust. This often results in costs related to monitoring agent behavior through policies and other control mechanisms, exemplifying an aspect of corporate governance. An example at the operational level includes requiring workers to follow a fixed schedule when the task could be completed in a shorter amount of time.

- Environmental Sustainability (ES) (Protection and care of the natural environment)ES is presented here as a principle. Although we have presented it as a macro-dimension, as stated above, however, converging factors prevent dimensions from fully being decoupled or isolated from one another, based on the notion that principles and values are embedded within these dimensions.

2.6. Environmental Sustainability (ES)

- Ecological dimension: aspects related to preserving and enhancing the diversity and complexity of ecosystems and their productivity, natural cycles and biodiversity;

- Social dimension: equitable access to the goods of nature, both in intergenerational and intragenerational terms, between genders and between cultures, between groups and social classes, and also at the level of the individual;

- Economic dimension: requires redefinition of the concepts of the traditional economy, especially the needs, both material and immaterial, and satisfactions of human beings;

- The political dimension: direct participation by people in the decision-making process, in defining collective and possible futures, in management structures for public goods and the content of democracy.

- Some damage to the environmental system is irreversible;

- Some alterations to the system are uncertain;

- Damage to the environmental system is cumulative;

- Knowledge of resource reserves is uncertain;

- Nothing (or very little) is known about future technologies;

- It is not possible to reduce the diversity of units of the environmental system even to a common unit;

- Current or future monetary valuations are arbitrary;

- “Exported” impacts associated with imported products are not taken into account (Wolf et al. 2022).

- Ecological Footprint (Wackernagel 2001) “It is the area of productive territory or aquatic ecosystem necessary to produce the resources used and to assimilate the waste produced by a population”;

- Environmental Space (Spangenberg et al. 1999) “It is the amount of renewable and non-renewable natural resources that we can use (and the levels of waste and pollution that we can afford) without depriving future generations of their right to the same use of natural resources” (Achkar et al. 2005);

- Carbon Footprint as an indicator to measure Carbon dioxide Gases (CO2), the carbon offsets case considered policy approaches to pricing carbon dioxide in a market environment (McCowen 2017) however it has its controversies.

- Energy and non-renewable raw materials, global resource;

- Wood and agricultural products, continental resources;

- Water, local or regional resources, catchment area.

2.7. Social Innovation (SI)

2.8. Democratic Governance

“Promote the creation of dignified, equitable labor conditions as well as inclusive participation in a democratic decision-making process in SSE activities, guaranteeing fair salary, respect for workers’ rights, social protection, equal rights regarding gender, ethnicity and age. Also taking into account constant upkeep on democratic management, financial autonomy and member solidarity, entailing the promotion of equitable resource distribution as well as benefits to people and nature in a sustainable manner, in order to achieve an overall well-being”

2.8.1. Methods Addressing Governance in the SSE

2.8.2. Governance as a Dimension in the Literature

2.8.3. Governance in Social Innovation

- Measure the change in attitudes of local actors toward cooperation and innovation, reflecting their willingness to adopt new practices.

- Account for new governance arrangements created, such as second-degree associations and cooperatives.

- Assess the level of coordination among actors, distinguishing between communication, cooperation and collaboration.

2.9. Responsible Production and Consumption

3. Method

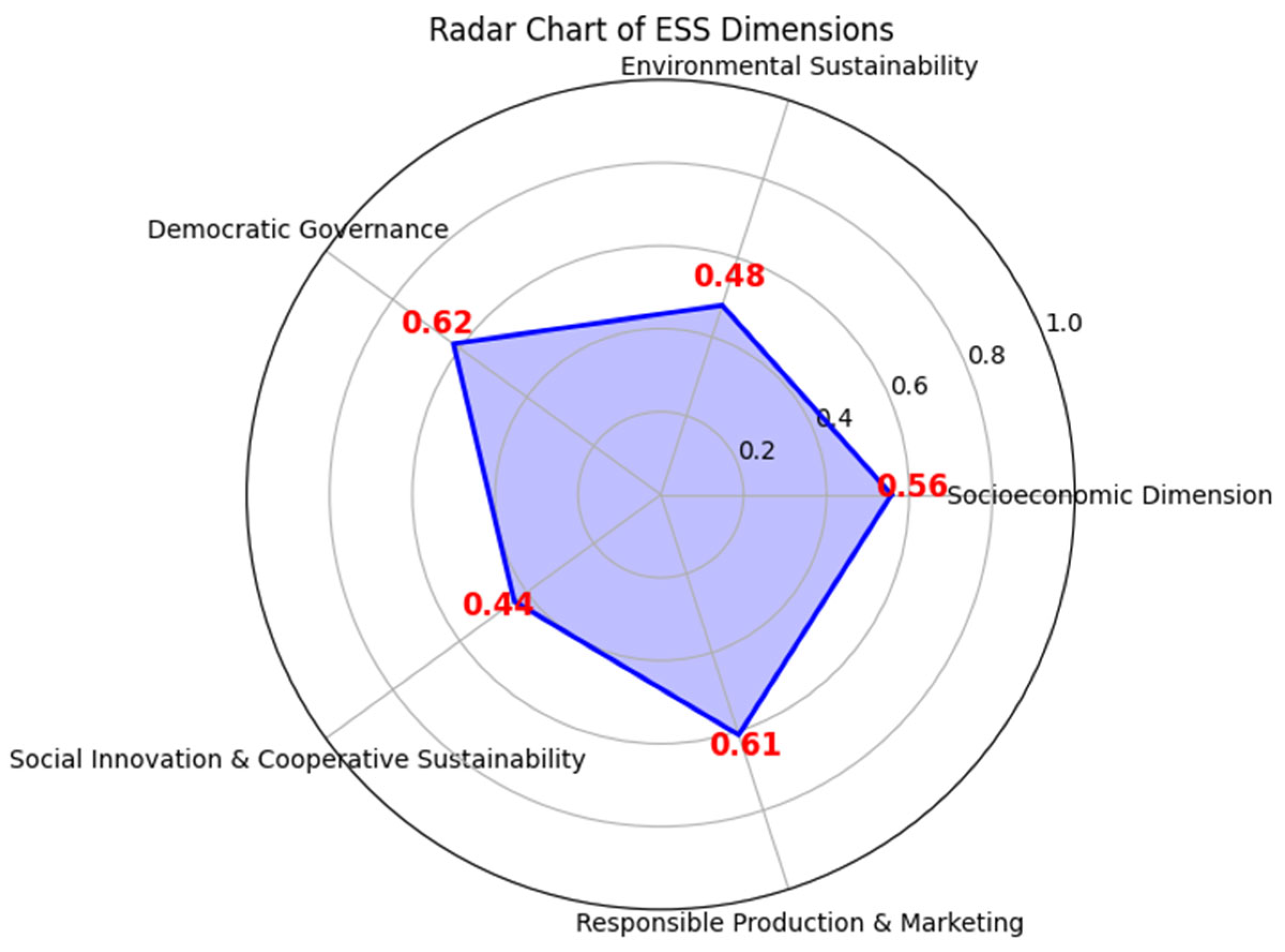

Dimensional Findings and Instrumental Lay-Out

4. Results

Instrumental Result Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Achkar, Marcel, Víctor Canton, Ricardo Cayssials, Ana Domínguez, Gabriel Fernández, and Fernando Pesce. 2005. Indicadores del Desarrollo Sustentable: El Ordenamiento Ambiental del Territorio. Comisión Sectorial de Educación Permanente. DIRAC, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de la República. Available online: https://cmapspublic.ihmc.us/rid=1W78HHVG1-2204K4H-K6/Indicadores.pdf (accessed on 3 October 2023).

- Alarcón Conde, Miguel Ángel. 2011. Incidencia de la economía solidaria en las cuentas nacionales: Hacia una identificación de la necesidad y un mapeo de la experiencia Europea. In Innovación y economía social y solidaria: Retos y aprendizajes de una gestión diferenciada. Edited by Juan Fernando Álvarez. Barranquilla: Ibarra Garrito Promotores LTDA, pp. 39–74. [Google Scholar]

- Alix, Nicole. 2015. Mesure de l’impact social, mesure du consentement à investir. Revue Internationale de L’économie Sociale 335: 111–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arena, Marika, Giovanni Azzone, Irene Bengo, and Mario Calderini. 2016. Indicators and metrics for social business: A review of current approaches. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 7: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askunze Elizaga, Carlos, and María Angeles Díez López. 2021. Mercado social: Estrategia de despliegue de la economía solidaria. Revista Economía 72: 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayres, Robert Underwood, Jeroen Cjm Van Den Bergh, and John M. Gowdy. 1998. Viewpoint: Weak versus Strong Sustainability. Tinbergen Institute Discussion Paper. Amsterdam and Rotterdam: Tinbergen Institute. Available online: https://research.vu.nl/ws/portalfiles/portal/2204102/98103.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2023).

- Álvarez Rodríguez, Juan Fernando. 2017. Economía Social y Solidaria en el Territorio: Significantes y Co-Construcción de Políticas Públicas. Bogotá: Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. Available online: https://repositorio.coomeva.com.co/server/api/core/bitstreams/6dca4a0e-b08d-4ae8-86cd-49f5feaf671c/content (accessed on 3 October 2023).

- Bhattacherjee, Anol. 2012. Social Science Research: Principles, Methods, and Practices. Tampa: University of South Florida. [Google Scholar]

- Bilsborough, Joe, Joe Guinan, and Thomas M. Hanna. 2018. The ‘Preston Model’ and the Modern Politics of Municipal Socialism. Open Democracy, June 12. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/39696129/The_Preston_Model_and_the_modern_politics_of_municipal_socialism (accessed on 3 November 2023).

- Bonfil, Conde. 2020. Conceptos relacionados con la economía social y modelos de las empresas sociales en México. IBERO 1: 135–77. Available online: https://ri.ibero.mx/bitstream/handle/ibero/4808/SMTE_NE__01_02_135.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 20 September 2023).

- Bouchard, Marie J., and Damien Rousselière. 2022. Recent advances on impact measurement for the social and solidarity economy: Empirical and methodological challenges. Wiley International Studies of Economics 93: 253–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchard, Marie J., and Gabriel Salathé-Beaulieu. 2021. Available online: https://knowledgehub.unsse.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/WP-2021-SSE-Stats-Bouchard-Salathe-Beaulieu.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Cacciari, Paolo. 2018. Economie solidali creatrici di comunità ecologiche. Scienze del Territorio 6: 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbo, Jerry, Ian M. Langella, Viet T. Dao, and Steven J. Haase. 2014. Breaking the ties that bind: From corporate sustainability to socially sustainable systems. Business and Society Review 119: 175–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreras Roig, Lluís, and Ramon Bastida Vialcanet. 2015. Estudio sobre la rendición de cuentas en materia de responsabilidad social: El balance social. Ciriec-España, Revista de Economía Pública, Social y Cooperativa 82: 251–77. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/174/17442313009.pdf (accessed on 2 October 2023). [CrossRef]

- Catani, Antonio David, Jose Luis Coraggio, and Jean-Louis Laville. 2009. Diccionario de Otra Economía. Buenos Aires: CLACSO, Universidad Nacional de General Sarmiento, y Editorial Altamira. [Google Scholar]

- Chalub, Wladislau Guimarães Silva. 2018. Estudo das Práticas de Gestão dos Empreendimentos Econômicos Solidários no Âmbito Regional: Análise Multicaso nas Cooperativas Incubadas de Reciclagem. Uberlândia: Universidade Federal de Uberlândia. [Google Scholar]

- Chaves, Rafael, and José Luis Monzón Campos. 2019. Evolución Reciente de la Economía Social en la Unión Europea. No. 1903. Liège: CIRIEC-Université de Liège. Available online: https://www.zbw.eu/econis-archiv/bitstream/11159/2896/1/WP2019-03ESP.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2023).

- Coraggio, Jose Luis. 2007. El Papel de la Economía Social y Solidaria en la Estrategia de Inclusión Social. FLACSO y SENPLADES. Buenos Aires, Argentina. Available online: http://base.socioeco.org/docs/decisio29_saber4.pdf (accessed on 6 July 2023).

- Daly, Herman E., and Joshua Farley. 2011. Ecological Economics: Principles and Applications, 2nd ed. Washington, DC: Island Press. [Google Scholar]

- Defourny, Jacques, and Marthe Nyssens. 2014. Social co-operatives: When social enterprises meet the co-operative tradition. Journal of Entrepreneurial and Organizational Diversity 2: 11–33. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/Delivery.cfm/SSRN_ID2437884_code1714152.pdf?abstractid=2437884&mirid=1 (accessed on 4 July 2023).

- Déleg, Nancy. 2016. EJE 3. Economía social y solidaria. In Exploración de Indicadores Para la Medición Operativa del Concepto del Buen Vivir. Edited by Universidad de Cuenca. Ecuador: Editorial Don Bosco-Centro Gráfico Salesiano, pp. 99–123. [Google Scholar]

- ECLAC. 2007. Serie Estudios y Perspectivas. Indicadores de Capacidades Tecnológicas en América Latina. México: Naciones Unidas. Available online: https://repositorio.cepal.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/7e659681-67b3-46a7-826e-d49e9500bbd3/content (accessed on 3 July 2023).

- ECODES. 2023. Medición, Gestión y Evaluación Impacto. May 18. Available online: https://ecodes.org/hacemos/cultura-para-la-sostenibilidad/medicion-y-evaluacion-de-impacto/sroi-metodologia-para-la-medicion-del-impacto-social-ambiental-y-socioeconomico (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Eizaguirre Anglada, Santiago. 2016. De la innovación social a la economía solidaria. Claves prácticas para el desarrollo de políticas públicas. CIRIEC-España, Revista de Economía Pública, Social y Cooperativa 88: 201–30. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/2445/123562 (accessed on 20 October 2023).

- Elkington, John. 1994. Towards the Sustainable Corporation: Win-Win-Win Business Strategies for Sustainable Development. California Management Review 36: 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar Delgadillo, Jéssica Lorena. 2008. El desarrollo sustentable en México (1980–2007). Revista Digital Universitaria. p. 4. Available online: https://www.revista.unam.mx/vol.9/num3/art14/art14.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2023).

- Esteves, Ana Margarida, Audley Genus, Thomas Henfrey, Gil Penha-Lopes, and May East. 2021. Sustainable entrepreneurship and the Sustainable Development Goals. Business Strategy and the Environment 30: 1423–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etxezarreta, Enekoitz, Aitziber Etxezarreta, Mikel Zurbano, and Miren Estensoro. 2014. La Innovación Social en la Economía Social y Solidaria: Un Marco Teórico y Metodológico para las Entidades de REAS. Bilbao: Universidad del País Vasco y Orkestra, Instituto Vasco de la Competitividad. [Google Scholar]

- Felber, Christian, and Gus Hagelberg. 2020. The Economy for the Common Good: A Workable, Transformative, Ethics-Based Alternative. In The New Systems Reader. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 39–57. [Google Scholar]

- Fisa, A. G. 1995. NTP 305: Tipos de Indicadores para el Balance Social de la Empresa. Centro Nacional de Condiciones de Trabajo. Available online: https://www.cso.go.cr/legislacion/notas_tecnicas_preventivas_insht/NTP%20305%20-%20Tipos%20de%20indicadores%20para%20el%20balance%20social%20de%20la%20empresa.pdf (accessed on 4 July 2023).

- Fonteneau, Bénédicte, Nancy Neamtam, Fredrick Wanyama, Leandro Pereira Morais, and Mathieu De Poorter. 2010. Social and Solidarity Economy: Building a Common Understanding. Turin: International Training Centre of the International Labour Organization. Available online: https://base.socioeco.org/docs/social_and_solidarity_economy_en.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2023).

- Francés, Francisco, Fernando Vega, Sebastián Endara, Jenny Albarracín, Alexander Arias, Javier Ávila, Daniel Encalada, Margarita Guillén, Nancy Déleg, and Antonio Alaminos. 2016. Exploración de Indicadores para la Medición Operativa del Concepto del Buen Vivir. Don Bosco-Centro Gráfico Salesiano. Available online: http://dspace.ucuenca.edu.ec/handle/123456789/25911 (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Fresco, Jaques Fresco. 2007. Designing the Future; The Venus Project, Inc. Available online: https://files.thevenusproject.com/hotlink-ok/designing_the_future_ebook/Jacque%20Fresco%20-%20Designing%20the%20Future.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2024).

- Frère, Bruno. 2018. Solidarity Economy and Its Anarchist Grammar. Liège: Université de Liège, Faculté des Sciences Sociales, Sociologie des Identités Contemporaines. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/2268/191320 (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- Goncharenko, Oleksii, Oksana Hrynevych, Orlando Petiz Pereira, and Chama Theodore Ketuama. 2021. Concept approach for measuring solidarity economy in agriculture. Paper presented at International Scientific Conference, Contemporary Issues in Business, Management and Economics Engineering 2021, Vilnius, Lithuania, May 13–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonin, Michael, Jean-Christopher Zuchuat, Nicolas Gachet, and Laurent Houmard. 2013. Toward a statistically robust assessment of social and solidarity economy actors: Conceptual development and empirical validation. Paper presented at 4th EMES International Research Conference on Social Enterprise, Liège, Belgium, July 1–4; Zürich: Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich, pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Calvo, Verónica. 2013. Acercamiento a las prácticas de la economía social, la economía solidaria y la economía del bien común: ¿Qué nos ofrecen? Barataria. Revista Castellano-Manchega de Ciencias Sociales 15: 112–24. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/3221/322128446006.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2023).

- Guérin, Isabelle, and Miriam Nobre. 2014. Solidarity Economy Revisited in the Light of Gender: A Tool for Social Change or Reproducing the Subordination of Women? In Under Development: Gender. Gender, Development and Social Change. Edited by Christine Verschuur, Isabelle Guérin and Hélène Guétat-Bernard. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 286–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillén, Alejandro, and Mauricio Phélan. 2016. Las mediciones del desarrollo y bienestar desde Latinoamérica: Desde la CEPAL hasta el Buen Vivir (Sumak Kawsay). In Exploración de Indicadores para la Medición Operativa del Concepto del Buen Vivir. Edited by Alejandro Guillén. Ecuador: Editorial Don Bosco-Centro Gráfico Salesian, pp. 23–39. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/libro?codigo=725378&orden=1&info=open_link_libro (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Hahnel, Robin. 2013. Economic Justice and Democracy: From Competition to Cooperation. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández Ramos, Ernando Luciano, Klever Aníbal Guamán Chacha, and Cesar Eduardo Ochoa Díaz. 2021. El incumplimiento de los principios del sistema económico popular y solidario afecta al desarrollo productivo de la sociedad ecuatoriana. Dilemas Contemporáneos: Educación, Política y Valores 8: 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrynevych, Oksana, and Oleksii Sergiyovych Goncharenko. 2018. Enfoque Científico y Metodológico para Evaluar el Nivel de Solidaridad de la Economía. Paper presented at the XXXII Congreso Internacional de Economía Aplicada, ASEPELT 2018, Huelva, Spain, July 4–7; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/332269517 (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). 2022. Estudio de Caso Sobre la Economía Social de México, 2013 y 2018 [Comunicado de Prensa núm. 713/22]. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/saladeprensa/boletines/2022/ES/EconomiaSocial2013-2018.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2023).

- Instituto Nacional de la Economía Social Solidaria. 2023. Cuenta Satélite de la Economía Social. Gobierno de México. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/inaes/prensa/cuenta-satelite-de-la-economia-social?idiom=es (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- International Labour Organization (ILO), Asociación Nacional de Industriales (ANDI), and Capítulo Antioquia Cámara Junior de Colombia. 2001. Manual de Balance Social: Versión Actualizada, 2nd ed. Geneva: OIT. Colombia: ANDI. Available online: https://eco.mdp.edu.ar/cendocu/repositorio/01128.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2023).

- Jain, S. P., and Wim Polman. 2003. The Panchayati Raj Model in India; RAP Publication 2003/07. Bangkok: FAO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific. Available online: http://www.fao.org/docrep/pdf/007/AE536e/AE536E00.pdf (accessed on 5 July 2023).

- Jessop, Bob, Frank Moulaert, Lars Hulgård, and Abdelillah Hamdouch. 2013. Social innovation research: A new stage in innovation analysis. In The International Handbook on Social Innovation: Collective Action, Social Learning and Transdisciplinary Research. Edited by Frank Moulaert, Diana MacCallum, Abid Mehmood and Abdelillah Hamdouch. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 110–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keurhorst, Noortje. 2020. Measuring Social Value in the Social Solidarity Economy. Doctoral Thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands. Available online: https://library.wur.nl/WebQuery/theses/2294978 (accessed on 10 August 2023).

- Kirdina, Svetlana. 2016. The Solidarity Economy: Forgotten Social Innovation or Contemporary Institution to Counter the Power of Vested Interests? Moscow: Institute of Economics, Russian Academy of Sciences, pp. 1–10. Available online: https://www.aeaweb.org/conference/2017/preliminary/paper/daFh3FFe (accessed on 4 July 2024).

- Klein, Juan-Luis. 2017. La innovación social: ¿Un factor de transformación? FORO 1: 9–26. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Juan-Luis-Klein/publication/319086266_La_Innovacion_Social_Un_Factor_de_Transformacion_FORO_Julio-Agosto_vol_1_num_1_2017/links/598f0d2faca2721d9b656f08/La-Innovacion-Social-Un-Factor-de-Transformacion-FORO-Julio-Agosto-vol-1-num-1-2017.pdf?_tp=eyJjb250ZXh0Ijp7ImZpcnN0UGFnZSI6InB1YmxpY2F0aW9uIiwicGFnZSI6InB1YmxpY2F0aW9uIn19 (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Kleverbeck, Maria, Gorgi Krlev, Georg Mildenberger, Simone Strambach, Jan-Frederik Thurmann, Judith Terstriep, and Laura Wloka. 2019. Indicators for measuring social innovation. In Atlas of Social Innovation, 2nd ed. Munich: Oekom, pp. 98–101. Available online: https://www.socialinnovationatlas.net/fileadmin/PDF/volume-2/01_SI-Landscape_Global_Trends/01_21_Indicators-for-Measuring-SI_Kleverbeck-Krlev-Mildenberger-Strambach-Thurmann-Terstriep-Wloka.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2023).

- Klimczuk, Andrzej, and Magdalena Klimczuk-Kochańska. 2015. Economía social y solidaria. In La Enciclopedia SAGE de la Pobreza Mundial, 2nd ed. Edited by M. Odekon. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications, pp. 1413–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara Gómez, Graciela, and Carolina Carla Pérez Hernández. 2015. Responsabilidad social y desarrollo sustentable: Su medición y alcance en la economía social y solidaria. En IX Congreso RULESCOOP: Cooperativismo e innovación social en México (La Plata, 2015). Facultad de Ciencias Económicas. Available online: https://sedici.unlp.edu.ar/handle/10915/49902 (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Laville, Jean-Louis. 2015. Social and solidarity economy in historical perspective. In Social and Solidarity Economy: Beyond the Fringe. Edited by Peter Utting. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, pp. 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Mike, and Dan Swinney. 2007. Social Economy? Solidarity Economy?: Exploring the Implications of Conceptual Nuance for Acting in a Volatile World; Port Alberni: Canadian Centre for Community Renewal (CCCR). Available online: https://base.socioeco.org/docs/f3_-_lewis_swinney.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- Ley de la Economía Social y Solidaria (LESS). 2023. Reglamentaria del párrafo octavo del artículo 25 de la Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos. Última Reforma Publicada en el DOF, 29 de Diciembre de 2023. Diario Oficial de la Federación. Available online: https://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/pdf/LESS.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Machín, Odalys Labrador, Juan Luis Alfonso, and Claudio Alberto Rivera. 2017. Enfoques sobre la economía social y solidaria. Cooperativismo y Desarrollo: COODES 5: 137–46. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/6231786.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2023).

- Maji, Sumit Kumar. 2017. Assessing the role of South-South and triangular cooperation in achieving sustainable development goals: Evidence from IBSA countries. SSRN, June. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2975425 (accessed on 3 November 2023). [CrossRef]

- McCowen, Tracey. 2017. Emission Permits as a Monetary Policy Tool: Is It Feasible? Is it Ethical? Doctoral Thesis, Universidad de Vermont, Burlington, VT, USA. Available online: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/graddis/811/ (accessed on 7 October 2023).

- Monzón, Jose Luis, and Rafael Chaves. 2012. The social economy: An international perspective. CIRIEC-España, Revista de Economía Pública, Social y Cooperativa 73: 4–8. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/174/17421160001.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2023).

- Morais, Leandro Pereira, and Miguel Juan Bacic. 2020. Contribuciones de la economía social y solidaria a la implementación de los objetivos de desarrollo sostenible y a la construcción de indicadores de evaluación: El caso de un asentamiento en Araraquara, Brasil. Calitatea Vieții 31: 70–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morett-Sánchez, J. Carlos, and Celsa Cosío-Ruiz. 2017. Panorama de los ejidos y comunidades agrarias en México. Agricultura, Sociedad y Desarrollo 14: 125–46. Available online: https://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1870-54722017000100125 (accessed on 20 March 2024). [CrossRef]

- Moulaert, Frank, and Oana Ailenei. 2005. Social economy, third sector and solidarity relations: A conceptual synthesis from history to present. Urban Studies 42: 2037–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novillo, Martin Elena. 2015. La economía social y solidaria: Una economía para las personas. Revistas Economistas 22: 50–56. Available online: https://www.economiasolidaria.org/recursos/biblioteca-la-economia-social-y-solidaria-una-economia-para-las-personas/ (accessed on 27 February 2024).

- OECD. 2014. OECD Data: Trusted Statistics Supporting Evidence-Based Policy. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/data.html (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- OECD. 2021. Social Impact Measurement for the Social and Solidarity Economy: OECD Global Action Promoting Social & Solidarity Economy Ecosystems. OECD Local Economic and Employment Development (LEED) Papers, No. 2021/05. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2023. OECD Global Action on Promoting Social Solidarity Economy Ecosystems: Country Fact Sheet Mexico. July 17. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/cfe/leed/social-economy/oecd-global-action/country-fact-sheet-mexico.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2023).

- Participatory Economy Project. 2023. Overview of the Model. Available online: https://participatoryeconomy.org/the-model/overview/ (accessed on 23 August 2023).

- Páez Pareja, Jose Ramon. 2017. El Balance Social Como Herramienta de Gestión Integral para las Organizaciones de la Economía Social. Doctoral Thesis, Universidad Pablo de Olavide, Teseo, Sevilla, Spain. Available online: https://www.educacion.gob.es/teseo/imprimirFicheroTesis.do?idFichero=T3%2FLJq602PA%3D (accessed on 15 February 2024).

- Raffaelli, Paola. 2016. Social and Solidarity Economy in a Neoliberal Context: Transformative or Palliative? The Case of an Argentinean Worker Cooperative. Journal of Entrepreneurial and Organizational Diversity 5: 33–53. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2920633 (accessed on 5 June 2024). [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Razeto, Luis. 2017. El “Factor C”: La Fuerza de la Solidaridad en la Economía (Entrevista). Luis Razeto. Available online: http://luisrazeto.net/content/el-factor-c-la-fuerza-de-la-solidaridad-en-la-economia-entrevista (accessed on 4 December 2023).

- Red de Redes de Economía Alternativa y Solidaria (REAS). 2022. Carta de Principios de la Economía Solidaria. Available online: https://www.economiasolidaria.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Carta_de_la_Econom%C3%ADa_Solidaria_2022_cast.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2023).

- Registro Agrario Nacional. n.d. Nota Técnica Sobre la Propiedad Social; Secretaría de Desarrollo Agrario, Territorial y Urbano. Available online: http://www.ran.gob.mx/ran/indic_bps/NOTA_TECNICA_SOBRE_LA_PROPIEDAD_SOCIAL_v26102017 (accessed on 10 February 2024).

- Ressel, Alicia Beatriz, and Viviana Coppini. 2012. El balance social y su importancia como instrumento de medición en las organizaciones de la economía social, particularmente en las cooperativas. Paper presented at VII Congreso Internacional Rulescoop-Economía Social: Identidad, Desafíos y Estrategias, Valencia-Castellón, Spain, September 5–7; Buenos Aires: Instituto de Estudios Cooperativos (IECOOP). Available online: http://sedici.unlp.edu.ar/handle/10915/43726 (accessed on 22 February 2024).

- Restrepo, Edison Valencia. 2023. La innovación Social como un Apoyo para Mitigar Problemáticas Glocales. Trabajo de grado, Universidad Nacional Abierta y a Distancia—UNAD, Escuela de Ciencias Sociales, Artes y Humanidades—ECSAH, Programa de Sociología, Diplomado en Innovación Social. Available online: https://repository.unad.edu.co/bitstream/handle/10596/56273/erestrepov.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- Ridley-Duff, Rory. 2015. The Case for FairShares: A New Model for Social Enterprise Development and the Strengthening of the Social and Solidarity Economy. Scotts Valley: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. [Google Scholar]

- Rieiro, Aanabel. 2021. Social and Solidarity Economy in Uruguay. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Latin American History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rissotto, Hernán Oscar. 2015. El Balance Social y el Desempeño Social de las Empresas. Available online: https://repositorio.uca.edu.ar/handle/123456789/2233 (accessed on 3 April 2024).

- Rojas Herrera, Juan Jose. 2023. Decepcionante el crecimiento de la Economía Social. La Coperacha. March 21. Available online: https://lacoperacha.org.mx/decepcionante-crecimiento-economia-social (accessed on 4 April 2024).

- Rotheroe, Neil C., and Liz Miller. 2008. Innovation in social enterprise: Achieving a user participation model. Social Enterprise Journal 4: 242–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saïd, I., P. Ladd, and I. Yi. 2018. Measuring the Scale and Impact of Social and Solidarity Economy. Issue Brief. UNRISD. Available online: https://cdn.unrisd.org/assets/library/briefs/pdf-files/ib9-measurement-sse.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2024).

- Salathé-Beaulieu, Gabriel, Marie J. Bouchard, and Marguerite Mendell. 2019. Sustainable Development Impact Indicators for Social and Solidarity Economy: State of the Art. Working Paper. Geneva: United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD). Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/246230/1/WP2019-04.pdf (accessed on 3 December 2023).

- Salvatori, Gianluca. 2018. International Co-Operative Alliance Global Conference and General Assembly: The topics at the centre of the international dialogue. Journal of Entrepreneurial and Organizational Diversity 6: 75–79. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3147565 (accessed on 20 January 2024). [CrossRef]

- Santana, María Eugenia. 2014. Reciprocidad y redistribución en una economía solidaria. Ars & Humanitas 8: 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savall Vercher, Néstor. 2021. Innovación social y Desarrollo Territorial: Estudio de Casos en Áreas Rurales de España y Escocia. Doctoral Thesis, Universitat de València, Valencia, Spain. Dialnet. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/tesis?codigo=298303 (accessed on 12 December 2023).

- Secretaría Nacional de Planificación y Desarrollo [Senplades]. 2013. Plan Nacional para el Buen Vivir 2013–2017. Quito: Secretaría Nacional de Planificación y Desarrollo. Available online: https://observatorioplanificacion.cepal.org/sites/default/files/plan/files/Ecuador%20Plan%20Nacional%20del%20Buen%20Vivir.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2023).

- Sotiropoulou, Irene. 2020. Social and solidarity economy: A quest for appropriate quantitative methods. Review of Economics & Economic Methodology 6: 131–56. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Irene-Sotiropoulou-2/publication/344099827_Social_and_Solidarity_Economy_A_Quest_for_Appropriate_Quantitative_Methods/links/5f521dfb458515e96d2b7307/Social-and-Solidarity-Economy-A-Quest-for-Appropriate-Quantitative-Methods.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2023).

- Spangenberg, Joachim H., Aldo Femia, Friedrich Hinterberger, Helmut Schütz, Stefan Bringezu, Christa Liedtke, and Friedrich Schmidt-Bleek. 1999. Material Flow-Based Indicators in Environmental Reporting. Copenhagen: European Environment Agency, vol. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Spear, Roger. 2001. El balance social en la economía social: Enfoques y problemática. CIRIEC-España, Revista de Economía Pública, Social y Cooperativa, 9–24. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/174/17403902.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Stiglitz, Joseph. E., Amartya Sen, and Jean-Paul Fitoussi. 2009. Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress. Available online: https://www.cbs.nl/-/media/imported/documents/2011/36/stiglitzsenfitoussireport_2009.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2023).

- Task Force on Social and Solidarity Economy (TFSSE)-United Nations Inter-Agency. 2014. Social and Solidarity Economy and the Challenge of Sustainable Development. A Position Paper by the United Nations Inter-Agency Task Force on Social and Solidarity Economy (TFSSE). June. Available online: https://knowledgehub.unsse.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/2014-EN-Social-and-Solidarity-Economy-and-the-Challenge-of-Sustainable-Development-UNTFSSE-Position-Paper.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Tovar, Élisabeth. 2016. The social and solidarity economy: The revival of an ideal? Regards Croisés sur L’économie 19: 160–72. Available online: https://shs.cairn.info/article/E_RCE_019_0160?lang=en (accessed on 30 August 2023).

- Ulanowicz, Robert E., Sally J. Goerner, Bernard Lietaer, and Rocio Gomez. 2009. Quantifying sustainability: Resilience, efficiency, and the return of information theory. Ecological Complexity 9: 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. 2015. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (A/RES/70/1). June 8. Available online: https://undocs.org/en/A/RES/70/1 (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Utting, Peter. 2014. Raising the Visibility of Social and Solidarity Economy in the United Nations System. The Reader. Social and Solidarity Economy: Towards Inclusive and Sustainable Development. pp. 145–64. Available online: http://base.socioeco.org/docs/14-raising-the-visibility-of-social-and-solidarity-economy-in-the-united-nations-system.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Van Den Berk-Clark, Carissa, and Loretta Pyles. 2011. Deconstructing neoliberal community development approaches and a case for the solidarity economy. Journal of Progressive Human Services 23: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieta, Marcelo. 2020. Workers’ Self-Management in Argentina: Contesting Neo-Liberalism by Occupying Companies, Creating Cooperatives, and Recuperating Autogestión. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalba-Eguiluz, Unai, Catalina González-Jamett, and Marlyne Sahakian. 2020. Complementariedades entre economía social y solidaria y economía circular: Estudios de caso en el País Vasco y Suiza Occidental. Cuadernos de Trabajo Hegoa, (83). Hegoa, Instituto de Estudios sobre Desarrollo y Cooperación Internacional, Universidad del País Vasco/Euskal Herriko Unibertsitatea (UPV/EHU): Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/347522493 (accessed on 14 October 2023).

- Vuotto, Mirta. 2011. La contribución de la investigación a las innovaciones: El caso de las organizaciones de economía solidaria. In Innovación y Economía Social y Solidaria: Retos y Aprendizajes de una Gestión Diferenciada. Edited by Jorge Dá Sa, Mirta Vuotto, Miguel Ángel Alarcón and Juan Fernando Álvarez R. Barranquilla: Inversiones Ibarra Garrito LTDA, pp. 159–79. Available online: https://base.socioeco.org/docs/innovacion_y_economia_social_y_solidaria..pdf (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Wackernagel, Mathis. 2001. Nuestra Huella Ecológica: Reduciendo el Impacto Humano Sobre la Tierra. Santiago: LOM Ediciones. Available online: https://journals.openedition.org/polis/pdf/7216 (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Waring, Marilyn. 1999. Counting for Nothing: What Men Value and What Women Are Worth. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Westall, Andrea. 2001. Value-Led Market-Driven: Social Enterprise Solutions to Public Policy Goals. London: Institute for Public Policy Research. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, M. J., J. W. Emerson, D. C. Esty, A. de Sherbinin, and Z. A. Wendling. 2022. 2022 Environmental Performance Index Results. New Haven: Yale Center for Environmental Law & Policy. Available online: https://bvearmb.do/handle/123456789/2828 (accessed on 23 November 2023).

- World Commission on Environment and Development. 1987. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future. Document A/42/427. Available online: http://www.un-documents.net/wced-ocf.htm (accessed on 24 November 2023).

- Yi, Ilcheong, Samuel Bruelisauer, Gabriel Salathe-Beaulieu, and Martina Piras. 2019. Implementing the Sustainable Development Goals: What role for Social and Solidarity Economy? Paper presented at the UNTFSSE Knowledge Hub for the SDGs, Geneva, Switzerland; Available online: https://knowledgehub.unsse.org/knowledge-hub/conference-summary (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Zurbano Irizar, Mikel. 2008. Gobernanza e innovación social: El caso de las políticas públicas en materia de ciencia y tecnología en Euskadi. CIRIEC-España, Revista de Economía Pública, Social y Cooperativa 60: 73–93. Available online: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=17406004 (accessed on 20 January 2024).

| Dimension | Indicator Questions | Criteria/Description |

|---|---|---|

| Participatory Governance of Companies | Is there financial independence (not relying on a single source of funding)? | (A) A high level of autonomy; social enterprises created by a group of people may also depend on public subsidies, but are not managed, either directly or indirectly, by public authorities or other organizations (federations, private companies, etc.). |

| Is the organization managed democratically (one person, one vote)? | (B) Decision-making power not based on capital ownership; this criterion generally refers to the “one member, one vote” principle, or at least to a decision-making process in which voting power is not distributed according to capital shares in the governing body. | |

| Are there democratic structures and processes that allow people to participate in decision-making at all levels (founders, producers, users and investors)? | (C) A participatory character; involving several parties affected by the activity; representation and participation of users or clients, the influence of several actors in decision-making and participatory management are often important characteristics of social enterprises. In many cases, one of the objectives of social enterprises is to promote democracy at local level through economic activity. |

| Indicator | Indicator Function | Sustainability from Each Indicator | According to (Savall Vercher 2021) Based on Quebec’s Experience |

|---|---|---|---|

| Governance | This indicator refers to progress in terms of consultation, agreement, partnership, recognition of the parties involved, deliberative and direct democracy. | Sustainability relates to the capacity of SI processes to maintain and improve long-term governance relationships. This includes continuity in the mechanisms of consultation, partnership and deliberative democracy that were initially established as part of SI. | SI implies changes in governance as it opens up processes to the participation of multiple agents and a greater degree of deliberative and direct democracy. The process of SI promotes changes in governance, encourages the satisfaction of needs and improves participation, especially of excluded social groups. |

| Dimension | Sub-Dimensions | Indicator | Normalized Scoring |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Socioeconomic Dimension | 1.1 Equitable distribution, responsible reinvestment and accountability for surpluses | 1.1.1 Level of participation in decisions on the distribution of surpluses and satisfaction with transparency in accountability | 0.82 |

| 1.2 Promoting the reinvestment of surpluses in sustainable projects and activities | 1.2.1 Reinvestment in Sustainable Projects and Impact Assessment | 0.55 | |

| 1.3 Development of monitoring and evaluation tools to ensure accountability | 1.3.1 Monitoring and Satisfaction | 0.45 | |

| 1.4 Development of solid financial structures | 1.4.1 Training and Alliances | 0.4 | |

| 1.5 Creation of SSE financial circuits | 1.5.1 Promotion of Circuits | 0.274 | |

| 1.6 Development of organizations with social and environmental criteria | 1.6.1 Social and Environmental Criteria | 0.7 | |

| 1.7 Integration of economic processes in the Social Market | 1.7.1 Integration and Cooperation | 0.867 | |

| 1.8 Promotion of a culture of transparency and responsibility | 1.8.1 Organizational Culture | 0.4 | |

| Average = | 0.5576 | ||

| 2. Environmental Sustainability | 2.1 Socio–environmental sustainability (for agricultural, forestry or livestock practices) | 2.1.1 Degree of use of organic and ecological practices | 0.25 |

| 2.2 Impact on the local environment | 2.2.1 Implementation of Sustainable Practices | 0.34 | |

| 2.3 Impact on the local environment; Level of Knowledge and Training in Sustainable Practices | 2.3.1 Level of Knowledge and Training in Sustainable Practices | 0.902 | |

| 2.3.2 Impact on the local environment: Implementation of Sustainable Practices | 0.24 | ||

| 2.3.3 Participation in the Formulation of Environmental and Social Policies | 0.74 | ||

| 2.3.4 Implementation of Actions for Environmental Regeneration and Conservation | 0.25 | ||

| 2.3.5 Sustainable Management of Natural Resources and Biodiversity | 0.43 | ||

| 2.4 Ecological sustainability | 2.4.1 Collaboration and Equitable Exchange of Shared Resources | 0.67 | |

| Average = | 0.4777 | ||

| 3. Social Innovation and Cooperative Sustainability | 3.1 Social and community participation | 3.1.1 Participation in the development of regulations and policies | 0.83 |

| 3.1.2 Dissemination of proposals and results of the SSE | 0.0 | ||

| 3.1.3 Promotion of internal and external solidarity | 0.47 | ||

| 3.1.4 Generation of stable and quality employment | 0.0 | ||

| 3.1.5 Promotion of the conciliation between personal, family and work life | 0.0 | ||

| 3.2 Inter-cooperation with other actors (internal/external) | 3.2.1 Cooperation with the Public Sector | 0.67 | |

| 3.2.2 Connection with academia | 0.6 | ||

| 3.2.3 Participation with NODES | 0.0 | ||

| 3.2.4 Creation of New Economic Models | 0.41 | ||

| 3.2.5 Collective interests | 0.66 | ||

| 3.2.6 Social entrepreneurship, sustainability, financing | 0.54 | ||

| 3.3 Sustainability and Social Responsibility | 3.3.1 Commitment to environmental sustainability and organizational ethics | 0.61 | |

| 3.3.2 Intersectoral cooperation to address environmental and social challenges | 0.33 | ||

| 3.3.3 Participation and trust | 0.67 | ||

| 3.3.4 Integration in local networks and social movements | 0.48 | ||

| 3.3.5 Assignment of responsibilities for the collaboration | 0.47 | ||

| 3.4 Pluralism | 3.4.1 Inclusion of governance | 0.57 | |

| 3.4.2 Diversity of actors | 0.23 | ||

| 3.4.3 Intersectoral collaboration | 0.24 | ||

| 3.5 Access to Wealth/Capital (Based on Ridley-Duff’s (2015) Fairshare Model) | 3.5.1 Natural Capital (A) | 0.54 | |

| 3.5.2 Human Capital (B) | 0.64 | ||

| 3.5.3 Social Capital (C) | 0.41 | ||

| 3.5.4 Intellectual Capital (D) | 0.55 | ||

| 3.5.5 Manufactured Capital (E) | 0.65 | ||

| 3.5.6 Economic Capital (F) | 0.367 | ||

| Average = | 4.374 | ||

| 4. Democratic Governance | 4.1 Decent work | 4.1.1 Fair remuneration | 0.5 |

| 4.1.2 Respect for workers’ rights | 0.0 | ||

| 4.1.3 Social protection | 0.0 | ||

| 4.1.4 Justice | 0.16 | ||

| 4.2 Governance, participation and equity | 4.2.1 Inclusion in decision-making | 0.817 | |

| 4.2.2 Retirement plans | 0.0 | ||

| 4.2.3 Promotion of rights and opportunities | 0.67 | ||

| 4.3 Democratic participation and collective empowerment | 4.3.1 Structure of collective decision-making processes | 0.93 | |

| 4.3.2 Frequency and effectiveness of collective decisions | 0.73 | ||

| 4.3.3 Satisfaction with freedom of expression | 1.0 | ||

| 4.4 Democratic management; degree of responsible collective management | 4.4.1 Democratic management | 0.89 | |

| 4.4.2 Transparency and equity in decision-making | 0.87 | ||

| 4.4.3 Commitment and awareness among beneficiaries and service providers | 0.77 | ||

| 4.4.4 Management by civil community | 0.75 | ||

| 4.4.5 Participation of partners in decision-making processes | 0.77 | ||

| 4.4.6 Existence of clear and transparent rules | 0.89 | ||

| 4.5 Self-management, independence and autonomy | 4.5.1 Financial autonomy | 0.38 | |

| 4.5.2 Democratic Participation | 0.82 | ||

| 4.5.3 Solidarity and self-management | 0.92 | ||

| 4.5.4 Cooperating with the Environment | 0.407 | ||

| 4.5.5 Collaboration Networks | 0.433 | ||

| 4.5.6 Evaluation of Cooperation and Social Commitment | 0.34 | ||

| 4.6 Comprehensive and Sustainable Self-management | 4.6.1 Social management and accounting of activity (constitutive acts) | 0.93 | |

| 4.6.2 Reciprocity (Education/training) | 0.74 | ||

| 4.6.3 Transparency and distribution of surpluses and goods | 0.77 | ||

| Average = | 0.6194 | ||

| 5. Responsible Production and ethical commercialization | 5.1 Ethical review of production and processes | 5.1.1 Impact on Well-being | 0.69 |

| 5.1.2 Commitment to Stakeholders | 0.5 | ||

| 5.1.3 Environmental Sustainability | 0.57 | ||

| 5.1.4 Social Equity | 0.34 | ||

| 5.1.5 Business Ethics | 0.67 | ||

| 5.1.6 Commitment to the Environment | 0.825 | ||

| 5.1.7 Trust in the Environment | 0.67 | ||

| Average = | 0.6092 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Servin, J.L.; Hernández, A.O.; Andrade, M.L.; Vargas, R.R.; Mendez, N.L.; Rocha, K.O. Indicator Development for Measuring Social Solidarity Economy. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 329. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060329

Servin JL, Hernández AO, Andrade ML, Vargas RR, Mendez NL, Rocha KO. Indicator Development for Measuring Social Solidarity Economy. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(6):329. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060329

Chicago/Turabian StyleServin, Joe Luis, Alejandro Ortega Hernández, Marilu León Andrade, Rocío Rosas Vargas, Naxeai Luna Mendez, and Karina Orozco Rocha. 2025. "Indicator Development for Measuring Social Solidarity Economy" Social Sciences 14, no. 6: 329. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060329

APA StyleServin, J. L., Hernández, A. O., Andrade, M. L., Vargas, R. R., Mendez, N. L., & Rocha, K. O. (2025). Indicator Development for Measuring Social Solidarity Economy. Social Sciences, 14(6), 329. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14060329