1. Introduction

In the Netherlands, the number of vacancies is currently greater than the number of unemployed (114 vacancies for every 100 unemployed) (

Centraal Bureau voor Statistiek [Statistics Netherlands] 2023). In theory, there should be enough vacancies for everyone searching for a job. However, a particular group of young adults in vulnerable positions experience barriers to taking their first career step (

Neuman et al., forthcoming). Following

Bijl et al. (

2015), we define “young adults in vulnerable positions” as “young adults who experience limited room in the environment in which they participate to shape their lives in ways they want and overcome setbacks with that”. The young adults we focus on in this study face challenges in building their careers, as part of the overall challenge of constructing themselves and shaping their lives (

Neuman et al., forthcoming). Shaping their careers is integral to their self-construction, which aligns with how we see what some career development literature refers to as career agency.

Career agency is a central concept in career development and is interpreted differently in the literature. Human capital theories (e.g.,

David and Lopez 2001;

Nafukho et al. 2004) suggest that knowledge, skills, and career agency can lead to greater success in the competitive labor market (

Ng et al. 2005) and are essential for maintaining one’s position during market changes (

Arthur et al. 2005). These theories often emphasize the importance of people’s competencies, which may highlight deficiencies when focusing on young adults in vulnerable positions. This perspective appears to overlook the potential for career agency to be developed over time and the desire of young adults to develop their careers (

Neuman et al., forthcoming). Existing career theories that adopt a developmental lens offer important insight (e.g.,

Kuijpers 2003). However, these lenses do not fully capture the ongoing, dynamic, and contextually shaped nature of career agency. Therefore, theoretical approaches from a contextual and developmental perspective are more suitable for understanding agency development among young adults facing vulnerabilities in the labor market.

Cultural-Historical Activity Theory (CHAT) is a framework for understanding how people learn, work, and develop through activities shaped by the dynamic relationship between persons and their social, cultural, and historical contexts. CHAT emphasizes that human development and action are not isolated, but part of a larger system involving tools, rules, community, and shared goals (

Engeström 1987). CHAT sees contradictions within and between persons and systems not as problems, but as a starting point for development and change (

Vygotsky 1978). Even though the term agency is not always used explicitly, the concept of agency has always been central to CHAT since the theory focuses on how persons transform their activities (

Hopwood 2022). Because of this history, CHAT provides a detailed conceptualization of agency development. It offers a framework for understanding how agency emerges through the complex relationships between people’s development and the (also developing) environments in which they participate. However, there is limited research on career agency development from a CHAT perspective. Therefore, this study also examines CHAT’s potential to enhance our understanding of career agency development. We aim to present a developmental perspective highlighting the potential for growth and adaptation among young adults within a challenging labor market and with demanding life circumstances.

Drawing on CHAT, we explore young adults’ agency development as an emergent and dynamic process. Young adults in vulnerable positions navigating their career paths often face contradictions and situations in which their motives, goals, or environments conflict, complicating decision making. These contradictions manifest in various forms; some arise between personal motives and the perceived characteristics of external environments, while others result from conflicting intrapersonal motives.

Building on the concepts of contradictions as conceptualized in CHAT, we aim to understand what contradictions young adults in vulnerable positions experience when they enter the labor market and how they deal with them.

2. Conceptual Framework

2.1. Career Agency

These latter career development perspectives are valuable because they acknowledge the environments of young adults and that career agency can emerge even when it is not immediately visible. This means that agency can already be set in motion within a person as an internal process of imagining an action and setting an intention, even when no outward action is visible. While whole-life and emergent career agency theories acknowledge that agency can develop in complex contexts, they do not fully explain how this development unfolds. This highlights the need for a perspective that captures the dynamic processes through which career agency emerges.

We build on the notion from career agency theories that agency can be set in motion internally as an imaginative and intentional process, even without outward action, while also recognizing that existing whole-life and emergent theories do not fully capture the dynamic, context-dependent processes through which agency unfolds.

2.2. Perspectives on Agency

Various understandings of agency conceptualize agency as an inherent trait or a static “sense” of control (

Moore 2016). Moving away from agency as merely a “sense” and toward agency as action within a social framework, we can better understand and support these young adults in identifying steps and creating change.

Hopwood (

2022) critiques such views as insufficient to address the practical realities that people, in our study, young adults, face. When agency is limited to personal traits or framed as a state or sense detached from material and social circumstances, the risk exists that social structures are reinforced that contribute to vulnerabilities rather than empowering persons to reshape their situations actively. These conceptualizations place the ‘responsibility’ of agency solely on the person to overcome challenges and expect social structures and practices to remain as they are. Exploring agency as a “sense of control” reflects the common psychological interpretation of agency as a person’s feeling of being in charge (

Frith 2017;

Moore 2016). However, this sense can be misleading and does not always align with real-world conditions. For young adults facing inequalities, this inward-looking perspective on agency could risk reinforcing a sense of responsibility in situations beyond their control.

A view of agency as a phenomenon arising from the interaction between people and social structures emphasizes the interconnectedness of personal action and societal contexts (

Archer 1996,

2003;

Giddens 1984). However, while understanding the development of agency as the interplay between structural forces and agency is compelling, it does not explain how this interaction unfolds in practice and does not provide a complete picture of people’s often dire and complex realities or how someone could change a complex situation (

Engeström and Sannino 2017).

To summarize, existing views of career agency often frame it as a static trait or a sense of control, which risks overlooking the complex realities that young adults face, or portray agency as an interaction between an individual and structures. These perspectives do not fully explain how agency develops in practice. We incorporate agency as an emerging phenomenon between a person and social structures. Furthermore, we are seeking a lens through which we can understand how this emergence unfolds.

2.3. Dialectical Contradictions

Our analyses, later discussed in the findings, show that young adults in vulnerable positions frequently experience contradicting expectations from different environments and what they want does not always align with their environment. Because of that, it is crucial to look at the contradictions and tensions that young adults in vulnerable positions experience in their social context to shift how we conceptualize agency, understand its emergence, and strengthen it. According to

Engeström and Sannino (

2011), contradictions manifest as conflicts, dilemmas, critical conflicts, and double binds.

Conflicts are disagreements or clashes between persons or groups. They are often on the surface and can be negotiated. For example, a young adult wants to pursue further education but faces pressure from their parents to start earning money. In this example, the young adult can try to solve this conflict through negotiation, compromise, or coming to a consensus. Critical conflicts occur when someone experiences deep internal contradictions. These tensions are often experienced as personal crises and can have a paralyzing effect. For example, a young adult feels torn between their passion for a creative career and the pressure to choose a stable, high-paying job. Critical conflicts can be a reason for persons to initiate intrapersonal change.

Dilemmas usually involve hesitation or contradictory statements between competing options. For example, a young adult receives two job offers, one close to their expertise and skills, but without the possibility for education and training. The other job offer is in a new and promising field with many educational and training opportunities, but it is an uncertain path because the company is young. The young adult can resolve this dilemma by a decision-making strategy, such as by making a pros and cons list. Double binds are complex, systemic contradictions that cannot be solved in the current structure. Often, both options have negative consequences. For example, young adults are told they need work experience to obtain a job but cannot gain experience without first having employment. At first, there seems to be no clear way out of this contradiction for young adults. The only way for them to resolve this double bind is to transform the system and create new possibilities that break through these contradictory demands.

This framework of contradictions helps define contradictions in career agency. It allows for identifying and understanding the contradictions young adults experience and analyzing their impact on agency development. In addition, it identifies incentives for change in double binds and critical conflicts because of conflicts of motives, which will be discussed in the next paragraph.

2.4. Double Stimulation

Agency development inherently emerges through engagement with the environment, fostering possibilities for change, for both the environment and the person. The principle of double stimulation (DS) (

Engeström and Sannino 2017;

Sannino 2015,

2022;

Vygotsky 1978,

1997) provides insight into the development and emergence of agency from contradictions. DS is a dynamic process in which persons encounter contradictions (first stimuli) and actively construct new means, tools, or strategies (second stimuli) to gain control over the situation, through engaging the contradictions, searching for new possibilities, and deliberately reorganizing activities. DS explains how persons navigate and attempt to resolve contradictions by providing insights on conflicting motives. A conflict of motives occurs when a person experiences two or more competing desires, goals, or values, making it difficult to act. This internal struggle can create hesitation, emotional tension, or even paralysis if no clear resolution is found.

DS describes two types of stimuli in this process. The first occurs when someone experiences a contradiction and becomes aware of their conflicting motives, as illustrated by the two examples of young adults in their work environments. The second stimulus is a resource, such as a tool or concept, that helps to open the zone of proximal development (

Vygotsky 1987), such as another perspective, which allows the young adult to imagine other possibilities to act. This could evoke the urge to engage in the environment and can activate their willpower to overcome conflicting motives, allowing persons to participate in that environment. DS thus provides a lens through which we can describe what young adults encounter when they experience contradictions. These contradictions can induce motives to act but also paralyze them (experiencing the first stimulus), when they can or cannot envision what might help them to break through the contradiction (searching for a second stimulus).

DS starts with becoming aware of an often historically rooted contradiction that may evoke a paralyzing effect. For example, a young adult struggles with the decision to start working because she does not want to leave her children. Her hesitation is deeply rooted in her experience; at 13, she was left behind when her mother migrated abroad. The experience of growing up without her mother’s presence shaped her meaning of care, attachment, and absence. Now, experiencing having to choose between work and family, she experiences a conflict of motives.

Conflicts of motives can arise in the intertwined relationship between a person and their environment. For instance, a young adult had an experience in a workplace in which he worked under two supervisors. One supervisor treated him kindly and fairly, while the other often became angry with him for reasons that seemed unjustified to him. His interactions with the second supervisor and the uncertainty accompanying this interaction frequently led the young adult to experience a conflict of motives. Conflicting motives can also arise within a person regarding their environment, for example, a young adult who notices that their coworkers often do not follow plans. This bothers her, prompting her to address the issue during a staff meeting. In this situation, something that appears to be the status quo (deviating from the plan) evokes a conflict of motives and the young adult’s willpower to change her work environment. When a conflict of motives arises, the volition to resolve it can emerge, and it is helpful to try to make sense of these motives. Sometimes, individuals can achieve this independently; other times, they require assistance from someone or something. In the latter situation, gaining insight into their conflicting motives can reveal opportunities for clarity and potential courses of action. With or without help, young adults attempt to break through their conflicting motives. The breakthrough starts when a young adult has the will to act. At that moment, the young adult’s development is set in motion.

Double stimulation provides insight into the process through which agency develops. By explicating the first stimulus and creating a meaningful second stimulus, young adults can adopt new ways of acting, reshaping their environment and role. A mentor can play a crucial role in fostering agency by providing the second stimulus in a double stimulation process. This means that mentors do more than offer advice; they actively assist young adults in recognizing constraints, reframing challenges, and taking empowered action to reshape their circumstances. This is what we refer to as a formative intervention. Formative interventions support young adults in reinterpreting their situation and accessing new ways of thinking or acting.

A breakthrough represents a moment when young adults shift their way of thinking, acting, and giving meaning to their experiences. The meaning of their earlier experiences evolves to accommodate a broader sense of possibility, allowing them to engage more fully with their environments and pursue meaningful change.

2.5. Research Questions

Building on the conceptual framework, we formulated the following specific research questions that guided our analyses:

What significant experiences do young adults encounter that contribute to or hinder the development of career agency while trying to find sustainable, meaningful work?

How can we understand the contradictions that emerge from these significant experiences?

How do young adults in vulnerable positions navigate challenges while striving for sustainable and meaningful work?

4. Results

We start by presenting one exemplary participant to illustrate the contradictions young adults experience and how they navigate them. This participant was selected for the richness of their experience, as it allowed us to illustrate nearly every theme in our results, offering a comprehensive view of how they manifest and affect career agency development. While this participant serves as the primary focus, the other participants will support the findings.

4.1. Sophie

Sophie is a 21-year-old woman living in transitional housing with support. She has a boyfriend, and they live together. Sophie and her boyfriend want to have children; however, that is not possible in their current situation. They need to find their own apartment before they can start a family. Sophie texts her mother daily, describing their relationship as “two peas in a pod”. She has a sister with whom she has no contact and a brother who is in residential care. Sophie’s mother developed a mental illness and was hospitalized. Due to personal circumstances, Sophie and her father have not been in touch since she was a child. After the death of her stepfather, Sophie felt compelled to reconnect with her biological father. She has set boundaries with him: they only communicate via text, she does not want any drama, and their conversations cannot involve her mother.

Sophie no longer has friends. Not long ago, she had a group of friends, but she realized they were not interested in her and only visited to empty her fridge and drink excessively. Sophie also had a friend who lived a few hours away. They talked frequently about various topics. He wanted to be more than just friends, but she felt the distance was too great, so she was uninterested. One day, he felt ill. After a few days, he started to recover and went to a grocery store, but he collapsed while shopping and passed away.

Sophie has been in poor health since she was a child. Because of her poor health, she needed a diaphragm surgery which, unfortunately, affected her lungs. After a fall from the stairs, she needed an ear surgery, and this left her nearly deaf in one ear. This injury caused a small hole behind her ear, and later, doctors discovered a virus there, necessitating surgery. This led to lasting balance issues, as the virus had impacted her inner ear. She continues to receive physiotherapy to recover from this.

Due to the illness that Sophie dealt with as a child, she attended special daycare as a child and later alternated between special and regular education. At school, she faced bullying for wearing a diaper for medical reasons and for being perceived as overly attached to her mother, who always dropped her off. The bullying continued at her next school, where a boy who practiced karate even pushed her off a climbing frame. When the school refused to act, her mother kept her at home for an extended period. Even after transferring to special education, the bullying persisted, although it eventually diminished.

She later attended a vocational school, where she struggled with illness and continued to face bullying. Due to her health, internships were challenging, but she completed one at a veterinary clinic. She then joined an alternative internship program in which students engaged in tasks like candle-making and cleaning. Her health issues resurfaced, preventing her from finishing school, though she did obtain certificates in safety, health, and environmental practices, as well as cleaning. Missing out on other qualifications, such as cooking and first aid, was disappointing.

Despite these challenges, she was allowed to take her exams in a separate room and successfully passed them. At the graduation ceremony, it was decided that she would continue her vocational education. She enrolled in a logistics program, but the long travel hours and ongoing illness made it difficult to finish her studies. To this date, Sophie has not gained relevant work experience. She has tried several jobs in the hospitality industry, but none lasted long. Each time, she either felt exploited, struggled with a sense of rejection, or found it too hard to sustain the work due to her poor health. She also attempted a day program, but it did not match how she viewed herself. Sophie saw herself as capable of holding a regular job and could not identify with people participating in day programs, making it an unsuitable choice.

4.2. Experiences of and Challenges from Other Young Adults

In this part of Sophie’s life story, we identify earlier experiences and present challenges that may have influenced the development of her career agency. Sophie faces family issues, such as her mother’s mental illness, the death of her stepfather, and the prolonged absence of her father. Additionally, we note her friendships: Sophie has almost no friends and has faced dysfunctional relationships. Her living situations include transitional housing with support, and her brother is in residential care. Sophie also confronts physical health issues like chronic illness and pain.

We identified similar past experiences and current challenges shared by other young adults. For instance, in fourteen other participants, young adults deal with various family issues. Significant experiences encompass strained or absent relationships with parents and siblings, parental divorce, parental cases of imprisonment or mental illness, experiences of abuse or neglect, and the loss of one or both parents. Six of the twenty-five young adults also encountered challenges with friendships. Their experiences included social isolation, dysfunctional friendships, and influences from peers that led them to commit fraud or engage in other misdemeanors. We identified instability in and issues with the living situations of thirteen young adults. These young adults encountered unstable housing arrangements, ranging from living in foster homes or youth facilities to experiencing homelessness. They also faced environmental challenges, such as residing in deprived or unsafe neighborhoods. Additionally, their experiences included eviction from their homes or supported living programs, residing in Salvation Army housing, squatting in buildings, being on the run, and living in a car. Sixteen young adults reported unsafe or unsuitable learning conditions, a lack of guidance, and dropping out of educational settings. They also faced bullying, struggled to meet school standards, encountered learning challenges, felt pressured to learn in ways that did not suit them, were frequently absent, did not complete their education, and lacked adequate schooling.

Thirteen young adults shared their health concerns. They listed a wide range of mental, emotional, and physical health issues, including mental illnesses such as PTSD, anxiety disorders, depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, difficulties with emotion regulation, and hallucinations. Additionally, some young adults indicated being on the spectrum, including having autism or ADHD. They also mentioned physical conditions like chronic pain, birth-related brain damage, and developmental disorders. Variations in the earlier experiences of and challenges identified among four young adults included their engagement in misdemeanors. These experiences involved jail time, community service, drug dealing, and gang involvement. Similarly, five young adults acknowledged dealing with a drug addiction. Four young adults discuss self-perception, including low self-esteem, feelings of inadequacy or unworthiness, and self-identification with negative labels, which can hinder their ability to take steps toward a meaningful career. Similarly, four other young adults express challenging traits they see in themselves, such as difficulties with independence, trust, and emotional regulation, as well as conflict-seeking, addiction, and obsessive or evasive tendencies. Two young adults discussed their financial situation. They were in debt and unable to apply for social benefits.

Like Sophie, all young adults from this study have experienced challenges in their lives and career development at some point. These challenges include a lack of relevant work experience, workplace conflicts, insufficient guidance, overwhelming workloads, and a poor work/life balance. We have identified small or diminishing networks among young adults. This applies to both networks that can provide support and networks that young adults could use to find meaningful work. Seven young adults noted limited workforce access to positive role models.

4.3. Four Types of Contradictions

The experiences and challenges outlined in the previous paragraph are unsurprising; instead, they align with our initial expectations that young adults in vulnerable situations face multiple problems. Consequently, we explored these dynamics further to understand how these difficulties interact, delving into their experiences and challenges. Sophie’s story and our analysis of twenty-five narratives from young adults in vulnerable situations revealed that they often encounter contradictions arising from the interplay of their self-perceptions, past experiences, and environments. These contradictions frequently hinder their ability to recognize opportunities for action, which can be paralyzing. Our analysis identified four types of contradictions (see

Table 2), which we will discuss in the following section.

The first contradiction (tied between a motive and one antagonistic environment) emerges from the interplay between a young adult and their environment. Often, this contradiction arises from an earlier experience that conflicts with a current challenge. Sophie encountered this type of contradiction when she finally found a company where she wanted to work. However, there was a 7-year waiting list for this company. In her earlier experiences, there are multiple examples of times at her school and work when the workload was overwhelming for her, and due to her frequent illnesses, she was unable to continue. In this situation, Sophie was clear about her motives. She discovered a company that aligned with her work capacity and the type of work she enjoys (selecting clothes for a second-hand shop) and desired to work there. Nonetheless, at that moment, there were no opportunities within this company, which paralyzed Sophie. She experienced a contradiction between knowing what she wanted and feeling uncertain about how she could achieve it.

In summary, this type of contradiction emerges when a young adult does or does not want something. In other words, the young adult is clear about their motives. However, they see no opportunities for action, or their environment provides no possibilities for change. A similar situation appears in another young adult’s story; he wanted to complete his education but was compelled to leave school, creating a conflict between his goal and reality. Two young adults did not wish to travel long distances for their education, but their schools were farther away than anticipated, contradicting their preference for a short commute.

Six young adults discussed their school experiences. They recognized from past situations that they needed specific guidance from a mentor or teacher, and that support was missing. The young adults had a clear need, but their surroundings did not meet it. One young adult imagined himself as a soccer coach. However, he lost interest upon realizing that the required tasks entailed not only soccer and coaching but also training science, anatomy, language, and mathematics. Similarly, six young adults initially thought their school and class would offer a safe and supportive learning environment. Yet, they later found their class harsh and felt they were not receiving the expected guidance.

Another young adult, for example, believed he did not need a diploma to succeed in society. A different young adult assumed that the municipality would continue covering his housing costs, but when the payments stopped, he was left uncertain about how to finance his living situation. In both situations, their expectations clashed with reality, leading to contradictions. One young adult experienced his emotions intensely and expressed them vividly, which was often not accepted by those around him. In other situations, he reacted from trauma and struggled to control his responses, resulting in conflicting scenarios.

The second contradiction (tied between a motive and two antagonistic environments) emerges from the interplay between multiple environments, evoking a contradiction for the young adult. In this type of contradiction, two or more perceptions of environments of the young adult conflict; for instance, a situation in their private life demands significant attention, causing the young adult to pay less attention to their work context. At the same time, the young adult still wants to concentrate fully on their work. We observed this contradiction with Sophie. Her work situation clashed with her personal life while she was on vacation. Although she informed her employer of her unavailability well in advance, they still called her to come in. This placed her in a difficult position and created considerable stress. Nevertheless, her motive was clear; despite the risk of being fired, she refused to return to work.

Another young adult wanted to complete his education while he was younger. However, his home situation was troubled, causing him to miss too many classes. In this example, he was clear about his motive: finishing his education. Yet, his conflicting circumstances evoked mixed feelings about wanting to complete his education but not knowing how to achieve it. A different young adult faced a similar situation; he was involved in a lawsuit that prevented him from obtaining a declaration of good conduct, and therefore, he could not finish his education. He was also clear about his motive; he wanted to complete his education. However, this was not possible due to the conflicting environments, the lawsuit, his inability to obtain a declaration of good conduct, and the school. Another example came from a young adult who wanted to apply for social benefits but needed a home, which he did not have. His motive was clear: he wanted to receive social benefits. The conflicting environments involved the pursuit of social benefits and his lack of housing, which led him into a negative spiral he could not escape.

The third contradiction (tied between two motives in one environment) arises from a specific environment, similar to contradiction 1. However, this environment creates a conflict of motives that leaves young adults uncertain about their motives. This contradiction is more complicated and paralyzing because the young adults must resolve their confusion before considering possible actions.

When Sophie was in school, she often struggled to complete an internship due to frequent illnesses. She faced conflicting motives: on one hand, she wanted to finish the internship and her education, but on the other hand, when she felt unwell, she wished to stay home. Eventually, she decided to pursue an internship at a veterinarian. The internship environment created a conflict of motives between her desire to complete the internship and her struggle with not feeling well and wanting to stay home. This conflict was further intensified by her previous experiences of illness that had prevented her from finishing an internship in the past.

Another young adult worked with his nephew at a construction company. At one point, he considered quitting because he and his cousin, the company’s owner, did not always agree on business matters. However, he did not want to leave; he wanted to stay to please his nephew. The context of the construction company created a conflict of motives that paralyzed him. A different young adult experienced excitement and fear when meeting a new mentor who would help him get his life back on track. Similarly, two young adults struggled with conflicting emotions about their environments, feeling both a desire to ask questions at work and hesitation, eagerness, and anxiety about visiting a company alone. In another young adult’s situation, we identified various internal conflicts. She struggled with simultaneous desires to advance in life and fears of inadequacy, whether in her internship, dance classes, or career planning. A young adult from the study faced a dilemma between accepting her foster parents’ encouragement to become independent and feeling uncertain about how to achieve it. A young adult grappled with the decision to release his music, torn between the desire to share it and doubts about its readiness. A different young adult felt both happiness and shame about receiving social benefits. In contrast, another young adult was overwhelmed by worries about building a future, fearing it might remain unattainable.

The fourth contradiction (tied between motives in different environments) emerges from two or more environments, like contradiction 2, and evokes a conflict of motives, like contradiction 3. However, this contradiction is different because it has conflicting motives and different environments. Sophie’s fourth type of contradiction occurred before her holiday (described in contradiction 2). Her workplace frequently required her to work longer hours from the start, which conflicted with her circumstances at home. She had a set curfew in her residential group, and her boyfriend also expressed concerns about her late shifts. Her motives remained in conflict; she wanted to keep working but did not want to stay longer than scheduled. This had a paralyzing effect on her. On the one hand, Sophie wanted to keep working because, in her earlier experiences, she knew she could not always sustain her job. On the other hand, she felt she was taken for granted and not taken seriously.

A young mother of two children also experienced this type of contradiction; in the interview, she mentioned having worked at a factory for a while. At that time, her job conflicted with caring for her children. The two opposing environments (the factory and parenting) created conflicting motives. On one hand, this young mother wanted to work. She needed the money and felt stressed when she was not employed, but she also felt guilty while working because she believed she was not taking good care of her children. This belief stems from her experience. When she was young, her mother immigrated to the Netherlands before she did. She felt abandoned by this and was determined to prevent her children from experiencing the same feeling at all costs.

Another young adult faced a contradiction between finishing school and the responsibility of helping at home due to his mother’s injury. Similarly, a young adult struggled with completing her education amidst distractions and challenges from her family, romantic relationship, and personal life, questioning her perseverance. A different young adult faced loyalty conflicts between cooperating with the police and remaining loyal to his gang, highlighting a choice between his current life and the possibility of a more stable future. Another young adult was torn between finishing his near-completed vocational training and pursuing a new one that better aligned with his interests. An example from a young adult was that his school attendance declined after his father’s death, creating tension between fulfilling his mandatory education requirements and coping with his grief.

These analyses identify contradictions in young adults’ experiences stemming from their participation across different contexts. These contradictions align with

Engeström and Sannino’s (

2011) manifested contradictions. They reflect tensions between expectations, roles, and personal agency, leading to conflicting motives that can be paralyzing. Many contradictions could be described as critical conflicts and double binds rather than dilemmas or conflicts. Critical contradictions occur when individuals experience a deep internal struggle that prevents them from acting, often accompanied by paralysis. This aligns with the finding that young adults, when experiencing a contradiction, often feel stuck, uncertain, or unable to see possibilities for action. Some contradictions resemble double binds, which are even more complicated to solve than critical conflicts. A double bind occurs when any available action leads to negative consequences, making meaningful agency impossible.

4.4. Young Adults Dealing with Contradictions

The following section marks the beginning of our exploration into how young adults navigate and deal with their contradictions. Examples from Sophie and other young adults illustrate contradictions three and four, which are tied between two motives in one environment and tied between motives in different environments. These often paralyze them, preventing them from perceiving any possibility for action. Thus, young adults do not know how to manage these contradictions. However, Sophie and the others also experienced ways to break through contradictions, which brought their development back into motion. Also, all the young adults in the study displayed a clear willingness to advance in life and work. They expressed their motivation through examples of efforts to break through contradictions.

The data provided several examples of young adults who imagined a future for themselves, including a job, a house, or travel. All the young adults referenced these visions when discussing their intended next steps, using phrases like, “To achieve this picture I am imagining, I plan to do this first”. Every action taken by the young adults in this study stemmed from an initial phase of imaginative thought, a mental process in which they envisioned a possible course of action before engaging with their environment. This imagination was influenced by their past experiences, perceived opportunities, and the contradictions they faced in their surroundings. For some young adults, imagination served as a tool for envisioning potential paths forward despite obstacles. They visualized themselves in new roles, relationships, or situations that aligned with their goals. However, for others, their imagination was clouded by previous failures, external constraints, or a perceived lack of possibilities, leading to hesitation, self-doubt, or paralysis. In the previously mentioned example of Sophie in contradiction three (tied between two motives in one environment), her love for animals became a tool to complete her internship. Whenever she felt tempted not to go, she would visualize the animals she could help that day. This visualization was more potent than her desire to stay home, encouraging Sophie to go to the veterinarian even when she did not feel well.

The following examples of how young adults dealt with contradictions seem intentional. One young adult took the initiative to visit multiple companies in search of opportunities, actively engaging with employers rather than waiting for guidance. Another consciously decided to restart their education from the beginning, recognizing the need for a fresh start to achieve their goals. A different young adult independently gathered information about potential further studies, carefully weighing their options before enrolling in a new program despite discouragement from others who claimed they would fail. This decision highlights their determination and willingness to challenge external doubts. Another young adult took proactive steps toward skill development by enrolling in a specialized course and purchasing a GoPro to document their learning process, demonstrating commitment and resourcefulness. Similarly, one young adult deliberately chose to restart their education, taking ownership of their learning path rather than following the expected route. One young adult proposed an alternative way to complete their education, showing a strong sense of self-advocacy and problem solving.

These examples demonstrate young adults advocating for themselves and actively shaping their futures. They also illustrate how young adults navigate challenges through intentional decisions that align with their personal and professional aspirations. We describe a young adult’s independent action taken without guidance or support from a mentor or significant other as a formative intravention. Even when independently initiated, this action represents an interplay with the (imagined) environment, as it reflects the young adult’s process of considering environmental influences. These moments signify substantial breakthroughs, evoking a shift from external dependence to self-directed action. In these instances, young adults navigate contradictions in their environment and take steps toward change despite uncertainty or obstacles. Such interventions do not merely lead to different outcomes; they often reshape how young adults think, act, and give meaning to their experiences. A breakthrough frequently challenges their previous self-perceptions and reveals new possibilities for action. For example, after breaking through her conflicting motives and going to the veterinarian daily, Sophie began to see herself as capable of completing the internship. This reframing of her experience was crucial in Sophie’s situation because it fostered her sense of future possibilities.

Another example is one of our participants, Liam. When he accepted help from a mentor at his shelter, a learning process began, and we saw Liam breaking through multiple contradictions, discovering new meanings in his experiences. Overcoming these contradictions fosters Liam’s overall development. Over time, he has reinvented himself and undergone profound changes. For instance, he now approaches situations differently and sees more possibilities for action. He reflects on his past experiences in a new light, recognizing their positive impact on him; he has gained greater control over his emotions in various situations before accepting help from this particular mentor.

Imagination and the formative intraventions (intentional decisions) that follow from imagination highlight the emergent nature of agency. Each experienced breakthrough strengthens their potential to navigate future contradictions in increasingly complex situations.

5. Conclusions

In search of what significant experiences young adults encounter that contribute to or hinder the development of their career agency while trying to find sustainable, meaningful work (research question 1), we found that the development of career agency among young adults was deeply influenced by a complex relationality of personal and contextual experiences. The data revealed that many participants faced significant difficulties, including family instability, social isolation, housing issues, interrupted education, health issues, negative self-perceptions, diminished networks, limited access to role models, and difficulties engaging in work environments.

To understand the contradictions that emerge from these significant experiences (research question 2), this article discussed the experiences and challenges young adults encounter. We looked deeper into the impact of the interaction between the young adults and their experiences. The data were examined through the lens of manifested contradictions and double stimulation (DS) (

Engeström and Sannino 2011;

Engeström and Sannino 2017;

Sannino 2015). Through these perspectives, we identified and elaborated on four types of contradictions experienced by young adults. The first type involves a conflict in which young adults are aware of their desires but encounter obstacles that prevent them from taking action. The second type includes a conflict stemming from the experience of multiple environments, such as challenges at home that interfere with professional challenges. Ambiguous motives characterize the third type of conflict and involve a perceived challenge within an environment. The fourth type involves both perceived conflicting environments and ambiguous motives. Drawing from participants’ experiences, these insights provide a nuanced understanding of young adults’ challenges in building sustainable careers.

To examine how young adults in vulnerable positions navigate challenges while striving for sustainable and meaningful work (research question 3), this study showed the dynamics of the interplay between young adults and their environments, which evokes the different types of contradictions and their impact on career development. Contradictions often paralyze young adults, causing them to feel unable to act due to conflicting motives. However, young adults can self-initiate change through formative intraventions, as demonstrated by Sophie, who harnessed her love for animals to complete her internship. With this, the study highlights that overcoming contradictions through intraventions can lead to significant changes in thinking, acting, and giving meaning, which we see as agency, thus fostering career agency development.

This study highlights the importance of further research into the role of mentors, and other significant others, in supporting young adults through critical moments when their development stalls. Further research could explore how mentors can actively help them break through the identified contradictions, adjust their way of thinking, act, and find meaning.

6. Discussion

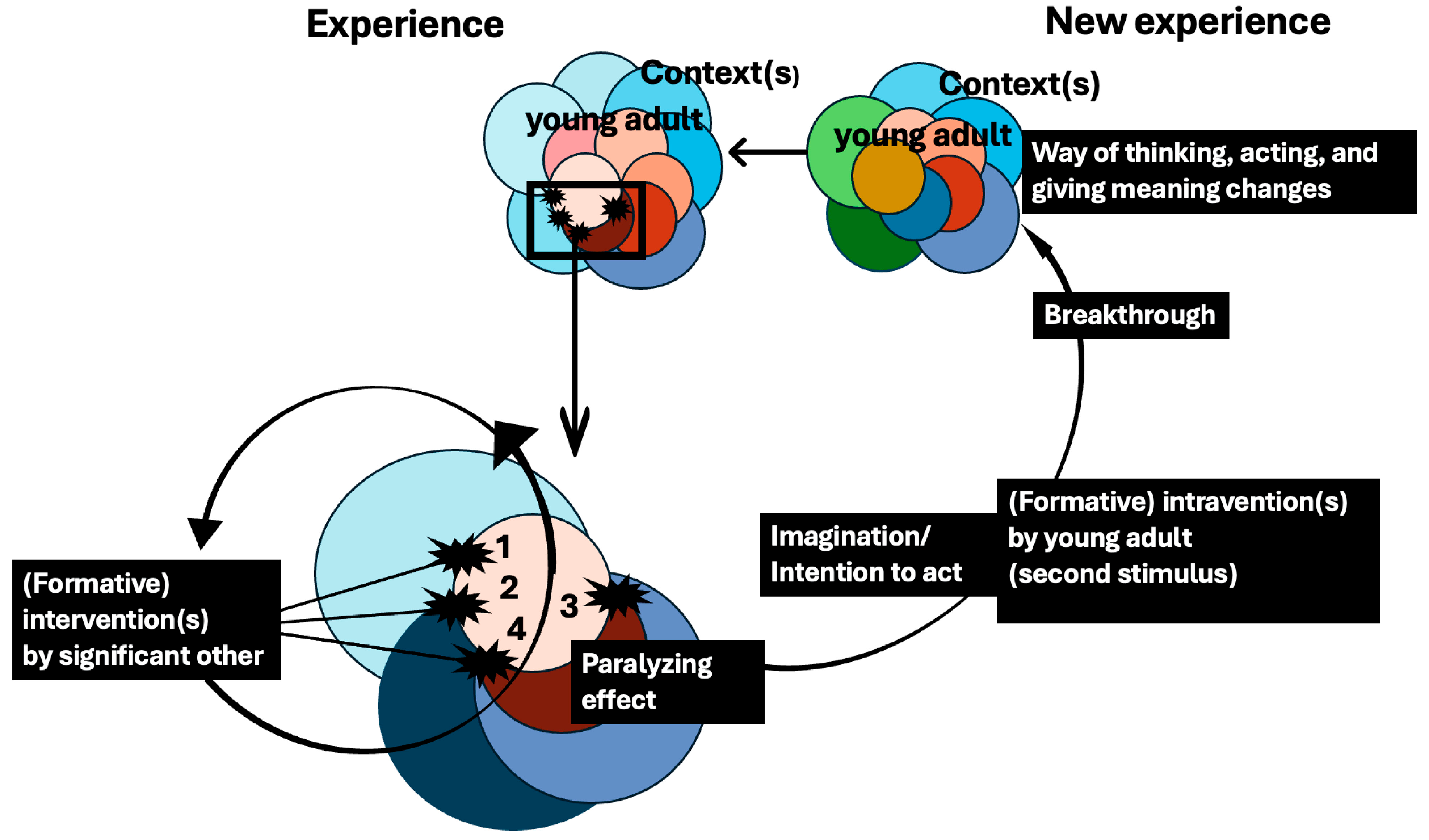

The findings of this study reveal that the interplay between self-perceptions and often challenging circumstances shapes the development of career agency among young adults in vulnerable positions. To understand how career agency develops over time and how change becomes possible, we developed a model that visualizes this complex relational process (

Figure 1), based on our theoretical framework and our findings.

Figure 1 shows how young adults and their environments are inextricably related in a dynamic, ongoing process. The (inner) brown circles represent the young adult’s self-perceptions, and the (outer) blue circles reflect how they experience the environments in which they participate. These inner and outer circles are involved in a deeply relational process. A mismatch between how the young adult sees themselves and how they experience the environment may evoke a contradiction, as depicted by the four asterisks in

Figure 1.

On the left side of the model, the significant other is included. This person may play a key role in exploring potential contradictions and possible breakthroughs. This is a process that takes time and is not a quick fix. As the process unfolds, represented at a later stage in the model, a formative intervention from a significant other can result in the young adult imagining new possibilities and forming an intention to act. This moment of inward motion is called an intravention, which sets their development (back) into motion. We refer to this shift as a breakthrough because it involves changing how young adults think, act, and give meaning to their experiences. The model shows this change through color changes: yellow for their transformed self-perceptions and green for their perception of the environment. Importantly, the model is cyclical; each new experience continues to shape and be shaped by the ongoing relationality between the young adult and their environment (

Neuman et al., forthcoming).

Identifying four types of contradictions provides a valuable framework for understanding young adults’ challenges in career development. Our identification of four specific contradictions extends our current understanding of contradictions (

Engeström and Sannino 2011) and conflicts of motives (

Sannino 2015,

2022), offering insights into how young adults encounter and navigate tensions through formative intraventions. This nuanced understanding can strengthen young adults in their development. It benefits young adults and their mentors, as well as others who are significant in their lives, in fostering their career agency by creating interventions tailored to the specific types of contradictions experienced. While the influence of a mentor was outside the scope of this article, the data include numerous examples in which a mentor could facilitate a breakthrough, as was shown by the above-mentioned example of Liam. Our distinction between different types of contradictions contributes to current insights on intraventions (

Sannino et al. 2016) by offering insights into how young adults can act while trying to solve contradictions. In particular, contradictions in which young adults know what they want (contradictions 1 and 2) can be addressed through self-initiated actions (formative intraventions). In these cases, the young adult’s self-initiated actions are still shaped by an interplay with the environment, as their decisions reflect their intrapersonal process of imagined social norms, expectations, and responses to their surroundings. The others are more complex and more difficult for young adults to navigate independently. Contradictions in which young adults are uncertain about their desires (contradictions 3 and 4) are more likely to lead to a paralyzing effect due to internal conflict and unclear direction. These contradictions resemble a critical conflict or double bind (

Engeström and Sannino 2011). As a result, young adults often struggle to resolve these contradictions independently. Mentors can play a crucial role by helping young adults clarify their contradictions and desires and identify actionable steps. However, it may also be true that these contradictions are more challenging for mentors to address effectively. The inherent complexity and deeply personal nature of uncertainty require mentors to employ sensitive and individualized approaches.

Double stimulation (DS) (

Sannino 2015,

2022) was used as a basis for

Figure 1 and can serve as a fundamental concept for mentors. It provides a framework to illustrate a sequence of double stimulation and the emergence of new behaviors that can be integrated into young adults’ lives when they face constraints within a system. However, a broader concept of reconstructing the self may be necessary to understand the various layers within a human being that change as a transformation initiated by DS unfolds. For mentors or significant others, this implies that supporting young adults is about helping them act within a problematic situation and recognizing and facilitating self-redefinition processes. This may require a long-term relationship and a sensitivity to different layers of transformation, which go beyond the problem at hand.

To gain a comprehensive understanding of the transformation of young adults, one can apply the lens of the interplay of personal experiences, emotions, and cultural environments that shape persons and enable persons to construct themselves uniquely (

González Rey 2016). A connection between DS, subjectivity, and career agency (e.g.,

De Hauw and Greenhaus 2015;

De Vos et al. 2020;

Muijen et al. 2018) may be worthwhile. If a chain of DS continues, it may result in young adults adapting to or changing the environments in which they participate. This change could go so far that young adults’ motives, norms, values, needs, self-image, and emotions concerning a particular environment are transformed, causing them to reinvent themselves (

González Rey 2016). Understanding the intricacies of these contradictions will enable the development of more effective mentoring practices, ultimately fostering career agency among young adults.

The limitations of this study lie in the scope of the four contradictions. While they offer a helpful lens for understanding how young adults experience tensions regarding their environments, they may not encompass all possible internal conflicts. Other contradictions may exist, particularly in contexts or populations not represented in this study, such as several female participants who were not part of the current selection. This study included twenty male and five female participants. Although this gender distribution is uneven, no significant differences were noted in how the male and female participants navigated frictions or developed career agency. Nevertheless, it is essential to acknowledge this imbalance, as a more gender-diverse sample in future research could yield deeper insights into potential gendered dimensions of career agency.

In conclusion, while the four types of contradiction offer a promising tool for identifying and, therefore, fostering career agency, the specific challenges associated with contradictions involving unclear desires highlight the need for ongoing research and intervention development. In particular, the challenges evoked by unclear desires need to be addressed. By deepening our understanding of these dynamics, mentors and young adults can be better equipped to navigate the complexities of their changing careers and the changing environments in which they participate.