Children in the CYPSE—Their Views on Their Experiences: A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

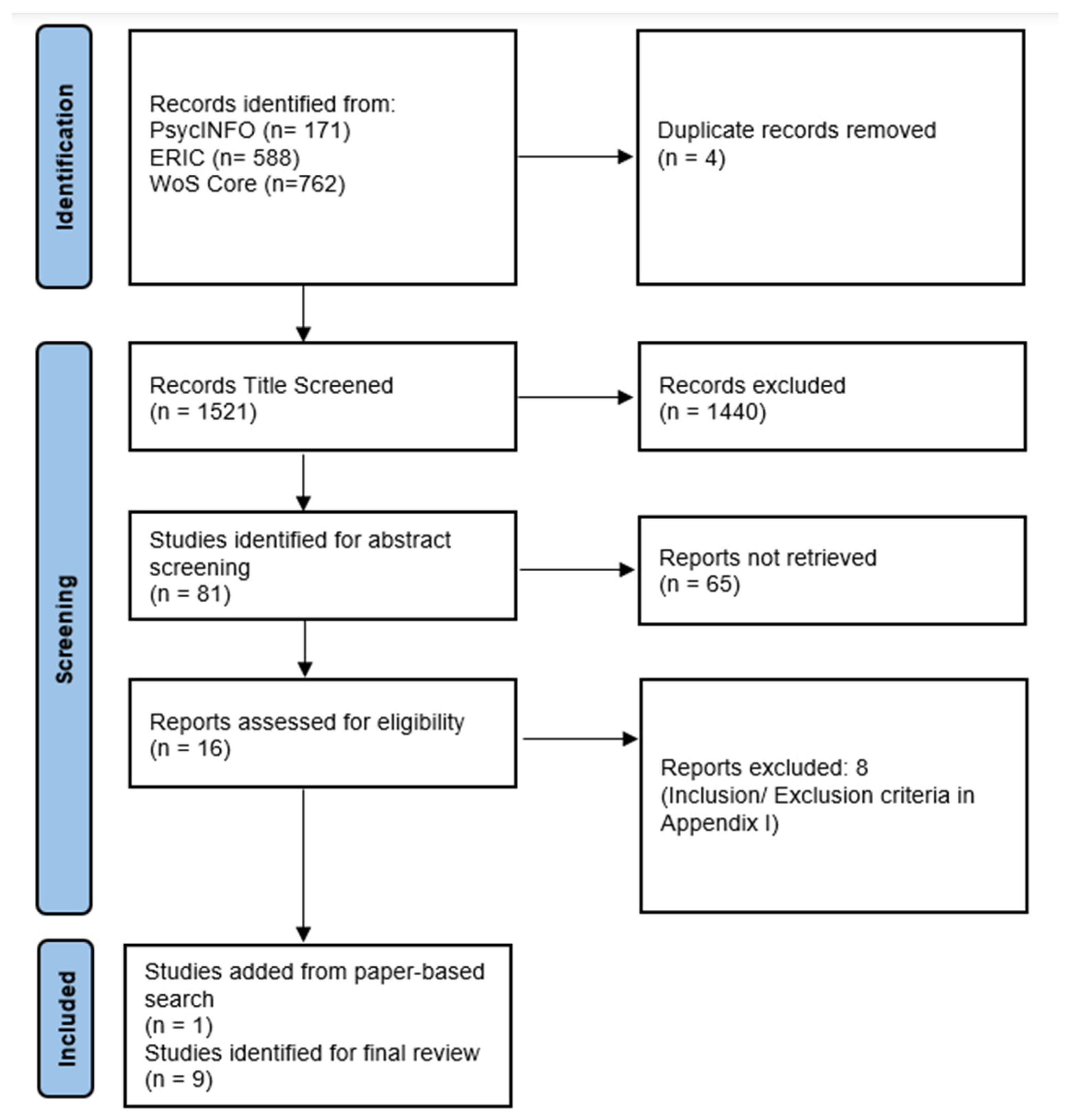

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identification of Studies

2.2. Quality Appraisal

- The quality of reporting (linked to the explicit discussion about sample selection, recruitment alongside aims and context for the study).

- The quality of strategies used to ascertain reliability and validity of measures and methods.

- The quality of how appropriate the methods were for eliciting the voice of the children involved.

3. Methodological Quality

3.1. Source of Views

3.2. Methods

3.3. Context of Participants

- Whether or not the authors stated the reason for participants’ placement within the CYPSE;

- Which of these groups of children were focused upon for their data collection.

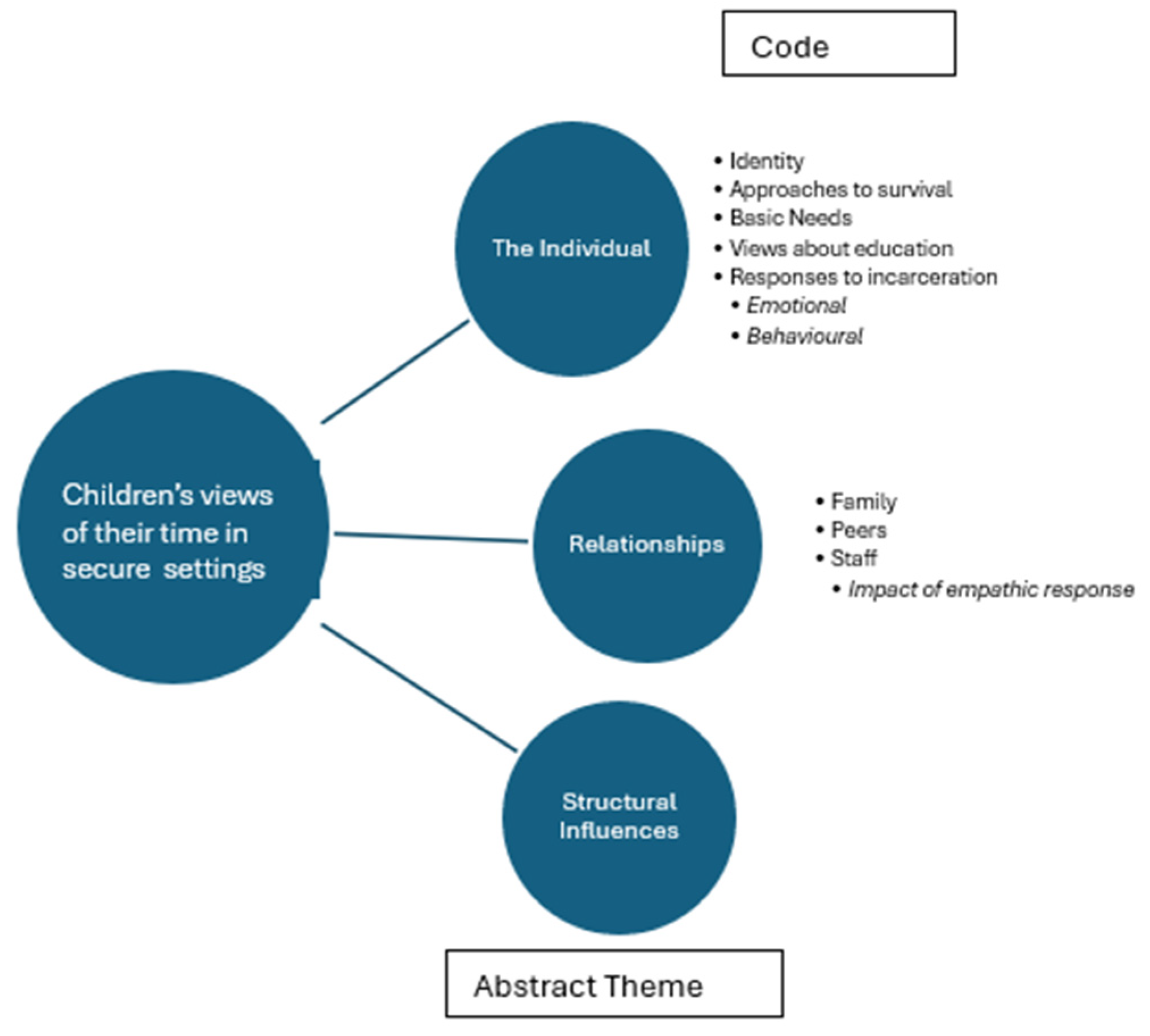

Evaluation and Synthesis

3.4. NB Codes Written in Italics Are Child Codes for the Parent Code

4. Results

4.1. The Individual

4.1.1. Approaches to Survival

4.1.2. Basic Needs

4.1.3. Views on Education

4.1.4. Responses to Incarceration

4.2. Relationships

4.2.1. Family

4.2.2. Peers

4.2.3. Staff

4.3. Structural Influences

5. Discussion

5.1. The Individual

5.2. Unmet Basic Needs and Identity

5.3. Mental Health and Well-Being

5.4. Education as a Protective Factor

5.5. Relationships

5.6. The Role of Staff

5.7. Peer Influence

5.8. Structural Influences

5.9. Past Educational Experiences

Limitations of the Review

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CYPSE | Children and Young People’s Secure Estate |

| ACEs | Adverse Childhood Experiences |

| SEND | Special Educational Needs and Disabilities |

| BAME | Black, Asian, and minority ethnic |

| YJ | Youth Justice |

Appendix A. Weight of Evidence Evaluation

| Article | WoE A Methodological Quality | WoE B Appropriateness of Research Method to Review Question | WoE C Focus of Evidence for Review Question | WoE D Overall Weight of Evidence |

| Shafi (2019) | Medium | Low | Medium (only one type of secure setting) | Medium |

| Brubaker and Cleary (2023) | Medium | Low | Medium | Medium |

| Day (2021) | Low | Low | Medium | Low |

| Ellis (2018) | High | High | Medium (only girls who were on welfare order) | Medium |

| Enell (2017) | Low | High | Low | Medium |

| Jacob et al. (2023) | High | Low | High | Medium |

| Little (2015) | Medium | Low | Medium (only one type of secure setting) | Medium |

| Lyttleton-Smith and Bayfield (2023) | Low | Medium | Low (only one setting and one grp within setting) | Low |

| Reed et al. (2021) | Medium | Medium | Low (only one setting/just girls/US) | Medium |

Appendix B. Themes, Codes, and Illustrative Examples

| Initial Codes | Grandparent | Parent | Child | Illustrative Examples |

| Identity | The Individual | Identity | “When I started using drugs, I didn’t care about anything, only drugs. Before I used drugs, I was still a child, I’m back to that now” (Day 2021, p. 159). | |

| Surviving | Approaches to Survival | “[it was easier to] put up and shut up so you can just get out fast” (Ellis 2018, p. 161) children generally described ‘fighting for who they are’ or ‘relying on themselves’ as the only way to survive being in custody (Day 2021, p. 165). “It is hard to be in a place like this. Even if you might learn something it is a terrible way to do it.” (Enell 2017, p. 134) | ||

| Feelings about food, environment, sleep | Basic needs | One of the main topics of conversation in the discussion groups focusing on education was actually food, hunger and nutrition. (Little 2015, p. 39) Reports included: incorrect clothing sizes provided, dirty clothes or clothes with holes in them…cold or frozen food … expired food…not being allowed to get water to the point of constipation.. hunger and stomach pains…thin clothing and thin blankets… refusals of pads or tampons during their menstrual period…We heard these complaints consistently across several CYA groups. (Lyttleton-Smith and Bayfield 2023, p. 57). | ||

| Frustrations with education | Views about education | “we do crap stuff, like playing board games. I’m fifteen, not twelve!” (Ellis 2018, p. 160). The girls reported that they worked too hard for too few school credits and that instruction was boring. (Reed et al. 2021, p. 59). | ||

| Positives provided by education | “Because if the teacher gives you positive comments: you can do it. It makes you think you can, even if you can’t. It makes you do it.” (Shafi 2019, p. 333) “The subjects I’m doing here will be helpful for me.” (Little 2015, p. 37) | |||

| Education before incarceration | “I kept getting kicked out…I didn’t like people telling me what to do”; “I got kicked out in Year 9” (Little 2015, p. 32). “school prior to incarceration was reported as boring and irrelevant to their lives” (Shafi 2019, p. 333). | |||

| Feelings about the setting and impact on behaviours Worries about the future | Responses to incarceration | Emotional | “I ain’t got nowhere to go when I come out. Accommodation is a big problem for me. I don’t know where I’m gonna live (Little 2015, p. 36). …he had other things to worry about, namely his own personal safety, before concerning himself with his educational development” (Little 2015, p. 36). “they just don’t give a shit. It makes me angry, and I just can’t be bothered with it all” (Shafi 2019, p. 331). | |

| Behavioural | ||||

| Worries about family | Relationships | Role of the family | “You see, my mum used to come and say goodnight and now, when I’m here, when I’ve been away, she has walked [into my room] and said goodnight although no one is there. When I went away she didn’t eat for several days” (Enell 2017, p. 131). | |

| Support from family | “I don’t know how I’d cope to be honest […]. I just appreciate what they’ve done for me innit, and when I get out, I’m going to change” (Day 2021, p. 167). | |||

| Views about their peers | Role of peers | “Peers can work both ways. They can help or they can disrupt” (Shafi 2019, p. 333) They seemed to desire more connection with each other (Reed et al. 2021, p. 59). | ||

| Distrust of staff Frustration with staff | Role of staff | Impact of empathic response | The children discussed the uses of restraint to manage their behaviours, and in particular the unnecessary uses of restraint and excessive force (Day 2021, p. 166). ‘‘I ain’t the one locked up, I can go home the next day, I can go home at this time. You gonna be here, not me.” (Brubaker and Cleary 2023, p. 391) “they say it’s our fault for being here and we deserve to be treated this way; they talk to us and look at us like we are bad people; they command us like dogs” (Reed et al. 2021, p. 58) “officers ask but they do nothing about it. They ask what they could do to help but it’s pointless” (Jacob et al. 2023, p. 6). | |

| Positives about staff | “people can have a laugh with staff, staff tell you like their life, you tell them yours, […] it’s all about the respect” (Jacob et al. 2023, p. 5) “because if the teacher gives you positive comments: you can do it. It makes you think you can, even if you can’t. It makes you do it” (Shafi 2019, p. 33). “They’ll pull you to the side and let you know […] he points this out like “Look. I can’t do this, and this is the reason why…” […] I feel like they still care because they understand how you feel” (Brubaker and Cleary 2023, p. 391). | |||

| Organisation of setting | Structural Influences | The tensions between therapy/rehabilitation and security/punishment, and the impact of those tensions on staff–resident relationships (Brubaker and Cleary 2023, p. 383). Every day you got the same staff, so they give you the opportunity for the staff to really get to know you, get to know how you act… There’s a relationship to be built there, then it can be built better on a community because it’s the same staff (Brubaker and Cleary 2023, p. 387). | ||

| Unfair rules and procedures | …complained about the inaccessible location of secure establishments, the cost of telephone calls to family and friends and that they were often unlocked from their cell to make calls at a time of day when family members and friends may be unavailable (Day 2021, p. 166). Restrictions to learning opportunities associated with their assigned risk level or privilege status. (Little 2015, p. 37). The girls talked often about perceived unfairness in the way that these points were given and taken away and the associated privileges. For example, girls reported that points were sometimes taken away from them without their knowledge, “A” level was extremely difficult to obtain so they lacked motivation to try, some staff were more likely to take away points from certain girls, and rewards were given inconsistently (Reed et al. 2021, p. 58). | |||

| Futility about trying to make changes | Issues with the grievance system came up frequently because when girls would make complaints to JDC staff they were often instructed to ‘file a grievance.’ However, girls indicated that the process of filling out a paper grievance form was rarely effective for receiving a response. (Reed et al. 2021, p. 59) Paul: So, when I was restrained, I had my head down, he just got the keys and on the sly he just flicked it in my eye and hit me in the face. Int: Have you ever complained about things like this? Paul: Yeah, I’ve done it twice in the past, and nothing happens so I can’t be arsed (Day 2021, p. 166). | |||

| Unhelpful timetables and routines | The constraints of the secure custodial setting through its structures of line management had been barriers to engaging in the early stages of the process (Shafi 2019, p. 336). Jeremy abandoned the authentic inquiry when the secure setting was unable to timetable Jeremy to have time with his mentor due to the routines and structure of the secure setting. Upon this, Jeremy showed frustration and aggression and disengaged from the process (Shafi 2019, p. 335). | |||

| Security provided by routine and structures | Most young people described how they settled into a highly structured routine of waking up, meals, education, activities and sleep. Many appeared to have benefited from this with a number saying it made them feel safe (Lyttleton-Smith and Bayfield 2023, p. 10). If someone gets hurt, they can check the cameras, who it was, and what happened and so on. Someone might fall and then they can check, perhaps you say he pushed me and then they can check what really happened (Enell 2017, p. 131). | |||

| Limited choice in education | “I’m doing AS Maths and I can only do that cos there’s someone who can teach me that here” (Little 2015, p. 34). “I can only do what the one-to-one tutor can offer” (Little 2015, p. 37). |

References

- Abram, Karen M., Linda A. Teplin, Gary M. McClelland, and Mina K. Dulcan. 2003. Comorbid psychiatric disorders in youth in juvenile detention. Archives of General Psychiatry 60: 1097–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnert, Elizabeth S., Raymond Perry, Veronica F. Azzi, Rashmi Shetgiri, Gery Ryan, Rebecca Dudovitz, Bonnie Zima, and Paul J. Chung. 2015. Incarcerated youths’ perspectives on protective factors and risk factors for juvenile offending: A qualitative analysis. American Journal of Public Health 105: 1365–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brubaker, Sarah Jane, and Hayley M. D. Cleary. 2023. Connection and caring through a therapeutic juvenile corrections model: Staff and youth resident perceptions of structural and interpersonal dimensions. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology 67: 373–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case, Stephen, Kevin Haines, Sean Creaney, Nicola Coleman, Ross Little, and Victoria Worrall. 2020. Trusting children to enhance youth justice policy: The importance and value of children’s voices. Youth Voice Journal 2020: 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Creaney, Sean. 2014. The benefits of participation for young offenders. Safer Communities 13: 126–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, Anne-Marie. 2021. The experiences of children in custody: A story of survival. Safer Communities 20: 159–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, Katie. 2018. Contested vulnerability: A case study of girls in secure care. Children and Youth Services Review 88: 156–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, Katie, and Penny Curtis. 2021. Care (ful) relationships: Supporting children in secure care. Child & Family Social Work 26: 329–37. [Google Scholar]

- Enell, Sofia. 2017. ‘I Got to Know Myself Better, My Failings and Faults’ Young People’s Understandings of being Assessed in Secure Accommodation. Young 25: 124–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzsimons, Dermot, and Ann Clark. 2021. Pausing mid-sentence: An ecological model approach to language disorder and lived experience of young male offenders. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goffman, Erving. 1961. Asylums. New York: Anchor Books. [Google Scholar]

- Gough, David. 2007. Weight of evidence: A framework for the appraisal of the quality and relevance of evidence. Research Papers in Education 22: 213–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudjonsson, Gisli H., Jon Fridrik Sigurdsson, Inga Dora Sigfusdottir, and Susan Young. 2014. A national epidemiological study of offending and its relationship with ADHD symptoms and associated risk factors. Journal of Attention Disorders 18: 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazel, Neal. 2008. Cross-National Comparison of Youth Justice. London: Youth Justice Board for England and Wales (YJB). [Google Scholar]

- Her Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service, HMPPS. 2021. Youth Justice Statistics. Available online: https://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Children-in-custody-secure-training-centres-and-secure-schools.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2023).

- Hopkins, Thomas, Judy Clegg, and Joy Stackhouse. 2016. Young offenders’ perspectives on their literacy and communication skills. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders 51: 95–109. [Google Scholar]

- Howard League for Penal Reform. 2022. Children on Remand: Voices and Lessons. England and Wales. Available online: https://howardleague.org/publications/children-on-remand/ (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- Hughes, Nathan. 2015. Understanding the influence of neurodevelopmental disorders on offending: Utilizing developmental psychopathology in biosocial criminology. Criminal Justice Studies: A Critical Journal of Crime, Law and Society 28: 39–60. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, Nathan, Huw Williams, Prathiba Chitsabesan, Rebecca Davies, and Luke Mounce. 2012. Nobody Made the Connection: The Prevalence of Neurodisability in Young People Who Offend; London: Office of the Children’s Commissioner for England.

- Jacob, Jenna, Sophie D’Souza, Rebecca Lane, Liz Cracknell, Rosie Singleton, and Julian Edbrooke-Childs. 2023. “I’m not Just Some Criminal, I’m Actually a Person to Them Now”: The Importance of Child-Staff Therapeutic Relationships in the Children and Young People Secure Estate. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health 23: 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juliana, Jesika, Fonny Dameaty Hutagalung, and Azmawaty Mohamad Nor. 2024. Psychological Experience of Juvenile Offenders in Correctional Institutions: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies. Journal of Population and Social Studies [JPSS] 32: 609–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambie, Ian, and Isabel Randell. 2013. The impact of incarceration on juvenile offenders. Clinical Psychology Review 33: 448–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, Jodi, Lonn Lanza-Kaduce, Charles E. Frazier, and Donna M. Bishop. 2002. Adult versus juvenile sanctions: Voices of incarcerated youths. Crime & Delinquency 48: 431–55. [Google Scholar]

- Little, Ross. 2015. Putting education at the heart of custody? The views of children on education in a Young Offender Institution. British Journal of Community Justice 13: 27. [Google Scholar]

- Lyttleton-Smith, Jen, and Hannah Bayfield. 2023. Dragged kicking and screaming: Agency and violence for children entering secure accommodation. Children & Society 38: 317–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mays, Nicholas, and Catherine Pope. 2000. Qualitative research in health care. Assessing quality in qualitative research. British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Education) 320: 50–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, Linda Weaver, and Margaret Miller. 1999. Initiating research with doubly vulnerable populations. Journal of Advanced Nursing 30: 1034–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Audit Office. 2022. Children in Custody: Secure Training Centres and Secure Schools; London: National Audit Office. Available online: https://www.nao.org.uk/reports/children-in-custody/ (accessed on 14 July 2023).

- Nolet, Anne-Marie, Yanick Charette, and Fanny Mignon. 2022. The effect of prosocial and antisocial relationships structure on offenders’ optimism towards desistance. Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal Justice 64: 59–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noyes, Jane, Andrew Booth, Kate Flemming, Ruth Garside, Angela Harden, Simon Lewin, Tomas Pantoja, Karin Hannes, Margaret Cargo, and James Thomas. 2018. Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group Guidance Paper 3: Methods for assessing methodological limitations, data extraction and synthesis, and confidence in synthesized qualitative findings. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 97: 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Grady, Emmanuel. 2017. ‘Learning to be more human’: Perspectives of respect by young Irish people in prison. Journal of Prison Education and Re-Entry 4: 4–16. [Google Scholar]

- Oostermeijer, Sanne, Poni Tongun, and Diana Johns. 2024. Relational security: Balancing care and control in a youth justice detention setting in Australia. Children and Youth Services Review 156: 107312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pederson, Casey A., Paula J. Fite, and Jonathan L. Poquiz. 2021. Demographic differences in youth perceptions of staff: A national evaluation of adjudicated youth. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology 65: 1143–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyle, Nicole, Andrea Flower, Anna Mari Fall, and Jacob Williams. 2016. Individual-level risk factors of incarcerated youth. Remedial and Special Education 37: 172–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, Lauren A., Jill D. Sharkey, and Althea Wroblewski. 2021. Elevating the voices of girls in custody for improved treatment and systemic change in the juvenile justice system. American Journal of Community Psychology 67: 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, Lynne, Jane Hurry, Margaret Simonot, and Anita Wilson. 2014. The Aspirations and Realities of Prison Education for Under-25s in the London Area. London: London Review of Education. [Google Scholar]

- Sander, Janay B., Jill D. Sharkey, Roger Olivarri, Diane A. Tanigawa, and Tory Mauseth. 2010. A qualitative study of juvenile offenders, student engagement, and interpersonal relationships: Implications for research directions and preventionist approaches. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation 20: 288–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafi, Adeela. 2019. The complexity of disengagement with education and learning: A case study of young offenders in a secure custodial setting in England. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk (JESPAR) 24: 323–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, Jennifer L., Robert Bozick, and Lois M. Davis. 2016. Education for incarcerated juveniles: A meta-analysis. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk (JESPAR) 21: 65–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Charlie. 2016. Review of the Youth Justice System in England and Wales; London: Ministry of Justice.

- Thomas, James, and Angela Harden. 2008. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology 8: 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. 1989. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC). General Assembly Resolution 44/25, 20 November 1989. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/child-rights-convention/convention-text (accessed on 14 July 2023).

- Welland, Sarah, Linda J. Duffy, and Bahman Baluch. 2020. Rugby as a rehabilitation program in a United Kingdom Male Young Offenders’ Institution: Key findings and implications from mixed methods research. Journal of Exercise Rehabilitation 16: 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youth Custody Service. 2023. Youth Custody Data 14 July 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/youth-custody-data (accessed on 14 July 2023).

| Type of Setting | Description |

|---|---|

| Secure Children Homes | Accommodating the most vulnerable children in small settings with high staff-to-child ratios including children who are typically 10–17 years old. |

| Young Offender Institutions | Larger settings which have a closer resemblance to traditional adult prisons and typically include children who are 15–17 years old. |

| Secure Training Centres | Larger than SCHs but smaller than YOIs and accommodate children who are too vulnerable for a YOI. Typical ages within these centres are in the range of 12–17 years |

| Secure School | For children aged 12–18 years on remand or sentenced to custody. |

| Key Concept | Search Terms | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Secure Accommodation | “Secure accommod*” OR “Child* prison*” OR “You* Offend* Institution*” OR “Secure Child* home*” OR “Juvenile* Detention*” |

| 2 | Incarcerated CYP | “Incarcerate* Child*” OR “Incarcerate* you*” OR “Incarcerate* you* people” OR “Child* in prison” OR “Young Offender*” OR “Juvenile Offender” |

| 3 | Views of CYP | View* OR Perspective OR Opinion* |

| Areas of Focus | Inclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Topic of study | Child views on their time within a secure setting. Their views about the setting that they have been placed in Children aged 10–18-years old at time of incarceration |

| Study methodology | Qualitative study exploring views of CYP |

| Evidence base | Peer-reviewed journal articles: empirical studies; conceptual papers based on a clear methodology; meta-analyses fields of social sciences, psychology, and education |

| Other criteria | written in English, publication date from 2000. |

| Research Study: Author and Year | Participants | Nature of Views Sought | Data Collection Methods | Key Findings | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age of CYP | Country and Nature of Secure Setting | Current or Retrospective Views | ||||

| Shafi (2019) | 13–17 years | England, Secure Children’s Home | Current accounts | Views of children in secure settings about their education, factors around educational engagement and journey to incarceration. | Semi-structured interviews and observations (Phase I), case study (Phase II) | Identified opportunities and barriers for re-engagement with learning based on psychological needs in relation to feelings of competency, supportive relationships, and autonomy. |

| Brubaker and Cleary (2023) | 15–20 years | US, Juvenile Detention Centre | Current accounts | Views of children on the quality of their relationships and impact of structural changes in their secure setting. | Phase I focus groups (staff and YP), Phase II quantitative analysis of themes generated in Phase I | YP found having consistency in staff as helpful. YP found change to discussing issues with them rather than staff ‘writing them up’ as being helpful. |

| Day (2021) | 15–18 years | England, Secure Children’s Home, Secure Training Centre, Young Offender Institution | Included boys who had left the setting within the past year. | The views of children who have been placed in YOIs about their time within the institution. | Semi-structured interviews | Views of the children about their behaviour management and how this was used to control and keep them in their ‘place’. Too much time spent alone and isolated. Limited opportunities to maintain contact with outside world. Made specific recommendations for future practice in YOI’s. |

| Ellis (2018) | 13–16 years | England, Secure Children’s Home | Current accounts | Female children’s perspectives about their pathway into secure care and their views about life within the institution. | Participant observation, semi-structured interviews, case note analysis | Dissonance between staff and child perceptions as to their vulnerability (majority of girls denied their vulnerability). Girls had missed out on childhood. Challenges over placement of two groups of girls; those who were placed for welfare reasons and those who were placed as a result of engaging in criminal behaviour. |

| Enell (2017) | 12–18 years | Sweden, Secure Unit | Current and retrospective accounts from same participants | Primary focus around children’s views of assessments conducted whilst they were securely accommodated but also considers their views of the secure accommodation. | Semi-structured interviews | A number of children did not know why they had been placed. Their experiences of the assessment were dependent on the situation and interpersonal interactions during the assessment process rather than the assessment itself. Implications for practice around place and context of assessment were made. |

| Jacob et al. (2023) | 16–18 years | England, Young Offender Institution, Secure Children’s Home, Secure Training Centre | Current accounts | Children’s views on a specific programme focusing upon relationships and the impact of this programme of their time within secure settings. | Semi-structured interviews, focus group | Importance of positive relationships between staff and children. Need for children to be treated with respect. Differences in relationships identified and perceived by the children across the different secure estate settings; more positive in Secure Children’s Homes and Secure Training Centres than Young Offender Institutions. |

| Little (2015) | 15–17-year olds | England, Young Offender Institution | Current accounts | Children’s views on their experiences within a Young Offender Institution and an evaluation of what works/does not work. | Questionnaire, discussion groups, semi-structured interviews | Identification of poor educational experiences leading up to incarceration. Children in secure settings need to be able to make choices about their education but there are practical barriers which also have a negative influence on engagement. Emphasises importance of listening to children about the educational experiences to then impact on provision. |

| Lyttleton-Smith and Bayfield (2023) | Wales, England, and Scotland Secure Children’s Home | Current and retrospective | Views of children about their time in the secure setting specifically exploring agency through their narratives. | Semi-structured interviews, documentary analysis of case files | The suppression of agency in children through incarceration leads to violence. | |

| Reed et al. (2021) | Under 18’s | US Juvenile Detention Centre | Current | Views of female children about their experiences within a juvenile detention centre. | Semi-structured interviews | As a result of an advisory group created by the research team the girls feedback led to improved services and treatment. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Templeton, S.; Hayes, B. Children in the CYPSE—Their Views on Their Experiences: A Systematic Literature Review. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 318. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14050318

Templeton S, Hayes B. Children in the CYPSE—Their Views on Their Experiences: A Systematic Literature Review. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(5):318. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14050318

Chicago/Turabian StyleTempleton, Sian, and Ben Hayes. 2025. "Children in the CYPSE—Their Views on Their Experiences: A Systematic Literature Review" Social Sciences 14, no. 5: 318. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14050318

APA StyleTempleton, S., & Hayes, B. (2025). Children in the CYPSE—Their Views on Their Experiences: A Systematic Literature Review. Social Sciences, 14(5), 318. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14050318