Feasibility of Tiyanjane: A Family–School–Community Intervention Promoting Parental Involvement in the Education of Children with Disabilities in Malawi

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Setting

2.3. The Intervention

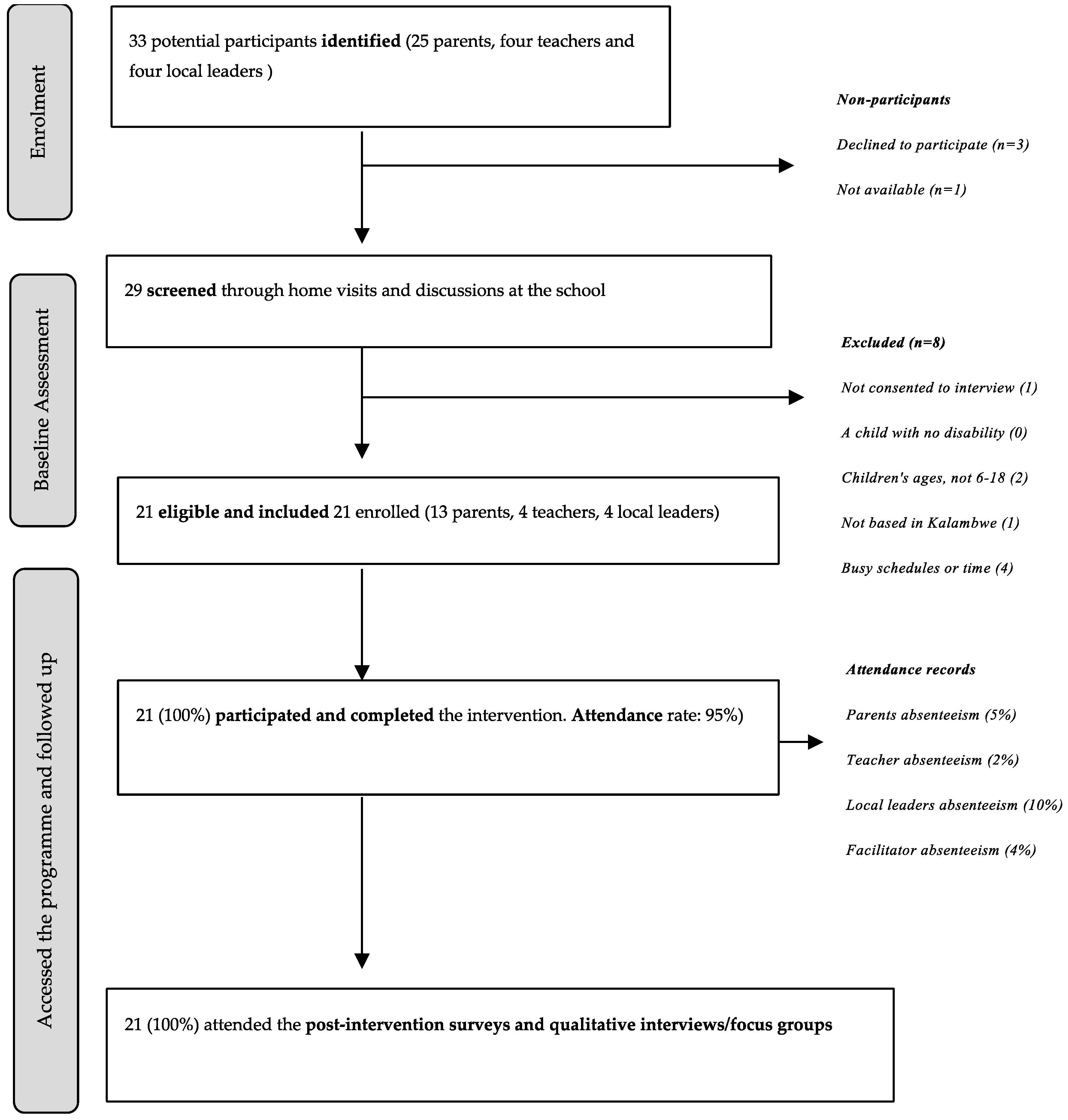

2.4. Participants and Recruitment

2.5. Data Collection

2.5.1. Quantitative Measures

2.5.2. Observational Monitoring

2.5.3. Qualitative Measures

2.6. Data Management and Analysis

2.7. Researcher Reflexivity, Positionality, and Trustworthiness

3. Results

3.1. Acceptability

3.1.1. Perceived Appropriateness

3.1.2. Initial Resistance

3.1.3. Satisfaction

3.1.4. Intent to Continue the Use

3.2. Demand

3.2.1. Actual Use

3.2.2. Expressed Demand

3.2.3. Perceived Benefits

3.3. Implementation

3.3.1. Degree of Execution

3.3.2. Success or Failure of Execution

3.4. Practicality

3.4.1. Factors Affecting Implementation

3.4.2. Amount or Types of Resources Needed to Implement

3.5. Limited Efficacy

3.5.1. Effects on Parents’ Behaviours

3.5.2. Effects on Perceived Social Support

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Construct | Areas of Focus/Analysis Code | Meaning of Analysis Code | Sources of Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acceptability To what extent was the programme suitable, satisfying, or attractive to programme recipients? | Perceived Appropriateness | How well participants believe Tiyanjane fits within the cultural, educational, or social framework of their community. This includes views on whether program activities, focus, and methods align with their values and needs. | FGDs and IDIs Recruitment and retention flow of participants |

| Initial Resistance | This reflects participants’ initial reluctance, doubts, or fear of joining the program or their hesitation towards certain activities. It includes cultural resistance, lack of understanding, or mistrust of the program’s goals. | ||

| Satisfaction or Dissatisfaction with Participation | Refers to the level of satisfaction or dissatisfaction expressed by participants (parents, facilitators, and teachers) with Tiyanjane. It captures how they feel about their involvement, the program activities, and results observed in their children or within the community. | ||

| Intent to Continue | Captures participants’ desire or intention to continue applying the methods or lessons from Tiyanjane after the formal program ends. It also includes challenges related to continued use of Tiyanjane. | ||

| Demand To what extent was the programme used, and/or is it likely to be used? | Actual Use | Participants’ initial reluctance, doubts, or fear of joining the program or their hesitation towards certain activities. It includes cultural resistance, lack of understanding, or mistrust of the program’s goals. | FGDs and IDIs Sociodemographic data Monitoring data: Fidelity checklist and attendance register After action reviews |

| Expressed Demand | Focuses on the level of interest or intention expressed by participants to engage in, continue, or discontinue with Tiyanjane or similar interventions. | ||

| Perceived Benefits | Refers to the perceived need for Tiyanjane or similar interventions within the community. This code also includes any mention of growing interest from families or communities that were not initially part of the program. | ||

| Implementation To what extent and in what manner is the intervention successfully delivered to the intended participants? | Degree of Execution | Refers to how well the planned activities of Tiyanjane were carried out according to schedule and expectations. | FGDs and IDIs Sociodemographic data Monitoring data After action reviews |

| Success or Failure of Execution | Focuses on the overall success or failure of specific activities or components of the program. It considers whether activities met their objectives and the reasons behind their success or failure. | ||

| Amount or Types of Resources Needed to Implement | Captures the resources (e.g., time, materials, financial support) required to successfully implement the Tiyanjane program, as well as any gaps in these resources that affected implementation. | ||

| Practicality To what extent has the intervention been delivered to the intended participants using available means, resources, and circumstances? | Factors Affecting Implementation | Reported issues or factors that either facilitate or hinder the smooth implementation of Tiyanjane. Coders should identify references to logistical, cultural, financial, or resource-related challenges that made implementing the program difficult, as well as aspects that made it easier (e.g., community support, alignment with cultural values, or availability of resources). Factors can include parental willingness, teacher cooperation, community infrastructure, or external support. | FGDs and IDIs Monitoring data: Fidelity checklist and attendance register |

| Success or Failure of Execution | The degree to which participants and facilitators were able to carry out the activities as intended by Tiyanjane. Deviations or challenges that prevented participants from adhering to the program’s intended structure are also noted. | ||

| Limited Efficacy To what extent does the intervention show promise of being effective and successful with the intended population | Impact on Parents’ Behaviour | Direct or indirect positive or negative changes made or experienced by Tiyanjane participants, particularly on parental practices, e.g., consistency, coerciveness, and encouragement as well as family adjustment, including family relationships and parental teamwork. | Pre- and post-surveys FGDs |

| Family Functioning Support and Relationships | Refers to perceived outcomes of Tiyanjane, especially in terms of improvements in reported support by the participants from family, friends and significant others. |

| Item | Description |

|---|---|

| Name | Tiyanjane: A family–school–community intervention promoting parental involvement in the education of children with disabilities in Malawi. |

| Why | To promote family–school–community collaboration and foster a supportive network by enhancing parental knowledge, opportunities, and confidence in advocating for inclusive practices and ultimately improving the educational experiences of children with disabilities. |

| Who (Participants) | Participants included caregivers of children with disabilities, teachers, and community leaders from the Kalambwe School catchment area. Caregivers were eligible if they were 18 years or older, caring for a school-aged child (6–17 years) with a disability enrolled at Kalambwe Primary School, resided locally, and could commit to the 12-week programme. Caregivers were identified in collaboration with local gatekeepers, including school authorities and representatives from the CCAP Inclusive Education Programme and MACOHA. Eligible caregivers were purposively selected to ensure a mix of impairment types and demographic diversity, although in practice, most children had physical, hearing, or visual impairments, with no caregivers of children with intellectual disabilities available. Teachers were eligible if they were currently teaching at Kalambwe Primary School and had one or more learners with disabilities in their classroom. Community leaders were selected based on their involvement in school governance or community-based support structures (e.g., School Management Committees, PTAs, or Mother Groups). They were eligible if they resided in the Kalambwe area and held a leadership or support role relevant to school or disability inclusion. All the participants were eligible if they were willing to participate in the programme for its full duration and consented to be part of the study. |

| What (Materials) | Participants received training handouts, worksheets containing the necessary materials, and activity instructions for each session. Promotional materials like branded homework booklets, bags, and T-shirts were provided to enhance visibility and community engagement. Visual aids/flipcharts, games, songs, and storytelling techniques were used during training sessions. |

| What (Procedures) | The intervention involved 10 weekly participatory sessions split into two phases. Each phase was preceded by three days of training the participants (parents, teachers, and local leaders ), followed by weekly practical sessions over five weeks to reinforce and practice the skills learned. The study participants represented three groups that met specific criteria: caregivers, teachers, and local leaders. Caregivers were adults aged 18 and older responsible for children with disabilities between the ages of 6 and 17 enrolled at Kalambwe Primary School. Teachers taught at least two students with disabilities in their classes, while local leaders were active members of the school’s management committee. |

| Who Provided | The Principal Investigator provided four facilitators (two females and two males) with an initial five-day training, which they then delivered to 21 participants: four local leaders, four teachers, and 13 parents. |

| How | Sessions were conducted with parents, teachers, and local leaders in large and small groups. All the activities were delivered face-to-face in school, community, and home settings, encouraging participatory learning and engagement. |

| Where | Sessions took place at a local rural primary school and within participants’ residences for home visits for personalised family support and activity planning. |

| When and How Much | The intervention lasted 12 weeks, with one 2-hour session per week. All the activities were conducted during term time, and no activities were conducted during school holidays. Necessary infrastructure included meeting spaces at the school, and we reimbursed all the participants and facilitators for weekly transport expenses. |

| Tailoring | The intervention was tailored to Malawi’s local educational and sociocultural context. Small groups, known as T-hubs, allowed the facilitators to personalise their support based on the participants’ specific needs. |

| Modifications | Slight modifications were made based on feedback from participants during weekly after-action reviews. For example, to address initial concerns, additional focus was placed on supporting parents’ understanding of disabilities during home visits. The days for community awareness and family time activities were moved to more suitable days. |

| How Well (Planned) | Fidelity was monitored through facilitator reports, after-action reviews, and attendance registers. The principal investigator and a local project support group supported facilitators weekly and continuously to ensure the intervention was delivered consistently according to the protocol. |

| How Well (Actual) | The intervention was delivered as planned, with high levels of engagement from both participants and facilitators. Some families who were initially hesitant became more engaged as the programme progressed. |

| Session | Topic | Activity Description for Each Session |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Creating a Support System | Home visits by teachers and community leaders to understand family needs and priorities. |

| 2 | Goal Setting and Action Plans | Caregivers, teachers, and leaders develop individualised education support plans for children and families. |

| 3 | Supporting Children to Learn at Home | Strategies for assisting children with homework and academic engagement. |

| 4 | Volunteering in Schools | Caregivers, teachers, and leaders participate in schoolwork activities to enhance engagement. |

| 5 | Strengthening Family Bonds | Fun family days and activities to support emotional well-being. |

| 6 | Parent–Teacher–Child Conferences | Structured feedback meetings to track student progress and to set learning goals. |

| 7 | Classroom Observations | Parents and community leaders observe and provide feedback on inclusive teaching practices. |

| 8 | Advocacy and Influence | Training of participants on disability rights and advocacy for inclusive education policies. |

| 9 | Action Plan Follow-Ups | Review of previous commitments and progress in supporting children’s education. |

| 10 | Community Awareness Event | Parents, teachers, and leaders campaign on the importance of disability-inclusive education. |

References

- Alflasi, Maryam, Fatima Al-Maadadi, and Chris Coughlin. 2018. Perspectives of family-school relationships in Qatar based on Epstein’s model of six types of parent involvement. An International Research Journal 40: 188–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, Lena Morgon, Hannah Kuper, and Sarah Polack. 2017. Poverty and disability in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 12: e0189996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, Lena M., Xanthe Hunt, Khumbo Kalua, Providence Nindi, Maria Zuurmond, and Tom Shakespeare. 2022. ‘I might be lucky and go back to school’: Factors affecting inclusion in education for children with disabilities in rural Malawi. African Journal of Disability 11: 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, Lena Morgon, and Maria Zuurmond. 2015. Barriers and Enablers to Inclusion in Education for Children with Disabilities in Malawi. London: The London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, pp. 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Bariroh, Siti. 2018. The Influence of Parents’ Involvement on Children with Special Needs’ Motivation and Learning Achievement. International Education Studies 11: 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, Ana A., Melanie M. Domenech Rodríguez, Elizabeth Wieling, J. Rubén Parra-Cardona, Laura A. Rains, and Marion S. Forgatch. 2019. Teaching GenerationPMTO, an evidence-based parent intervention, in a university setting using a blended learning strategy. Pilot Feasibility Studies 5: 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergold, Jarg, and Stefan Thomas. 2012. Participatory Research Methods: A Methodological Approach in Motion. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research 13: 191–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, Deborah J., Matthew Kreuter, Bonnie Spring, Ludmila Cofta-Woerpel, Laura Linnan, Diane Weiner, Suzanne Bakken, Cecilia Patrick Kaplan, Linda Squiers, Cecilia Fabrizio, and et al. 2009. How We Design Feasibility Studies. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 36: 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, Nadia, Zara Quigg, Rebecca Bates, Lisa Jones, Emma Ashworth, Steve Gowland, and Margaret Jones. 2022. The Contributing Role of Family, School, and Peer Supportive Relationships in Protecting the Mental Wellbeing of Children and Adolescents. School Mental Health 14: 776–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Michelle, Ray Fitzpatrick, Andrew Haines, Ann Louise Kinmonth, Peter Sandercock, David Spiegelhalter, and Peter Tyrer. 2000. Framework for design and evaluation of complex interventions to improve health. BMJ 321: 694–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, Peter, Paul Dieppe, Sally Macintyre, Susan Michie, Irwin Nazareth, and Mark Petticrew. 2008. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: The new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 337: 979–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowe, John, Joseph A. Allen, Cliff W. Scott, Mackenzie Harms, and Michael Yoerger. 2017. After-action reviews: The good behavior, the bad behavior, and why we should care. Safety Science 96: 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, Beáta Andrea, Tímea Szűcs, Regina Sávai-Átyin, Anett Hrabéczy, Karolina Eszter Kovács, Gabriella Ridzig, Dávid Kis, Katinka Bacskai, and Gabriella Pusztai. 2024. Narrowing the inclusion gap–teachers and parents around SEN students. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 1–27, Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degnan, Amy, Sophie Baker, Dawn Edge, Will Nottidge, Melissa Noke, Claire Jude Press, Nusrat Husain, Shanaya Rathod, and Richard James Drake. 2018. The nature and efficacy of culturally-adapted psychosocial interventions for schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine 48: 714–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldridge, Sandra M., Claire L. Chan, Michael J. Campbell, Christine M. Bond, Sally Hopewell, Lehana Thabane, and Gillian A. Lancaster. 2016. CONSORT 2010 statement: Extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. Pilot Feasibility Studies 2: 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, Joyce L. 2018. School, family and community partnerships: Preparing educators and improving schools. In School, Family, and Community Partnerships: Preparing Educators and Improving Schools, 2nd ed. New York: Routledge, pp. 1–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, Nicola K., Gemma Heath, Elaine Cameron, Sabina Rashid, and Sabi Redwood. 2013. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Medical Research Methodology 13: 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbacz, S. Andrew, Philippa S. McDowall, Elizabeth Schaughency, Susan M. Sheridan, and Greg W. Welch. 2015. A Multidimensional Examination of Parent Involvement across Child and Parent Characteristics. The Elementary School Journal 115: 384–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthold, Regina, Laura Kann, Lubna Bhatti, Parviz Abduvahobov, Joana Ansong, Uki Atkinson, Valentina Baltag, Sonja Caffe, Roberta Caixeta, Cheick Bady Diallo, and et al. 2023. Effectiveness of a participatory approach to develop school health interventions in four low resource cities: Study protocol of the ‘empowering adolescents to lead change using health data’ cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 13: e071353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldane, Victoria, Fiona L. H. Chuah, Aastha Srivastava, Shweta R. Singh, Gerald C. H. Koh, Chia Kee Seng, and Helena Legido-Quigley. 2019. Community participation in health services development, implementation, and evaluation: A systematic review of empowerment, health, community, and process outcomes. PLoS ONE 14: e0216112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallingberg, Britt, Ruth Turley, Jeremy Segrott, Daniel Wight, Peter Craig, Laurence Moore, Simon Murphy, Michael Robling, Sharon Anne Simpson, Graham Moore, and et al. 2018. Exploratory studies to decide whether and how to proceed with full-scale evaluations of public health interventions: A systematic review of guidance. Pilot and Feasibility Studies 4: 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, Alison B., and Erin P. Finley. 2019. Qualitative Methods in Implementation Research: An Introduction. Psychiatry Research 280: 112516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, Tammy C., Paul P. Glasziou, Isabelle Boutron, Ruairidh Milne, Rafael Perera, David Moher, Douglas G. Altman, Virginia Barbour, Helen MacDonald, Marie Johnston, and et al. 2016. Better Reporting of Interventions: Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) Checklist and Guide. Gesundheitswesen 78: 175–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, Yeon-Jae, Yeon-Jae Jeong, and Jeong-A. Bang. 2013. Effect of social support on parenting stress of korean mothers of children with cerebral palsy. Journal of Physical Therapy Science 25: 1339–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Joy Caño, Kathlene, Mary Grace Cape, Jacient Mar Cardosa, Carolyn Miot, Gee Rianne Pitogo, Cherrie Mae Quinio, and Jewish Merin. 2016. Parental Involvement on Pupils’ Performance: Epstein’s Framework. The Online Journal of New Horizons in Education 6: 143–50. [Google Scholar]

- Jumbe, Sandra, Joel Nyali, Maryrose Simbeye, Nelson Zakeyu, Gase Motshewa, and Subba Rao Pulapa. 2022. ‘We do not talk about it’: Engaging youth in Malawi to inform adaptation of a mental health literacy intervention. PLoS ONE 17: e0265530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, Eliza, Jamin J. Day, Julie Hodges, Cassandra L. Tellegen, Tianyi Ma, Matthew R. Sanders, Bruce Tonge, Stewart Einfeld, Kate Sofronoff, Kylie M. Gray, and et al. 2022. Parental Adjustment Scale: Validation of a brief, five-item measure of parental adjustment for use with families of typically developing children and children with developmental and/or intellectual disabilities in Australia. Research in Developmental Disabilities 128: 104304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimaro, Anathe R., and Haruni J. Machumu. 2015. Impacts of parental involvement in school activities on academic achievement of primary school children. International Journal of Education and Research 3: 483–94. [Google Scholar]

- Klein-Cox, Amanda, Angela Tobin, and Ramona Denby. 2023. When Kinship Caregivers Became Teachers: Role Stress and Strain from Remote Learning during COVID-19. Societies 13: 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuper, Hannah, Ashrita Saran, Howard White, Jill Adona, Nina Ashley De La Cruz, Yashik Kanojia, Suresh Kumar, Shaileja Tetali, Lovely Tolin, Thirumugam Muthuvel, and et al. 2018. Rapid Evidence Assessment (REA) of What Works to Improve Educational Outcomes for People with Disabilities in Low-and Middle-Income Countries. Oslo and London: Campbell Collaboration and International Centre for Evidence in Disability. [Google Scholar]

- Kuper, Hannah, Andrew Sentoogo Ssemata, Tracey Smythe, Joanna Drazdzewska, Peter Waiswa, Patrick Kagurusi, Mikey Rosato, and Femke Bannink Mbazzi. 2023. Is it feasible to implement a community-based participatory group programme to address issues of access to healthcare for people with disabilities in Luuka district Uganda? A study protocol for a mixed-methods pilot study. BMJ Open 13: e074217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Jeongmin. 2022. “I always tell my children to learn from me”: Parental engagement in social and emotional learning in Malawi. International Journal of Educational Research 116: 102090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linden, Mark A., Rachel Leonard, Trisha Forbes, Michael Brown, Lynne Marsh, Stuart Todd, Nathan Hughes, and Maria Truesdale. 2024. Randomised controlled feasibility study protocol of the Carers-ID online intervention to support the mental health of family carers of people with intellectual disabilities. Pilot and Feasibility Studies 10: 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ljungberg, Malin, and Ulla-Karin Schön. 2023. Who cares? A scoping review about the experiences of parental caregivers of autistic adults. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 36: 929–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, Paul, Helen M. Nabwera, Harriet M. Babikako, Muneera Rasheed, Kirsten A. Donald, Emmie W. Mbale, Elizabeth Stockdale, Prem Chand, Meta Van Den Heuvel, Angelina Kakooza Mwesige, and et al. 2024. Experiences of identifying pre-school children with disabilities in resource limited settings—An account from Malawi, Pakistan and Uganda. Disability and Society 39: 2053–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, Rafaela Costa, Hugo S. Gomes, Andreas Bauer, Maurício Scopel Hoffmann, de Christian Loret Mola, Elisa Rachel Pisani Altafim, Marlos Rodrigues Domingues, and Joseph Murray. 2024. The Parenting and Family Adjustment Scales (PAFAS) questionnaire: Psychometric Qualities of the Parenting Scale in Two Large Brazilian Birth Cohorts. MedRxiv: The Preprint Server for Health Sciences. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbazzi, Femke Bannink, Ruth Nalugya, Elizabeth Kawesa, Harriet Nambejja, Pamela Nizeyimana, Patrick Ojok, Geert Van Hove, and Janet Seeley. 2020. ‘Obuntu Bulamu’—Development and Testing of an Indigenous Intervention for Disability Inclusion in Uganda. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research 22: 403–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLinden, Mike, Paul Lynch, Anita Soni, Alfredo Artiles, Foster Kholowa, Elizabeth Kamchedzera, Jenipher Mbukwa, and Mika Mankhwazi. 2018. Supporting Children with Disabilities in Low- and Middle- Income Countries: Promoting Inclusive Practice within Community-Based Childcare Centres in Malawi through a Bioecological Systems Perspective. International Journal of Early Childhood = Revue Internationale de l’enfance Prescolaire = Revista Internacional de La Infancia Pre-Escolar 50: 159–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejia, Anilena, Ania Filus, Rachel Calam, Alina Morawska, and Matthew R. Sanders. 2014. Measuring Parenting Practices and Family Functioning with Brief and Simple Instruments: Validation of the Spanish Version of the PAFAS. Child Psychiatry and Human Development 46: 426–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Moreau, David, and Kristina Wiebels. 2021. Assessing Change in Intervention Research: The Benefits of Composite Outcomes. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musendo, David John, Blessings Chirwa, Chisomo Kamata, Daksha Patel, Tracey Smythe, and Sarah Polack. 2025. Co-Designing Tiyanjane, a Participatory Intervention to Promote Parental Involvement in the Education of Children with Disabilities in Malawi. Disabilities 5: 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musendo, David John, Maria Zuurmond, Thomas Andrea Nkhonjera, Sarah Polack, and Daksha Patel. 2024. “It Is My Responsibility to Escort My Child to School …” Factors Influencing Parental Involvement in Educating Children with Disabilities in Malawi. Social Sciences 13: 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musendo, David John, Nathaniel Scherer, Joyline Jepkosgei, Lillian Maweu, Audrey Mupiwa, Onai Hara, Sarah Polack, and Daksha Patel. 2023. A Systematic Review of Interventions Promoting Parental Involvement in the Education of School-Aged Children With Disabilities. Australasian Journal of Special and Inclusive Education 47: 123–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalugya, Ruth, Harriet Nambejja, Claire Nimusiima, Elizabeth S. Kawesa, Geert van Hove, Janet Seeley, and Femke Bannink Mbazzi. 2023. Obuntu bulamu: Parental peer-to-peer support for inclusion of children with disabilities in Central Uganda. African Journal of Disability 12: 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Statistics Office. 2019. 2018 Malawi Population. Available online: https://www.nsomalawi.mw/census/2018 (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- O’Cathain, Alicia, Pat Hoddinott, Simon Lewin, Kate J. Thomas, Bridget Young, Joy Adamson, Yvonne Jfm Jansen, Nicola Mills, Graham Moore, Jenny L. Donovan, and et al. 2015. Maximising the impact of qualitative research in feasibility studies for randomised controlled trials: Guidance for researchers. Pilot and Feasibility Studies 1: 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandya, Samta P. 2018. Spirituality to build resilience in primary caregiver parents of children with autism spectrum disorders: A cross-country experiment. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities 64: 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, Myriam Cielo, Dinesh Chandra, Georges Koné, Rohit Singh, Valery Ridde, Marie-Pierre Sylvestre, Aaditeshwar Seth, and Mira Johri. 2020. Implementation fidelity and acceptability of an intervention to improve vaccination uptake and child health in rural India: A mixed methods evaluation of a pilot cluster randomized controlled trial. Implementation Science Communications 1: 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochon, Justine, Matthias Gondan, and Meinhard Kieser. 2012. To test or not to test: Preliminary assessment of normality when comparing two independent samples. BMC Medical Research Methodology 12: 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, Mamta, and Regina Giraldo-García. 2018. The Role of Parental Involvement and Social/ Emotional Skills in Academic Achievement: Global Perspectives. School Community Journal 28: 29–46. [Google Scholar]

- Scher, Benjamin D., Juliet Scott-Barrett, Matthew Hickman, and Benjamin W. Chrisinger. 2023. Participatory Research Emergent Recommendations for Researchers and Academic Institutions: A Rapid Scoping Review. Journal of Participatory Research Methods 4: 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singal, Nidhi. 2016. Schooling children with disabilities: Parental perceptions and experiences. International Journal of Educational Development 50: 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skivington, Kathryn, Lynsay Matthews, Sharon Anne Simpson, Peter Craig, Janis Baird, Jane M Blazeby, Kathleen Anne Boyd, Neil Craig, David P French, Emma McIntosh, and et al. 2021. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: Update of Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 374: n2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, James, Onno van der Groen, and Yvonne Learmonth. 2023. Feasibility Meets Implementation Science: Narrowing the Research-To-Practice Gap for Exercise Activity in Multiple Sclerosis. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smythe, Tracey, Nihad A. Almasri, Marisol Moreno Angarita, Brad D. Berman, Olaf Kraus de Camargo, Mijna Hadders-Algra, Paul Lynch, Maureen Samms-Vaughan, and Bolajoko O. Olusanya. 2022. The Role of Parenting Interventions in Optimizing School Readiness for Children With Disabilities in Low and Middle Income Settings. Frontiers in Pediatrics 10: 927678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smythe, Tracey, Veronika Reichenberger, Elisa María Pinzón, Isabel Cristina Hurtado, Luisa Rubiano, and Hannah Kuper. 2023. The feasibility of establishing parent support groups for children with congenital Zika syndrome and their families: A mixed-methods study. Wellcome Open Research 6: 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stacer, Melissa J., and Robert Perrucci. 2013. Parental Involvement with Children at School, Home, and Community. Journal of Family and Economic Issues 34: 340–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teresi, Jeanne A., Xiaoying Yu, Anita L. Stewart, and Ron D. Hays. 2022. Guidelines for Designing and Evaluating Feasibility Pilot Studies. Medical Care 60: 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNCRPD. 2006. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and Optional Protocol. New York: United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. 2018. Education and Disability: Analysis of Data from 49 Countries. Paris: UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. 2021. Seen, Counted, Included: Using Data to Shed Light on the Well-Being of Children with Disabilities—UNICEF DATA. UNICEF. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/resources/children-with-disabilities-report-2021/ (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Vaughn, Lisa M., and Farrah Jacquez. 2020. Participatory Research Methods—Choice Points in the Research Process. Journal of Participatory Research Methods 1: 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Yongli, Qin Wan, Zhaoming Huang, Li Huang, and Feng Kong. 2017. Psychometric Properties of Multi-Dimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support in Chinese Parents of Children with Cerebral Palsy. Frontiers in Psychology 8: 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washington Group. 2020. The Washington Group Short Set on Functioning (WG-SS). Available online: http://www.washingtongroup-disability.com/ (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Wondim, Mebrat G., Dawit Asrat Getahun, and Dawit Negassa Golga. 2021. Parental involvement in the education of their children with disabilities in primary schools of Bahir Dar, Ethiopia: Do education, income and employment status matter? Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs 21: 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz Bodur, Zeynep Yilmaz, and Sumer Aktan. 2021. A Research on the Relationship between Parental Attitudes, Students’ Academic Motivation and Personal Responsibility. International Journal on Social and Education Sciences (IJonSES) 3: 636–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimet, Gregory D., Nancy W. Dahlem, Sara G. Zimet, and Gordon K. Farley. 1988. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. Journal of Personality Assessment 52: 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuurmond, Maria, Gifty Nyante, Marjolein Baltussen, Janet Seeley, Jedidia Abanga, Tom Shakespeare, Martine Collumbien, and Sarah Bernays. 2019. A support programme for caregivers of children with disabilities in Ghana: Understanding the impact on the wellbeing of caregivers. Child: Care, Health and Development 45: 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Parents/Caregivers (n = 13) | Teachers (n = 4) | Local Leaders (n = 4) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 11 Female 2 Male | 4 Female 0 Male | 3 Female 1 Male |

| Age Range (years) | Range: 20–73 Mean: 42.9 (SD: 13.4) | Range: 30–49 Mean: 38.3 (SD: 8.3) | Range: 30–62 Mean: 50.5 (SD: 12.5) |

| Marital Status | 9 Married/Living together (69%) 3 Widowed (23%) 1 Single (8%) | 3 Married/Living Together (75%) 1 Divorced (25%) | 2 Married/Living Together (50%) 2 Widowed (50%) |

| Education Level | 7 Primary Incomplete (54%) 3 Primary Complete (23%) 3 Secondary Incomplete (23%) | 4 More than Secondary (100%) | 2 Secondary Incomplete (50%) 2 Secondary Complete (50%) |

| Occupation | 8 Self-employed (62%) 4 Unemployed (31%) 1 Student (8%) | 4 Employed (100%) | 2 Self-employed (50%) 1 Agriculture (25%) 1 Unemployed (25%) |

| Household Size | Range: 3–10 Mean: 6.9 (SD: 2.1) | Data not collected | Data not collected |

| Children’s age (years) | Range: 6–15 Mean: 11.5 (SD: 2.4) | Data not collected | Data not collected |

| Child’s Disability | 5 Physical (38%) 4 Hearing (31%) 4 Visual (31%) | N/A | N/A |

| Outcome | Pre-Intervention Mean (SD) | Post-Intervention Mean (SD) | Mean Difference (95% CI) | p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAFAS Parenting Practices | ||||

| Parental Consistency | 8.62 (1.76) | 1.58 (0.49) | 7.03 (5.82 to 8.25) | <0.001 |

| Coercive Parenting | 6.15 (3.05) | 1.28 (0.42) | 4.88 (2.97 to 6.78) | <0.001 |

| Positive Encouragement | 1.46 (1.05) | 0.03 (0.09) | 1.44 (0.84 to 2.03) | <0.001 |

| Parent–Child Relationship | 3.85 (1.28) | 0.03 (0.08) | 3.82 (3.03 to 4.6) | <0.001 |

| PAFAS Family Adjustment | ||||

| Parent Adjustment | 3.23 (1.48) | 0.58 (0.38) | 2.65 (1.91 to 3.38) | <0.001 |

| Family Relationships | 3.85 (2.85) | 0.81 (0.88) | 3.04 (1.53 to 4.55) | <0.001 |

| Parental Teamwork | 2.11 (1.54) | 0.62 (0.49) | 1.75 (0.6 to 2.9) | 0.009 |

| Outcome | Pre-Intervention Mean (SD) | Post-Intervention Mean (SD) | Mean Difference (95% CI) | p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) | ||||

| Significant Other Subscale | 4.02 (1.46) | 5.38 (0.49) | 1.37 (0.51 to 2.22) | 0.005 |

| Family Subscale | 3.21 (1.31) | 4.21 (1.3) | 1 (0.27 to 1.73) | 0.011 |

| Friends Subscale | 3.48 (1.42) | 5.35 (0.76) | 1.87 (1.04 to 2.69) | <0.001 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Musendo, D.J.; Polack, S.; Chirwa, B.; Nkambule, E.S.; Mukakagame, C.; Chikanya, M.; Nkhonjera, T.A.; Smythe, T. Feasibility of Tiyanjane: A Family–School–Community Intervention Promoting Parental Involvement in the Education of Children with Disabilities in Malawi. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 265. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14050265

Musendo DJ, Polack S, Chirwa B, Nkambule ES, Mukakagame C, Chikanya M, Nkhonjera TA, Smythe T. Feasibility of Tiyanjane: A Family–School–Community Intervention Promoting Parental Involvement in the Education of Children with Disabilities in Malawi. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(5):265. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14050265

Chicago/Turabian StyleMusendo, David John, Sarah Polack, Blessings Chirwa, Ellen S. Nkambule, Claire Mukakagame, Magnolia Chikanya, Thomas A. Nkhonjera, and Tracey Smythe. 2025. "Feasibility of Tiyanjane: A Family–School–Community Intervention Promoting Parental Involvement in the Education of Children with Disabilities in Malawi" Social Sciences 14, no. 5: 265. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14050265

APA StyleMusendo, D. J., Polack, S., Chirwa, B., Nkambule, E. S., Mukakagame, C., Chikanya, M., Nkhonjera, T. A., & Smythe, T. (2025). Feasibility of Tiyanjane: A Family–School–Community Intervention Promoting Parental Involvement in the Education of Children with Disabilities in Malawi. Social Sciences, 14(5), 265. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14050265