Abstract

The experience of loneliness in old age has gained relevance for social gerontology due to its association with the adverse biopsychosocial health status of the elderly, significantly impacting quality of life in old age. Therefore, the objective of this study was to understand the experiences of loneliness, analysing the perception of its risk and protective factors, as well as the coping strategies used by older people in Chile and Spain, through a transnational qualitative approach, with a view to identifying the influence of cultural variables in the presence of this problem. This research was a descriptive study which used qualitative methodologies for data collection and analysis. The research participants were 30 older people of both sexes who participated in a semi-structured interview about their experiences of loneliness. The main results showed that loneliness in old age was experienced as an emotional disconnection and lack of intimacy and company, mainly in family relationships. Among the most prominent risk factors were old age, gender roles, widowhood, economic limitations, and loss of autonomy. Protective factors included active social participation, religious practice, and participation in meaningful social activities. As for coping strategies, these ranged from strengthening relationships to using digital tools and accepting loneliness as part of life. The findings of this study underline the importance of designing interventions focused on social inclusion and subjective well-being in old age, which contribute to preventing the experience of loneliness at this stage of the life cycle.

1. Introduction

In recent decades, the study of loneliness has gained special relevance in the evolutionary phase of old age because it can be associated with serious consequences for the physical and mental health of those who experience it, which can cause high rates of hospitalisation and social isolation, affecting the subjective well-being of older people (Courtin and Knapp 2017; WHO 2021). Scientific evidence has reflected an increase in the prevalence of this problem globally, which is associated with high morbidity and mortality rates, and is currently considered a serious public health problem (Holt-Lunstad et al. 2015; Lorente-Martínez 2017; WHO 2021; Yanguas et al. 2020).

The experience of loneliness has been described as a situation perceived by the individual as an unpleasant or inadmissible lack of quality in certain social relationships, including cases where the number of existing relationships is lower than what is considered desirable or admissible, or where the desired level of intimacy has not been reached (de Jong Gierveld 1987). It involves an unpleasant emotional state related to the deficient nature of one’s interpersonal relationships (Peplau and Perlman 1982).

Older people perceive loneliness as a state of affective insufficiency in their relationships with significant others, mainly with members of the family group (Sánchez-Moreno et al. 2025). Empirical evidence confirms that the presence of a network of intimate relationships provides cohesion and a sense of belonging, being a protective factor for the experience of loneliness due to the exchange of support resources within the network (de Jong Gierveld 1998; Goldman and Cornwell 2018; Hogerbrugge and Silverstein 2015).

In reference to the subjective experiences of loneliness in old age, Yanguas (2018) suggest that they are expressed in various ways in older people, which can include social isolation, the presence of emotions of abandonment, helplessness and rejection, existential boredom, fear, threats about the future, shame, and social dysfunction. The above findings demonstrate the negative emotional nature of this problem, which affects older adults’ subjective well-being.

Due to the impact that the experience of loneliness has on the quality of life, subjective well-being, and health status of the elderly, one of the central objectives in the study of this problem has been to focus on analysing its predictive factors; there is a broad line of research on the subject that distinguishes between protective and risk factors, which would help to explain their possible determinants and developmental courses (Yanguas et al. 2020; de Jong Gierveld et al. 2018; Newall et al. 2009).

In this way, through different studies, it can be found that the experience of loneliness in old age is related to different sociodemographic, personal, social, and cultural factors, all of which are in mutual interaction and would allow for the prediction of its prevalence (Dahlberg et al. 2022). Studies have observed the well-defined psychosocial nature of this problem, which is associated with factors such as gender, marital status, social networks, and the physical and mental health status of older people (Aartsen and Jylhä 2011; Cohen-Mansfield et al. 2016; de Jong Gierveld 1998; Yanguas 2018).

Although the experience of loneliness is a phenomenon with a greater probability of occurring in old age due to the changes occurring with age, this is not a particular problem for this developmental stage; a greater predominance of the problem is observed in those older people who present a greater functional dependence, which alters their social functioning and active participation in social relationships (Dahlberg et al. 2022). In this way, such a negative experience can be prevented and/or intervened in early through the consideration of the social participation of subjects in previous stages of life (WHO 2021).

This requires positioning older people as active agents in the promotion of their state of health, quality of life, and social integration, through the consolidation of lifestyles that reinforce protective factors for their development and that contribute to the consolidation of healthy social interactions, all of which influence the promotion of positive ageing processes and the prevention of experiences of loneliness (Fernández-Ballesteros 2009; Gallardo-Peralta 2019; Victor et al. 2022; Yanguas et al. 2020).

In relation to the latter, recent research on the experience of loneliness in older people has focused on the coping strategies that subjects use to manage this experience, promoting their psychological well-being through individual and social resources (Celdrán and Martínez 2020; Herrera et al. 2018). These strategies include active mechanisms such as seeking social support and participation in community activities, as well as cognitive strategies that help to reinterpret the experience of loneliness in a more positive way (Kharicha et al. 2018). On the other hand, older people with fewer social resources or low self-esteem tend to employ regulatory strategies, such as lowering their expectations about relationships, which can make it difficult to cope effectively (Schoenmakers et al. 2012).

At present, there is an important debate on the influence of cultural variables on the development of the problem, through which it is postulated that the presence of loneliness in older people would be the product of cultural values such as social mobility and the decrease in interpersonal contact, which affect the consolidation of satisfactory social relationships. In addition, the presence of individualistic values, success, and competition present in Western societies fosters the presence of loneliness by influencing styles of social interaction based on individual success (Cohen-Mansfield et al. 2016). In this way, current research on this problem should adopt a cross-cultural approach, which allows for findings to be obtained that can be generalised to different sociocultural contexts (de Jong Gierveld et al. 2018; WHO 2021; Valtorta et al. 2016).

There has been an extensive line of research in recent decades examining the issue of loneliness among older adults (Dahlberg et al. 2022; Patil and Braun 2024). The phenomenon is normally examined using a quantitative approach, whether focused on prevalence, protective/risk factors, consequences, or elsewhere. There is currently considerable debate over the research methodologies that should be used when examining the nature of a construct that is subjective due to its emotional nature. Phenomenological and participative methodologies should be used that can capture the complexity of loneliness in old age (de Jong Gierveld et al. 2018; Victor et al. 2022).

The novelty of this study effectively lies in broadening the knowledge about loneliness in the elderly from their own experiences (López and Díaz 2018) and adds the value of being a transnational study in two geographical contexts that share a substantial increase in their ageing populations and are family-focused society and cultural structures; therefore, families articulate the social and cultural organisation (Cavallotti et al. 2024; Gallardo-Peralta et al. 2018). In this regard, from a qualitative perspective that seeks to capture the narratives of older Chilean and Spanish adults, the aim of this research is to understand loneliness in old age by analysing the following: (1) the perceptions of older adults regarding the associated risk and protective factors; (2) the coping strategies that older adults use to overcome this feeling.

2. Methods

2.1. Design

This research entailed a transversal and transnational qualitative descriptive study and hence used qualitative methodologies for data gathering and analysis. This work brought together two studies whose methodologies were the same but were carried out at different times, as will be explained below. On the one hand, there was study 1, entitled ‘La soledad en las personas mayores chilenas: Una conceptualización a través de factores biopsicosociales y las trayectorias de vida’, which was carried out in Chile; and on the other hand, there was study 2, entitled ‘Pensar las Soledades desde el Trabajo Social. Avances y Tensiones en la Atención a las Personas Mayores y a su Diversidad’, which was carried out in Spain.

2.2. Participants

The research participants were aged over 65 years, comprised both genders, and had no cognitive impairment. The transnational nature of the study entailed the production of two independent samples based on participant nationality.

The study 1 sample was made up of 15 older Chilean adults, comprising both genders, residing in the city of Arica in the far north of Chile. A convenience sample was used with snowball sampling. In study, 2, the sample was made up of older Spanish adults and also comprised 15 participants of both genders residing in the city of Barcelona in Spain. A convenience sample was used with snowball sampling. The fundamental characteristics of the total study sample are set out in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants.

2.3. Instrument

Semi-structured interview guidelines were designed and were mainly used to investigate the experience of loneliness in old age. The interview guidelines were made up of open questions, divided into three corresponding dimensions: (i) perceptions of loneliness in old age, through questions such as: What is loneliness for you? Do you think that all older adults experience loneliness in old age?; (ii) the factors associated with loneliness in old age, involving questions such as: Which situations can influence older adults experiencing loneliness in old age?; and (iii) coping strategies, through questions such as: How do you think you protect yourself, or have protected yourself in the past, against negative experiences of loneliness?

2.4. Procedure

Given the transnational approach of the study, two different fieldwork procedures were carried out. While study 1 was conducted during the year 2022, study 2 was conducted during the year 2023.

Study 1: The semi-structured interviews were conducted by online video call owing to the contact restrictions associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. In Chile, the restrictions on contact, especially with older people, were more extensive over time (Oppenheimer-Lewin et al. 2022) and even older people themselves preferred many actions—such as the interview—to be performed online. Initial telephone contact was made with community leaders, who were invited to participate and were provided with information about the aims and scope of the study. The interviews were conducted by members of the team with an average duration of 60 to 90 min.

Study 2: Personal interviews (face-to-face) were held in Barcelona, with participants able to choose between the Catalan and Spanish languages and to decide on the interview location. In nine cases, the interviews were conducted at participants’ homes, including one person living in a residential setting. The interviews were conducted in reserved spaces within social services facilities in the other six cases. The interviews had an average duration of 60 to 90 min.

The Ethics Committee of Complutense University, Madrid (Report CE_20211216-02), which approved the study with the Chilean sample, and the Bioethics Committee of the University of Barcelona (IRB00003099), approving the ethical aspects of the study with the Spanish sample. The participants signed an informed consent form in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration.

2.5. Data Analysis

The process of analysing the narratives obtained from the semi-structured interviews was carried out in parallel in Chile and Spain, with at least three researchers taking part in each process, and a triangulation was subsequently carried out given that the focus of both studies had a similar methodological basis and object of study: the experience of loneliness in the elderly. This was conducted following the spiral analysis process described by Creswell (2007). First, the data were organised by preparing the information collected in the various interviews. The recordings of the interviews were transcribed verbatim (for those conducted in Catalan, the language of the interview was maintained in the qualitative analysis) and then entered into the data analysis programme Atlas.ti (v.24). In the second step, manual open coding procedures were applied, allowing for the emergence of new categories and the identification of significant topics; as well as manual axial coding, facilitating links between categories and sub-categories to develop the understanding of the relationships and intersections between them; and manual selective coding, permitting theoretical integration and refinement. As the third step, a coding and categorisation process was carried out using the Atlas.ti software (v.24). Subsequently, the Chilean and Spanish teams discussed and reached agreements on the main themes that emerged from the stories, such as what participants understand about and what meaning they give to loneliness, what factors they associate with feeling lonely in old age, and what their main coping strategies are.

3. Results

3.1. Constructing Meaning Regarding Loneliness in Old Age

The analysis of the individual interviews shows that loneliness in old age is defined as a negative feeling which arises mainly from the unsatisfied need for affective closeness and accompaniment in people’s older years, being related to their main social networks, and, in particular, to their family group, and being associated mainly with the quality of relationships, rather than with the reduction in social networks.

“Loneliness it is have not family ties; that is loneliness for me, The link with family members”.(Gastón, 65 years old, Chilean)

“It’s hard to feel lonely if you’re surrounded by people, I don’t mean the physical presence of people, but being with people who accompany you, who you have a relationship with. (…) I mean, if you’re surrounded by people who have nothing to do with you, I don’t see it as having company. And if you’re surrounded by people who do have to do with you, and you feel lonely… Anyone who feels this way should ask themselves why”.(Jeroni, 78 years old, Spanish)

3.2. Perceptions of Risk and Protective Factors

According to the situations that could influence the presence of loneliness in old age, studies indicate that the problem is associated with various biopsychosocial factors that would explain its prevalence. These factors are explained below.

3.2.1. Associated Sociodemographic Factors

- Age:

Age is often a factor that increases loneliness, and is associated with social losses, deterioration of health, personality changes, and difficulties in adapting to old age.

“It’s getting harder and harder, because as you get older you change, and depending on the way you are, you’re more likely to feel lonely”.(Climent, 73 years old, Spanish)

“Sometimes, having people close to you makes you feel even more alone, because those people don’t care about you, because it’s not in their interests to talk to you; because older adults are boring, we are repetitive. And that is part of our ageing”.(Marianela, 70 years old, Chilean)

- Gender:

In terms of gender, there are diverse perceptions of the participants regarding experiences of loneliness that are directly related to gender roles. On the one hand, there are discourses that point to the male gender as being the most prone to loneliness. In addition, discourses are observed that point to a conditioning of gender roles in the autonomy of women in previous stages of life, so that loneliness in old age would be an opportunity for autonomy and freedom.

“Clearly there is a gender issue. I think men suffer more from loneliness than women, because they are less sociable and lose their friend group earlier, also because men generally have a hard time joining senior clubs; for example, because they associate everything around work; The groups of elderly people were associations of retirees. for them, the concept of group is more like a union than a social or community group”.(Edith, 70 years old, Chilean)

“Loneliness is the price of freedom. (…) As long as you have your husband and kids at home, you’re not free to do whatever you want. But when there is no one else at home but you, you can do whatever you want, period”.(Marcelina, 82 years old, Spanish)

- Marital status:

Marital status is described as a significant aspect in the experiences of loneliness, with differences observed in the narratives of the participants according to their marital status. In this sense, those widowed participants refer to widowhood as a cause of their emotional support network being limited and as a cause of loneliness. The single interviewees observe that singleness in old age is directly associated with loneliness due to lack of company. Finally, divorced people do not perceive the absence of a partner as a factor of loneliness.

“When she died, I broke down… I collapsed. I was depressed. It made me anxious. couldn’t handle it. Then I thought: This is not going to end well for me”.(Antoni, 87 years old, Spanish)

“I felt very lonely when my husband died and, well, although it is true that he was not at home every day; he worked outside, but when it came time to sit at the table and eat alone, with no one to share with, no one to talk to… I lost the desire for everything. What was the reason for cooking? The food didn’t matter anymore, I would eat anything… That is why we must try not to fall into depression; you have to look for support”.(Zaida, 65 years old, Chilean)

“I have been a follower of Plato all my life. And I believed in soulmates even before I read it. And in his idea of friendship… Plato said that two friends are just two separate bodies and one soul. There are those of us who yearn to find that reflection. He speaks of despair. And that’s where that loneliness comes from for me. (…) I thought: if there are people who have that soulmate, why not me?”.(Marcel, 66 years old, Spanish)

- Available Resources:

The availability of financial resources is perceived as a factor that conditions the way in which older people experience loneliness. In addition, economic constraints reduce opportunities to participate in activities that could alleviate loneliness, along with bringing unfavourable living conditions.

“I can’t choose how I age… I have no options”.(Juana, 76 years old, Spanish)

“I think that getting older is hard for many people, especially those who don’t have enough money, they lack, for example, guidance or ties to join an organisation, or something that helps them alleviate this loneliness”.(Ricardo, 72 years old, Chilean)

- Residential Settings:

Place of residence is identified as a factor influencing loneliness, although there are differing opinions about this.

People who live alone express satisfaction with the present, although they note that this situation could become a risk in the future. In addition, participants living in nursing homes cite a lack of empathy in their treatment and a sense of isolation.

“Being alone doesn’t mean you always want to be around people. By now, I’ve gotten used to it”.(Climent, 73 years old, Spanish)

“I have experience with people who live alone very happily, not isolated, but alone in their space, doing their own thing, going out to meet or receive visitors, and that is valuable; but stigmatised negatively, as something bad”.(Zaida, 74 years old, Chilean)

“If you grow old in your own home, I think the term “loneliness” is not so bad, because you have a son, a daughter, grandchildren who can be by your side. but in other circumstances, with residences for the elderly… of course they are impeccable places, with many nursing services, doctors, but you feel solo.la family visits you very occasionally, that is loneliness for me”.(Gastón, 65 years old, Chilean)

3.2.2. Factors Associated with Autonomy and Health

Autonomy and good physical and mental health are key elements for emotional well-being in old age and for managing loneliness. However, these variables are associated with the demands that people impose on themselves to maintain their functionality despite the limitations of age, affecting the way they seek support in the face of health-related difficulties.

Physical dependence and physical and cognitive impairment in old age are perceived by the participants as significant obstacles to daily activities and social interactions, increasing social isolation and experiences of loneliness and impacting their subjective well-being. On the other hand, critical health events, such as accidents and unexpected health problems, are mentioned as moments that intensified their perception of loneliness.

Finally, the characteristics of the residential environment are also observed as a factor associated with the functional capacity of the elderly, due to the risk that they interfere with mobility and movement, hindering both mobility within the home and contact with the outside world, which increases their dependence on family members or caregivers to perform daily tasks.

“Yes… I think it has an influence. For example, if you’re in poor health, some say, “I didn’t want to call you because I don’t want to bother you.” But sometimes friends show up with a cane, a walker and everything, and they might even laugh. But it influences according to the character of the person. For example, vocabulary… Before, my mother would say, “You have to be proud.” Today it is dignity”.(Sara, 74 years old, Chilean)

“I have had a left leg prosthesis for twenty-three years and a right leg prosthesis for two years. I can’t go out alone, so I don’t go out. If no one comes to look for me, I can’t go out”.(Augusta, 95 years old, Spanish)

“I want to do a lot of things, I think mentally I can do more, but physically I can’t. I’ve realised that I can move mountains with my mind, but physically I can’t, sometimes my wife has had to take me and I have had to depend on her to go and get vaccinated… I have a lumbar hernia… Sometimes you want to do it yourself, but you can’t. Sometimes I’ve been alone and I can’t go out; Then you feel lonely. That is the loneliness of old age”.(Mario, 81 years old, Chilean)

“Loneliness makes you feel like you’re missing things at certain times. (…) I fell out of bed and broke a vertebra. I was on the ground for hours until I got help. (…) When I fell out of bed and got stuck there, I realised that I was totally and absolutely alone”.(Paloma, 73 years old, Spanish)

“After the accident, I knew I couldn’t live here. These stairs have no space to put your feet”.(Juana, 76 years old, Spanish)

3.2.3. Associated Interpersonal Factors

- Social ties:

Transnational narratives reflect that the loss and weakening of social networks are associated with experiences of loneliness in old age, because they limit access to meaningful bonds. In addition, emotional distancing and the presence of conflicts in family relationships are also frequently associated with loneliness; feelings of abandonment are recurrent in the narratives.

“In some cases, people feel completely alone if they lose contact with their family, their grandchildren, their children. And then some! Older people today, when we started this process, said, “Well, my son doesn’t call me.” I told them: “But you have to call them”, right? No! “It’s the son”… No, I said: “Whoever loves it the most is the one who gets closer”.(Sara, 74, Chilean)

“I wish her happy birthday, she tells me ‘thank you, grandma’, but she never asks me how I am. That hurts a lot”.(Rosalinda, 84 years old, Spanish)

- Search for new social links:

Experiences of dissatisfaction in previous interpersonal relationships limit the construction of new bonds in old age, being associated with a weakening of social networks. In this way, a lack of stable relationships throughout life is mentioned as a factor that increases vulnerability to loneliness.

“I’ve never liked friendships. When I was young, there was always criticism and I got tired”.(Augusta, 95 years old, Spanish)

“It makes me think that sometimes young people don’t value friendship. I hope they don’t get old before valuing it, because friends have always been important in people’s lives”.(Edith, 70 years old, Chilean)

- Community Engagement:

A low level of participation in social or peer group activities is described as a factor that increases loneliness, due to its association with close social networks.

“Often there are four of us, the same as always. And there comes a point when you don’t feel like going to see what happens”.(Climent, 73 years old, Spanish)

“Just being with other people, getting together with other people, doesn’t make you feel so lonely. There is a closeness with the people”.(Gladys, 68 years old, Chilean)

3.3. Perceptions of Coping Strategies for Loneliness

- Use of audiovisual media:

The daily use of media such as television and radio is identified as a useful tool to mitigate the feeling of loneliness, offering a sense of company and contact with immediate reality, incorporating this feeling into daily routines.

“The radio accompanies me. I keep up and listen to people talk”.(Climent, 83 years old, Spanish)

“I love listening to radio shows. This afternoon I was at home doing things while listening to the radio. The last thing I do in bed is listen to the radio. I read it and then I play it until I fall asleep”.(Teresa, 68 years old, Spanish)

- Reading, music, and crafts:

Activities such as reading, music, and crafts are common strategies for facing loneliness, and are present in the daily lives of the participants.

“Music and books fill my life. Reading protects me from loneliness. (…) I also love sewing and doing crossword puzzles. It’s my medicine”.(Augusta, 95 years old, Spanish)

“Loneliness is in me, it’s something I fight against all the time. I don’t want to feel alone… I like to read, for example, I read a lot, I also write for that, and obviously my work”.(Marianela, 70 years old, Chilean)

- Religiosity:

Professing a religion is an important strategy for managing loneliness, as it involves feelings of love and companionship based on faith. Participating in worship spaces alongside other worshippers also provides seniors with distraction, alleviating the negative emotional experiences of loneliness.

“The only company that never lets you down is God. I pray two or three rosaries a day. (…) Loneliness does not weigh you down when God is by your side”.(Marcelina, 82 years old, Spanish)

“For example, a sermon in the morning, preparing for meetings in the afternoon. So, out of twelve hours, almost half is dedicated to activities… It would be different if you didn’t have any activity and spent twelve hours a day doing nothing or doing other things that don’t encourage you”.(Luis, 73 years old, Chilean)

- Technology and digitalisation:

The use of technology is also mentioned as a strategy to combat loneliness. In addition, the use of social networks such as YouTube and TikTok are also identified as forms of distraction and entertainment.

“I have digitised photos and videos of trips to keep myself busy and remember good times”.(Paloma, 73 years old, Spanish)

- Participation in daily activities:

Doing useful activities in daily life arises from the interviews as a key strategy to deal with loneliness, with participants organising their days based on plans.

“I go to Granollers for breakfast, and on Sundays I go to Tordera to spend the day. I do everything by train, first thing in the morning. What I have to do is not stay at home. Because that would be very hard”.(Rafel, 83 years old, Spanish)

“I believe, from my point of view as a Christian and writer, that if people do not continue to create or do not find reasons to create things, they will always feel alone”.(Sara, 74 years old, Chilean)

- Volunteering and social participation:

Volunteering and participation in social activities, such as senior clubs or social organisations, are identified as effective strategies to combat loneliness, mainly because of the company that enables interactions with peers or other people.

“With these things you fight loneliness. I have friends, on the phone, we go out for coffee”.(Antoni, 87 years old, Spanish)

“Groups are important for that, for the emotional support they provide, because going to the group allows people to escape from the reality they live as a family”.(Edith, 70 years old, Chilean)

- Finding a partner and companionship:

Finding a partner is also mentioned as a strategy to cope with loneliness, because the presence of an affective partner provides companionship.

“Since I was widowed, I thought I needed a partner”.(Antoni, 87 years old, Spanish)

“It is a situation that has affected many older people, and it is almost mandatory. You can pay for company. Money opens all doors”.(Marcel, 66 years old, Spanish)

- Acceptance of loneliness:

Some participants describe that they have learned to accept loneliness as part of life and as a way to adapt to different lifestyles. Participants emphasise that recognising loneliness is in itself a critical step in coping with it.

“I’ve had to accept it, because what happened to me also happens to a lot of people. I don’t give room to sad thoughts. You have to adapt to the circumstances and move forward”.(Augusta, 95 years old, Spanish)

“From my own experience, what you always repeat… Preparing for old age, accepting that at some point in your life you will depend on someone or something in particular, because it is not only about the context of the neighborhood, but about having glasses, hearing aids, a cane, because, well, a lot of loneliness and isolation occurs because people lose their hearing and then do not know how to use hearing aids. So in the end, people become more and more isolated, because sometimes I go and I hear a lot of noise and in the end I can’t intervene, I don’t know what they’re talking about, if they laugh, they might laugh at me and I don’t know… So that’s important”.(Edith, 70 years old, Chilean)

- Friendship:

Friendships are considered a key element in coping with loneliness in old age, as they offer intimacy, companionship, and pleasure.

“A lot of people go through our lives, but sometimes you keep a small group of people who go with you.” I think that allows us to deal with loneliness at any time of the month or week”.(Marianela, 70 years old, Chilean)

“A very important factor in life is to have friendship. I mean, you see eighty year olds people and they have friends, both male and female. So it really helps to cope with ageing… Having friends, being able to be with them, whether they are the same age or younger, allows you to enjoy life”.(Luis, 73 years old, Chilean)

“When you maintain bonds of friendship with people, you diminish or mitigate your feelings of loneliness”.(Gastón, 65 years old, Chilean)

- Intergroup and intergenerational contact:

Interaction with other social groups can be a strategy to cope with loneliness in old age, since it can expand the social networks of older adults.

“We have to integrate people, because if not, we work separately… Here are the young, the old, the women, the children and the sexual differences…. So change occurs through conversation, through daily interaction or in meetings, because not everyone is integrated; there are people who are happy in their corner, but then they feel alone, all those things”.(Sara, 74 years old, Chilean)

3.4. Summary of Results

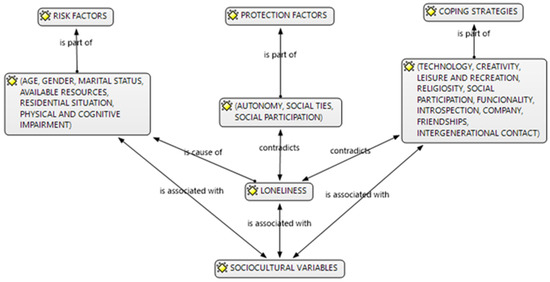

The results presented show that loneliness is a negative emotional experience in old age. It arises mainly from the unsatisfied need for closeness and affective companionship of older adults, in relation to their main social networks, and, in particular, to the family group. In addition, this emotional experience is strongly influenced by various sociodemographic and biopsychosocial variables, which act as risk and protective factors. However, various daily activities, relationships, and aspirations for participation were identified as strategies for coping with loneliness. An overview of these key findings is illustrated in Figure 1, which presents an integrated results model.

Figure 1.

Integrated results model.

4. Discussion

The findings show that the experience of loneliness is perceived as a negative emotional experience associated with emotionally disconnected interpersonal relationships, which refer to the family group, more than being associated with physical isolation, which coincides with much of the scientific literature on this construct (Gallardo-Peralta et al. 2024; Hutten et al. 2022), emphasizing the importance of the quality, rather than the quantity, of interpersonal relationships in preventing loneliness (de Jong Gierveld 1998; Peplau and Perlman 1982).

In this way, the importance of social ties involving affection and intimacy is highlighted, due to their protective role in the subjective well-being of older adults in both geographical contexts (Dahlberg et al. 2022; Goldman and Cornwell 2018; Hogerbrugge and Silverstein 2015).

In addition, based on the transnational nature of this research, the results show the presence of cultural nuances in the experience of loneliness in old age, which enrich the understanding of the phenomenon from a cultural perspective (de Jong Gierveld et al. 2018).

Chilean participants describe the experience of loneliness as being the result of external situations, such as the death of loved ones, family distance, or financial precariousness (Dahlberg et al. 2022). On the other hand, the Spanish participants perceive loneliness as a functional tool to guide the course of social ties, decision-making related to emotional well-being, and the rediscovery of personal autonomy. This perspective aligns with Cacioppo and Cacioppo’s (2018) Evolutionary Theory of Loneliness, which proposes that loneliness triggers self-protection mechanisms designed to enhance evolutionary fitness. In this sense, the introspective and self-exploratory use of solitude could be interpreted as an adaptive strategy that encourages the re-evaluation of unsatisfactory bonds and the search for more meaningful relationships, contributing to both emotional well-being and social cohesion in the long term.

Regarding the perception of risk factors associated with loneliness in old age, the results show that in both study samples, the problem is associated with various sociodemographic and biopsychosocial factors, such as age, gender, marital status, availability of resources, health autonomy, and interpersonal factors, which have been widely evidenced in the scientific literature on this construct; therefore, from the transnational perspective of this study, the influence of homogeneous risk factors in both cultural contexts is evident (Aartsen and Jylhä 2011; Cohen-Mansfield et al. 2016; de Jong Gierveld 1998; Victor et al. 2022; Yanguas 2018).

In reference to age, it is associated with an increase in loneliness through its association with accumulated losses and changes in personal adaptation. This coincides with the main literature about this theme, which identifies age as a determinant of loneliness throughout life and links ageing with vital changes defined by relational and physical loss (Dykstra 2009; Lasgaard et al. 2016; Pinquart and Sorensen 2001).

Regarding gender as a factor associated with loneliness in old age, it is observed that men are perceived as being more vulnerable to social loneliness, due to the construction of more limited social networks throughout life, which increases the risk of loneliness when these networks are reduced (Borys and Perlman 1985; Nicolaisen and Thorsen 2014). In addition, some women experience emotional disconnection after family losses or conflicts, but describe loneliness as an opportunity to redefine their autonomy and personal well-being. This finding reflects the gender differences in terms of the experiences of loneliness in old age, which are associated with the meaning that the subjects attribute to the problem of loneliness, with our study observing that women reframe their experience of emotional loneliness as a space for introspection and personal growth (Celdrán 2021).

With respect to marital status, singleness or widowhood are presented as particularly critical factors for experiences of loneliness, due to the lack of companionship and intimacy provided by a relationship. This is consistent with previous studies (Dahlberg et al. 2022; Victor et al. 2022). However, the interviews also reveal that divorce is associated with feelings of peace and freedom, due to the poor quality of the previous relationship (Rueda and De los Santos 2023).

The results reinforce previous findings on the association between the availability of economic resources and loneliness, as they link precarious economic income with the presence of the problem of loneliness, as it influences older people’s access to social networks which are focused mainly on the family, limiting spaces for interaction external to family dynamics (Cohen-Mansfield et al. 2016; Martín-Roncero and González-Rábago 2022; Sánchez-Moreno et al. 2025). On the other hand, Pinazo-Hernándis and Donio-Bellegarde Nunes (2018) suggest that people with greater financial resources tend to maintain more diversified networks, which acts as a protective factor against loneliness.

Health and autonomy are also identified as key elements for emotional well-being in old age, due to their impact on the functional capacity of older people to carry out their daily lives. The close relationship that older people establish between situations of dependency or a greater need for care and loneliness is consistent with numerous previous studies on this topic (Cohen-Mansfield et al. 2016; Hawkley and Kocherginsky 2018; Johnson 1983; Pinquart and Sorensen 2001).

In addition to interpersonal factors, the findings show that the quality and affective closeness of interpersonal relationships are key determinants of loneliness in old age. In this sense, the loss or weakening of significant social networks, such as family and friends, is directly associated with the experience of loneliness, especially when these connections are not replaced by new or satisfactory bonds (Burholt et al. 2020; Goldman and Cornwell 2018).

In reference to the coping strategies of the elderly to manage the experience of loneliness, the results show that the participants use proactive strategies to improve their emotional well-being, which include individual mechanisms, such as the use of audiovisual media, reading, and spirituality, and relational strategies, such as the search for social support and participation in community activities (Celdrán and Martínez 2020; Herrera et al. 2018). In addition, the use of technologies such as social networks and digital platforms reflects an intergenerational change in coping mechanisms, while volunteering and seeking companionship emerge as effective practices to reduce perceived loneliness (Kharicha et al. 2018; Schoenmakers et al. 2012).

In contrast to the above, some participants adopt a form of resigned acceptance of loneliness, particularly in contexts of physical or financial limitations, which underscores the importance of designing preventive and adaptive interventions that foster resilience and social participation (Cruwys 2023; Hamilton-West et al. 2020).

The findings reinforce the need to prioritise interventions that promote social interaction and foster the consolidation of strong and emotionally meaningful interpersonal bonds in old age. In this sense, although family relationships are essential to prevent and reduce loneliness in older people, it is also necessary to consolidate social relationships with peers, friends, and other significant figures to promote emotional well-being and strengthen the impact of protective factors that prevent loneliness at this stage of the life cycle (Ogrin et al. 2021).

In summary, the results obtained in this study allow us to understand the emotional impact of the experience of loneliness in old age, along with allowing us to identify the determining factors and coping strategies for the problem of loneliness according to the individual narratives of the participants. We manage to identify common variables of influence and coping strategies in both cultural contexts, which reinforce the psychosocial nature of the problem and the relevance of qualitative approaches to exploring, in depth, the subjectivity and complexity of the experience of loneliness in old age, which has been reported through existing scientific evidence (de Jong Gierveld et al. 2018; Victor et al. 2022).

Due to the accelerated ageing of the world’s population, future research should focus on analysing the resilience and adaptive capacity of older people to manage experiences of loneliness in old age, with a view to promoting successful ageing processes based on the Sustainable Development Goals for the 20–30s.

Author Contributions

P.A.F.-D., J.C.-M. and L.P.G.-P. contributed equally to all stages of the work, including conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, data interpretation, manuscript drafting, critical review, and editing. Data collection was primarily conducted by P.A.F.-D. in Chile and by J.C.-M. in Spain. Additionally, all authors have reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript and take full responsibility for its accuracy and integrity. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

JCM was funded by the FPU-grant FPU21/01738 from the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Complutense University, Madrid (protocol code CE_20211216-02) for the Chilean sample, and the Bioethics Committee of the University of Barcelona (protocol code IRB00003099) for the Spanish sample.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained in written form in both Chile and Spain prior to participation. However, the process extended beyond the mere act of signing a document. In both countries, participants were provided with a clear and comprehensive oral explanation of the study’s objectives, the nature and sensitivity of the topic, the voluntary nature of their participation, their right to withdraw at any time without consequence, and the measures taken to ensure their confidentiality and data protection. Particular attention was given to the emotional sensitivity of discussing experiences of loneliness in old age. Researchers ensured that participants had the time and space to ask questions, and confirmed their understanding before obtaining consent. In Chile, where interviews were conducted online due to pandemic-related restrictions, the consent form was sent in advance and then reviewed and confirmed orally before the interview began. In Spain, consent forms were reviewed and signed in person, with additional verbal explanations provided to ensure clarity and comfort.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the older adults who generously shared their experiences and to the local organisations and contacts in Arica and Barcelona who supported the participant recruitment process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funding sponsors had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Aartsen, Marja, and Marja Jylhä. 2011. Onset of Loneliness in Older Adults: Results of a 28-Year Prospective Study. European Journal of Ageing 8: 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borys, Sheila, and Daniel Perlman. 1985. Gender Differences in Loneliness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 11: 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burholt, Vanessa, Bethan Winter, Marja Aartsen, Costas Constantinou, Lena Dahlberg, Villar Feliciano, Jenny de Jong Gierveld, Sofie Van Regenmortel, and Charles Waldegrave. 2020. A Critical Review and Development of a Conceptual Model of Exclusion from Social Relations for Older People. European Journal of Ageing 17: 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo, John T., and Stephanie Cacioppo. 2018. Loneliness in the Modern Age: An Evolutionary Theory of Loneliness (ETL). In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Edited by James M. Olson. Cambridge: Academic Press, vol. 58, pp. 127–97. [Google Scholar]

- Cavallotti, Rita, Laia Pi Ferrer, and Rejina M. Selvam. 2024. Family Social Capital’s Impact on the Family Stress Model: A Cross-Sectional Spanish Study During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Comparative Family Studies 54: 232–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celdrán, Montserrat. 2021. Una mirada de gènere a l’envelliment. El cas de la soledat no desitjada. Ajuntament de Barcelona. Available online: https://ajuntament.barcelona.cat/dretssocials/sites/default/files/arxius-documents/soledat-article-monserrat-celdran-genere-envelliment.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2024).

- Celdrán, Montserrat, and Regina Martínez. 2020. La soledat en persones grans: Com fer-hi front des de la seva complexitat. Barcelona Societat. Revista de Coneixement i Anàlisi Social 25: 94–106. Available online: https://ajuntament.barcelona.cat/dretssocials/sites/default/files/revista/10_en_profundidad_celdran_bcn25_cat.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2024).

- Cohen-Mansfield, Jiska, Haim Hazan, Yaacov Lerman, and Vered Shalom. 2016. Correlates and Predictors of Loneliness in Older Adults: A Review of Quantitative Results Informed by Qualitative Insights. International Psychogeriatrics 28: 557–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Courtin, Emilie, and Martin Knapp. 2017. Social Isolation, Loneliness and Health in Old Age: A Scoping Review. Health & Social Care in the Community 25: 799–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, John W. 2007. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Cruwys, Tegan. 2023. Future Directions in Addressing Loneliness Among Older Adults. Advances in Psychiatry and Behavioral Health 3: 187–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlberg, Lena, Kevin J. McKee, Anna Frank, and Muna Naseer. 2022. A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Risk Factors for Loneliness in Older Adults. Aging & Mental Health 26: 225–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong Gierveld, Jenny. 1987. Developing and Testing a Model of Loneliness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 53: 119–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong Gierveld, Jenny. 1998. A Review of Loneliness: Concept and Definitions, Determinants and Consequences. Reviews in Clinical Gerontology 8: 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong Gierveld, Jenny, Theo van Tilburg, and Pearl A. Dykstra. 2018. Loneliness and Social Isolation: New Ways of Theorizing and Conducting Research. In The Cambridge Handbook of Personal Relationships. Edited by Anita L. Vangelisti and Daniel Perlman. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dykstra, Pearl A. 2009. Older Adult Loneliness: Myths and Realities. European Journal of Ageing 6: 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Ballesteros, Rocío. 2009. Envejecimiento activo: Contribuciones de la psicología. Madrid: Pirámide. [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo-Peralta, Lorena Patricia. 2019. Soledad en las personas mayores chilenas: Su implicancia en el envejecimiento con éxito. Paraninfo Digital 13: e30096. Available online: https://ciberindex.com/index.php/pd/article/view/e30096 (accessed on 3 May 2024).

- Gallardo-Peralta, Lorena Patricia, Ana Barrón, María Ángeles Molina-Martínez, and Rocío Schettini. 2018. Family and Community Support among Older Chilean Adults: The Importance of Heterogeneous Social Support Sources for Quality of Life. Journal of Gerontological Social Work 61: 584–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo-Peralta, Lorena Patricia, Joan Casas-Martí, and Paula Fernández-Dávila. 2024. Soledad(es) en las personas mayores: Avances y retos desde el trabajo social gerontológico. In Tratado general de trabajo social, servicios sociales y política social: Tomo I. Trabajo social. Edited by José Garcés Ferrer. Valencia: Tirant Humanidades, pp. 663–95. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=9598374 (accessed on 3 May 2024).

- Goldman, Alyssa W., and Benjamin Cornwell. 2018. Social Disadvantage and Instability in Older Adults’ Ties to Their Adult Children. Journal of Marriage and Family 80: 1314–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton-West, Kate, Alistair Milne, and Sarah Hotham. 2020. New Horizons in Supporting Older People’s Health and Wellbeing: Is Social Prescribing a Way Forward? Age and Ageing 49: 319–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkley, Louise C., and Marina Kocherginsky. 2018. Transitions in Loneliness Among Older Adults: A 5-Year Follow-Up in the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project. Research on Aging 40: 365–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, María Soledad, María Beatriz Fernández, and Carmen Barros. 2018. Estrategias de afrontamiento en relación con los eventos estresantes que ocurren al envejecer. Ansiedad y Estrés 24: 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogerbrugge, Martijn J. A., and Merril D. Silverstein. 2015. Transitions in Relationships with Older Parents: From Middle to Later Years. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B 70: 481–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt-Lunstad, Julianne, Timothy B. Smith, Mark Baker, Tyler Harris, and David Stephenson. 2015. Loneliness and Social Isolation as Risk Factors for Mortality: A Meta-Analytic Review. Perspectives on Psychological Science 10: 227–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutten, Elody, Ellen M. Jongen, Klasien Hajema, Robert A. C. Ruiter, Frans J. M. Hamers, and Anke E. Bos. 2022. Risk Factors of Loneliness Across the Life Span. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 39: 1482–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Colleen Leahy. 1983. Fairweather Friends and Rainy Day Kin: An Anthropological Analysis of Old Age Friendships in the United States. Urban Anthropology 12: 103–23. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40553002 (accessed on 8 May 2024).

- Kharicha, Kalpa, Jill Manthorpe, Steve Iliffe, Nuriye Kupeli, and Kate Walters. 2018. Strategies Employed by Older People to Manage Loneliness: Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies and Model Development. International Psychogeriatrics 30: 1767–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lasgaard, Mathias, Karina Friis, and Mark Shevlin. 2016. Where Are All the Lonely People? A Population-Based Study of High-Risk Groups Across the Life Span. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 51: 1373–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorente-Martínez, Raquel. 2017. La Soledad en la Vejez: Análisis y Evaluación de un Programa de Intervención en Personas Mayores que Viven Solas. Doctoral dissertation, Universidad Miguel Hernández de Elche, Alicante, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- López, Javier, and María Pilar Díaz. 2018. El Sentimiento de Soledad en la Vejez. Revista Internacional de Sociología 76: e085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Roncero, Unai, and Yolanda González-Rábago. 2022. Soledad No Deseada, Salud y Desigualdades Sociales a lo Largo del Ciclo Vital. Gaceta Sanitaria 35: 432–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newall, Nancy E., Judith G. Chipperfield, Rodney A. Clifton, Raymond P. Perry, Audrey U. Swift, and Joelle C. Ruthig. 2009. Causal Beliefs, Social Participation, and Loneliness among Older Adults: A Longitudinal Study. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 26: 273–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolaisen, Magnhild, and Kirsten Thorsen. 2014. Who Are Lonely? Loneliness in Different Age Groups (18–81 Years Old), Using Two Measures of Loneliness. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development 78: 229–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogrin, Rajna, Elizabeth V. Cyarto, Karra D. Harrington, Catherine Haslam, Michelle H. Lim, Xanthe Golenko, Matiu Bush, Danny Vadasz, Georgina Johnstone, and Judy A. Lowthian. 2021. Loneliness in Older Age: What Is It, Why Is It Happening and What Should We Do About It in Australia? Australasian Journal on Ageing 40: 202–07. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppenheimer-Lewin, Dafna, Maritza Ortega-Palavecinos, and Rodrigo Núñez-Cortés. 2022. Resilience in Older People During the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Chile: Perspective from the Social Determinants of Health. Revista Española de Geriatría y Gerontología 57: 264–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, Uday, and Kathryn L. Braun. 2024. Interventions for Loneliness in Older Adults: A Systematic Review of Reviews. Frontiers in Public Health 12: 1427605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peplau, Letitia Anne, and Daniel Perlman. 1982. Perspectives on Loneliness. In Loneliness: A Sourcebook of Current Theory, Research and Therapy. Edited by Letitia Anne Peplau and Daniel Perlman. New York: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Pinazo-Hernándis, Sacramento, and Mônica Donio-Bellegarde Nunes. 2018. La Soledad de las Personas Mayores: Conceptualización, Valoración e Intervención. Available online: https://www.euskadi.eus/contenidos/documentacion/doc_sosa_soledad_mayores/eu_def/fpilares-estudio05-SoledadPersonasMayores-Web.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2024).

- Pinquart, Martin, and Silvia Sorensen. 2001. Gender Differences in Self-Concept and Psychological Well-Being in Old Age: A Meta-Analysis. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B 56: P195–P213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueda, María Concepción, and Perla De los Santos. 2023. ¿Más Vale Solo/a? Motivaciones, Significados y Afrontamiento de la Soledad Elegida en la Vejez. Perspectivas Sociales 25: 43–66. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Moreno, Esteban, Lorena Patricia Gallardo-Peralta, Vicente Rodríguez-Rodríguez, Pablo de Gea Grela, and Sonia García Aguña. 2025. Unravelling the Complexity of the Relationship between Social Support Sources and Loneliness: A Mixed-Methods Study with Older Adults. PLoS ONE 20: e0316751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenmakers, Eric C., Theo G. van Tilburg, and Tineke Fokkema. 2012. Coping with Loneliness: What Do Older Adults Suggest? Aging & Mental Health 16: 353–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valtorta, Nicole K., Mona Kanaan, Simon Gilbody, Sara Ronzi, and Barbara Hanratty. 2016. Loneliness and Social Isolation as Risk Factors for Coronary Heart Disease and Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal Observational Studies. Heart 102: 1009–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victor, Christina R., Isla Rippon, Manuela Barreto, Claudia Hammond, and Pamela Qualter. 2022. Older Adults’ Experiences of Loneliness Over the Lifecourse: An Exploratory Study Using the BBC Loneliness Experiment. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics 102: 104740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). 2021. Aislamiento Social y Soledad Entre las Personas Mayores: Informe de Promoción. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240030749 (accessed on 19 May 2024).

- Yanguas, José Javier. 2018. Soledad y personas mayores. Valencia: Universidad Internacional de Valencia. Available online: https://www.universidadviu.com/sites/universidadviu.com/files/media_files/Informe%20soledad%20y%20personas%20mayores.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Yanguas, José Javier, Mercè Pérez-Salanova, María Dolores Puga, Francisco Tarazona, Antonio Losada, Montserrat Márquez, and Sacramento Pinazo. 2020. El Reto de la Soledad en las Personas Mayores; Fundación Bancaria “La Caixa”. Available online: https://solidaridadintergeneracional.es/files/biblioteca/documentos/reto-soledad.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).