Women’s Life Trajectories in Rural Timor-Leste: A Life History and Life Course Perspective on Reproduction and Empowerment

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Timor-Leste

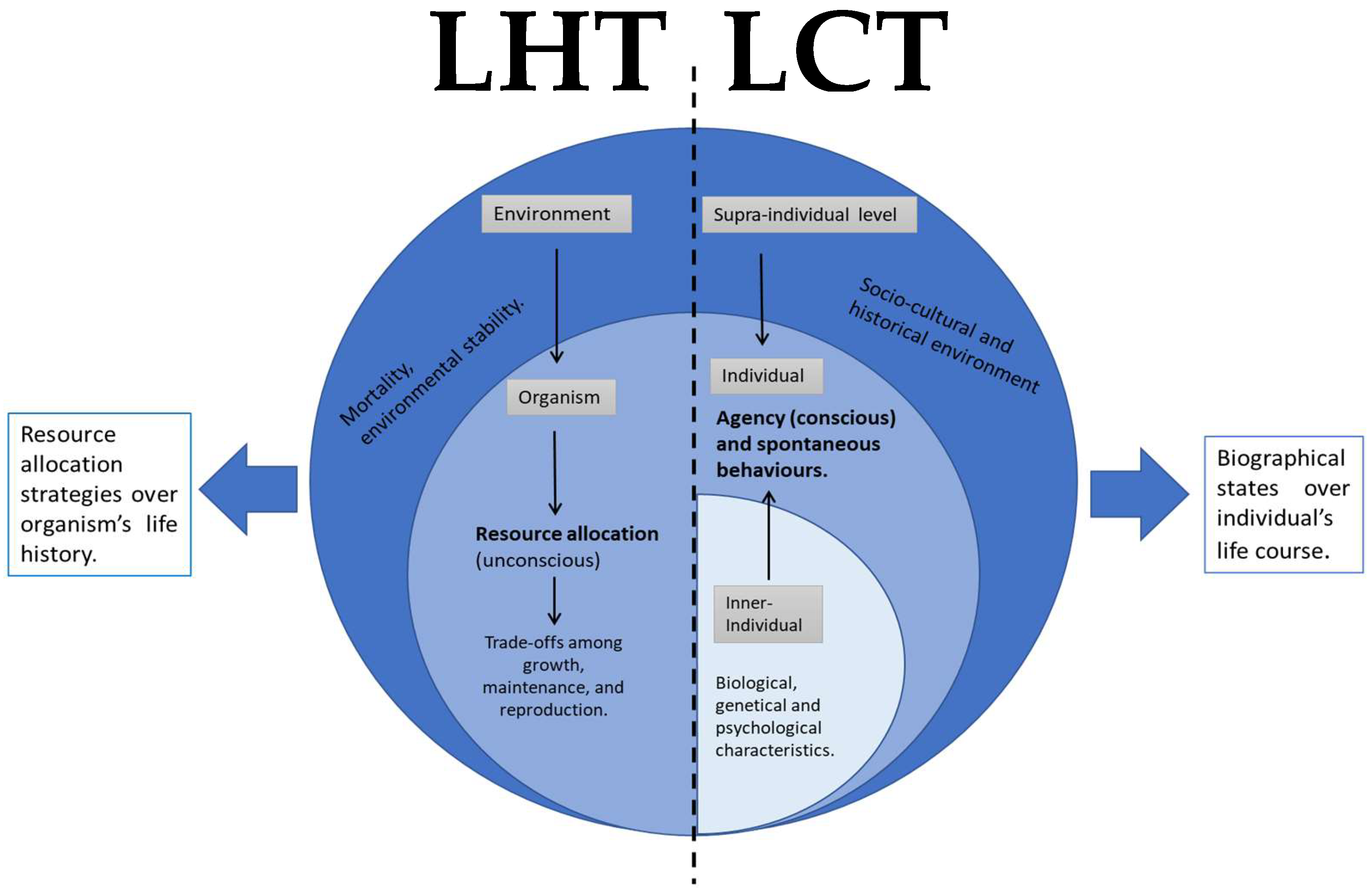

1.2. Life History Theory and Life Course Theory

1.3. Household Ecology and Women’s Empowerment

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Categorical Principal Components Analysis

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Health Status

2.2.2. Reproductive Outcomes: Age at First Birth, Births, and Child Deaths

2.2.3. Indicators of Women’s Empowerment: Family Planning, Education, and Income

2.2.4. Household Ecology Variables

- Subsidies. Introduced in 2008, the ‘Bolsa da mae’ is a governmental cash transfer for women who are mothers of school age children living in vulnerable households (Fernandes 2015). Women need to register at local health clinics to receive 5 USD per each child per month for up to three children (Fernandes 2015). Similarly to Bolsa da mae, Timor-Leste’s age pension was legislated in 2008 with the aim of providing 30 USD per month to any Timorese 60 years of age and older (Bongestabs 2016) who did not receive a veterans or employment pension. Both subsidies are included in the analysis as of 2018. Bolsa da mae is operationalised as receiving at least one by participating women (individual level) and age pension as the total number of pensions received by a particular household (household level). Few women receive pensions which are of a higher value (e.g., veteran pensions); therefore, they are not included in the analyses;

- Sanitation. The household’s type of sanitation was recorded in 2018 in 3 levels: having no facility, a traditional (pit latrine), or a developed facility (with an adjacent water tank or mandi). Based on the variable’s transformation plot after discretisation, we recategorized it into two categories for subsequent CATPCA iterations: having no facility and having a traditional or developed facility (Table 1);

- Water usage. Because water usage varies across communities, we use two different assessments: water supply in Ossu and water source in Natarbora. In Ossu, access to water is seasonal; therefore, water supply was initially categorised as spring, tap or pipe (bamboo canals) per each fieldwork year, and then the most common type of water supply across years was used for creating this variable. The variable was later recategorized into a binary variable (spring or tap, and pipe) based on the transformation plot after discretisation. In Natarbora, water source is measured in two categories: superficial (hand drawn from well, hand pump, or river) or deep source (sourced from a tank, an electric pump or piped water). We use water source data as of 2018;

- Livestock. Cattle ownership is assessed as the number of pigs and cows in the household reported by the respondent in 2018. Having pigs is measured as the total number of pigs and having cows as an ordinal variable with 3 levels: zero cows, between 0 to 10 and more than 10. Cows are recorded using these three categories during fieldwork as an estimate due to their extensive distribution in numbers. Respondents usually report “many” when they have high numbers of cows instead of providing an exact number;

- Garden plot (to’os). The existence of a to’os is assessed as a dichotomous variable. If the interviewee indicated that at least one crop was harvested in 2018 from a patch within their place of residence, the household was coded as having a garden plot;

- Electronics. We use two variables based on the effectiveness of electronics in reducing women’s household labour in the context of these rural communities. Labour-reducing electronics include rice cookers, sewing and washing machines, refrigerators, kettles, and mixers. Non-labour reducing electronics include light bulbs, telephone chargers, radios, music devices, televisions, electric saws, computers, irons, fans, photocopiers, motors, telephones, and internet cables. Both variables contribute to the total number of different appliances enumerated during the 2018 household interview. Only one item was counted when there were multiple of a particular category (i.e., light bulbs).

- Household residents. The number of people living in the household represents the total number of adults and children who typically sleep and eat in the household as recorded at interview.

2.2.5. Year of Birth (YOB) and Birth Region

| Variable | Collection Period | Measurement at Interview | Pre-CATPCA Operationalisation | Recategorization During CATPCA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health status a | Every visit | Healthy or unhealthy report | Ratio of reported good health to total years with valid data. | |

| Age at first birth b | Baseline | Year of first birth | Subtraction of first birth year minus woman’s year of birth. | |

| Births b | Every visit | No. of births | ||

| Child deaths b | Every visit | No. of child deaths and no. of still births. | Sum of child deaths and still births. | |

| Family planning c | Ossu: 2010, 2013, 2014, 2015 and 2018. Natarbora: 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015 and 2018. | Never used. Used medical method at least once. Using medical method Using non-medical method Used non-medical method | Evidence of use of family planning at least once across years or no evidence of use. | |

| Education d | Baseline | None Some or complete primary Some or complete SMP Some SMA/SPP until tertiary | Ossu: Under SMP and Some SMP to Tertiary Natarbora: Until complete SMP and SMA to Tertiary. | |

| Income c | Every visit | Having no income Selling non-animal/agricultural goods Selling animal/agricultural goods Day labour Business Wage earnings | Evidence of having income at least once across years or no evidence of income. | |

| Bolsa da Mae c | Every visit | No. of subsidies received per household | Receiving at least one (per woman) or not receiving at all. | |

| Sanitation e | Every visit | None, traditional (pit latrine) or developed facility | No toilet Traditional or developed. | |

| Water supply c (Ossu) | Every visit | Spring, tap or pipe | Most common type of water supply across fieldwork years grouped as: spring, tap or pipe. | Spring or tap. Pipe. |

| Water source c (Natarbora) | Every visit | Hand drawn from well. Hand pump River Tank Electric pump Piped water | Superficial (hand drawn from well, hand pump and river), or deep source (tank, electric pump and piped water) | |

| Cows d | Every visit | 0 cows, between 0 to 10, or more than 10 | ||

| Pigs b | Every visit | No. of pigs | ||

| Garden plot c | Every visit | List of crops harvested | At least 1 crop harvested or none | |

| Non-labour-reducing Electronics b | Every visit | List of appliances | No. of different non-labour reducing electronics: light bulbs, telephone chargers, radios, music devices, televisions, electric saws, computers, irons, fans, photocopiers, motor, telephones, and internet cables | |

| Labour-reducing Electronics b | Every visit | List of appliances | No. of different labour-reducing electronics: rice cooker, sewing and washing machine, refrigerator, kettle, or mixer | |

| Age pension c | Every visit | No. of age pensions received by household | ||

| Residents b | Every visit | No. of adults and children sleeping and eating in household consistently. | ||

| Year of birth b | Baseline | Reported verbally or using id card. | ||

| Birth region d | Baseline | Reported town of birth | Birth region by altitude level: 0 to 250 m, between 251 m to 500 m and from 501 m onwards |

2.3. Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of Pre-CATPCA Variables Across Field Sites

3.2. CATPCA

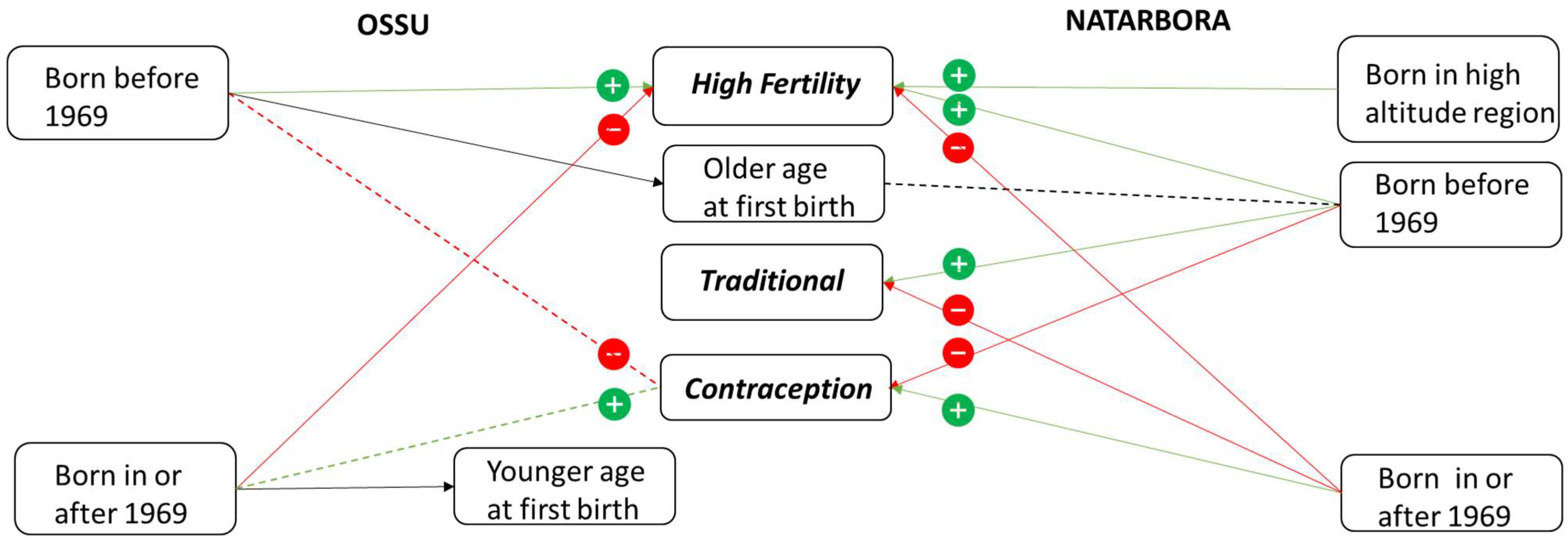

3.3. t-Tests: Birth Cohort and Birth Region

4. Discussion

4.1. Differences Between Communities: Health, Fertility, and Income

4.2. Women’s Profiles and Reproductive Timing

4.3. Tech and Sanitation: Wealth and Time Affluence

5. Conclusions

6. Policy Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agadjanian, Victor. 2023. The COVID-19 pandemic, social ties, and psychosocial well-being of middle-aged women in rural Africa. Socius 9: 23780231231171868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderman, Harold, Pierre-André Chiappori, Lawrence Haddad, John Hoddinott, and Ravi Kanbur. 1995. Unitary versus collective models of the household: Is it time to shift the burden of proof? The World Bank Research Observer 10: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AMSAT International. 2011. Fish and Animal Protein Consumption and Availability in Timor-Leste. National Directorate of Fisheries and Aquaculture Regional Fisheries Livelihoods Programme for South and Southeast Asia. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/an029e/an029e.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Atake, Esso-Hanam, and Pitaloumani Gnakou Ali. 2019. Women’s empowerment and fertility preferences in high fertility countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Women’s Health 19: 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, Gary S. 1965. A Theory of the Allocation of Time. The Economic Journal 75: 493–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, Gary S. 1981. Division of labor in households and families. In A Teatrise on the Family. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp. 19–44. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shlomo, Yoav, and Diana Kuh. 2002. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology: Conceptual models, empirical challenges and interdisciplinary perspectives. International Journal of Epidemiology 31: 285–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernardi, Laura, Johannes Huinink, and Richard A. Settersten. 2019. The life course cube: A tool for studying lives. Advances in Life Course Research 41: 100258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bongestabs, Andre F. 2016. Universal Old-Age and Disability Pensions Timor-Leste. Available online: https://www.social-protection.org/gimi/gess/RessourcePDF.action?ressource.ressourceId=54034 (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Bonis-Profumo, Gianna, Natasha Stacey, and Julie Brimblecombe. 2021. Measuring women’s empowerment in agriculture, food production, and child and maternal dietary diversity in Timor-Leste. Food Policy 102: 102102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvi, Rossella, Jacob Penglase, and Denni Tommasi. 2022. Measuring Women’s Empowerment in Collective Households. AEA Papers and Proceedings 112: 556–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Itelligence Agency. 2023. Timor-Leste. Available online: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/timor-leste/#people-and-society (accessed on 13 March 2024).

- Chisholm, James. 1993. “Death, Hope, and Sex: Life-History Theory and the Development of Reproductive Strategies” with CA comment. Current Anthropology 34: 1. [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm, James S. 1999. Death, Hope and Sex: Steps to an Evolutionary Ecology of Mind and Morality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Commission for Reception Truth and Reconciliation Timor-Leste. 2005. Chapter 7.7: Sexual Violence. In Chega! The Report of the Commission for Reception, Truth, and Reconciliation Timor-Leste. Available online: https://www.etan.org/news/2006/cavr.htm (accessed on 7 November 2024).

- Da Costa, Marcelino, Modesto Lopes, Anita Ximenes, Adelfredo do Rosario Ferreira, Luc Spyckerelle, Rob Williams, Harry Nesbitt, and William Erskine. 2013. Household food insecurity in Timor-Leste. Food Security 5: 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. 2019. Timor-Leste Country Brief. Available online: https://www.dfat.gov.au/geo/timor-leste/timor-leste-country-brief (accessed on 8 March 2019).

- Diener, Ed, and Eunkook Suh. 1997. Measuring Quality of Life: Economic, Social, and Subjective Indicators. Social Indicators Research 40: 189–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doepke, Matthias, and Michèle Tertilt. 2018. Women’s Empowerment, the Gender Gap in Desired Fertility, and Fertility Outcomes in Developing Countries. AEA Papers and Proceedings 108: 358–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, Frédéric. 2011. Three centuries of violence and struggle in East Timor (1726–2008). In Encyclopedia of Mass Violence. Paris: SciencesPo, vol. 1, p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, Rita. 2015. Assessing the Bolsa da Mãe Benefit Structure: A Preliminary Analysis. Available online: https://socialprotection.org/sites/default/files/publications_files/Bolsa%20da%20Mae%20Policy%20Note_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2024).

- Food and Agriculture Organization. 2011. The State of Food and Agriculture: Women in Agriculture, Closing the Gap for Development. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/i2050e/i2050e.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2024).

- Freitas Belo, Abílio António. 2015. Timor Leste government initiatives and civil society in contributing to the prevention of domestic violence. In Perspectivas e Trajetórias de Vida: Mulheres de Timor-Leste com Ensino Superior. Edited by Sarah Smith, Nuno Canas Mendes, Antero B. da Silva, Alarico da Costa Ximenes, Clinton Fernandes and Michael Leach. Melbourne: Swinburne Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gessert, Charles, Stephen Waring, Lisa Bailey-Davis, Pat Conway, Melissa Roberts, and Jeffrey VanWormer. 2015. Rural definition of health: A systematic literature review. BMC Public Health 15: 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilligan, Megan, Amelia Karraker, and Angelica Jasper. 2018. Linked Lives and Cumulative Inequality: A Multigenerational Family Life Course Framework. Journal of Family Theory Review 10: 111–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassi, Flavia, Josefine Landberg, and Sophia Huyer. 2015. Running Out of Time: The Reduction of Women’s Work Burden in Agricultural Production. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/i4741e/i4741e.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2024).

- Haddad, Lawrence, and Ravi Kanbur. 1992. Intrahousehold inequality and the theory of targeting. European Economic Review 36: 372–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrich, Joseph, Steven J. Heine, and Ara Norenzayan. 2010. The weirdest people in the world? The Behavioral and Brain Sciences 33: 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, Kim, and Hillard Kaplan. 1999. Life History Traits in Humans: Theory and Empirical Studies. Annual Review of Anthropology 28: 397–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeggi, Adrian V., Aaron D. Blackwell, Christopher von Rueden, Benjamin C. Trumble, Jonathan Stieglitz, Angela R. Garcia, Thomas S. Kraft, Bret A. Beheim, Paul L. Hooper, Hillard Kaplan, and et al. 2021. Do wealth and inequality associate with health in a small-scale subsistence society? eLife 10: e59437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jejeebhoy, Shireen J. 2002. Convergence and Divergence in Spouses’ Perspectives on Women’s Autonomy in Rural India. Studies in Family Planning 33: 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, Ian T., and Jorge Cadima. 2016. Principal component analysis: A review and recent developments. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 374: 20150202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabeer, Naila. 1999. Resources, Agency, Achievements: Reflections on the Measurement of Women’s Empowerment. Development and Change 30: 435–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, Hillard, Kim Hill, Jane Lancaster, and A. Magdalena Hurtado. 2000. A theory of human life history evolution: Diet, intelligence, and longevity. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews 9: 156–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, Snehendu B., Catherine A. Pascual, and Kirstin L. Chickering. 1999. Empowerment of women for health promotion: A meta-analysis. Social Science Medicine 49: 1431–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirk, Dudley. 1996. Demographic Transition Theory. Population Studies 50: 361–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzawa, Christopher W., and Jared M. Bragg. 2012. Plasticity in Human Life History Strategy. Current Anthropology 53: S369–S382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyweluk, Moira A., Alexander V. Georgiev, Judith B. Borja, Lee T. Gettler, and Christopher W. Kuzawa. 2018. Menarcheal timing is accelerated by favorable nutrition but unrelated to developmental cues of mortality or familial instability in Cebu, Philippines. Evolution and Human Behavior 39: 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, David W., and Ruth Mace. 2011. Parental investment and the optimization of human family size. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B. Biological Sciences 366: 333–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesthaeghe, Ron. 2010. The Unfolding Story of the Second Demographic Transition. Population and Development Review 36: 211–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Likhar, Akanksha, Prerna Baghel, and Manoj Patil. 2022. Early Childhood Development and Social Determinants. Cureus 14: e29500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linting, Mariëlle, and Anita van der Kooij. 2012. Nonlinear Principal Components Analysis With CATPCA: A Tutorial. Journal of Personality Assessment 94: 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linting, Mariëlle, Jacqueline J. Meulman, Patrick J. F. Groenen, and Anita J. van der Koojj. 2007. Nonlinear principal components analysis: Introduction and application. Psychological Methods 12: 336–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loney, Hannah. 2015. ‘The Target of a Double Exploitation’: Gender and Nationalism in Portuguese Timor, 1974–75. Intersections (Perth, W.A.). Available online: http://intersections.anu.edu.au/issue37/loney.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Lopes, Modesto, and Harry Nesbitt. 2012. Improving food security in Timor-Leste with higher yield crop varieties. Paper presented at 56th AARES Annual Conference, Fremantle, Australia, February 7–10. [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg, Shelly, and Robert A. Pollak. 1993. Separate Spheres Bargaining and the Marriage Market. The Journal of Political Economy 101: 988–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health. 2018. Timor-Leste Demographic and Health Survey 2016. Dili: GDS. Rockville: ICF. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, Gita D., Diana Kuh, and Rebecca Hardy, eds. 2023. A Life Course Approach to Women’s Health, 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, Incorporated, pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, Gita D., Rachel Cooper, and Diana Kuh. 2010. A life course approach to reproductive health: Theory and methods. Maturitas 65: 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narciso, Vanda Jesus Santos, and Pedro Damião Sousa Henriques. 2020. Does the matrilineality make a difference? Land, kinship and women’s empowerment in Bobonaro district, Timor-Leste. Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy 25: 348–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, Sarah, Nicole Stone, and Roger Ingham. 2016. The impact of armed conflict on adolescent transitions: A systematic review of quantitative research on age of sexual debut, first marriage and first birth in oung women under the age of 20 years. BMC Public Health 16: 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niner, Sara Louise, and Hannah Loney. 2020. The Women’s Movement in Timor-Leste and Potential for Social Change. Politics Gender 16: 874–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odongkara Mpora, Beatrice, Thereza Piloya, Sylvia Awor, Thomas Ngwiri, Paul Laigong, Edison A. Mworozi, and Ze’ev Hochberg. 2014. Age at menarche in relation to nutritional status and critical life events among rural and urban secondary school girls in post-conflict northern Uganda. BMC Women’s Health 14: 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Panter-Brick, Catherine. 1989. Motherhood and subsistence work: The tamang of rural Nepal. Human Ecology: An Interdisciplinary Journal 17: 205–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prata, Ndola, Ashley Fraser, Megan J. Huchko, Jessica D. Gipson, Mellissa Withers, Shayna Lewis, Erica J. Ciaraldi, and Ushma D. Upadhyay. 2017. Women’s empowerment and family planning: A review of the literature. Journal of Biosocial Science 49: 713–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reghupathy, Nadine, Debra S. Judge, Katherine A. Sanders, Pedro Canisio Amaral, and Lincoln H. Schmitt. 2012. Child size and household characteristics in rural Timor-Leste. American Journal of Human Biology 24: 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabageh, Adedayo Olukemi, Donatus Sabageh, Oluwatosin Adediran Adeoye, and Adeleye Abiodun Adeomi. 2015. Pubertal Timing and Demographic Predictors of Adolescents in Southwest Nigeria. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research 9: LC11-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samad, Nandeeta, Pranta Das, Segufta Dilshad, Hasan Al Banna, Golam Rabbani, Temitayo Eniola Sodunke, Timothy Craig Hardcastle, Ahsanul Haq, Khandaker Anika Afroz, Rahnuma Ahmad, and et al. 2022. Women’s empowerment and fertility preferences of married women: Analysis of demographic and health survey’2016 in Timor-Leste. AIMS Public Health 9: 237–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampson, Robert J., and John H. Laub. 1992. Crime and deviance in the life course. Annual Review of Sociology 18: 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sear, Rebecca, Paula Sheppard, and David A. Coall. 2019. Cross-cultural evidence does not support universal acceleration of puberty in father-absent households. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B. Biological Sciences 374: 20180124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeds of Life. 2007. Patterns of Food Consumption and Acquisition During the Wet and Dry Seasons in Timor-Leste: A Longitudinal Case Study Among Subsistence Farmers in Aileu, Baucau, Liquisa and Manufahi Districts. Available online: http://seedsoflifetimor.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/SOSEK-food-consumption-report-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2024).

- Seeman, Teresa E., Bruce S. McEwen, John W. Rowe, and Burton H. Singer. 2001. Allostatic Load as a Marker of Cumulative Biological Risk: MacArthur Studies of Successful Aging. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 98: 4770–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sell, Mila, and Nicholas Minot. 2018. What factors explain women’s empowerment? Decision-making among small-scale farmers in Uganda. Women’s Studies International Forum 71: 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellen, Daniel W., and Ruth Mace. 1997. Fertility and mode of subsistence: A phylogenetic analysis. Current Anthropology 38: 878–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharaunga, Stanley, Maxwell Mudhara, and Ayalneh Bogale. 2016. Effects of ’women empowerment’ on household food security in rural KwaZulu-Natal province. Development Policy Review 34: 223–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silove, Derrick, Belinda Liddell, Susan Rees, Tien Chey, Angela Nickerson, Natalino Tam, Anthony B. Zwi, Robert Brooks, Lazaro Lelan Sila, and Zachary Steel. 2014. Effects of recurrent violence on post-traumatic stress disorder and severe distress in conflict-affected Timor-Leste: A 6-year longitudinal study. The Lancet Global Health 2: e293–e300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, Kate, Davod Ahmadigheidari, Diana Dallmann, Meghan Miller, and Hugo Melgar-Quiñonez. 2019. Rural women: Most likely to experience food insecurity and poor health in low- and middle-income countries. Global Food Security 23: 104–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, Kitae. 2017. The Null Relation between Father Absence and Earlier Menarche. Human Nature 28: 407–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, Phoebe R. 2018. Child Growth Under Adverse Conditions: An Ecological Investigation of the Community, Household and Individual-Level Influences on the Growth Trajectories of Rural East Timorese Children. Perth: The University of Western Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, Phoebe R., and Debra S. Judge. 2021. Relationships of Resource Strategies, Family Composition, and Child Growth in Two Rural Timor-Leste Communities. Social Sciences 10: 273. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, Phoebe R., Katherine A. Sanders, and Debra S. Judge. 2018. Rural Livelihood Variation and its Effects on Child Growth in Timor-Leste. Human Ecology 46: 787–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stearns, Stephen C. 1989. Trade-Offs in Life-History Evolution. Functional Ecology 3: 259–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stulp, Gert, and Rebecca Sear. 2019. How might life history theory contribute to life course theory? Current Perspectives on Aging and the Life Cycle 41: 100281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumich, Chiara. 2015. Fertility Patterns in Rural Timor-Leste: Demographics Over Time and Space. Perth: The University of Western Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Sumich, Chiara. 2021. Characterisation of Social Networks in Rural Timor-Leste and an Investigation into Their Influence on Timorese Children’s Growth. Perth: The University of Western Australia. [Google Scholar]

- The Asia Foundation. 2016. Understanding Violence Against Women and Children of Timor-Leste: Findings from the Nabilan Baseline Study—Main Report. Boston: T. A. Foundation. Available online: https://asiafoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/UnderstandingVAWTL_main.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2024).

- Thu, Pyone Myat, and Debra S. Judge. 2017. Household agricultural activities and child growth: Evidence from rural Timor-Leste. Geographical Research 55: 144–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tribess, Camila, Cláudia Kreidloro, Ethiana Sarachin, Gabriela Batista, Juliana Santiago, and Vanessa Diniz. 2015. Perspectivas e trajetórias de vida: Mulheres de Timor-Leste com ensino superior. In Timor-Leste: Iha Kontextu Local, Rejional No Global. Edited by Sarah Smith, Nuno Canas Mendes, Antero B. da Silva, Alarico da Costa Ximenes, Clinton Fernandes and Michael Leach. Melbourne: Swinburne Press, pp. 106–11. [Google Scholar]

- Trivers, Robert L. 1972. Parental investment and sexual selection. In Sexual Selection and the Descent of Man, 1871–1971. Edited by Bernard Campbell. Chicago: Aldine, pp. 136–79. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Population Fund. 2024. UNFPA Timor-Leste. Available online: https://www.unfpa.org/data/TL (accessed on 13 July 2024).

- Upadhyay, Ushma D., Jessica D. Gipson, Mellissa Withers, Shayna Lewis, Erica J. Ciaraldi, Ashley Fraser, Megan J. Huchko, and Ndola Prata. 2014. Women’s empowerment and fertility: A review of the literature. Social Science Medicine 115: 111–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van de Kaa, Dirk J. 2004. Is the Second Demographic Transition a useful research concept: Questions and answers. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research 1: 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, Heather Julie, Susan McDonald, Suzanne Belton, Agueda Isolina Miranda, Eurico Da Costa, Livio Da Conceicao Matos, Helen Henderson, and Angela Taft. 2018. What influences a woman’s decision to access contraception in Timor-Leste? Perceptions from Timorese women and men. Culture, Health and Sexuality 20: 1317–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayte, Kayli, Anthony B. Zwi, Suzanne Belton, Joao Martins, Nelson Martins, Anna Whelan, and Paul M. Kelly. 2008. Conflict and Development: Challenges in Responding to Sexual and Reproductive Health Needs in Timor-Leste. Reproductive Health Matters 16: 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Western, Mark, and Wojtek Tomaszewski. 2016. Subjective Wellbeing, Objective Wellbeing and Inequality in Australia. PLoS ONE 11: e0163345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Haoyang, Li Chung Hu, and Emily Hannum. 2023. Youth educational mobility and the rural family in China. Research in Education. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable Code, Label | Ossu | Natarbora | p ** | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valid | Missing | Mode | (SD)/% | Valid | Missing | Mode | (SD)/% | ||

| Health ratio | 116 | 0 | 1 | 0.78 (0.29) | 140 | 0 | 1 | 0.61 (0.33) | p < 0.001 |

| Age at first birth | 105 | 11 | 22 | 22.29 (4.13) | 140 | 0 | 22 | 22.11 (4.66) | p = 0.765 |

| Births | 116 | 0 | 4 | 5.37 (2.45) | 140 | 0 | 1 | 4.17 (2.46) | p < 0.001 |

| Child deaths | 116 | 0 | 0 | 0.75 (1.19) | 140 | 0 | 0 | 0.26 (0.55) | p < 0.001 |

| Family planning 0 No evidence 1 Used at least once | 116 | 0 | 0 | 70.70% 29.03% | 140 | 0 | 0 | 67.9% 32.1% | p = 0.625 |

| Education 0 None 1 Some or complete primary 2 Some or complete SMP 3 Some SMA/SPP until tertiary | 82 | 34 | 0 | 37.8% 20.7% 23.2% 18.3% | 140 | 0 | 0 | 35.5% 19.4% 22.6% 22.6% | p = 0.919 |

| Income 0 No 1 At least once | 116 | 0 | 0 | 52.6% 47.4% | 140 | 0 | 0 | 75% 25% | p < 0.001 |

| Bolsa da mae 0 No 1 At least one | 116 | 0 | 0 | 94% 6% | 140 | 0 | 0 | 68.6% 31.4% | p < 0.001 |

| Toilet 0 No toilet 1 Traditional 2 Developed | 116 | 0 | 2 | 20.7% 3.2% 67% | 140 | 0 | 2 | 11.4% 6.4% 82.1% | p = 0.013 |

| Water supply 0 Spring 1 Tap 2 Pipe | 116 | 0 | 2 | 21.6% 24.1% 45.7% | |||||

| Water source 0 Superficial 1 Deep source | 140 | 0 | 1 | 21.4% 78.4% | |||||

| Cows 0 No Cows 1 Between 1 to 10 2 >10 cows | 113 | 3 | 0 | 61.1% 26.5% 12.4% | 139 | 1 | 1 | 43.2% 46.4% 10% | p = 0.004 |

| Pigs | 104 | 12 | 0 | 1.66 (2.18) | 132 | 8 | 0 | 2.17 (0.65) | p = 0.093 |

| Garden plot 0 non-active 1 at least one crop | 109 | 7 | 1 | 26.6% 73.4% | 136 | 4 | 1 | 23.5% 76.5% | p = 0.580 |

| Non-labour-reducing electronics | 110 | 6 | 4 | 4.39 (1.41) | 136 | 4 | 4 | 4.67 (0.43) | p = 0.184 |

| Labour-reducing electronics | 110 | 6 | 0 | 1.12 (1.06) | 136 | 4 | 0 | 1.29 (1.86) | p = 0.230 |

| Age pension 0 No pension 1 At least one | 116 | 0 | 0 | 90.5% 9.5% | 140 | 0 | 0 | 68.6% 31.4% | p < 0.001 |

| Residents | 112 | 4 | 5 | 7.37 (2.79) | 139 | 1 | 6 | 7.48 (0.47) | p = 0.742 |

| Year of birth | 114 | 2 | 1984 | 1975.61 (12.44) | 138 | 2 | 1990 | 1976.14 (15.07) | p = 0.759 |

| Birth Region 0, 0 to 250 m 1, 251–500 m 2, 501 m and more | 105 | 35 | 0 | 69.5% 16.2% 14.3% | |||||

| Ossu Components | Natarbora Components | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Tech and Sanitation | 2 Contraception | 3 Traditional | 4 High Fertility | 1 Tech and Sanitation | 2 Traditional | 3 Contraception | 4 High Fertility | |

| Health Ratio | 0.104 | −0.207 | 0.652 | −0.059 | ||||

| Age at first birth | −0.171 | −0.266 | −0.444 | 0.289 | ||||

| Births | −0.068 | 0.041 | 0.132 | 0.854 | −0.086 | −0.044 | 0.117 | 0.807 |

| Child deaths | −0.169 | −0.153 | 0.042 | 0.702 | 0.095 | 0.033 | −0.134 | 0.815 |

| Family planning | 0.250 | 0.685 | −0.185 | 0.150 | −0.068 | 0.06 | 0.741 | 0.059 |

| Education | 0.351 | 0.194 | −0.464 | −0.085 | 0.437 | −0.334 | −0.062 | 0.217 |

| Income | −0.016 | 0.154 | −0.053 | 0.538 | 0.101 | −0.067 | 0.415 | 0.268 |

| Bolsa da mae | −0.080 | 0.709 | −0.169 | 0.059 | −0.276 | −0.17 | 0.508 | −0.11 |

| Sanitation | 0.625 | −0.368 | −0.059 | −0.133 | 0.510 | −0.134 | −0.164 | −0.074 |

| Water source | 0.518 | −0.107 | −0.005 | −0.08 | ||||

| Water supply | −0.197 | 0.524 | 0.285 | −0.213 | ||||

| Cows | 0.378 | 0.100 | 0.650 | 0.166 | 0.033 | 0.783 | 0.11 | 0.06 |

| Pigs | 0.119 | 0.599 | 0.445 | 0.024 | ||||

| Garden plot | −0.296 | −0.084 | 0.477 | −0.048 | ||||

| Non-labour reducing electronics | 0.726 | 0.052 | 0.086 | −0.043 | 0.722 | 0.132 | 0.092 | 0.075 |

| Labour-reducing electronics | 0.710 | 0.090 | 0.031 | −0.129 | 0.733 | 0.087 | 0.168 | 0.049 |

| Age pension | −0.177 | 0.625 | −0.246 | 0.006 | ||||

| Residents | 0.165 | 0.046 | 0.771 | −0.002 | −0.002 | 0.709 | −0.134 | −0.086 |

| Year of birth | 0.165 | 0.108 | 0.138 | −0.686 | 0.071 | −0.117 | 0.179 | −0.556 |

| Birth region | −0.154 | −0.057 | 0.08 | 0.337 | ||||

| % Variance | 13.98 | 13.26 | 13.11 | 11.83 | 13.06 | 12.18 | 11.95 | 10.45 |

| (Rotated eigenvalue) | 1.957 | 1.857 | 1.836 | 1.657 | 1.958 | 1.827 | 1.792 | 1.568 |

| % Total variance | 52.19 | 47.64 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Borquez-Arce, P.; Sumich, C.E.; da Costa, R.; Guizzo-Dri, G.; Spencer, P.R.; Sanders, K.; Judge, D.S. Women’s Life Trajectories in Rural Timor-Leste: A Life History and Life Course Perspective on Reproduction and Empowerment. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14040203

Borquez-Arce P, Sumich CE, da Costa R, Guizzo-Dri G, Spencer PR, Sanders K, Judge DS. Women’s Life Trajectories in Rural Timor-Leste: A Life History and Life Course Perspective on Reproduction and Empowerment. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(4):203. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14040203

Chicago/Turabian StyleBorquez-Arce, Paola, Chiara E. Sumich, Raimundo da Costa, Gabriela Guizzo-Dri, Phoebe R. Spencer, Katherine Sanders, and Debra S. Judge. 2025. "Women’s Life Trajectories in Rural Timor-Leste: A Life History and Life Course Perspective on Reproduction and Empowerment" Social Sciences 14, no. 4: 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14040203

APA StyleBorquez-Arce, P., Sumich, C. E., da Costa, R., Guizzo-Dri, G., Spencer, P. R., Sanders, K., & Judge, D. S. (2025). Women’s Life Trajectories in Rural Timor-Leste: A Life History and Life Course Perspective on Reproduction and Empowerment. Social Sciences, 14(4), 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14040203