Reconfiguration of Informal Social Protection Systems of Older Adults in Sub-Saharan Africa Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Capacity of ISP Systems to Respond to Covariate Shocks

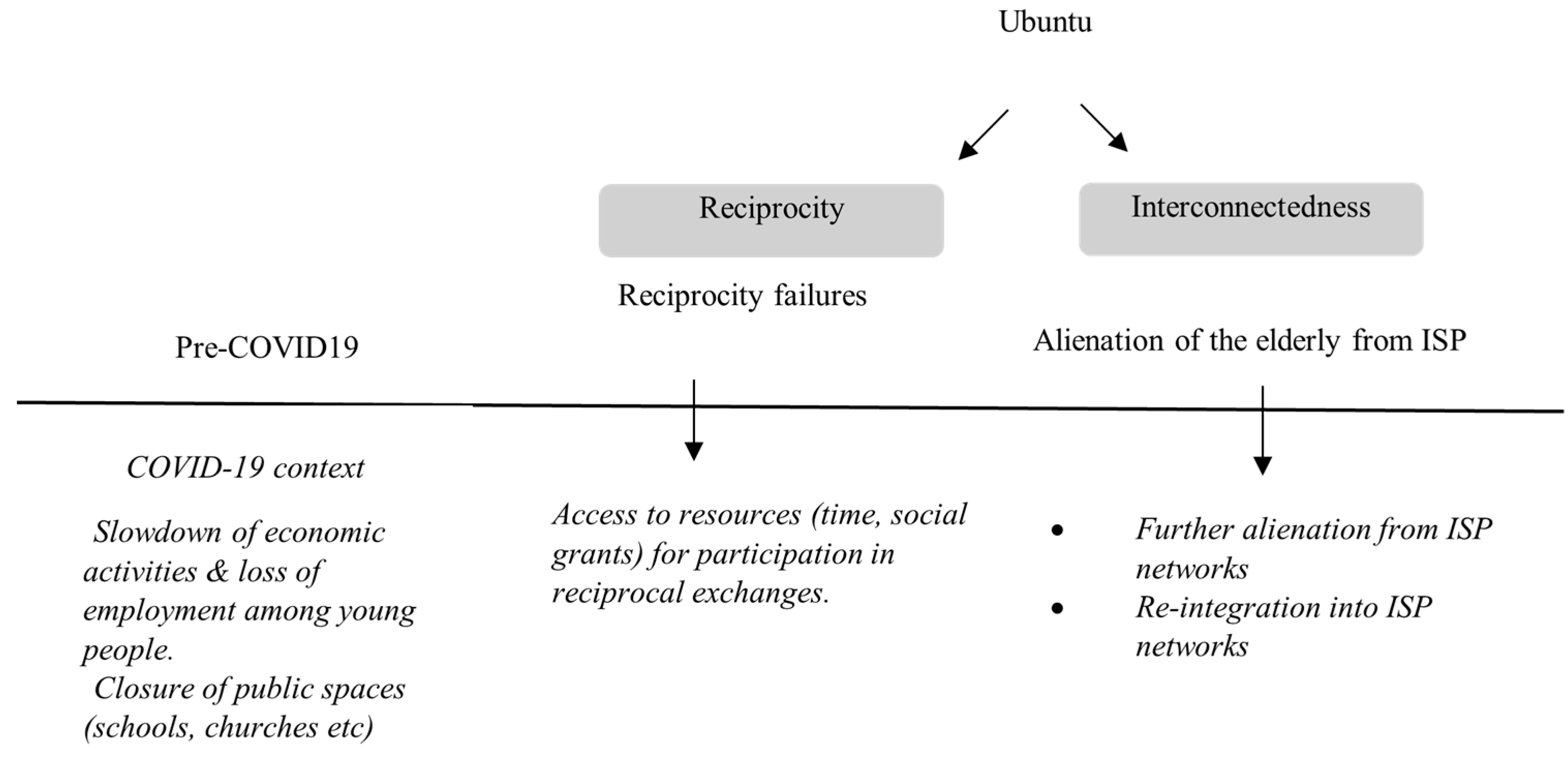

3. Ubuntu—An African Ethic That Undergirds ISP Systems

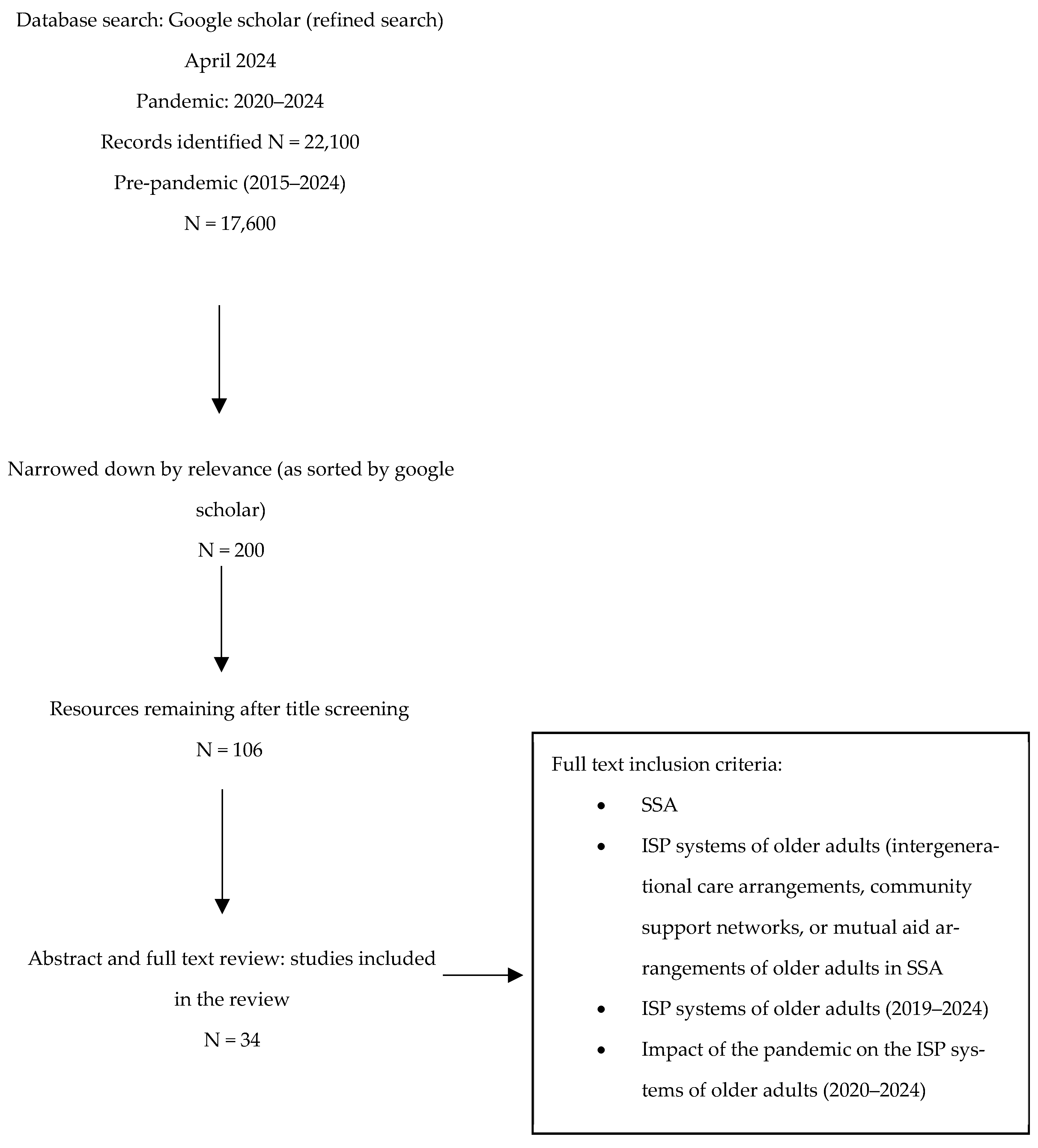

4. Materials and Methods

5. Results

5.1. Features of the ISP Systems of Older Adults Pre-Pandemic

5.1.1. Reciprocity

5.1.2. Reciprocity Failures

5.1.3. Alienation from ISP Networks

5.2. Shifts in ISP Systems Amid the Pandemic

5.2.1. Access to Resources for Participation in Reciprocal Exchanges

5.2.2. Further Alienation from Social Networks

5.2.3. Re-Integration into Social Networks

6. Discussion

7. Strengths and Limitations

8. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adedeji, Isaac Akinkunmi, Andrew Wister, and John Pickering. 2023. COVID-19 experiences of social isolation and loneliness among older adults in Africa: A scoping review. In Frontiers in Public Health. Lausanne: Frontiers Media S.A., vol. 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adesina, Jimi O. 2011. Beyond the social protection paradigm: Social policy in Africa’s development. Canadian Journal of Development Studies/Revue Canadienne d’études Du Développement 32: 454–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinrolie, Olayinka, Augustine C. Okoh, and Michael E. Kalu. 2020. Intergenerational Support between Older Adults and Adult Children in Nigeria: The Role of Reciprocity. Journal of Gerontological Social Work 63: 478–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arthur-Holmes, Francis, and Razak M. Gyasi. 2021. COVID-19 crisis and increased risks of elder abuse in caregiving spaces. Global Public Health 16: 1675–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asante, Emmanuel Akwasi, Kofi Awuviry-Newton, and Kwamina Abekah-Carter. 2021. Social Networks in Limbo. The Experiences of Older Adults During COVID-19 in Ghana. Frontiers in Public Health 9: 772933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avers, Dale, Marybeth Brown, Kevin K. Chui, Rita A. Wong, and Michelle Lusardi. 2011. Editor’s message: Use of the term “elderly”. Journal of Geriatric Physical Therapy 34: 153–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awortwe, Victoria, Jennifer Litela Asare, Samuel Logoniga Gariba, Crispin Rakibu Mbamba, and Vera Ansie. 2023. Witchcraft accusations and older adults: Insights from family members on the struggles of well-being. Journal of Religion, Spirituality and Ageing 37: 167–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awortwi, Nicholas. 2018. Social protection is a grassroots reality: Making the case for policy reflections on community-based social protection actors and services in Africa. Development Policy Review 36: O897–O913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattamishra, Ruchira, and Christopher B. Barrett. 2010. Community-based risk management arrangements: A Review. World Development 38: 923–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braimah, Joseph Asumah, and Mark W. Rosenberg. 2021. “They Do Not Care about Us Anymore”: Understanding the Situation of Older People in Ghana. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Brear, Michelle R., Lenore Manderson, Themby Nkovana, and Guy Harling. 2024. Conceptualisations of “good care” within informal caregiving networks for older people in rural South Africa. Social Science and Medicine 344: 116597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Button, Kirsty, and Thobani Ncapai. 2019. Conflict and negotiation in intergenerational care: Older women’s experiences of caring with the Old Age Grant in South Africa. Critical Social Policy 39: 560–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, Rebecca, Tom Tanhchareun, and J. M. Crescent. 2014. Informal Social Protection: Social Relations and Cash Transfers; Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia. Available online: https://www.dfat.gov.au/sites/default/files/informal-social-protection.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2020).

- Chemen, Sambaladevi, and Youven Naiken Gopalla. 2021. Lived experiences of older adults living in the community during the COVID-19 lockdown—The case of mauritius. Journal of Ageing Studies 57: 100932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Ya-Mei, and Bobbie Berkowitz. 2012. Older adults home- and community-based care service use and residential transitions: A longitudinal study. BMC Geriatrics 12: 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coe, Cati. 2016. Orchestrating Care in Time: Ghanaian Migrant Women, Family, and Reciprocity. American Anthropologist 118: 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curreri, Nereide Alhena, Louise McCabe, Jane Robertson, Isabella Aboderin, Anne Margriet Pot, and Norah Keating. 2023. Family beliefs about care for older people in Central, East, Southern and West Africa and Latin America. International Journal of Care and Caring 7: 343–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dafuleya, Gift. 2018. (Non)state and (in)formal social protection in Africa: Focusing on burial societies. International Social Work 61: 156–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, Ah. 2008. Mind the gap: Suggestions for bridging the divide between formal and informal social security. Law, Democracy & Development 12: 117–132. [Google Scholar]

- Deshingkar, Priya. 2019. The making and unmaking of precarious, ideal subjects—Migration brokerage in the Global South. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45: 2638–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devereux, Stephen. 2021. Social protection responses to COVID-19 in Africa. Global Social Policy 21: 421–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovie, Delali Adjoa. 2021. Pearls in the COVID-19 pandemic: The case of older adults’ lived experiences in Ghana. Interações: Sociedade e as Novas Modernidades 40: 29–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubbeld, Bernard. 2013. How social security becomes social insecurity: Unsettled households, crisis talk and the value of grants in a KwaZulu-Natal village. Acta Juridica 2013: 197–217. [Google Scholar]

- Dubbeld, Bernard. 2021. Granting the future? The temporality of cash transfers in the South African countryside. Revista de Antropologia 64: e186648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Toit, Andries, and David Neves. 2009. Trading on a Grant: Intergrating Formal and Informal Social Protection in Post-Apartheid Migrant Networks. In Brooks World Poverty Institute (BWPI) Working Paper. Cape Town: Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies, University of the Western Cape, BWPI Working Paper 75. [Google Scholar]

- Ebimgbo, Samuel O., Chiemezie S. Atama, Emeka E. Igboeli, Christy N. Obi-Keguna, and Casmir O. Odo. 2022. Community versus family support in caregiving of older adults: Implications for social work practitioners in South-East Nigeria. Community, Work and Family 25: 152–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekoh, Prince Chiagozie, Elizabeth Onyedikachi George, Patricia Uju Agbawodikeizu, Chigozie Donatus Ezulike, Uzoma Odera Okoye, and Ikechukwu Nnebe. 2022. “Further Distance and Silence among Kin”: Social Impact of COVID-19 on Older People in Rural Southeastern Nigeria. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships 20: 347–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekoh, Prince Chiagozie, Patricia Ujunwa Agbawodikeizu, Chukwuemeka Ejimkararonye, Elizabeth Onyedikachi George, Chigozie Donatus Ezulike, and Ikechukwu Nnebe. 2020. COVID-19 in Rural Nigeria: Diminishing Social Support for Older People in Nigeria. Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine 6: 2333721420986301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enworo, Oko Chima. 2023. Beyond Periphery: Dynamics of Indigenous Social Protection Systems in Dealing with Covariate Shocks in Southeastern Nigeria. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, May. [Google Scholar]

- Ewuoso, Cornelius, and Susan Hall. 2019. Core aspects of ubuntu: A systematic review. In South African Journal of Bioethics and Law. Pretoria: South African Medical Association, vol. 12, pp. 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeh, Alex C., Gloria Chepngeno, Abdhalah Ziraba Kasiira, and Zewdu Woubalem. 2006. The Situation of Older People in Poor Urban Settings: The Case of Nairobi, Kenya. In Ageing in Sub-Saharan Africa: Recommendation for Furthering Research. Edited by Barney Cohen and Jane Menken. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fafchamps, Marcel, and Eliana La Ferrara. 2012. Self-Help Groups and Mutual Assistance: Evidence from Urban Kenya. Economic Development and Cultural Change 60: 707–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Femia, Elia E., Steven H. Zarit, Clancy Blair, Shannon E. Jarrott, and Kelly Bruno. 2008. Intergenerational preschool experiences and the young child: Potential benefits to development. Early Childhood Research Quarterly 23: 272–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, James. 2015. Give a Man a Fish: Reflection on the New Politics of Distribution, 1st ed. Durham: Duke University Press, vol. 148. [Google Scholar]

- Gade, Christian B. N. 2012. What is ubuntu? Different interpretations among south africans of african descent. South African Journal of Philosophy 31: 484–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, Alejandro Bonilla, and Jean-Victor Gruat. 2003. Social Protection a Life Cycle Continuum Investment for Social Justice, Poverty Reduction and Sustainable Development. Geneva: International Labour Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Granlund, Stefan, and Tessa Hochfeld. 2020. ‘That Child Support Grant Gives Me Powers’—Exploring Social and Relational Aspects of Cash Transfers in South Africa in Times of Livelihood Change. The Journal of Development Studies 56: 1230–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyasi, Razak M. 2020. COVID-19 and mental health of older Africans: An urgency for public health policy and response strategy. International Psychogeriatrics 32: 1187–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajak, Vivien L., Srishti Sardana, Helen Verdeli, and Simone Grimm. 2021. A Systematic Review of Factors Affecting Mental Health and Well-Being of Asylum Seekers and Refugees in Germany. Frontiers in Psychiatry 12: 643704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Wan, Isabella Aboderin, and Dzifa Adjaye-Gbewonyo. 2020. Africa Ageing: 2020 International Population Reports; Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office.

- International Labour Organization. 2022. World Social Protection Report 2020–22 Regional Companion Report for Africa. Geneva: International Labour Organisation. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/publns (accessed on 28 February 2024).

- Kamiya, Yumiko, and Sara Hertog. 2020. Measuring Household and Living Arrangements of Older Persons Around the World: The United Nations Database on the Households and Living Arrangements of Older Persons 2019. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/content/measuring-household-and-living-arrangements-older-persons-around-world-united-nations (accessed on 28 February 2024).

- Kelly, Gabrielle. 2019. Disability, cash transfers and family practices in South Africa. Critical Social Policy 39: 541–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Ferrara, Eliana. 2002. Self-help Groups and Income Generation in the Informal Settlements of Nairobi. Journal of African Economics 11: 61–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyaapelo, Thabang, Anita Edwards, Nondumiso Mpanza, Samukelisiwe Nxumalo, Zama Nxumalo, Ntombizonke Gumede, Nothando Ngwenya, and Janet Seeley. 2022. COVID-19 and older people’s wellbeing in northern KwaZulu-Natal—The importance of relationships. Wellcome Open Research 7: 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matolino, Bernard, and Wenceslaus Kwindingwi. 2013. The end of ubuntu. South African Journal of Philosophy 32: 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maviza, Gracsious, and Divane Nzima. 2022. Intergenerational Kinship Networks of Support Within Transnational Families in the era of COVID-19 in the South Africa–Zimbabwe Migration Corridor. South African Review of Sociology 52: 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mefteh, Kidus Yenealem, and Bereket Kebede Shenkute. 2022. Experience of Rural Family Caregivers for Older Adults in Co-Residential Family Care Arrangements in Central Ethiopia: Motives of Family Caregivers in Reciprocal Relationship. Patient Preference and Adherence 16: 2473–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merla, Laura, Majella Kilkey, and Loretta Baldassar. 2020a. Examining transnational care circulation trajectories within immobilizing regimes of migration: Implications for proximate care. Journal of Family Research 32: 514–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merla, Laura, Majella Kilkey, and Loretta Baldassar. 2020b. Introduction to the Special Issue “Transnational care: Families confronting borders”. Journal of Family Research 32: 393–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metz, Thaddeus. 2007. Toward an African moral theory. Journal of Political Philosophy 15: 321–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mligo, Elia Shabani. 2022. African principle of reciprocity. Stellenbosch Theological Journal 7: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobasseri, Khorshid, Hossein Matlabi, Hamid Allahverdipour, Fariba Pashazadeh, and Ahmad Kousha. 2023. Structure and Organization of Home-Based Care for Older Adults in Different Countries: A Scoping Review. Health Scope 12: e136546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murayama, Yoh, Hiroshi Murayama, Masami Hasebe, Jun Yamaguchi, and Yoshinori Fujiwara. 2019. The impact of intergenerational programs on social capital in Japan: A randomized population-based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 19: 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niño-Zarazúa, Miguel, Armando Barrientos, Samuel Hickey, and David Hulme. 2012. Social Protection in Sub-Saharan Africa: Getting the Politics Right. World Development 40: 163–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oduro, Abena D. 2010. Formal and Informal Social Protection in Sub-Saharan Africa [Paper Presentation]. Promoting Resilience Through Social Protection in Sub-Saharan Africa Workshop 2010: European Report on Development, Dakar, Senegal. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/4665876/Formal_and_Informal_Social_Protection_in_Africa (accessed on 3 February 2020).

- Onzaberigu, Nachinaab John, Kwadwo Ofori-Dua, Peter Dwumah, and Esmeranda Manful. 2024. Elderly Victimization in the Context of Witchcraft Accusations and Persons Accused of Witchcraft Practices Living Within the Gambaga Witches’ Camp: Understanding of Human Rights. Journal of Victimology and Victim Justice 7: 145–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouma, Caleb, Joy Obando, and Micheal Koech. 2012. Post Drought recovery strategies among the Turkana pastoralists in Northern Kenya. Scholarly Journals of Biotechnology 1: 90–100. [Google Scholar]

- Oware, Phoene Mesa. 2023. The Potential for Complementarity Between Formal and Informal Social Protection Programmes in Kenya: A Case Study. Cape Town: University of the Western Cape. [Google Scholar]

- Sadruddin, Aalyia Feroz Ali. 2020. The Care of “Small Things”: Ageing and Dignity in Rwanda. Medical Anthropology: Cross Cultural Studies in Health and Illness 39: 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuels, Fiona, and Maria Stavropoulou. 2016. ‘Being Able to Breathe Again’: The Effects of Cash Transfer Programmes on Psychosocial Wellbeing. Journal of Development Studies 52: 1099–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segona, E., Erin Torkelson, and Wanga Zembe-Mkabile. 2021. Social Protection in a Time of COVID: Lessons for Basic Income Support. Durham: Durham University. Available online: https://www.blacksash.org.za (accessed on 26 February 2024).

- Small, Jeon, Carolyn Aldwin, Paul Kowal, and Somnath Chatterji. 2019. Ageing and HIV-Related Caregiving in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Social Ecological Approach. The Gerontologist 59: e223–e240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhera, Javeed. 2022. Narrative Reviews: Flexible, Rigorous, and Practical. Journal of Graduate Medical Education 14: 414–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, Anh, Sarina Kidd, and Katherine Dean. 2019. ‘I Feel More Loved’: Autonomy, Self-Worth and Kenya’s Universal Pension. Sidcup: Development Pathways. Available online: https://www.developmentpathways.co.uk/publications/i-feel-more-loved-autonomy-self-worth-and-kenyas-universal-pension/ (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- United Nations University Centre for Policy Research. 2023. Migration and Decent Work: Challenges for the Global South A Synthesis of Ideas and Solutions Presented at a UNU-CPR Migration Policy Roundtable. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5096003 (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Walcott, Rebecca, Carly Schmidt, Marina Kaminsky, Roopal Jyoti Singh, Leigh Anderson, Sapna Desai, and Thomas de Hoop. 2023. Women’s groups, covariate shocks, and resilience: An evidence synthesis of past shocks to inform a response to COVID-19. Gates Open Research 7: 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization [WHO]. 2017. WHO Series on Long Term Care: Towards Long-Term Care Systems in Sub-Saharan Africa. Edited by Anne Margriet Pot and John Beard. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789241513388 (accessed on 4 September 2020).

- Zelalem, Abraham, Messay Gebremariam Kotecho, and Margaret E. Adamek. 2021. “The Ugly Face of Old Age”: Elders’ Unmet Expectations for Care and Support in Rural Ethiopia. The International Journal of Ageing and Human Development 92: 215–39. [Google Scholar]

- Zembe-Mkabile, Wanga, Rebecca Surender, David Sanders, Rina Swart, Vundli Ramokolo, Gemma Wright, and Tanya Doherty. 2018. “To be a woman is to make a plan”: A qualitative study exploring mothers’ experiences of the Child Support Grant in supporting children’s diets and nutrition in South Africa. BMJ Open 8: e019376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Theme | Features of the ISP Systems of Older Adults Pre-Pandemic | Shifts in the ISP Systems of Older Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic |

|---|---|---|

| Sub-theme |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oware, P.M.; Zembe, Y.; Zembe-Mkabile, W. Reconfiguration of Informal Social Protection Systems of Older Adults in Sub-Saharan Africa Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Narrative Review. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14040200

Oware PM, Zembe Y, Zembe-Mkabile W. Reconfiguration of Informal Social Protection Systems of Older Adults in Sub-Saharan Africa Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Narrative Review. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(4):200. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14040200

Chicago/Turabian StyleOware, Phoene Mesa, Yanga Zembe, and Wanga Zembe-Mkabile. 2025. "Reconfiguration of Informal Social Protection Systems of Older Adults in Sub-Saharan Africa Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Narrative Review" Social Sciences 14, no. 4: 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14040200

APA StyleOware, P. M., Zembe, Y., & Zembe-Mkabile, W. (2025). Reconfiguration of Informal Social Protection Systems of Older Adults in Sub-Saharan Africa Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Narrative Review. Social Sciences, 14(4), 200. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14040200