Psychosocial Differences Between Female and Male Students in Learning Patterns and Mental Health-Related Indicators in STEM vs. Non-STEM Fields

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Male-Female Differences in Learning Dimensions: Theoretical Framework

1.2. Male-Female Differences in Mental Health in Education

1.3. Gender and STEM

1.4. Parenting Dimensions Affecting Male-Female Differences in Learning

1.5. Addressing the Needs for Research in Male-Female Differences in STEM Fields Based on the Diversity in Learning Patterns

- Coping with Difficulties: Managing mental health distresses and psychosocial difficulties related to learning, such as anxiety, apathy, demotivation, bad mood, irritability, lack of attention, low achievement expectations, and difficulties dealing with the social learning environments.

- Effort: Reflecting perseverance, regularity, capacity to delay reward, and internal attribution of performance.

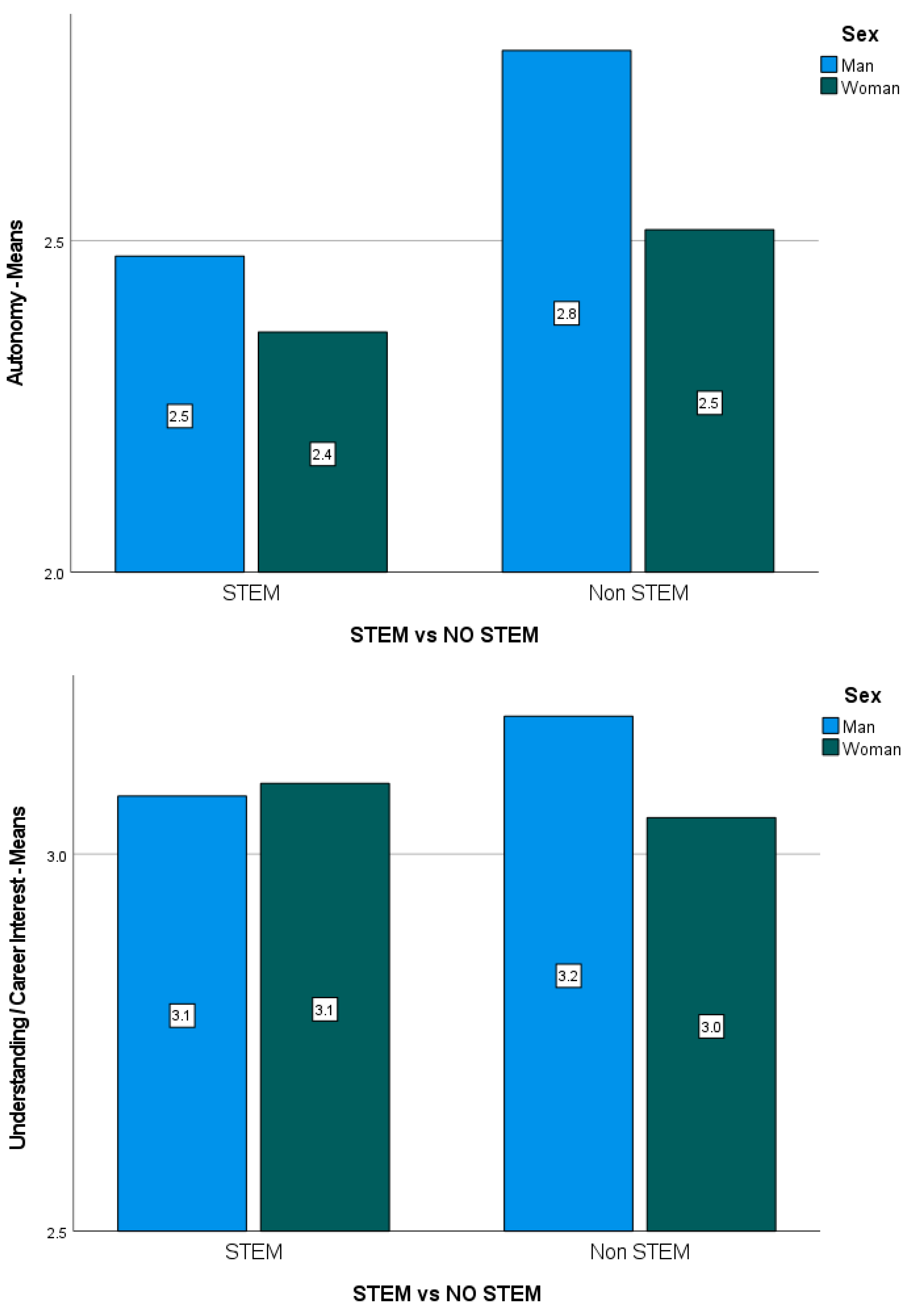

- Autonomy: Embracing active learning, integrating information from various sources, developing personal theories, and seeking evidence.

- Learning by Understanding and Career Interest: Demonstrating intrinsic motivation to deeply understand the discipline for professional preparation.

- Social Context: Preferring studying alone or in groups and choosing the study environment (home vs. university).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Instrument

2.3. Design and Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptives and Correlations

3.2. Male-Female Differences in Learning Dimensions: Study Findings

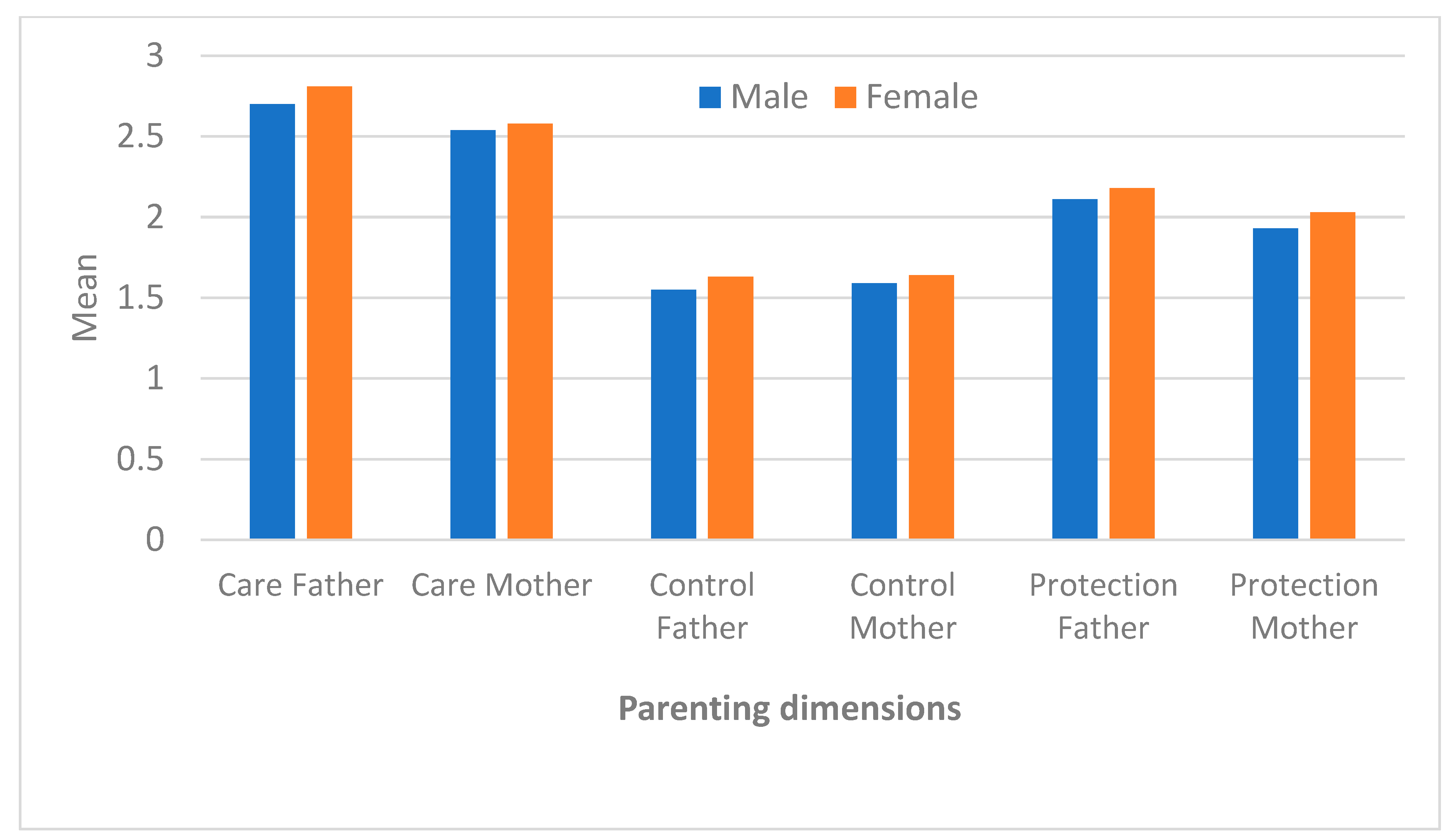

3.3. Differences in Paternal and Maternal Parenting Practices Related to Learning Dimensions

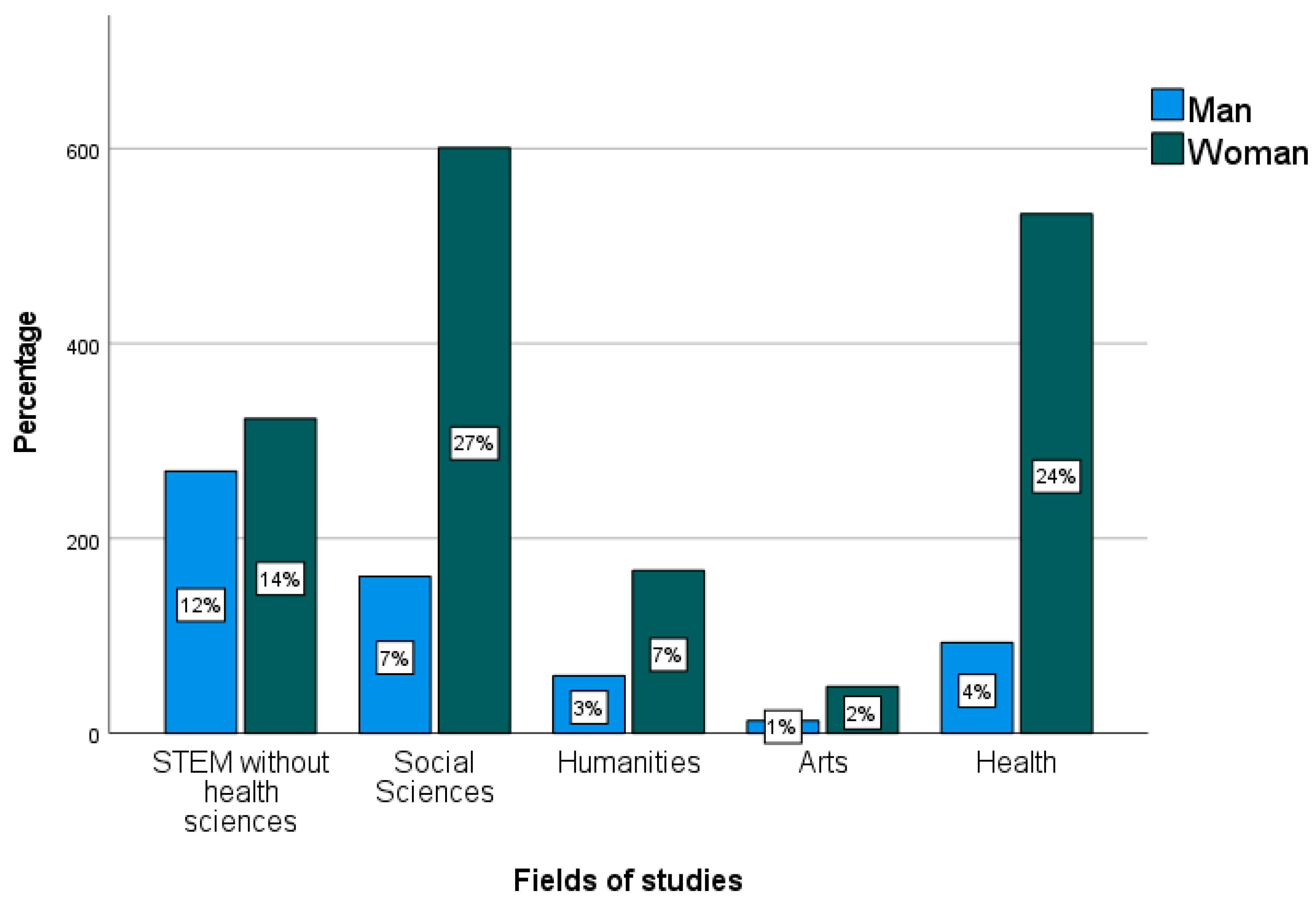

3.4. Sex Differences in Learning Dimensions in STEM Fields

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Female university students expressed greater psychosocial difficulties, poorer perceived self-efficacy, and less autonomy in their studies than male students, but with no differences in academic performance.

- Mothers’ and fathers’ roles continue to influence their sons’ and daughters’ learning and mental health patterns in higher education according to the traditional gender roles. The mother’s role continues to have a stronger and more significant impact than the father’s role.

- Female students in STEM fields seem to be more similar to male students in their learning patterns and mental health than students in non-STEM fields.

- In the present study, traditional gender roles and attitudes seem to feature among university students and in the impact of their father’s and mother’s roles. Although we have made significant progress in equality between females and males in terms of presence and achievement in higher education, there is considerable room for psychological, psychosocial, and psychoeducational progress before we can reach a truly egalitarian education system.

- If we are to improve the presence of females in STEM fields, we need to make greater efforts to reduce gender attributions from the early stages of education.

- We need to apply more in-depth psychosocial and psychoeducational work on eliminating gender stereotypes—which will otherwise persist across generations—in order to achieve truly inclusive education for males and females.

- Educational policies need to foster environments that encourage autonomy and emotional resilience, especially in fields where females are underrepresented. In addition, it is crucial to promote more inclusive and stereotype-free education from the earliest stages in order to reduce gender gaps in access and success in STEM and non-STEM fields.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Questionnaire Used in the Study

| Dimension | Item | |

|---|---|---|

| Coping with difficulties | 15 | The circumstances determine the final results of my studies (learning, grades), whether they are good or bad. |

| 20 | Bad mood/Irritability. | |

| 21 | Anxiety/nervousness. | |

| 22 | Apathy/Discouragement/Reluctance. | |

| 23 | Difficulties in attention and concentration. | |

| 25 | Poor expectations of academic achievement or success. | |

| 26 | Low interest of classmates in learning. | |

| 27 | The university lacks resources for the students. | |

| 28 | Difficulties at home in concentrating on studying (home environment, room to study, etc.). | |

| Effort | 1 | I study with perseverance and regularity. |

| 3 | I study and concentrate hardest under the pressure of an upcoming exam. | |

| 9 | I am able to manage my time and study environment. | |

| 10 | I am able to delay the satisfaction of desires or impulses. | |

| 12 | Frequent daily reading (including all sorts of texts). | |

| 24 | Poor consistency in my study habits. | |

| Autonomy | 4 | I like to develop my own theories and I pay attention to whether there are real examples to support or refute my theories. |

| 5 | I search for useful and practical applications of new knowledge. | |

| 8 | I read complementary texts and watch videos that are not required for the exams, for my own knowledge. | |

| 13 | I organise and integrate information gathered from different sources in my learning. | |

| 14 | I search for evidence of my theories. | |

| Understanding/Career Interest | 6 | When I study, I focus on understanding the concepts more than anything else. |

| 7 | I memorize the concepts and theories without needing to understand everything perfectly. | |

| 11 | When studying, I focus primarily on relating ideas and concepts. | |

| 18 | The main focus of my studies is professional development for my career. | |

| 19 | I know all the profiles and professional prospects of my course with a view to my future career. | |

| Social Context | 2 | I believe that studying in a group helps me to solve questions that I cannot solve by myself. |

| 16 | I study in in spaces provided at the university. | |

| 17 | I study at home. |

- Parental Care:

- −

- I think that my parents tried to make my adolescence stimulating, interesting and instructive (for instance by giving me good books, arranging for me to go to holiday camps, taking me to clubs).

- −

- When faced with a difficult task. I felt supported by my parents.

- Parental Control:My parents would punish me strictly, even for trifles (small offenses).

- Parental Protection:

- Male.

- Female.

- I prefer not to answer

- F (grade below 5)

- E-D-C (grades between 5–6)

- B (grades between 7–8)

- A (grades between 9–10)

References

- Affrunti, Nicholas W., and Golda S. Ginsburg. 2012. Maternal overcontrol and child anxiety: The mediating role of perceived competence. Child Psychiatry and Human Development 43: 102–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbaria, Qutaiba, and Fayez Mahamid. 2023. The association between parenting styles, maternal self-efficacy, and social and emotional adjustment among Arab preschool children. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica 36: 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguado, Mercedes López. 2011. Estrategias de aprendizaje en estudiantes universitarios: Diferencias por género, curso y tipo de titulación. Education in the Knowledge Society 12: 203–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldosari, Mohammad A., Aljazi H. Aljabaa, Fares S. Al-Sehaibany, and Sahar F. Albarakati. 2018. Learning style preferences of dental students at a single institution in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, evaluated using the VARK questionnaire. Advances in Medical Education and Practice 9: 179–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ALMasaudi, Ahmad Saleem. 2021. The differences between genders in academic perseverance, motivations, and their relation to academic achievement in the University of Tabuk. Psychology and Behavioral Sciences International Journal 9: 131–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, Catalina, Domingo Gallego, and Peter Honey. 1995. Los Estilos de Aprendizaje: Procedimientos de Diagnóstico y Mejora. Bilbao: Mensajero. [Google Scholar]

- Archer, Louise, Jennifer DeWitt, Jonathan Osborne, Justin Dillon, Beatrice Willis, and Billy Wong. 2018. “Not girly, not sexy, not glamorous”: Primary school girls’ and parents’ constructions of science aspirations. In Pedagogical Responses to the Changing Position of Girls and Young Women. Edited by C. Jackson and J. S. Roche. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge, pp. 171–94. [Google Scholar]

- Arredondo Trapero, Florina Guadalupe, José Carlos Vázquez Parra, and Luz María Velázquez Sánchez. 2019. STEM y brecha de género en Latinoamérica. Revista de El Colegio de San Luis. Nueva época 9: 137–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrindell, Willem A., Alma Akkerman, Nuri Bagés, Lya Feldman, Vicente E. Caballo, Tian P. S. Oei, Barbara Torres, Gloria Canalda, Josefina Castro, Iain M. Montgomery, and et al. 2005. The short-EMBU in Australia, Spain, and Venezuela. European Journal of Psychological Assessment 21: 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrindell, Willem A., Hjördis Perris, Mercedes Denia, Jan Van Der Ende, Carlo Perris, Anna Kokkevi, José Ignacio Anasagasti, and Martin Eisemann. 1988. The constancy of structure of perceived parental rearing style in Greek and Spanish subjects as compared with the Dutch. International Journal of Psychology 23: 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, Joaquín, José Manuel Aguilar, and José Javier Lorenzo. 2012. La ansiedad ante los exámenes en estudiantes universitarios: Relaciones con variables personales y académicas. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology 10: 333–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baader, Tomas, Carmen Rojas, José Luis Molina, Marcelo Gotelli, Catalina Alamo, Carlos Fierro, Silvia Venezian, and Paula Dittus. 2014. Diagnóstico de la prevalencia de trastornos de la salud mental en estudiantes universitarios y los factores de riesgo emocionales asociados. Revista Chilena de Neuro-Psiquiatría 52: 167–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, Syeda S. 2019. Academic achievement: Interplay of positive parenting, self-esteem, and academic procrastination. Australian Journal of Psychology 72: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, Alessandro. 2020. Las Mujeres en Ciencias, Tecnología, Ingeniería Y Matemáticas en América Latina y el Caribe. New York City: ONU Mujeres. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán, Jesús. 1993. Procesos, Estrategias y Técnicas de Aprendizaje. Santa Cruz: Síntesis. [Google Scholar]

- Berlin, M., B. Modin, P. A. Gustafsson, A. Hjern, and M. Bergström. 2012. The Impact of School on Children’s and Adolescents’ Mental Health. Stockholm: The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare and Center for Health Equity Studies (CHESS). [Google Scholar]

- Blackmore, Conner, Julian Vitali, Louise Ainscough, Tracey Langfield, and Kay Colthorpe. 2021. A review of self-regulated learning and self-efficacy: The key to tertiary transition in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). International Journal of Higher Education 10: 169–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boson, Karin, Peter Wennberg, Claudia Fahlke, and Kristina Berglund. 2019. Personality traits as predictors of early alcohol inebriation among young adolescents: Mediating effects by mental health and gender-specific patterns. Addictive Behaviors 95: 152–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brackett, Marc A., Susan E. Rivers, Sara Shiffman, Nicole Lerner, and Peter Salovey. 2006. Relating emotional abilities to social functioning: A comparison of self-report and performance measures of emotional intelligence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 91: 780–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bully, Paola, Joana Jaureguizar, Elena Bernaras, and Iratxe Redondo. 2019. Relationship between parental socialization, emotional symptoms, and academic performance during adolescence: The influence of parents’ and teenagers’ gender. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16: 2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, Carmen Cecilia, Raymundo Abello, and Jorge Palacios. 2007. Relación del burnout y el rendimiento académico con la satisfacción frente a los estudios en estudiantes universitarios. Avances en Psicología Latinoamericana 25: 98–111. [Google Scholar]

- Caballo, Vicente E., Isabel C. Salazar, Benito Arias, María Jesús Irurtia, and Marta Calderero. 2010. Validación del “Cuestionario de ansiedad social para adultos” (CASO-A30) en universitarios españoles: Similitudes y diferencias entre carreras universitarias y comunidades autónomas. Behavioral Psychology 18: 5–34. [Google Scholar]

- Camarero Suárez, Francisco José, Francisco de Asís Martín del Buey, and Francisco Javier Herrero Díez. 2000. Estilos y estrategias de aprendizaje en estudiantes universitarios. Psicothema 12: 615–22. [Google Scholar]

- Carreño, María Jacqueline Sepúlveda, Mariela López Quiero, Pablo Torres Vergara, and Javiana Luengo Contreras. 2011. Diferencias de género en el rendimiento académico y en el perfil de estilos y de estrategias de aprendizaje en estudiantes de química y farmacia de la Universidad de Concepción. Revista Estilos de Aprendizaje 7: 135–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casad, Bettina J., Patricia Hale, and Faye L. Wachs. 2017. Stereotype threat among girls: Differences by gender identity and math education context. Psychology of Women Quarterly 41: 513–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo Riquelme, Víctor, Nicolás Cabezas Maureira, Constanza Vera Navarro, and Constanza Toledo Puente. 2021. Ansiedad al aprendizaje en línea: Relación con actitud, género, entorno y salud mental en universitarios. Revista Digital de Investigación en Docencia Universitaria 15: e1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaplin, Tara M., and Amelia Aldao. 2013. Gender differences in emotion expression in children: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin 139: 735–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheema, Jehanzeb R., and Anastasia Kitsantas. 2014. Influences of disciplinary classroom climate on high school student self-efficacy and mathematics achievement: A look at gender and racial–ethnic differences. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education 12: 1261–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Wen, and Chia-Chun Wu. 2021. Family socioeconomic status and children’s gender differences in Taiwanese teenagers’ perception of parental rearing behaviors. Journal of Child and Family Studies 30: 1619–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheryan, Sapna, Sianna A. Ziegler, Amanda K. Montoya, and Lily Jiang. 2017. Why are some STEM fields more gender balanced than others? Psychological Bulletin 143: 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, David M. 1986. A cognitive approach to panic. Behaviour Research and Therapy 24: 461–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colorado, Yuly Suárez, and Carlos Wilches Bisval. 2015. Habilidades emocionales en una muestra de estudiantes universitarios: Las diferencias de género. Educación y Humanismo 17: 119–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cordero, Andrea Estefanía Rossi, and Mario Barajas Frutos. 2015. Elección de estudios CTIM y desequilibrios de género. Enseñanza de las Ciencias 33: 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvencek, Dario, Ružica Brečić, Dora Gacesa, and Andrew N. Meltzoff. 2021. Development of math attitudes and math self-concepts: Gender differences, implicit-explicit dissociations, and relations to math achievement. Child Development 92: e940–e956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Buey, Francisco Martín, and Francisco Camarero Suárez. 2001. Diferencias de género en los procesos de aprendizaje universitarios. Psicothema 13: 598–604. [Google Scholar]

- Dell’Osso, Liliana, Marianna Abelli, Stefano Pini, Barbara Carpita, Marina Carlini, Francesco Mengali, Rosalba Tognetti, Francesco Rivetti, and Gabriele Massimetti. 2015. The influence of gender on social anxiety spectrum symptoms in a sample of university students. Rivista di Psichiatria 50: 295–301. [Google Scholar]

- Desy, Elizabeth A., Scott A. Peterson, and Vicky Brockman. 2011. Gender differences in science-related attitudes and interests among middle school and high school students. Science Educator 20: 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Domes, Gregor, Alexander Lischke, Christoph Berger, Annette Grossmann, Karlheinz Hauenstein, Markus Heinrichs, and Sabine C. Herpertz. 2010. Effects of intranasal oxytocin on emotional face processing in women. Psychoneuroendocrinology 35: 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doná, Stella Maris, María Susana Lopetegui, Lilia Elba Rossi Casé, and Rosa Haydée Neer. 2010. Estrategias de aprendizaje y rendimiento académico según el género en estudiantes universitarios. Revista de Psicología 11: 199–211. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte, Oswaldo Soria. 2019. Contexto familiar y los factores intervinientes en el rendimiento académico del sujeto educativo: Aproximación diagnóstica. Polo del Conocimiento 4: 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, Daniel, Justin Hunt, and Nicole Speer. 2013. Mental health in American colleges and universities: Variation across student subgroups and across campuses. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 201: 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Entwistle, Noel, Maureen Hanley, and Dai Hounsell. 1979. Identifying distinctive approaches to studying. Higher Education 8: 365–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essau, Cecilia A., Judith Conradt, and Franz Petermann. 2000. Frequency, comorbidity, and psychosocial impairment of anxiety disorders in adolescents. Journal of Anxiety Disorders 14: 263–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernanda-Molina, María, María Julia Raimundi, and Lucía Bugallo. 2017. La percepción de los estilos de crianza y su relación con las autopercepciones de los niños de Buenos Aires: Diferencias en función del género. Universitas Psychologica 16: 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Castillo, A. 2009. Ansiedad durante pruebas de evaluación académica: Influencia de la cantidad de sueño y la agresividad. Salud Mental 32: 479–86. [Google Scholar]

- Fortin, Nicole M., Philip Oreopoulos, and Shelley Phipps. 2015. Leaving boys behind: Gender disparities in high academic achievement. Journal of Human Resources 50: 549–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, Perry C., and Aaron S. Horn. 2017. Mental health issues and counseling services in US higher education: An overview of recent research and recommended practices. Higher Education Policy 30: 263–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuente, J., F. Justicia, I. Arcilla, and A. Soto. 1994. Factores Condicionantes de las Estrategias de Aprendizaje y del Rendimiento Académico en Alumnos Universitarios, a Través del ACRA. Investigación del Dpto. de Psicología Evolutivo y de la Educación. La Cañada de San Urbano: Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de la Educación, Universidad de Almería. [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes, María C., Antonio Alarcón, Enrique Gracia, and Fernando García. 2015. School adjustment among Spanish adolescents: Influence of parental socialization. Cultura y Educación: Revista de Teoría, Investigación y Práctica 27: 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaibor-González, Ismael, and Rodrigo Moreta-Herrera. 2020. Optimismo disposicional, ansiedad, depresión y estrés en una muestra del Ecuador: Análisis intergénero y de predicción. Actualidades en Psicología 34: 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandarillas, Miguel Ángel. 1995. Culture and Physiology: The Role of Rearing Practices on Physiological Activity: A Multidisciplinary Study. Ph.D. dissertation, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Madrid, Spain. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10486/13160 (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Gandarillas, Miguel Ángel. 2022. An Integrated Approach to Learning Diversity and Its Psychosocial Predictors in the University Context. Preliminary Study. In Teaching Innovation and Educational Practices for Quality Education. Edited by C. Romero. Madrid: Dykinson, pp. 837–63. [Google Scholar]

- Gandarillas, Miguel Ángel, María Natividad Elvira-Zorzo, and M. Rodríguez-Vera. 2024a. The Impact of Parenting Practices and Family Economy on Psychological Wellbeing and Learning Patterns in Higher Education Students. Psicologia Reflexão e Crítica 37: 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandarillas, Miguel Ángel, María Natividad Elvira-Zorzo, Gabriela Alicia Pica-Miranda, and Bernardita Correa-Concha. 2024b. The Impact of Family Factors and Digital Technologies on Mental Health in University Students. Frontiers in Psychology 15: 1433725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Qingsong, and Yongxia Wei. 2023. Understanding the cultivation mechanism for mental health education of college students in campus culture construction from the perspective of deep learning. Current Psychology 43: 1715–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garber, Lawrence L., Eva M. Hyatt, and Ünal Ö. Boya. 2017. Gender differences in learning preferences among participants of serious business games. International Journal of Management Education 15: 11–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, Francisco Cano. 2000. Diferencias de género en estrategias y estilos de aprendizaje. Psicothema 12: 360–67. [Google Scholar]

- García-Holgado, Alicia, Amparo Camacho Díaz, and Francisco J. García-Peñalvo. 2019. La brecha de género en el sector STEM en América Latina: Una propuesta europea. Paper presented at CINAIC: V Congreso Internacional sobre Aprendizaje, Innovación y Competitividad, Madrid, Spain, October 9–11; pp. 704–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnefski, Nadia, Jan Teerds, Vivian Kraaij, Jeroen Legerstee, and Tessa van Den Kommer. 2004. Cognitive emotion regulation strategies and depressive symptoms: Differences between males and females. Personality and Individual Differences 36: 267–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gfellner, Barbara M., and Ana I. Córdoba. 2020. The interface of identity distress and psychological problems in students’ adjustment to university. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology 61: 527–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gili, Margalida, Javier García Campayo, and Miquel Roca. 2014. Crisis económica y salud mental. Informe SESPAS 2014. Gaceta Sanitaria 28: 104–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González Cabanach, Ramón, Francisca Fariña, Carlos Freire Rodríguez, Patricia González Berruga, and María del Mar Ferradás. 2013. Diferencias en el afrontamiento del estrés en estudiantes universitarios hombres y mujeres. European Journal of Education and Psychology 6: 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, Mellissa S., and Ming Cui. 2012. The effect of school-specific parenting processes on academic achievement in adolescence and young adulthood. Family Relations 61: 728–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Ortiz, Olga, Rosario Del Rey, Eva M. Romera, and Rosario Ortega-Ruiz. 2015. Los estilos educativos paternos y maternos en la adolescencia y su relación con la resiliencia, el apego y la implicación en acoso escolar. Anales de Psicología 31: 979–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, B. Sue, Michael E. Hall, Carolyn Dias-Karch, Michael H. Haischer, and Christine Apter. 2021. Gender differences in perceived stress and coping among college students. PLoS ONE 16: e0255634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunderson, Elizabeth A., Gerardo Ramirez, Susan C. Levine, and Sian L. Beilock. 2012. The role of parents and teachers in the development of gender-related math attitudes. Sex Roles 66: 153–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guterman, Oz, and Ari Neuman. 2018. Personality, socio-economic status, and education: Factors that contribute to the degree of structure in homeschooling. Social Psychology of Education 21: 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderlong Corpus, Jennifer, and Mark R. Lepper. 2007. The effects of person versus performance praise on children’s motivation: Gender and age as moderating factors. Educational Psychology 27: 487–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernesniemi, Elina, Hannu Räty, Kati Kasanen, Xuejiao Cheng, Jianzhong Hong, and Matti Kuittinen. 2017. Burnout among Finnish and Chinese university students. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology 58: 400–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, Lucía, Mohamed Al-Lal, and Laila Mohamed. 2020. Academic performance, self-concept, personality, and emotional intelligence in primary education: Analysis by gender and cultural group. Frontiers in Psychology 10: 3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, Lucía, Rafael E. Buitrago, and Sergio Cepero. 2017. Emotional intelligence in Colombian primary school children: Location and gender analysis. Universitas Psychologica 16: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Yongmei, and Jiaying Luo. 2022. Psychometric evaluation of EMBU for junior high school students in Guangdong Province. Psychiatry 5: 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Xiaowen, and Gillian B. Yeo. 2020. Emotional exhaustion and reduced self-efficacy: The mediating role of deep and surface learning strategies. Motivation and Emotion 44: 785–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Chiungjung. 2013. Gender differences in academic self-efficacy: A meta-analysis. European Journal of Psychology of Education 28: 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inzunza Melo, Bárbara Cecilia, Carolina Márquez Urrizola, and Cristhian Pérez Villalobos. 2020. Relación entre aprendizaje autorregulado, antecedentes académicos y características sociodemográficas en estudiantes de medicina. Educación Médica Superior 34: 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Jaureguizar, Joana, Elena Bernaras, Paola Bully, and Maite Garaigordobil. 2018. Perceived parenting and adolescents’ adjustment. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica 31: 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, Megan M., Audrey R. Tyrka, George M. Anderson, Lawrence H. Price, and Linda L. Carpenter. 2008. Sex differences in emotional and physiological responses to the Trier Social Stress Test. Journal of Behavioral Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry 39: 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, Ronald C. 2003. Epidemiology of women and depression. Journal of Affective Disorders 74: 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, Ronald C., Kathleen R. Merikangas, and Philip S. Wang. 2007. Prevalence, comorbidity, and service utilization for mood disorders in the United States at the beginning of the twenty-first century. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 3: 137–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ketchen Lipson, Sarah, S. Michael Gaddis, Justin Heinze, Kathryn Beck, and Daniel Eisenberg. 2015. Variations in student mental health and treatment utilization across U.S. colleges and universities. Journal of American College Health 63: 388–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khodarahimi, Siamak, and Rayhan Fathi. 2016. Mental health, coping styles, and risk-taking behaviors in young adults. Journal of Forensic Psychology Practice 16: 287–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Yeeun, Sog Yee Mok, and Tina Seidel. 2020. Parental influences on immigrant students’ achievement-related motivation and achievement: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review 30: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, David A. 1984. Experiential Learning. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Latas, Milan, Marina Pantić, and Danilo Obradović. 2010. Analysis of test anxiety in medical students. Medicinski Pregled 63: 863–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lattie, Emily G., Elizabeth C. Adkins, Nathan Winquist, Colleen Stiles-Shields, Q. Eileen Wafford, and Andrea K. Graham. 2018. Digital mental health interventions for depression, anxiety, and enhancement of psychological well-being among college students: Systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research 21: e12869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, Jaime, Juan L. Núñez, and Jeffrey Liew. 2015. Self-determination and STEM education: Effects of autonomy, motivation, and self-regulated learning on high school math achievement. Learning and Individual Differences 43: 156–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leppink, Eric W., Brian L. Odlaug, Katherine Lust, Gary Christenson, and Jon E. Grant. 2016. The young and the stressed: Stress, impulse control, and health in college students. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 204: 931–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leupold, Christopher R., Erika C. Lopina, and Julianne Erickson. 2020. Examining the effects of core self-evaluations and perceived organizational support on academic burnout among undergraduate students. Psychological Reports 123: 1260–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lietaert, Sofie, Debora Roorda, Ferre Laevers, Karine Verschueren, and Bieke De Fraine. 2015. The gender gap in student engagement: The role of teachers’ autonomy support, structure, and involvement. British Journal of Educational Psychology 85: 498–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipson, Sarah Ketchen, Emily G. Lattie, and Daniel Eisenberg. 2019. Increased rates of mental health service utilization by U.S. college students: 10-year population-level trends (2007–2017). Psychiatric Services 70: 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez, Luis-Joaquin Garcia, Candido J. Ingles, and Jose M. Garcia-Fernandez. 2008. Exploring the relevance of gender and age differences in the assessment of social fears in adolescence. Social Behavior and Personality 36: 385–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugo, Carlos Saul Juarez, Gabriela Rodriguez Hernandez, and Elba Luna Montijo. 2012. El cuestionario de estilos de aprendizaje CHAEA y la escala de estrategias de aprendizaje ACRA como herramienta potencial para la tutoría académica. Revista de Estilos de Aprendizaje 10: 148–71. [Google Scholar]

- Lund, Emily M., and Scott W. Ross. 2017. Bullying perpetration, victimization, and demographic differences in college students: A review of the literature. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 18: 348–60. [Google Scholar]

- MacCann, Carolyn, Yixin Jiang, Luke E. R. Brown, Kit S. Double, Micaela Bucich, and Amirali Minbashian. 2020. Emotional intelligence predicts academic performance: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin 146: 150–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mammadov, Sakhavat. 2022. Big Five personality traits and academic performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Personality 90: 222–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardia, Kanti V. 1970. Measures of Multivariate Skewness and Kurtosis with Applications. Biometrika 57: 519–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martineli, Ana Karina Braguim, Fernanda Aguiar Pizeta, and Sonia Regina Loureiro. 2018. Behavioral problems of school children: Impact of social vulnerability, chronic adversity, and maternal depression. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica 31: 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez, Isabel M., Isabella Meneghel, and Jonathan Peñalver. 2019. ¿El género afecta en las estrategias de afrontamiento para mejorar el bienestar y el desempeño académico? Revista de Psicodidáctica 24: 111–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masud, Sarwat, Syed Hamza Mufarrih, Nada Qaisar Qureshi, Fahad Khan, Saad Khan, and Muhammad Naseem Khan. 2019. Academic performance in adolescent students: The role of parenting style and socio-demographic factors. A cross-sectional study from Peshawar, Pakistan. Frontiers in Psychology 10: 2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathieu, Sharna L., Elizabeth G. Conlon, Allison M. Waters, and Lara J. Farrell. 2020. Perceived parental rearing in pediatric obsessive–compulsive disorder: Examining the factor structure of the EMBU child and parent versions and associations with OCD symptoms. Child Psychiatry & Human Development 51: 956–68. [Google Scholar]

- Mayorga-Lascano, Marlon, and Rodrigo Moreta-Herrera. 2019. Síntomas clínicos, subclínicos y necesidades de atención psicológica en estudiantes universitarios con bajo rendimiento. Revista Educación 43: 452–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J. H. F. 1995. Gender differences in the learning behaviour of entering first-year university students. Higher Education 29: 201–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyerson, Shari L., Joel M. Sternbach, Joseph B. Zwischenberger, and Edward M. Bender. 2017. The effect of gender on resident autonomy in the operating room. Journal of Surgical Education 74: e111–e118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Méndez, Francisco Xavier, Candido J. Inglés, and María D. Hidalgo. 2002. Estrés en las relaciones interpersonales: Un estudio descriptivo en la adolescencia. Ansiedad y Estrés 8: 25–36. [Google Scholar]

- Micin, Sonia, and Verónica Bagladi. 2011. Salud mental en estudiantes universitarios: Incidencia de psicopatología y antecedentes de conducta suicida en población que acude a un servicio de salud estudiantil. Terapia Psicológica 29: 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C. Dean, Jeff Finley, and Donna L. McKinley. 1990. Learning approaches and motives: Male and female differences and implications for learning assistance programs. Journal of College Student Development 31: 147–54. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, Catherine, and Juan Manuel Fernández-Cárdenas. 2018. Teaching STEM education through dialogue and transformative learning: Global significance and local interactions in Mexico and the UK. Journal of Education for Teaching 44: 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss-Racusin, Corinne A., John F. Dovidio, Victoria L. Brescoll, Mark J. Graham, and Jo Handelsman. 2012. Science faculty’s subtle gender biases favor male students. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109: 16474–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagy, Gabriel, Helen M. G. Watt, Jacquelynne S. Eccles, Ulrich Trautwein, Oliver Lüdtke, and Jürgen Baumert. 2010. The development of students’ mathematics self-concept in relation to gender: Different countries, different trajectories. Journal of Research on Adolescence 20: 482–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, Sadaf, Syed Afzal Shah, and Anjum Qayum. 2020. Gender differences in motivation and academic achievement: A study of the university students of KP, Pakistan. Global Regional Review 5: 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerín, Natalia Franco, Miguel Ángel Pérez Nieto, and María José de Dios Pérez. 2014. Relación entre los estilos de crianza parental y el desarrollo de ansiedad y conductas disruptivas en niños de 3 a 6 años. Revista de Psicología Clínica con Niños y Adolescentes 1: 149–56. [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema, Susan. 2012. Emotion regulation and psychopathology: The role of gender. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 8: 161–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2015. The ABC of Gender Equality in Education. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, Jonathan, Shirley Simon, and Sue Collins. 2003. Attitudes towards science: A review of the literature and its implications. International Journal of Science Education 25: 1049–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrelli, Paola, Maren Nyer, Albert Yeung, Courtney Zulauf, and Timothy Wilens. 2015. College students: Mental health problems and treatment considerations. Academic Psychiatry 39: 503–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perchtold, Corinna M., Ilona Papousek, Andreas Fink, Hannelore Weber, Christian Rominger, and Elisabeth M. Weiss. 2019. Gender differences in generating cognitive reappraisals for threatening situations: Reappraisal capacity shields against depressive symptoms in men, but not women. Frontiers in Psychology 10: 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piccolo, Luciane da Rosa, Adriane Xavier Arteche, Rochele Paz Fonseca, Rodrigo Grassi-Oliveira, and Jerusa Fumagalli Salles. 2016. Influence of family socioeconomic status on IQ, language, memory and executive functions of Brazilian children. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica 29: 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poorolajal, Jalal, Ali Ghaleiha, Nahid Darvishi, Shahla Daryaei, and Soheila Panahi. 2017. The prevalence of psychiatric distress and associated risk factors among college students using GHQ-28 questionnaire. Iranian Journal of Public Health 46: 957–63. [Google Scholar]

- Puskar, Kathryn R., Susan M. Sereika, and Linda L. Haller. 2003. Anxiety, somatic complaints, and depressive symptoms in rural adolescents. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing 16: 102–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raabe, Isabel J., Zsófia Boda, and Christoph Stadtfeld. 2019. The social pipeline: How friend influence and peer exposure widen the STEM gender gap. Sociology of Education 92: 105–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinking, Anni, and Barbara Martin. 2018. The gender gap in STEM fields: Theories, movements, and ideas to engage girls in STEM. Journal of New Approaches in Educational Research 7: 148–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, John T. E., and Estelle King. 1991. Gender differences in the experience of higher education: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Educational Psychology 11: 247–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, María del Carmen Aguilar. 2010. Estilos y estrategias de aprendizaje en jóvenes ingresantes a la universidad. Revista de Psicología 28: 208–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo, Mercedes Romero, Ángel San Martín Alonso, and José Peirats Chacón. 2018. Diferencias de sexo en estrategias de aprendizaje de estudiantes online. Innoeduca: International Journal of Technology and Educational Innovation 4: 114–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Hernández, Carlos Felipe, Eduardo Cascallar, and Eva Kyndt. 2020. Socio-economic status and academic performance in higher education: A systematic review. Educational Research Review 29: 100305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, Isabel María Vázquez, and Ángeles Blanco Blanco. 2018. Factores sociocognitivos asociados a la elección de estudios científico-matemáticos. Un análisis diferencial por sexo y curso en la Educación Secundaria. Revista de Investigación Educativa 37: 269–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, David, Kypros Kypri, and Jenny Bowman. 2013. Risk factors for mental disorder among university students in Australia: Findings from a web-based cross-sectional survey. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 48: 935–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, Dalia, Nathalie Camart, and Lucia Romo. 2017. Predictors of stress in college students. Frontiers in Psychology 8: 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Gregorio, María Ángeles Pérez, Agustín Martín Rodríguez, Mercedes Borda Mas, and Carmen del Río Sánchez. 2003. Estrés y rendimiento académico en estudiantes universitarios. Cuadernos de Medicina Psicosomática y Psiquiatría de Enlace 67/68: 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Saura, Cándido J. Inglés, María Soledad Torregrosa Díez, José Manuel García Fernández, Mari Carmen Martínez Monteagudo, Estefanía Estévez López, and Beatriz Delgado Domenech. 2014. Conducta agresiva e inteligencia emocional en la adolescencia [Aggressive behavior and emotional intelligence in adolescence]. European Journal of Education and Psychology 7: 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáinz, Milagros. 2020. Brechas y Sesgos de Género en la Elección de Estudios STEM: ¿Por qué Ocurren y Cómo Actuar para Eliminarlas? Seville: Centro de Estudios Andaluces. [Google Scholar]

- Severiens, Sabine E., and Geert T. M. Ten Dam. 1994. Gender differences in learning styles: A narrative review and quantitative meta-analysis. Higher Education 27: 487–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Yi, Meng Ji, Wenxiu Xie, Rongying Li, Xiaobo Qian, Xiaomin Zhang, and Tianyong Hao. 2022. Interventions in Chinese undergraduate students’ mental health: Systematic review. Interactive Journal of Medical Research 11: e38249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Laya, Marisol, Natalia D’Angelo, Elda García, Laura Zúñiga, and Teresa Fernández. 2020. Urban poverty and education: A systematic literature review. Educational Research Review 29: 100280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinath, Birgit, Christine Eckert, and Ricarda Steinmayr. 2014. Gender differences in school success: What are the roles of students’ intelligence, personality, and motivation? Educational Research 56: 230–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, Zachary, Claire Marnane, Changiz Iranpour, Tien Chey, John W. Jackson, Vikram Patel, and Derrick Silove. 2014. The global prevalence of common mental disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis 1980–2013. International Journal of Epidemiology 43: 476–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinhausen, Hans-Christoph, Nora Müller, and Christa Winkler Metzke. 2008. Frequency, stability and differentiation of self-reported school fear and truancy in a community sample. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health 2: 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmayr, Ricarda, and Ursula Kessels. 2017. Good at school = successful on the job? Explaining gender differences in scholastic and vocational success. Personality and Individual Differences 105: 107–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, Jennifer S., and Stephan Hamann. 2012. Sex differences in brain activation to emotional stimuli: A meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies. Neuropsychologia 50: 1578–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susperreguy, Maria Ines, Pamela E. Davis-Kean, Kathryn Duckworth, and Meichu Chen. 2018. Self-concept predicts academic achievement across levels of the achievement distribution: Domain specificity for math and reading. Child Development 89: 2196–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, Keith T. 2018. The Use of Cronbach’s Alpha When Developing and Reporting Research Instruments in Science Education. Research in Science Education 48: 1273–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TIMSS. 2015. Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study. Available online: https://bit.ly/3nuTsJP (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Tran, Antoine, Laurie Tran, Nicolas Geghre, David Darmon, Marion Rampal, Diane Brandone, Jean-Michel Gozzo. Hervé Haas, Karine Rebouillat-Savy, Hervé Caci, and Paul Avillach. 2017. Health assessment of French university students and risk factors associated with mental health disorders. PLoS ONE 12: e0188187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. 2019. Descifrar el Código: La Educación de las niñas y las Mujeres en Ciencias, Tecnología, Ingeniería y Matemáticas (STEM). Paris: UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- Vera-Villarroel, Pablo, Karem Celis-Atenas, Alfonso Urzúa, Jaime Silva, Daniela Contreras, and Sebastián Lillo. 2016. Los afectos como mediadores de la relación optimismo y bienestar. Revista Argentina de Clínica Psicológica 25: 195–202. [Google Scholar]

- Voyer, Daniel, and Susan D. Voyer. 2014. Gender differences in scholastic achievement: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin 140: 1174–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, Bridget A., Sarah Mitchell, Ruby Batz, Angela Lee, Matthew Aguirre, Julie Lucero, Adrienne Edwards, Keira Hambrick, and David W. Zeh. 2023. Familial roles and support of doctoral students. Family Relations 72: 2444–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Ming-Te, and Jessica L. Degol. 2016. Gender gap in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM): Current knowledge, implications for practice, policy, and future directions. Educational Psychology Review 29: 119–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittle, Sarah, Murat Yücel, Marie B. H. Yap, and Nicholas B. Allen. 2011. Sex differences in the neural correlates of emotion: Evidence from neuroimaging. Biological Psychology 87: 319–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkin, Herman A., and Donald R. Goodenough. 1981. Cognitive Styles: Essence and Origins. New York: International University Press. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. 2001. Fortaleciendo la Prevención de Salud. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. 2014. Invertir en Salud Mental. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. 2023. Gender and Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/gender#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- World Medical Association. 2013. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 310: 2191–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worrell, Frank C. 2014. Theories school psychologists should know: Culture and academic achievement. Psychology in the Schools 51: 332–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worsley, Joanne Deborah, Andy Pennington, and Rhiannon Corcoran. 2022. Supporting mental health and wellbeing of university and college students: A systematic review of review-level evidence of interventions. PLoS ONE 17: e0266725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Zhonggen. 2019. Gender differences in cognitive loads, attitudes, and academic achievements in mobile English learning. International Journal of Distance Education Technologies 17: 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, Peter, and Alexandra Iwanski. 2014. Emotion regulation from early adolescence to emerging adulthood and middle adulthood: Age differences, gender differences, and emotion-specific developmental variations. International Journal of Behavioral Development 38: 182–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1. Coping with Difficulties | 2. Effort | 3. Autonomy | 4. Understanding/Career Interest | 5. Social Context | 6. Bad Mood/Irritability | 7. Anxiety | 8. Apathy/Demotivation | 9. Lack of Attention | 10. Poor Achievement Expectations | 11. Academic performance | 12. Care Father | 13. Care Mother | 14. Control Father | 15. Control Mother | 16. Protection Father | 17. Protection Mother | 18. Educational Level—Father | 19. Educational Level—Mother | 20. Family Economic Levels | Ω | M | SD | Asymmetry | Kurtosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | -- | 0.36 ** | 0.05 ** | 0.24 ** | −0.06 ** | −0.67 ** | −0.62 ** | −0.71 ** | −0.65 ** | −0.68 ** | 0.18 ** | 0.11 ** | 0.21 ** | −0.21 ** | −0.23 ** | −0.15 ** | −0.11 ** | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.11 ** | 0.79 | 2.64 | 0.061 | −0.23 | −0.50 |

| 2 | −− | 0.26 ** | 0.30 ** | −0.09 ** | −0.15 ** | −0.12 ** | −0.33 ** | −0.43 ** | −0.26 ** | 0.25 ** | 0.10 ** | 0.09 ** | −0.08 ** | −0.12 ** | −0.02 | −0.04 | −0.06 ** | −0.06 ** | 0.02 | 0.72 | 2.44 | 0.61 | −0.01 | −0.58 | |

| 3 | −− | 0.43 ** | 0.06 ** | −0.02 | −0.06 | −0.11 ** | −0.05 ** | −0.07 ** | 0.18 ** | −0.03 | −0.06 ** | 0.06 ** | 0.09 ** | 0.09 ** | 0.08 ** | −0.06 ** | −0.02 | −0.08 ** | 0.72 | 2.51 | 0.66 | 0.09 | −0.54 | ||

| 4 | −− | 0.05 * | −0.11 ** | −0.09 ** | −0.25 ** | −0.16 ** | −0.25 ** | 0.18 ** | 0.05 ** | 0.07 ** | −0.02 | −0.04 | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.00 | 0.59 | 3.09 | 0.52 | −0.64 | 0.47 | |||

| 5 | −− | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.05 * | 0.02 | −0.18 ** | −0.04 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.04 | 0.05 * | 0.09 ** | 0.01 | 0.66 | 2.04 | 0.71 | 0.57 | −0.25 | ||||

| 6 | −− | 0.48 ** | 0.47 ** | 0.33 ** | 0.35 ** | −0.05 * | −0.04 | −0.11 ** | 0.12 ** | 0.13 ** | 0.13 ** | 0.08 ** | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.03 | 2.41 | 1.04 | 0.12 | −1.16 | ||||||

| 7 | −− | 0.43 ** | 0.30 ** | 0.36 ** | −0.07 ** | −0.01 | −0.10 ** | 0.11 ** | 0.12 ** | 0.13 ** | 0.10 ** | 0.02 | −0.03 | −0.06 ** | 3.04 | 1.03 | −0.70 | −0.76 | |||||||

| 8 | −− | 0.46 ** | 0.41 ** | −0.11 ** | −0.07 ** | −0.14 ** | 0.14 ** | 0.15 ** | 0.18 ** | 0.05 * | 0.07 ** | 0.02 | −0.05 * | 2.91 | 1.05 | −0.50 | −1.01 | ||||||||

| 9 | −− | 0.37 ** | −0.14 ** | −0.06 ** | −0.14 ** | 0.13 ** | 0.14 ** | 0.10 ** | 0.07 ** | 0.04 * | 0.02 | −0.02 | 2.65 | 1.09 | −0.14 | −1.28 | |||||||||

| 10 | −− | −0.23 ** | −0.11 ** | −0.14 ** | 0.16 ** | 0.17 ** | 0.09 ** | 0.08 ** | −0.06 ** | −0.06 ** | −0.09 ** | 2.26 | 1.10 | 0.33 | −1.21 | ||||||||||

| 11 | −− | 0.07 ** | 0.06 ** | 0.06 ** | −0.05 ** | 0.00 | −0.05 * | 00.03 | 0.02 | 0.06 ** | 2.01 | 1.04 | 0.64 | −0.84 | |||||||||||

| 12 | −− | 0.56 ** | −0.21 ** | −0.18 ** | −0.03 | −0.09 ** | 0.30 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.24 ** | 2.78 | 0.99 | −0.36 | −1.06 | ||||||||||||

| 13 | −− | −0.19 ** | −0.21 ** | −0.13 ** | 0.03 | 0.22 ** | 0.32 ** | 0.29 ** | 2.57 | 1.03 | −0.12 | −1.24 | |||||||||||||

| 14 | −− | 0.56 ** | 0.35 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.07 ** | 1.61 | 0.92 | 1.35 | 0.68 | ||||||||||||||

| 15 | −− | 0.26 ** | 0.33 ** | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.09 ** | 1.62 | 0.93 | 1.33 | 0.60 | |||||||||||||||

| 16 | −− | 0.57 ** | −0.02 | −0.04 | −0.05 * | 2.17 | 1.07 | 0.42 | −1.10 | ||||||||||||||||

| 17 | −0.04* | −0.01 | −0.01 | 2.00 | 1.01 | 0.64 | −0.75 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 18 | −− | 0.55 ** | 0.37 ** | 2.38 | 0.70 | −0.68 | −0.74 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 19 | −− | 0.40 ** | 2.36 | 0.71 | −0.64 | −0.80 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 20 | 3.01 | 0.81 | −0.29 | 0.39 |

| Range | Male | Female | Significance | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | M | SD | N | M | SD | |||

| Effort | 1–4 | 636 | 2.48 | 0.64 | 1.733 | 2.43 | 0.61 | F(3.35) * |

| Autonomy | 1–4 | 650 | 2.64 | 0.66 | 1.757 | 2.46 | 0.65 | F(34.04) *** |

| Understanding/Career interest | 1–4 | 653 | 3.12 | 0.52 | 1.765 | 3.08 | 0.52 | F(3.23) |

| Context | 1–4 | 656 | 2.02 | 0.74 | 1.773 | 2.05 | 0.70 | F(0.51) |

| Coping with Difficulties | 1–4 | 648 | 2.80 | 0.61 | 1.758 | 2.59 | 0.60 | F(56.31) *** |

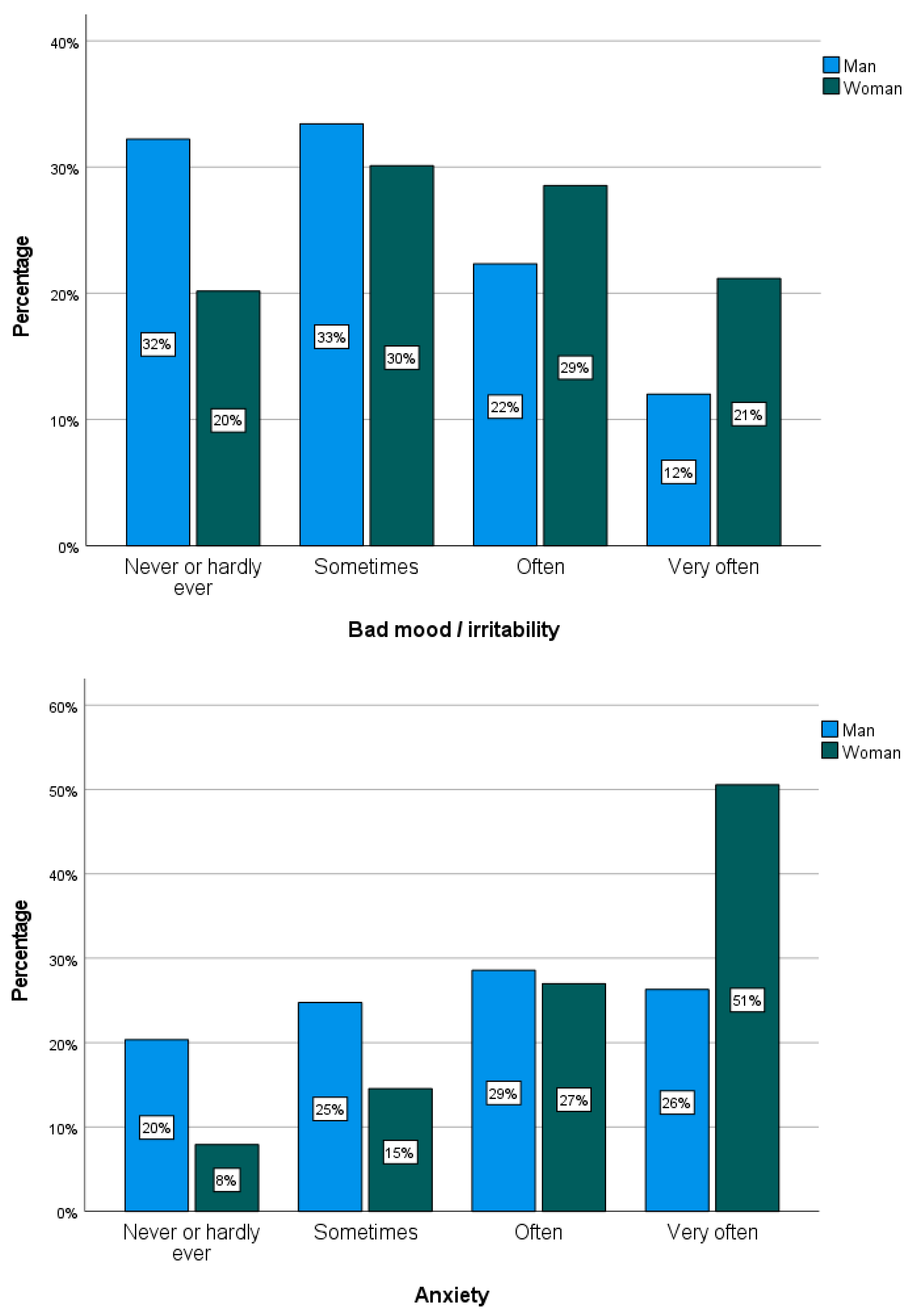

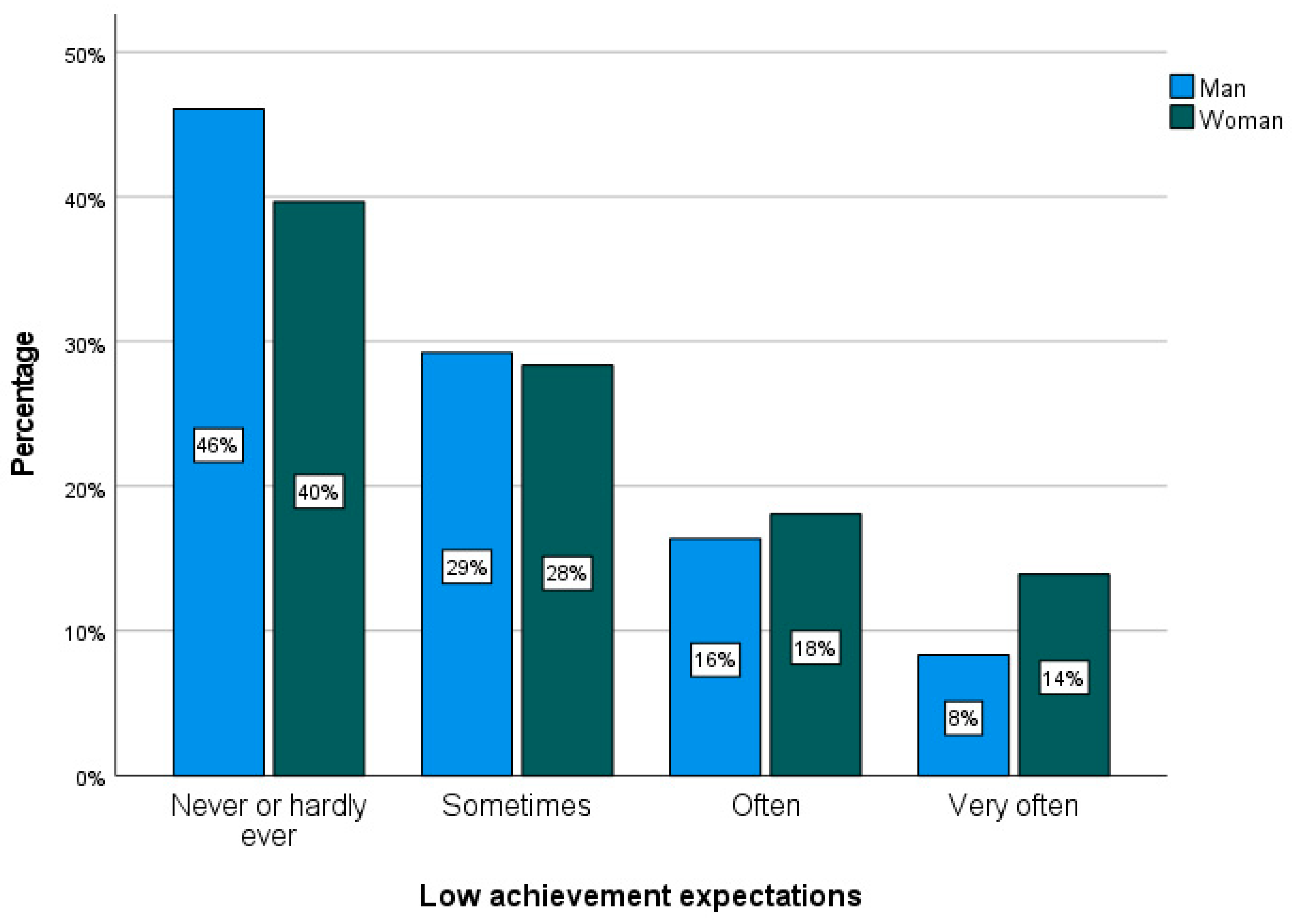

| Bad mood/Irritability | 1–4 | 658 | 2.14 | 1.00 | 1.780 | 2.51 | 1.04 | F(60.78) *** |

| Anxiety | 1–4 | 658 | 2.61 | 1.08 | 1.780 | 3.20 | 0.96 | F(170.40) *** |

| Apathy/Demotivation | 1–4 | 657 | 2.73 | 1.08 | 1.781 | 2.98 | 1.03 | F(27.94) *** |

| Lack of attention | 1–4 | 659 | 2.48 | 1.08 | 1.781 | 2.71 | 1.08 | F(22.21) *** |

| Low achievement expectations | 1–4 | 660 | 1.87 | 0.97 | 1.781 | 2.06 | 1.06 | F(16.64) *** |

| Males Coping with Difficulties | Non-Standarized Coefficients | Standarized Coefficients | t | Sig. | F | R2 | Sig. |

| B | Beta | ||||||

| (Constant) | 2.86 | 15.11 | 0.07 | <0.001 | |||

| Maternal Control | −0.09 | −0.13 | −2.74 | 0.00 | |||

| Maternal Care | 0.08 | 0.13 | 3.21 | 0.00 | |||

| Paternal Control | −0.08 | −0.11 | −2.38 | 0.02 | |||

| Effort | |||||||

| (Constant) | 2.59 | 48.17 | <0.001 | 6.62 | 0.01 | 0.01 | |

| Maternal Control | −0.08 | −0.10 | −2.57 | 0.010 | |||

| Autonomy | |||||||

| (Constant) | 2.47 | 41.61 | <0.001 | 10.29 | 0.01 | 0.001 | |

| Paternal Protection | 0.08 | 0.13 | 3.20 | 0.001 | |||

| Learning by Understanding/Career-focused | |||||||

| (Constant) | 3.03 | 64.46 | <0.001 | 5.32 | 0.01 | 0.021 | |

| Paternal Protection | 0.05 | 0.09 | 2.30 | 0.021 | |||

| Females Coping with Difficulties | B | Beta | t | Sig. | F | R2 | Sig. |

| (Constant) | 2.59 | 46.49 | <0.001 | 62.34 | 0.10 | <0.001 | |

| Maternal Care | 0.11 | 0.18 | 7.82 | <0.001 | |||

| Maternal Control | −0.10 | −0.16 | −6.84 | <0.001 | |||

| Paternal Protection | −0.05 | −0.09 | −3.99 | <0.001 | |||

| Effort | |||||||

| (Constant) | 2.34 | 42.46 | <0.001 | 20.67 | 0.02 | <0.001 | |

| Paternal Care | 0.06 | 0.10 | 4.17 | <0.001 | |||

| Maternal Control | −0.06 | −0.10 | −3.96 | <0.001 | |||

| Autonomy | |||||||

| (Constant) | 2.28 | 56.54 | 0.000 | 11.40 | 0.01 | <0.001 | |

| Maternal Control | 0.05 | 0.078 | 3.12 | 0.002 | |||

| Paternal Protection | 0.04 | 0.07 | 2.64 | 0.008 | |||

| Learning by Understanding/Career-focused | |||||||

| (Constant) | 2.96 | 87.59 | 0.000 | 13.62 | 0.01 | <0.001 | |

| Maternal Care | 0.05 | 0.09 | 3.69 | <0.001 | |||

| STEM | N | Mean | SD | ANOVA | ||||

| df | F | p | ||||||

| Coping with Difficulties | Male | 358 | 2.80 | 0.60 | Between groups | 1 | 21.49 | <0.001 |

| Female | 848 | 2.63 | 0.57 | Within groups | 1.204 | |||

| Effort | Male | 346 | 2.41 | 0.63 | Between groups | 1 | 0.21 | 0.650 |

| Female | 825 | 2.43 | 0.59 | Within groups | 1.169 | |||

| Autonomy | Male | 354 | 2.48 | 0.59 | Between groups | 1 | 8.58 | 0.003 |

| Female | 843 | 2.36 | 0.63 | Within groups | 1.195 | |||

| Learning by Understanding/Career-focused | Male | 361 | 3.08 | 0.50 | Between groups | 1 | 0.28 | 0.594 |

| Female | 851 | 3.09 | 0.50 | Within groups | 1.210 | |||

| Social Context | Male | 362 | 2.09 | 0.72 | Between groups | 1 | 3.64 | 0.057 |

| Female | 853 | 2.18 | 0.71 | Within groups | 1.213 | |||

| NON-STEM | N | Mean | SD | ANOVA | ||||

| df | F | p | ||||||

| Coping with Difficulties | Male | 229 | 2.51 | 0.58 | Between groups | 1 | 30.29 | <0.001 |

| Female | 804 | 2.34 | 0.55 | Within groups | 1.031 | |||

| Effort | Male | 229 | 2.35 | 0.59 | Between groups | 1 | 10.95 | <0.001 |

| Female | 798 | 2.37 | 0.58 | Within groups | 0.1025 | |||

| Autonomy | Male | 231 | 2.33 | 0.57 | Between groups | 1 | 29.45 | <0.001 |

| Female | 806 | 2.29 | 0.61 | Within groups | 1.035 | |||

| Learning by Understanding/Career-focused | Male | 229 | 2.98 | 0.49 | Between groups | 1 | 10.86 | 0.001 |

| Female | 805 | 3.01 | 0.50 | Within groups | 1.032 | |||

| Social Context | Male | 232 | 2.07 | 0.68 | Between groups | 1.033 | 0.05 | 0.82 |

| Female | 809 | 2.11 | 0.66 | Within groups | 1 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Elvira-Zorzo, M.N.; Gandarillas, M.Á.; Martí-González, M. Psychosocial Differences Between Female and Male Students in Learning Patterns and Mental Health-Related Indicators in STEM vs. Non-STEM Fields. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14020071

Elvira-Zorzo MN, Gandarillas MÁ, Martí-González M. Psychosocial Differences Between Female and Male Students in Learning Patterns and Mental Health-Related Indicators in STEM vs. Non-STEM Fields. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(2):71. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14020071

Chicago/Turabian StyleElvira-Zorzo, María Natividad, Miguel Ángel Gandarillas, and Mariacarla Martí-González. 2025. "Psychosocial Differences Between Female and Male Students in Learning Patterns and Mental Health-Related Indicators in STEM vs. Non-STEM Fields" Social Sciences 14, no. 2: 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14020071

APA StyleElvira-Zorzo, M. N., Gandarillas, M. Á., & Martí-González, M. (2025). Psychosocial Differences Between Female and Male Students in Learning Patterns and Mental Health-Related Indicators in STEM vs. Non-STEM Fields. Social Sciences, 14(2), 71. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14020071