1. Introduction

From 2015 to 2016, Europe received an unprecedented number of asylum applications, with more than 1.39 million applications recorded in 2015 and nearly 1.2 million in 2016 (

European Union Agency for Asylum 2016;

UNHCR 2017). Women and children together accounted for approximately 43% of those arriving during this period (

UNHCR 2016). In Ireland, 3275 individuals applied for international protection in 2015 and 2245 in 2016 (

European Migration Network 2017). Across the UK as a whole, 32,733 and 38,517 asylum applications were lodged in 2015 and 2016, respectively; however, Northern Ireland-specific data are not reported separately (

UK Home Office 2017). The cultural diversity and vulnerability of the new arrivals created significant public debate, regarding how those granted the right to remain will resettle their lives in their host societies. Creating a sense of belonging during their resettlement is integral to this process, to feel a sense of safety and security following violent displacement and to navigate complex legal processes (

Dromgold-Sermen 2020;

Keyes and Kane 2004;

Khan 2013;

Marlowe 2017). For many, this starts not with the host society, but with the creation of bonds with other refugees, particularly those of the same culture, ethnic group, or language group (

Easton-Calabria and Wood 2020). These relationships have been linked to the improvement in quality of life for resettled refugees (

Ager and Strang 2008). The understanding that displaced communities are often their own first responders (

Pincock et al. 2020) has permeated through policy and practice in humanitarian response, including United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees’ community-based protection approach (

UNHCR 2013) and the 2016 World Humanitarian Summit’s strong focus on ‘localisation’ (

Pincock et al. 2020). Despite consensus among global actors regarding the important role of communities in responding to their own emergency, following the process of displacement, network forming, or grouping together can be viewed as resisting the majority culture (

Prinz 2019) as well as a threat to native cohesion (

Ratković 2017).

Integration Policy in Northern Ireland and Republic of Ireland.

In the Republic of Ireland (ROI), homogeneity is prevalent in political discourse since the state’s inception, being strongly linked with ideas around nation-building (

O’Malley 2021). In Northern Ireland (NI), which remains part of the United Kingdom (UK), entrenched sectarian division within host communities provides a separate challenge for new arrivals trying to understand the culture and practices of a host society that lacks social cohesion (

Malischewski 2013;

Vieten and Murphy 2023). In response to the diversification of backgrounds within their populations, ROI and NI continue to develop state-led policies around resettlement of new arrivals. ROI’s Migrant Integration Strategy ascribes to a vision of migrants and refugees being facilitated to ‘play a full role in Irish society’ (

Government-of-Ireland 2020), through a series of elements covering cultural, social, economic, and political integration. The ROI National Integration Fund provides €750,000 in annual funding through competitive calls. The Migrant Integration Strategy outlines several dimensions of integration, including cultural (participation in local cultural life), social (building relationships and reducing isolation), economic (access to employment and education), and political (civic engagement and democratic participation). The NI Refugee integration strategy remained in draft from 2021 until 2025, when it finally outlined a vision for a cohesive and shared society.

Within both strategies there is little provision for two areas at the core of this research: the distinctive needs of refugee women in the process of resettling into their new lives, and the role that refugee networks might have in the experiences of a refugee or person seeking asylum in Ireland. Neither document makes reference to the unique challenges facing women refugees, except to be mentioned as a group vulnerable to human trafficking. Neither strategy directly references the formation of networks specifically for recognised refugees and asylum seekers, or the role these groups could have in the life of a recognised refugee or person seeking asylum on the island of Ireland.

With NI navigating a fragmented society through a fragile coexistence and ROI, redirecting itself from a century of homogenous nation-building to an agenda that ‘enables Irish society to enjoy the benefits of diversity’ (

Government-of-Ireland 2020), the intersectionality of being a woman and a refugee requires thought beyond the complexity considered in either of the aforementioned strategies.

1.1. Women Refugee Networks

Questions remain about how a sense of belonging and cohesion within a community of refugees is formed, particularly from the perspective of women refugees. As

Peace and Meer (

2019, p. 20) noted, ‘the particularity of refugee women’s experiences remains overlooked in a male-centred paradigm’. Women’s networks play a central role in the creation of a new life for refugee women (

Keyes and Kane 2004). Firstly, these networks provide structure in a new environment, enabling access to services and basic needs. Women from minorities are more likely to seek out sources of leadership and organisation within their communities to access services (

Yong and Germain 2022) and to negotiate on their behalf regarding gender and child issues, relating to both problem solving and aspirations (

Zetter et al. 2006). Social networks enable women to obtain knowledge of upcoming opportunities as well as negotiate around discriminatory bias in places of employment and the wider society (

Yang et al. 2019). This is an ability even more pertinent to refugee women who are more likely to encounter discrimination due to both their gender and immigration status (

Wimalasiri 2021). Yet, women have significantly fewer opportunities to access these networks due to care-giving responsibilities (

Liebig and Tronstad 2018).

Secondly, networks promote a sense of belonging (

Ager and Strang 2008). Providing an environment for free expression for refugees is central to their feelings of safety (

Elliott and Yusuf 2014). Women-only safe spaces are a common practice in humanitarian responses and are seen as a critical service for a population with distinct psycho-social needs (

Wimalasiri 2021). For example, women refugees are at increased risk of suffering both physical and mental health difficulties (

Peace and Meer 2019;

Shishehgar et al. 2017) and are more likely to experience social isolation (

Shishehgar et al. 2017). Humanitarian actors view women-only safe spaces as a chance for displaced women to seek and receive help but also to commune with one another (

UNICEF 2021). Moreover, conversations and friendships between women foster belonging (

Green 1998), empowerment, and assist with healing (

Comas-Diaz and Weiner 2013). The necessity for sharing of experiences among other women refugees, and building friendships with them, has the impact of creating ‘the ‘we-ness’ of shared phenomena’ (

Keyes and Kane 2004), which reduces loneliness and increases a sense of safety. Storytelling has long been viewed as an effective therapeutic tool by assisting catharsis (

Rennie 1994); but particularly for women, due to more fragmented experiences of trauma through displacement (

Aron 1992).

1.2. Current Study

The current study aimed to understand the contributing factors to cohesion in women’s refugee networks. Previous research has focused on the influence of community building, within refugee populations, on broader state-led integration agendas. We aimed to extend this work by understanding the process of cohesion itself, as we unpack the methods and influences within networks of refugees. We explored participants’ lived experiences of how and why relationships were formed among networks and the day-to-day tasks of participating, maintaining, and future planning for each network. We examined the benefits of cohesive communities of women from the perspective of the women who built them. Through the narrative accounts of our participants’ lived experiences, we can understand group cohesion and the broader resonance it has in their lives.

3. Procedure and Data Collection

Between October 2021 and March 2022, we collated a database of women refugee networks on the island of Ireland through outreach to civil society organisations and contacting refugee-friendly forums on social media. We contacted fifteen organisations and four agreed to participate in the study. Of those that did not participate four were not suited to the study (n = 4, e.g., not gender-specific network or not refugee-specific), four did not wish to participate or did not respond (n = 4) and the remainder could not accommodate participation in the given timescale (n = 3). Within the four participating networks, we conducted recruitment through a mixture of open calls for participants shared at meetings and via WhatsApp, as well as through friend referrals following the initial interviews in each network. Semi-structured interviews took place between late March to June 2022. Participants provided both written and verbal consent regarding the terms and parameters of the research, and the use of data collected from their interviews.

3.1. Participating Networks

All participating networks employed someone in a paid position of network organiser/facilitator.

Network 1 (N1) is an urban women’s group which was founded in 2002 in ROI. It is funded by European Union funding. Many members joined via state-run refugee referral systems, with the remaining being recruited by friends. Members are all city-based and most are no longer living in state-run reception centres. The group meets once a month, with members free to drop-in on a weekly basis to a city-centre office. Meetings consist of an informal group discussion and activities (e.g., card games, bingo, and family outings). Childcare is not provided but children are included in excursions. N1 participants were the most diverse group with six participants, from five different countries of origin in Africa and Central Asia. There were five different first language groups among the members who participated.

Network 2 (N2) comprises a women’s coffee morning founded in 2018 in ROI and funded by the local and national government. N2 has a subgroup running a social enterprise, founded in 2020, and funded by social innovation funding and local enterprise funding. Members were mainly recruited by organisers and friend referrals in their shared accommodation. Meetings are held in a city-based civic building, but most members live in rural state-run reception centres. Meetings occur on a weekly basis and consist of a coffee morning, education programme, and inter-county excursions. Members receive transportation to the civic building and childcare is provided. Social enterprise meetings are often held online in the style of a committee format, with trips to seasonal markets to sell their products. There were thirteen members of N2 participating in the study, from Africa and Europe, and seven first language groups. More than 60% of participants were from Nigeria but came from four different first language groups.

Network 3 (N3) is urban women’s collective which was established by its members in 2019 in NI. It is funded by the UK National Lottery and other charitable organisations. The founding members met through involvement in another civil society organisation. Participants live in a mixture of private and refugee accommodations within the city. Members attend one to three times per week in a community centre hosted by a civil society group. Childcare is provided during meetings and many projects are organised with the expectation that children will participate. Goods produced from projects are sold at a market. Seven members of N3 participated, from Africa, Middle East, and Central Asia, and there were three first language groups.

Network 4 (N4) is a regional refugee women’s network founded in 2019 in NI. It is funded by a project fund supported by a collective of charitable organisations. Founding members were recruited directly by the network organiser or friend referrals. Members live in a mixture of private and refugee accommodations. The network meets three to four times annually and informal drop-ins occur at the network’s permanent office. Participation in the network takes the form of family inter-county excursions, referrals to external education courses, weekly fitness meetings during lockdown, and one-on-one communication with the network organiser for vouchers and assistance. Childcare is not provided but children are included in excursions. In N4, 14 members participated from East Africa, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia, and there were three first language groups. This was the only participant group with one dominant language group; 78% of participants spoke Arabic as a first language.

3.2. Participants

Forty adult women from four different refugee networks located in Ireland in the provinces of Leinster, Munster and Ulster participated (

n = 40) and 30% of those used an interpreter to conduct the interview (Albanian

n = 2, Yoruba

n = 1, Arabic

n = 8, Kurdish

n = 1). Interviews requiring interpretation were conducted using consecutive translation, with interpreters providing an English rendering of participants’ responses in real time. Transcriptions were based on these English-language translations. Interviews ranged from approximately 25 to 70 min. They were conducted at locations chosen by participants, including their homes, community centres where the networks meet, or other neutral spaces. All participants were mothers with dependants, one was a grandmother with a dependent grandchild, and one network included both grandmothers and adult daughters. The size of the sample (

n = 40) was determined by the aim to represent the diversity of refugees and asylum seekers in Ireland and to achieve ‘adequate information power to develop new knowledge’ (

Malterud et al. 2016, p. 1759). This sample size allowed for exploration of a broad range of experiences and views within each network.

Table 1 summarises demographic information on the participants. The researchers followed the advice of

Mackenzie et al. (

2007, p. 306) who cautioned ‘to reflect carefully on ways to build and sustain that trust’ when conducting research with refugees. We made a conscious decision not to collect personal information from participants, as this could jeopardise the process of trust-building between the participant and the interviewer (

Mackenzie et al. 2007). The organisations that agreed to take part, advised that their members were regularly canvassed to participate in research, and were often required to describe experiences of fleeing their home countries and coming to Ireland. The researchers recruited participants for this study on the basis that the discussions would centre around participation within their networks and relationships built with other members. Length of membership and residency in Ireland were considered relevant to their participation in networks, to understand how soon members entered their network following arrival in Ireland. Country of origin and first language was requested to understand diversity of membership within networks, and caring responsibilities were discussed to consider time demands on participants lives. Interviewers collected demographic information at the beginning of the interview when trust-building was at a critical juncture. During this time the researchers did not gather information such as religion, marital status, or age, to navigate around potentially value-laden understandings of status characteristics for women (

Leavy and Harris 2019) across a wide range of cultures. The researchers aimed to show respect to the experiences of all participants as equal members of their networks. To protect confidentiality in small communities, individual demographic characteristics (e.g., ethnicity or country of origin) are not reported. Quotations are labelled using a network-and-participant index (e.g., N1, P3), which enables readers to follow individual contributions while safeguarding anonymity in small communities.

3.3. Data Analysis Procedure

We used six phases of reflexive thematic analysis (

Braun and Clarke 2019,

2022) to analyse the data. The present research was conceptually driven from a social constructivist paradigm informed by phenomenological position. Excel was employed to organise codes, subthemes, and themes. This was an iterative process, where phases overlapped and repeated to understand how the data responded to our research question. The first author led phases 1–3 of Braun and Clarke’s reflexive thematic analysis, including familiarisation with the data, generating initial codes, and developing preliminary themes. These were reviewed and discussed with the third author. Phases 4–5, involving theme reviewing and refinement, were completed collaboratively between the first and third authors. The second author provided interpretive oversight and reviewed the final thematic structure.

3.4. Researcher Reflexivity

This research was conducted within the discipline of psychology. All authors are residents in Ireland and therefore members of the host community. The first author in this research is a white Irish woman. She has worked in post-conflict political engagement in the Middle East and North Africa, and has worked as a humanitarian emergency responder, in Europe, Asia, and Africa, specialising in community engagement. A reflexive journal was maintained throughout the research process. The second author is a white Greek woman, whose expertise lies in health and developmental psychology. Her research focuses on resilience and youth well-being, employing advanced methodologies to examine the interplay of social, environmental, psychological, and biological factors in adversity. The third author is a white American woman with Irish Citizenship. Her research adopts an intergroup developmental lens to examine risk and resilience in children, families, and communities affected by prolonged conflict.

4. Results

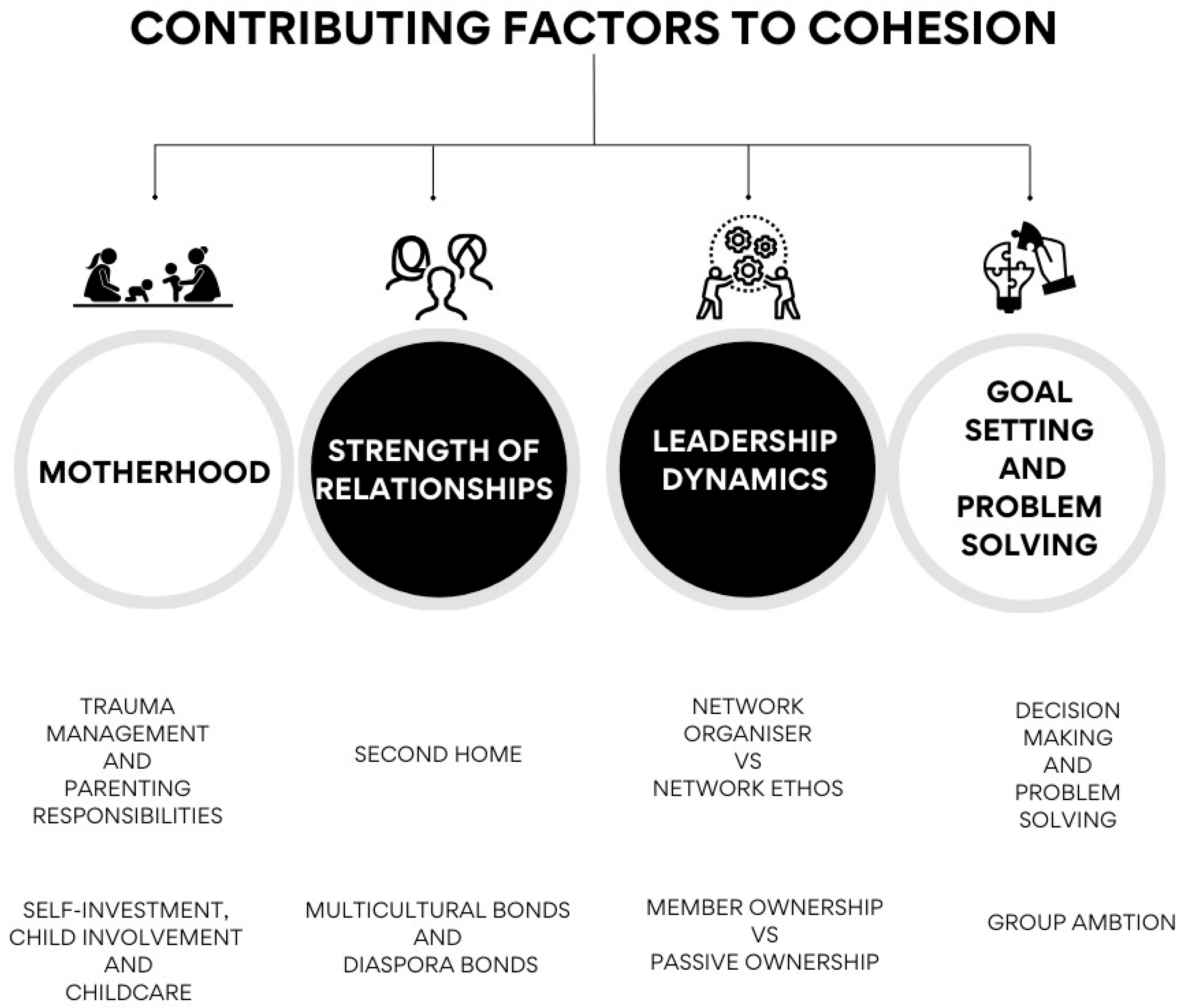

Figure 2 presents the thematic map of the interrelations among the themes identified in the data. Presented first in this paper are the themes,

Motherhood and

Strength of Relationships, which relate to the networks’ interaction and effect on members’ lives. Subthemes are presented chronologically, illustrating how a motherhood identity shaped entry and influenced network participation and how relationships were subsequently built from this starting point. The next two themes,

Leadership Dynamics and

Goal Setting and Problem Solving, relate to the networks’ structure and practices. Subthemes are presented to show contrasts between function, interpersonal relationships, and other defining characteristics within networks; with the most significant difference explored first. N2 will be discussed using parenthesis, where necessary, to denote if comments are referring to members only taking part in the umbrella group (coffee morning) or who were also involved in the subgroup (social enterprise).

4.1. Motherhood

All participants were mothers. Network entry was strongly connected to participants’ responsibilities as mothers (e.g., Trauma Management and Parenting Responsibilities); as such, support to them as mothers, affected members’ network engagement (e.g., Self-investment and Childcare).

Trauma Management and Parenting Responsibilities. Participants from all networks described feelings of emotional distress prior to entering the network. The need for support in coping with caring responsibilities motivated most members to join. The responsibility of their roles as mothers was mentioned as an additional pressure on the complications of being a newcomer.

“The woman who arrived here, mostly she will arrive exhausted. She is strong, sure, because no normal single woman could come here by herself [alone]. She must be very, very strong to arrive here. Once she arrives, I am sure most of the women … have a trauma, or a hard experience. Her or her children. Maybe she needs more support. She’s suffered from maybe problems, mentally, and she, like me, when I arrived, I felt lost. Where have I to start? Where have I to go?”

[N4, P13]

The challenge of addressing trauma management through membership of a women’s network was implied by participants across all networks but was explicitly stated by all participants from N3.

“And you know, all the trauma around my leaving was still very much on my head. Nobody to talk to, it’s just me and these children, and they will both leave for school. I’m left alone in the house.”

[N3, P4]

Across all networks, participants spoke about the difficulty of managing their trauma without familial support. Members equated their entry into the network as a substitute for such support.

“I have a big family back home, but they never went to another country. I was the first. And it was for me a big shock… And before coming here [to the network] I would be every night crying. I’d want to go back [home]. But I cannot go back. I have a family [here], I have [responsibility]. But since coming here I forget. Women come here with home problems, health problems, kids’ problems. [N1] will help.”

[N1, P5]

Self-Investment, Childcare, and Child Participation. Members in each network described their point of entry into the network as a choice that supported their existing agency, a moment of self-investment which could positively contribute to theirs and their family’s futures. There were clear similarities between N1 and N4, which differed from N2 and N3 in how this process was supported.

In both N1 and N4, members were often provided with outside referrals for further education, such as language classes, and offered support in making connections with places where members might improve pre-existing skills and qualifications.

“5 years at home with the children and I started to lose my skills [as a hairdresser]. [Network organiser arranged for her to get work experience to renew her skills] And working is good for me for my kids, for my family… gives a second life for people who come here.”

[N1, P5]

“[Referring to the benefit of membership] for sure it’s for learning, and then they get some skills and so that would be beneficial for them in future lives, for their job searching.”

[N4, P12]

In N2 and N3, there was an in-house approach to offering members further education. Members from N2 repeatedly referenced how important learning new skills was to them in their sense of hope for the future.

“I see women going there, with no hope before of anything, so when they go there, definitely they have courage, of holding onto something, like they have hope, [are] not hopeless.”

[N2, P9]

In N3 members contributed to each other’s education through a skills-sharing programme and, where appropriate, children were included in learning too. Members viewed this practice as mutually beneficial and therefore contributing to the creation of a community which supports itself.

“So we thought about why don’t we create something for us to help each other, we don’t need just to search for support, we can support each other. We are the people who created, you know, the women’s collective. We came with the idea.”

[N3, P5]

Although the outsourcing or in-house approach to members’ development varied, providing childcare or child involvement in all networks was described as pivotal in members being able to attend and feel supported.

“The trips, [are] for the kids especially, I think. And for us, the mummies, to get a chat and spend time.”

[N4, P10]

The provision of childcare in N2 and N3 enabled participants to attend the networks, providing time and space to benefit from their support.

“Please can I rest for three hours, you know, sometimes you need it, like you can just leave your kids and just for you to rest for three hours, for you to get your sanity back, you know?”

[N3, P1]

4.2. Strength of Relationships

This theme captures the types and depth of network relationships including how friendships can form a second home and the different types of bonding among members.

Second Home. Many participants described their networks as a second home. Yet, whether the network connected with their personal life varied widely: from keeping the two separate, to seeing the other members as a surrogate family.

In N1, for example, although participants discussed the desire to create a new community for themselves, members rarely saw each other outside of the network. In N1, friendships inside and outside of the network were separate, with those outside of the network more likely to be members of their own diasporas. In contrast, members of N4 spent significant time together outside of network activities. Despite these different levels of intimacy, both networks were regarded as a safe place by their members.

[Following discussion of fear of discrimination against their children by law enforcement] “When I have problems, I come here and speak with the girls.”

[N1, P5]

“We feel safe inside [N4] … Keep me safe, not allow other people to make me feel like a foreigner. If something happens to me, I straight away come [to N4] … If something that happen to me, I’m not calling the police, I will straight away call [N4].”

[N4, P2]

In N2(social enterprise) network bonds extended outside of the network setting and were brought back to the reception centre in which they were staying, to form a ‘sisterhood’.

“But friendship was built from the coffee morning to DP [Direct Provision—State-run reception centre]. Because we’re all from different countries. Even though we’re living in the same place. And we have our different beliefs and values, but the centre [network] allows us to identify what we have in common. And we start friendships. It’s kind of like a sisterhood now.”

[N2, P5]

In addition, nearly all the participants in N3 referred to their network as their family. Most of the stories of N3 members’ points of entry into the network suggest that they were seeking community by joining.

“I need to have friends. My family, my husband is not enough to continue life in a new country.”

[N3, P6]

Multicultural vs. Diaspora Bonds. In the early days of membership, members focused on meeting women from their own diaspora, citing shared language and culture as key connectors. Yet, a strong cohort of participants viewed making multicultural bonds within the network as evidence of their integration into life in Ireland.

Every member of N1 explained that their close friendships lay within their diaspora, but that if any member needed assistance, the network would be the first to help.

“[N1] has a big heart. You’re Syrian, you’re black, you’re white and the group will help.”

[N1, P5]

The need to meet people of the same race or nationality was important to many members of N2 at the beginning. Newer members recognised that they had not yet established friendships within the network outside of their own diaspora. There was a sense of members needing diaspora as a foundation before creating multicultural bonds.

“[After] going to lots of the meetings, with other women, interacting and speaking out, like, seeing different people, different cultures, their way of doing things, it really, it had a great impact. Yeah, the group touched my life and I really enjoyed going there, because I learned a lot there.”

[N2, P9]

Differing from N1 and N2, N4 and N3 displayed much more established multicultural bonds. N4 provided bonding experiences through excursions; but it should be noted that a large diaspora group existed within the participant group and nearly 80% spoke Arabic as a first language. Nevertheless, many participants stressed how multicultural the network is and how it had provided opportunity to create friendships across nationalities.

“It helps us to meet new people, you know to get connected with other people as well. You know people who come from different backgrounds, different race, different countries. So, it makes us unite… that we come for the same reason, you know, to have protection.”

[N4, P14]

In addition, N3 promoted an ethos of equality by actively incorporating members’ diverse cultural practices into shared activities and the goods they produced.

“Every woman from any country, they bring some spice … and every woman puts a touch, her touch, in the product.”

[N3, P3]

4.3. Leadership Dynamics

The theme of Leadership Dynamics has the most significant variation in participants’ accounts to demonstrate the differences between their networks and how they operate. This theme captured the influence of paid network organisers compared to a guiding network ethos and how levels of members’ ownership differed across networks.

Strong Network Organiser vs. Network Ethos. Participants from all networks mentioned the importance of the central paid organiser. However, less importance was placed on the role of the organiser in networks where participants demonstrated a clear understanding of the networks’ ethos.

On the one hand, participants from N1 and N4 were more likely to have equated the benefit of their membership to the level of assistance provided by organisers. In many cases the network organisers had gone to great lengths to help their members, engendering strong feelings of friendship and loyalty.

“Like bringing family [to Ireland]. She’s the one who did everything for my children to make sure they get safe.”

[N1, P6]

“In different areas. Like when we need something or need help, we ask [names N4 organiser] and she’s straight away happy to help us.”

[N4, P2]

On the other hand, in the case of N2 and N3, the organisers had a less central role. Members expressed gratitude for organisers having introduced them to the network or troubleshooting challenges, rather than continuing to identify the organiser as a benefactor. In these two networks, almost all participants referenced a network ethos. Participants across both groups implied a common understanding of their network as a place where help should be both given and received.

“And people have different responsibilities, so we have to work and come together. Okay, so it’s kind of like collaborative work, right?”

[N2, P5]

“Number one thing we stress in [N3] equality… Your religious belief is outside [of the network]. We take all of us. We used to cook together in every meeting, and you know the Muslim faith does not take any meat that is not prayed upon. They call it halal. So, when we are cooking, we’re cooking with a consciousness that some people can’t eat [certain ingredients]. So, you’re obligated that when you make your meal, either to cook without those kinds of foods in. Or you seek to go to Halal shop.”

[N3, P4]

Member Ownership vs. Passive Membership. There was a clear variability in the level of member ownership, with N3 having displayed the highest ownership and N4 having displayed the most passive membership. For example, members of N3 showed pride in the group’s grassroots origins which stemmed from a desire to support each other.

“As a volunteer, I started from that day. And I’m so happy. It’s a volunteer job; I don’t have to go there. We try our best. I myself, I try my best to have the best community because I enjoy it and I work to make it better there.”

[N3, P6]

N2 presented an interesting paradox as it housed two groups under the same leadership, both with a guiding ethos, but membership displayed very distinct forms of participation. The key difference between these groups was the way in which they were formed and the agendas which they operated under. Members of the coffee morning were less likely to express ownership of the wider network. Participation was passive rather than active or stakeholder-driven.

“They took them to different places and do nice, nice things. That’s it!”

[N2, P11]

Similarly, members of N1 and N4 mostly described gratitude for the help they have received, rather than expressing a responsibility to progress a more complex agenda.

“I found they are friendly, they are opening their heart to me, they are opening their hand to provide me support, to make me happy.”

[N4, P11]

4.4. Goal Setting and Problem Solving

In the theme Goal Setting and Problem Solving, subthemes Decision-Making and Problem Solving and Group Ambition are presented in order of the most significant contrast between networks.

Decision-making and Problem Solving. Participants discussed how decisions were arrived at regarding network operations and activities. There was a link between networks where members influenced the decision-making of the group and the potential for disagreements to arise. Approaches to decision-making ranged from a formalised method of group decision-making in N2 (social enterprise) and N3, to a practice of network organisers driving decisions in N2 (coffee morning) and in N4.

First, N2 (social enterprise) and N3 were structured in the form of a committee. Both groups held an open forum and made decisions by consensus or a majority vote, if necessary. Members from both networks held the opinion that being part of the organisation required a member to voice their opinion.

“As long as I am doing something for the Group and the Group like it, I have the right to give my opinion, something that will be accepted.”

[N2, P8]

“Every time they ask us about a new idea, if you have any, anything to [add}, for improving our project. Because it’s not a project for someone, it’s for all the women.”

[N3, P3]

N2 (social enterprise) and N3 spoke openly about disagreements arising while building their networks. N2 (social enterprise) members spoke about relying on a team of advisors from other organisations to weigh in on decision-making and provide clarity to group negotiations. N3 members credited the network organiser with possessing a mediating presence during times of disagreement. Yet, overwhelmingly, participants reiterated a group ethos of mutual respect and equality in group discussions as a way of navigating potential disunity.

“And we see differences of opinion, all the time there. But they are kind and they try to be kind. If anything happens, we say please come here, we speak, and we want to solve it to have the better communication.”

[N3, P6]

Second, N1 had a less formal structure to meetings but members conversed freely and felt confident to influence how they spent their time together. It was generally stated that disagreement was not a common occurrence but occasionally happened when choosing group activities.

“We put it on the table and we decide and say, ‘Okay, let’s go to so so place’ or ‘let’s do so so’.”

[N1, P6]

Finally, N2 (coffee morning) and N4 differed greatly in structure, but members presented a very similar response to the idea shaping decision-making. Members trusted that they could speak freely and ask questions in their networks, but decisions were made by the network organisers and members did not express a desire to act autonomously. N4 and N2 (coffee morning) unanimously said that disagreement was not a feature of their networks.

“Of course they would listen to me but it never happened [like] that, never said like ‘I don’t like to go to that place’, or ‘change that place’. But of course, if I say it they would listen to me.”

[N4, P5]

Group Ambition. Overall, there was a strong commonality in goal identification, such as their hopes for the future of their networks, within N1, N2, and N3; N4 showed less uniformity. This subtheme revealed quite distinct network identities. N1, being the oldest established group, expressed a desire for continuity of services. For the first time in this theme, N2 showed consensus between its groupings, with their wish to effect change and contribute to society.

“And I think the core thing for me is to change the narrative about people migrating and the [local] community, coming to Ireland… we want to say ‘Okay, we have these skills, and we want to contribute.”

[N2, P5]

The idea of influencing change was similarly desired by N3. For members of N3, this took the form of influencing societal decision-making.

“Influence! … I pray they will have so much grant(funding) that they could influence things that happen in the Community.”

[N3, P4]

N3 also voiced very specific aims to specialise in one of their key services of professionalising their provision of psycho-social support. It was evident that this group had discussed future-planning together.

“We are thinking about trauma, and I’d like if people can solve their problems in this community. And they can speak for the trauma, when they join, to this Community.”

[N3, P6]

In contrast, N4 had a less unified response. N4 members expressed a wide variety of hopes, which could be summarised as a general desire for diversification of services. Broadly speaking this group hoped for expansion and access to a wider variety of services.

“I wish if they can give us a day in a week to let all the women to gather together, come to sit, and they have a coffee, chat together. To know each other and exchange ideas and things, talk about their experience.”

[N4, P13]

5. Discussion

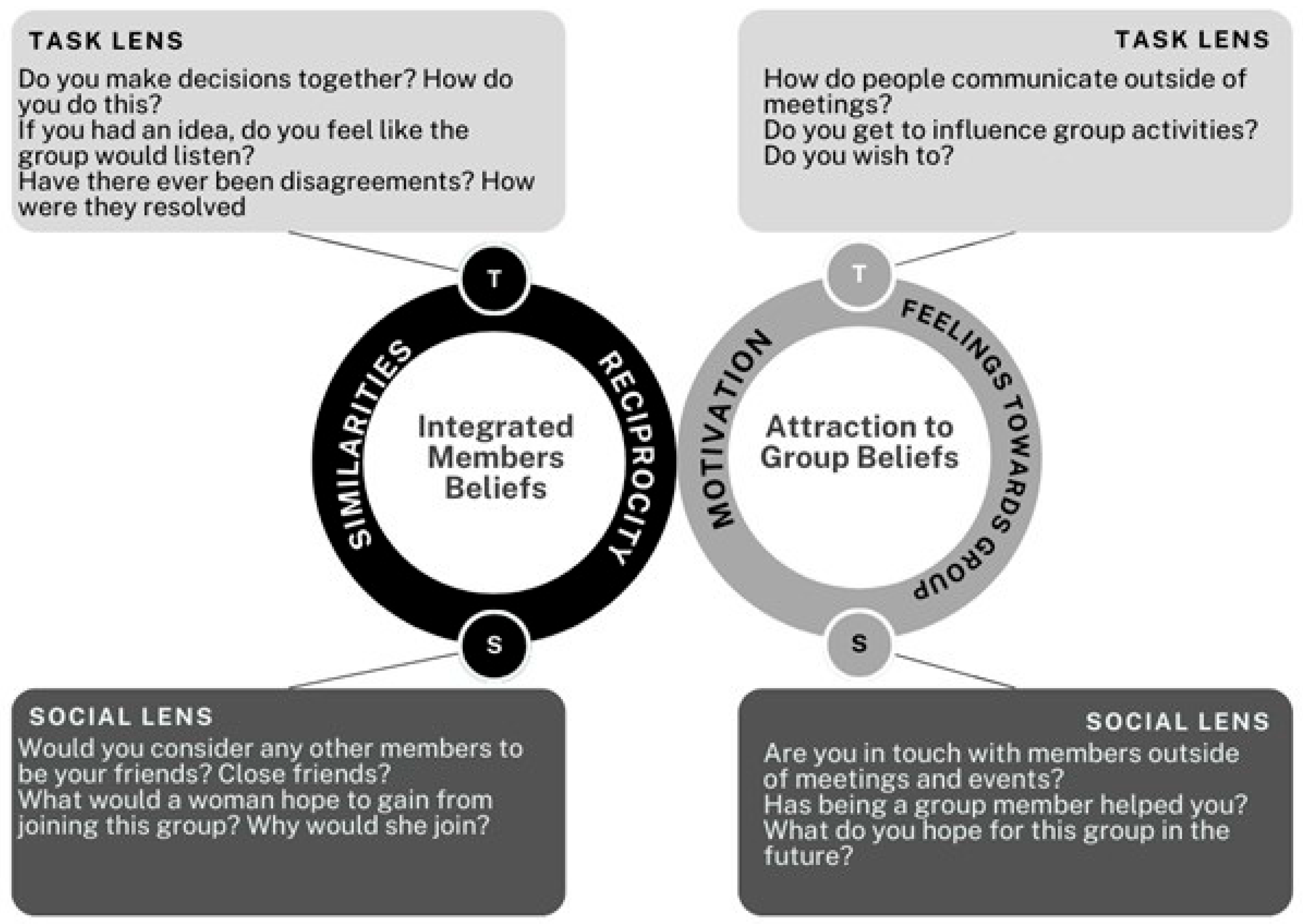

The analysis was guided by the conceptual framework in

Figure 1, which distinguishes social and task-related dimensions of cohesion. This framework informed the development of the interview guide and shaped the areas explored with participants. The themes presented below therefore reflect aspects of cohesion that emerged through this framework-led inquiry.

We aimed to understand the contributing factors to cohesion in women’s refugee networks. Extending previous research on refugee community building, we examined the lived experiences of network formation among refugee women, through 40 in-depth interviews with participants from four networks across Ireland. Overall, we identified four contributing factors to cohesion: Motherhood, Strength of Relationships, Leadership Dynamics, and Goal Setting and Problem Solving.

Network cohesion was strengthened through building services around

Motherhood identity and responsibilities. Across all groups, cohesion was built by being flexible in responding to members’ needs. Networks’ acknowledgement and support of participants’ dual identities, as both refugee women and mothers were crucial. For example, networks which facilitated the sharing of experiences of displacement trauma and motherhood, allowed their members to relate to each other’s stories, forging bonds and fostering a sense of belonging. Supporting members to exercise their existing skills and capacities through further education was an element in all networks, but in networks where education and childcare were provided in-house, participants availed of more opportunities. Across all networks, participants equated their need to address experiences of trauma (

Peace and Meer 2019;

Radowicz 2021;

Shishehgar et al. 2017) with their need to function as mothers. In doing so, members acknowledged their own mental health vulnerability and saw participation as a way of mitigating against previous adversity.

Second, creating an atmosphere where

Strength of Relationships could be forged through reciprocal support allowed members to build a sense of belonging (

Keyes and Kane 2004). The connections created between members, support the idea of a healing power in female friendships (

Comas-Diaz and Weiner 2013). Many members expressed a preference for building friendships among people of the same ethnicity, or at least language group. Yet, most networks found ways to move beyond this, with grassroots networks more likely to establish practices which normalised heterogeneity within friendship groups (

Easton-Calabria and Wood 2020). Moreover, participants sought to build a ‘second home’ in these networks, particularly in grassroots organisations; members aimed to foster a surrogate family to replace what had been lost through displacement.

Third, building on the previous literature,

Leadership Dynamics provided by an organiser or a guiding ethos, fostered cohesion. This finding is consistent with the need for purposeful interventions to promote cohesion in refugee groups because of the changing composition of the population (

Daley 2009). A strong network organiser can create a safe environment for refugees to share their experiences (

Elliott and Yusuf 2014) and to form bonds with other members. Moreover, grassroots organisations may evolve from an initial intervention and foster deeper levels of cohesion. Networks in which members verbalised a strong network ethos, also showed higher levels of member ownership. Membership was more likely to be passive in networks which had a strong network organiser and a less demonstrable guiding ethos.

Finally, leadership also had implications for

Decision-Making; networks with higher members’ ownership had increased capacity for recognising and resolving disagreements within the group. A similar pattern was directly reflected in the group’s

Goal Setting; networks with higher members’ ownership had clearer, more unified goal selection. Identifying collective obstacles was linked with a higher expectation that the network could achieve its goals (

Carroll et al. 2005). In other words, ambitious goal setting is consistent with stronger collective efficacy (

Bandura 1995). Networks which organised through committees, in which members participated in decision-making, were more likely to have ambitions for community campaigning and outside projects. That is, organised network facilitation fosters solidarity to participate in wider societal pursuits (

Elliott and Yusuf 2014;

Zetter et al. 2006).

5.1. Limitations and Future Research

All participants were offered interpretation to conduct interviews, but many wished to conduct theirs solely in English. In the future it would be preferable for interviews to take place in participants’ first language, where possible. This would allow participants to express complex experiences with greater ease and nuance and would likely strengthen the depth and richness of the data. Furthermore, this study focused on cohesion within women’s refugee networks; future research could examine the implications of such cohesion on the members’ lives and on their families.

5.2. Implications for Refugee Support

This study delved into the fundamental components and intricacies of how the participating networks function, as well as offering insight into members’ experiences of these structures. Specifically, our findings can offer practical information to those wishing to offer similar support to refugee women. In general, these findings can offer practical information to refugees wishing to be their own ‘first responders’ during their process of ‘belonging’ in Ireland, since this research has evidenced that grassroots women’s networks were more likely to facilitate cohesion.

Bolstering mental health was a key motivating factor for many of the participants to join their networks. And many women affirmed the success of their membership in making sense of their experiences of displacement, building personal resilience, and beginning the process of building a new life in Ireland. However, participants from three out of four networks argued a need for more specialised support to deal with traumatic experiences, and two networks expressed ambitions to provide an environment within their networks to do this.

For such a service to succeed, it would require support from bodies which can provide funding advice, assist capacity building, and offer development support. These bodies do exist, such as the Northern Ireland Council for Voluntary Action, Social Enterprise Republic of Ireland, and Volunteer Ireland. These organisations are non-governmental rather than state entities, though each receives some level of public funding to support their activities. As

Crisp (

2018) argues, humanitarian advocates must remain realistic about the limits of political support for refugee-focused provision and tailor their approaches accordingly. Further research is required to understand exactly how network funding mechanisms operate, barriers to gaining specialised support, and availing of funding opportunities, especially for grassroots networks.