Beyond Borders: Unpacking the Key Cultural Factors Shaping Adaptation and Belonging Abroad

Abstract

1. Conceptual Frameworks

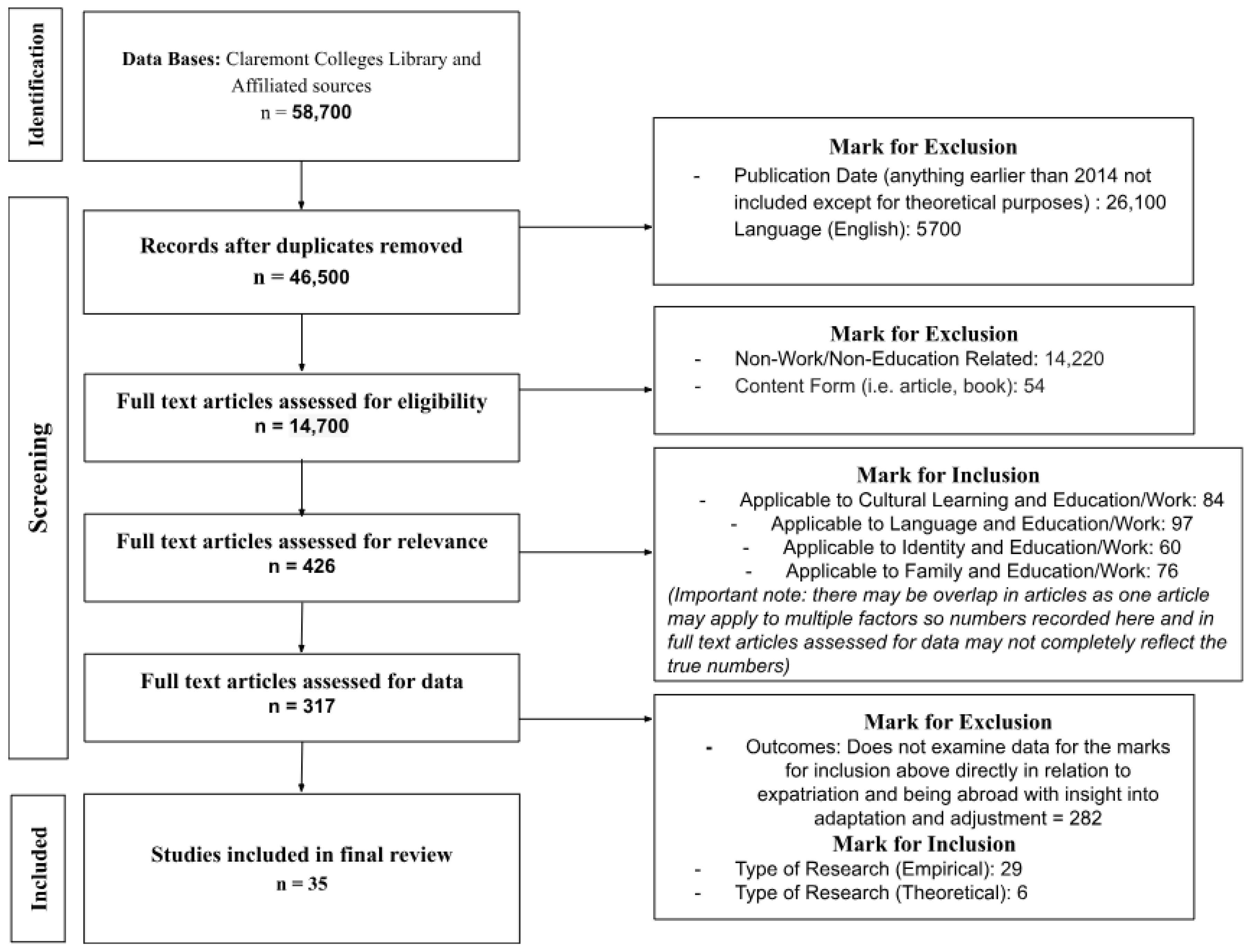

2. Methods

3. Results

Demographic Trends of Expatriate Literature

4. Discussion

4.1. Theme 1: Language Proficiency and Social Acceptance

4.2. Theme 2: Cultural Intelligence (CQ) and Social Networks

4.3. Theme 3: Identity Integration and Belongingness

4.4. Theme 4: Family Status and Systemic Support

5. Future Research and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abbas, Asad, Kenneth K. Sunguh, Arturo Arrona-Palacios, and Samira Hosseini. 2021. Can we have trust in host government? Self-esteem, work attitudes and prejudice of low-status expatriates living in China. Economics and Sociology 14: 11–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Nahyan, Sheikha S. K. A. N., and Laura L. Matherly. 2017. An empirical test of the predictors of national-expatriate knowledge transfer and the development of sustainable human capital. In Strategies of Knowledge Transfer for Economic Diversification in the Arab States of the Gulf. Edited by Rasmus Gjedssø Bertelsen, Neema Noori and Jean-Marc Rickli. Berlin: Gerlach Press, pp. 203–21. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, Kelly-Ann, Margaret L. Kern, Christopher S. Rozek, Dennis M. McInerney, and George M. Slavich. 2021. Belonging: A review of conceptual issues, an integrative framework, and directions for future research. Australian Journal of Psychology 73: 71–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Tamimi, Nouf N., and Shifan T. Abdullateef. 2023. Towards smooth transition: Enhancing participation of expatriates in academic context. Cogent Social Sciences 9: 2185986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, Njal. 2021. Mapping the expatriate literature: A bibliometric review of the field from 1998 to 2017 and identification of current research fronts. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 32: 4687–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, Soon, Linn Van Dyne, Christine Koh, K. Y. Ng, Klaus J. Templer, Cheryl Tay, and N. Anand Chandrasekar. 2007. Cultural intelligence: Its measurement and effects on cultural judgment and decision making, cultural adaptation and task performance. Management and Organization Review 3: 335–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baluku, Martin M., Steffen E. Schummer, Dorothee Löser, and Kathleen Otto. 2019. The role of selection and socialization processes in career mobility: Explaining expatriation and entrepreneurial intentions. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance 19: 313–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, Albert. 1977. Social Learning Theory. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister, Roy F., and Mark R. Leary. 1995. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin 117: 497–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayraktar, Secil. 2019. A diary study of expatriate adjustment: Collaborative mechanisms of social support. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management 19: 47–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biemann, Torsten, and Maike Andresen. 2010. Self-initiated foreign expatriates versus assigned expatriates: Two distinct types of international careers? Journal of Managerial Psychology 25: 430–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Jiexiu, and Junwen Zhu. 2020. Cross-Cultural Adaptation Experiences of International Scholars in Shanghai: From the Perspective of Organisational Culture. Singapore: Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabic, Marina, Miguel González-Loureiro, and Michael Harvey. 2015. Evolving research on expatriates: What is ‘known’ after four decades (1970–2012). The International Journal of Human Resource Management 26: 316–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, Laura P. 2018. An expatriate’s first 100 days: What went wrong? Management Teaching Review 3: 309–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engle, Allen D., Zsuzsanna Szeiner, Sylvia Molnár, and Jozsef Poór. 2024. Key factors of corporate expatriates’ cross-cultural adjustment—An empirical study. Central European Business Review 13: 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faeth, Pia C., and Markus G. Kittler. 2020. Expatriate management in hostile environments from a multi-stakeholder perspective—A systematic review. Journal of Global Mobility 8: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, Ding. 2023. Chinese in Africa: Expatriation regime and lived experience. Journal of Ethnic Migration Studies 49: 2720–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenech, Roberta, Priya Baguant, and Ihab Abdelwahed. 2020. Cultural learning in the adjustment process of academic expatriates. Cogent Education 7: 1830924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichtnerová, Eva, and Robert J. Nathan. 2023. The role of local language mastery for foreign talent management at higher education institutions: Case study in Czechia. European Journal of Management Issues 31: 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipič Sterle, Mojca, Johnny R. J. Fontaine, Jan De Mol, and Lesley L. Verhofstadt. 2018. Expatriate family adjustment: An overview of empirical evidence on challenges and resources. Frontiers in Psychology 9: 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischmann, Carolin, Laura-Christiane Folter, and Jolanta Aritz. 2020. The impact of perceived foreign language proficiency on hybrid team culture. International Journal of Business Communication 57: 497–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goede, Julia, and Dirk Holtbrügge. 2021. Methodological issues in family expatriation studies and future directions. International Studies of Management & Organization 51: 95–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Yang F., Xuesong A. Gao, Michael Li, and Chun Lai. 2021. Cultural adaptation challenges and strategies during study abroad: New Zealand students in China. Language, Culture and Curriculum 34: 417–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habti, Driss, and Maria Elo, eds. 2019. Global Mobility of Highly Skilled People: Multidisciplinary Perspectives on Self-Initiated Expatriation. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagerty, Bonnie M. K., Judith Lynch-Sauer, Kathleen L. Patusky, Maria Bouwsema, and Peggy Collier. 1992. Sense of belonging: A vital mental health concept. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing 6: 172–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Yu, Greg J. Sears, Wendy A. Darr, and Yu Wang. 2022. Facilitating cross-cultural adaptation: A meta-analytic review of dispositional predictors of expatriate adjustment. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 53: 1054–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haour-Knipe, Mary. 2001. Moving Families: Expatriation, Stress and Coping, 1st ed. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslberger, Arno, Chris Brewster, and Thomas Hippler. 2013. The dimensions of expatriate adjustment. Human Resource Management 52: 333–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofhuis, Joep, Katja Hanke, and Tessa Rutten. 2019. Social networking sites and acculturation of international sojourners in the Netherlands. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 69: 120–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ipek, Ebru, and Philipp Paulus. 2021. The influence of personality on individuals’ expatriation willingness in the context of safe and dangerous environments. Journal of Global Mobility: The Home of Expatriate Management Research 9: 264–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Young Y. 2015. Finding a “home” beyond culture: The emergence of intercultural personhood in the globalizing world. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 46: 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, David A. 1984. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Saddle River: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Lapointe, Émilie, Christian Vandenberghe, and Shea X. Fan. 2022. Psychological contract breach and organizational cynicism and commitment among self-initiated expatriates vs. host country nationals in the Chinese and Malaysian transnational education sector. Asia Pacific Journal of Management 39: 319–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levett-Jones, Tracy, and Judith Lathlean. 2009. The ascent to competence conceptual framework: An outcome of a study of belongingness. Journal of Clinical Nursing 18: 2870–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder, Christian. 2019. Expatriates’ motivations for going abroad: The role of organisational embeddedness for career satisfaction and job effort. Employee Relations 41: 544–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Ching-Hsiang, and Hung-Wen Lee. 2008. A proposed model of expatriates in multinational corporations. Cross Cultural Management: An International Journal 15: 176–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maertz, Carl P., Riki Takeuchi, and Jieying Chen. 2016. An episodic framework of outgroup interaction processing: Integration and redirection for the expatriate adjustment research. Psychological Bulletin 142: 623–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Jina, and Yan Shen. 2015. Cultural identity change in expatriates: A social network perspective. Human Relations 68: 1533–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Yusuf, Bibi N., Norhayati Zakaria, and Asmat-Nizam Abdul-Talib. 2021. Using social network tools to facilitate cultural adjustment of self-initiated Malaysian female expatriate nurses in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Infection and Public Health 14: 380–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumtaz, Sana, and Sadia Nadeem. 2023. Understanding the development of a common social identity between expatriates and host country nationals. Personnel Review 52: 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, Angie M. G. 1978. Unity versus diversity. Zygon: Journal of Religion and Science 13: 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachmayer, Ara, and Kathleen Andereck. 2019. Enlightened travelers? Cultural attitudes, competencies, and study abroad. Tourism, Culture & Communication 19: 165–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazil, Nur Hafeeza A., Intan H. Mohd Hashim, Julia A. Aziya, and Nur Farah W. Mohd Nasir. 2023. International students’ experiences of living temporarily abroad: Sense of belonging toward community well-being. Asian Social Work and Policy Review 17: 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekerti, Andre A., Quan H. Vuong, and Nancy K. Napier. 2017. Double-edge experiences of expatriate acculturation: Navigating through personal multiculturalism. Journal of Global Mobility 5: 225–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamin, Xavier. 2021. Specific work-life issues of single and childless female expatriates: An exploratory study in the Swiss context. Journal of Global Mobility 9: 166–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, Dhara, Narendra M. Agrawal, and Miriam Moeller. 2019. Career decisions of married Indian IT female expatriates. Journal of Global Mobility 7: 395–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunguh, Kenneth K., Asad Abbas, Alabi C. Olabode, and Zhang Xuehe. 2019. Do identity and status matter? A social identity theory perspective on the adaptability of low-status expatriates. Journal of Public Affairs 19: e1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaak, Reyer A. 1995. Expatriate failures: Too many, too much cost, too little planning. Compensation & Benefits Review 27: 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Zee, Karen, and Jan P. Van Oudenhoven. 2022. Towards a dynamic approach to acculturation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 88: 119–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vihari, Nitin S., Jesu Santiago, Mohit Yadav, and Anugamini P. Srivastava. 2024. Role of intraorganizational social capital and perceived organizational support on expatriate job performance: Empirical evidence. Industrial and Commercial Training 56: 311–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vulchanov, Ivan O. 2020. An outline for an integrated language-sensitive approach to global work and mobility: Cross-fertilising expatriate and international business and management research. Journal of Global Mobility: The Home of Expatriate Management Research 8: 325–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, Gregory M., Mary C. Murphy, Christine Logel, David S. Yeager, J. P. Goyer, Shannon T. Brady, Katherine T. U. Emerson, David Paunesku, Omid Fotuhi, Alison Blodorn, and et al. 2023. Where and with whom does a brief social-belonging intervention promote progress in college? Science 380: 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, Melissa, and Christopher S. Dutt. 2022. Expatriate adjustment in hotels in Dubai, UAE. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism 21: 463–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurtz, Olivier. 2022. A transactional stress and coping perspective on expatriation: New insights on the roles of age, gender and expatriate type. Journal of Global Mobility: The Home of Expatriate Management Research 10: 351–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Ling E., Anne-Wil Harzing, and Shea X. Fan. 2018. Managing Expatriates in China: A Language and Identity Perspective. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Citation | Title | Journal | Methodology | Samples | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fleischmann et al. (2020) | The Impact of Perceived Language Proficiency on Hybrid Culture | International Journal of Business Communication | Online Survey + Semi-Structured Interviews | 103 Corporate Individuals (79 Indian, 22 German, 1 Kenyan, 1 Japanese) | Language proficiency in team language leads to positive team culture. |

| Bayraktar (2019) | A Diary Study of Expatriate Adjustment: Collaborative mechanisms of social support | International Journal of Cross Cultural Management | Diary-Study | Single (spousal status) expatriates sent on temporary international assignments—42 individuals (26 men & 16 women) | Different networks provide different social support; therefore, expatriates with diverse social networks in their host and home country have access to more support facilitating adjustment. |

| Pazil et al. (2023) | International Students’ Experiences of Living Temporarily Abroad: Sense of Belonging Toward Community Well-Being | Asian Social Work and Policy Review | Qualitative—In-Depth Case Interviews and Thematic Analysis | 14 (7 male & 7 female) international postgraduate students (Bangladesh, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Indonesia, Pakistan, Jordan, Yemen, Algeria, Egypt) | Conational friends are avenues for social support and enhance belongingness. Face-to-face interactions prove to be more beneficial to facilitate connections than social media. |

| Gong et al. (2021) | Cultural Adaptation Challenges and Strategies During Study Abroad: New Zealand Student in China | Language, Culture, and Curriculum | Qualitative Analysis of Reflective Journals and Interviews (86 entries total) + Group Interviews | 15 New Zealand Student | Students faced language-based lifestyle, and academic challenges which they countered with cognitive, affective, and skill development in facilitating communication with the local people suggesting revisions to traditional pedagogical approaches. |

| Mohd Yusuf et al. (2021) | Using Social Network Tools to Facilitate Cultural Adjustment of Self-Initiated Malaysian Female Expatriate Nurses in Saudi Arabia | Journal of Infection and Public Health | Qualitative Study with Semi-Structured Interviews | 16 Malaysian Female Nurses Working in Saudi Arabia | Social network tools help reduce loneliness, culture shock, and emotional stress, thereby supporting adjustment to life and work |

| Hofhuis et al. (2019) | Social Network Sites (SNS) and Acculturation of International Sojourners in the Netherlands: The Mediating Role of Psychological Alienation and Online Social Support | International Journal of Intercultural Relations | Digital Survey with no compensation for participation | 126 short-term sojourners (64 international students & 62 workers) with no Dutch nationality (36 different countries of nationality) | Cultural maintenance and host country participation are positively related to well-being. On the other hand, SNS to the home country is related to online social support but also contributes to psychological alienation. |

| Wilson and Dutt (2022) | Expatriate Adjustment in Hotels in Dubai, UAE | Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism | Online Survey with 5-point scale for strongly agree to strongly disagree | 104 (47.12% male & 52.88% female between 25–34 years & 30 different nationalities) lower and middle-level managers (expatriates) working in luxury hotels in Dubai hospitality industry | Push factors are less important than expected while personal motivators are important for success. The social aspect was the least well-adjusted to. |

| Pachmayer and Andereck (2019) | Enlightened Travelers? Cultural Attitudes. Competencies & Study Abroad | Tourism Culture & Communication | Qualitative analysis through semi-structured interviews | 30 participants (8 males & 22 females) and 70% had prior foreign travel experience | Changes in cultural attitudes led to less stigma while increases to cultural competence led to adaptability, confidence and openness. |

| Dabic et al. (2015) | Evolving Research on Expatriates: What is “Known” After our Decades (1970–2012) | The International Journal of Human Resource Management | Bibliometric | 438 papers in 104 different journals by 233 authors | Research is currently centered around multinational US perspectives with converging empirical results on the expatriate cycle (selection, preparation, training & development repatriation). Research needs to be broadened in terms of geography and issues addressed (gaps in literature). |

| Linder (2019) | Expatriates’ Motivations for Going Abroad: The Role of Organisational Embeddedness for Career Satisfaction and Job Effort | Employee Relations | Online Survey & ANOVA PLS | 98 Managers 165 expatriates—self-initiated (66) and assigned (99) w/125 men & 44 women from 11 different countries | Positive relationship between the degree of organisational embeddedness in institutions abroad, job performance, and career satisfaction. Perceptions of embeddedness depended on workers’ mindsets around career ambitions. |

| Shah et al. (2019) | Career Decisions of Married Indian IT Female Expatriates | Journal of Global Mobility: The Home of Expatriate Management Research | Semi-structured Interviews | 24 married Indian IT women on international assignments post-marriage | Clarity, shared sense of purpose between spouses and extended family support network are major factors impacting married Indian IT females’ decision to take on international assignments. |

| Salamin (2021) | Specific Work-Life Issues of Single and Childless Female Expatriates: An Exploratory Study in the Swiss Context | Journal of Global Mobility: The Home of Expatriate Management Research | Semi-structured face-to-face interviews | 20 single, childless expatriates | Work-nonwork enrichment enables personal development. There is a lack of appreciation for female expatriates’ nonwork time, resulting from strong investment in the work sphere and flexibility to go abroad contributing to a work-nonwork conflict. This, alongside Switzerland’s traditional family and gender roles, led to exclusion from social networks. |

| Zhang et al. (2018) | Managing Expatriates in China: A Language and Identity Perspective | Palgrave Macmillan | 2-phase case study with semi-structured interviews | Nordic MNCs operating in China with local Chinese employees and Nordic expatriates | Locals perceived expatriates who were more skilled in the Chinese language or immersed in the language learning process as more approachable and respectful. On the other hand, those who relied on English were often excluded and were unable to form strong relationships/networks. |

| Mumtaz and Nadeem (2023) | Understanding the Development of a Common Social Identity Between Expatriates and Host Country Nationals | Personnel Review | Three-wave time-lag design—2 questionnaires + personal visits and emails | 93 Chinese and 239 Pakistani host country nationals in 55 organizations varying in 17 sectors of work | Trust development and intercultural communication were positively associated with the development of a common social identity between expatriates and HCNs. Interaction adjustment had a negative impact on a common social identity. |

| Habti and Elo (2019) | Global Mobility of Highly Skilled People: Multidisciplinary Perspectives on Self-Initiated Expatriation | Springer International Publishing | Case study + Questionnaire of 17 MCQ (1-totally agree, 5-totally disagree) & 3 SAQs | 236 individuals Group of randomly sampled line managers working in various fields. | SIEs were judged for how they act in the workplace (performance & cooperation) and feeling accepted was a challenge. Skills like flexibility, independent problem solving, and tolerance of difference were deemed significant indicators of functional social relationships in the work community. |

| Ipek and Paulus (2021) | The Influence of Personality on Individuals’ Expatriation Willingness in the Context of Safe and Dangerous Environments | Journal of Global Mobility: The Home of Expatriate Management research | Experimental vignette | 278 participants (students and employees) 41.3% female 49.28% in a committed relationship 68.71% had prior international experience 60.79% were students 39.21% were employed for wages 85.32% worked full-time 14.58% worked part-time | Expatriate selection needs to take personality (openness to experience, conscientiousness, emotionality) into consideration for expatriation management & training needs. |

| Al Nahyan and Matherly (2017) | An Empirical Test of the Predictors of National-Expatriate Knowledge Transfer and the Development of Sustainable Human Capital | Strategies of Knowledge Transfer for Economic Diversification in the Arab States of the Gulf | 100 Question Survey (Likert-Scale format) | 496 Surveys 62% male & 38% female 52% Home Country Nationals 19% Arab and Asian 8% Western | Knowledge transfer between nationals and non-nationals is important for knowledge building for non-national individuals. This process is strongly associated with trust, transparency, process improvement, and incentives. |

| Wurtz (2022) | A Transactional Stress and Coping Perspective on Expatriation: New Insights on the Roles of Age, Gender, and Expatriate Type | Journal of Global Mobility: The Home of Expatriate Management Research | Questionnaire (demographics + COPE Inventory- subscales) | 1269 expatriates from four MNCs with 448 survey responses | There are various methods of coping; however, there are significant differences between expatriate groups. Older vs. Younger: Older expatriates are more likely to use problem-focused coping strategies (active, coping, planning, restraint) and emotion-focused disengagement (substance use) Female vs. Male: Female expatriates are more likely to use acceptance, positive reinterpretation, and humor to cope. SIEs vs. AEs: SIEs are more likely to rely on emotional social support. |

| Fei (2023) | Chinese in Africa: Expatriations Regime and Lived Experience | Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies | Surveys to collect demographic & background data + Semi-structured interviews to note experiences and perceptions | 66 Chinese expatriates working in Ethiopia | Expatriation serves state-led developmental goals, allows Chinese workers to explore career/life goals, and Chinese companies’ global ventures, but also introduces different forms of inclusion and exclusion to society. |

| Vihari et al. (2024) | Role of Intraorganizational Social Capital and Perceived Organizational Support on Expatriate Job Performance Empirical Evidence | Industrial and Commercial Training | Survey using a 5-point Likert scale + Hypothesis testing using SEM with a two-stage approach | 268 expatriates in UAE | Intraorganizational social capital and perceived organizational support has a positive influence on expatriate job performance while Islamic work ethic mediates the relationship between all factors. |

| Engle et al. (2024) | Key Factors of Corporate Expatriates Cross-Cultural Adjustment | Central European Business Review | Questionnaire with 6-point Likert scale | 62 Japanese expatriates (senior execs with families) in Hungary with a typical posting of 4–6 years | Longer posting time resulted in increased expatriate openness while higher English language skills led to more willingness to integrate. |

| Chen and Zhu (2020) | Cross-Cultural Adaptation Experiences of International Scholars in Shanghai | Springer | Semi-structured interviews (Half were pre-prepared, the other half were based on participant responses) | 281 international scholars in Shanghai 77% joint venture schools 19% female 81% male 23% ordinary schools 7% female 93% male | Promising future/funding, international environment, and reputation of recruiting university influences expatriates’ decision to take academic positions in Shanghai. Additionally, regional factors and academic factors influenced cross-cultural adaptation with the differing organizational culture of the university and access to familial/social support. |

| Baluku et al. (2019) | The Role of Selection and Socialization Processes in Career Mobility: Explaining Expatriation and Entrepreneurial Intentions | International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance | Cross-sectional survey using online questionnaires | 544 German University students (61.2% female, ages 18–54, mean age 23.1) | Entrepreneurial and expatriate intentions are significantly associated with career orientation and field of study. Additionally, length of study was positively associated with expatriation intention, while negatively associated with entrepreneurial intention. |

| Lapointe et al. (2022) | Psychological Contract Breach and Organizational Cynicism and Commitment Among Self-Initiated Expatriates vs. Host Country Nationals in the Chinese and Malaysian Transnational Education Sector | Asia Pacific Journal of Management | One-year time-lagged study using surveys at 2 time points | 156 employees (SIEs and HCNs) from Chinese and Malaysian operations of a Western higher education institution | SIEs report more organizational cynicism than HCNs but less affective commitment, normative commitment, and continuance commitment. |

| Abbas et al. (2021) | Can We Have Trust in the Host Government? Self-Esteem, Work Attitudes, and Prejudice of Low-Status Expatriates Living in China | Economics and Sociology | Self-reported survey Analyzed with SEM and hierarchical regression | 366 foreign nationals (low-status expatriates) 192 (52.5%) males & 174 (47.5%) female 121 Black (33.1%), 188 (51.4%) Asian, 57 (15.5%) Arab Ages ranged 18–35 years with mean age between 31 and 35 | Trust in the host government increased job commitment and reduced turnover; however, pre-formed notions of prejudice negatively impacted expatriate development of trust. The relationship between this trust and work attitudes is moderated by self-esteem. |

| Fichtnerová and Nathan (2023) | The Role of Local Language Mastery for Foreign Talent Management at Higher Education Institutions: Case Study in Czechia | European Journal of Management Issues | 100 Question Survey | 211 foreign academics working in HEIs | Mastery of the Czech language positively influenced integration which contributed to the retention of foreign academics while also helping expatriate knowledge acquisition. |

| Sunguh et al. (2019) | Do Identity and Status Matter? A Social Identity Theory Perspective on the Adaptability of Low-Status Expatriates | Journal of Public Affairs | Hierarchical regression analysis | 366 expatriates working in China | High levels of perceived prejudices will negatively affect expatriates’ performance and social self-esteem. Age and level of education positively moderate the relationship between prejudice and self-esteem (i.e., higher education level lessens the negative effect of perceived prejudice on self-esteem. Host national support and self-cognition are also important for overall expatriate success. |

| Fenech et al. (2020) | Cultural Learning in the Adjustment Process of Academic Expatriates | Cogent Education | Online questionnaire using Likert scale + statistical analysis | 103 participants Ages ranging between 45 and 54 50.5% have 12+ years of experience 70% expatriates from a non-Arab culture (45%); have 12 years of experience or more (50.5%); and originate from a non-Arab culture (70%). | Cultural competence and adjustment have a positive relationship that increases with experience and age. Additionally, expatriates from different cultures tend to adjust better following the lines of the Supports the Cultural Distance Paradox. |

| Mao and Shen (2015) | Cultural Identity Change in Expatriates: A Social Network Perspective | Human Relations | Literature Review | N/A | Organizations can help facilitate opportunities for expatriates to build social networks which have a positive relationship to cultural intelligence. Alongside this, it is important to consider cross-culture relationship dynamics of expatriates’ social networks and their impact on expatriate cultural identity change. |

| Andersen (2021) | Mapping Expatriate Literature: A Bibliometric Review of the Field From 1998 to 2017 and Identification of Current Research Fonts | International Journal of Human Resource Management | Bibliometric Analysis | Global academic literature | Social capital and perceived social support are rising areas of interest within the field of research on expatriate management, role, and adaptation. Additionally, the key words “MNC,” “adjustment,” and “career,” are central to expatriate literature. |

| Maertz et al. (2016) | An Episodic Framework of Outgroup Interaction Processing: Integration and Redirection for Expatriate Adjustment Research | American Psychological Association | Literature review | Cross-cultural adjustment research from the 1960s to 2015 | Expatriate research has many variance-based models and lacks process-oriented research. Additionally, research has revealed that expatriates are motivated by three basic psychological needs: competence, belongingness, and autonomy from self-determination. |

| Faeth and Kittler (2020) | Expatriate Management in Hostile Environment from a Multi-Stakeholder Perspective: A Systematic Review | Journal of Global Mobility: The Home of Expatriate Management Research | Literature Review | Global academic literature | Hostile environment conditions, lack of organizational support, conflicting family and social networks, and expatriate stress/maladjustment are positively associated with expatriate adjustment failure, lack of well-being, and work performance. |

| Dwyer (2018) | An Expatriate’s First 100 Days: What Went Wrong? | Management Teaching Review | Pedagogical/Instructional Design | Target population of students | Cross-cultural learning is an increasingly important subject pertaining to expatriate adjustment. In this light, engaging individuals with material is more valuable than giving definitions. |

| Al-Tamimi and Abdullateef (2023) | Towards Smooth Transition Enhancing Participation of Expatriates in Academic Context | Cogent Social Sciences | Focus group interviews and thematic analysis | 18 female expatriate faculty members from 3 different colleges in Saudi Arabia | Expatriates face challenges in each phase of adaptation (separation, transition, and re-aggregation) which affects their participation and productivity. Family and organizational support are important in this adaptation process. |

| Filipič Sterle et al. (2018) | Expatriate Family Adjustment: An Overview of Empirical Evidence on Challenges and Resources | Frontiers in Psychology | Narrative review and synthesis of empirical quantitative and qualitative data | Expatriates, their partners, and children from English-speaking Western countries | Main challenges included cultural stress, isolation, identity issues for children, and career loss for partners. Strong family cohesion was a major resource along with organizational/social support. |

| Characteristic | Details |

|---|---|

| Gender Ratio (k = 12) | All Male: 0% |

| Majority Male: 33.33% | |

| Equal Male-Female: 8.33% | |

| Majority Female: 25.00% | |

| All Female: 33.33% | |

| Type of Expatriates | General Expatriates: 40% |

| International Students: 15% | |

| Self-Initiated Expatriates: 10% | |

| Expatriate Families/Partners: 10% | |

| Occupation-Specific Expatriates: 25% | |

| Sample Age (k = 14) | Range in Mean Ages (years): 20–55 |

| Mean Age and SD: 27.66 ± 6.82 | |

| Occupational Diversity (k = 36) | Yes: 30% |

| No: 70% | |

| Duration of Stay | Short-Term (<1 year): 20% |

| Medium-Term (1–5 years): 50% | |

| Long-Term (>5 years): 15% | |

| Unspecified: 15% | |

| Cultural Diversity (N = 36) | Yes: 72% |

| No: 28% |

| Factors Affecting Adjustment | Themes | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Language | The importance of linguistic readiness for expatriate training | Limited pre-departure training and low language proficiency caused task and social challenges, while early language development enhanced socialization, belonging, and workplace integration (Engle et al. 2024; Fichtnerová and Nathan 2023; Fenech et al. 2020; Zhang et al. 2018). |

| Cultural Intelligence | Expatriates with high CQ can quickly activate cultural learning upon arrival—such as engagement in local customs, norms, and values | Cultural intelligence and adjustment promote cultural learning, improving local perceptions and social network formation through alignment with organizational norms (Chen and Zhu 2020; Habti and Elo 2019; Fenech et al. 2020). |

| Identity Integration | Meaningful relationships and involvement with the local communities contribute to expatriates’ integration of multiple identities | Absence of personality-based pre-departure training increased psychological alienation, while incorporating traits like emotionality and openness earlier fostered trust, intercultural communication, and host participation—enhancing well-being and integration (Hofhuis et al. 2019; Ipek and Paulus 2021; Mumtaz and Nadeem 2023). |

| Family Status | Family adjustment cannot be overlooked from an emotional, logistical, and psychological perspective | Expatriation can strain family dynamics without a shared purpose, but support from extended family helps reassure children and stabilize relationships (Goede and Holtbrügge 2021; Habti and Elo 2019; Shah et al. 2019). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Murali, M.; Varuma, R.; Almeida, A.M.; Feitosa, J. Beyond Borders: Unpacking the Key Cultural Factors Shaping Adaptation and Belonging Abroad. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 667. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14110667

Murali M, Varuma R, Almeida AM, Feitosa J. Beyond Borders: Unpacking the Key Cultural Factors Shaping Adaptation and Belonging Abroad. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(11):667. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14110667

Chicago/Turabian StyleMurali, Mrdah, Roystone Varuma, Aaliyah Marie Almeida, and Jennifer Feitosa. 2025. "Beyond Borders: Unpacking the Key Cultural Factors Shaping Adaptation and Belonging Abroad" Social Sciences 14, no. 11: 667. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14110667

APA StyleMurali, M., Varuma, R., Almeida, A. M., & Feitosa, J. (2025). Beyond Borders: Unpacking the Key Cultural Factors Shaping Adaptation and Belonging Abroad. Social Sciences, 14(11), 667. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14110667