Abstract

This article investigates how populist leaders in power across Europe and the Americas responded to the COVID-19 pandemic, with a focus on the extent and form of medical populism—the calculated use of health crises to challenge establishment authority, mobilize support, and promote alternative governance. Drawing on speeches and public statements from a select group of populist heads of government—including Orbán, Matovič, Maduro, López Obrador, Bukele, Bolsonaro, and Trump—we compare cross-regional discursive patterns using a framework developed. Contrary to expectations of ideological or regional uniformity, we find that medical populism is a transnational and trans-ideological phenomenon. While expressions vary, all leaders engaged in anti-elitist, conspiratorial, or anti-scientific rhetoric. Centralized political authority and weak healthcare systems, rather than ideology, more reliably explain the intensity of medical populist discourse. These findings challenge the common belief in the literature that populist misinformation is mainly connected to the radical right or low institutional trust, and highlight instead the structural incentives that drive medical populism in times of crisis.

1. Introduction

How do populists in power respond to a national health crisis like a global COVID-19 pandemic in the Global South and North? Is there a uniform pattern or do populists vary in their approach by global region or specific context? After all, Taggart (2000, 2002) had suggested that populism always take on local hues. We also intend to focus on populists in government rather than in opposition where we may expect populists to be uniformly opposed to mainstream political actors and their policies. Thus, we ask: do populists in power engage in responsive or responsible politics?

Research on populism has often focused on the link between populism and crisis, as the idea of crisis has been a central theme for many populist leaders (Canovan 1999; Mouffe 1999; Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser 2012a, 2012b). According to Mény and Surel (2000, p. 181; see also Canovan 2005, pp. 81–82), populists promise to deliver “the people” from the crisis caused by elites.

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated a series of overlapping crises that provoked substantial challenges to governments worldwide. According to Weyland, populist politicians are known to be opportunistic and strategic (Weyland 2001) and not wedded to political dogmas; recent scholarship has argued that populists were able to exploit the pandemic. In doing so, they have portrayed governments as uncaring, overly expert-focused and bent on controlling people’s lives (Eberl et al. 2021). Indeed, research has shown significant declines in public trust in scientific, social, economic, political, and media institutions (Hamilton and Safford 2021; Rieger and Wang 2022).

From an oppositional logic, populism’s anti-establishment discourse and its “performance of crisis” (Moffitt 2016, p. 217) makes strategic sense. But what about populists in power? Do they simply move the goalposts by maintaining a sense of crisis, vowing to fight the enemies of the common people at home and abroad and spreading misinformation from the vantage position of government, or do they generally act more like other governments, relying on conventional medical expertise and sound scientific practice?1 Another important consideration is that medical practices vary from country to country due to different cultural conditions and disparities in healthcare access and availability. As a result, populist responses to public health crises are likely to differ between developing and developed countries, where public health systems and alternative medical epistemologies adhere to distinct standards. This paper examines populist leaders in power across Europe and the Americas, two regions with contrasting traditions and recent trajectories of political populism, to assess how contextual differences shape their responses to the COVID-19 pandemic.

To address the conceptual vagueness and the lack of comparative regional research on populists in power, our study proceeds from a twofold question: (a) What differences, if any, do we observe in the discourse on COVID-19 between populists in power in Europe and the Americas? (b) Have populist heads of government engaged in radical populist discourse as an alternative form to mainstream COVID mitigation strategies?

To avoid the risk of getting lost in differences between discursive practices and local ideas about governance and health policy in a cross-country and cross-regional comparison, we adopt a consistent analytical framework developed by Lasco and Curato (2019): the concept of “medical populism” provides a novel analytical framework for studying and examining how populist leaders instrumentalize health crises. We do this by measuring systematically how medicine and health policy are politicized and instrumentalized to express distrust in the establishment, mobilize constituencies, and promote alternative governance models. As will be discussed in detail below, this concept offers an operationalizable framework for measuring populist discursive strategies in public health.

To assess the extent to which populists in power resort to medical populism, we have conducted a comprehensive analysis of speeches made by populist leaders in public office in the Americas and Europe, in which they explain their responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. These regions, including North America with the United States, were selected because they have been central to the resurgence of populism in recent decades (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser 2012a). In a seminal article, Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser (2012b) also point out that when populists in government are compared in Europe and Latin America, the comparison is often between exclusionary populists (radical right populists) in Europe and inclusionary populists (leftist populists) in Latin America.

We examine and compare cross-regionally how populist leaders there use medical ideas to support policies to mitigate the spread of the virus. The cases selected capture both intraregional and interregional variation. They are very limited in number as there were only few populist leaders in power during this period. In Europe, the study includes Viktor Orbán (Hungary) and Igor Matovič (Slovakia), and in the Americas, Nicolás Maduro (Venezuela), Andrés Manuel López Obrador (also known as AMLO, Mexico), Nayib Bukele (El Salvador), Jair Bolsonaro (Brazil), and Donald Trump (United States). These cases can be considered examples of dominant manifestations of populism in their respective contexts (Gerring 2007, p. 91), which provides a solid basis for comparative analysis. By examining their pandemic responses along five causal dimensions—populism–medical discourse nexus, ideological orientation, use of traditional/alternative medicine, national health infrastructure, and power centralization—the findings reveal that medical populism is a common rhetorical tool among populists in power, irrespective of region or ideological orientation: all leaders engaged in some degree of anti-elitist, conspiratorial, or anti-scientific discourse, despite the fact that medical populist discourses differ. Contrary to initial expectations, our analysis shows that ideology is a weak predictor of medical populism: political power centralization and limitations of healthcare systems offer a more consistent explanation. Notably, leaders with higher executive authority, such as Maduro, Bukele, and AMLO, exhibited more frequent use of medical populism, indicating that power consolidation does not diminish but may incentivize the use of anti-mainstream medical narratives. Although Latin American leaders were more likely to invoke traditional or folk remedies, the promotion of pseudoscientific cures and conspiracy theories was not regionally bound. These findings challenge the common belief in the political science literature that populist misinformation is mainly connected to the radical right or low institutional trust. Our cross-regional analysis shows that medical populism is a trans-ideological and transnational phenomenon shaped by the following structural conditions: healthcare capacity and centralization of institutional power.

This article begins by explaining our theoretical approach, then followed by our methodological approach and empirical strategy. The second part is where we present our analysis, by discussing the findings and their implications.

2. Our Theoretical Approach

A comparison across three global regions—each of which has experienced populism as a major force shaping politics in general and democracy in particular—necessarily requires the adoption of a minimal definition and an allowance for contextual variation. In Latin America, populism developed within the framework of developmental politics and sought to forge cross-class coalitions (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser 2012b, pp. 3–5). Western Europe, by contrast, experienced the rise of populist parties through a different trajectory, with movements initially emerging as protests and outsider formations challenging entrenched party systems and insider politics. In the United States, populism first appeared in the context of modernization and industrialization, giving voice to groups who felt threatened by both corporate capitalism and an increasingly organized working class.

Taking these contextual differences into account, we understand populism fundamentally as a form of moral politics structured around a core antagonism between two ostensibly homogeneous yet ambiguously defined collectives—the common people and the corrupt elites (cf. Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser 2012a, pp. 8–9; Heinisch and Mazzoleni 2021, pp. 123–25). Both of these categories can be regarded, to some extent, as empty signifiers (Laclau 1977). Following Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser’s (2012b) approach, we therefore employ a minimal definition of populism as our conceptual foundation.

For the purposes of this analysis, it is less relevant whether populism is conceived ideationally—that is, as reflecting the genuine beliefs of political leaders—or as a rhetorical strategy expressed through claims and framing devices. Since we can only measure discourse, we treat populism here as a set of claims articulated to frame political communication in a particular way.

As already mentioned, most scholars consider populism as being built around claims about the antagonism between self-serving elites and common people whose true interests are betrayed by those entrusted to represent them (Caramani 2017). This systematic failure of representation (Bardi et al. 2014; Saward 2010) is the moral foundation of the populists’ call for action promoting radical change. Populist narratives typically involve the construction of a category of people deserving of saving (in-group) and categories of enemies who pose a threat (out-groups). Both groups are abstractions of the conceptions which may be subject to change depending on context and political circumstances.

During the pandemic, populists around the world are claimed to have politicized the crisis in different ways (e.g., Gugushvili et al. 2020; Hallin et al. 2024; Oliveira et al. 2021; Ringe and Rennó 2022; Touchton et al. 2023). The “foreign” dimension of COVID-19 underscored not only the virus’s origin abroad—specifically in China—and emerging nationalism (Singh 2022) but also exposed the broader challenges of global governance. The crisis highlighted national vulnerabilities and interdependencies intensified by globalization (McNamara and Newman 2020) and the limitations of multilateralism (Fazal 2020). For populists in power, this context imposed unique constraints not faced by their opposition counterparts, who do not bear the burden of governance or the consequences of their policy choices.

We examine populist responses to COVID-19 along two key dimensions. First, how populists in power adapt to crisis in relation to left–right ideology (Filc 2015; Font et al. 2021), particularly through inclusionary or exclusionary forms that influence populist governments’ approaches to out-groups, such as marginalized groups and minorities. Second, the extent to which populists in power adopt a confrontational stance toward established authorities and experts, reflecting a broader distrust of official information and “objective” facts disseminated by the mainstream (Casarões and De Magalhães 2021; Devine et al. 2020). This distrust enables the substitution of expert consensus with “alternative truths,” including non-standard treatments, miracle cures, or traditional remedies.

2.1. Crisis Discourse of Populists in Power

The present article follows a broadly accepted definition of populism as a political discourse and performance that frames politics as a moral struggle between a virtuous and homogeneous “people” and corrupt or self-serving “elites” (Moffitt 2016; Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser 2012a, 2012b) and collective action frames: following Aslanidis (2016), we understand populism as a discourse which mobilizes constituencies.

Building on Moffitt’s later synthesis (Moffitt 2020), populism is understood less as a fixed ideology than as a performative logic of representation that privileges authenticity, crisis performance, and the claim to speak for “the people.” This conceptualization helps explain why leaders as ideologically diverse as Orbán, López Obrador, and Bolsonaro can all be categorized as populists, even if differing in content and ideology: they share the same antagonistic master frame, the antagonism between two homogeneous groups (the people and the elites) and, given the context of the pandemic, the performance of crisis as an internal core feature. Accordingly, the causal dimensions we outline below (anti-elitism, conspiracy framing, alternative epistemologies, etc.) derive from this core logic of populist performance rather than from partisan ideology. Our focus on populist leaders in power thus highlights how the performative and moral claims that constitute populism adapt once populists control state institutions and face the practical constraints of governance.

The idea of crisis is necessary to justify the call for radical change. It serves to motivate people who might otherwise be fearful of change in a rapidly changing world where they seek familiarity and comfort (Heinisch and Koxha 2023, pp. 123–24). Only when the status quo is intolerable does change become an absolute necessity. In this view, crises are primarily mediated and communicated, and thus “framed and dramatized by political actors” (Moffitt 2015; 2016, p. 190). Populists are therefore particularly adept at mobilizing ‘the people’ against a threatening enemy, simplifying complex issues, and calling for decisive action to prevent or resolve the crisis. As large segments of society come to believe that the political system is failing them, they seek radical alternatives to the status quo, which in turn creates opportunities for new political actors to push alternative truths and sow distrust of established scientific authority (see Brubaker 2021; Dietz 2013). Consequently, we would expect populists to deliberately exacerbate and exploit a major health crisis to undermine rival authority and trust in elites and established institutions.

However, as Brubaker (2021) notes, the pandemic highlighted several paradoxes of populism: populists depend on crises to sustain their legitimacy, yet exacerbating the perception of crisis might backfire against them if the anti-expertise and anti-state rhetoric, minimalization, dramatization or disinformation spiral out of control. It is still unclear how populists react when they themselves are in power. Another strategy may thus be to appeal to national unity and shift the enemy or scapegoat from domestic elites to foreign elites (Heinisch and Koxha 2023, pp. 114–35).

Another discursive response is the reframing of the crisis in terms of juxtaposing the need for strong domestic leadership with the alleged incompetence of foreign actors and supposed institutional deficits of entities like the EU or the WHO. A third approach may have been to identify domestic opposition and critics of government policies as undermining national solidarity and playing into the hands of foreign enemies. A fourth strategy may involve making common sense appeals thereby masking the policy role of experts.

2.2. Medical Populism as a Means of Evaluating Populist COVID Discourses

To assess the discourse of populists in power, we turn to the concept of medical populism, which allows us to trace truth claims and the promotion of alternative medical procedures and policies in Europe and the Americas (Lasco and Curato 2019). This concept is embedded in the broader and more fundamental concept of “epistemological populism” (Saurette and Gunster 2011). Specifically, medical populism proposes an alternative way of arriving at truths or truth claims centered on common people (see Adler and Drieschova 2021; Van Zoonen 2012; Ylä-Anttila 2018). Epistemological populism promotes alternative sciences and other unconventional, non-approved and unconventional medicines. We refer to this in this text as “miracle cures”. “Alternative lab” solutions refer to non-approved chemical substances and should be distinguished from alternative medicine, traditional folk remedies, as well as esoteric and spiritual claims2.

Designed to capture populist responses to and constructions of health crises that pit the people against the establishment, and building on the work of Lasco (2020), medical populism is consistent with other forms of populism. It is neither an entirely new idea nor a fundamentally different phenomenon (Mede et al. 2020). Rather, we regard it as a sub-form of political populism by representing a type of framing that actors employ for political purposes. Medical populism therefore perceives a conflict between the knowledge, beliefs, and practices of ordinary people regarding disease and healing, on the one hand, and the opinions and actions of experts and elites on the other. It is comprised of four core elements: (a) Simplifying and downplaying the pandemic, (b) dramatization of the crisis and governments’ responses to it; (c) forging of divisions (anti-elitism) and exclusionary forms of populism, and (d) the invocation of alternative, unconventional, false, misleading, unfounded and/or unproven medical issues and treatments.

2.3. Conceptualizing Populist Discursive Framing in a Medical Crisis

Since political discourses are not static, they follow a script or scenario in which the discursive framing is adapted to changing circumstances and emerging functional needs. This means that there are different stages in the development of a discourse that provide points of comparison. These stages serve their own functional logic and thus also affect how something is expressed. Therefore, we not only compare discourses as a whole, but, following Snow and Benford (1988), divide the discourses into different functional segments that allow us to draw parallels between cases. The most important of these is diagnostic framing, which tells us what is wrong and who is to blame, prognostic framing, which warns us of the dire consequences of the diagnosis, and motivational framing, which tells us what populists want to happen.

Populist diagnostic framing identifies the populist antagonism, the Manichean oppositions between ‘the (virtuous) people’ whose interests are betrayed and who are in need of saving, and their ‘vertical’ enemies, the ‘elites’, an amorphous but variable group that typically includes politicians, public officials, economic and cultural elites, various types of experts, and others. Diagnostic framing can also point to ‘enemies’ along a horizontal axis in the form of ‘dangerous’ or undesirable outgroups such as minorities and immigrants. In opposition, populists characterize those in power as the natural antagonists of “the people” and blame them for the latter’s misfortunes. When populists themselves are in power, the diagnostic framing becomes more complex. In this scenario, the people are threatened by either another elite or an external threat from which the people must be protected. Thus, we would expect appeals to unity and scapegoating of critics as ruthless agents of outside interests or intent on undermining national solidarity.

While populist diagnostic framing establishes the initial condition, prognostic framing addresses the consequences that will result if the condition is left untreated. In opposition, populists construct crisis narratives that provide the justification for urgent and radical change. In government, populists would pursue a different prognostic framing by downplaying existing problems, shifting the blame elsewhere, or drawing attention to themselves as exceptional leaders or national saviors. They might invoke alternative crisis scenarios such as conspiracies, to counteract the influence of rival elites, such as experts or other political leaders.

In motivational framing, populists in opposition present themselves as change agents capable of saving the people. In government, however, populists would emphasize change but rather call for extraordinary measures to protect the people and prevent rival elites from implementing their own designs.

These frames not only allow us to standardize, compare, and thus analyze the populist framing, but also draw attention to the substantive aspect of populist rhetoric such as radical language, demagoguery, hyperbole, and strategic ambivalence (Laclau 2005; Heinisch et al. 2020).

3. Hypotheses

Based on the above discussion, we now formulate our hypotheses, with a conceptualization provided below each of them.

Hypothesis 1a.

The more populists in power engage in populist discourse, the more they spread medical misinformation.

Hypothesis 1a posits that higher levels of populist polarization operationalized as the intensity of in-group/out-group populist rhetoric, are positively associated with the dissemination of medical misinformation and conspiracy theories, as defined by Keeley (1999, p. 116) and Bergmann (2018). Thus, we expect that the level of dissemination of misinformation and disinformation, alternative truths, and alternative medicine is driven by the need of populist leaders to radicalize the discourse and create divisions as a means of increasing in-group support (e.g., Górka 2021; Rinaldi and Bekker 2020; Van Prooijen and Douglas 2017; Wintterlin et al. 2023).

Building on H1a, Hypothesis 1b posits that radical right populism, being inherently exclusionary, is more likely to employ polarizing strategies and discourse than leftist or inclusionary populism (McKee et al. 2020; Törnberg and Chueri 2025). As Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser (2012a) argue, drawing on extensive prior research, populism combines both inclusive and exclusive elements, though their balance varies by region. In Europe, populism is predominantly exclusionary, whereas in Latin America it tends to be inclusive. These differences depend on how populist actors define “the people” in opposition to “the elite” and on the ideological features shaping their movements. Despite these variations, both forms of populism challenge liberal democracy and seek to repoliticize issues neglected by the establishment. Extending this rationale, we propose that radical right populists pursue an exclusionary, and therefore more polarizing, discursive strategy than their leftist or inclusionary counterparts.

Hypothesis 1b.

Radical (exclusionary) right populists in power are more likely to spread medical misinformation than radical left (inclusionary) populists.

We also propose that the level of medical populism varies across regions and settings. First, we must consider that cultural traditions matter when it comes to alternative health care in the form of traditional medicines and folk remedies. These are deeply rooted in Latin American history and unlike in Europe, where complementary medicine is regulated and integrated into conventional health care (Kemppainen et al. 2018), Latin American populists may frame alternative medicine as a response to systemic failures and an expression of cultural sovereignty (see Hartmann 2016).

Hypothesis 2a.

Populists in office are more likely to engage in medical populism in Latin America because traditional or alternative forms of medicine are more culturally accepted.

In addition, the development of the health sector and the access to health care varies across countries in terms of its availability, especially for vulnerable populations and the informal sector. We expect this to be reflected in the political discourse of populist leaders in government. Inadequate conventional healthcare may motivate populists in public office to use medical populism to exploit public frustrations with such institutions by advocating alternative solutions (Bordignon 2023). This leads us to formulate the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2b.

Populists in office are more likely to engage in medical populism when the health infrastructure is poor and thus access to conventional healthcare severely restricted.

Finally, we propose that populist leaders who have consolidated their power are less likely to disseminate medical populist misinformation and disinformation. This is due to two key reasons: First, in a strong position, populists may see less need to engage in polarizing discourse that promotes unreliable panaceas to establish their dominance. Instead, they present themselves as national saviors and unifiers, leading to a reduction in polarizing rhetoric. Second, having already secured their authority, they are less likely to perceive rival power centers as threats and, therefore, feel less compelled to challenge scientific experts and health professionals.

Hypothesis 3.

Populists in office who have consolidated their power are less likely to engage in medical populism.

4. Methodological Approach and Empirical Strategy

We employ the representative claims analysis proposed by De Wilde et al. (2014) to examine, measure, and interpret communicative actions (“claims”) of populist actors, using MAXQDA24 to analyze public speeches. The advantage of this method is the use of flexible definitions of frames as units of measurement, which can vary from a sentence to an entire paragraph. This is particularly useful in our dataset, which, unlike technical policy documents or vague social media content, is based on speeches that strike a balance between policy relevance and substantive detail. In total, the analysis includes three speeches per actor, each exceeding 2000 words and ranging up to 11,000 words. The transcripts of public speeches as our primary data sources encompasses a variety of formats such as campaign speeches and interviews. Since speeches are analyzed as to how medical populism is used by populists in power, the coding aims to detect and identify rather than to quantify. Thus, even the low frequencies indicate a medical populist stance. Since a qualitative content analysis aims at identifying the presence and nature of features, the total amount of text is less relevant. Instead, it enables us to examine the argumentation, justification, and ideological content. Selecting smaller samples for studying populist discourse is a well-established method (see Hawkins 2010; Heinisch et al. 2024). Since the aim is not to track longitudinal pandemic responses but to explore how medical populism is constructed, this sample size should suffice, especially given the variety of cases in our qualitative analysis. The time frame, spanning 2020 to 2023, captures different stages of the pandemic.

Our codebook is designed to indicate whether a populist actor is ambivalent or has the intention to politicize public health through the promotion of certain miracle cures. As shown in Table S1 in the Supplementary Materials, being classified as “medical populism,” requires that the framing references to alternative medical knowledge claims propagating medical misinformation, pseudoscience, or alternative science3. Our approach combines inductive and deductive coding of speeches (Kuckartz and Rädiker 2019; Saldaña 2016) and extensive reliability tests (96.91% using ReCal2 according to Freelon 2013), the details of which we present in the Supplementary Materials. Deductive reasoning guided the core categories from the medical populism framework, while inductive reasoning captured unanticipated themes, such as references to religion, patriotism, or emotional appeals shaping the relation between the people, elites, out-groups and experts. This iterative approach kept the codebook grounded yet responsive to emerging patterns. Given the substantial qualitative dataset collected, we combine computer-based automation (automated lexical coding) and manual content analysis (see Rooduijn and Pauwels 2011, p. 1275) to manually verify and make sure to capture all medical populist frames. This approach also avoids overinterpreting claims. The indicators for discursive components of medical populism, i.e., diagnostic, prognostic, and motivational framing are also presented in detail in the Supplementary Materials.

Since our aim is to identify recurring patterns across discourses rather than infer causal relationships, we formulate hypotheses to guide our analysis. Thus, these hypotheses serve as heuristic propositions rather than as objects of statistical testing. As our aim is to identify recurring patterns across discourses rather than infer causal relationships, we formulate hypotheses to guide our analysis. Thus, these hypotheses serve as heuristic propositions rather than as objects of statistical testing.

5. Case Selection

Our analysis focuses on leaders rather than parties or programs, as populist movements in Europe and the Americas are largely leader-centric, and crises like COVID-19 further amplified leaders’ authority. While we acknowledge that cross-regional comparisons always pose challenges in terms of comparative equivalents, different contexts and histories, as well as conceptualizations (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser 2012a, 2012b). This is especially true for Europe, the United States, and Latin America with their somewhat different perceptions of populism and distinct scholarly traditions. In contrast, in Western Europe, populist parties arose through a different process—initially as protest movements and outsider formations opposing entrenched party systems and insider politics. In the United States, populism first appeared amid modernization and industrialization, representing groups who felt threatened by both corporate capitalism and an increasingly organized working class.

Given these differences and as already mentioned, we generally adopt the view that populism is, at its core, a form of moral politics characterized by a fundamental antagonism between two homogeneous yet ambiguously defined groups—the virtuous people and the corrupt elites.

Rather than selecting cases ourselves—and thus potentially contending with disagreements between country specialists and broad comparativists—we take advantage of datasets that have not only been validated (delete: Rooduijn et al. 2023; Meijers and Zaslove 2021) but are also widely used in the literature. For the European cases, we rely on the Popu.List (Rooduijn et al. 2023) to identify populist actors, while for the Americas we draw on the Global Populism Database (GPD) (Hawkins et al. 2019). Despite certain limitations, the cases identified through these sources provide a solid foundation for generating valid cross-regional and cross-national observations of how populist leaders employed populist discourse during the COVID-19 crisis in both Europe and the Americas.

It goes without saying that the selected cases cannot capture the full range of populist manifestations. Nonetheless, we include all instances that the literature—following the above minimal definition—classifies as populist, provided that they were in government during the period under study and for which relevant data are available.

To ensure maximum comparability and representativeness, the cases were selected based on specific criteria outlined in the Supplementary Materials, such as regional diversity, ideological orientation, political system, and centralization of power (see Table 1). After careful consideration of medical populist speeches of populists across the regions, the research team selected two populist leaders from Europe (Viktor Orbán and Igor Matovič), two from North America (Donald Trump and Andrés Manuel López Obrador), two contrasting examples of South American authoritarianism (Jair Bolsonaro and Nicolás Maduro), and one emerging populist figure with authoritarian tendencies from Central America (Nayib Bukele). For reasons related to coalition status or established authoritarian rule, we excluded Matteo Salvini in Italy and Daniel Ortega in Nicaragua respectively—see footnote4. By authoritarian, we refer to the tendencies of authoritarian submission and authoritarian aggression (Adorno et al. 1950; Altemeyer 1981). Right-wing authoritarianism in particular includes the belief in a strictly ordered hierarchical society demanding submission to authority and social conventions (Mudde 2007; Duckitt and Bizumic 2013; Rydgren 2018).

Table 1.

Case selection5.

Table 1.

Case selection5.

| Region | Europe | North America | Central America | South America | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | HUN | Slovakia | US | Mexico | Salvador | Brazil | Venezuela |

| Populist leader, political party | Viktor Orbán, Hungarian Civil Alliance (Fidesz) | Igor Matovič, Ordinary People and Independent Personalities (O’La’NO) | Donald Trump, Republican Party | Manuel López Obrador (AMLO), Together we will make History coalition | Nayib Bukele, Great Alliance for National Unity (GANA) | Jair Bolsonaro, Liberal Party (Partido Liberal) | Nicolás Maduro, United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV) |

| Terms in office | 1st term: June 1998–May 2002 2nd term: April 2010–March 2013 3rd term: April 2014–April 2018 4th term: April 2018–April 2022 5th term: April 2022–Present | March 2020–March 2021 | 1st term: January 2017–January 2021 2nd term: January 2025–Present | December 2018–September 2024 | 1st term: June 2019–April 2024 2nd term: April 2024–Present | January 2019–December 2022 | 1st term: March 2013–October 2019 2nd term: May 2018–July 2024 3rd term: January 2025–Present |

| Type of populism | Right-wing authoritarian | Right-wing | Right-wing | Left-of-center | Center-Right | Right-wing authoritarian | Left-wing authoritarian |

| Electoral & liberal democracy Index (LDI)6 | Electoral Autocracy (0.49): Mid-level 0.40 LDI | Electoral Democracy+ (0.82): Mid-Level 0.72 LDI | Liberal Democracy (0.80): Mid-level 0.70 LDI | Electoral Democracy (0.71): Mid-level 0.49 LDI | Electoral Democracy (0.63): Mid-level 0.44 LDI | Electoral Democracy (0.67): Mid-level 0.51 LDI | Electoral Autocracy (0.23): Least Democratic (0.09) |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

6. Analysis and Results7

Before assessing our theoretical expectations, we first apply descriptive statistics to determine the levels of medical populism and define individual medical populist profiles in order to provide insight into the different leadership styles of the actors. Second, we evaluate the hypotheses by investigating five causal pathways: (1) the relationship between populism and medical issues; (2) the impact of ideology; (3) the impact of traditional and alternative medicine; (4) the impact of national healthcare systems; and (5) the impact of the degree of power centralization within each country. As mentioned earlier, the detailed definition of medical populism and the coding system in this study are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

6.1. Medical Populism as an Expression of Anti-Establishment Politics

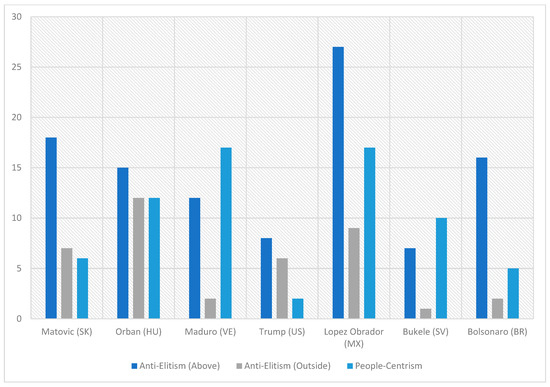

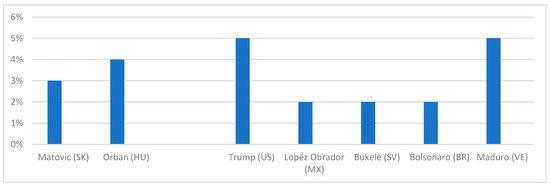

Who are the culprits in a medical crisis? In the medical populism playbook, blame for the pandemic is typically attributed to outgroups, to those above (elites) and below (e.g., minorities, foreigners or migrants). Figure 1 shows that medical populists primarily direct their antagonism against those perceived as being “above” the people (e.g., scientific and business/political elites). Figure 2 shows that populist leaders across all regions generally employ an anti-elitist narrative, portraying themselves as protectors of the people against perceived external threats8. There are however significant differences in how various populists define their in-group, “the people,” the out-groups they exclude, and in how they link popular sovereignty and nationalism to scientific claims9.

Figure 1.

Populist claims per category (relative frequency of claims, in percentage)10. Source: Elaborated by the authors. Note: Frequencies are expressed as percentages relative to the full text of each speech.

Figure 2.

Different types of anti-elitism (relative frequency of claims), in percentage11 Source: Elaborated by the authors. Note: Frequencies are expressed as percentages relative to the total coded content of each speech.

Maduro’s discourse is particularly people-centric, followed by Bukele and AMLO. As Figure 1 shows, left-wing actors AMLO and Maduro emphasize a broad and inclusive conception of “the people” that includes all social classes, rural and urban populations, and religious communities. AMLO, Maduro, and Bolsonaro largely blame neoliberalism, economic elites, and international organizations while portraying themselves as defenders of national sovereignty against foreign interference: AMLO and Maduro target neoliberalism and foreign entities, with Maduro accusing the U.S. of economic sabotage and AMLO blaming vaccine shortages on international organizations.

Generally, the diagnostic framing confirms the populist master frame positing an antagonism between the people and elites. However, we note that contrary to recent research on science populism (see Mede et al. 2020), scientific elites are not the primary target in discursive framing. Instead, blame is more commonly directed at pharmaceutical companies as well as traditional populist adversaries, such as international organizations (IOs), the European Union, business elites, national experts, and various out-groups (“outsiders”).

AMLO, along with Maduro regularly invokes anti-globalization, anti-neoliberal, anti-Western rhetoric, while advocating policies based on alternative knowledge. Ideologically, both left-wing populists primarily target economic elites and big business, while also condemning the media as a tool of the opposition. European leaders Orbán and Matovič primarily target the EU, portraying it as an overreaching and ineffective institution that undermines national sovereignty.

In terms of people-centrism, Trump uses a narrower definition of “the people,” focusing primarily on national identity, security and nativism. Similarly to Matovič, Bolsonaro, and Bukele, he frequently frames Americans as victims of both foreign adversaries, such as China and the WHO, and domestic opponents, including the mainstream media and political elites. AMLO, Maduro, and Orbán, on the other hand, portray the people as strong, powerful, and even superior12. Bolsonaro and Trump exhibit the most consistent anti-elite rhetoric targeting specifically the media, political opposition, international institutions such as the WHO—framing them as complicit with foreign interests and pharmaceutical companies. Bukele combines anti-opposition, anti-business, and anti-science rhetoric, claiming that both national and international actors obstructed his pandemic response.

The diagnostic and prognostic framing used by populists reveals discursive strategies that serve both to deflect criticism and to reinforce alignment with their electoral bases amid a contested crisis context. By shifting blame from domestic governance failures to international and elite actors, populist leaders consolidate power and legitimize their reliance on selective national expertise and mainstream policies. This pattern aligns with research suggesting that populist actors reframe crises to justify their authority while preserving the narrative of popular sovereignty.

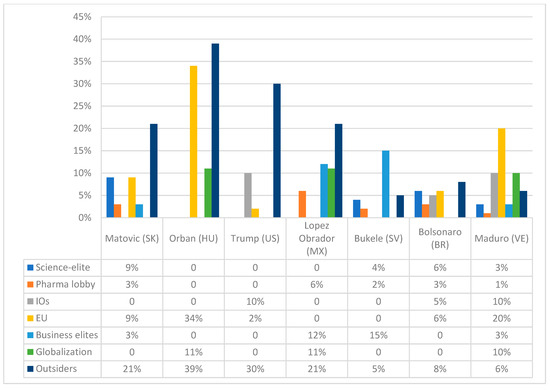

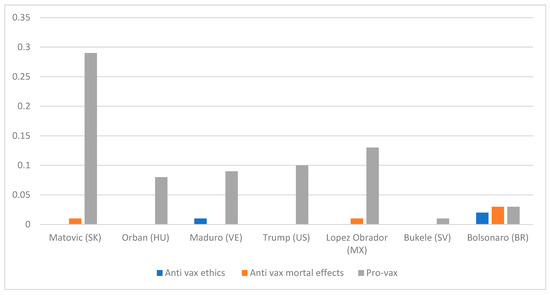

Turning to the medical dimension and thus to motivational framing, Bukele endorses both mainstream science and alternative remedies, albeit with varying emphasis. This pattern of calculated ambivalence is shared by several actors, who simultaneously reference public health authorities while promoting unproven treatments. Obrador and Matovič follow a similar discourse. In contrast, Trump and Bolsonaro diverge by explicitly dismissing mainstream science and playing down the severity of the pandemic. Orbán’s engagement with pseudoscience is limited, but he does promote the drug Favipiravir13. Figure 3 displays the relative frequencies of populist discourse and unconventional medical claims, while the Supplementary Materials, Section C details the specific misinformation and remedies referenced.

Several key findings emerge that are summarized in Figure 4, which groups leaders by region and ideology. Bolsonaro, Maduro, Trump, and AMLO followed by Bukele are biggest promoters of miracle cures. Latin American populist leaders often invoke spiritual guidance but generally exhibit a bifurcated pattern. Right-wing leaders Bolsonaro and Bukele prioritize alternative science and pseudoscientific solutions, while radical leftist Maduro emerges as the strongest advocate of traditional medicine, ranking highest across all related health policy indicators.

Figure 4.

Relative frequencies of populism and unconventional remedies, in percentage15. Source: Elaborated by the authors. Note: Frequencies are expressed as percentages relative to the full text of each speech.

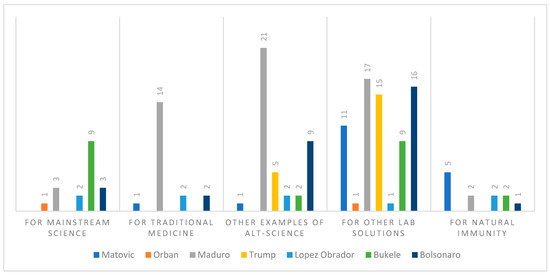

6.2. Conspiratorial and Anti-Vaccine Discourse

Turing to the analysis of the discourse, we find that prognostic and motivational framing involves narratives in which populist leaders warn of crisis unless granted special freedoms to implement their policies. As we can see in Figure 5, which details the frequency of conspiracy claims by region (Europe and the Americas), all actors, but especially Trump and Maduro, use conspiracies—see Supplementary Materials—in their advocacy of medical populism, by alleging hidden plots designed to undermine national efforts to manage the health crisis. Matovič claims for instance:

Figure 5.

Total frequencies of conspiratorial claims targeting foreign actors, by percentage. Source: Elaborated by the authors. Note: Frequencies are expressed as percentages relative to the total coded content of each speech.

We in Slovakia have more and more dead and dying people every day. In this situation, I am very sorry that our coalition partner has literally decided to experiment on people (…) And I think I pulled off a small miracle. 2 million Sputnik 5 vaccines for Slovakia by 06-202116.

Conspiracy theories often target foreign actors, global institutions, and political opponents. For instance, Trump claimed that the novel coronavirus was a bioweapon released by China, while Bolsonaro characterized international efforts to suppress alternative treatments as conspiracies led by pharmaceutical companies. Orbán blamed migration for spreading the virus, and Bukele and Matovič accused domestic elites of sabotaging health measures for political or economic gain. These narratives reflect and reinforce populist ideas about elites and foreign malign influences.

Figure 6 illustrates the ambivalent stance of populist leaders in power toward vaccines. While many promoted unproven remedies, they simultaneously supported vaccination campaigns. A notable exception is Jair Bolsonaro, who actively propagated anti-vaccine narratives. His opposition was grounded in ethical concerns (“anti-vax ethics”) and fears of potentially fatal side effects (“anti-vax mortal effects”). He further framed these concerns within a broader conspiracy, alleging a global campaign against early treatment methods and their advocates.

Figure 6.

Relative frequency of vaccine policies, by percentage Source: Elaborated by the authors. Note: Frequencies are expressed as percentages relative to the total coded content of each speech.

7. Discussion

Turning to the hypotheses, we first note that all populists in government, with the exception of Orbán, made considerable use of medical populism in their speeches. This is true for both radical right and left types of populism, as well as from Europe and America. The use of medical populism is not uniform, but the pattern is rarely what the literature would lead us to expect. These patterns confirm Brubaker’s (2021) observation of the pandemic’s paradox for populists: needing crisis to legitimate themselves while presenting themselves as the sole saviors charged with resolving it.

7.1. Populism and Medical Claims

The assumption in Hypothesis 1a, that polarizing discourse results in the spread of medical misinformation, cannot be validated: Figure 4, which compares polarization (populist claims) and unconventional medical claims across actors, indicates that four of seven cases do not fit the hypothesized pattern. Only for the cases Maduro, Bolsonaro, and Trump do we find this congruence. Thus, we cannot support Hypothesis 1a, but the expected relationship was clearly present in three of the seven cases.

7.2. Medical Populism and Ideology

The data does not support Hypothesis 1b, which suggests that the way radical right- and left-wing populists disseminate medical misinformation is different. The assumption that actors with left-wing ideologies would be less likely to spread misinformation because they rely on science and rational policies cannot be confirmed and Hypothesis 1b is consequently rejected. But this suggests that the core of medical populism is more important than its left- or right-wing host ideologies.

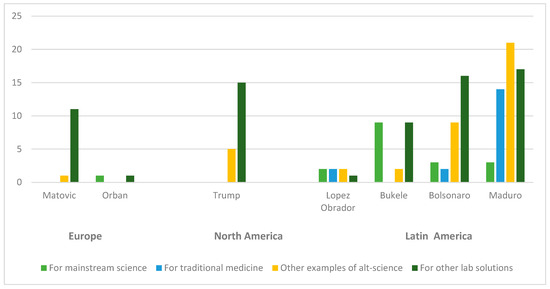

7.3. Frequency of Traditional or Alternative Forms of Medicine in Latin America

The analysis leads to a qualified support for Hypothesis 2a, which states that Latin American populists are more likely to promote traditional and folk medicine: as we can see in Figure 7, Latin American leaders demonstrate an inclination towards traditional medical remedies, a characteristic not prevalent among other leaders, except for Bukele. This anomaly in Bukele’s discourse is plausibly linked to his active advocacy for unproven chemical COVID-19 treatments, notably the distribution of ‘COVID-19 kits’ containing ivermectin, which lacked scientific validation (Requejo Domínguez et al. 2023).

Figure 7.

Total frequency of unconventional remedies, sorted by region. Note: Figure 7 illustrates the total frequencies of the coded variables.

7.4. Quality of Health Infrastructure and Medical Populism

Hypothesis 2b links the likelihood of engaging in medical populism with the quality of the health infrastructure. Figure 7 shows performance data on access to essential health services from Universal Health Coverage Index 2021 along with the scores of medical populism per actor. The findings suggest that in countries with weaker health infrastructure—particularly Venezuela, Mexico, and El Salvador, where conventional healthcare is already limited—populist leaders were somewhat more likely to embrace medical populism. However, the data also point to other factors that matter. Yet, only Hungary is a clear outlier here. Nonetheless, our empirical expectation is partially supported.

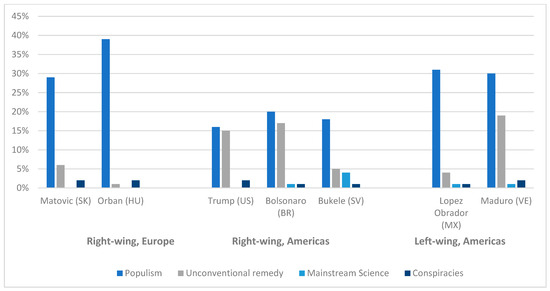

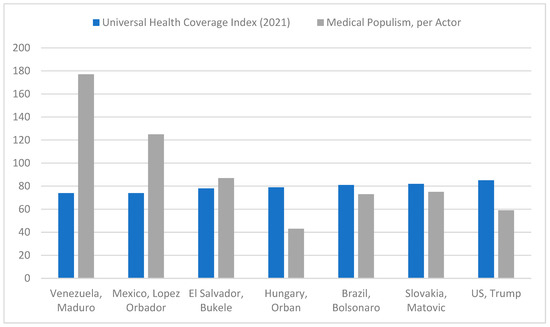

7.5. Medical Populism and Power Consolidation

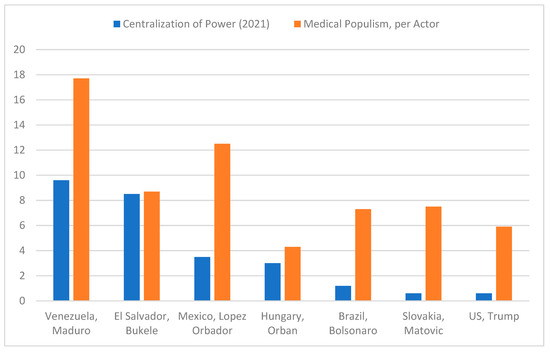

Central to the argument of our third hypothesis is that leaders with a high degree of power centralization would have less need for medical populism, meaning that medical populism would be used to increase political influence and power.

Our results, however, show that power centralization may increase the need for medical populism rather than reduce it, considering that the promotion and support of medical misinformation are more common among populist leaders with higher levels of power consolidation: Nicolás Maduro (Venezuela), Andrés Manuel López Obrador (Mexico), and Nayib Bukele (El Salvador). Consistent with other research findings, our analysis confirms that populist governance frequently sidesteps traditional, evidence-based, institutional, and democratic norms, fostering illiberal and autocratic tendencies. Orbán is a notable exception, given his comparatively lower involvement despite his high degree of power centralization. Here, the explanation may lie in Orbán’s specific type of populism. As illustrated in Figure 8, the regimes that exhibit the most centralized power also tend to employ a high degree of medical populism. This suggests an alternative underlying logic. It is not the drive to consolidate power, but rather the need to defend a consolidated and concentrated power that is correlated with a greater tendency towards disinformation and post-truth-telling. However, it is crucial to reiterate that numerous factors influence such a comprehensive comparison, and the findings presented here are merely indicative of a general trend, not a definitive conclusion. However, they do allow us to reject our hypothesis.

Our findings (Figure 9) align with Olivares-Jirsell and Hellström (2023), who show how populists use a personalized crisis management narrative to sustain proximity with the people, oscillating between the performance of crisis and adjustments to institutional and scientific constraints. Similarly, leaders such as Bukele or AMLO fused state authority with popular authenticity, while Orbán and Trump alternated between rejecting expertise and invoking paternal reassurance. This perspective highlights medical populism as not only anti-elitist rhetoric but also a mode of governance that reshapes the emotional bond between leader and people during crises.

Figure 9.

Centralization of Power Index (Ascending) & Medical Populism (total frequency)18. Source: V-Dem (data on 2021). Note: Derived from expert estimates and the V-Dem index, this measure assesses the degree to which the executive operates without constraints from the legislature, judiciary, electoral management bodies, and other oversight institutions. The index ranges from 0 (least centralized) to 1 (most centralized). The medical populism frequencies illustrate the total frequencies of the coded variables in speeches.

8. Conclusions

With this paper we offer original empirical insights into the strategic deployment of medical populism and operationalize medical populism by analyzing seven populist leaders across the Americas and Europe. Thereby, we focus on the extent and forms through which medical populism is strategically deployed to challenge establishment authority, mobilize public support, and promote alternative modes of governance. We first outline the medical populist profiles of the actors to then explore five explanatory pathways: (1) the relationship between populism and medical issues, and the roles of (2) ideology, (3) traditional and alternative medicine, (4) national health systems, and (5) the degree of power centralization within each country.

We demonstrate that, in both regions, medical populism is used in populist speeches to portray public health emergencies as failures of the political establishment and disseminate misleading health information as well as conspiracies, while at the same time presenting themselves as champions of “the people”. The central finding is that consolidated political power and regional health constraints play a greater role than ideology in driving medical populism: contrary to our initial hypothesis, a higher degree of centralized political power correlates positively with medical populism in the majority of cases, suggesting that autocratic tendencies reinforce medical populism. We suggest that healthcare infrastructure and the cultural acceptance of traditional medicine, especially in Latin America, influence the use of medical populism. Ideology is less predictive, and all leaders rely on oversimplified narratives and conspiratorial framing that challenge mainstream science and international cooperation.

Our analysis also shows that, in diagnostic framing, populist leaders generally attribute the causes of crises not to domestic mismanagement but to external or elite forces, thereby externalizing responsibility and preserving their image as defenders of “the people.” Through prognostic framing, they propose solutions that reinforce their own leadership—such as relying on selective national expertise or mainstream policy tools—while claiming these measures embody popular will rather than technocratic imposition. Finally, motivational framing combines appeals to collective resilience and trust in leadership with eclectic symbolic gestures, for instance endorsing both scientific and alternative remedies, to mobilize diverse segments of the population. Together, these interconnected frames allow populists to reinterpret crises as evidence of their necessity, using crisis discourse as a means of both justification and consolidation of power.

The implications of this study extend beyond academic research: medical populist governance actively erodes trust in evidence-based and multilateral policymaking around the world. To allow for a more comprehensive understanding of the global phenomenon that medical populism represents, and its potential links to authoritarianism and other forms of illiberalism, it seems important to include the emerging economies to examine the influence of factors such as misinformation, traditional cures, and power consolidation.

Ultimately, researchers from all disciplines should focus more on the supply-side mechanisms of medical and scientific misinformation, particularly the role of non-state actors, media ecosystems, religious organizations, and digital platforms and their use of populist medical narratives and normalizing anti-science rhetoric.

As a qualitative, case-based study, the findings are not intended to be statistically generalizable across all populist governments or crises. The analysis focuses on a small number of leaders and speeches, selected for their relevance rather than representativeness. The patterns identified should therefore be read as analytical generalizations, illustrative of broader mechanisms linking populist discourse and crisis performance, rather than as universal tendencies. Future research using larger samples or mixed methods could further test the scope and variation of these dynamics.

With the challenges of making evidence-based policies during global health crises increasing, future research should focus on new approaches to strengthen institutional safeguards, improve health communication, and combat anti-science rhetoric in public policy. Developing robust public transparency mechanisms to combat medical populism in the public sphere and mitigate its long-term effects, particularly with regard to future crises, appears as an urgent priority.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/socsci14110665/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.J.-A. and R.H.; methodology, A.J.-A.; software, A.J.-A.; validation, A.J.-A. and R.H.; formal analysis, A.J.-A.; investigation, A.J.-A.; resources, A.J.-A.; data curation, A.J.-A. writing—original draft preparation, A.J.-A.; writing—review and editing, A.J.-A. and R.H.; visualization, A.J.-A.; supervision, R.H.; project administration, A.J.-A. and R.H.; funding acquisition, A.J.-A. and R.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Open Access Funding by the University of Salzburg. This research was funded in whole or in part by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) [10.55776/DOC 118]. For open access purposes, the author has applied a CC BY public copyright license to any author accepted manuscript version arising from this submission.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request, due to the large size of the dataset.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Aurel Hauxhiu and Don Salihu of the University of Salzburg, Austria, for providing technical coding support, which was funded by the Salzburg Center of European Union Studies and the Political Science Department of the University of Salzburg.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The definitions of key terms used in this paper are as follows: “panacea” is used to regroup all definitions of the following: medical misinformation is defined as “false, misleading, or unsubstantiated medical information” (see Nyhan and Reifler 2010, p. 304) related to unproven drugs and treatments (Taccone et al. 2022). Pseudo-science refers to inherently false or unfounded information that lacks scientific validity (Hansson 1996). Alternative science encompasses claims situated at the intersection of various non-mainstream medical approaches, including natural medicine, complementary medicine, non-academic medicine, unconventional medicine, holistic medicine, paramedicine, partial evidence, pseudo-science, and conspiracy theories (Casarões and De Magalhães 2021). |

| 2 | For details on medical claims promoted by populists in this project, refer to Section C of the Supplementary Materials. |

| 3 | For further information on the framing and coding process please refer to the Supplementary Materials. |

| 4 | The Italian politician Matteo Salvini is not included in this analysis as he has not served as head of government during the pandemic, and Italy’s shifting political landscape during his tenure resulted in fluctuating policy approaches rather than a consistent populist governance model. Daniel Ortega (Nicaragua) aligns more closely with authoritarian rule rather than populism in the conventional sense, making it difficult to assess Salvini’s actions and underlying motives. His administration’s extreme and highly irregular approach to COVID-19—marked by a near-total denial of the pandemic and an absence of mitigation policies—positions Nicaragua as a significant outlier, making direct comparisons with other cases in this study less analytically useful. |

| 5 | The classification of leaders as “left” or “right” populists remains contested, particularly in Latin America. Scholars on the left debate whether figures like Maduro or López Obrador genuinely represent progressive populism or authoritarian governance. These labels are thus used here as heuristic shorthand rather than fixed ideological categories. |

| 6 | Electoral democracy index V-Dem (2024a); Liberal democracy index V-Dem (2024b). |

| 7 | The quotations presented in this chapter have been translated from their original language, except for those of V. Orban, speech 1 and 2. For details on case selection and details on the speeches please refer to Supplementary Materials. |

| 8 | The term “people-centrism” signifies the emphasis on the proximity between the populist leader and homogenous “people” or heart-landers as well as the alignment of the leader’s values with those of “the people”. According to Taggart, ‘the heartland’ is the place “in which, in the populist imagination, a virtuous and unified population resides” (Taggart 2000, p. 4); whereas the people refer to an idealized conception of the community” (Taggart 2002, p. 274). |

| 9 | For detailed data and individual profile descriptions of the cases, please consult the Supplementary Materials and the summary tables. |

| 10 | As used in Figure 1, (i) “anti-elitism from the above” includes blaming national political elites, scientific elites, International Organizations, the EU, economic elites; (ii) “anti-elitism from the outside” means the blaming of non-national elite”; and (iii) “People-centrism” means references to the people in a populist fashion. |

| 11 | The results indicate what percentage of the coded length of the speeches was coded with the given code, relative to the entire coded length of each speech, per actor. The term “against own experts” encompasses criticisms directed at national experts, while “for own experts” denotes support or endorsement of national experts. “International (intl.) leaders” blames other international actors, while the variable “outsiders” regroups minorities, elites, imperialist or economic forces outside, or the perceived aliens below. “Scientific elite” focuses on accusations aimed at scientific authorities. “Blame Pharma Lobby” directs criticism towards the pharmaceutical industry and its associated lobbies. “Blame Intern. Org.” targets International Organizations (IOs). “Blame EU” points to criticisms directed at the European Union. |

| 12 | Orbán (Hungary) and Bukele (El Salvador) place stronger emphasis on nationalism and sovereignty, presenting “the people” as a unified national body that must be defended against external interference. Orbán’s rhetoric targets EU bureaucrats and migration policies, while Bukele blends religious and nationalist elements. Matovič (Slovakia) highlights national unity and directs his attacks primarily at the EU, opposition leaders, and critical media outlets. |

| 13 | Orban, sp. 3, 30.10.2020. |

| 14 | The results show how many times the speeches were coded with the given claim. “For ‘mainstream’ science” applies to claims advocating for policies grounded in scientific evidence as acknowledged by national and international institutions, including the WHO. “For traditional medicine” section highlights the endorsement of traditional remedies. “Other lab solutions” points to the use of synthetic or lab-created pharmaceutical drugs, as opposed to natural substances or folk remedies. The term “natural immunity” in the graph signifies advocating for the body’s inherent immune response as a defense against the virus. The “Other examples of alt-science” category encompasses claims that commend various individuals or entities advocating for alternative science-based treatments and pharmaceuticals. |

| 15 | Unconventional remedies include traditional, folk medicine as well as unproven chemical substances and other alternative anti-mainstream medical claims. |

| 16 | I. Matovič, Sp. 2, 19.02.2021. |

| 17 | Defined as the average coverage of essential services based on tracer interventions that include reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health, infectious diseases, non-communicable diseases and service capacity and access, among the general and the most disadvantaged population. The indicator is an index reported on a unitless scale of 0 to 100, which is computed as the geometric mean of 14 tracer indicators of health service coverage. The tracer indicators are as follows, organized by four components of service coverage: 1. Reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health 2. Infectious diseases 3. Noncommunicable diseases 4. Service capacity and access. Source: WHO (2025). |

| 18 | Medical populism does not include conspiracies. |

References

- Adler, Emanuel, and Alena Drieschova. 2021. The Epistemological Challenge of Truth Subversion to the Liberal International Order. International Organization 75: 359–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adorno, Theodor W., Else Frenkel-Brunswik, Daniel J. Levinson, and Nevitt Sanford. 1950. The Authoritarian Personality. New York: Harper & Brothers. [Google Scholar]

- Altemeyer, Bob. 1981. Right-Wing Authoritarianism. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press. [Google Scholar]

- Aslanidis, Paris. 2016. Is populism an ideology? A refutation and a new perspective. Political Studies 64 S1: 88–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardi, Luciano, Stefano Bartolini, and Alexander H. Trechsel. 2014. Responsive and responsible? The role of parties in twenty-first century politics. West European Politics 37: 235–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, Eirikur. 2018. Conspiracy & Populism. In Palgrave Macmillan. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordignon, Frédérique. 2023. Alternative science, alternative experts, alternative politics. The roots of pseudoscientific beliefs in Western Europe. Journal of Contemporary European Studies 31: 1469–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brubaker, Rogers. 2021. Paradoxes of populism during the pandemic. Thesis Eleven 164: 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canovan, Margaret. 1999. Trust the People! Populism and the Two Faces of Democracy. Political Studies 47: 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canovan, Margaret. 2005. The People. Cambridge: Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Caramani, Daniele. 2017. Will vs. reason: The populist and technocratic forms of political representation and their critique to party government. American Political Science Review 111: 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casarões, Guilherme, and David A. De Magalhães. 2021. The hydroxychloroquine alliance: How far-right leaders and alt-science preachers came together to promote a miracle drug. Revista De Administração Pública 55: 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine, Daniel, Jennifer Gaskell, Will Jennings, and Gerry Stoker. 2020. Trust and the Coronavirus Pandemic: What are the Consequences of and for Trust? An Early Review of the Literature. Political Studies Review 19: 274–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wilde, Pieter, Ruud Koopmans, and Michael Zürn. 2014. The Political Sociology of Cosmopolitanism and Communitarianism: Representative Claims Analysis. Zeitschrift für Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft 14: 59–61, Discussion Paper. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, Thomas. 2013. Bringing values and deliberation to science communication. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 110: 14081–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckitt, John, and Boris Bizumic. 2013. Multidimensionality of right-wing authoritarian attitudes: Authoritarianism conservatism-traditionalism. Political Psychology 34: 841–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberl, Jakob-Moritz, Robert Huber, and Esther Greussing. 2021. From populism to the “plandemic”: Why populists believe in COVID-19 conspiracies. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion & Parties 31 S1: 272–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazal, Tanisha M. 2020. Health Diplomacy in Pandemical Times. International Organization 74 S1: E78–E97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filc, Dani. 2015. Latin American inclusive and European exclusionary populism: Colonialism as an explanation. Journal of Political Ideologies 20: 263–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, Nuria, Paolo Graziano, and Myrto Tsakatika. 2021. Varieties of Inclusionary Populism? SYRIZA, Podemos and the Five Star Movement. Government and Opposition 56: 163–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freelon, Deen. 2013. ReCal2: Reliability for 2 Coders. Available online: https://Dfreelon.Org/Utils/Recalfront/Recal2/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Gerring, John. 2007. Case Study Research: Principles and Practices. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Górka, Jakub K. 2021. The Populist Identity of the Promoters of Alternative Medicine. Politeja 17: 131–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gugushvili, Alexi, Jonathan Koltai, David Stuckler, and Martin McKee. 2020. Votes, populism, and pandemics. International Journal of Public Health 65: 721–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallin, Daniel C., Sabina Mihelj, Paulo Ferracioli, Nithyanand Rao, Katarzyna Vanevska, Ana Stojiljković, Beata Klimkiewicz, Danilo Rothberg, and Vávlav Štětka. 2024. Pandemic communication in times of populism: Politicization and the COVID communication process in Brazil, Poland, Serbia and the United States. Social Science & Medicine 360: 117304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, Lawrence C., and Thomas G. Safford. 2021. Ideology affects trust in science agencies during a pandemic. The Carsey School of Public Policy at the Scholars’ Repository, 414. Available online: https://carsey.unh.edu/publication/ideology-affects-trust-science-agencies-during-pandemic (accessed on 3 November 2021).

- Hansson, Sven. O. 1996. Defining Pseudo-Science. Philosophia Naturalis 33: 169–76. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann, Christopher. 2016. Postneoliberal Public Health Care Reforms: Neoliberalism, Social Medicine, and Persistent Health Inequalities in Latin America. American Journal of Public Health 106: 2145–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, Kirk A., ed. 2010. Measuring the Populist Discourse of Chavismo. In Venezuela’s Chavismo and Populism in Comparative Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 50–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, Kirk A., Rosario Aguilar, Bruno Castanho Silva, Erin K Jenne, Bojana Kocijan, and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser. 2019. Global Populism Database v2. [Dataset]. Harvard Dataverse. Available online: https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/LFTQEZ (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- Heinisch, Reinhard, and Klaudia Koxha. 2023. Sovereignty and Populism. In Populism and Key Concepts in Social and Political Theory. Edited by Carlos de la Torre and Oscar Mazzoleni. Leiden: Brill, vol. 4, pp. 114–35. [Google Scholar]

- Heinisch, Reinhard, and Oscar Mazzoleni. 2021. Fixing the taxonomy in populism research: Bringing frame, actor and context back in. In Political Populism. Baden-Baden: Nomos, pp. 111–30. [Google Scholar]

- Heinisch, Reinhard, Duncan McDonnell, and Annika Werner. 2020. Equivocal Euroscepticism: How populist radical right parties can have their EU cake and eat it. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 59: 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinisch, Reinhard, Oscar Gracia, Andrés Laguna-Tapia, and Claudia Muriel. 2024. Libertarian Populism? Making Sense of Javier Milei’s Political Discourse. Social Sciences 13: 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeley, Brian. 1999. Of conspiracy theories. Journal of Philosophy 96: 109–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemppainen, Laura M., Teemu T. Kemppainen, Jutta A. Reippainen, Suvi T. Salmenniemi, and Pia H. Vuolanto. 2018. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in Europe: Health-related and sociodemographic determinants. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 46: 448–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuckartz, Udo, and Stefan Rädiker. 2019. Analyzing Qualitative Data with MAXQDA: Text, Audio, and Video. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laclau, Ernesto. 1977. Politics and Ideology in Marxist Theory: Capitalism, Fascism, Populism. London: New Left Books. [Google Scholar]

- Laclau, Ernesto. 2005. On Populist Reason, 1st ed. London: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Lasco, Gideon. 2020. Medical populism and the COVID-19 pandemic. Global Public Health 15: 1417–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lasco, Gideon, and Nicole Curato. 2019. Medical populism. Social Science & Medicine 221: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, Martin, Alexi Gugushvili, Jonathan Koltai, and David Stuckler. 2020. Are Populist Leaders Creating the Conditions for the Spread of COVID-19? Comment on “A Scoping Review of Populist Radical Right Parties’ Influence on Welfare Policy and its Implications for Population Health in Europe”. International Journal of Health Policy and Management 10: 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, Kathleen R., and Abraham L. Newman. 2020. The Big Reveal: COVID-19 and Globalization’s Great Transformations. International Organization 74 S1: E59–E77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mede, Niels G., Mike S. Schäfer, and Tobias Füchslin. 2020. The SCIPOP Scale for Measuring Science-Related Populist Attitudes in Surveys: Development, Test, and Validation. International Journal of Public Opinion Research 33: 273–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijers, Maurits J., and Andrej Zaslove. 2021. Measuring populism in political parties: Appraisal of a new approach. Comparative Political Studies 54: 372–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mény, Yves, and Yves Surel. 2000. Par le peuple, pour le peuple: Le populisme et les démocraties. Florence: Cadmus EUI. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/1814/8154 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Moffitt, Ben. 2015. How to perform crisis: A model for understanding the key role of crisis in contemporary populism. Government and Opposition 50: 189–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffitt, Ben. 2016. The Global Rise of Populism. In Performance, Political Style, and Representation, 1st ed. Redwood City: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffitt, Ben. 2020. Populism. London: Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Mouffe, Chantal. 1999. Deliberative democracy or agonistic pluralism? Social Research 66: 745–58. [Google Scholar]

- Mudde, Cas. 2007. Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mudde, Cas, and Cristobal R. Rovira Kaltwasser. 2012a. Exclusionary vs. Inclusionary Populism: Comparing Contemporary Europe and Latin America. Government and Opposition 48: 147–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudde, Cas, and Cristobal R. Rovira Kaltwasser, eds. 2012b. Populism in Europe and the Americas: Threat or Corrective for Democracy? Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nyhan, Brendan, and Jason Reifler. 2010. When Corrections Fail: The Persistence of Political Misperceptions. Political Behavior 32: 303–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivares-Jirsell, Jellen, and Anders Hellström. 2023. Activities and Counterstrategies; Populism during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Populism 6: 107–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, Thaiane, Simone Evangelista, Marcelo Alves Dos Santos, Jr., and Rodrigo Quinan. 2021. “Those on the Right Take Chloroquine”: The Illiberal Instrumentalisation of Scientific Debates during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Brasil. Javnost—The Public 28: 165–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Requejo Domínguez, José A., Dolores Mino-León, and Veronika J. Wirtz. 2023. Quality of clinical evidence and political justifications of ivermectin mass distribution of COVID-19 kits in eight Latin American countries. BMJ Global Health 8: e010962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rieger, Marc O., and Mei Wang. 2022. Trust in Government Actions During the COVID-19 Crisis. Social Indicators Research 159: 967–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinaldi, Chiara, and Marleen P. M. Bekker. 2020. A Scoping Review of Populist Radical Right Parties’ Influence on Welfare Policy and its Implications for Population Health in Europe. International Journal of Health Policy and Management 10: 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ringe, Nils, and Lucio Rennó. 2022. Populists and the Pandemic: How Populists Around the World Responded to COVID-19. Abingdon: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Rooduijn, Matthijs, Andrea L. P. Pirro, Daphne Halikiopoulou, Caterina Froio, Stijn Van Kessel, Sarah L. De Lange, Cas Mudde, and Paul Taggart. 2023. The PopuList: A database of populist, far-left, and far-right parties using expert-informed qualitative comparative classification (EIQCC). British Journal of Political Science 54: 969–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooduijn, Matthijs, and Teun Pauwels. 2011. Measuring populism: Comparing two methods of content analysis. West European Politics 34: 1272–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rydgren, Jens, ed. 2018. The radical right: An introduction. In The Oxford Handbook of the Radical Right. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, Johnny. 2016. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Saurette, Paul, and Shane Gunster. 2011. Ears wide shut: Epistemological populism, argutainment and Canadian conservative talk radio on JSTOR. Canadian Journal of Political Science/Revue Canadienne De Science Politique 44: 195–218. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41300521 (accessed on 1 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Saward, Michael. 2010. The Representative Claim. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, Prerna. 2022. How Exclusionary Nationalism Has Made the World Socially Sicker from COVID-19. Nationalities Papers 50: 104–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, David A., and Robert D. Benford. 1988. Ideology, frame resonance, and participant mobilization. International Social Movement Research 1: 197–217. [Google Scholar]

- Taccone, Fabio S., Maya Hites, and Nicolas Dauby. 2022. From Hydroxychloroquine to Ivermectin: How unproven “cures” can go viral. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 28: 472–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taggart, Paul. 2000. Populism, 1st ed. London: Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Taggart, Paul. 2002. Populism and the pathology of representative politics. In Democracies and the Populist Challenge. Edited by Yves Mény and Yves Surel. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 62–80. [Google Scholar]

- Touchton, Michael, Felicia M. Knaul, Timothy McDonald, and Julio Frenk. 2023. The Perilous Mix of Populism and Pandemics: Lessons from COVID-19. Social Sciences 12: 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Törnberg, Petter, and Juliana Chueri. 2025. When Do Parties Lie? Misinformation and Radical-Right Populism Across 26 Countries. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 19401612241311886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Prooijen, Jan-Willem, and Karen M. Douglas. 2017. Conspiracy theories as part of history: The role of societal crisis situations. Memory Studies 10: 323–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Zoonen, Liesbet. 2012. I-Pistemology: Changing truth claims in popular and political culture. European Journal of Communication 27: 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V-Dem. 2024a. Processed by Our World in Data. Electoral Democracy Index (Best Estimate, Aggregate: Average) [Dataset]. V-Dem, “V-Dem Country-Year (Full + Others) v14” [Original Data]. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/distribution-electoral-democracy-index-vdem (accessed on 29 January 2025).

- V-Dem. 2024b. Processed by Our World in Data. Liberal Democracy Index (Best Estimate, Aggregate: Average) [Dataset]. V-Dem, “V-Dem Country-Year (Full + Others) v14” [Original Data]. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/liberal-democracy-index (accessed on 6 February 2025).