Students’ Emotions Toward Assessments: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

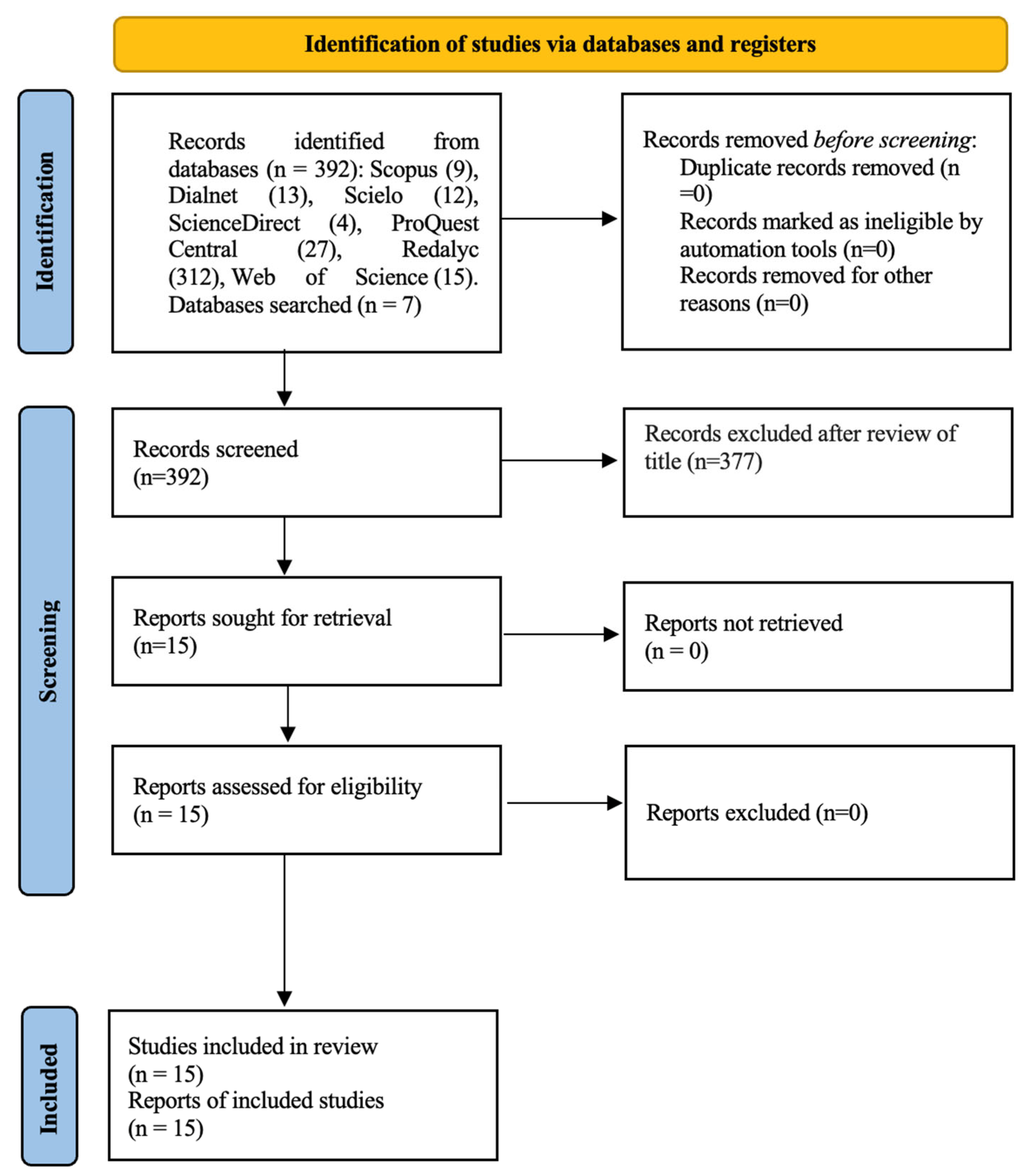

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Most Relevant Authors and Researchers

3.2. Q2: Geographical Distribution

3.3. Q3: Emotions and Assessment

3.4. Q4: Methodological Approaches

3.5. Q5: Emotional Patterns by Type of Assessment

3.6. Q6: Results and Conclusions of the Reviewed Studies

Limitations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abad, José Vicente, Santiago Otálvaro Arango, and Mateo Vergara Restrepo. 2021. Perceptions of the influence of anxiety on students’ performance on English oral examinations. Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios Educativos 17: 143–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila-Toscano, José Hernando, Laura Rambal Rivaldo, Kelly Oquendo-González, and Leonardo Vargas Delgado. 2021. Ansiedad ante exámenes en universitarios: Papel de engagement, inteligencia emocional y factores asociados con pruebas académicas. Psicogente 24: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basaknezhad, Soudabe, Razie Saeedi, and Mahnaz Mehrabizadeh. 2013. The study of perceived threat of test, cognitive test anxiety, looming maladaptive style, attributions to performance and fear of negative evaluation predictors of test anxiety in female high school students. Journal of Educational Sciences 20: 189–202. Available online: https://education.scu.ac.ir/article_10110.html?lang=en (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Bisquerra, Rafael. 2000. Educación emocional y bienestar. New York: Praxis. [Google Scholar]

- Bisquerra, Rafael. 2001. ¿Qué es la educación emocional? Temáticos de la Escuela Española I: 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Bisquerra, Rafael. 2020. Emociones: Instrumentos de medición y evaluación. Buenos Aires: Síntesis. [Google Scholar]

- Bisquerra, Rafael, and Èlia López-Cassà. 2021. Evaluation in emotional education: Instruments and resources; [La evaluación en la educación emocional: Instrumentos y recursos]. Aula Abierta 50: 757–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, David. 2021. Los exámenes como fuente de estrés. Cómo las evaluaciones pueden afectar el aprendizaje a través del estrés. JONED Journal of Neuroeducation 2: 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capafons, Juan, and Sosa Dolores. 1984. Técnicas de reducción de ansiedad. In Manual de Modificación de Conducta. Edited by Francisco J. Labrador Encinas. Madrid: Alhambra, pp. 229–64. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Ying-Fen. 2025. Three-dimensional sources of academic contingent self-worth and their links to perfectionism and academic emotions: Identifying the least vulnerable source. Educational Psychology 45: 437–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumbes-Chávez, Marilyn. 2018. Inteligencia emocional y estrés académico en estudiantes de secundaria de una institución educativa particular de Jauja, Junín. Inteligencia emocional y estrés académico en estudiantes. Master’s thesis, Universidad Cesar Vallejo, Lima, Peru. Available online: https://repositorio.ucv.edu.pe/bitstream/handle/20.500.12692/98135/Chumbe_CME-SD.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Damasio, Antonio. 2010. Y el cerebro creó al hombre. Barcelona: Editorial Destino. [Google Scholar]

- Darwin, Charles. 1872. The Expression of the Emotions in the Man and Animals. London: Jhon Murray. [Google Scholar]

- De la Fuente, Jesús, Paola Verónica Paoloni, Manuel Mariano Vera-Martínez, and Angélica Garzón-Umerenkova. 2020. Effect of levels of self-regulation and situational stress on achievement emotions in undergraduate students: Class, study and testing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17: 4293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denkci Akkaş, Ferdane, Selami Aydın, Asiye Baştürk Beydillid, Tülin Türnük, and İlknur Saydam. 2020. Test anxiety in the foreign language learning context: A theoretical framework. Focus on ELT Journal 2: 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez Lara. 2018. Influencia de la inteligencia emocional y de la personalidad en las estrategias cognitivas de regulación emocional en la desaprobación de exámenes en estudiantes de psicología de una universidad privada de Lima. Doctoral thesis, Universidad de San Martín de Porres, Lima, Peru. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/tesis?codigo=344950 (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Fernández, M. Jesús, and Isabel Fialho. 2016. ¿Qué tipo de emociones experimenta el alumnado al ser evaluado con rúbrica? Revista Internacional de Evaluación y Medición de la Calidad Educativa 3: 42–56. [Google Scholar]

- Furlan, Luis Alberto. 2006. Ansiedad ante los exámenes. ¿Qué se evalúa y cómo? Evaluar 6: 32–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlan, Luis Alberto, and Gonzalo Martínez-Santos. 2023. Intervención en un caso de ansiedad ante exámenes, perfeccionismo desadaptativo y procrastinación. Revista Digital de Investigación en Docencia Universitaria 17: e1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Sha. 2024. Can artificial intelligence give a hand to open and distributed learning? A probe into the state of undergraduate students’ academic emotions and test anxiety in learning via ChatGPT. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning 25: 200–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Beracierto, Juleiky, Verónica Giovanna Mayorga-Núñez, Paolina Antonieta Figuera-Ávila, Amparo Marisol Guillen-Téran, and Cristian Vinicio Cunalata-Yaguache. 2024. Indicadores de ansiedad en estudiantes universitarios de enfermería de primer y segundo semestre de una universidad privada. Revista Científica Retos de la Ciencia 8: 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetz, Thomas, Anne C. Frenzel, Oliver Lüdtke, and Nathan C. Hall. 2010. Between-domain relations ofacademic emotions: Does having the same instructor make a difference? The Journal of Experimental Education 79: 84–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Peralta, Angelina G., and Mario Sánchez-Aguilar. 2023. Undergraduate students’ emotions around a linear algebra oral practice test. International Electronic Journal of Mathematics Education 18: em0735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusils, Carlos, Fabiana del Valle Sánchez, Luigi García Biagosch, Pía Andujar, and José Barrionuevo. 2021. La gestión de las emociones de los estudiantes universitarios y el rendimiento académico en los exámenes. Revista Argentina de Educación Médica 10: 33–41. Available online: https://ri.conicet.gov.ar/handle/11336/184298 (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Gutiérrez-Vergara, Samuel, Karen Córdova-León, Lincoyán Fernández-Huerta, and Karol González-Vargas. 2020. Emociones académicas frente al proceso de evaluación del aprendizaje: Un estudio en estudiantes de educación médica. FEM Revista de la Fundación Educación Médica 23: 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, Andy. 1998. The emotional practice of teaching. Teaching and Teacher Education 14: 835–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harley, Jason M., Nigel Mantou Lou, Yang Liu, Maria Cutumisu, Lia M. Daniels, Jacqueline P. Leighton, and Lindsey Nadon. 2021. University students’ negative emotions in a computer-based examination: The roles of trait test-emotion, prior test-taking methods and gender. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 46: 956–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hascher, Tina. 2010. Learning and emotion: Perspectives for theory and research. European Educational Research Journal 9: 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, Ronnel B., and Cherry Eron Frondozo. 2022. Variety is the spice of life: How emotional diversity is associated with better student engagement and achievement. British Journal of Educational Psychology 92: 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Breton, David. 2013. Por una antropología de las emociones. Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios Sobre Cuerpos, Emociones y Sociedad 4: 67–77. [Google Scholar]

- LeDoux, Joseph. 1999. El Cerebro Emocional. Barcelona: Ariel-Planeta. [Google Scholar]

- López-Cassá, Élia, and Rafael Bisquerra. 2023. Emociones epistémicas: Una revisión sistemática sobre un concepto con aplicaciones a la educación emocional. Revista Internacional de Educación Emocional y Bienestar 3: 35–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellado, Vicente, A. Belén Borrachero, María Brígido, Lina V. Melo, M. Antonia Dávila, Florentina Cañada, M. Carmen Conde, Emilio Costillo, Javier Cubero, Rocío Esteban, and et al. 2014. Las emociones en la enseñanza de las ciencias. Enseñanza de las Ciencias 32: 11–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez López, Mariza G., and Argelia Peña Aguilar. 2013. Emotions as Learning Enhancers of Foreign Language Learning Motivation. Issues in Teacher’s Professional Development 15: 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Miguel Tobal, Juan José, and Antonio Cano Vindel. 1990. La evaluación de la ansiedad. Situación presente y direcciones futuras. In Diagnóstico y Evaluación Psicológica. Madrid: Colegio Oficial de Psicólogos. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, David, Alessandro Liberati, Jennifer Tetzlaff, Douglas G. Altman, and The PRISMA Group. 2009. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Medicine 6: e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obregón-Cuesta, Ana Isabel, Luis Alberto Mínguez-Mínguez, Benito León-del-Barco, Santiago Mendo-Lázaro, Jessica Fernández-Solana, Josefa González-Santos, and Jerónimo J. González-Bernal. 2022. Psychometric Analysis and Contribution to the Evaluation of the Exams-Related Emotions Scale in Primary and Secondary School Students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 6770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, David. 2017. The action tendency for learning: Characteristics and antecedents in regular lessons. International Journal of Educational Research 82: 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paoloni, Paola Verónica, and Arabela Beatriz Vaja. 2013. Emociones de logro en contextos de evaluación: Un estudio en estudiantes universitarios. Revista Innovación Educativa 13: 47–62. Available online: https://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?pid=S1665-26732013000200009&script=sci_abstract (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Pekrun, Reinhard. 2006. The control-value theory of achievement emotions: Assumptions, corollaries, and implications for educational research and practice. Educational Psychology Review 18: 315–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, Reinhard. 2023. Mind and body in students’ and teachers’ engagement: New evidence, challenges, and guidelines for future research. British Journal of Educational Psychology 93 S1: 227–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, Reinhard. 2024. Control-Value Theory: From Achievement Emotion to a General Theory of Human Emotions. Educational Psychology Review 36: 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, Reinhard, and Raymond P. Perry. 2014. Teoría del valor de control de las emociones de logro. In International Handbook of Emotions in Education. Edited by A. Alexander, R. Pekrun and L. Linnenbrink-Garcia. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 120–41. [Google Scholar]

- Pekrun, Reinhard, Thomas Goetz, Anne C. Frenzel, Petra Barchfeld, and Raymond P. Perry. 2011. Measuring emotions in students’ learning and performance: The Achievement Emotions Questionnaire (AEQ). Contemporary Educational Psychology 36: 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, Reinhard, Thomas Goetz, Wolfram Titz, and Raymond P. Perry. 2002. Academic Emotions in Students’ Self-Regulated Learning and Achievement: A Program of Qualitative and Quantitative Research. Educational Psychologist 37: 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puente-Díaz, Rogelio, and Lizbeth Puerta-Sierra. 2025. Epistemic activities and epistemic emotions: The necessary yet insufficient conditions to generate, evaluate, and select creative ideas. Thinking Skills and Creativity 56: 101756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido Acosta, Federico, and Francisco Herrera Clavero. 2017. La Influencia De Las Emociones Sobre El Rendimiento Académico. Ciencias Psicológicas 11: 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putwain, David W., and Ben Aveyard. 2018. Is perceived control a critical factor in understanding the negative relationship between cognitive test anxiety and examination performance? School Psychology Quarterly 33: 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaño-Rodríguez, Diego Riaño. 2024. Configuración de escenarios didácticos mediados por TIC, para la formación emocional en la presentación de exámenes estandarizados. LATAM Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades 5: 384–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riegel, Kaitlin, and Tanya Evans. 2021. Student achievement emotions: Examining the role of frequent online assessment. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology 37: 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutz, Paul A., and Reinhard Ed Pekrun. 2007. Emotion in Education. Cambridge: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Segura, Jesús Marcos, María Luz Cacheiro González, and María Concepción Domínguez. 2020. Habilidades emocionales en profesores y estudiantes de Educación Media y Universitaria de Venezuela. Revista EDUCARE 24: 153–79. Available online: https://revistas.investigacion-upelipb.com (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Shapiro, Shawna. 2010. Revisiting the teachers’ lounge: Reflections on emotional experience and teacher identity. Teaching and Teacher Education 26: 616–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, Juan Carlos, Virgilio Ortega, and Ihab Zubeidat. 2003. Ansiedad, angustia y estrés: Tres conceptos a diferenciar. Revista Mal-Estar e Subjetividade/Fortaleza 3: 10–59. [Google Scholar]

- Weiner, Bernard. 2007. Examining Emotional Diversity in the Classroom. An Attribution Theorist Considers the Moral Emotions. In Emotion in Education. Edited by Paul A. Schutz and Reinhard Pekrun. Cambridge: Academic Press, pp. 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrano-Vélez, Wilson Alexander, María Fernanda Reyes-Santacruz, Edwar Salazar-Arango, and Andrea Annabella Del Pezo-Laínez. 2023. Los estados emocionales de estudiantes universitarios en la evaluación del aprendizaje. Digital Publisher 8: 245–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Language | Databases | Search Equations |

|---|---|---|

| English | Scopus, Web of Science, ProQuest, ScienceDirect | (emotions OR “achievement emotions”) AND (assessment OR evaluation OR test) AND student |

| Spanish | Dialnet, Redalyc, Scielo | emociones AND estudiantes AND exámenes |

| Author(s) | Number of References | Time Range | Key Themes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reinhard Pekrun et al. | 25 | 2000–2019 | Academic emotions: anxiety, motivation, control-value theory |

| José De la Fuente et al. | 16 | 2015–2020 | Self-regulation and coping: academic stress, academic performance |

| Patrick R. Goetz et al. | 12 | 2002–2019 | Classroom emotions: performance, enjoyment, boredom |

| Laura Furlan et al. | 10 | 2006–2023 | Test anxiety: perfectionism, psychological interventions |

| Peter D. MacIntyre et al. | 6 | 1989–1999 | Foreign language learning: anxiety, motivation, communication |

| Natalio Extremera et al. | 5 | 2004–2013 | Emotional intelligence: burnout, engagement, emotional well-being |

| Elaine K. Horwitz et al. | 5 | 1986–2010 | Foreign language anxiety: measurement scales, learning outcomes |

| Pablo Fernández-Berrocal et al. | 5 | 1999–2008 | Emotional intelligence in education: emotional education, instrument validation |

| Fernando G. Arana et al. | 5 | 2002–2016 | Assessment-related emotions: anxiety, evaluation, motivation, perfectionism |

| Samuel A. Domínguez-Lara et al. | 5 | 2016–2018 | Psychometric validation: anxiety, emotional regulation |

| John D. Mayer and Peter Salovey | 4 | 1995–2008 | Emotional intelligence theory: emotion and education |

| Sükran Aydın et al. | 4 | 2006–2020 | Foreign language anxiety: teacher feedback, individual differences |

| Author | Approach/Design | Instruments | Type of Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| García-Beracierto et al. (2024) | Quantitative Descriptive | Questionnaire | Descriptive analysis |

| Zambrano-Vélez et al. (2023) | Quantitative Descriptive | Questionnaire | Descriptive analysis |

| González-Peralta and Sánchez-Aguilar (2023) | Quantitative Descriptive | Questionnaires | Descriptive and correlational analysis |

| De la Fuente et al. (2020) | Quantitative Correlational | Questionnaires | Multivariate analysis (SEM, ANOVA, MANOVA) |

| Gutiérrez-Vergara et al. (2020) | Quantitative Correlational | Questionnaire | Inferential analysis (t-tests) |

| Abad et al. (2021) | Quantitative Correlational | Questionnaires | Correlational and regression analysis |

| Obregón-Cuesta et al. (2022) | Quantitative Correlational | Questionnaires | Multivariate analysis |

| Harley et al. (2021) | Quantitative Correlational | Questionnaires | Multilevel statistical modeling |

| Riegel and Evans (2021) | Quantitative Correlational | Questionnaires | Inferential analysis (ANOVA, regression) |

| Gao (2024) | Quantitative Quasi-experimental | Scales | Inferential analysis (Student’s t-test) |

| Ávila-Toscano et al. (2021) | Quantitative Correlational | Scales | Correlational and predictive analysis |

| Riaño-Rodríguez (2024) | Qualitative Descriptive-Interpretative | Interviews, focus groups, observations | Qualitative coding and triangulation |

| Bueno (2021) | Qualitative Theoretical Review | Scientific documents | Argumentative analysis and narrative synthesis |

| Denkci Akkaş et al. (2020) | Qualitative Conceptual Review | Documentary review | Theoretical-interpretative analysis |

| Furlan and Martínez-Santos (2023) | Mixed Quasi-experimental with case study | Questionnaires and interviews | Mixed analysis (qualitative clinical and quantitative) |

| Type of Assessment | Number of Studies | Predominant Emotional Patterns | Representative Authors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional written assessment | 5 | Anticipatory anxiety, tension, frustration, negative automatic thoughts | Bueno (2021); Harley et al. (2021); De la Fuente et al. (2020); Gutiérrez-Vergara et al. (2020); Zambrano-Vélez et al. (2023) |

| Individual oral assessment | 4 | Shame, avoidance, sweating, insecurity, cognitive blocking | Furlan and Martínez-Santos (2023); Abad et al. (2021); Denkci Akkaş et al. (2020); Gao (2024) |

| Foreign language assessment | 3 | Fear of social judgment, language anxiety, muscle rigidity, communicative withdrawal | Denkci Akkaş et al. (2020); Abad et al. (2021); Gao (2024) |

| Digital/computer-based assessment | 2 | Emotional regulation, reduced anxiety, greater control and enjoyment | Harley et al. (2021); Gao (2024) |

| High-stakes standardized assessment | 2 | Pressure, hopelessness, severe anxiety, intrusive thoughts | Riaño-Rodríguez (2024); Bueno (2021) |

| Formative/low-stakes assessment | 1 | Emotional security, intrinsic motivation, reduced emotional tension | Gao (2024) |

| Article | Limitation | Impact on Generalization and Comparability |

|---|---|---|

| Ávila-Toscano et al. (2021) | Design: cross-sectional; convenience sampling | Does not allow causal inference, limits generalization, and the explanatory power is low (3–5%). |

| Gutiérrez-Vergara et al. (2020) | Design: observational, cross-sectional | Does not permit causal inferences; experimental designs are needed to validate relationships. |

| Harley et al. (2021) | Design: not an RCT (Randomized Controlled Trial) | Potential confounders cannot be ruled out, so firm causal conclusions are not supported. |

| Gao (2024) | Design: non-experimental; convenience sampling | Does not allow attributing causal effects of AI/ChatGPT on emotions or anxiety. |

| Furlan and Martínez-Santos (2023) | Design: single-case (N = 1); quasi-experimental (pre–post) | Findings are not generalizable and temporal stability is not established. |

| Abad et al. (2021) | Sample and external validity: small case sample in a specific program | Findings are contextual and difficult to extrapolate to other subjects or institutions. |

| De la Fuente et al. (2020) | Sample and external validity: only Spanish universities | Lack of cross-cultural contrast limits generalization and intercultural invariance. |

| Harley et al. (2021) | Sample and external validity: gender imbalance (low n of men) | Gender comparisons require caution and have limited generalizability. |

| Gutiérrez-Vergara et al. (2020) | Sample and external validity: convenience sampling in one degree program and university | Transferability to other programs and institutions is reduced. |

| González-Peralta and Sánchez-Aguilar (2023) | Sample and external validity: mostly male students | Results cannot be confidently extrapolated to female students. |

| Obregón-Cuesta et al. (2022) | Sample and external validity: reported difficulty generalizing | Population and ecological external validity of the instrument is compromised. |

| Riegel and Evans (2021) | Sample and external validity: convenience sampling with low attendance (~25%) | The sample may be unrepresentative, introducing selection bias. |

| Ávila-Toscano et al. (2021) | Instrumentation and data collection: self-reports; low situational specificity | Lack of situational precision hinders replication and cross-context comparisons. |

| Furlan and Martínez-Santos (2023) | Instrumentation and data collection: self-reports/interviews | Recall bias may be present; observational data are needed to corroborate findings. |

| Gutiérrez-Vergara et al. (2020) | Instrumentation and data collection: long questionnaire (69 items) | Length-related fatigue may bias responses and affect measurement validity. |

| Harley et al. (2021) | Instrumentation and data collection: low internal consistency for anger subscales (discarded) | Discarding anger subscales leaves the negative emotional spectrum undercovered and limits comparability. |

| Riegel and Evans (2021) | Instrumentation and data collection: questionable consistency (shame/anger); no temporal phases | Internal validity is affected and the temporal dynamics proposed by CVT (Control–Value Theory) are not examined. |

| González-Peralta and Sánchez-Aguilar (2023) | Instrumentation and data collection: teacher administered the oral test and the questionnaire | The dual teacher–evaluator role may bias students’ responses. |

| Denkci Akkaş et al. (2020) | Instrumentation and data collection: lack of consensus and adequate tools | The lack of consensus and robust instruments reduces comparability and the strength of findings. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aristizábal Gómez, Y.M.; Jiménez Sierra, Á.A.; Ortega Iglesias, J.M. Students’ Emotions Toward Assessments: A Systematic Review. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 652. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14110652

Aristizábal Gómez YM, Jiménez Sierra ÁA, Ortega Iglesias JM. Students’ Emotions Toward Assessments: A Systematic Review. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(11):652. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14110652

Chicago/Turabian StyleAristizábal Gómez, Yenny Marcela, Ángel Alfonso Jiménez Sierra, and Jorge Mario Ortega Iglesias. 2025. "Students’ Emotions Toward Assessments: A Systematic Review" Social Sciences 14, no. 11: 652. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14110652

APA StyleAristizábal Gómez, Y. M., Jiménez Sierra, Á. A., & Ortega Iglesias, J. M. (2025). Students’ Emotions Toward Assessments: A Systematic Review. Social Sciences, 14(11), 652. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14110652