Factors That Affect Refugees’ Perceptions of Mental Health Services in the UK: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Migrants are defined as people who ‘choose to move not because of a direct threat of persecution or death, but mainly to improve their lives by finding work, or in some cases for education, family reunion, or other reasons. Unlike refugees who cannot safely return home, migrants face no such impediment to return. If they choose to return home, they will continue to receive the protection of their government.’ (UNHCR 2015, p. 1).

- Persons seeking asylum (often termed asylum-seekers) are regarded as individuals who have sought international protection and whose claims for refugee status (as defined by the UN Refugee Convention) have not yet been determined. Since March 2013, the UK Home Office Immigration Enforcement and Visas and Immigration directorates have controlled asylum administration. According to Owers (2003), individuals may apply for asylum under the Refugee Convention, the European Convention of Human Rights 1953, or the Human Rights Act 1998.

- A Refugee is a person who ‘…owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reason of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion1, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it.’ (Article 1A(2) UNHCR 1951, p. 14). What is commonly referred to as refugee status or ‘legitimate refugee’ (see Kirkwood et al. 2016) applies to those ‘whose asylum application has been successful and who is allowed to stay in another country having proved [a ‘well-founded fear’] they would face persecution back home’ (Refugee Council 2005, p. 1). A person who has refugee status under the Refugee Convention in the UK is given five years leave to remain as a refugee. They can then apply for indefinite leave to remain (generally referred to as ILR or ‘settlement’), gaining the right to live, study, and work in the UK permanently. After one year, they are eligible to apply for British citizenship. It is this latter group who was the focus of our systematic review.

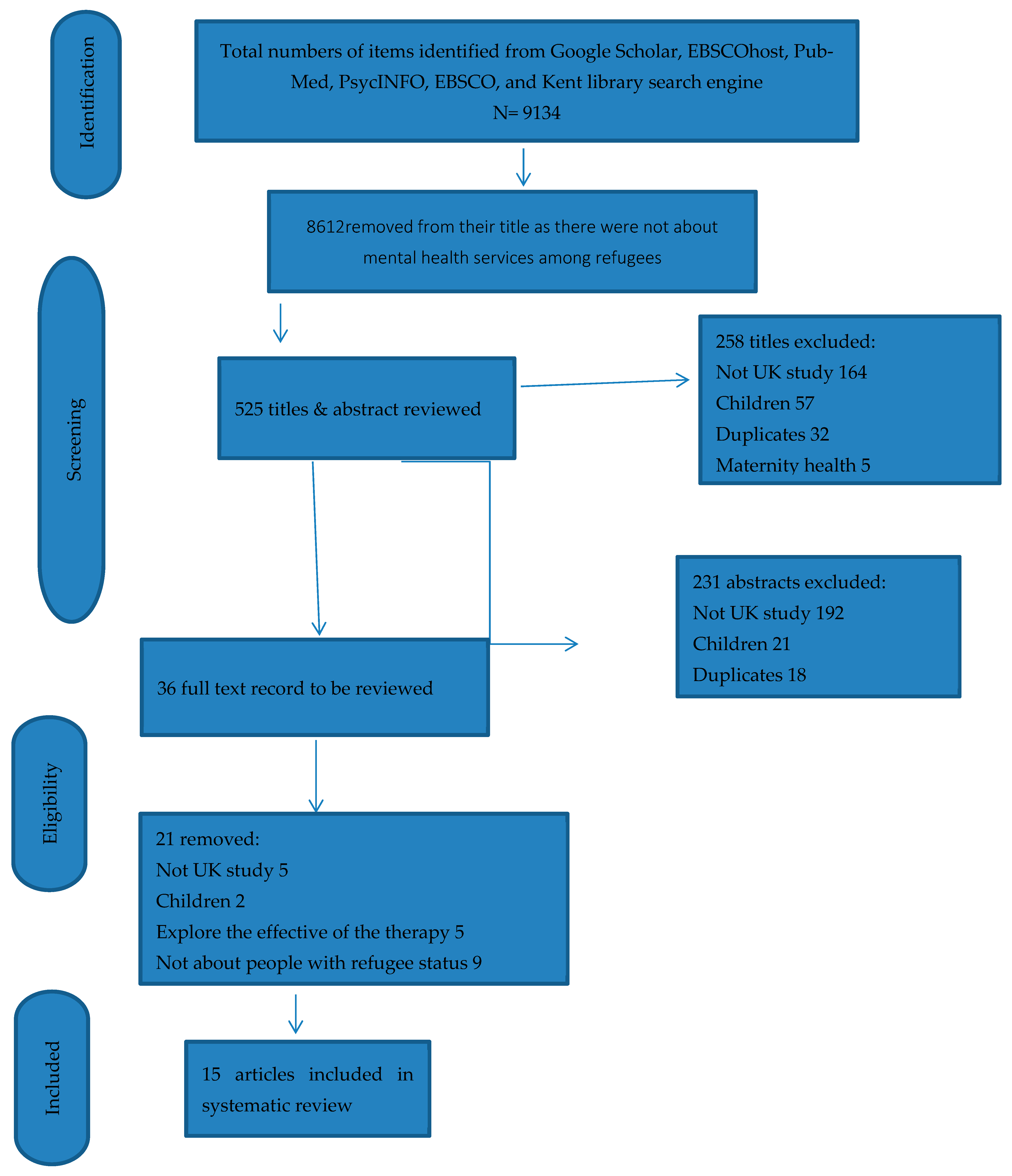

2. Method

- Empirical studies about mental health services for adult refugees with mental health problems and/or post-traumatic stress disorders (PTSDs).

- UK articles published from 2000 to 2024.

- Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods studies.

- Children and older (over 65 years) refugees; more than two-thirds of refugees arriving in the UK are over 18 years and less than 65 years (UNHCR 2022).

- Non-UK studies.

- Articles not written in English.

- Articles published before 2000.

- Non-empirical articles

2.1. Screening

2.2. Data Extraction

2.3. Quality Appraisal

2.4. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence of Psychological Disorders

3.2. Factors Which May Affect Individuals’ Access to Mental Health Services

3.2.1. Theme One: Stigma and Cultural Beliefs About Mental Health Problems

And in Linney et al. (2020, p. 8), whose participants demonstrated how cultural stigma generalizes all forms of mental health problems under one negative label:Back in Syria, people are used to or have the assumption that people who go to psychiatrists have something wrong in their brains, crazy or something.(Participant 9, man)

Other cultures, such as Ethiopian, attributed mental health problems to supernatural or psychosocial causes:Crazy person is crazy person. It doesn’t differentiate—whether it is depression or schizophrenia, it is all the same.(Participant 2, Somali community, UK).

Such closely held values meant that those within the group who were suffering from mental health problems avoided services for fear of being stigmatized by their own communities, as exemplified by the following quote from Paudyal et al. (2021, p. 5):…when someone is depressed in Ethiopia, people say it is an illness caused by Satan.(070 male: 206) Papadopoulos et al. (2004, p. 66)

Similarly, in Palmer and Ward’s (2007) study, two participants said:[…] so the majority of Syrian people are coy of going to the doctor or are not used to this habit, because we don’t have something like that in Syria.(Participant 9, man).

…If someone is stressed, they say [In Ethiopia] ‘Waa waa she’ which means mad. It is quite extreme, there is nothing in between. Stress is less than mad but Somalians talk about being mad.(Somali male, p. 205).

The cultural stigmatization of mental health problems was also a feature of Linney et al.’s (2020, p. 8) study:Inside Somalia people are crazy but they don’t have depression. They (Somali community) didn’t know about depression….I didn’t want to publicize. Depression doesn’t mean anything in Somalia.(Somali male, p. 205).

It’s embarrassing for the families to admit we need help.(Male, FG2, P4).

There are so many people amongst Somali community, it’s a really big taboo subject.(Female, FG1, P3)

Any news that you hear about the country, whether it’s small or big news, it hurts and disturbs the person’s mental state, so you fine us happy for their happiness and sad for their sadness or their suffering.(Participant 8, man; p. 3)

If a person could see his children…like for one of our children to come, we probably would not need a psychiatric doctor…you know? Isn’t this, right?.(Participant 5, woman; p. 3)

Subtheme 2. Lack of trust in UK mental health services and reliance on traditional healers: helped perpetuate refugees’ negative beliefs that they could be helped psychologically. Although Linney et al. (2020, p. 9) reported that women in their sample were more likely to trust UK health services than men, one female participant stating:It is necessary to resort to psychiatric medicine…psychiatry is a normal thing and healthy […] we have a misconception about it likes it’s for crazy people or so…no, no. On the contrary, it’s something healthy and a person must resort to it whenever he feels the need to speak to someone.(Participant 7, man).

We don’t have, not that many barriers affecting with the health services. Whatever the problem we have in mind, the first person to contact will always be the GP.(Female, FG3, P2).

No one would understand what we went through, and the situation like you would…who did not witness it won’t sympathize, yes, so it’s hard for me to go and explain my mental status to a doctor, it’s better to explain to God.(Participant 11, man) (Paudyal et al. 2021, p. 5)

This meant that in the eyes of many refugees, there was no need for mental health services offered by the UK, with a Somali participant in Linney et al.’s (2020, p. 8) study stating:There are also non-religious ceremonies, like the Saar ceremony used in Somalia or the rituals used by the Poosary spiritual healer amongst Tamils, in which the sufferer must dance and sing out the spirit or djinn inside them. Both the Sheikhs (Somalia) and Hojas (Turkey), who use the Quran against evil spirits, can be found in the UK.

Similarly, Nyiri and Eling (2012, p. 600) stated that one participant at a London clinic expressed that:We felt like NHS do not understand what we want, we sent my [family member] back home and he’s ok, thanks God.(Male, FG2, P4).

Subtheme 3. Bravado. Perhaps as a partial antidote to frustrations of perceiving the UK NHS mental health services as not being appropriate to their needs, refugees reported using a form of bravado—appearing ‘strong’ as a coping strategy—to help reduce their own feelings of anxiety and depression. This was also recognized as a cultural trait in studies, since vulnerability is not always expressed easily within some cultures. For example, in Papadopoulos et al. (2004), one refugee stated:It takes so long to see a doctor, and when you do, they don’t understand what I mean. So why should I go again?.(Participant 3, man)

If you show weakness, people will look down on you. So, I keep everything inside and just pretend I am strong.(Participant, Ethiopian refugee in the UK, p. 67).

My mental state is better when I recite the Quran, I continue to do it, it provides comfort for me…Reciting the Quran is a comfort for me….Sometimes I listen to it on the phone, and this is honestly a comfort for me(Participant 11, man, p. 5)

I go to the sea and sit by the seaside, and I express my concerns to the sea, I speak to it. I go to the park, I try to get away from people(Participant 8, man, p. 5)

When I play my instrument, I feel at peace, I don’t think about my problems.(Ethiopian refugee, man)

The person is his own doctor. Whatever happens to you, support or help, if you were not helping yourself from the inside, you won’t be able to succeed. You must keep combating in this life, there is no other way(Participant 1, woman)

3.2.2. Theme Two: Cultural Barriers

You can’t seek help outside and you don’t know how to approach that person who is not in your language speaking.(Female, FG1, P1) (Linney et al. 2020, p. 9)

I think that’s the biggest thing, the language, because medical terminologies you know are very difficult, especially psychological ones […] the language.(Participant 7, man) (Paudyal et al. 2021, p. 5).

You have to translate pain into another language—sometimes the meaning changes completely.

For the translation I think it’s not very helpful, sadly…I mean every expression or word I give out has a certain feeling to it, and for a translation it might not give out the proper meaning, or it won’t come out the intended way, I believe.(Participant 12, man).

This lack of cultural awareness often led refugees to perceive UK mental health services as alien or unresponsive to their needs, reinforcing stigma and discouraging engagement.“When I talk about my pain, they think it is in my body, but it is in my heart.”(Ethiopian refugee, woman).

3.2.3. Theme Three: Structural Barriers to Accessing Mental Health Care

Nevertheless, a lack of knowledge about how to access mental health systems could thwart access, with some refugees in Linney et al.’s (2020, p. 9) study saying that they did not know their way around the UK health system, one even stating:PS2: I was really getting at the end of my rope. I was, I was tired of, sort of, like fighting to be alive […] I was really, really close to just ending everything.

Another refugee talked about how the GP system worked in the UK to exacerbate their lack of trust:It’s always good to seek help but we don’t know how to and that’s the main thing.(Female, FG1, P2)

Being passed from one unit to another combined with long waiting times before gaining treatment was not an uncommon issue, as a refugee in Nyiri and Eling’s (2012, p. 600) study mentioned:Every time you make an appointment you see a different GP which is a big problem.(Female, FG3, P4)

Similarly, a Somali refugee in McCrone et al.’s (2005, p. 355) study said:Even when we manage to register, it feels like the system is not for us. We are always sent from one place to another.(Participant 4, man).

“Even if you are sick, the system makes you wait and wait. By the time help comes, you feel worse.”(Somali refugee, male participant).

We don’t like the police because they intimidate you, they put you down for no reason and health services same as that.(Male, FG2, P4).

There are not many, there’s nowhere to turn other than locally, apart from going to your doctors which is a part of what we are so afraid of.(Male, FG2, P4).

Your GP who will later on section your driving license for God’s sake if you tell them, you haven’t slept the last few days.(Male, FG2, P4).

They also noted that refugees often relied on informal advice networks for help navigating the NHS:When you go to the doctor, you don’t know who you will see, and they don’t know you or what happened before. It feels like starting again every time.(Participant 8, male).

It’s better to ask another Syrian because they know how to get appointments; the doctors don’t have time,(Participant 5, woman).

Let me give you an example. My family and I myself moved a number of times. It is different when the housing officers said ‘this family moved voluntarily’. I do not move voluntarily and I know a lot of people and a lot of families in different boroughs who change addresses because they have to. I myself did four times within three years until eventually I got a place of my own. And I didn’t mean to move, I hate to move, but I had to.(Male, professional).

4. Discussion

it would make sense if you could talk to some Somali person who could understand you rather than going to your GP.(Male, FG1, P4)

Arafat (2016) argued that it is imperative to acknowledge and understand that the presentation of mental health symptoms may be different across minoritized communities. Community integration, acculturation, and psychological distress are some of the key benefits of increased collaboration. When such interventions are co-produced in participatory research involving refugees and the civil society organizations that support this population, they are naturally culturally responsive and can therefore address issues relative to different ethnic needs during the resettlement process (Mahon 2022).Mental health team to recruit an elderly, an elderly person who understands the culture of the community.(Male, FG2, P3)

Comparison with International Systematic Reviews

5. Policy and Practice Implications for the UK and Recommendations

- Professional, trauma-informed interpreting: There is a need to commission regional pools of professionally trained mental-health interpreters with clear confidentiality protocols, independent of local community pressures (Simkhada et al. 2021; Krystallidou et al. 2024; Summerfield 2003; Vincent et al. 2013).

- Co-locate and integrate access points such as the establishment of one-stop “health and settlement” hubs, which could be co-located with primary care, legal aid signposting, and psychological therapies, in areas of high refugee settlement. This approach is supported by evidence from Canadian and European practice (Thomson et al. 2015; Watters and Ingleby 2004).

- Embed bilingual health navigators/cultural brokers within GP practices serving asylum hotels and dispersal accommodation to accelerate registration and referral (McColl and Johnson 2006; Nyiri and Eling 2012).

- Commission culturally adapted and scalable therapies: Scale TF-CBT/NET groups with adaptations to language, idioms of distress, pacing, and inclusion of family/faith-sensitive social and nature components (Nosè et al. 2017; Vincent et al. 2013).

- Making services visibly safe and stigma-reducing such as by holding sessions in neutral community venues (libraries, faith-neutral centers) and providing groups tailored by language, where relevant, that is mindful of the particular challenges in the UK around privacy and visibility within close communities (Linney et al. 2020; Simkhada et al. 2021).

- Addressing post-migration stressors alongside therapy as “therapy-plus” pathways allows clinicians to trigger rapid practical support for housing, asylum advice, and income insecurity. These factors are repeatedly linked to poorer mental health and disengagement and need to be addressed at the same time as therapy (Carswell et al. 2011; Paudyal et al. 2021; Bogic et al. 2015).

6. Strengthening Generalizability

Limitations

7. Conclusions

Relevance to Clinical Practice

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Full Search Strings and Database Hit Counts

- Google Scholar: “Mental health AND refugee* AND (UK OR ‘United Kingdom’)” → 4337 hits;

- EBSCOhost: “Mental health services AND stigma AND refugee* OR asylum seekers” → 1245 hits;

- PubMed: “Refugee* OR asylum seekers AND PTSD OR post-traumatic stress disorder AND (UK OR Britain)” → 2133 hits;

- PsycINFO: “Refugee* OR asylum seekers AND post-traumatic stress disorders AND (United Kingdom OR UK)” → 876 hits;

- EBSCO: “Mental health care AND refugee* OR asylum seekers” → 543 hits.

| 1 | Note that people who flee their homes due to famine or flooding or environmental disaster are not regarded as fearing persecution for any of the Convention reasons. |

| 2 | The papers we reviewed used a wide range of terms such as mental health needs, conditions, and disorders. Following the preferences of UK charities Mental Health Foundation and Mind as well as recent empirical work by Forrester-Jones et al. (2024), we use the term mental health problems. |

References

- Abbas, Mohammad, Tammam Aloudat, Julia Bartolomei, Manuel Carballo, Sophie Durieux-Paillard, and Laurent Gabus. 2018. Migrant and refugee populations: A public health and policy perspective on a continuing global crisis. Antimicrobial Resistance & Infection Control 7: 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alpak, Gülçin, Asli Unal, Fatma Bulbul, Elif Sagaltici, Ahmet Altindag, and Ayşe Dalkilic. 2015. Post-traumatic stress disorder among Syrian refugees in Turkey: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice 19: 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafat, Nadia. 2016. Language, culture and mental health: A study exploring the role of the transcultural mental health worker in Sheffield, UK. International Journal of Culture and Mental Health 9: 71–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnswell, Ian, Olivia Chantler, and Lily Ah-wan. 2025. The Mental Health of Asylum Seekers and Refugees in the UK, 2025th ed. London: The Mental Health Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Bhui, Kamaldeep, Bina Audini, Sarbjit Singh, Rachel Duffett, and Dinesh Bhugra. 2006. Representation of asylum seekers and refugees among psychiatric inpatients in London. Psychiatric Services 57: 270–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackmore, Ruth, Jacqueline A. Boyle, Mina Fazel, Suhail Ranasinha, Katrina M. Gray, Gabrielle Fitzgerald, and Michelle Gibson-Helm. 2020. The prevalence of mental illness in refugees and asylum seekers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Medicine 17: e1003337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blignault, Ilse, Vittoria Ponzio, Yin Rong, and Maurice Eisenbruch. 2008. A qualitative study of barriers to mental health services utilization among migrants from mainland China in south-east Sydney. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 54: 180–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogic, Marina, Amarachi Njoku, and Stefan Priebe. 2015. Long-term mental health of war refugees: A systematic literature review. BMC International Health and Human Rights 15: 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogic, Marina, Dean Ajdukovic, Steven Bremner, Tanja Franciskovic, Giuseppe M. Galeazzi, Alma Kucukalic, and Stefan Priebe. 2012. Factors associated with mental disorders in long-settled war refugees: Refugees from the former Yugoslavia in Germany, Italy and the UK. The British Journal of Psychiatry 200: 216–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnett, Angela, and Michael Peel. 2001. Asylum seekers and refugees in Britain: Health needs of asylum seekers and refugees. BMJ: British Medical Journal 322: 544–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carswell, Katherine, Paul Blackburn, and Chris Barker. 2011. The relationship between trauma, post-migration problems and the psychological well-being of refugees and asylum seekers. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 57: 107–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Close, Ciaran, Anne Kouvonen, Tania Bosqui, Kalpesh Patel, Dermot O’Reilly, and Michael Donnelly. 2016. The mental health and well-being of first-generation migrants: A systematic-narrative review of reviews. Globalization and Health 12: 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, Tom, Paul M. Jajua, and Nasir Warfa. 2009. Mental health care needs of refugees. Psychiatry 8: 351–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenbruch, Maurice. 1990. The cultural bereavement interview: A new clinical research approach for refugees. Psychiatry 53: 301–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazel, Mina, John Wheeler, and John Danesh. 2005. Prevalence of serious mental disorder in 7000 refugees resettled in western countries: A systematic review. The Lancet 365: 1309–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrester-Jones, Rachel, and Gordon Grant. 1997. Resettlement from Large Psychiatric Hospital to Small Community Residence: One Step to Freedom? Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing Group. [Google Scholar]

- Forrester-Jones, Rachel, Jeremy Dixon, and Beth Jaynes. 2024. Exploring romantic need as part of mental health social care practice. Disability & Society 39: 2611–33. [Google Scholar]

- Forrester-Jones, Rachel, Lisa Dietzfelbinger, David Stedman, and Peter Richmond. 2018. Including the ‘Spiritual’ Within Mental Health Care in the UK, from the Experiences of People with Mental Health Problems. Journal of Religion and Health 57: 384–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frissa, Sally, Stephani L. Hatch, Benedict Gazard, Lucy Goodwin, and Matthew Hotopf. 2013. Mental health outcomes of ethnic minority groups in the UK: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine 43: 371–88. [Google Scholar]

- Giacco, Domenico, and Stefan Priebe. 2018. Mental health care for adult refugees in high-income countries. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences 27: 109–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, Erving. 1963. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. New York: Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Green, Helen, David Sperlinger, and Katherine Carswell. 2012. Too close to home? Experiences of Kurdish refugee interpreters working in UK mental health services. Journal of Mental Health 21: 227–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, Clare, and Carol Maxwell. 2000. A needs assessment in a refugee mental health project in North-East London: Extending the counselling model to community support. Medicine, Conflict and Survival 16: 201–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobbs, Jack, and James Souter. 2020. Asylum, affinity, and cosmopolitan solidarity with refugees. Journal of Social Philosophy 51: 543–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Home Office. 2025. How Many People Claim Asylum in the UK? Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/immigration-system-statistics-year-ending-june-2025/how-many-people-claim-asylum-in-the-uk (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Hsu, Lillian M., Christine A. Davies, and David J. Hansen. 2004. Understanding mental health needs of Southeast Asian refugees: Historical, cultural, and contextual challenges. Clinical Psychology Review 24: 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, Michelle L., and Rachel Forrester-Jones. 2022. Human-Centred Design in UK Asylum Social Protection. Social Sciences 11: 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkwood, Steve, Simon Goodman, Chris McVittie, and Andy McKinlay. 2016. Who Counts as an Asylum-Seeker or Refugee? In The Language of Asylum: Refugees and Discourse. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 78–95. [Google Scholar]

- Krystallidou, Despina, Yasemin Temizoz, Yifan Wang, Jordan Looper, Maria Giani, and Georgia Maria. 2024. Communication in refugee and migrant mental healthcare: A systematic rapid review. Health Policy 139: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Siu S. Y., Belinda J. Asp, and Angela Nickerson. 2016. The relationship between post-migration stress and psychological disorders in refugees and asylum seekers. Current Psychiatry Reports 18: 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberati, Alessandro, Douglas G. Altman, Jennifer Tetzlaff, Cynthia Mulrow, Peter C. Gøtzsche, John P. A Ioannidis, Mike Clarke, P J Devereaux, Jos Kleijnen, and David Moher. 2009. The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Healthcare Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration. BMJ 339: b2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linney, Melanie E., Meng Ye, Sarah Redwood, Zahra Mohamed, Fadumo Farah, Laura Biddle, and Helen Crawley. 2020. “Crazy person is crazy person. It doesn’t differentiate”: An exploration into Somali views of mental health and access to healthcare in an established UK Somali community. International Journal for Equity in Health 19: 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowther-Payne, Katherine, Anastasia Ushakova, Rachel Beckwith, Karen Liberty, Dawn Edge, and Fiona Lobban. 2023. Understanding inequalities in access to adult mental health services in the UK: A systematic mapping review. BMC Health Services Research 23: 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahon, Daniel. 2022. A scoping review of interventions delivered by peers to support the resettlement process of refugees and asylum seekers. Trauma Care 2: 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McColl, Helen, and Sarah Johnson. 2006. Characteristics and needs of asylum seekers and refugees in contact with London community mental health teams: A descriptive investigation. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 41: 789–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrone, Paul, Kamaldeep Bhui, Tom Craig, Shukria Mohamud, Nasir Warfa, Stephen Stansfeld, Graham Thornicroft, and Stephen Curtis. 2005. Mental health needs, service use and costs among Somali refugees in the UK. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 111: 351–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nosè, Massimiliano, Federica Ballette, Isabella Bighelli, Giulia Turrini, Marianna Purgato, and Wietse Tol. 2017. Psychosocial interventions for post-traumatic stress disorder in refugees and asylum seekers resettled in high-income countries: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 12: e0171030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyiri, Peter, and Jane Eling. 2012. A specialist clinic for destitute asylum seekers and refugees in London. The British Journal of General Practice 62: e599–e600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owers, Anna. 2003. The Human Rights Act and refugees in the UK. Humanitarian Practice Network 17: 3. Available online: https://odihpn.org/en/publication/the-human-rights-act-and-refugees-in-the-uk/ (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Palmer, David, and Kim Ward. 2007. ‘Lost’: Listening to the voices and mental health needs of forced migrants in London. Medicine, Conflict and Survival 23: 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadopoulos, Renos, Sarah Lees, and Amanuel Gebrehiwot. 2003. The impact of migration on health beliefs and behaviours: The case of Ethiopian refugees in the UK. Contemporary Nurse 15: 210–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, Renos, Sarah Lees, and Amanuel Gebrehiwot. 2004. Ethiopian refugees in the UK: Migration, adaptation and settlement experiences and their relevance to health. Ethnicity & Health 9: 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudyal, Pramila, Melanie Tattan, and Megan Cooper. 2021. Mental health and well-being of Syrian refugees and their coping mechanisms towards integration in the UK: A qualitative study. BMJ Open 11: e041520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollard, Tess, and Natasha Howard. 2021. Mental healthcare for asylum-seekers and refugees residing in the United Kingdom: A scoping review of policies, barriers, and enablers. International Journal of Mental Health Systems 15: 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reavell, Jennifer, and Qulsom Fazil. 2017. The epidemiology of PTSD and depression in refugee minors who have resettled in developed countries. Journal of Mental Health 26: 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refugee Council. 2005. The Refugee Experience in the UK. London: Refugee Council Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Refugee Council. 2017. Refugees and Asylum Seekers in the UK: Key Facts. London: Refugee Council Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Sah, Komal, Andrew Burgess, and Komal Sah. 2019. “Medicine doesn’t cure my worries”: Understanding the drivers of mental distress in older Nepalese women living in the UK. Global Public Health 14: 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sen, Piyal, Jeevitha Arugnanaseelan, Emma Connell, Cornelius Katona, Ahmed A. Khan, Paul Moran, Katy Robjant, and Andrew Forrester. 2018. Mental health morbidity among people subject to immigration detention in the UK: A feasibility study. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences 27: 628–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, Patricia J., Elizabeth Wieling, Jill Simmelink-McCleary, and Emily Becher. 2015. Beyond stigma: Barriers to discussing mental health in refugee populations. Journal of Loss and Trauma 20: 281–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simkhada, Bindu, Maryam Vahdaninia, Edwin van Teijlingen, and Helen Blunt. 2021. Cultural issues on accessing mental health services in Nepali and Iranian migrants’ communities in the UK. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing 30: 1610–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirriyeh, Rasha, Rebecca Lawton, Paul Gardner, and Gerry Armitage. 2011. Reviewing studies with diverse designs: The development and evaluation of a new tool. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 18: 746–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summerfield, Derek. 2001. The invention of post-traumatic stress disorder and the social usefulness of a psychiatric category. British Medical Journal 322: 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summerfield, Derek. 2003. War, exile, moral knowledge and the limits of psychiatric understanding: A clinical case study of a Bosnian refugee in London. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 49: 264–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, James, and Angela Harden. 2008. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology 8: 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, Mary S., Fatima Chaze, Uma George, and Sepali Guruge. 2015. Improving immigrant populations’ access to mental health services in Canada: A review of barriers and recommendations. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 17: 1895–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, Stuart W., Charles Bowie, Graham Dunn, Lule Shapo, and William Yule. 2003. Mental health of Kosovan Albanian refugees in the UK. The British Journal of Psychiatry 182: 444–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turrini, Giulia, Marianna Purgato, Federica Ballette, Massimiliano Nosè, Giovanni Ostuzzi, and Corrado Barbui. 2019. Common mental disorders in asylum seekers and refugees: Umbrella review of prevalence and intervention studies. International Journal of Mental Health Systems 11: 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UK Government. 2004. Zimbabwe: Human Rights and Governance. London: Foreign and Commonwealth Office. Available online: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200304/cmselect/cmfaff/117/117.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- UNHCR. 1951. Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/1951-refugee-convention.html (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- UNHCR. 2015. Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2015. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/statistics (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- UNHCR. 2022. Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2022. Geneva: UNHCR. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/global-trends-report-2022 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- UNHCR. 2024. Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2024. Geneva: UNHCR. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/global-trends-report-2024 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Vincent, Fiona, Rachel Jenkins, Michael Larkin, and Siobhán Clohessy. 2013. Asylum-seekers’ experiences of trauma-focused cognitive behaviour therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder: A qualitative study. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy 41: 579–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vostanis, Panos. 2014. Refugee children’s mental health needs and barriers to care. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry 19: 105–20. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, Peter William, and Nuni Jorgensen. 2024. UK Immigration Statistics: Annual Review 2024. Oxford: Migration Observatory, University of Oxford. Available online: https://migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/resources/briefings/migration-to-the-uk-asylum/ (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Walther, Livia, Laura M. Fuchs, Jürgen Schupp, and Christian von Scheve. 2020. Living conditions and the mental health and well-being of refugees: Evidence from a large-scale German survey. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 22: 903–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warfa, Nasir, Kamaldeep Bhui, Tom Craig, Stephen Curtis, Shukria Mohamud, Stephen Stansfeld, Paul McCrone, and Graham Thornicroft. 2006. Post-migration geographical mobility, mental health and health service utilisation among Somali refugees in the UK: A qualitative study. Health & Place 12: 503–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watters, Charles, and David Ingleby. 2004. Locations of care: Meeting the mental health and social care needs of refugees in Europe. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 27: 549–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author (Year) | Design | QATSDD % | Quality Category | Key Strengths (High-Scoring Items) | Main Limitations (Lower-Scoring Items) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paudyal et al. (2021) | Qualitative (Syrian refugees) | 76% | High | Clear aims; ethical procedures; strong data collection methods | Limited theoretical framework; small, gender-skewed sample |

| Linney et al. (2020) | Qualitative (community participatory) | 81% | High | Participatory design; strong community engagement | Lack of explicit theoretical underpinning |

| Vincent et al. (2013) | Qualitative (therapy acceptability) | 79% | High | Methodological transparency; ethics clearly addressed | Limited generalizability; small, selective sample |

| Bogic et al. (2012) | Quantitative (epidemiological survey) | 86% | High | Large, representative sample; robust statistical analysis | Limited qualitative insight; cross-sectional design |

| Nyiri and Eling (2012) | Service/clinic description | 48% | Moderate | Practical relevance; service-based insights | Weak methodological detail; limited analysis |

| Green et al. (2012) | Qualitative (Kurdish interpreters) | 74% | Good | Culturally grounded; clear ethical procedures | Small sample; limited triangulation |

| Carswell et al. (2011) | Mixed methods (post-trauma, service use) | 71% | Good | Integration of quantitative and qualitative data | Limited theoretical framework; moderate sample size |

| Palmer and Ward (2007) | Qualitative (forced migrants in London) | 69% | Good | Rich qualitative narratives; clear ethical considerations | Lack of analytic transparency; small scale |

| Warfa et al. (2006) | Qualitative (Somali refugees) | 74% | Good | Cultural contextualization; rich qualitative data | Small, convenience sample; limited theoretical framework |

| McColl and Johnson (2006) | Qualitative (community project) | 67% | Good | Community-based approach; clear aims | Limited analytic rigor; descriptive reporting |

| Papadopoulos et al. (2004) | Mixed methods (Ethiopian refugees) | 74% | Good | Clear link between methods and aims; ethical approval obtained | Limited user involvement; descriptive analysis |

| Papadopoulos et al. (2003) | Mixed methods (Ethiopian refugees) | 69% | Good | Innovative design; culturally relevant findings | Weak theoretical justification; non-random sampling |

| Summerfield (2003) | Clinical case reflection | 52% | Moderate | In-depth clinical insight; contextually rich | Anecdotal; lacks systematic methodology |

| Turner et al. (2003) | Quantitative (Kosovan refugees) | 71% | Good | Large sample; defined variables; ethics stated | Cross-sectional; limited cultural interpretation |

| Harris and Maxwell (2000) | Qualitative needs assessment (London refugee communities) | 72% | Good | Comprehensive community involvement; culturally appropriate model; clear ethical framework | Limited generalizability; small N (71 participants across multiple groups); lacks theoretical depth |

| Article Title | Authors/Year of Publication | Study Location in UK | Aims | Sample Size (Gender) [Age] | Methods | Prevalence of Psychological Disorders | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Qualitative study on mental health and well-being of Syrian refugees, and integration in the UK | (Paudyal et al. 2021) | Southeast England | To investigate the mental well-being of Syrian refugees | 12 (3 women, 9 men) [18–79] | Qualitative in-depth semi-structured interviews | Not stated (for ethical reasons) | Syrian refugees face social integration challenges including accessing mental health services, cultural differences, and stigma around mental health and language. |

| 2. “Crazy person is crazy person. It doesn’t differentiate”: an exploration into Somali views of mental health and access to healthcare in an established UK Somali community | (Linney et al. 2020) | Bristol | To discover UK Somali community beliefs and views about mental health problems, treatment, and access to medical services. | 23 (12 men, 11 women) | Qualitative focus groups | Not stated | Participants discussed their lived experiences of mental health problems in relation to trauma from war and forced migration. Language, waiting times, mistrust of doctors linked to cultural beliefs were barriers to accessing healthcare. |

| 3. Asylum-seekers’ experiences of trauma-focused cognitive behavior therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder: A qualitative study | (Vincent et al. 2013) | England and Wales | To estimate the suitability of Trauma-focused CBT (TFCBT) for asylum seekers/refugees with PTSD | 7 (6 asylum seekers, 1 refugee) | Qualitative semi-structured interviews | Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) | Participants expressed their uncertainty about engaging in trauma-focused CBT (TFCBT); describing the treatment as very challenging, but helpful. Factors impeding uptake of treatment include fear of repatriation. |

| 4. Factors associated with mental disorders in long-settled war refugees: refugees from the former Yugoslavia in Germany, Italy and the UK | (Bogic et al. 2012) | Germany, Italy, and UK (unknown) | To compare mental health problems across similar refugee groups resettled in different countries. | 85 (302 in the UK) [18–65] | Quantitative instruments. | Major depression and anxiety disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) | Sociodemographic traits, war experiences and postmigration stressors are separately linked to mental health problems in long-settled war refugees. |

| 5. A specialist clinic for destitute asylum seekers and refugees in London | (Nyiri and Eling 2012) | Brixton | To examine the challenges faced by asylum seekers and refugees in London in accessing physical and mental health care. | 112 (61 male, 51 female) | Quantitative questionnaire | Depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). | Participants had encountered practical barriers to registering with general practices including reticence to request help, complex physical, psychological and social problems, long process of consultations, and language barriers. |

| 6. Too close to home? Experiences of Kurdish refugee interpreters working in UK mental health services | (Green et al. 2012) | Unknown | To explore experiences of Kurdish refugee interpreters working in mental health services in the UK | (4 male–2 female) | Qualitative (semi-structured interview). | Not stated | Interpreters who were also refugees experienced ambiguous and complicated interactions with other professionals. |

| 7. The relationship between trauma, post-migration problems and the psychological well-being of refugees and asylum seekers | (Carswell et al. 2011) | London | To explore the relationship between mental health problems of refugees and asylum seekers, to trauma, post-migration problems, and social support. | 47 | Quantitative standardized measures | Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). | Clinical services need to respond more holistically to the PTSD and emotional distress of refugees who have suffered trauma and post-migration problems. |

| 8. ‘Lost’: Listening to the voices and mental health needs of forced migrants in London | (Palmer and Ward 2007) | Ten boroughs in London | To explore the opinions of refugees and asylum seekers who have mental health problems | 21 [21–65] | Qualitative semi-structured interviews. | Not stated | Forced migration including deculturation (due to the host country’s alien culture), unemployment, and lack of social support leads to mental health problems. Holistic mental health services that include preventative, practical, and interventions are needed |

| 9. Post-migration geographical mobility, mental health and health service utilization among Somali refugees in the UK: A qualitative study | (Warfa et al. 2006) | East and South London | To investigate the perspectives of Somali refugees on their geographical mobility, the relationship to mental health status. | 21 (12 female–9 male) [19–65] | Focus groups | Depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). | Refugees have trouble accessing adequate mental health care due to being moved from one location to another. There is a need for a national strategy to ensure services meet the needs of transient refugees. |

| 10. Mental health needs, service use and costs among Somali refugees in the UK | (McCrone et al. 2005) | East and South London | To evaluate the mental health needs and service use among Somali refugees living in London. | 143 | Quantitative measures. | Not stated | Uptake of mental health services by Somali refugees is relatively low, reflecting their high geographical mobility, especially in the early part of the asylum seeking process. |

| 11. Ethiopian refugees in the UK: Migration, adaptation and settlement experiences and their relevance to health | (Papadopoulos et al. 2004) | Unknown | To investigate the experiences of migration, among Ethiopian refugees and asylum seekers. | 106 refugees | Qualitative open-ended semi-structured and semi-structured questionnaire. | Not stated | Belief that mental illness is due to supernatural and psychosocial causes. Although participants sought help from general practitioners, language barriers and poor understanding of the healthcare system precluded getting adequate care |

| 12. The impact of migration on health beliefs and behaviors: The case of Ethiopian refugees in the UK | (Papadopoulos et al. 2003) | Unknown | To investigate the migration experiences of Ethiopian refugees in the UK, and the effects on their health views and activities | 106 Ethiopian refugees and asylum seekers | Qualitative semi-structured and semi-structured questionnaire. | Not stated | Mental health services need to be holistic to address all refugees’ needs including physical, mental, spiritual, environmental, and social-cultural. Although acculturation to Western medicine may have happened, Ethiopian beliefs about mental health have evolved over thousands of years within a complex society and are unlikely to disappear—this needs to be understood. |

| 13. War, exile, moral knowledge and the limits of psychiatric understanding: A clinical case study of a Bosnian refugee in London | (Summerfield 2003) | Unknown | A study of a Bosnian refugee, a survivor of war | 1 Bosnian refugee | Case study | Depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) | War victims may need intervention by experts as they try to re-establish their lives and need to be aware of the limitations to recovery techniques. |

| 14. Mental health of Kosovan Albanian refugees in the UK | (Turner et al. 2003) | Unknown | To establish the frequency of mental health problems in Kosovan Albanian refugees in the UK | 842 adults/[38.1] | Quantitative measures | Depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) | Just under half of the sample had a diagnosis of PTSD and less than one-fifth had a major depressive disorder indicating refugee conflict survivor resilience. However, psychosocial interventions are likely to be an important part of treatment programs. |

| 15. A needs assessment in refugee mental health project in northeast London: Extending the counselling model to community support | (Harris and Maxwell 2000) | Waltham Forest | To outline the model of care for refugee mental health needs in Waltham Forest. | 71 refugees | Qualitative needs assessment | Not stated | The main focus of the role of the refugee support psychologist was in empowerment, training, reinforcement of refugee identity, and the supply of a one-to-one counselling/therapy service. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Koja, R.; Oliver, D.; Forrester-Jones, R. Factors That Affect Refugees’ Perceptions of Mental Health Services in the UK: A Systematic Review. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 635. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14110635

Koja R, Oliver D, Forrester-Jones R. Factors That Affect Refugees’ Perceptions of Mental Health Services in the UK: A Systematic Review. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(11):635. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14110635

Chicago/Turabian StyleKoja, Rahaf, David Oliver, and Rachel Forrester-Jones. 2025. "Factors That Affect Refugees’ Perceptions of Mental Health Services in the UK: A Systematic Review" Social Sciences 14, no. 11: 635. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14110635

APA StyleKoja, R., Oliver, D., & Forrester-Jones, R. (2025). Factors That Affect Refugees’ Perceptions of Mental Health Services in the UK: A Systematic Review. Social Sciences, 14(11), 635. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14110635