Addressing the Contradictions of Social Work: Lessons from Critical Realism, the Social Solidarity Economy, and the Hull-House Tradition of Social Work

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Problem: The Two Major Contradictions of Social Work

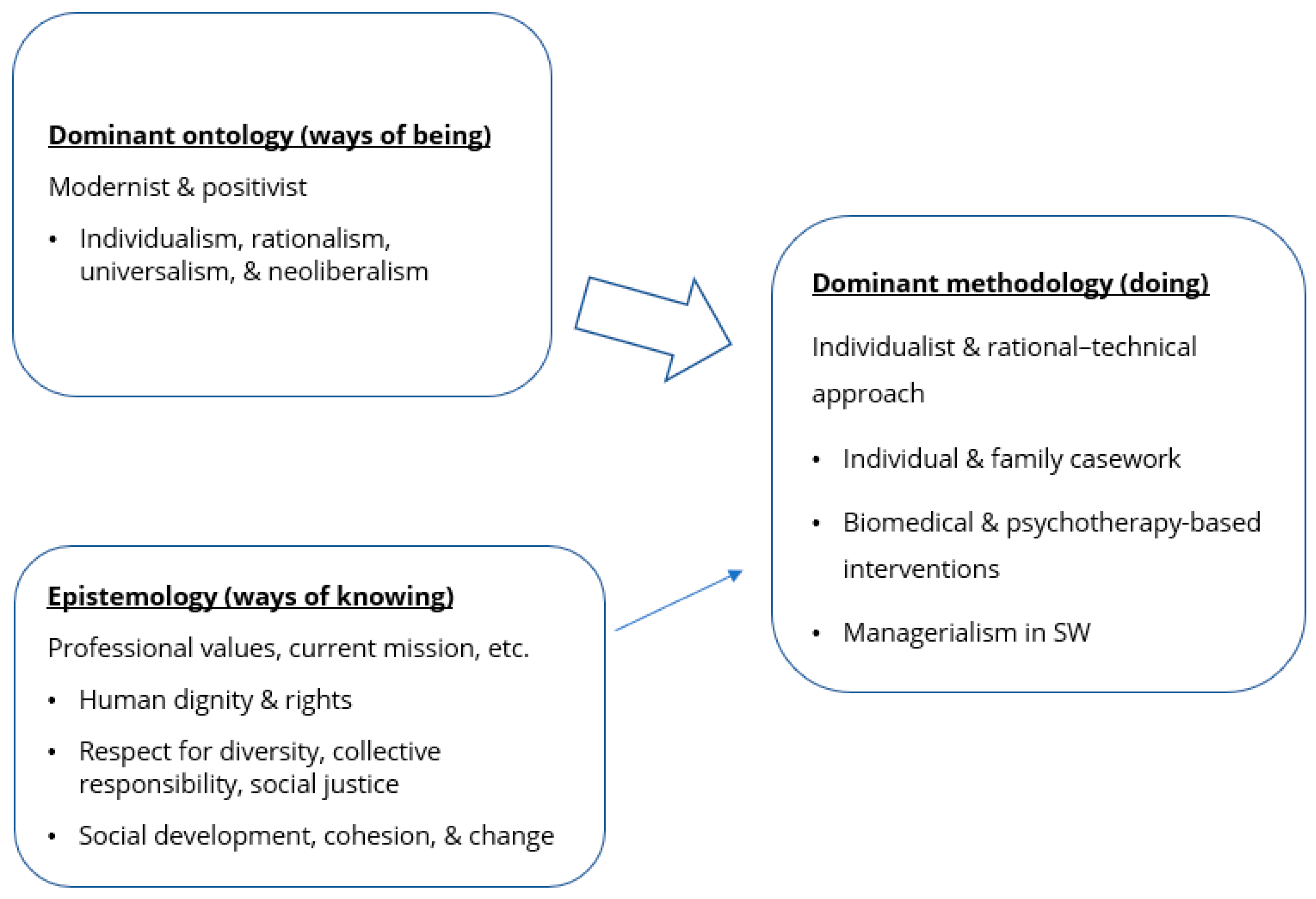

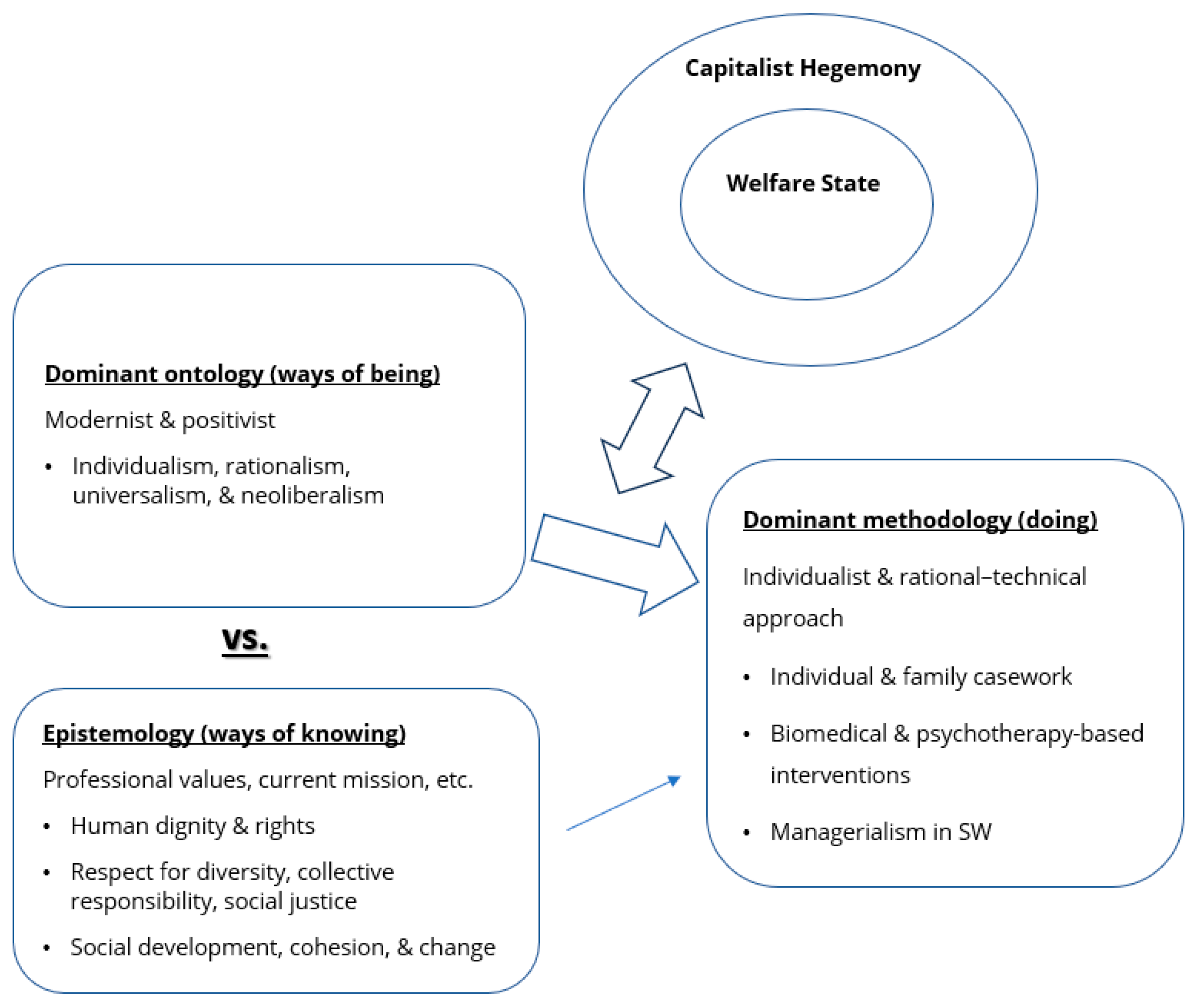

2.1. Inconsistent Ontology, Epistemology, and Methodology

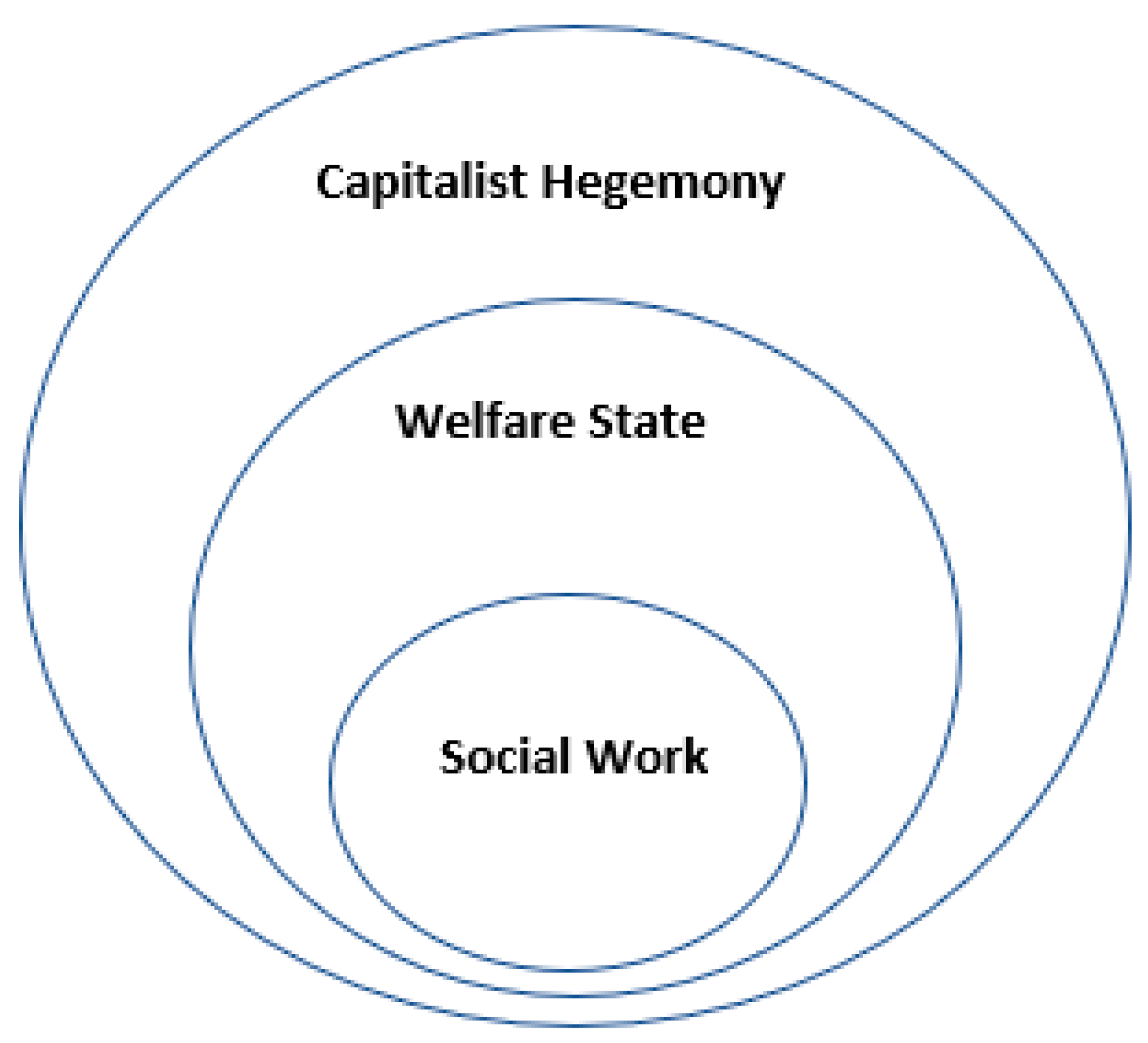

2.2. Co-Dependency with the Capitalist Hegemony

2.3. Consequences for Social Work

3. The Solution: Learning from and Applying Critical Realism, SSE, and the Hull-House Tradition

3.1. Learning from and Applying Critical Realism

3.2. Learning from and Applying SSE and the Hull-House Tradition

3.2.1. Non-Positivist and Non-Individualistic Philosophical Bases

3.2.2. Anti-Capitalist Stance and Response to the Capitalist Hegemony and the Resultant Crises

3.2.3. Experience with the “Immigration Crises”

3.2.4. Innovative and Realistic Solutions to Social Problems

4. Concluding Remarks and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The overall ASTRA research project, which has 15 specific research projects, applies sustainability transition research in SW, tackling the major societal challenge of social exclusion (https://www.jyu.fi/en/research/astra, accessed on 12 July 2025). |

| 2 | We acknowledge the difference between SW in the minority world and the majority world. Yet, SW in the majority world is still greatly influenced by Western theories and models. A good example in this case is SW in Africa, where SW practice and teachings are primarily based on a Eurocentric perspective. |

| 3 | Here we are making a clear distinction between ontology, epistemology, and methodology is in line with Critical Realism’s idea of avoiding the epistemic fallacy, which is common in (social) sciences. According to Critical Realism, ontology (being, which is intransitive) and epistemology (knowledge/knowing, which is transitive) are different things and should not be confused. Confusing the two results in an epistemic fallacy. Critical Realism aspires to solve this problem (Bhaskar 1975, 2016). |

| 4 | “Social democracy tries to establish a compromise between (a) capitalism, and (b) socialist demands for fair wages, good public services, and environmental protections… It resolves the tension [between these two incompatible situations] through imperialism [by appropriating] cheap labour and nature from the global South, from an external “outside”, thus allowing them to offer good wages and public services at home while also maintaining the conditions for capital accumulation… [Therefore,] the core states can have nice human rights at home because they externalize the violence that capitalism requires.” (Hickel 2025, para. 2–6). |

| 5 | Note that such mechanisms [Generative mechanisms/causal mechanisms] could be natural mechanisms (e.g., gravity, photosynthesis, plate tectonics) operating in the physical domain; psychological mechanisms (e.g., conscious and unconscious mechanisms of personality) operating in the mental domain; and social mechanisms (e.g., patriarchy, racism) operating in the social domain (Houston 2001). |

| 6 | This can be connected with individual case work, showing that individualistic methods can still be relevant, especially in combination with group and community work. |

| 7 | See Tadesse and Elsen (2023) for more discussion on Hull-House and the history of SW. |

| 8 | In this case, a third type of SSE could be SSE for marginalized groups (welfare- or handout-based SSE). |

| 9 | It is important to note that, despite being “supported self-help,” the clubs and cooperatives at Hull-House were self-governing (On the Commons 2010). |

| 10 | Jane Addams also had some involvement in the anti-imperialist movement. For instance, she joined the Anti-Imperialist League in 1899 (see Sciancalepore 2024). |

| 11 | Degrowth can be defined as “a planned downscaling of energy and resource use [especially in high-income countries] to bring the economy back into balance with the living world in a safe, just and equitable way” (Hickel 2020). This means achieving a post-capitalist economy, which “ensures human well-being and ecological stability without needing imperialism” (Hickel 2025). |

| 12 | See Tadesse and Elsen (2023) to read the descriptions of the various activities carried out by Hull-House. See also Eberhart (2009) for more on Hull-House’s activities. |

| 13 | Note that degrowth does not mean austerity (Hickel 2020). |

| 14 | Examples of SW programs and practices that have successfully organized SSE/community economy principles can be found in different places. One such example we have observed is the Haus der Solidarität (HdS), which is a social cooperative in Brixen/Bressanone, Italy, that is based on the concept of the settlement house movement and the Hull-House tradition (see their website at: https://www.hds.bz.it/start, accessed on 20 October 2025; see also Tadesse and Elsen 2023). For more examples in the context of Europe, see Matthies et al. (2019) and Matthies et al. (2020). |

| 15 | Such teaching activities already exist in some universities. For example, both the first and second authors of this paper have experience teaching courses about SSE (in the form of social economics or community economy) in social work programs in Germany, at Alice Salomon University of Applied Sciences (ASH Berlin) and Munich University of Applied Sciences (HM), respectively. |

References

- Addams, Jane. 2008. Twenty Years at Hull-House: With Autobiographical Notes. New York: Dover Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Archer, Margaret S. 1995. Realist Social Theory: The Morphogenetic Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- BBC. 2020. Europe’s Migrant Crisis: The Year that Changed a Continent. BBC. August 31. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-53925209 (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Bell, Karen. 2012. Towards a post-conventional philosophical base for social work. British Journal of Social Work 42: 408–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bhaskar, Roy. 1975. A Realist Theory of Science. Leeds: Leeds Books Ltd. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Bhaskar, Roy. 2013. Interview by Russ Volckmann. Youtube. August 6. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8YGHZPg-19k&t=5s (accessed on 26 July 2025).[Green Version]

- Bhaskar, Roy. 2014. Critical Realism—Roy Bhaskar. Interview by Faculti. YouTube. April 28. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TO4FaaVy0Is&t=12s (accessed on 26 July 2025).[Green Version]

- Bhaskar, Roy. 2016. Enlightened Common Sense: The Philosophy of Critical Realism. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Boetto, Heather. 2017. Transformative eco-social model: Challenging modernist assumptions in social work. The British Journal of Social Work 47: 48–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branco, Francisco J. N. 2016. The circle of social reform: The relationship social work—Social policy in Addams and Richmond. European Journal of Social Work 19: 405–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, Ulrich, and Marcus Wissen. 2021. The Imperial Mode of Living: Everyday Life and the Ecological Crisis of Capitalism. New York: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Coates, John. 2003. Ecology and Social Work: Towards a New Paradigm. Halifax: Fernwood Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Dash, Anup. 2016. An epistemological reflection on social and solidarity economy. Forum for Social Economics 45: 61–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhart, Cathy. 2009. Jane Addams:(1860–1935); Sozialarbeit, Sozialpädagogik und Reformpolitik. Bremen: Europäischer Hochschulverlag GmbH & Co. KG. [Google Scholar]

- Elsen, Susanne. 2011. Jane Addams—Demokratie, soziale Teilhabe und Ökosoziale Entwicklung. In Ökosoziale Transformation. Solidarische Ökonomie und die Gestaltung des Gemeinwesens. Perspektiven und Ansätze von Unten. Neu Ulm: AG SPAK Bücher, S., pp. 21–49. [Google Scholar]

- Elsen, Susanne. 2018. Eco-Social Transformation and Community-Based Economy. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Elsen, Susanne. 2023. Social Services and the Social and Solidarity Economy. In Encyclopedia of the Social and Solidarity Economy. Edited by Ilcheong Yi. Cheltenham and Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited in Partnership with UNTFSSE. Available online: https://knowledgehub.unsse.org/knowledge-hub/social-services-and-the-socialand-solidarity-economy/ (accessed on 24 November 2022).

- Franklin, Donna L. 1986. Mary Richmond and Jane Addams: From moral certainty to rational inquiry in social work practice. Social Service Review 60: 504–25. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/30012363 (accessed on 24 November 2022). [CrossRef]

- Gibson-Graham, J. K. 2006. A Postcapitalist Politics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson-Graham, J. K., and Kelly Dombroski, eds. 2020. The Handbook of Diverse Economies. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson-Graham, J. K., Jenny Cameron, and Stephen Healy. 2013. Take Back the Economy: An Ethical Guide for Transforming Our Communities. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhill, Kelly M. 2016. Open arms behind barred doors: Fear, hypocrisy and policy schizophrenia in the European migration crisis. European Law Journal 22: 317–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamington, Maurice. 2022. Jane Addams. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/addams-jane/ (accessed on 24 November 2022).

- Hamington, Maurice. n.d. Jane Addams (1860–1935). Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Available online: https://iep.utm.edu/addamsj/#H4 (accessed on 24 November 2022).

- Healy, Karen. 2014. Social Work Theories in Context: Creating Frameworks for Practice, 2nd ed. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Hickel, Jason. 2020. Less Is More: How Degrowth Will Save the World. London: Penguin Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Hickel, Jason. 2023. The double objective of democratic ecosocialism. Monthly Review 75: 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hickel, Jason. 2025. Social Democracy is Not a Viable Alternative to Capitalism. X. February 16. Available online: https://x.com/jasonhickel/status/1891078438972182898 (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Hickel, Jason, Dyllan Sullivan, and Huzaifa Zoomkawala. 2023. Imperialist appropriation in the world economy: Drain from the global South through unequal exchange, 1990–2015. World Development 165: 106192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossein, Caroline S., ed. 2018. The Black Social Economy in the Americas: Exploring Diverse Community-Based Markets. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Houston, Stan. 2001. Beyond social constructionism: Critical realism and social work. British Journal of Social Work 31: 845–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IFSW. n.d. Global Definition of Social Work. Available online: https://www.ifsw.org/what-is-social-work/global-definition-of-social-work/ (accessed on 24 November 2022).

- Karlsson, Jan Ch. 2020. Refining Archer’s account of agency and organization. Journal of Critical Realism 19: 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malekoff, Andrew, and Catherine P. Papell. 2012. Remembering Hull House, speaking to Jane Addams, and preserving empathy. Social Work with Groups 35: 306–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthies, Aila-Leena, Ingo Stamm, Tuuli Hirvilammi, and Kati Närhi. 2019. Ecosocial Innovations and Their Capacity to Integrate Ecological, Economic and Social Sustainability Transition. Sustainability 11: 2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthies, Aila-Leena, Jef Peeters, Tuuli Hirvilammi, and Ingo Stamm. 2020. Ecosocial innovations enabling social work to promote new forms of sustainable economy. International Journal of Social Welfare 29: 378–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Max-Neef, Manfred. 2017. Development and human needs. In Development Ethics. London: Routledge, pp. 169–86. [Google Scholar]

- Melgar, Patricia, Teresa Plaja, Ariadna Munté, and Gisela Redondo. 2021. Jane Addams, coherence in Uncertain Times: A political entrepreneurship in social work. Social and Education History 10: 362–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, Rodolfo. 2016. Pragmatist epistemology and Jane Addams: Fundamental concepts for the social paradigm of occupational therapy. Occupational Therapy International 23: 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NASW. n.d. Social Work History. Available online: https://www.socialworkers.org/News/Facts/Social-Work-History (accessed on 24 November 2022).

- NASW Foundation. n.d. NASW Pioneers Biography Index: Jane Addams (1860–1935). Available online: https://www.naswfoundation.org/Our-Work/NASW-Social-Work-Pioneers/NASW-Social-Workers-Pioneers-Bio-Index/id/44#:~:text=It%20is%20very%20important%20to,stories%20and%20preserve%20our%20history.&text=The%20life%20and%20work%20of,year%2Dold%20social%20work%20profession (accessed on 24 November 2022).

- Nembhard, Jessica Gordon. 2014. Collective courage: A History of African American Cooperative Economic Thought and Practice. University Park: Penn State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Obeng, James Kutu, and Michael Emru Tadesse. 2024. Exploring the potential of an ecosocial approach for African social work education. In Routledge Handbook of African Social Work Education, 1st ed. Edited by Susan Levy, Uzoma Odera Okoye, Pius T. Tanga and Richard Ingram. London: Routledge, pp. 12–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- On the Commons. 2010. Forging the Urban Commons. May 31. Available online: http://www.onthecommons.org/forging-urbancommons (accessed on 24 November 2022).

- Parton, Nigel, and Patrick O’Byrne. 2000. Constructive Social Work: Towards a New Practice. Basingstoke: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Price, Leigh, and Lee Martin. 2018. Introduction to the special issue: Applied critical realism in the social sciences. Journal of Critical Realism 17: 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciancalepore, Victoria. 2024. Reconsidering Jane Addams: A Portrait of Anti-Imperialism? Jane Adams Papers Project. April 4. Available online: https://janeaddams.ramapo.edu/2024/04/04/displaying-jane/ (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Specht, Harry, and Mark E. Courtney. 1995. Unfaithful Angels: How Social Work has Abandoned Its Mission. New York: Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Spindler, William. 2015. The Year of Europe’s Refugee Crisis. UNHCR. December 8. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/news/stories/2015/12/56ec1ebde/2015-year-europes-refugee-crisis.html (accessed on 24 November 2022).

- Tadesse, Michael Emru, and James Kutu Obeng. 2023. An ecosocial work model for social work education in Africa. African Journal of Social Work 13: 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, Michael Emru, and Susane Elsen. 2023. The Social Solidarity Economy and the Hull-House Tradition of Social Work: Keys for Unlocking the Potential of Social Work for Sustainable Social Development. Social Sciences 12: 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Example Solutions to Social Problems/Needs Practiced by The Hull-House Tradition & the SSE Of PAD | |

|---|---|

| Hull-House Tradition | SSE of PAD |

| Kindergartens & day nursery | Hometown associations (HTAs) |

| Working People’s Social Science Club | Rotating Savings & Credit Associations (ROSCAs) |

| Hull-House Women’s Club | Accumulating Savings & Credit Associations (ASCAs) |

| Hull-House Boys’ Club | Micro-credit associations |

| Hull-House Men’s Club | Burial societies |

| Public baths | Urban community gardens (commons) |

| Public kitchen & coffee-house | Cooperatives |

| Hull-House Labor Museum | Foundations |

| Chicago Arts & Crafts Society | Social enterprises |

| Employment bureau | Development associations |

| Hull-House Cooperative Coal Association | Professional & occupational associations |

| Housing cooperative for young working women (Jane Club) | Student associations |

| Housing co-ops of young men (Phalanx Club & Culver Club) | Women’s association |

| Trade union-related activities | Anti-Racist & anti-imperialist/anti-colonialist associations |

| Social movements (e.g., anti-WWI movement) | Youth & sports-oriented association |

| SW education & social research | Socio-cultural associations |

| The Hull-House college extension program | Welfare/humanitarian/charitable organizations |

| Vocational training programs | Religion-oriented associations (Mahiber, Dahira) |

| Book lending library | Housing associations |

| Playground | Educational institutions |

| Art & music schools | Health-oriented associations |

| Semi-professional theatre | African–European friendship associations |

| Sports hall & sports teams | Online/internet-based associations |

| Pharmacy | Federations/umbrella organizations |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tadesse, M.E.; Elsen, S. Addressing the Contradictions of Social Work: Lessons from Critical Realism, the Social Solidarity Economy, and the Hull-House Tradition of Social Work. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 630. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14110630

Tadesse ME, Elsen S. Addressing the Contradictions of Social Work: Lessons from Critical Realism, the Social Solidarity Economy, and the Hull-House Tradition of Social Work. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(11):630. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14110630

Chicago/Turabian StyleTadesse, Michael Emru, and Susanne Elsen. 2025. "Addressing the Contradictions of Social Work: Lessons from Critical Realism, the Social Solidarity Economy, and the Hull-House Tradition of Social Work" Social Sciences 14, no. 11: 630. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14110630

APA StyleTadesse, M. E., & Elsen, S. (2025). Addressing the Contradictions of Social Work: Lessons from Critical Realism, the Social Solidarity Economy, and the Hull-House Tradition of Social Work. Social Sciences, 14(11), 630. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14110630