1. Introduction

On 19 December 2019, police officers from the Eagle Crack Squad allegedly tortured Mr. Chima Ikwunador to death and unlawfully inflicted various injuries on Mr. Ifeanyi Onyekwere, Mr. Ogbonna Victor, Mr. Ifeanyi Osuji and Mr. Osaze Friday on Ikokwu Road, Port Harcourt, Rivers State. The police brutality caused an uproar in Rivers State. This led the protesters to label the victims as “the Ikokwu 4”. The victims of the police brutality alleged that the police officers tortured them with a hammer, machetes and a piece of “2-by-2” wood (

Chinedu 2021). It was alleged by the surviving victims that the brutality that they experienced led to the death of Mr. Chima Ikwunado (

Chinedu 2021;

Iheamachor 2020;

Ekang 2020). Chima Ikwunado, the deceased victim of the police brutality, and “the Ikokwu 4” were arrested and allegedly tortured by men of the Eagle Crack Squad at the Mile One Police Station in Port Harcourt after the police accused them of being thieves and cultists. The surviving Ikokwu 4 say Chima died because of the torture inflicted by the officers, led by Sergeant Benson Adetuyi (

Nigeria Info 2020). The police did not substantiate their allegation that the Ikokwu 4 were criminals.

The Ikokwu 4 were traders at the Ikokwu motor vehicle spare parts market in Port Harcourt. The accusation that the victims were criminals surprised their fellow traders at the market. With no substantial evidence to back up their accusation, the police officers were believed to have lied to justify their torture. This enraged the traders and civil society groups in Port Harcourt.

As the news of the torture and the death of one of the Ikokwu 4 traders went viral, traders, activists and civil society groups began to protest in Port Harcourt against police brutality. The 2019 Ikokwu 4 incident led to outrage and protests in Port Harcourt. Protesters called for the arrest of the police officers who perpetrated the torture. The press in Port Harcourt, particularly radio journalists, covered the story and asked questions about police professionalism and the doctrine of due process.

Recent protest movement literature has focused on the impact of digital media in enhancing protests’ participation. Digital media and protest movement literature have offered different accounts of the ways digital media influences the organization of collective action. Findings from these studies highlight that online networks help protesters to join political causes, providing channels and data that help the coordination of protest actions and the creation of deliberative space for people to air their grievances or views and iron out their differences (

Bennett et al. 2014;

Segerberg and Bennett 2011). Another way that online media aid social movements is by spreading excitement which facilitates emotional contagion (

Gerbaudo 2016;

Uwalaka and Nwala 2023a). It has been argued that online social movements are conceived, planned, and organized via digital networks to advocate for a specific outcome (

Uwalaka 2024). The majority of such cases entail countering the mainstream posture and tumbling the hegemonic and bourgeois cultures that the protesters believe to be oppressive (

Uwalaka and Nwala 2023a).

Earlier protest movement studies, such as those regarding the ‘Occupy Nigeria’ protests, #BringBackOurGirls protest, and #socialmediabill protest, have argued that social media platforms were instrumental in their organization (

Akpojivi 2019;

Olaniyan and Akpojiv 2021). The 2020 #EndSARS protests that occurred after the 2019 #Ikokwu4 protest was said to have been impactful due to the innovation and diffusion of social media technologies (

Uwalaka 2023;

Uwalaka and Nwala 2023a). However, one area that has not been fully studied is the impact, or lack thereof, of radio in the organization of protest movements. Much of the research on protest movements overlooks or does not try to evaluate the impact of radio on the organization of protests. This disregards the salience of radio in certain areas of the world, such as Nigeria. For example, the success of Rush Limbaugh, which started in the 1980s, created a whole social movement that changed the tenor of the conservative movement in the US (

Brown 2017). Historically, radio has been useful in the mobilization of protests. An example is the southern textile worker insurgency (

Roscigno 2004;

Roscigno and Danaher 2001). These examples are more about social movements that either took time to build and were not confrontational in the form of protests, or were union-based and well organized in a hierarchical way. This study tests the impact or lack of radio in the planning of a protest movement that was instantaneous and lacking in hierarchical leadership.

While many protest movement studies in Nigeria (

Udenze et al. 2024;

Uwalaka and Nwala 2023a;

Uwalaka et al. 2018) have focused almost exclusively on the impact of social media platforms in the organization of protest movements, these inquiries contend that the mainstream media platforms are stale and ineffective. They claim that the diffusion of social media technologies has rendered mainstream media platforms insignificant in influencing protest movements. However, these inquiries fail to unbundle these media platforms for a more succinct evaluation. These anecdotal illustrations are lacking in evidence which tests the validity of these claims.

This study attempts to unpack the impact of different media platforms in the organization of a protest movement. It examines the influence of different media platforms in contentious politics and solidarity building by evaluating how protesters learned about and planned the 2019 #Ikokwu4 protests in Port Harcourt, Rivers State of Nigeria. This study focuses on the impact of radio in the organization of socio-political protests. This study attempts to answer the following research questions:

To what extent did radio stations and other media platforms influence the organization of the 2019 #Ikokwu protests in Rivers State, Nigeria?

How did the 2019 #Ikokwu4 protesters in Rivers State, Nigeria, document their participation in the protests?

What were the effects of specific media platforms in organizing the 2019 #Ikokwu4 protests in Rivers State, Nigeria?

Radio Market in Nigeria

In many parts of Africa, the unparalleled reach of radio makes it a standout media platform. The reach of radio extends to millions of people without internet access. Radio’s enduring power to educate and inform in everyday life and in emergencies is just as important today as it has always been. Radio educates people in Africa in their native tongues, making it a veritable tool to inform and educate.

Radio continues to have a profound influence around the world. However, its influence in Africa is increasingly becoming greater than in the Global North. As

Brooke (

2024, p. 1) notes, “if it tends to be outshone in the Global North by the more recent innovations of television and digital media, in the South, radio continues to have a dominant presence” particularly in Africa “where it retains its status as the most popular mass media”. The most recently survey of news audiences in Africa by Afrobarometer showed that 68% of Africans source their news from the radio on a daily or weekly basis, while about 53% source their news from television and only 37% source their news from the internet (

Malephane 2022). The importance of radio in Nigeria, and by extension in Africa, is clear and understandable. Radio is the cheapest form of mass media in Nigeria. This means that ordinary Nigerians can afford to follow news events on the radio more so than on any other media platform. Generally, the airing of news- and education-based content via radio offers a unique opportunity for the masses to access information that hitherto would have been the preserve of the rich (

Okpeki et al. 2023). Thus, with a radio set by their side, ordinary Nigerians stay informed about societal happenings.

Radio is the most widely available of all the mass media in Nigeria. Radio sets are of different sizes and prices. They can be very portable and quite inexpensive. They can be carried easily and can be listened to with earphones (

Nwokah et al. 2009). A user can power radio sets with electricity or with batteries. This makes radio suitable for media audiences in countries like Nigeria, with infrequent power supplies. Radio does not run out of data. It reaches the rich and the poor, the educated and the not-so-educated, the young and the old, every group, every region or state, every gender and every ethnicity. Since programs are broadcast in local languages in Nigeria, they build reach and trust. This trust helps radio stations to build a community by encouraging listeners to participate and engage in issues that impact them. These are the reasons radio achieved such enduring popularity.

Despite all these points, radio is still understudied in Africa. As radio’s impact in the Global North begins to wane, scholars have neglected to study its impact in Africa, particularly in Nigeria, where its impact is likely still high. As social movements began to mushroom, scholars in the West looked at them in terms of the diffusion of social media platforms. African scholars following in the research trajectory of their Global North counterparts began to study the influence of social media on protest movements. Little to no studies have critically studied the impact of radio on protest movements. Thus, this study is an attempt at understanding the influence of radio in the organization of protest movements.

2. Radio and Socio-Political Contestations

A survey of protest movement literature will reveal the silence of scholars on the role that radio might play in the organization of protest movements. Recent protest movement studies have examined the impact of social media platforms in the organization of social movements. For example, these studies argue that social media helps protesters to organize the participation in a protest, providing channels and data that help in the coordination of protest actions and in creating deliberative space for the people to air their grievances or views, and iron out their differences (

Segerberg and Bennett 2011;

Enikolopov et al. 2020;

Uwalaka and Nwala 2023b).

Even with this silence, there is evidence that radio is an impactful medium in social movements. For example,

Brown (

2017) highlighted how Rush Limbaugh used radio to change the tenor of the conservative movement in the US. Radio, particularly Black-Focused radio, and was salient to the organization of civil rights movements in New Orleans (

Baptiste 2019). Community radio has been argued as enabling social movements and “service delivery protests” (

Anderson 2017;

Day et al. 2021). This shows that radio, when used right, can serve as a medium to enable collective struggle.

About two decades ago, radio was seen as an important platform for protest movements. Some even declared radio as an instrument of protest (

Bosch 2006). Recently,

Bosch (

2024) returned to study the protest movement and public sphere potential of radio. She argued that SAFM is a space for conflict and contestation and thus constitutes a public sphere. It is in this light that radio and other allied platforms were conceptualized as “nano media” (

Dawson 2012). Radio activists consciously cast radio as an alternative to digital utopianism, promoting an understanding of electronic media that emphasizes the local community rather than a global audience of internet users (

Dunbar-Hester 2014). Here,

Dunbar-Hester (

2014) focuses on how these radio activists impute emancipatory politics to the “old” medium of radio technology by promoting the idea that “micro-radio” broadcasting holds the potential to empower ordinary people at the local community level.

Bonini-Baldini (

2017) recounts the role that radio played in Gezi Park protests of June 2013. The scholar argues that radio has not lost the value that it gained as a tool for political and social change during the twentieth century. He notes that radio has repositioned itself within the changing digital landscape of the twenty-first century, mixing itself with social media to continue to amplify radical political discourses, and networking protesters together. While these studies talk about the organizing power of radio, none of the reviewed studies examined the influence of radio, together with other media platforms, on the organization of a particular protest. Understanding the extent that radio is used amidst other media platforms to learn about, plan, and coordinate a protest movement will improve researchers’ understandings of the salience of radio in the grand scheme of things when it comes to protest planning.

The majority of digital activism studies in Africa and Nigeria also focus on how social media platforms are used for the organization of protest movements. Studies have shown how the appropriation of social media enhanced Nigerian youths’ ability to challenge dominant power groups while making it difficult for the power groups to clamp down on the protesters (

Uwalaka 2020;

Uwalaka and Nwala 2023a;

Uwalaka and Watkins 2018). Other scholars reported how X and Facebook were the foremost platforms used to coordinate the 2020 #EndSARS protests (

Dambo et al. 2021;

Obia 2023;

Udenze et al. 2024;

Uwalaka 2024). However, a few studies, such as

Mare (

2014) and

Bosch (

2024), have examined the salience, or lack thereof, of radio in the organization of protest movements in Africa. In his study,

Mare (

2014) discusses how “radio and television stations have tended to delegitimize activists’ political demand” (p. 322). He noted that this has changed as activists who organized “Occupy Grahamstown” made use of community radio among other media platforms. In the country-by-country analysis, he argued that radio was used in Zimbabwe, Malawi, and Mozambique (

Mare 2014). The reviewed studies did not interrogate the influence of radio in the organization of the protests. This study contributes to the literature in this regard. The study attempts to examine the influence of radio in the organization of a protest movement. It shows the salience of radio, or lack thereof, and its areas of influence, if any. The study will add the needed context to radio as a medium of protest in Nigeria, and will examine how that could be adopted in another context.

Appraising the Logic of Connective and Collective Actions

The theoretical framework underpinning this study is the logic of collective and connective actions. The discussion about the logic that necessitates collective action is one that has evolved as digital technologies have evolved. Collective action refers to action taken together by a group of people whose target is to improve their wellbeing and accomplish a common objective (

Olson 1989). Terms such as ‘self-organizing groups’ and ‘private–public lives’ were used to offset the pitfalls of the collection action theory (

Bimber et al. 2005).

Bennett and Segerberg (

2012,

2013),

Bennett et al. (

2014), and

Segerberg and Bennett (

2011) conceptualized the logic of connective action. They contended that communication, and the means of communication, can facilitate the development of organizational structures. Connective action is a theoretical concept offered by

Bennett and Segerberg (

2012) to understand the transformation of political activism in the age of digital media and networks. This theory explains how political communication is personalized in the social media era, and accounts for the effects of this personalization on newly unfolding forms of social movements. Connective action is the self-motivated sharing of already internalized or personalized ideas, plans, images, and resources with networks of others. This ‘sharing’ may take place on networking sites such as Facebook, or via more public media such as Twitter and YouTube (

Bennett and Segerberg 2012;

Kermani 2025;

Uwalaka 2020).

‘Collective action’ according to them, revolves around social movement organizations, collective repertoire, and conspicuous leadership while ‘connective action’ is facilitated by the sharing of personal action frames, enabled by multiple personal communication technologies (

Bennett and Segerberg 2012, p. 744). They conclude that this communication process delivers a crucial organizational capital that allows multitudes to act together. In this type of protest, it has been argued that there is no need for leadership and formal social movement organizations. Overall, considering the evidence from contemporary studies and the changing pattern of political participation, it would be erroneous to perceive politics and political participation as something that happens only in the political arena; neither does it benefit the research community to see it as ubiquitous (

Marsh and Akram 2015). This means that media hybridity is maybe used to organize protests (

Chadwick 2017). Thus, there is a need to carefully evaluate the relationship between media platforms and the organization of protests. This is the thrust of this study, particularly as it relates to Nigeria. In this study, media platforms, both mainstream and social, were unbundled to test for their impact on the organization of the 2019 #Ikokwu4 protests in Rivers State, Nigeria. Unbundling media platforms will help scholars to empirically measure and compare the impact of each of these media platforms on the organization of protest movements.

3. Materials and Methods

This study reports on a purposive cross-sectional face-to-face, paper-based survey of Port Harcourt residents who participated in the 2019 #Ikokwu4 protests in Port Harcourt, Rivers State of Nigeria. The data was collected between May and July 2023. Due to the protests occurring in 2019, the researchers adopted a snowball sampling approach in which some protesters were initially recruited and these initial protesters then introduced the researchers to other protesters, and encouraged these new sets of protesters to participate in the study (

Bryman 2016). Utilizing snowball sampling was important in this study as the protests happened a few years before the study was commissioned. This method allowed fellow protesters to pitch the research to their comrades, having themselves participated in the survey. These referrals helped the researchers to increase participation.

It took participants about 25 min to complete the survey. The survey comprised 35 questions relating to the participants’ communication behavior during the 2019 #Ikokwu4 protests in Rivers State, Nigeria. The researchers did not inform the participants that they were studying radio. They used an unbundled media use survey, where protesters marked the media that they used to learn about, coordinate, and document their participation during the protest. The researchers used a private space at the Ignatius Ajuru University of Education’s (IAUE) library. The researchers contacted about 40 known protesters that joined the 2019 protest. These protesters were invited to the library. They completed their survey inside the university. The researchers encouraged the protesters to reach out to their friends who participated in the protest. These initial 40 protesters helped the researchers reach an additional 120 protesters, who were encouraged to drop by the IAUE’s library to complete the survey. The researchers then encouraged the 120 protesters to reach out to their friends who were yet to complete the survey. The second batch of protesters helped the researchers to reach another 250 protesters. These 250 protesters were invited by the researchers to take the survey, and 248 of the 250 took the survey. In all, 388 participants returned the survey. However, four of the returned surveys were incomplete and unusable. The researchers were left with 384 completed surveys. Responses from these 384 protesters were used for analysis in this study.

The survey consisted of five sections, including general information, media use, documentation, and media comparison. Common method variance was reduced by mixing positively and negatively worded items in the questionnaire. The negatively worded items were re-coded during the data coding period to make the constructs symmetric, and this procedure satisfied the statistical contention of common methods bias variance. The nerve and resolve required to attend the first day of the protests displays bravery and a commitment to change. This is the reason this study attempts to understand the impact of media choice on the likelihood that respondents would report participating on the first day of the protest, and it was measured as a dichotomous variable (joined the protest on the first day = 1; joined on subsequent days = 0). Media platforms used to learn about and plan the protest were measured using a 4 Likert Scale (1 = did not use, 2 = infrequently used, 3 = moderately used, 4 = used a lot). The researchers asked the protesters, “can you remember how much you used the following media platforms to learn about and plan your participation to the ‘Ikokwu4’ protests?”. The protesters were given the following media choices: SMS, Newspaper, Television, Radio, Face-to-Face, Facebook, YouTube, X, Snapchat, WhatsApp, LinkedIn, and Thread.

The reason for using a media platform to communicate about the protests (Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp, SMS, TV, Radio, Print, etc.) and previous protest experience were measured categorically. Regarding the reason for using a media platform, researchers asked, “can you remember why you used any of these media platforms to communicate about the ‘Ikokwu4’ protests?” and response options included the following: the most informative, most used media, most important media, easy to use, number of users, and other media not available. The media platforms used to learn about and plan the protest, the reason for using a media platform, and media used for documentation were adopted from

Tufekci and Wilson (

2012). Gender was measured dichotomously as 1 = male and 0 = female.

Outside descriptive statistics, binary logistic regression was conducted to examine the connections between media use and joining on the first day of the protests. Although respondents’ overall degree of participation in the protests was not assessed, the researchers were confident that participating on the first day is a crucial indicator. Conventional wisdom suggests that the riskiest kind of dissent is that which fails, and the most dangerous protest is one that is small. Thus, smaller protests have a higher likelihood of being effectively censored, isolated, or repressed by those in power (

Tufekci and Wilson 2012;

Uwalaka et al. 2018). Therefore, high participation levels on the first day are often essential to introduce a large force that eventually results in a protest’s success.

After analyzing the survey data, the researchers conducted ten semi-structured interviews between the 22nd and 26th of September 2025. A mixed methods approach following a QUAN → QUAL explanatory design, or a sequential explanatory mixed methods design, was employed. This design method,

Cresswell (

2008) suggests, is derived from a pragmatic worldview that enables researchers access to a range of methods, worldviews, assumptions, and data collection and analysis forms. In this design, the collection and analysis of the quantitative data were conducted prior to the collection and analysis of the qualitative data (

Cresswell 2008). The researchers used a snowball sampling method to reach out to those who participated in the protest. This means that data from the survey research directly informed the interview data collection process. Emphasis was placed more heavily upon the quantitative data, with the qualitative data supporting and explicating the quantitative data. The purpose of the quantitative method was to examine the extent to which media use impacted how protesters learned about and planned their participation in the 2019 #Ikokwu4 protests in Nigeria.

Thematic and meaning condensation approaches were adopted to make sense of the data. At its essence, the approach rephrases what is said by participants into just a few words of a more succinct nature but in which the meaning is not lost. The purpose is to allow the researcher to go ‘beyond what is directly said to work out structures and relations of meaning not immediately apparent in a text’ (

Kvale 1996). This allowed the researchers to use themes and add subjective interpretations to the data, based on what the meaning was perceived to be from the experience gone through in the interview. See the

Supplementary Materials for the interview protocols and questions as well as some abridged interview transcripts.

5. Discussion

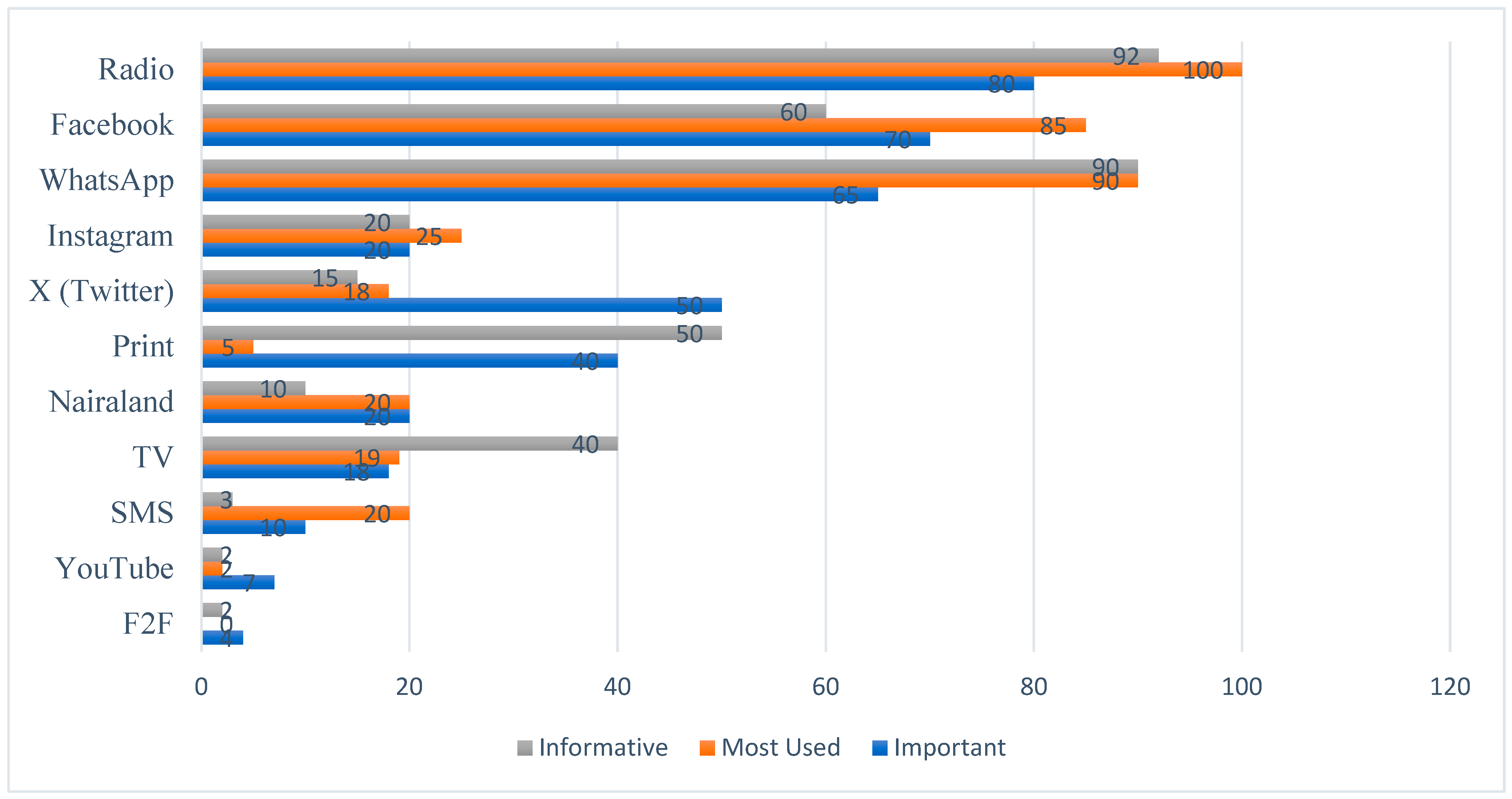

This study examines the influence of different media platforms in the organization of a protest movement. The study focuses on the impact of radio in the organization of socio-political protests. The findings from this study answered the research questions 1, 2 and 3, which were as follows: to what extent did radio stations and other media platforms influence the organization of the 2019 #Ikokwu protests in Rivers State, Nigeria?; how did the 2019 #Ikokwu4 protesters in Rivers State, Nigeria, document their participation in the protests?; and what were the effects of specific media platforms in organizing the 2019 #Ikokwu protests in Rivers State, Nigeria? Results show that radio, as a media platform, and social media platforms were instrumental and influential in the planning and coordination of the 2019 #Ikokwu protests in Nigeria. Radio, Facebook, and WhatsApp were reported to be the most used, informative, and important media platforms for the protesters during the protests. This buttresses the cruciality of hybrid media (

Chadwick 2017). The findings reveal that radio and social media platforms were central during the protests. Our findings show that radio use greatly increased the odds of a protester joining on the first day of the protests. Facebook use was also important regarding whether a respondent reporting joining on the first day of the protests. Both the quantitative and qualitative studies show that social media platforms, such as Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp, as well as radio were instrumental to in protestors learning about, planning and coordinating the 2019 #Ikokwu4 protests in Port Harcourt.

This study highlights that protesters who use radio and Facebook for a protest’s planning and coordination are more likely to report joining on the first day of the protests. The results indicate that previous protest experience is a statistically significant factor of the media used for protest purposes and the day that protesters joined the protests. Gender and education were not significant predictors of protesters reporting joining on the first day of the protests. Findings also show that X use for planning and coordination reduces the chance that a protester will report joining on the first day of the protests. This finding elucidates the importance of studying specific media platforms and assessing these platforms individually. Results from this study show that radio played a key role during the 2019 #Ikokwu4 protests. This finding reveals that radio and Facebook are the media platforms that impacted the coordination of the 2019 #Ikokwu4 protest. This study espouses a fusion of the foundational tenets of the logic of collective and connective actions (

Bennett and Segerberg 2013). This means that regional radio stations and Facebook built enthusiasm that eventuated to a process of emotional contagion through collective and connective repertoires that created propitious psychological conditions (

Gerbaudo 2016) for a mass collective protest action. This indicates that Nigerians innovatively used a fusion of radio and Facebook to bring about enthusiasm that roused people’s emotion to join the protest. This creative and innovative use of radio and Facebook, or hybrid media use (

Chadwick 2017), reduces costs of protest coordination thereby leading to increased protest participation.

This study shows that radio and Facebook played cardinal roles in the planning of the protests. The implication of this is that protesters listened to radio stations around Rivers State to understand what was happening, used social media platforms to identify and publicize targets, to solicit and encourage support, and to recruit and raise funds as a means of promoting their protests (

Adeniyi 2016;

Della Porta and Diani 2015). This finding contrasts with anecdotal claims by some scholars and commentators (

Dambo et al. 2021;

Obia 2023) that X is the foremost platforms for protest organization in Nigeria. For example, some studies have justified their use of posts on X for their data collection by claiming that X “served as the core resource through which #EndSARS protesters organized themselves and coordinated their mass action with over 28 million tweets bearing the hashtag”, and other assertions to that effect (

Adeniyi 2016;

Ojedokun et al. 2021, p. 5). Findings from empirical studies that interfaced with protesters in Nigeria have not corroborated this assertion. For example, starting from the 2012 ‘Occupy Nigeria’ to the 2020 #EndSARS protests, like the findings from this study, results from other studies (

Hari 2014;

Kombol 2014;

Uwalaka et al. 2018) that interfaced with protesters in Nigeria, whether quantitative or qualitative interviews, have uncovered that Facebook and mobile-phone-based applications such as WhatsApp, Badoo, and Eskimi, play a greater role in the organization of the protests than X. This does not mean that X is not a veritable platform for protest coordination. X is important, but protesters in Nigeria do not highlight it as their engine room for protest organization. Results like the above serve as a caution to scholars not to generalize social media use, as individuals and countries use digital platforms differently. These patterns of use may be because of affordability, digital literacy, and cultural alliance.

This study shows the potential of radio as a medium of protests. The researchers asked the protesters to highlight their media use during the protests. This ensured that the protesters were not aware of the focus on radio. The results show that radio is still considered as a protest drum among the participants of this study. The cheapness of acquiring and maintaining a radio indicates that listeners are more likely to own and listen to the radio than any other mass media in Africa. The fact that 68% of surveyed Africans reported radio as their main source of news (

Malephane 2022) lends a weight to the findings of this study.

The findings from this study align with other studies and highlight the role that radio can play during protests. Like

Bonini-Baldini (

2017), this study illustrates how radio mixed itself with Facebook to continue to amplify political discourse and activist movements. Regional radio stations like community radio enable protests movements in Nigeria (

Day et al. 2021). This study shows that radio is arguably one of the instruments of protest movements (

Bosch 2006), and a form of nano media (

Dawson 2012). Like

Mare (

2014) and

Bosch (

2024), radio, particularly regional radio, was used among other media platforms, such as Facebook, to organize the protests. This illustrates the salience of radio as one of the protest drums in Nigeria.

Results from the survey analysis further show that social media platforms were the most used platforms to document protest participation. The production and sharing of videos and pictures of the protests enticed those who previously may not have wanted to join the protests but were convinced to participate. This is because the more videos and images showing the progress of the protest and the common concerns that the protesters are espousing, the more neutral people are tempted to join the protests. Such images show the success of the protests, thereby giving cover to prospective protesters who may be afraid to join the protests. Documentation also helps to stamp out violence against protesters from the government and expose the government when they attempt to muzzle the protesters, as was the case during the 2019 #Ikokwu4 protests in Nigeria. Findings from this study demonstrate and solidify the importance of social media in protest documentation. This finding resonates with findings from other studies (

Tufekci and Wilson 2012;

Uwalaka 2024;

Uwalaka and Nwala 2023a;

Uwalaka et al. 2018) where Facebook and WhatsApp were used by protesters to document their participation.

The 2019 #Ikokwu protesters used different media platforms for different things. For example, protesters reported that Facebook was the media platform where they produced and received documentation relating to the protest the most. This means that participants took and uploaded images and videos of themselves, and were exposed to the videos and images that were uploaded by other protesters, on Facebook. However, radio was ranked as the most used and important media platform in planning and coordinating the protests while print was ranked as one of the most informative media for planning and coordinating the protests. This shows that protesters in Nigeria are media savvy and could chop and change media platforms to fit what they are trying to achieve. The use of different media platforms for different things before and during the protests is a testament to the media literacy of modern protesters. It also buttresses the theoretical underpinnings of the logic of collective and connective actions.

These results highlight the centrality of social media platforms in the documentation of the protests. Along with the increased visibility of social media platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, Thread, X, and YouTube the study shows that protesters are utilizing emerging social media platforms. Radio and social media induce protest activities by reducing the cost of coordination. This shows that as more people use radio and social media platforms, they expose themselves to information that is critical of those in power. This information awakens the participants to protesting conditions they would not ordinarily have assessed as oppressive or corrupt. This study’s results slightly depart from earlier studies. For instance, Facebook was reportedly used to document protesters participating in protests (

Tufekci and Wilson 2012;

Uwalaka 2023;

Uwalaka and Watkins 2018).

Uwalaka and Nwala (

2023a) highlight that WhatsApp was the media platform that protesters used the most to document their participation. Earlier studies on the 2012 ‘Occupy Nigeria’ protests reported Eskimi as the media platform that protesters used to document their participation. This finding implies that Nigerian protesters’ media diet during protests changes. The change appears to be a utility, based on any other thing. The implication is that as technology innovates, there is greater potential that Nigerians will adopt and incorporate such technologies in their protest activities.

The study demonstrates why media platforms should be unbundled and studied to help visualize the impacts and effectiveness of each media platform in protest planning and coordination. When media is unbundled as we have performed here, it uncovers the weakness of certain famous media platforms such as X. This is because X has consistently underperformed in empirical studies that have evaluated the impact of media platforms in the organization of protests. For example, X (then Twitter) was not significant in

Tufekci and Wilson’s (

2012), and

Wilson and Dunn’s (

2011), inquiries about the role of the media during the Egyptians protests. X was also not significant in empirical studies that evaluated the role of different media platforms in the organization of the ‘Occupy Nigeria’ protests (

Hari 2014). This same pattern repeated during the 2020 #EndSARS protests in Nigeria. An earlier study showed that Facebook and WhatsApp are significant in predicting who joins on the first day of the protests (

Uwalaka 2024). This trend continued in our current findings. In this study, Facebook and WhatsApp use are significant predictors for joining the protests and joining on the first day of the protests.

More broadly, this study shows that mainstream media, such as radio in this instance, is still impactful on protest planning and organization. Many scholars have written the obituaries of the mainstream media’s ability to mobilize protests. These noted inabilities of mainstream media are increasingly becoming stale. This is because the mainstream media is increasingly being reportedly used to learn about and plan for protests. This study finds that radio and social media platforms, such as Facebook and WhatsApp, in Nigeria mediated many kinds of ties and brings together individuals, news, information, and social support that is needed to coordinate socio-political contestations. Protesters’ capability to inspire camaraderie via dispersed and loose networks while allowing for solidarity building during the protests demonstrates the personalization of politics, and the appropriation of issues once reserved for ideological groups, drawn together through a shared understanding of the mutual apprehension of police brutality in Nigeria. This resonates and demonstrates the key theoretical underpinnings of connective and collective action. Specifically, we found that radio provides protesters with other avenues to plan and coordinate protest movements.

Although this study shows that radio was used in protest movements, it is important to note that radio could also serve as an instrument for hate and propaganda, particularly in the case of state-controlled broadcasting. While it was earlier argued that Rush Limbuagh stirred a social movement in the Republican Party in the US, it is also important to note that he employed a minority propaganda technique in espousing his political agenda (

Swain 1999). It is also well studied that the misappropriation of radio in Rwanda contributed to the Rwandan genocide (

Kellow and Steeves 1998;

Li 2004;

Straus 2007). Radio Venda has been accused of perpetuating apartheid ideologies during the apartheid regime in South Africa (

Netshivhambe 2025). This shows that radio, like other media platforms, could become an instrument of oppression when used wrongly.

7. Conclusions

This study presents findings regarding how the 2019 #Ikokwu4 protests were organized and documented. This study shows how the fusion of radio and Facebook influenced the organization of the 2019 #Ikokwu4 protests. The point is that, while protests are increasingly personalized and solitary due to advancements in digital technologies, participants are fusing radio with digital media platforms, such as Facebook, for effective protest organization. The study extends the current knowledge of protest movement culture by illuminating the significant role that radio plays, in certain contexts, in the organization of the protests. This contribution underscores the potential of radio in the organization of protests.

This study uncovers elements of both collective and connective actions. Although for the most part, the study confirms the increasing role that Facebook plays in protest organization, the study provides evidence that protests conducted on Instagram, Facebook, and WhatsApp frequently spill over into offline spaces. The study explicates and extends the theorization of the logic of collective and connective actions. It unpacks how the self-organizing and the personalization of protests help metastasize collective and connective actions.

This study highlights the need to unbundle media platforms when studying how such media platforms influence protest movements. The study shows the emancipatory aspects of radio as a protest drum during the 2019 #Ikokwu4 protests in Rivers State. The study illustrates the protest amplification potentials of radio and underscores the importance of radio in the conduct of protests in the regional areas of Nigeria.