1. Introduction

Late in the evening of Friday, 1 December 2023, the United States Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) released a statement on their website that beginning at midnight on December 4, they would be abruptly closing the Lukeville Port of Entry (PoE), a vital crossing linking Sonoyta, Sonora, Mexico, and southern Arizona, USA (

U.S. Customs and Border Patrol 2023). At that time, Authors 1 and 2 were both residing in Ajo, around thirty minutes from the PoE. We, along with many others, did not receive official notice of the announcement until late Saturday afternoon, when it was announced on local radio and in the small regional news outlet, Ajo Copper News. This gap in information sharing left residents on both sides of the border, as well as surrounding communities, with little more than 24 h to prepare for this historic event. For months, hundreds of asylum seekers had been lining up at the PoE, or through gaps in the border fence cut into Organ Pipe National Monument, where Author 1 had been working. The CBP announcement said the PoE closure was meant to “redirect personnel to assist the U.S. Border Patrol with taking migrants into custody,” with the statement also stating the closure was also a response to “apply consequences for unlawful entry… We continue to adjust our operational plans to maximize enforcement efforts against those noncitizens who do not use lawful pathways or processes such as CBP One application and those without a legal basis to remain in the United States” (

U.S. Customs and Border Patrol 2023). Local news outlets framed the closure as necessary to manage rising migrant crossings, narcotrafficking and to maintain a “humane border” (

Castañeda Perez 2023).

However, all three Authors of this paper, all of whom have grown up or are now living in proximity to these areas of increasing border surveillance, regardless of our citizenship status, express concern about what “humane” means in the context of militarized border enforcement. In the rush to close the PoE, this federal decision created consequences that reverberated far beyond the wall itself. According to international law, asylum seekers must cross a border and present themselves at a PoE to submit a viable claim for their asylum case to be heard or be subjected to an “expedited removal” classification that requires a “fear” interview to ensure that their cases are heard promptly (

American Immigration Council 2025). Further, denying asylum seekers one of a safe pathway to asylum claim (a PoE) in a rural area like Lukeville within an area with little to no access to water or sheltermakes their claim with CBP agents upon crossing the U.S. border more essential. The denial of such rights, we argue, is an explicit denial of the established legal framework of “due process” owed to a potential asylum seeker, even one who does not necessarily have the “right” paperwork on hand when they cross into the U.S. (

American Immigration Council 2025).

Our intention in writing this paper is to explore, through real-time analysis, the cascading impact of shifting border enforcement policies on various communities and entities. We demonstrate how the historic Lukeville PoE closure exemplifies multiple ways in which border governance and CBP enforcement decisions, often citing a desire to “maximize enforcement efforts,” typically result in more harm to migrants and adjacent communities (

De León 2015;

Heyman 2021a). The Lukeville PoE closure, therefore, did indeed represent a “crisis,” but not the one being portrayed on national news outlets (

Costa 2022;

Santos 2024). Due to the short time communities like Ajo had to prepare, not only were asylum seekers put into a more dangerous, complicated legal situation that undermined two decades of established legal protocol for asylum seekers, but local humanitarian organizations were overextended, local economies were devastated, binational families were separated, and Indigenous sovereignty in the region was undermined, again.

Furthermore, we assert that long-standing sociopolitical and institutional neglect in the borderlands has shaped the severe and disruptive effects of the 2023 Lukeville Port of Entry (PoE) closure on asylum seekers and local communities alike. Drawing on ethnographic data collected before, during, and after the closure, we conceptualize these effects through two interlinked processes: neglect and disruption. Decades of chronic under-resourcing of state and federal agencies have left both migrants and borderland residents hyper-exposed to cascading crises that undermine dignity and well-being before, during, and after migration (

Anzaldúa 1986;

Heyman 2021b;

Silver and Manzanares 2023). The Lukeville closure exemplified this dynamic: asylum seekers were forced from the legal protections of the PoE into hazardous desert terrain (

Johanson 2020;

Jordan 2024), while bureaucratic tools like the CBP One app deepened exclusion for those without digital literacy or language access, especially Indigenous migrants lacking resources in their native languages (

Murphy et al. 2021). Humanitarian networks scrambled to adjust to shifting Border Patrol directives, local economies dependent on cross-border traffic collapsed, and mixed-status families faced mobility restrictions that disrupted caregiving, schooling, and employment. Indigenous communities, particularly the Tohono O’odham Nation, bore the brunt of these disruptions, revealing the ongoing denial of sovereignty and deepened effects of settler-colonial marginalization under militarized enforcement. Together, neglect and disruption illuminate how the Lukeville closure generated overlapping vulnerabilities that directly harmed asylum seekers while destabilizing community life in ways that extended far beyond the immediate border crossing (

Golash-Boza and Menjívar 2012;

Reineke 2019;

Kravitz 2024).

Guided by ethnographic methods, which include interviews and non-participant observation, volunteering, and community engagement, this paper addresses the central research question: How did the Lukeville PoE closure produce humanitarian, economic, and social disruptions for asylum seekers and borderland stakeholders such as local businesses, residents, and Indigenous communities? To answer this, we first situate the closure within scholarship on border militarization, structural abandonment, sanctioned neglect, and settler-colonial racism, frameworks that clarify how enforcement regimes unevenly distribute vulnerability and precarity. We then provide geographic and historical context for Lukeville before turning to our findings, which we organize across five domains of disruption: asylum access, humanitarian aid, local economies, family separation, and Indigenous sovereignty. Ultimately, our findings demonstrate that the Lukeville closure did not enhance security but instead reproduced a manufactured “crisis” that exacerbated existing neglect, eroded social rights, burdened local communities, and reinforced inequities in border governance. We conclude with policy recommendations rooted in harm reduction, highlighting the urgent stakes of migrant justice, community mobility, and democratic accountability in the U.S. borderlands.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Border Militarization

The Arizona–Sonora border has long been central to U.S. deterrence strategies. The Border Patrol’s “Prevention Through Deterrence” (PTD), announced in 1994 and fully implemented by 1996, deliberately redirected migrants from urban ports of entry into remote desert corridors, particularly those around Lukeville, within Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument (

De León 2015;

Nevins 2002;

Soto 2021;

Stephen 2007). This strategy did little to deter migration but dramatically increased migrant deaths, embedding violence into the very structure of enforcement (

Reineke 2019;

Stewart et al. 2016). Following 9/11, immigration became closely linked to national security, leading to the introduction of new surveillance technologies, increased fencing, and the consolidation of the Immigration and Naturalization Service into the Department of Homeland Security (

Andreas 2012). Legal mechanisms further reinforced this shift: the 2005 REAL ID Act waived environmental and Indigenous protections to expedite wall construction (

Cunningham 2020), while the Secure Fence Act diminished tribal and local authority (

Díaz-Barriga and Dorsey 2020).

These practices criminalize mobility rather than ensuring safety, treating migrants as threats to be contained (

Martinez and Slack 2013). Policies under the Trump administration escalated this trajectory. The Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP) forced asylum seekers to remain in Mexico, exposing them to danger and precarious living conditions (

Kocher 2021), while Title 42 invoked public health to expel asylum seekers without hearings during the COVID-19 pandemic (

Kocher 2021;

Johanson 2020). The Biden administration initially promised change but largely preserved deterrence-based policies, adding new technological barriers through CBP One (

Murphy et al. 2021). In this way, militarization is not a departure from history, but a deepening of the enforcement logics rooted in PTD, demonstrating how contemporary closures, such as Lukeville, build upon decades of deterrence and securitization.

2.2. Structural Abandonment and “Sanctioned” Neglect

Militarization alone does not explain the conditions surrounding Lukeville; it is compounded by structural abandonment, which refers to the systematic withdrawal of state support from those made vulnerable by enforcement regimes (

Reineke 2019). As scholars have long observed, neglect is a defining characteristic of borderland life, shaped by chronic under-resourcing from state and federal levels that leaves communities vulnerable to state power and its consequences (

Anzaldúa 1986;

De León 2015;

Heyman 2021a). Towns such as Ajo and Why, both “unincorporated” areas of Pima County, illustrate this dynamic: with limited government investment, residents have long endured underfunded health systems, restricted services, and reliance on volunteers, grants, and nonprofits to meet basic community needs (

International Sonoran Desert Alliance 2024). Federal policies such as Title 42 and MPP approaches further entrenched a “structural” abandonment by externalizing U.S. obligations, stranding asylum seekers in Mexican border towns, and offloading humanitarian responsibilities onto civil society actors (

Harrison 2025).

This overlap of militarization and abandonment reflects what

Stewart et al. (

2016) refer to as a “geography of sanctioned neglect,” in which state policies deliberately create spaces where protections are suspended and aid is restricted. Residents endure resource scarcity alongside increasing militarization. Other studies have demonstrated that this type of neglect in the borderlands is not incidental but instead structured through deliberate policy choices that permit humanitarian crises or scarcity to unfold and reproduce (

Tasker 2019;

Wong 2023). The Lukeville closure made this intersection starkly visible: by shutting down a vital port of entry, federal authorities effectively sanctioned a “crisis” state for both migrants and residents. Migrants stranded in Sonoyta, Mexico, were left exposed to cartel violence, precarious shelters, and inhumane waiting conditions (

Haro 2023), while Arizona communities such as Ajo experienced severe disruptions to long-established cross-border economies, social and health systems (

Cothran et al. 2012). These conditions embody what

Menjívar and Abrego (

2012) and

Cebulko (

2025) describe as examples of “legal violence,” in which law itself produces harm by stripping access to rights, mobility, and survival, and then delineates these along lines of race, ethnicity, and class. Sanctioned neglect, in the case of Lukeville, bridges militarization and abandonment: enforcement generates the crisis, while withdrawal of support ensures that the “crisis” reproduces in some form and persists.

2.3. Settler Colonial Racism

These dynamics also unfold within a settler-colonial framework that targets Indigenous peoples whose lands long predate the U.S.–Mexico border. Border militarization has disrupted Tohono O’odham sovereignty, restricted access to traditional lands, and endangered sacred sites, one such instance being the desecration of Quitobaquito Springs during wall construction (

Orsi 2023). Such projects reproduce colonial logics that privilege state security over Indigenous rights (

Painter 2021;

Madsen 2024). Policies, MMP, Title 42, and CBP One, have only deepened these patterns of exclusion by shifting the protocols and accessibility of asylum procedures towards exclusion in the name of “security” rather than prioritizing historical commitments to asylum seeker legal rights (

American Immigration Council 2025). Therefore, we saw how Lukeville PoE closure similarly reflects these colonial hierarchies. The Tohono O’odham Nation has consistently opposed fortification measures, citing violations of sovereignty and kinship ties (

Neustadt 2017;

Painter 2021), yet enforcement decisions often proceed without their consent, as was the case with this PoE closure.

By privileging security imperatives, the State has historically neglected (and continues to ignore) its commitments to Indigenous sovereignty and established treaties (

Hu et al. 2024). This historical, intentional neglect of Indigenous governance not only regulated migration but also reproduced settler-colonial dominance through territorial dispossession and the erasure of Indigenous autonomy.

2.4. Geographic Context of the Lukeville PoE

Situating the closure of Lukeville within the other historical contexts of border militarization, structural abandonment, sanctioned neglect, and settler colonial racism clarifies that it is not an isolated event, but rather a continuation of long-standing patterns of exclusion. By the late 20th century, the Prevention Through Deterrence (PTD) model had substantially shifted enforcement to southern Arizona, making it the epicenter of border militarization. Migrant deaths in the Sonoran Desert multiplied under PTD (

De León 2015) while post-9/11 securitization accelerated surveillance and wall construction (

Andreas 2012). Recent policies, have only deepened these patterns of exclusion by shifting the protocols and accessibility of asylum procedures (

Kocher 2021;

Johanson 2020;

Murphy et al. 2021).

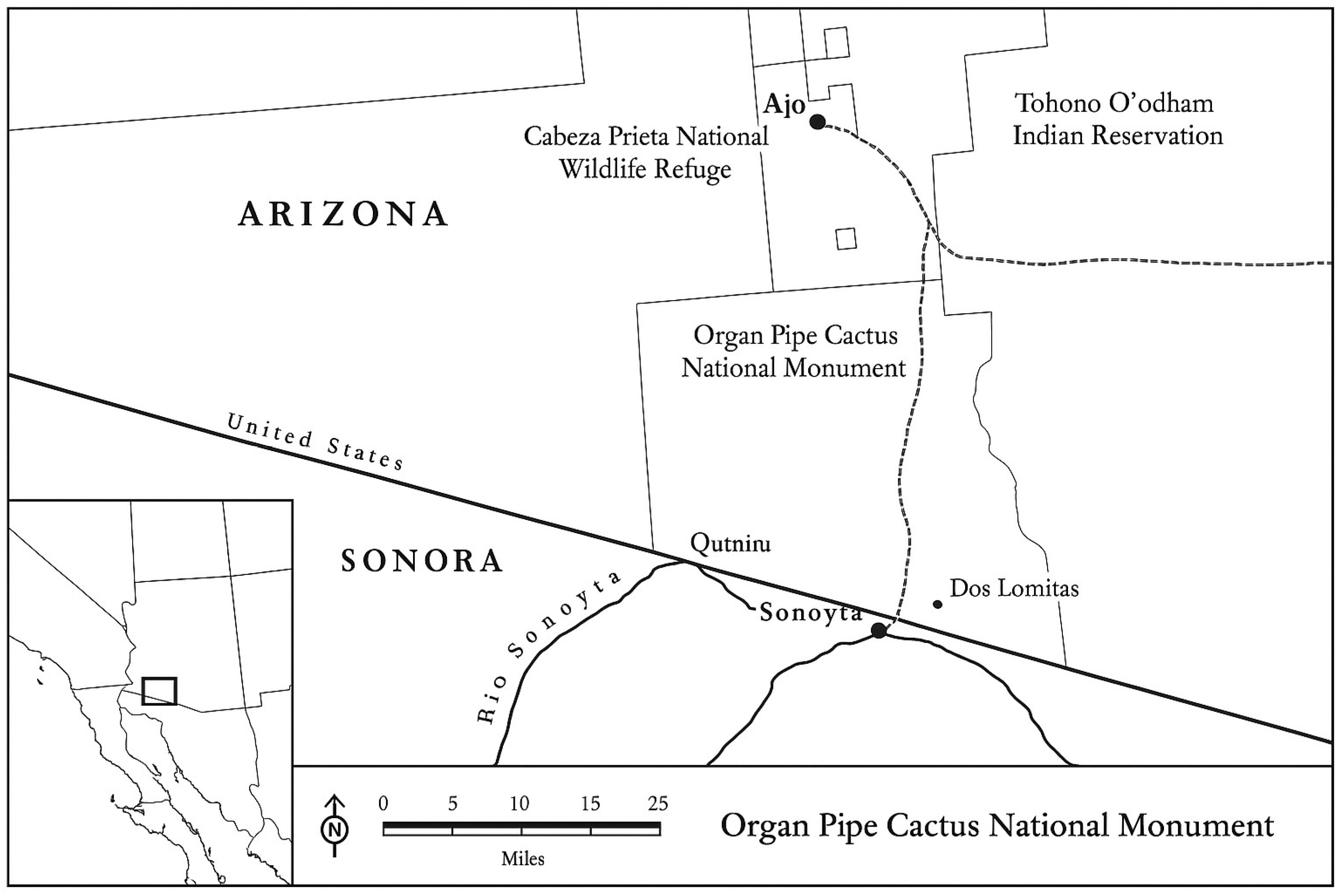

Near Ajo, Why, Organ Pipe National Monument, all the closest communities near the Lukeville PoE, the seasonal population flows, and economic relationships in these areas in southern Arizona and Rocky Point, Sonora. Each winter, these areas near Lukeville experience a surge in part-time residents known as “snowbirds,” who are typically older people from colder U.S. states or Canada who spend the winter months in warmer climates (

Frati 2017). These visitors often use Lukeville to travel to second homes or long-term rentals in Mexico. Blocking this route had ripple effects on tourism and local economies in both southern Arizona and Sonora, intersecting with broader issues of gentrification and displacement. See

Figure 1 below for reference areas in our study of Ajo and Lukeville PoE, located just north of Sonoyta, taken from (

Piekielek 2016):

These histories and contemporary circumstances demonstrate how the sociopolitical geographies of the area around the Lukeville PoE contributed to its closure in December 2023. Below, we discuss the development of the ethnographic project and the methods used to collect, code, and analyze the data during the period of the PoE closure.

3. Methodology

The primary data for this paper were collected by Author 1 during ethnographic research conducted over six months in the areas near Lukeville, between August 2023 and February 2024. Author 1, a white anthropologist specializing in immigration and the U.S.-Mexico border, undertook this research as part of her

Mellon Humanities Postdoctoral Fellowship Program (

2023) with the National Park Service (NPS). The Mellon Humanities Program “places recent humanities PhDs with National Park Service sites and programs across the agency. It aims to advance the National Park Service education mission through new research and study in the humanities. Mellon Fellows work with National Park Service mentors, scholars, and community partners to complete original research projects and develop new interpretive and educational programming” (ibid). Author 1’s fellowship was designed to address “sociocultural and ethnographic research methods to develop a community-based project that connects the public to the richness of the historical experiences of peoples along the trail and interpret how these histories shape contemporary life in the area” (ibid).

Because the fellowship was a federal position, the project required rigorous security clearances and internal authorization for data collection at Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument and surrounding areas. All participants provided informed consent in accordance with Department of the Interior (DOI) and NPS research protocols. This federal clearance also permitted Author 1 to recruit research collaborators with relevant subject-matter expertise. Author 2, a white transmasculine anthropologist and U.S.–Mexican dual citizen, whose research specialties focus on humanitarian aid and environmental anthropology in the Ajo area, joined as a co-researcher, contributing extensively to the interviewing process. Author 3, a Mexican-born graduate student specializing in sociology and immigration law, was later recruited in 2025 to assist with code development and analysis of the paper. All authors are fluent in both English and Spanish, which was essential for work across the borderlands and with this dataset. Other researchers have noted how incorporating diverse researchers with varying expertise and social positionalities contributes to a more holistic and intersectional data collection, coding, and analysis (

Reyes 2020;

Collins 2023).

Between October 2023 and January 2024, Authors 1 and 2 conducted 34 informal and semi-structured interviews. Roughly half took place before the December closure of the Lukeville PoE, with the rest conducted during or shortly after the 31-day shutdown. Several participants engaged in follow-up conversations to clarify or expand on themes as the situation unfolded. Interviews were conducted in both English and Spanish across various settings, including local cafés, libraries, offices, and humanitarian staging areas in Ajo and its surrounding communities. Participants included year-round residents, seasonal visitors such as aforementioned “snowbirds”, business owners, healthcare professionals, humanitarian volunteers, and staff from Organ Pipe National Monument. Interviews conducted before the closure prompted reflection on everyday life near the border, the benefits and challenges of living in the area, and the narratives represented at Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. During and after the closure, conversations shifted to immediate impacts on businesses, emotional well-being, and perceptions of how the closure was managed. Although organized around broad themes of perception, resources, and ideas for change, interviews were intentionally open-ended, allowing participants to narrate experiences in their own words. Alongside interviewing, we conducted sustained participant observation, including site visits to the border wall, monitoring of Customs and Border Protection (CBP) operations, and attendance at town halls, community briefings, and local forums where the closure was discussed. Observations were made at various times of day and documented through detailed field notes. These notes captured what we saw, who we spoke with, and how the physical and social landscape shifted throughout the closure. Authors 1 and 2 also maintained weekly memos that synthesized emerging insights and guided the development of a coding tree.

Interview transcripts, field notes, and observation memos were coded inductively through iterative rounds of open coding. Authors 1 and 2 led the coding process, with Author 3 contributing expertise in migration and human rights to refine the codes and identify broader patterns. They first conducted individual coding and then group coding, addressing any irregularities that arose during the process. Codes were then triangulated across interviews, observations, and memos to strengthen reliability. Given the vulnerability of migrants in transit and the inaccessibility of federal agents during the closure, we did not conduct interviews with either group. As further discussed in the Findings and Limitations section, our analysis triangulates interviews, participant observation, and ethnographic fieldwork to examine how the Lukeville closure disrupted asylum processes, humanitarian aid networks, local economies, families, and Indigenous sovereignty. Below, we outline how the themes of historical neglect manifested in various forms of disruption following the Lukeville PoE closure.

4. Findings on Disruption

Our findings show how disruption reverberated across border life, producing overlapping forms of vulnerability. We begin with the experiences of asylum seekers, then turn to humanitarian aid, local economies, family life, and Indigenous sovereignty.

4.1. Asylum Seekers’ Resource Access

The 2023–2024 closure of the Lukeville Port of Entry (PoE) amplified longstanding narratives conflating migration with criminality (

U.S. Customs and Border Patrol 2023). These narratives justified deterrence-based policies that funneled migrants into remote and dangerous zones such as Organ Pipe National Monument and Cabeza Prieta, where exposure and injury became likely, producing what

Reineke (

2019) and

Stewart et al. (

2016) identify as a “geography of sanctioned neglect.” Field data from both Authors 1 and 2 confirm that the closure heightened this neglect, leaving asylum seekers stranded in desert terrain without consistent access to food, shelter, medical care, or processing.

In pre-closure observations (September–November 2023), Author 1 witnessed asylum seekers waiting multiple times along the Roosevelt Easement in Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. On 5 October 2023, she saw migrants sitting in the open sun without shade or water as trash and human waste accumulated. These conditions echo

De León’s (

2015) “Land of Open Graves,” in which policy creates environments of suffering and death. Several migrants were reported dead or gravely injured during this period (

Daniels 2023). The closure worsened conditions as Border Patrol agents instructed asylum seekers to sit for hours at the base of the border wall, often into the night, even when visibly injured or accompanied by infants without coats or shoes (Author 1 fieldnotes, 15 December 2023).

Further, Author 2’s 6 December 2023, notes capture how abrupt the policy shift was: “Without much warning… both pedestrian entry and the road entry are completely shut down… folks in town say it has come as a surprise, have not yet spoken to businesses or people who would be more impacted, but it already seems cruel to do this during December.” This abrupt closure created a total stoppage of legal crossings, forcing migrants to wait in open-air “processing zones” without basic humanitarian provisions. During December 2023 and January 2024, both Authors observed inconsistent and confusing directives from Border Patrol. Some migrants were instructed to remain at water stations, while others were told to walk deeper into Organ Pipe to locate assistance, leading to disorientation and an increased risk. Migrants were eventually sent to be processed at USBP stations, where earlier in the year, local activists had documented inhumane holding conditions where asylum seekers were held outdoors in extreme temperatures (

Del Bosque 2023). They were then loaded into large white buses borrowed from the prison system and driven through the center of Ajo, with darkened windows that prevented public oversight (Author 1 fieldnotes, 16 December 2023). Please see

Figure 2 below for reference.

These conditions directly contradict the humanitarian standards identified by the

International Rescue Committee (

2024), which stipulate that asylum seekers are entitled to food, shelter, safe areas for children, medical screening, and legal orientation. Instead, Author 2’s December 15 notes documented Humane Borders volunteers distributing donated teddy bears and emergency water along Puerto Blanco Road, a sign of community mobilization in the absence of state-provided aid. Even so, asylum seekers increasingly arrived dehydrated, injured, and traumatized, often after walking for days in freezing winter temperatures (Author 2 fieldnotes, December 18). Overall, in conducting our ethnographic fieldwork and over twenty trips down to the border wall in this time period, we saw how the Lukeville closure created conditions of structural neglect where asylum seekers were deprived of lawful protections and forced to endure degrading circumstances. Federal withdrawal from basic humanitarian obligations deepened the deadly terrain of the Arizona borderlands, confirming that deterrence-oriented enforcement produces not safety, but heightened vulnerability (

Kocher 2021;

Johanson 2020).

4.2. Humanitarian Aid Organizing

During the closure of the Lukeville Port of Entry, humanitarian aid networks took on the responsibility for responding to the immediate needs of asylum seekers. However, their tasks were described by interviewees multiple times as “heavy” and “overwhelming.” Border Patrol offered no food, medical aid, or shelter, forcing groups like Humane Borders (HB), Ajo Samaritans, and No More Deaths to serve as critical infrastructure for survival. In fact, Humane Borders is currently the only humanitarian aid group with a permit to distribute aid near the border wall. During the closure, many HB volunteers found their work disrupted despite the permission to be there. Jim, a yearly snowbird who owns a second home in Ajo and drives for Humane Borders, emphasized the paradox: “We’re the only ones allowed to be out here, but they still treat us like criminals” (Author 1 fieldnotes, 11 December 2023). Other humanitarian volunteers reported hostility and surveillance from Border Patrol agents even as they replenished life-saving water stations. Author 2 observed this atmosphere on December 8, where they encountered renewed hostility towards HB volunteer efforts to direct asylum seekers to CBP agents, writing: “Passed 6 or 7 Border Patrol trucks just in this part of Organ Pipe… CBP people seem stressed, the [Humane Borders volunteers] say, which I can also see.” The enforcement-heavy presence amplified fear among volunteers and residents, confirming

Martinez and Slack’s (

2013) findings that policing landscapes not only target migrants but also criminalize humanitarian action.

Despite these pressures, volunteers sought to uphold dignity for asylum seekers. Author 2’s December 21 field notes describe HB volunteers providing care to asylum seekers with limited resources. Asylum seekers arrived dehydrated and cold, some without shoes, others carrying infants. One Guatemalan father, crying, told Author 1 on Christmas Eve, holding the hand of his wife: “We have been waiting two days here [at the wall]. My little girl is sick, and we had no food until the people [volunteers] gave us food.” His testimony highlights how humanitarian groups were filling a federal void, consistent with

Reineke’s (

2019) concept of the “delegation of care” from the state to everyday volunteers.

The closure also strained humanitarian logistics. Author 2 recorded in their December 17 fieldnotes that No More Deaths requested Ajo Samaritan vehicles to redirect resources to Sasabe, Arizona, another migration funnel in eastern Arizona. This is what

Kravitz (

2024) refers to as “aid triage,” where volunteers must allocate resources across multiple crisis points in a militarized desert, relying solely on one another for support. At the same time, migrants waiting in these zones experienced disorientation as they sought next steps in making their asylum claims. As one Honduran in a group of asylum seekers explained to Author 1 on December 19: “One agent told us to wait here, another said walk down the road [to the other Border Patrol post]. We don’t know who to believe.” Confusion compounded risk, leaving families stranded in freezing night temperatures. The Lukeville closure magnified the contradictions of border enforcement: while the federal government withdrew from humanitarian obligations, grassroots volunteers, under surveillance, criminalization, and material scarcity, ensured that asylum seekers survived. As

Kocher (

2021) and

Chacón (

2021) both argue, deterrence does not produce order or safety; instead, it multiplies sites of abandonment and precarity.

4.3. Impact on Local Economies

The economic consequences of the closure rippled immediately through Ajo, Why, and Sonoyta. The Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy (CEDS), coordinated by the International Sonoran Desert Alliance (ISDA), documents the dependence of local economies on cross-border flows of labor and consumers. The closure validated these vulnerabilities, as restaurants, gas stations, and shops reported sharp losses. Further, interviewees expressed that the inconveniences caused by the closure included additional checkpoints, impossible commute times, and an increased fear among the community, not just to be profiled as a potential undocumented immigrant, but also the closure instilled more fear of immigrants themselves.

Dario, a Mexican American restaurant owner in Ajo, described during his interview the double burden of lost business and stranded workers: “Credit cards were maxed out to cover lack of business… my cook (from Mexico) had to stay with friends in town… other employees chose to stay in Sonoyta.” This reflects earlier closures when revenue drops reached up to 80% (

International Sonoran Desert Alliance 2024). Author 2’s December 11 notes confirm this pattern: “Another restaurant manager said he and staff hit heavy, he’s concerned because half his staff live in Sonoyta… he might shut down if this goes longer than a month.” Other businesses reported some customers, but an overall downturn was evident. We found the example of two coffee shops in town that showcase the duality of employee concerns about the PoE closure below.

A coffee shop near the Ajo Inn reported that they kept some customer traffic because the National Guard members stayed in town. However, the Indigenous workers at this coffee shop described feeling “uneasy” about the situation, mainly out of a nervousness of being profiled by federal and military agents as they went to and from work. “But we gotta keep showing up,” T, one of the workers, shared, citing that he and his family had holiday plans and needed the income (Author 1 fieldnotes, 17 December 2023). Navigating social discomfort or potential surveillance during this unprecedented time of the PoE closure, while attempting to maintain “business as usual,” was not uncommon among fieldwork participants and community members.

In another case, though, employees did not necessarily fear being profiled by state agents, but they were the ones stereotyping migrants. Two employees at another popular coffee shop, owned by the spouse of a prominent border patrol leader, shared their thoughts on the “border crisis” and how it poses an issue. Clara, born and raised in Ajo, comes from a Mexican family. She told Author 2: “They [migrants] are scary,” mentioning that she had seen images online of men at the PoE, and this had informed that feeling. Clara also mentioned later that she felt the political issues at the border were driving snowbirds and other tourists away. Amber, Clara’s white coworker, added in that same conversation her discomfort with asylum seekers’ presence in the area: “They (the immigrants) don’t have our culture. They don’t live like we do.” (Author 2 fieldnotes, 13 December 2023). Both young women’s comments alluded to the fact that they did not fear being profiled like the other coffee shop employees. Instead, they viewed the PoE closure and the migrants that “caused it” as a culprit for the economic hardship the community was enduring. These remarks show how economic hardship blended with racialized or xenophobic views of migration and how they coexist in border communities, where even residents who are often descendants of past migrants, like Clara, are part of marginalizing or scapegoating asylum seekers. Some images Clara and Amber may have seen in news outlets at the time of the closure that could have shaped their discomfort with immigrants and immigrant men can be seen in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 below:

These widespread images, released almost daily throughout the closure, combined with the various concerns in Lukeville-adjacent communities, contributed to the economic concerns. Jean, a white artist with a studio in downtown Ajo, noted in her interview with Author 2 that: “Traffic is way down, fewer tourists, fewer buyers. The closure is hurting us badly.” When asked about why she thought this was the case, Jean noted that many tourists did not want to be inconvenienced by the closure and that “probably, fear” of the migrants themselves could be a factor. At a December 18 mixer, International Sonoran Desert Alliance (ISDA) leaders discussed in their public forum that an estimated 30–45% of seasonal losses would occur, while others reported layoffs at gas stations. Around a public campfire after the event, residents described how anxiety about increased surveillance, family separations, and school delays was layered on top of economic strain (Author 2 fieldnotes, 18 December 2023). Other interview participants echoed this theme.

Jerry, a snowbird, shared a few anecdotes about how closing the PoE had impacted not just his sense of safety and well-being, but that of other residents. First, Jerry shared that the idea of having to make a more extended, potentially more dangerous trip through a port of entry he was unfamiliar with to reach his house in Mexico made him nervous for his safety. Second, they saw the closure as a general inconvenience to everyone living near the PoE, sharing that “Closing the PoE created more serious problems than it addressed.” Ron, a local business owner who lives in Ajo year-round, emphasized in our time together just how important the PoE was to daily life and the cross-border economies on both sides of the wall. “We need the Port of Entry open for goods, family, dental, and health. It is greatly impacting our business and our local community.” Ron’s perception is not unique. The

International Sonoran Desert Alliance (

2024) report, which included data on the PoE closure, also observed that Lukeville’s closure had a multifaceted impact on residents in Ajo and Sonoyta, affecting their access to shopping, kinship networks, dental care, and other health concerns beyond the perceived economic impact. The closure’s timing was also cited by a few interview participants, who felt that the PoE’s closure in December exacerbated economic and social damage, since businesses and community members typically relied on the PoE even more during the holiday season.

Even months after reopening, business owners reported to us that the impacts of the PoE closure were having long-term effects on their businesses and the overall economy (

International Sonoran Desert Alliance 2024). Together, these accounts illustrate how border closures destabilize fragile economies and inflame racialized divisions, while federal agencies frame such disruptions as “security.” As

Díaz-Barriga and Dorsey (

2020) note, enforcement discourses obscure the everyday fragility of border-dependent communities, producing a cycle of economic and social vulnerability. We found this vulnerability also extended into the intimate family lives of those around Lukeville.

4.4. Binational Family Dynamics

For residents of Ajo, Why, and Sonoyta, the closure disrupted not only their daily life economically but also emotionally, fracturing binational family ties. Before the closure, many residents on both sides of the border used the Lukeville PoE daily, with some having immediate family, like spouses and children, whom they commuted home to frequently. Emma, a U.S. citizen married to a Sonoyta resident, described in her interview: “We are not able to travel to see him every week as we did before.” Her children, she explained, were deeply affected by missing weekly visits with their father. Similarly, Areyli, a Mexican national employed in Ajo, noted in her interview how the closure was putting extra stress and pressure on her family: “The reroute through San Luis (another PoE) is a seven-hour round trip. It’s impossible to work and care for my family like this!”

Author 2’s December 18 notes from the ISDA business mixer captured the resonance of these stories: “Comments around the campfire on how people are separated from family, cannot visit Mexico, this is the holiday season, and that is very trying. School kids in Mexico who bus up to the Ajo school district are still being allowed through, but with long delays.” These disruptions highlight how PTD strategies operate as a policy of family separation, not only for asylum seekers but for residents with legal permission to work and binational family ties. The strain also produced humor as a coping mechanism for the frustration. In one interview, Esteban, a Mexican and Indigenous restaurant owner in Ajo, remarked during a visit: “I may as well cross under the fence like everyone else” to see his son and other relatives in Sonoyta (Author 2 fieldnotes, December 21). His comments capture the frustration of residents with multi-hour detours, as unauthorized crossings occurred in full view of the community.

Other residents voiced different contradictions. A white snowbird who did not want any name used to describe herself, but identified as in her 70s, told Author 2 on December 23: “I can’t go see my friends in Sonoyta, but those illegals cross however they please.” Her statement underscores what

Kocher (

2021) identifies as the contradictions of militarized deterrence: binational ties are cherished in local culture yet punished in practice when the “wrong” people engage in them. Ron, a white business owner who frequently crosses through Lukeville to see his wife, however, articulated the broader consequence: “The closure disrupted the way of life here, our families, our work, even our healthcare. It makes no sense.” Such comments illustrate how policies framed as enforcement tools have a profound impact on everyday life. Binational family disruption highlights the core contradiction of border security focused on deterring “illegal” activity: its policies not only hurt migrants’ legally protected claims to seek asylum, but also transnational families who have long held dual citizenship or legal status.

4.5. Indigenous Sovereignty

For the Tohono O’odham Nation, the Lukeville closure was yet another episode in a long history of federal disregard for their sovereignty and way of life. In addition to the history of the Nation’s forced separation from their families and land because of the creation and militarization of the U.S.-Mexico border, violence against the Nation continues because of oversteps from Border Patrol. For example, shortly before Author 1 arrived in Ajo, in May 2023, Border Patrol agents killed O’odham community member Raymond Mattia outside his home, shooting him nine times after he stepped outside with a cell phone attempting to report an undocumented crossing on his land (

Wilson and Lucero 2024). His death was highly protested in Ajo, Why, and on the Tohono O’odham Nation for months, underscoring the racialized violence that frames O’odham experiences with federal enforcement.

It is understandable, then, that Nation Chairman Verlon Jose condemned the Lukeville closure, stating: “Closing a legal PoE, effectively shutting down all legal crossings and significant cross-border activity for an entire region, makes no sense whatsoever” (

David 2023). His words highlight another contradiction in federal enforcement: while the nation’s health, education, and commerce depend on cross-border mobility, CPB decisions undermine these essential functions without any consultation with the tribes. Local testimony further illustrates this impact. Carla, an Indigenous business advisor, explained in her interview: “It has affected [Indigenous] business owners I work with, and I hear from them what they are going through… Our human migration system in this country is dysfunctional.” Her perspective reflects what

Díaz-Barriga and Dorsey (

2020) call “spatialized abandonment,” where Indigenous communities are simultaneously hyper-policed and structurally neglected.

Author 2’s December 18 notes from Why, which sits right at the west entry of the Nation, documenting severe economic losses: “Commerce has gone way down… Why Not gas station is losing money every day, and Granny’s (the restaurant) is struggling.” Maya, a Sonoyta resident with legal U.S. work status, who also holds an Indigenous identity, described: “If I need to go in for medical, I have to go two hours out of my way. Plus, it takes another 2 h to reach my destination… Should I climb the wall daily to go to work, or should I just freely cross like they did?” Her rhetorical question underscores how authorized workers were immobilized alongside unauthorized migrants, collapsing distinctions that policy, like a PoE closure, is purported to enforce.

For Indigenous residents living in the area, whose lands and kin are divided by the border wall, the Lukeville closure deepened what

Boyce (

2019) calls the “neoliberal logic” of enforcement infrastructures, including walls, checkpoints, citizenship proved via physical pieces of paper, and electronic systems like CBP One, which erode sovereignty, obstruct mobility, and criminalize everyday life for Indigenous people. As one O’odham elder summarized in a community meeting Author 2 attended on 4 January 2024: “The border has cut through our land for generations. They closed the gate and told us it’s for our safety. Whose safety?” Like the presence of Border Patrol in Indigenous communities, associated with violent incidents, the PoE closure only intensified existing issues while using the cover of safety and protection, leaving communities impacted with more questions than answers, more uncertainty rather than clear direction or safety.

5. Discussion

The closure of the Lukeville Port of Entry (PoE) presents a stark example of how federal enforcement decisions intentionally create neglect and foster conditions of harm under the guise of national security. With very short notice (less than one business day), federal officials suspended legal entry without providing alternative safe pathways, not only failing to deter migration but also generating a predictable humanitarian crisis, rather than upholding obligations under the 1980 Refugee Act and international frameworks such as the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol, enforcement practices actively undermined them (

American Immigration Council 2025). Authors 1 and 2 witnessed migrants left in freezing conditions without shelter, families were separated through arbitrary enforcement, and asylum seekers were denied lawful access to protection, amounting to violations of fundamental human rights to safety, family unity, and due process.

Our findings on the various elements of disruption also demonstrate that the Lukeville closure was not an isolated administrative measure, but part of a broader ideological project rooted in PTD governance strategies that have reverberating consequences. The closure was accompanied by disruptions to humanitarian aid networks, leaving underfunded nonprofits and volunteers to shoulder life-saving responsibilities (

Reineke 2019;

Harrison 2025;

Kravitz 2024). Organizations such as local businesses like ISDA, along with humanitarian aid groups, filled gaps left by the state. These interventions, while vital, exposed the structural outsourcing of humanitarian obligations, in which community infrastructure and fragile networks of care were compelled to manage crises manufactured by the federal government itself. Such dynamics mirror neoliberal models of governance in which surveillance expands while care is externalized to overstretched institutions.

The closure also profoundly destabilized local and binational life. Residents and workers endured dangerous seven-hour detours or prolonged family separations, and healthcare, employment, and economic stability were directly compromised. These experiences blur the supposed binary between someone “undocumented” with papers and “citizen,” showing that border enforcement undermines civic infrastructure and disrupts communities more broadly (

Martinez and Slack 2013). Echoing critiques by

Bush-Joseph (

2024) and

Flores-Gonzalez et al. (

2024), the Lukeville closure can be read as a performative display of state control amid political pressure from right-wing media and populist politicians, racializing asylum seekers and citizens alike (

Trump 2018;

Miroff 2023;

Martin 2024). Such spectacle ignored structural drivers of migration, including persecution, violence, and climate displacement, while criminalizing asylum seekers for exercising their rights to claim asylum (

Johanson 2020).

For Indigenous communities, the closure compounded long histories of settler-colonial racism and disregard for sovereignty. The lack of consultation with the Tohono O’odham Nation, along with the militarization of sacred lands like Quitobaquito Springs, highlights how enforcement continues to override treaty rights and mobility (

Painter 2021;

Tasker 2019). Testimonies from O’odham leaders and Indigenous community members illustrate how restricted access to healthcare, commerce, and education represents yet another iteration of dispossession and structural abandonment. Such erasures reflect what

Díaz-Barriga and Dorsey (

2020) describe as the “fencing in of democracy,” whereby enforcement strategies discipline movement, racialize belonging, and perpetuate power asymmetries.

Ultimately, the contradiction at the heart of the Lukeville PoE closure lies in the discrepancy between its stated justification and its actual outcomes. Far from enhancing national security or a humane border, the closure exacerbated humanitarian crises, destabilized local communities, and violated international law, including protections against collective punishment and inhumane treatment under Article 3 of the Convention Against Torture. The transportation of migrants in prison buses, without adequate medical care that Authors 1 and 2 repeatedly witnessed, further criminalized lawful asylum claims (

Sanchez et al. 2024). The Lukeville PoE closure thus exemplifies how border governance functions not as a neutral response to migration flows but as a deliberate articulation of neglect and disruption (

Kocher 2021;

Elías 2024;

De la Torre et al. 2025). Together, these frameworks reconfigure enforcement as both a symbolic and material project of ongoing exclusion, obscuring the state’s responsibility to vulnerable borderlands communities while increasingly investing in broader militarization.

6. Limitations and Future Studies

Our analysis, though based on robust ethnographic research, faced several limitations tied to broader challenges in borderlands ethnography and policy. The most significant was our inability to conduct formal interviews with U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officers, Border Patrol agents, or federal officials. In southern Arizona’s politicized climate, concerns about legal or professional repercussions led many federal employees to decline to participate or to be advised against it. This restricted our ability to access the internal logic behind the Lukeville PoE closure or to inquire why there was such inconsistent communication between CBP agents and humanitarian aid groups, such as Humane Borders. This reflects

Muñiz’s (

2022) and

Heyman’s (

2021b) findings on how disciplinary cultures within immigration enforcement inhibit transparency.

Ethical concerns also limited interviews with migrants actively navigating the asylum process. Engaging with individuals in distress or in a state of legal limbo risked traumatization and potential legal harm. As

Avalos (

2022) and

Bejarano and Sánchez (

2023) note, conducting ethical research in high-risk contexts requires careful attention to avoid extractive practices. We therefore relied on triangulated methods, which strengthened our analysis but left some gaps in first-person migrant perspectives. Future work should prioritize the voices of migrants from Lukeville and, where possible, accounts from current or former federal agents. Finally, the temporal proximity of data collection captured immediate disruptions but not long-term effects. Longitudinal studies are necessary to evaluate the lasting effects on the communities as well as the economic and policy impacts. The reemergence of exclusionary policies under the 2025 Trump administration underscores how increasingly hostile climates toward researchers and migrants may further constrain such work (

Kocher 2025).

7. Policy Recommendations

As researchers who have lived, worked, and researched in the Arizona borderlands for a significant period, we argue that the Lukeville PoE closure exemplifies how border enforcement, when shaped by political ideology rather than empirical need or humanitarian principles, generates harm not only for migrants but also for entire communities. Drawing on our findings, we propose the following policy recommendations to address these failures and reorient U.S. border policy toward justice, transparency, and care for asylum seekers and the communities that depend on the border in their daily lives.

Keep Ports of Entry Open: Ports of entry are vital humanitarian lifelines and essential to honoring asylum seekers’ rights to declare asylum. Abrupt closures weaponize disruption and neglect. Ports must remain open, with increased staffing and resources to process asylum claims.

Reform Asylum Seeker Access: Expand walk-up processing, decrease the penalization of asylum seekers presenting themselves between ports of entry, ensure access to translation services, and guarantee that migrants without phones or digital literacy are not excluded from these services.

Legalize and support community humanitarian aid: Federal and state agencies should fund, not criminalize, humanitarian networks. Libraries, clinics, and grassroots organizations should be recognized as integral to emergency response and be provided with additional resources in times of emergency.

Center Indigenous Sovereignty and Decision-Making. Tribal governments must be included in the decision-making process, and past or ongoing failure to recognize Indigenous rights to land and inclusion must cease immediately. Policies should protect mobility, land, and commerce for Indigenous nations across the border.

Prepare for Future Closures: Communities and stakeholders at the state and federal levels must develop harm reduction strategies, including pre-positioned aid caches, transparent communication channels with embedded communities, and coordination with humanitarian actors to mitigate crisis conditions if closures recur, which we believe they will.

8. Conclusions

The 2023–2024 closure of the Lukeville port of entry starkly illustrates, in an exploratory, real-time approach, how federal border governance actively produces harm through historical neglect and disruption, resulting from the deliberate exercise of control. Rather than enhancing security, the PoE closure destabilized entire communities: asylum seekers were denied protection, local aid networks were overwhelmed, families were separated, small businesses suffered, and Indigenous sovereignty was undermined. These outcomes were neither accidental nor unforeseeable; they are predictable consequences of PTD-based governance. By shutting a port of entry with little warning and no mitigation plan, the U.S. government violated its obligations under domestic asylum law and international human rights frameworks, weaponizing scarcity and instability against already vulnerable populations. The human and social toll of this closure underscores the ways border policies reproduce historical inequities. Far from increasing safety, the Lukeville closure intensified humanitarian crises and transferred responsibility for migrant welfare onto under-resourced communities. Future border governance must reject disruption as a strategy. Policy should prioritize harm reduction, preparedness, and respect for human rights and Indigenous sovereignty.

The resilience demonstrated by Lukeville communities is remarkable, but resilience cannot substitute for honoring human rights and offering State protection. Sustainable, humane immigration policies demand investment, education, and systemic redesign that center the lived realities of asylum seekers and border residents, protect life and mobility, and affirm that the suffering caused by closures like Lukeville is neither natural nor inevitable, but the result of choices that can and must be changed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.R. and G.S.-B.; Methodology, B.R. and G.S.-B.; Validation: B.R., G.S.-B. and J.O.; Formal Analysis, B.R., G.S.-B. and J.O.; Investigation, B.R. and G.S.-B.; Resources, B.R.; Data Curation, B.R. and G.S.-B.; Writing—original draft preparation, B.R., G.S.-B. and J.O.; Writing—review and editing, B.R., G.S.-B. and J.O.; Visualization, B.R.; Supervision, B.R.; Project Administration, B.R.; Funding Acquisition, B.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Given these factors and the non-interventional, anonymous nature of the study, no formal IRB approval was sought, and the study falls within the scope of ethically exempt research under U.S. federal guidelines.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- American Immigration Council. 2025. Asylum in the United States. May 19. Available online: https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/fact-sheet/asylum-united-states/ (accessed on 22 March 2025).

- Andreas, Peter. 2012. Border Games: Policing the US-Mexico Divide. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Anzaldúa, Gloria. 1986. Borderlands/La frontera: La Nueva Mestiza. Madrid: Capitán Swing Libros. [Google Scholar]

- Avalos, Miguel A. 2022. Border regimes and temporal sequestration: An autoethnography of waiting. The Sociological Review 70: 124–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejarano, Cynthia, and María Eugenia Hernández Sánchez. 2023. Geographies of friendship and embodiments of radical violence, collective rage, and radical love at the US–Mexico border’s Paso del Norte region. Gender, Place & Culture 30: 1b012-1034. [Google Scholar]

- Boyce, Geoffrey Alan. 2019. The Neoliberal Underpinnings of Prevention Through Deterrence and the United States Government’s Case Against Geographer Scott Warren. Journal of Latin American Geography 18: 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush-Joseph, Kathleen. 2024. Outmatched: The US Asylum System Faces Record Demands. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. Available online: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/outmatched-us-asylum-system (accessed on 7 April 2024).

- Castañeda Perez, José Ignacio. 2023. When Is Lukeville Border Crossing Reopening? Here’s What We Know. Arizona Republic, December 19. Available online: https://www.azcentral.com/story/news/politics/border-issues/2023/12/19/is-lukeville-arizona-border-crossing-open-today-heres-why-not/71960014007/ (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Cebulko, Kara. 2025. The Borders of Privilege: 1.5-Generation Brazilian Migrants Navigating Power Without Papers. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chacón, Jennifer M. 2021. The criminalization of immigration. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, Robert Keith. 2023. Intersectionality and ethnography. In Research Handbook on Intersectionality. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 204–22. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, Daniela Wenzel da. 2022. The United States’ Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) Agency and the Dehumanization of Latin American Immigrants. Santa Cruz do Sul: Universidade de Santa Cruz do Sul. [Google Scholar]

- Cothran, Cheryl, Thomas Combrink, and Melinda Bradford. 2012. Ajo Visitor Study. Available online: https://tourism.az.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/3.4_CommunityStudiesAndAssessments_Ajo-Visitor-Study-2012-Final-Report.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2020).

- Cunningham, Hilary. 2020. 8 Necrotone: Death-Dealing Volumetrics at the US-Mexico Border. In Voluminous States: Sovereignty, Materiality, and the Territorial Imagination. Edited by Franck Billé. New York: Duke University Press, pp. 131–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, Rob. 2023. Migrant Dies after He Is Located in Medical Distress near Lukeville, Arizona. U.S. Customs and Border Protection. September 5. Available online: https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/national-media-release/migrant-dies-after-he-located-medical-distress-near-lukeville (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- David, Gabrielle, ed. 2023. Lukeville POE Closed Monday to the Dismay of Many. Ajo Copper News, December 6. Available online: https://www.cunews.info/a4c1n/CuNews231206.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- De la Torre, Jesus M., Brenda Peralta, and Karla Rivas. 2025. “Do Not Come”: The US Root Causes Strategy and the Co-optation of the Right to Stay. Journal on Migration and Human Security 13: 112–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De León, Jason. 2015. The Land of Open Graves: Living and Dying on the Migrant Trail. Berkeley: University of California Press, Vol. 36. [Google Scholar]

- Del Bosque, Melissa. 2023. Ajo Residents, Activists Protest Inhumane Conditions for Asylum Seekers. Theborderchronicle.com. The Border Chronicle, August 15. Available online: https://www.theborderchronicle.com/p/ajo-residents-activists-protest-inhumane (accessed on 21 September 2025).

- Díaz-Barriga, Miguel, and Margaret E. Dorsey. 2020. Fencing in Democracy: Border Walls, Necrocitizenship, and the Security State. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Elías, María Verónica. 2024. Managing Security and Immigration at the US–Mexico Border: A Foucauldian Perspective. Journal of Borderlands Studies 39: 411–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Gonzalez, Nilda, Emir Estrada, Michelle Tellez, Daniela Carreon, and Brittany Romanello. 2024. The Impact of the 100-mile Border Enforcement Zone on Mexican Americans in Arizona. American Behavioral Scientist, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frati, David. 2017. Snowbirds’ Gift Economy in the Arizona Desert. Métropolitiques. HAL Id: halshs-02880337. Available online: https://shs.hal.science/halshs-02880337v1 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Golash-Boza, Tanya, and Cecilia Menjívar. 2012. Causes and consequences of international migration: Sociological evidence for the right to mobility. The International Journal of Human Rights 16: 1213–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haro, Lupita. 2023. Ola de Violencia en Sonora: Se Enfrentan Militares y Hombres Armados en Sonoyta, December 30. Available online: https://www.debate.com.mx/policiacas/Ola-de-violencia-en-Sonora-Se-enfrentan-militares-y-hombres-armados-en-Sonoyta-20231230-0155.html (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Harrison, Faye V. 2025. Racialization, Criminalization, and the Articulation of Multiple Alterities: A Perspective on the United States. In Visibilities and Invisibilities of Race and Racism. London: Routledge, pp. 186–213. [Google Scholar]

- Heyman, Josiah. 2021a. The US-Mexico border since 2014: Overt migration contention and normalized violence. In Handbook on Human Security, Borders and Migration. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 54–70. [Google Scholar]

- Heyman, Josiah. 2021b. Summary: Virtual Walls. In The Proliferation of Border and Security Walls Task Force. Washington, DC: American Anthropological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Caitlin Stephen, David Culver, and Evelio Contreras. 2024. How the US-Mexico Border Brought Trouble to the Tohono O’odham Nation. CNN, June 24. Available online: https://www.cnn.com/2024/06/24/americas/migration-us-mexico-border-tohono-oodham-intl-latam (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- International Rescue Committee. 2024. Note by the High Commissioner. Note on International Protection. International Journal of Refugee Law 36: 152–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISDA. 2024. Sonoran Desert Biosphere Region Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy; Isdanet.org/Isda-Newsfeed. Ajo: International Sonoran Desert Alliance. Available online: https://www.isdanet.org/s/SDBR-CEDS-FINAL-10-22-2024-size-reduced.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Johanson, Emily J. 2020. The Migrant Protection Protocols: A Death Knell for Asylum. UC Irvine Law Review 11: 873. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, Miriam. 2024. African Migration to the US Soars as Europe Cracks Down. International New York Times, January 5. [Google Scholar]

- Kocher, Austin. 2021. Migrant protection protocols and the death of asylum. Journal of Latin American Geography 20: 249–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocher, Austin. 2025. The Migrant Disappearance Protocols: Trump Sends Immigrants to ‘Legal Black Hole’ at Guantánamo Bay. Substack.com. Austin Kocher, February 13. Available online: https://austinkocher.substack.com/p/the-migrant-disappearance-protocols (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Kravitz, Caroline. 2024. Immigration Enforcement and Health—Urban Health Collaborative. Urban Health Collaborative. Available online: https://drexel.edu/uhc/resources/briefs/Immigration-Enforcement-and-Health/ (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Madsen, Kenneth D. 2024. Indigenous sovereignty and Tohono O’odham efforts to impact US-Mexico border security. Latin American and Caribbean Ethnic Studies 19: 44–68. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, Emmy. 2024. Trump on Immigrants: ‘We Got a Lot of Bad Genes in Our Country Right Now’. POLITICO, October 7. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, Daniel, and Jeremy Slack. 2013. What part of ‘illegal’ don’t you understand? The social consequences of criminalizing unauthorized Mexican migrants in the United States. Social & Legal Studies 22: 535–51. Available online: https://www.politico.com/news/2024/10/07/trump-immigrants-crime-00182702 (accessed on 7 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Mellon Humanities Postdoctoral Fellowship Program. 2023. U.S. National Park Service. National Parks Service. July 24. Available online: https://www.nps.gov/orgs/1296/index.htm (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Menjívar, Cecilia, and Leisy Abrego. 2012. Legal Violence: Immigration Law and the Lives of Central American Immigrants. American Journal of Sociology 117: 1380–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miroff, Nick. 2023. US faces’ unprecedented ‘border surge as immigration deal stalls in DC. The Washington Post, December 20. [Google Scholar]

- Muñiz, Ana. 2022. Borderland Circuitry: Immigration Surveillance in the United States and Beyond. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, Alexandra K., Colin Jerolmack, and DeAnna Smith. 2021. Ethnography, data transparency, and the information age. Annual Review of Sociology 47: 41–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neustadt, Robert. 2017. Intervention II: Borders: Strangers and neighbors: The Tohono O’odham and the myth of’ us versus them” on the US/Mexico Border. CrossCurrents 67: 577–89. [Google Scholar]

- Nevins, Joseph. 2002. Operation Gatekeeper: The Rise of the “Illegal Alien” and the Remaking of the US–Mexico Boundary. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Orsi, Jared. 2023. People of a Sonoran Desert Oasis. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. [Google Scholar]

- Painter, Fantasia Lynn. 2021. Bordering the Nation: Land, Life, and Law at the US-Mexico Border and on O’odham Jeved (Land). Berkeley: University of California. [Google Scholar]

- Piekielek, J. 2016. Creating a Park, Building a Border: The Establishment of Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument and the Solidification of the US-Mexico Border. Journal of the Southwest 58: 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Reineke, Robin. 2019. Necroviolence and Postmortem Care Along the US-México Border. Lowell: Amerind Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes, Victoria. 2020. Ethnographic toolkit: Strategic positionality and researchers’ visible and invisible tools in field research. Ethnography 21: 220–40. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, GE, Samuel Loroña, and Zachary Goodwin. 2024. Reimagining the Migration Protection System: Critical Reflections from the USMX Border. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/120590539/Reimagining_the_Migration_Protection_System_Critical_Reflections_from_the_USMX_Border (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Santos, Wanessa Alves. 2024. Entre fronteiras: Crianças migrantes desacompanhadas detidas na travessia México-EUA. C@LEA-Cadernos de Aulas do LEA 13: 104–15. [Google Scholar]

- Silver, Alexis M., and Melissa A. Manzanares. 2023. Transnational ambivalence: Incorporation after forced and compelled return to Mexico. Ethnic and Racial Studies 46: 2612–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, Gabriella. 2021. Absent and present: Biopolitics and the materiality of body counts on the US–Mexico border. Journal of Material Culture 26: 43–63. [Google Scholar]

- Stephen, Lynn. 2007. Transborder Lives: Indigenous Oaxacans in Mexico, California, and Oregon. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, Haeden Eli, Ian Ostericher, Cameron Gokee, and Jason De León. 2016. Surveilling surveillance: Countermapping undocumented migration in the USA-Mexico borderlands. Journal of Contemporary Archaeology 3: 159–74. [Google Scholar]

- Tasker, Keegan C. 2019. Waived; The Detrimental Implications of US Immigration and Border Security Measures on Southern Border Tribes-An Analysis of the Impact of President Trump’s Border Wall on the Tohono O’Odham Nation. American Indian LJ 8: 303. [Google Scholar]

- Trump, Donald. 2018. Remarks by President Trump on the Illegal Immigration Crisis and Border Security; Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Administration, November 1. Available online: https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-president-trump-illegal-immigration-crisis-border-security/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- U.S. Customs and Border Patrol. 2023. Statement from CBP on Operations in Lukeville, AZ. U.S. Customs and Border Protection. December 2. Available online: https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/national-media-release/statement-cbp-operations-lukeville-az (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Wilson, Michael Steven, and Jose Antonio Lucero. 2024. What Side Are You On?: A Tohono O’odham Life Across Borders. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, Tom K. 2023. Lives in Danger: Seeking Asylum Against the Backdrop of Increased Border Enforcement. San Diego: US Immigration Policy Center. [Google Scholar]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).