1. Introduction

In recent decades, the role of universities has increasingly expanded beyond teaching and research, giving rise to the so-called Third Mission (

Compagnucci and Spigarelli 2020). Within this framework, university-based incubators have historically played a key role in fostering innovation and technology transfer (

Galbraith et al. 2019). However, alongside these traditional models, a specific form of incubation has emerged: social incubation (

Ackerley 2019). Among these, university social incubators stand out as mechanisms supporting cooperatives and social enterprises, and Social and Solidarity Economy (SSE) initiatives, seeking not only economic sustainability but also addressing social and environmental challenges (

Nicolopoulou et al. 2017;

Marconatto et al. 2019).

Since the mid-20th century, the relationship between universities, the science and technology system, and their socioeconomic environments has gained growing importance in academic debates and institutional strategies. Various perspectives and approaches to socio-technical links have emerged, in both central and peripheral countries (

Trencher et al. 2014;

Alonso et al. 2021). This focus has revalued one of the three substantive functions of the university, traditionally less recognized in the academic field: university–science and technology linkages, known in various contexts as the “Third Mission”, “university extension”, “linkage” or “technology transfer” (

Arzadun and Picado-Arroyo 2024a,

2024b).

In Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), this evolution gained particular significance at the beginning of the 21st century when the II Regional Conference on Higher Education (CRES) held in 2008 in Cartagena, Colombia, proclaimed higher education as a human right and a social public good that must be guaranteed by the State. This principle, reaffirmed at the III CRES in 2018 in Argentina, has been fundamental in promoting the democratization of universities and knowledge, while strengthening links between university, scientific–technical systems and societal needs.

The socio-technical link between universities and society in the region manifests mainly in two areas: innovation and technological transfer on one hand, and university extension or social linkage on the other (

Pastore 2019). However, these areas tend to develop in parallel with little interaction and sometimes contradictory approaches. University extension, part of the regional agenda since the early 20th century university reform, experienced critical renewal in recent decades, influenced by organized social demands, university community responses, and institutional and policy contexts (

Pastore 2015). Simultaneously, technological innovation and linkage gained prominence in university strategies seeking to contribute to economic development, often associated with generating complementary income through services, innovation, or patents (

Casas and Luna 1997;

Di Meglio 2017).

Although the literature on technological and business incubators is extensive, research focusing on university social incubators and their contribution to strengthening the SSE remains limited (

Sansone et al. 2020). In this sense, university social incubators deserve greater attention, especially in comparative perspective. This gap is particularly evident when examining the role of universities in supporting SSE initiatives through dedicated incubation programs, particularly in contexts where such practices have emerged as strategic responses to socioeconomic exclusion and the need for alternative development pathways.

This article presents partial results of a broader international research project.

1 While the project as a whole investigates the relationship between universities, knowledge democratization, and the SSE, the present article focuses specifically on the survey data collected in Argentina and Brazil. These two countries are of particular interest, as they display a greater diffusion of university social incubators compared to many European contexts, with Brazil showing a stronger institutionalization of such initiatives through public programs such as PRONINC and ITCP.

The objective of this article is therefore to analyze the extent to which university social incubators in Argentina and Brazil support and strengthen projects within the SSE. By focusing on this dimension, the article seeks to contribute to the international debate on university incubators, moving beyond technological and market-oriented perspectives and highlighting the role of universities as active agents in fostering inclusive and sustainable development.

University incubation trajectories promoted in Argentina and Brazil are typically based on perspectives and interaction strategies consistent with alternative economy principles such as reciprocity, solidarity, mutual aid, community, equality and economic democratization (

Coscarello 2024b;

Pastore 2024); These approaches favor bi-directional exchange and knowledge dialogue between university communities and social actors, challenging conventional unidirectional technology transfer or profit-oriented business incubation models. In this context, the study seeks to comparatively examine university social incubation models in both countries, with a focus on initiatives linked to the Social and Solidarity Economy (SSE), in order to understand their contributions to knowledge democratization, inclusive territorial development, and the strengthening of university-society linkages.

The following sections present the methodology and comparative analysis of university social incubation trajectories and characteristics in both countries, contributing to understanding how these initiatives promote democratized knowledge and inclusive development pathways within the framework of higher education as a human right and public social good.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. University Social Incubation: From Business Models to Social Innovation

University-based business incubation has historically played a central role in fostering innovation and technology transfer (

Galbraith et al. 2019). In recent decades, however, social incubation has emerged, one of its main variants being the incubation of cooperatives, social enterprises, and Social and Solidarity Economy (SSE) initiatives (SSE). This form of incubation aims not only at economic sustainability but also at addressing social and environmental challenges (

Pandey et al. 2017;

Nicolopoulou et al. 2017;

Marconatto et al. 2019).

The literature distinguishes between business, hybrid, and social models, depending on the degree of social impact of the initiatives incubated (

Sansone et al. 2020) or alternatively, between technological, business, and social incubators (

Coscarello et al. 2023). In Latin America, particularly in Brazil and Argentina, university social incubators have assumed a growing role, often linked to practices of university extension and socio-technical engagement (

Addor and Lariccia 2018;

Cruz 2014;

Hernández Arteaga and Pérez Muñoz 2020;

Pastore 2019,

2024).

Recent studies highlight that university incubators can strengthen the capacities of social entrepreneurs by fostering empowerment processes and acting as “conversion factors” that transform ideas into sustainable initiatives (

Farransahat et al. 2021). The performance of incubators, however, should not be measured solely in terms of start-up growth. Their social and territorial impact must also be considered. Comparative analyses show that university incubation centers differ in their success metrics: some emphasize the number of firms launched, others the creation of qualified employment, and still others the capacity to generate inclusive social innovation (

Kulkarni et al. 2024).

A crucial aspect concerns the role of incubators as linkages between universities and local communities. In several contexts, they have fostered regional development by promoting collaboration between universities, public institutions, and social enterprises, thereby helping to reduce institutional and financial barriers (

Leal et al. 2023). This confirms that social incubation is not merely a technical–managerial process, but also a political and cultural device that strengthens the university–society connection.

Nevertheless, the uncritical application of conventional business incubation models to the SSE risks reproducing an instrumental economic rationality and conceptions of techno-scientific “neutrality” or “determinism.” Moreover, the university–society link often tends to align with for-profit enterprises, privileging the transfer of knowledge useful to them and thus contributing to implicit processes of knowledge and university privatization (

Dagnino 2016).

Compagnucci and Spigarelli (

2020) note that the Third Mission (TM) of universities offers significant potential but also faces notable constraints. Among these are the difficulties of integrating co-creation and social innovation with dominant models of technology transfer. Similarly,

Naranjo-Africano et al. (

2023) point out that barriers to the TM are both organizational and individual, and that overcoming them requires support structures and strong academic motivation.

Recent contributions reinforce the need to consider universities as key actors in implementing SSE experiences (

Amaral Pereira and Silva 2024;

Coscarello 2024b).

Van Mensel et al. (

2025) propose the concept of a Social Third Mission, which broadens the scope of the TM by emphasizing the social and environmental impact of universities. They show how, alongside teaching and research, universities can support local ecosystems of social innovation, promote responsible entrepreneurship, and contribute to the SDGs through education, co-creation, and non-commercial knowledge transfer. This perspective reframes the university as a “resource orchestrator” and as a builder of collaborative territorial ecosystems.

Similarly, the work of

Landaburú-Mendoza et al. (

2024), based on the analysis of rural associations in Ecuador, demonstrates that collaboration between universities and communities strengthens organizational and managerial capacities. It fosters participation, self-management, and collective learning through methodologies such as Participatory Action Research. Their findings highlight the catalytic role of universities in valuing local knowledge and building inclusive pathways to sustainable development.

These contributions show that the synergy between the TM and the SSE can enhance the transformative role of universities, reinforcing the democratization of knowledge and creating trajectories of economic and social development grounded in solidarity, reciprocity, and sustainability (

Pastore et al. 2022). Yet, to consolidate such experiences, it is essential to strengthen supportive policies, formally recognize the social dimension of the TM, and establish institutional frameworks that prevent university–SSE collaborations from remaining marginal or fragmented.

OECD (

2024) data confirm the growing global significance of the SSE, underscoring its dual economic and social contribution. The SSE encompasses cooperatives, associations, mutual societies, foundations, and social enterprises, which in many countries represent a substantial share of employment and value added. For instance, in Belgium and France the SSE employs over 10% of the national workforce, with a particularly high participation of women, especially in the sectors of social services, health, and education. The OECD also emphasizes that the SSE contributes to economic resilience even in times of crisis (such as during COVID-19), strengthens social cohesion, and plays a pivotal role in the green and digital transitions.

Challenges remain, including fragmented regulatory frameworks and the lack of systematic and comparable data, which hinder accurate measurement of its overall impact. For this reason, the OECD highlights the importance of developing shared monitoring systems and harmonized international definitions. Integrating these perspectives with university social incubation practices not only supports the SSE but also redefines the role of universities as central actors in building more inclusive, sustainable, and democratic societies.

2.2. Historical Development and Policy Context in Brazil and Argentina

2.2.1. Brazil’s Pioneering Experience

Brazil’s incubator development began with the founding of ANPROTEC in 1987, which now brings together over 300 entities including business incubators, technology parks, accelerators, and research institutions. The country experienced rapid growth from 10 incubators in 1991 to 135 by 2000 and approximately 400 by 2009, ranking third globally in incubator numbers (

ANPROTEC 2010;

Andrade 2012).

Brazil’s university incubators in the solidarity economy represent a remarkable contribution to socio-technical linkage in SSE. This innovative practice began three decades ago with the creation of the first Technological Incubator of Popular Cooperatives (ITCP) in 1995 at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, responding to massive poverty, job insecurity, and social exclusion. The University Network of Technological Incubators of Popular Cooperatives (Red ITCP) was formed in 1998, and around the same time, the National Program of Technological Incubators of Popular Cooperatives (PRONINC) was also developed (

Addor and Santos 2022).

The establishment of the Secretariat for Solidarity Economy within the Ministry of Labor in 2003 under Lula Da Silva’s first government reactivated PRONINC, leading to 65 financed incubators by 2009. By 2013, 84 university incubators in solidarity economy were financed through the program (

Addor and Lariccia 2018). These experiences converged in two university networks: the ITCP Network and the Unitrabalho Network, together grouping around a hundred university incubators. However, since 2016, there has been substantial decline in federal programs supporting solidarity economy, particularly affecting PRONINC. In fact, only the ITCP Network is currently operating.

ITCPs, as university incubators, can have diverse approaches and organizational structures, but since their origins they share the fact of being university extension programs, which in many cases combine research or training tasks on the subject, with the aim of incubating, associative socioeconomic organizations (whether formalized in cooperatives or not) of workers from popular sectors or in vulnerable situations. This orientation of including populations in conditions of exclusion or job insecurity through the incubation of associative or collective socioeconomic ventures is one of the main elements that differentiates ITCPs from traditional business incubators, which generally focus on incubating dynamic or innovative ventures (

Virolle et al. 2016). In this regard, ITCPs configure spaces of university extension committed to the popular sectors from a counter-hegemonic perspective, which aim to build and strengthen the solidarity economy from an approach that integrates popular education, social technologies and the social emancipation of popular groups organized in areas such as urban waste collection (“catadores”), precarious or self-employed workers, companies recovered by their workers, family and peasant agriculture, or popular and community finance (

Costa et al. 2023).

Through these initiatives, ITCPs reaffirm the transformative and critical tradition of Latin American university extension, based on the democratization of higher education and its recognition as a right. They expand access, relevance, and social utility of knowledge through horizontal, participatory, and dialogical co-creation with diverse social actors, particularly those historically excluded from universities (

Rojas 2017).

2.2.2. Argentina’s Fragmented Development

Argentina’s business incubator development began in the mid-1990s with two main types: those promoting general business development and others strengthening scientific-technological system connections. By 2003, there were around 14 business incubators, less than half of university origin. A second push occurred from 2004, coinciding with economic recovery after the 2001 crisis and strengthened public policies at national, provincial and municipal levels.

By 2014, nearly 50 entities were supporting entrepreneurs and SMEs across the country (

Aggio et al. 2014). However, according to

Jacobsohn (

2017), the number of incubators had increased significantly, reaching 371 registered in the National Registry (INCUBAR) by 2017, although only a small proportion became consolidated and maintained long-term operations. University incubator development included joint initiatives with government agencies, exemplified by the 1986 creation of the Scientific-Technological Network in Buenos Aires province (

Versino 2000).

For their part, university extension and public engagement gained strength in the early 21st century, particularly after the 2001 crisis, driven by the social demand of collective actors, the commitment of university communities, and policies promoting universities’ engagement with regional communities (

Estébanez et al. 2022). Within this framework, collaboration between public universities and organized actors in the popular economy and the SSE also strengthened, particularly since the International Year of Cooperatives in 2012. In this regard, academic research, innovation, and extension projects and initiatives multiplied, while specific academic networks were formed (

González et al. 2021), such as the University Network on Social and Solidarity Economy, RUESS in Spanish (

https://www.ruess.com.ar (accessed on 25 September 2025)) and the Technical Exchange Network with the Popular Economy, RITEP in Spanish (

https://intercambiotecnico.ritep.org (accessed on 27 September 2025)).

However, university incubation in SSE has not been as significant as in Brazil. Two factors may have influenced this. On the one hand, in Argentina, these university networks focused on the topic did not adopt social incubation as a primary strategy, as they did in the neighboring country. On the other hand, public policies for socio-technical engagement with SSE have shown less specificity in social incubation than in Brazil, as well as less long-term continuity, resulting in more fragmented development. For example, between 2014 and 2023, three relevant programs were launched in succession: (i) the Cooperativism and Social Economy Program in Universities (2014–2021); (ii) the Social Incubation and Strengthening Program (2018–2019); and (iii) the Incubator for Cooperatives and Mutual Care Societies (2021–2023).

2.3. Research Design and Data Collection

This exploratory study aims to contribute to the comparative understanding of university-based social incubation models in Argentina and Brazil, emphasizing their role in the sustainable territorial development and democratization of knowledge. Through a mixed methodological approach combining qualitative field-based observation and quantitative analysis, the research examines both institutional dynamics and socio-political contexts that shape these experiences.

This article adopts a mixed approach to the analysis of incubators in Argentina and Brazil. On the one hand, from a qualitative perspective, the research is based on the observation and direct participation of the authors in university social incubation projects in both countries, as well as on the review of bibliography and other relevant materials.

On the other hand, in the quantitative component, a study was carried out on the active incubators identified in Argentina and Brazil. To this end, a self-administered questionnaire was designed and implemented for incubators in both countries. First, a survey of information on incubators was carried out through the national agencies in charge of registering such experiences: the Ministry of Production and the Ministry of Social Inclusion in Argentina, and the Ministry of Science, Technology, Innovation and Communications in Brazil. Additionally, the information was triangulated with national associations and networks linked to incubation, such as the National Association of Promoters of Advanced Technology Companies (ANPROTEC) and the Network of Technology Incubators of Popular Cooperatives (ITCP) in Brazil, the latter representing university incubators in the field of the solidarity economy. In Argentina, the information was verified from the directory of incubators linked to the former Ministry of Productive Development, and from the University Network of Social and Solidarity Economy (RUESS).

Once the information was obtained, the databases were cleaned to identify the active incubators that met the necessary criteria to be considered as such. This made it possible to create a list of incubators that were active in each country during the fieldwork period, which is naturally less than the total available in the information databases. The reference period covered the years 2021–2022, so only those incubators that were active in that period and that met the specific requirements established for the selection were considered.

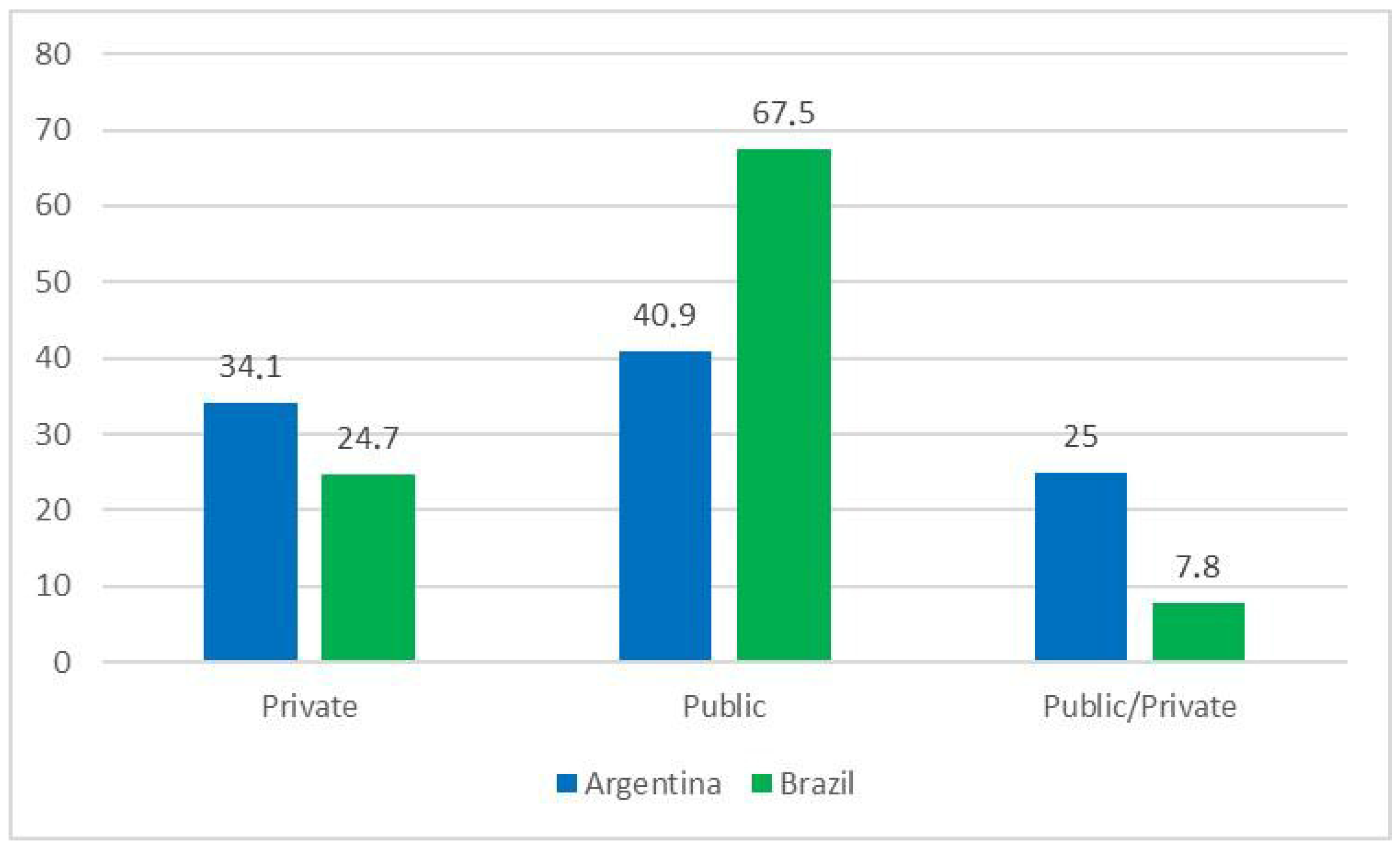

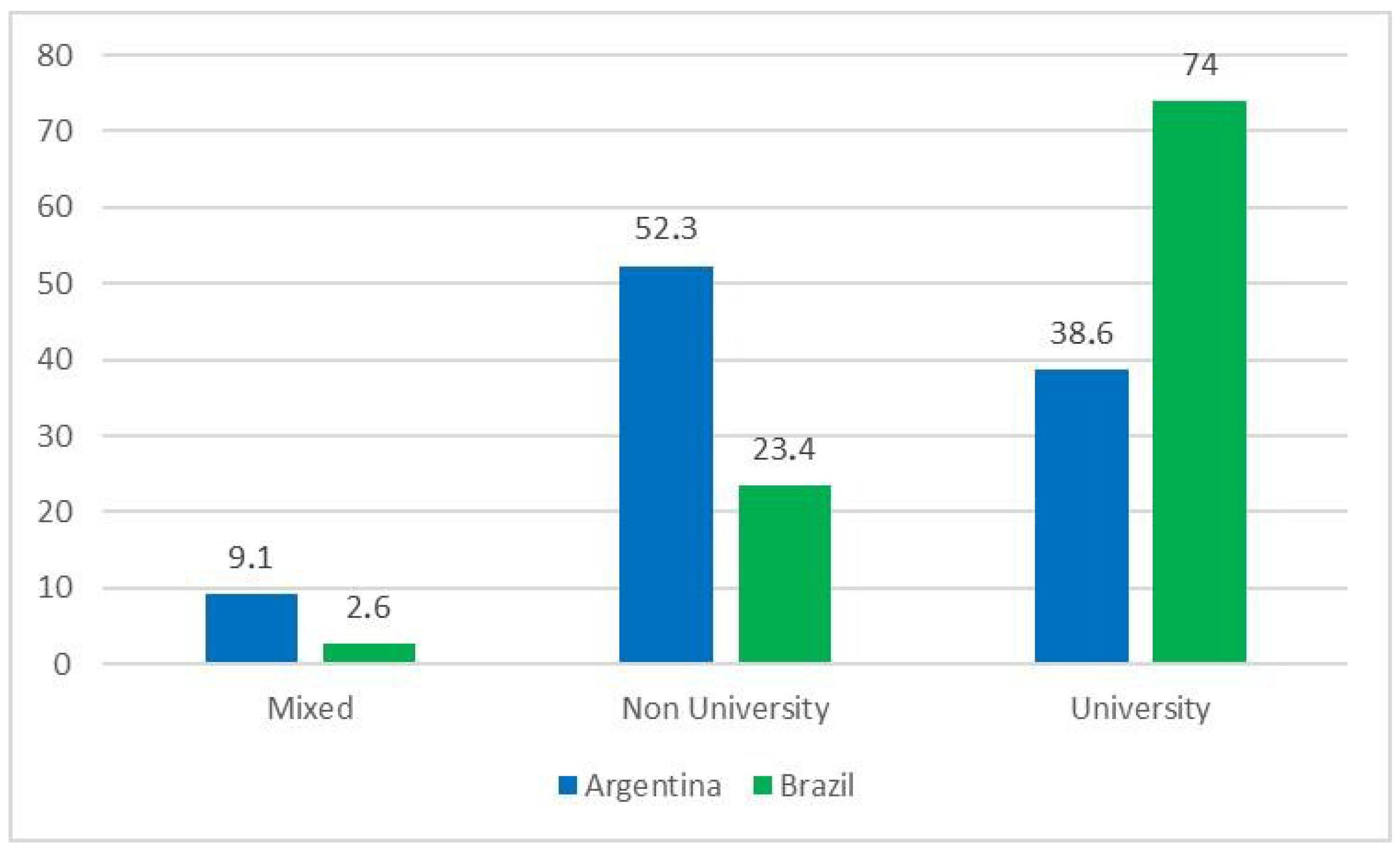

The quantitative fieldwork was carried out between November 2022 and March 2023. With this data, a directory composed of 277 incubators was built: 186 in Brazil and 91 in Argentina. The sample obtained in the survey included 77 incubators in Brazil and 44 in Argentina, representing 41.4% and 48.3% of the directory of incubators in each country, respectively.

Table 1 summarizes the main methodological aspects of the study. Specifically, the following sections present the results of the survey conducted in the two Latin American countries.

The questionnaire was sent to incubators and accelerators. Since accelerators share the same objective as incubators (

Mian et al. 2016) and the differences between the two are not always obvious (

Sansone et al. 2020), the term “incubator” will be used in this article to refer to both incubators and accelerators. It is relevant to note that, for this article, a “university incubator” is defined as one in which the university has a dominant participation in its control (

SIM 2025). In addition, a “mixed incubator” is considered when the management of the incubator is carried out by government agencies and/or universities.

For the purpose of presenting the results on incubators in Argentina and Brazil and their typologies, we adopt the following acronyms: ‘mixed-BS’ for mixed business–social incubators, ‘mixed-PP’ for mixed government–university incubators, and ‘mixed-UN’ for mixed university-oriented incubators.

The selection of incubators was carried out under three criteria: (i) that they offer ongoing support services for the creation or development of companies or ventures; (ii) that they define themselves as incubators or accelerators; and (iii) that they have been active during the years 2021–2022. For university incubators, the university was considered a single entity, although in some cases there could be multiple initiatives under its management.

In both countries, university incubators are distributed across all regions. In Argentina, university and mixed-BS incubators are mainly prevalent in the AMBA (Buenos Aires Metropolitan Area) and in the Pampas region. In Brazil, university incubators are prevalent in the Southeast and South.

Given the exploratory nature of this study and the limited size of the sample, the results should be interpreted as indicative trends rather than generalizable findings. This approach is consistent with the objective of capturing emerging patterns in the development of university social incubators in Argentina and Brazil.

All materials, survey tools, and anonymized datasets can be made available upon reasonable request. No generative AI was used in the design, collection, or analysis of the data. This study did not involve human participants or require ethical approval.

4. Discussion: Analysis of the Results of the Quantitative Study

The empirical findings presented in this study provide relevant insights into the trajectories of university social incubation in Argentina and Brazil, and allow for a comparative discussion both within the regional context of Latin America and with international experiences.

The survey results highlight clear differences between Argentina and Brazil, but they also confirm a broader tendency: university social incubators are more numerous and more active in SSE projects in Latin America than in many European contexts. This finding reinforces the relevance of analyzing social incubation as a distinctive model that goes beyond the technological and market-oriented approaches prevalent in Europe.

This study employs classification typologies that recognize social incubation as a distinct model (one of them in particular, being incubation in SSE), considering particularly its public or private origin and, in particular for this study, the type of relationship with university entities. In this sense, and in the same direction as other contributions on the subject, the work highlights social incubators as strategic tools to promote economic and social development at the territorial level, especially in the field of SSE.

From this general framework, the work draws some important corollaries for the analysis of university social incubation in both countries. On the one hand, in Brazil there are many more incubators than in Argentina, both in relative and absolute terms, among which the university incubators of “popular cooperatives” or SSE ventures have a significant degree of development. On the other hand, according to the responses received in the sample of the empirical study, it appears that in both countries, public or mixed-PP entities prevail over private entities in incubation initiatives, a situation very different from what other studies characterize for the European context (

SIM 2021). Likewise, incubators linked to the academic world predominate, or mixed-UN ones with university participation in management, also different from the European context where non-university incubators prevail.

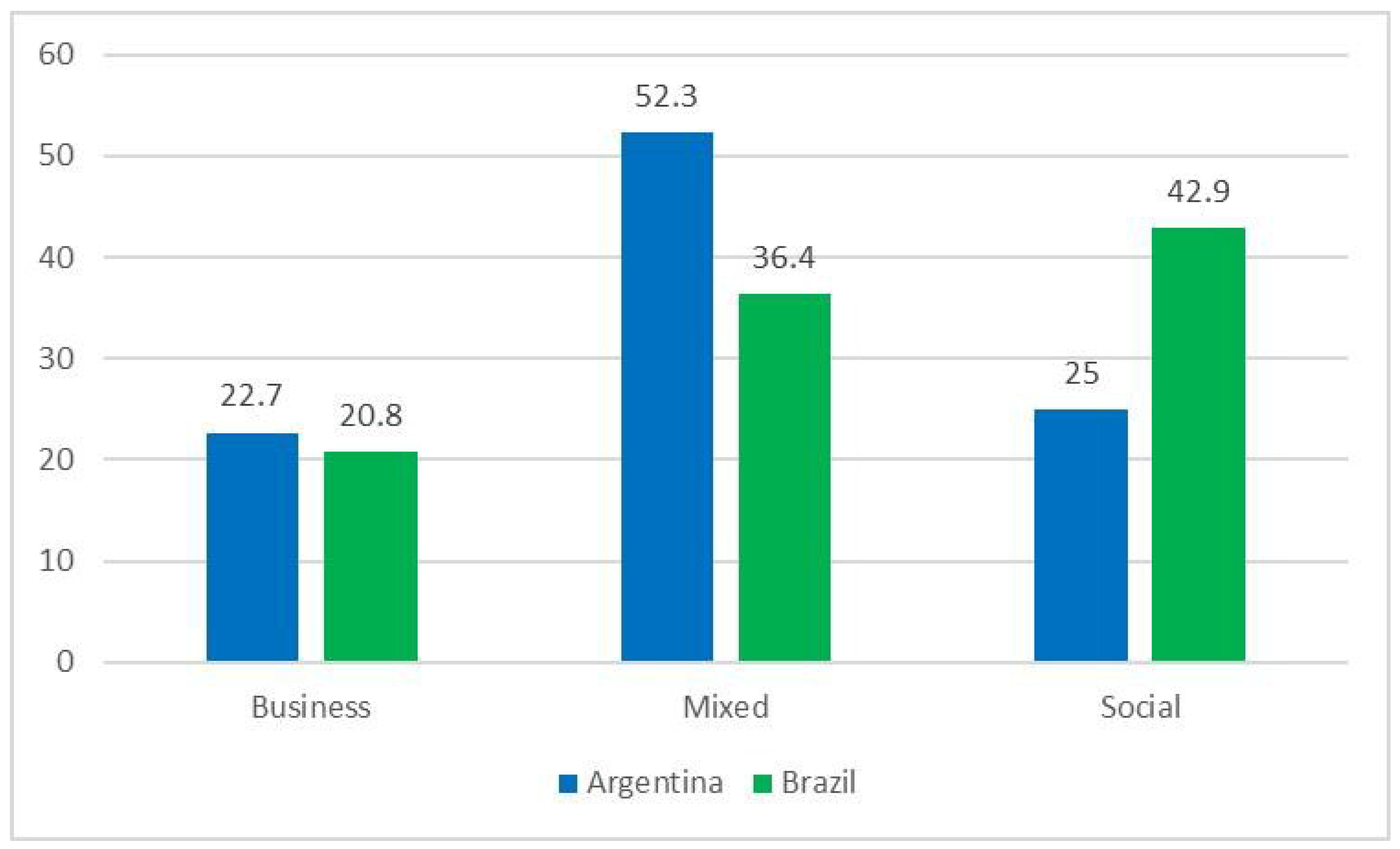

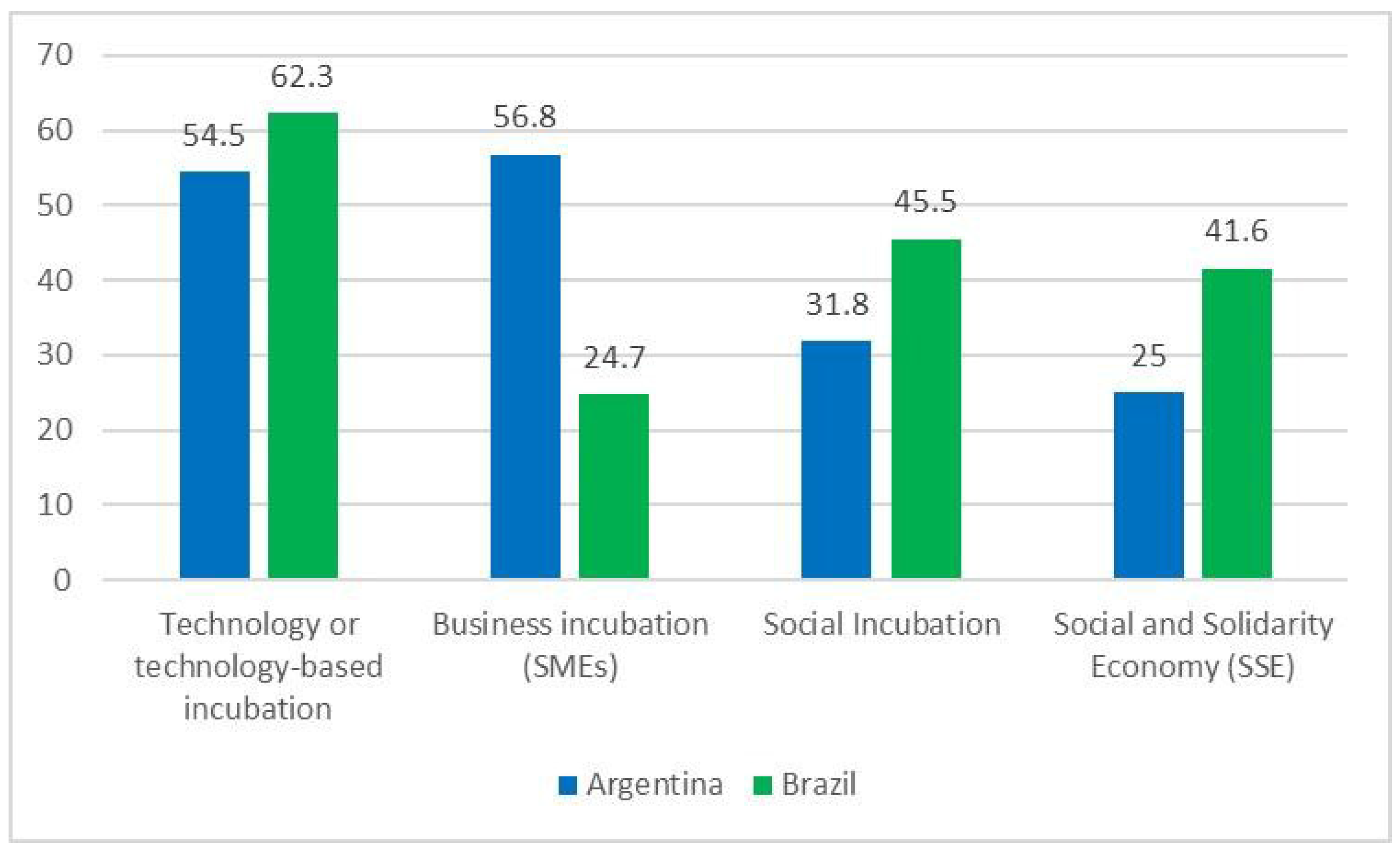

As regards the type of incubation, in Argentina and Brazil, those dedicated to social or mixed-BS incubation stand out, which according to information from both countries represent just over three out of every four incubators; only in the first case, mixed-BS incubators prevail, while in Brazil, social incubators prevail. This is also very different from the studies carried out for the European case, with a higher proportion of business incubators compared to these two South American countries.

Also, a unique contribution of the empirical study in these countries has been a specific query for those incubators that defined themselves as social, regarding whether or not they worked with SSE ventures. At this point, it is observed that in both cases, the majority of them responded affirmatively—nine out of ten social incubators work with the SSE in the case of Brazil and almost eight out of ten in the case of Argentina. In line with this, in both countries, these incubators that work with the SSE mostly have university ties.

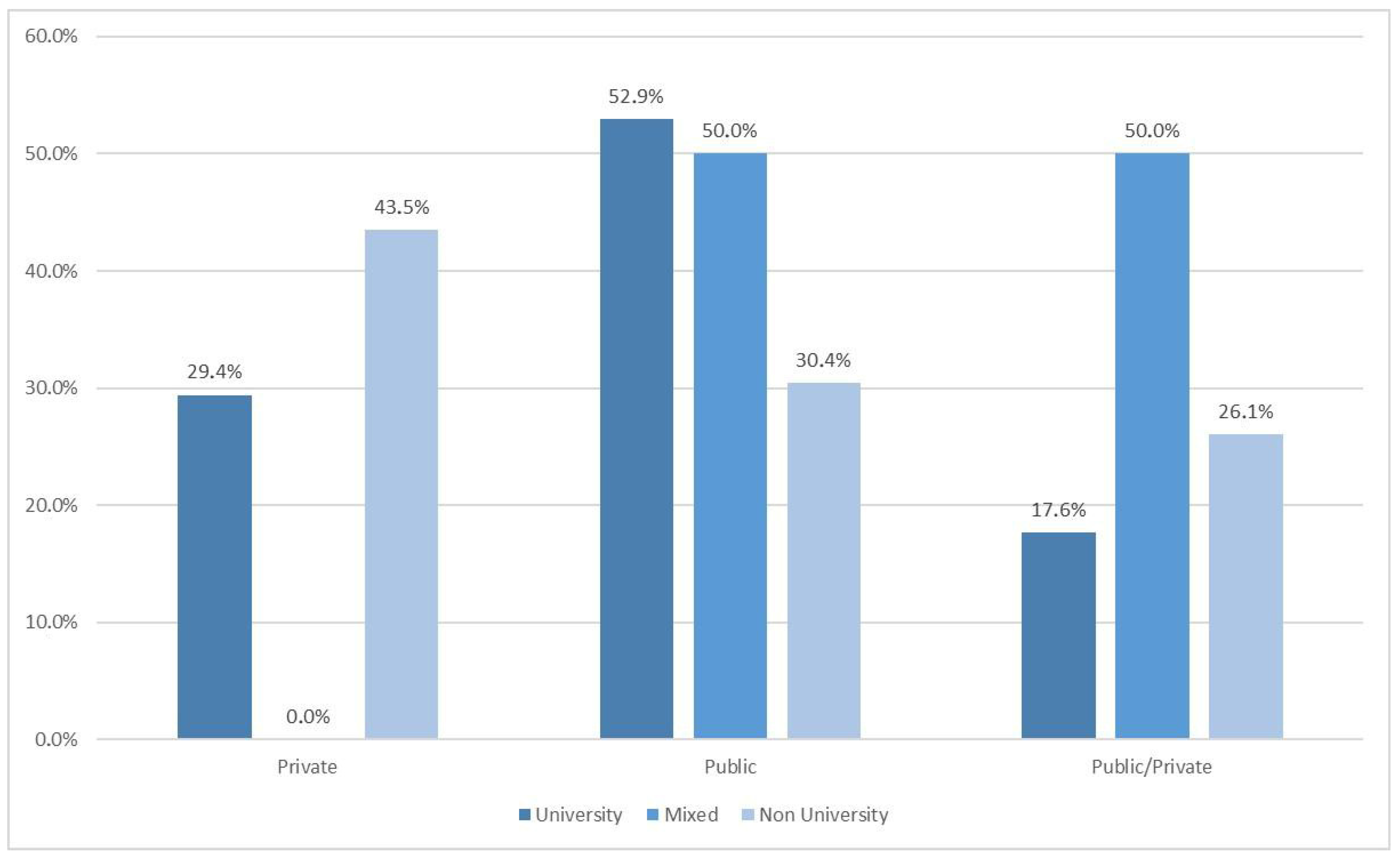

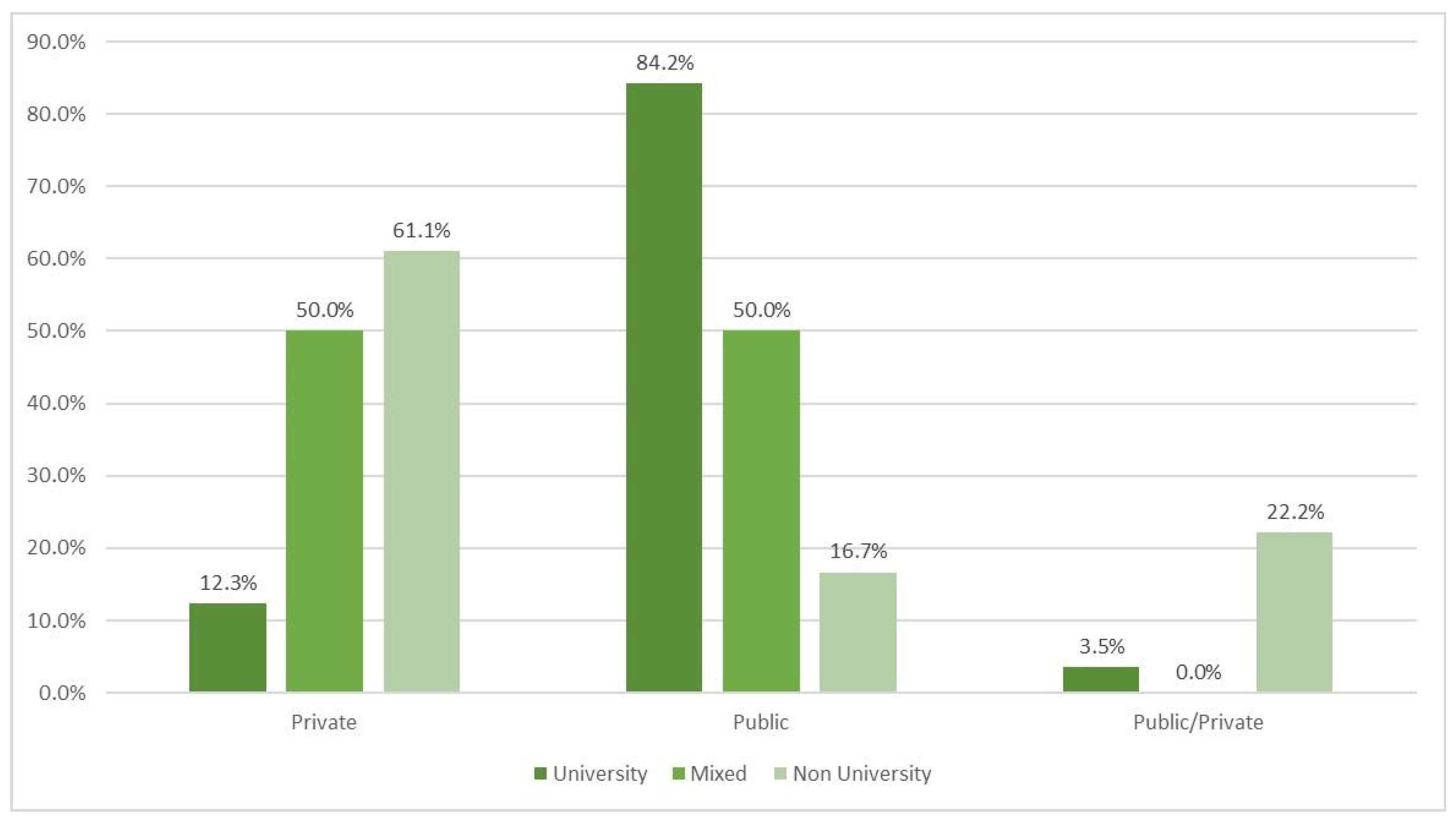

In the specific case of university or mixed-UN incubators, in Argentina half are public, while in Brazil it is similar in the case of mixed-UN incubators, but much higher in university incubators—in the sample 8 out of 10 university incubators are public.

Furthermore, a higher proportion of university linked SSE incubators is confirmed in Brazil compared to Argentina, illustrating the long-standing trajectory of policies such as PRONINC and the consolidation of the ITCPs network, which provided institutional stability and financing for SSE incubation. Argentina, by contrast, has followed a more fragmented path, with shorter-term programs and lower continuity. These structural differences may explain the lower prevalence of social incubators formally connected to academia.

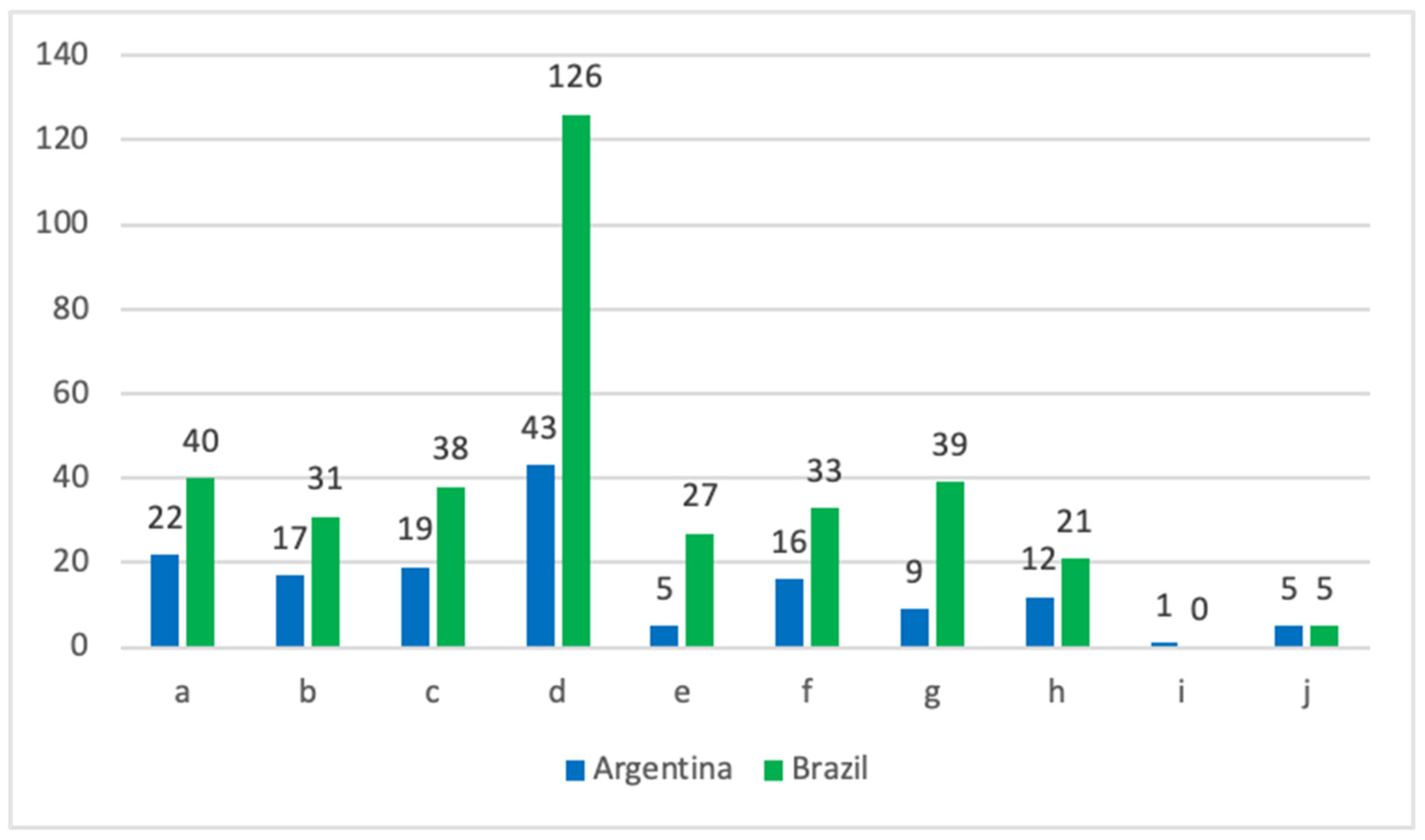

The services offered by these university incubators are predominantly training and technical assistance, as well as tutoring and support for economic management, group relations and networking. This confirms that, particularly in Brazil, incubators have purposes that go beyond business creation or competitiveness, playing a strategic role in addressing socioeconomic vulnerabilities. The finding that a large proportion of social incubators work specifically with SSE ventures and initiatives reinforces their role as knowledge democratizers and platforms for alternative development paths (

Cruz et al. 2024;

Dagnino 2016). These practices align with traditions of university extension and engagement, and they diverge from models of unidirectional technology transfer. Rather, they emphasize co-construction of knowledge and bi-directional relationships, a feature that resonates with critical Latin American perspectives on the Third Mission (

Alonso et al. 2021).

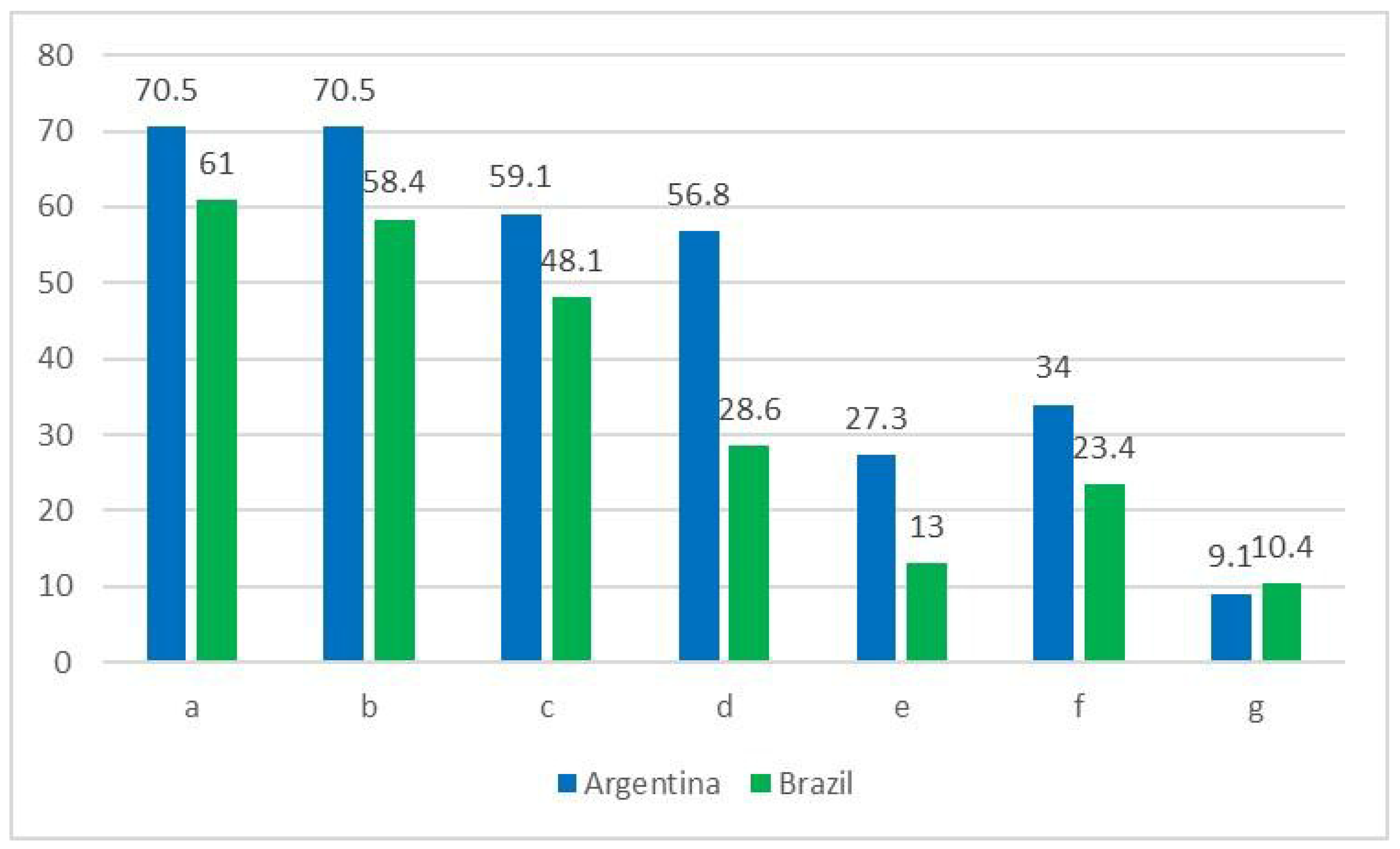

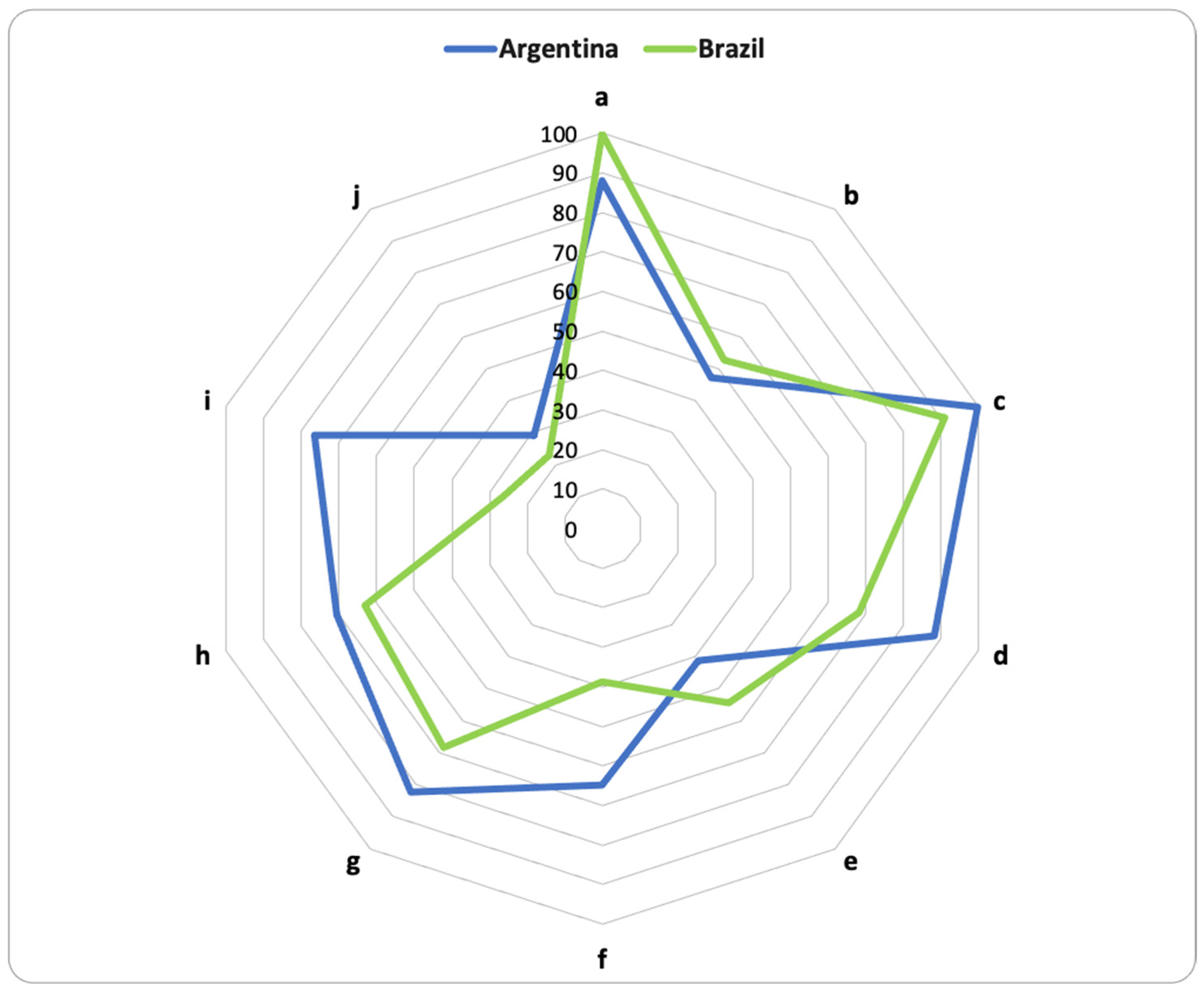

At the same time, in both countries the predominant thematic axes in these university incubators work with the SSE are the environment, health, crafts, art or culture, which denotes the relevant role that they can have in contributing to more comprehensive and sustainable territorial socioeconomic development strategies. Likewise, these university incubators deploy a network of important links with the territorial social innovation ecosystem in SSE in each case, observing that in both countries these links are significant with other incubators and universities, as well as with civil society entities, although to a lesser extent in this last issue. On the other hand, in the case of Argentina the relationship between these university incubators and local administrations or governments is also important, while in Brazil it does not have the same weight.

Finally, the results point to structural asymmetries: Brazil has a broader and more institutionalized social incubation ecosystem, while Argentina shows more fragility. Likewise, the text highlights in both countries the significant construction of academic networks linked to SSE, as well as the important articulation and relational network between these university experiences and the actors in this socioeconomic field. The peculiarity is that in the case of Brazil the main academic network on the subject is specifically in incubation in SSE (ITCP Network), while in Argentina the main networks that were formed in the last decade, particularly RUESS, although they include the different substantive university missions or functions (extension, teaching, research and innovation), do not have as much specificity in what concerns university social incubation.

Brazil has a more significant imprint in terms of incubation, which has a history that precedes the case of Argentina in all the types of incubators that we have considered in this work. In turn, the course of public policies to support and promote them in the case of Brazil, particularly with regard to the university incubators of “popular cooperatives”, has had a specific program for many years and of certain institutional weight, which could have had a greater impact on the creation, evolution and development of these devices, as well as contributing to the formation or strengthening of university incubation teams and spaces linked to the field of these economies.

While the survey provides quantitative evidence of the presence and orientation of university incubators, the broader discussion draws on the literature to interpret these findings. In particular, the data on Brazil illustrate how public programs (e.g., PRONINC, ITCP) have consolidated social incubation, a trend that aligns with previous studies on the institutionalization of SSE support in the region.

This suggests that both countries share a strong commitment to SSE incubation. However, their institutional trajectories and policy frameworks condition the sustainability and impact of these initiatives. At the same time, the results raise new questions about the long-term sustainability of these incubators, their capacity to scale impact, and their role in shaping broader innovation ecosystems in the Global South.

5. Conclusions

The results presented in this article are based exclusively on survey data collected in Argentina and Brazil, and they should be understood as partial evidence within a broader research project. Within these boundaries, three key findings emerge.

First, university social incubators in Argentina and Brazil are more numerous and consolidated than in many European countries. In Brazil, in particular, their growth has been supported by stable public policies and networks (e.g., PRONINC, ITCP), which have allowed incubators to structure their engagement with the SSE more systematically. In Argentina, by contrast, initiatives are widespread but often fragmented and less supported by institutional frameworks. Despite these differences, both contexts demonstrate that university social incubators are strategic tools for connecting universities with local communities and for supporting the creation and consolidation of SSE initiatives.

Second, from a managerial perspective, the results highlight several implications. For incubator managers, the need to design support models tailored to SSE projects, integrating training, mentoring, and territorial networks rather than replicating conventional business incubation practices. For universities, social incubation should be formally recognized as part of the Third Mission, with dedicated resources and stronger involvement of students and faculty. For SSE actors, partnerships with universities can strengthen organizational and managerial capacities, enabling experimentation with innovative governance models and the consolidation of solidarity networks.

Third, from a policy perspective, the Brazilian case demonstrates the importance of stable and institutionalized programs to support social incubation. Policy makers should integrate SSE within broader innovation and development strategies, provide regulatory and financial incentives for university–SSE collaboration, and establish monitoring systems capable of assessing both the social and economic impacts of social incubators.

In conclusion, this article demonstrates—based on survey data from Argentina and Brazil—that university social incubators play a distinctive role in promoting the SSE and in reinforcing the link between universities and territories. While the broader research project also addresses knowledge democratization, this dimension is only briefly acknowledged here. Future studies should further explore how social incubators contribute not only to the consolidation of SSE initiatives, but also to the redefinition of the social role of universities in building more inclusive, sustainable, and democratic societies. Further understanding of university social incubators’ contribution to knowledge democratization will offer deeper insights into their transformative potential.