Unraveling the Heterogeneity of Electoral Abstention: Profiles, Motivations, and Paths to a More Inclusive Democracy in Portugal

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Voter Abstention

1.2. Profiles of Non-Voters

1.3. Focus Groups as a Method for Studying, (De)politicization and Study Electoral Abstention

1.4. Content Analysis (CA) as a Theoretical and Empirical Framework to Study Abstention

1.5. Overview of the Study

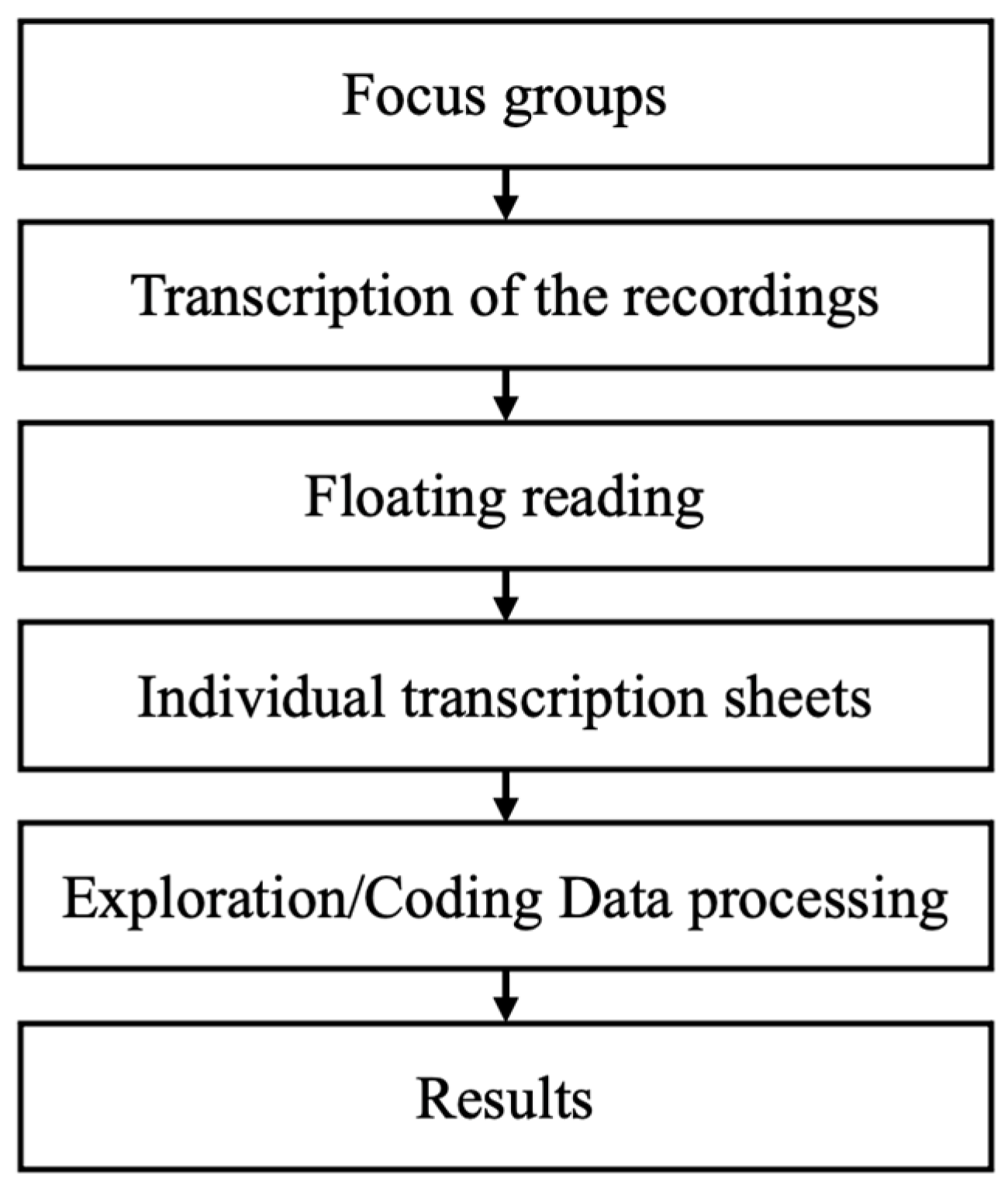

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.1.1. Sample Total

2.1.2. Student Subsample

2.1.3. Non-Student Subsample

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Material

- Q01. What is electoral abstention? How would you define electoral abstention? What meaning do you attribute to it?

- Q02. What does it mean to cast a blank vote? What is a null vote? Are these the same, or can they have different interpretations?

- Q03. Since voting is a right, in your opinion, does it make sense to make voting mandatory?

- Q04. In your opinion, what are the reasons why some people do not vote in elections? // Why didn’t you vote in the last elections (municipal, legislative, presidential, European)?

- Q05. What do you consider to be the profile or characteristics of people who vote // do not vote? What defines them?

- Q06. What motivates your voting behavior (to not abstain)? // What motivates your non-voting behavior (abstention)?

- Q07. What would be an “extreme” situation that would make you decide not to vote? // decide to vote?

- Q08. What is your opinion of people who do not vote? // people who vote?

- Q09. In your opinion, what are the consequences of electoral abstention?

- Q10. What changes would need to occur for more people to participate in elections? What measures could be taken to encourage people to vote? How could we make the voting process more accessible? What role do schools/universities, the media, and civil society organizations play in this context?

3. Results

3.1. Data Curation

3.2. Main Findings

3.2.1. Meaning of Electoral Abstention for Nonvoters and Voters

(NV01, Male, 64 years old, Businessman, Political Party Sympathizer, “Abstention is not a lack of interest, I am informed, but I don’t want to be part of a system that I don’t believe in; NV02, Male, 31 years old, International Relations and European Studies Student, “The meaning of abstention for me is a person who decides not to exercise their right to vote and has the right not to exercise it”).

(NV03, Woman, 33 years old, Master’s degree, “In my case, I never decided to vote. I’ve just never been one for looking at the options and getting ahead of myself. I didn’t feel that I wanted to have an active voice in the country’s decisions; NV14, Female, 20, Languages, Literatures and Cultures Student, Political Party Sympathizer, “Voter abstention is when people don’t go to vote in elections, it’s the choice not to participate in the vote. It can indicate dissatisfaction with politicians or a lack of interest in the election”; VN15, Female, 26 years old, Monitors in a youth association, “Abstention has several meanings, lack of interest, lack of knowledge about what to vote for, lack of availability”).

(V01, Female, 20 years old, Psychology Student, Political Party Sympathizer “Abstention has to do with the fact that we give up a right we have, which is to be represented. Therefore, it puts the proper functioning of democracy at risk; V06, Male, 38 years old, Military member of the GNR—National Republican Guard, Political Party Sympathizer, “Abstaining from elections is giving up a right that we have, which is the vote that was acquired through democracy. By abstaining from voting, we are not choosing to abstain from voting. We are giving up a right that is very important to us. Basically, voting is the basis of democracy, isn’t it? As I see it, that’s the point of view from which people, by abstaining from voting, are losing a great right. They have one of the primary rights that we have as a democratic society”).

(V08, Female, 40 years old, Psychology Student, Political Party Sympathizer, “Many people don’t go to vote, often as an act of showing displeasure or not agreeing with things. And other people simply don’t go because they don’t care”).

(V11, Woman, 47 years old, Mayor, Political Party Sympathizer and Militant, “There’s a lack of interest in party representation in society, and this is a serious risk, and as such, I think there’s a lot of work to be done to get people to vote, at least by raising awareness that we’re losing free democratic systems in the world (…)….] The case of the Algarve is paradigmatic, not in these last elections, which was a different phenomenon, but when we had an abstention rate of 60%, I would say that half the population, the majority, didn’t really choose who they wanted to govern.”)

3.2.2. Nonvoters’ Profiles and Motivations for Choosing Not to Cast a Vote

- The Disbelieving Citizen.

- 2.

- The Disinterested Youth

- 3.

- The Pragmatic Citizen

- 4.

- The Protest Abstainer

3.2.3. Perception of Abstentionists by Voters and Non-Voters

Non-Voters’ Perspective

(NV21, Male, 20 years old, Undifferentiated worker “In a way, people who vote are altruistic. They think about society”; NV17, Female, 42, Unemployed “I think they are informed people, they are people who want to contribute to the country, to the development of the country”).

(NV20, Female, 20 years old, Undifferentiated Worker “I’m completely neutral”).

Voters’ Perspective

(V04, Male, 31, Researcher “People who don’t vote may not be interested in politics. It can also happen that they don’t know how to vote because they’re far away. In fact, this can be due to two things: either because the ways to vote mobile aren’t being well publicized, or because people aren’t interested in actually seeing it”; V05, Female, 21 years old, Psychology student “I think it’s a great lack of interest on the part of those who don’t go to vote”).

(V06, Male, 38 years old, GNR Military—National Republican Guard, Political Party Sympathizer, “In my opinion, I think they are missing a great opportunity to contribute to democracy and to what is expected of citizens. This isn’t just about rights, we also have duties and I think we should fulfill this duty, which is to go and vote”).

3.2.4. Limit Situations That Would Lead Nonvoters to Vote

(NV13, Woman, 41 years old, Integrative Therapist “the vote becoming compulsory”; NV15, Woman, 26 years old, Monitor in a youth association “being forced”; NV16, Woman, 46 years old, Architect “becoming compulsory”).

(NV12, Male, 34, Freelance Artist “To see a noticeable and clear change in the system”; NV13, Female, 41, Integrative Therapist “To believe that there will be a change”; NV10, Male, 42, Computer Engineer “To see that my vote counts”).

(NV01, Male, 64 years old, Businessman, Political Party Sympathizer “In a situation of danger of a totalitarian government”; NV11, Female, 21 years old, Forensic Science Student “In a situation of the extreme right or extreme left governing”).

3.2.5. Perceived Consequences of Electoral Abstention

(NV04, Male, Technical Assistant, Political Party Sympathizer and Militant “The consequence of electoral abstention is the representation of choices that the people don’t always want, but of those who have the power (to vote)”; NV05, Female, 57, Senior Technician, Political Party Sympathizer, “A consequence, because as far as I know, we can have a very high abstention, as there has already been, and still form a government. And I think there are certain numbers from which there should be a red flag and there would be no other mechanisms, in fact, to decide or to understand what it is that people really want or don’t want”).

(V02, Male, 20 years old, Psychology Student, Political Party Sympathizer, “So I think it discredits democracy itself, but also Europe and politics in general in the country”; V03, Female, 21 years old, Psychology Student, Political Party Sympathizer, “The biggest consequence is the lack of representation. In other words, the majority of party positions, which don’t fully cover all the people they actually elect.”

3.2.6. Changes That Could Be Made for Non-Voters to Take Part in the Elections

(NV08, Male, 34 years old, Designer, “Greater transparency, because we grow up hearing stories, since we were little, from our uncle who used to count the votes, and then they close the doors and start dividing up the votes and saying: Go on, take it, this one or more for you, this one for me, that’s it. All these things that we hear from an early age, whether they come from legal sources or not, I think end up accumulating in our heads and creating a system of disbelief in the voting system. That’s why I think that greater transparency, the fact that a technique along the lines of what I was talking about earlier with Bitcoin could be used, would work perfectly and could validate the votes in a unique way and through several computers, in other words, a system that is basically infallible, that can’t be falsified. I think there are several things that can be done at this level.”)

(V03, Female, 21 years old, Psychology student, Political Party and Independent Movement sympathizer, “They extended the days, because normally there are people who can’t, for various reasons or even, if they wanted to, one more day to definitely go and vote. I think it would be beneficial”; V09, Male, 23 years old, Master in Molecular and Translational Neurosciences, Political Party Sympathizer, “The accessibility part, which is also directly linked to the measures we can take to change the openness, such as electronic voting, more accessible transportation for those who can’t get around, less bureaucracy. For example, it’s always important to inform all voters about polling stations, especially young people”; V14, Male, 22 years old, History graduate, Political party sympathizer and activist, “The extension of the voting period. From one day, perhaps, to two or three, I think that if it were extended it would combat abstention. And also electronic voting, I think that if voting was just a click away and there was that facility, I think that many people would end up voting instead of abstaining”).

(NV06, Male, 33 years old, University Professor, “I know it’s complicated, a person only starts voting when they’re 18, but like, in 12th grade maybe explain what happens when people go to vote. I think that schools and universities should intervene (…)”; NV07, Female, “I think that schools and universities could perhaps help with the issue of sharing more information and blocking false information such as fake news and perhaps doing fact checking”).

(V17, Male, 26 years old, Sociology student, Political Party and Independent Movement sympathizer, “Schools need to start teaching citizenship, explaining not only the historical process of achieving democracy, but also what it entails, with more real examples, less theory and more practice. Measures to continue with promotion, through Social Action Associations and those that intervene in society. I think this should also continue to happen because this is part of people’s political socialization, especially young people, who, if I’m not mistaken, have been abstaining more”).

(NV19, Female, 29 years old, Unemployed, “The changes that should be made are at the level of parties and communication. The media is very important in this respect. I think we allow ourselves to be influenced a lot by the media and whether we like it or not, various newspapers, various social communications have partisan tendencies, which end up influencing us.”)

(V15, Male, 40 years old, Football Coach, “Another issue is in the media, we’re seeing the Instagramization and TikTokization of communication, which is just like that, people are watching a video in 10 s and it gets tiresome, 10 s is already too long. So the parties have to modernize there, but there has to be more media, like television and newspapers, etc., there has to be a greater explanation of political programs and greater attention to political debate. We can’t have 15-min debates between parties in 2024. There are things that need to change and improve, even culturally”).

(NV01, Male, 64 years old, Businessman, Political Party Sympathizer, “Essentially, we needed to call on citizens to have more of a say in the country’s decisions. This could be through voting, referendums, they would have to be asked what they really want and not just through a set of ideas that are drawn up by political groups, which, more often than not, are not implemented. Citizens need to feel represented. They need to be the authors of their own and I think that the majority of voters and non-voters don’t feel that way. We, the abstentionists, have been the vast majority, sometimes the absolute majority, of voters in Portugal, and non-voters. But at least we have a large representation in our section of the Portuguese population. And what we’re doing here is very important, because we’re giving them a voice. It’s the first time I’ve been asked why I don’t vote, without being criticized, because we have the right and the duty to do so. So that’s essentially it. There’s a lot to change, but maybe not to make it more complex, but to simplify it”; NV02, Male, 31, International Relations and European Studies student, “There should also be greater awareness among people that they’re not voting for a government, they’re voting for MPs. There should be two elections on that day. The election for who wants to be a government and so there is a person who stands for that, a system that is still in place for prime minister, and this is a set of people for the government, and the person, when it comes to the elections, says again: I want this government, but I prefer this party or this group of citizens to represent me in my region. A group of independent citizens is accepted in the Assembly of the Republic. Let’s say I’m from the Algarve, I want to represent the Algarve in the Assembly of the Republic, I can only run if I’m associated with a political party, even if it’s as an independent, but for that I have to have some sympathy for that political party and I have to be invited by that political party. So there is a barrier to civic participation and democratic participation”).

(N21, Female, 20 years old, Sociology Student, Political Party Militant and Member of Party Youth) “And I think that in relation to votes, a compensation circle, I think that this would also have to be changed, because many votes are lost and good votes that would be important, small parties end up suffering a lot. I think that people also… well, most people sometimes have the idea that their vote won’t count for anything, often because the vote they had, perhaps also for small parties, didn’t count for anything at all. And I think that there should be some measure, some reformulation that would make it possible for people to have a vote that really matters or has meaning”).

(NV20, Male, 23 years old, Sociology Student, Political Party Militant and Party Youth Member, “And then, this also touches on the populism that is the news these days, because we have 12-min debates deciding the future of the country and then there are three-hour programs commenting on what those people said. And you see commentators who often don’t have any information to be commenting on that. So I think it’s… to what extent can we control the media, I’m not going to be the one to say, but it would be a fundamental point to start filtering the information that is given to society in general”).

3.2.7. Meaning of Blank Vote and Null Vote for Non-Voters and Voters

(NV18, Male, 31 years old, Casino Banking Professional, “For me, a blank vote is a protest vote, fulfilling my right to attend the polling station. However, as I don’t identify with any of the candidates, I choose not to participate and not to vote for any of them, while a null vote is a vote that doesn’t meet the requirements of what is asked for on the ballot paper”).

(NV04, Male, Technical Assistant, Political Party Sympathizer and Militant, “Voting blank means that a person does not identify with the parties. Voting null, spoiling the vote with banal jokes, sometimes a bit innocent, or voting in all squares, would be more appropriate as a protest vote”).

(V13, Male, 23 years old, Call-Center Operator, Political Party Militant and Enrolled in Party Youth, “A blank vote is someone who, in fact, has an interest in politics and wants there to be a party that represents them in the future, but who has no party with which they identify. While a null vote can be a lot of things, as I’ve done too, like a cross, a bet, someone who doesn’t know, who can only vote once, for example, there’s also often a lack of knowledge that is just supposed to make a cross. There are people who just draw pictures or two crosses or everything. There may also be the case where the null vote has more to do with votes that perhaps have a few small errors”).

3.2.8. Perception of Mandatory Voting

(NV07, Woman, “It shouldn’t be compulsory. I think that if people want to vote, they should, but if they don’t, they don’t have to either.”; (NV08, Male, 34, Designer, “Everyone has the right to choose what they want or don’t want to do. For me, it was extremely unpleasant to be asked to participate in something that I don’t believe in and with which I think there may be a lack of transparency. There are systems of mechanisms so that voting is not the jungle it is today, in other words, that there are no doubts so that people can clearly see what has happened in the polling stations. This is the case with the cryptocurrency system and Bitcoin, all systems of centralization used for information, which work with a system of validation from different nodes, so that votes can never be repeated, nor can someone vote for me. I think there are much better systems than the current system to ensure that the system itself works well”; NV14, Female, 20 years old, Languages, Literatures and Cultures Student, Political Party Sympathizer, “Since voting is a right, I don’t think it should be compulsory. It’s important that people vote for themselves and understand the importance of it, not just because they have to”).

(V10, Woman, 41 years old, Project Officer, Political Party Sympathizer and Militant, “We should analyze why so many people don’t exercise this right”; (V12, Woman, Journalist, “Well, I’m at a stage where I think I’m leaning towards saying that this is obligatory, because it also hurts a lot to see people abstaining, being rational, being at the time we’re in, of course it’s a right and it shouldn’t be obligatory. However, we need to work hard, using a lot of psychology in particular, so that this right becomes a duty that is very well internalized by all of us”; V11, Woman, 47 years old, Mayor, Political Party Sympathizer and Militant, “The early vote for mobility in these elections was a great demonstration that if there is also a facility for them to exercise this right, because there is a lot of mobility between people, life is not so programmable, there is a lot of movement”; V16, Female, 48 years old, Social Manager and Consultant, Trainer and Mediator, Political Party Sympathizer and Militant, “I think that, for example, for older people, compulsory voting, especially people over 70, compulsory voting shouldn’t exist, but for younger people, I think it should, because otherwise it won’t be exercised. So, in practice, we know that there’s a lot of abstention because, as they’re not obliged, they don’t go”; V15, Male, 40 years old, Football Coach, “In my opinion, it’s about facilitating access to the vote, especially for older people. But not only that. I think the media, especially the state, should have a television program that could emphasize the positive side of voting, create documentaries, create ways of informing people better, because we are very distant, we have people who are already a bit nostalgic for other times and who don’t believe much in politics, and we have young people who are completely, not completely, but very alienated from politics, because it’s uninteresting, because even politicians, most politicians and political parties, can’t and don’t know how to communicate with young people. I’m talking about 18-year-olds, those who are just starting to vote. I think that’s important, to have programs that appeal to people to vote, documentaries and a way of seeing politics in a more positive light. I think that’s the best way to reach people”).

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Policy and Practice

4.2. Avenues for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CIP-UAL | Centre for Research in Psychology—CIP-UAL |

| CUIP | University Research Center in Psychology |

| FPCEUC | Faculdade de Psicologia e de Ciências da Educação-Universidade de Coimbra |

| ENEC | National Strategy for Citizenship Education |

| GNR | Guarda Nacional Republicana |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| Mdn | Median |

| NOTA | None of the Above |

| OSF | Open Science Framework |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

Appendix A

| Non-Voters | Voters | |

|---|---|---|

| Q01. What is electoral abstention? What is your definition of electoral abstention? What meaning do you attach to it? | Electoral abstention refers to the act of not exercising the right to vote, whether for voluntary or involuntary reasons. Some people abstain because they don’t identify with any of the political options presented, thus expressing their dissatisfaction with the system. Others may abstain due to a lack of interest, knowledge or availability at the time of the elections. Abstention can be seen as an indication that something is wrong with the electoral system, leading some to not participate as a form of protest. There are also those who consider a blank or null vote to be a better alternative to abstention. Overall, electoral abstention is a complex phenomenon, with multiple motivations and interpretations. | Voter abstention is the choice not to vote and can be seen as a manifestation of discontent or disinterest. Some people believe it is a form of protest, while others see it as an imperfect choice that allows others to choose for them. Abstention can be a sign of disbelief in the political system, lack of interest or ignorance of electoral programs. It can also be caused by a lack of party representation or discontent with the electoral system. Abstention is seen as a danger to democracy and must be combated. In Portugal, abstention has no value, but some people believe that there should be changes to the political system if abstention exceeds 50%. Abstention is considered a failure to fulfill one’s civic duty and represents a withdrawal from politics. |

| Category | Description |

|---|---|

| Q04. In your opinion, what are the reasons why some people don’t vote in elections? | Some of the main reasons why people don’t vote include: lack of identification with political parties and candidates; concerns about the protection of personal data in the voting process; disbelief in the political system and the ability of politicians to defend citizens’ interests; logistical difficulties such as having to travel or be out of the country on election day; lack of information about the voting process and the options available; lack of interest and knowledge about politics; forgetting the date of the elections or the voter registration process. Many express a sense of distance between politicians and the population, with the perception that politicians only appear during election campaigns. |

| Q05. What do you consider to be the profile/portrayal/image of people who don’t vote? What characterizes them? | People who don’t vote can be characterized by a lack of conviction, hope and belief in the political system. Many are disinterested and disorganized, with a perception that voting makes no difference. Some express discontent with the current situation, conformism or lack of time. Within this group, there is a diversity of profiles, including young people who have no interest in or understanding of politics, as well as people with distrust, indifference, ignorance and dissatisfaction. Some don’t want to exercise their civic responsibility or feel they don’t fit into the system. |

| Q06. What makes you express your non-voting behavior (abstention)? | The behavior of not voting can be motivated by various factors, such as disbelief, revolt and disillusionment with the political system, lack of consistency and confidence in the electoral process, practical difficulties such as transportation costs and bureaucracy, as well as disinterest, forgetfulness and a reluctance to take on the responsibility of voting. Some individuals choose not to vote as a form of self-reflection or to demonstrate their discontent with the current system. |

| Non-Voters | Voters | |

|---|---|---|

| Q08. What do you think of people who don’t vote? | People who don’t vote are viewed differently. Some consider that they are exercising their right and are right not to vote, because they don’t believe in the current system. Others believe that those who vote are more active, informed and democratic, contributing to the country’s development. There are also those who are neutral and respect everyone’s decision. In general, the opinion on non-voters is varied, with some valuing their position and others considering it negative. | People who don’t vote may be disinterested in politics, lack information or be unaware of the consequences of not voting. Some believe that it is irresponsible and selfish not to vote, while others believe that people may be resigned to the current state of affairs or disbelieving in the political system. It is important to remember that being a citizen also involves duties, such as the right to vote, and that it is necessary to seek information in order to make an informed decision. |

| Category | Description |

|---|---|

| Q07. What would be the “in extremis”/limit situation that would lead you to go and vote? | The text presents different perspectives on the limit situation in which a person would vote. Some participants consider that making voting compulsory would be a way for them to go and vote. Others believe that if their vote could make a difference and lead to a noticeable change, with actual changes in the country, this would also mobilize them to vote. There are also concerns about the risk of totalitarian governments, both far-right and far-left, which would drive them to vote. |

| Non-Voters | Voters | |

|---|---|---|

| Q09. In your opinion, what are the consequences of abstaining from voting? | Voter abstention can have several negative consequences for democracy and political representativeness. Some respondents believe that abstention weakens the legitimacy of elected governments, as they do not truly reflect the preferences of the population. In addition, abstention can lead to a lack of motivation for change and the perpetuation of the status quo, with the same groups maintaining power. Some also argue that abstention compromises society, as votes that could make a difference are not counted. On the other hand, other interviewees believe that, despite the high level of abstention, the election results still generally reflect the thinking of Portuguese society. Some suggest that voting blank is a better option than abstaining, as it demonstrates discontent more clearly. In general, abstention is seen as harmful to democracy, as it weakens the representativeness and legitimacy of governments. | Voter abstention has a number of negative consequences, such as a lack of representation and a loss of legitimacy for the democratic system. In addition, abstention can lead to the discrediting of politics and democratic instability. The lack of citizen participation can also result in poor choices and the loss of clear evidence of the popular will. Abstention can also lead to the radicalization of the political system and the weakening of democracy, especially in peripheral areas. It is important that everyone exercises their right to vote in order to guarantee the representativeness and legitimacy of the democratic system. |

| Non-Voters | Voters | |

|---|---|---|

| Q10. What changes would have to take place for more people to participate in elections? What measures could be taken to encourage people to vote? How could we make the voting process more accessible? What role do schools/universities, the media and civil society organizations play in this context? | Some of the main changes suggested to get people to vote more include: Greater transparency and trust in the electoral system, such as through a more secure and traceable electronic voting system. This would help combat disbelief and the stories of fraud that circulate; Make the voting process more accessible and flexible, such as allowing more citizens to vote by post or online, including students and people with reduced mobility. This would facilitate participation; Improve civic and political education from an early age, with subjects in schools and universities that teach students how the political system works, the parties and candidates, and the importance of voting. This would help to form more informed and involved citizens; Greater communication and information efforts by the media, parties and government, in a clear and impartial way, so that people better understand the proposals and options available. This would combat disinformation and the distance between politicians and citizens; Reforming the electoral system, such as having more constituencies and allowing the election of independent MPs, so that Parliament is more representative of the will of the voters. | The changes needed to increase electoral participation include civic education in schools, valuing the blank ballot, accessibility to voting, giving credibility to politics, making political parties accountable, political literacy, raising awareness of politics in schools and in the community, extending the deadline for voting, electronic voting and the use of social media by political parties. It is important to involve young and old in politics and make it more accessible and relevant to people. Schools and universities have an important role to play in raising awareness of politics and civic education. Political parties must work to bring people’s interest into politics and represent them properly. One of the ideas to increase people’s participation in elections is to extend voting days to two or three days, including the weekend, and to modernize electronic voting, reducing bureaucracy. Political parties should also modernize in terms of communication and better publicize their political programs. The media should be less politicized and give equal time to all parties. It is important to have better management of information on how to vote and better participation by the parties for the public. Compulsory voting is not the solution to increasing participation in elections. The implementation of electronic voting and awareness-raising and education in schools are necessary changes to increase electoral participation. It is important that journalists filter information for the general public, while commentators should only give their opinion. Citizenship in schools needs to be reformulated and included in the school curriculum, as does financial literacy. A media overhaul is needed, and all parties should be given equal airtime. Vote compensation also needs to be reformed so that small votes have meaning. Commentators have too much influence on people’s opinions during the election period. |

| Non-Voters | Voters | |

|---|---|---|

| Q02. What does voting blank mean? What does a null vote mean? Do they mean the same thing, can they have different interpretations? | The white vote and the null vote are both considered protest votes, although there are some differences between them. The white vote is seen as a manifestation of discontent with the options available, a way of saying that the person does not identify with any of the parties. A null vote, on the other hand, can be the result of a mistake or an attempt at vandalism, when the person crosses out or fills in the ballot paper in an invalid way. Some participants consider a null vote to be abstention in disguise, while a white vote still demonstrates a belief in the system, even if the person doesn’t identify with any of the alternatives. Despite these differences, both votes are seen as ways of protesting and expressing discontent with the political situation. Some participants believe that, together, white, null and abstention votes can send a strong message of dissatisfaction with the current system. | A blank vote is when the voter doesn’t choose a candidate and leaves the ballot blank. A null vote, on the other hand, is when the voter makes a mistake when casting their ballot, such as putting the cross on more than one candidate or drawing pictures on the ballot paper. Both are ways of expressing dissatisfaction with the options presented, but the null vote can be seen as a more radical protest. Some believe that a blank vote is valid, while others consider it useless. A null vote can be the result of a lack of information or an accidental mistake, but it can also be a form of entertainment on social media. In terms of counting, white votes are counted for whoever wins the election, while null votes are not counted. |

| Non-Voters | Voters | |

|---|---|---|

| Q03. Since voting is a right, in your opinion, does it make sense to make voting compulsory? | The debate about making voting compulsory is complex and involves different perspectives. Some argue that voting is a civic duty and that electoral participation should be compulsory, as there is a large public investment in elections and those who don’t vote can harm the lives of other citizens. Others argue that voting should remain a right, not an obligation, as forcing people to vote can lead to half-hearted votes and a lack of genuine engagement. There is also concern that making voting compulsory could increase white or null votes. Some suggest that instead of making voting compulsory, it is better to invest in civic education so that people understand the importance of voting and exercise this right of their own free will. There is also the question of ensuring adequate conditions so that everyone can vote, regardless of their location. Overall, there is no consensus, with arguments for and against making voting compulsory. | The interviewees have differing opinions on making voting compulsory. Some believe that everyone should exercise their right to vote and that accessibility to voting should be guaranteed, while others argue that forcing people to vote goes against individual freedom. Some suggest that political parties should motivate people to vote, while others advocate the creation of television programs that inform and encourage people to vote. Some respondents suggest that compulsory voting may be appropriate for young people, while others argue that this is not necessary and that raising people’s awareness and education are more important. In general, the interviewees agree that it is important to combat abstention and encourage civic participation. |

References

- Alvarez, R. Michael, D. Roderick Kiewiet, and Lucas Núñez. 2018. A taxonomy of protest voting. Annual Review of Political Science 21: 135–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amnå, Erik, and Joakim Ekman. 2014. Standby citizens: Diverse faces of political passivity. European Political Science Review 6: 261–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, Molly. 2008. Never the Last Word: Revisiting Data. In Doing Narrative Research. Edited by Molly Andrews, Corinne Squire and Maria Tamboukou. London: SAGE Publications, pp. 87–101. [Google Scholar]

- Antunes, Rui. 2008. Identificação Partidária e Comportamento Eleitoral—Fatores Estruturais, Atitudes e Mudanças no Sentido de Voto. Ph.D. thesis, Faculdade de Psicologia e de Ciências da Educação-Universidade de Coimbra-FPCEUC, Coimbra, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Bagozzi, Benjamin E., and Kathleen Marchetti. 2017. Distinguishing occasional abstention from routine indifference in models of vote Choice. Political Science Research and Methods 5: 277–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardin, Laurence. 2011. Análise de Conteúdo. Amadora: Edições 70. [Google Scholar]

- Cancela, João, and Marta Vicente. 2019. Abstenção e Participação Eleitoral em Portugal: Diagnóstico e Hipóteses de Reforma. Cascais: Câmara Municipal de Cascais. Available online: https://research.unl.pt/ws/portalfiles/portal/16817196/Estudo_Portugal_Talks_Absten_o_e_Participa_o_Eleitoral_em_Portugal_2019_1.pdf (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Costa, Bruno. 2010. A abstenção nas eleições para o Parlamento Europeu. Portela: Chiado Editora. [Google Scholar]

- Cramer Walsh, Katherine. 2004. Talking about Politics: Informal Groups and Social Identity in American Life. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dassonneville, Ruth, and Marc Hooghe. 2017. Voter Turnout Decline and Stratification: Quasi-Experimental and Comparative Evidence of a Growing Educational GAP. Politics 37: 184–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Porta, Donatella. 2011. Communication in movement. Information, Communication & Society 14: 800–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deschamps, Jean-Claude, Robert Vicente Joule, and Christel Gumy. 2005. La communication engageante au service de la réduction de l’abstentionnisme électoral: Une application en milieu universitaire. Revue Européenne de Psychologie Appliquée 55: 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sousa, Marcílio, Marcelo Tavares de Melo, and Maria Santiago. 2010. A análise de conteúdo como forma de tratamento dos dados numa pesquisa qualitativa em Educação Física escolar. Movimento 16: 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doppelt, Jack, and Ellen Shearer. 1999. Nonvoters: America’s No-Shows. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Duchesne, Sophie. 2017. Using Focus Groups to Study the Process of (de)Politicization. In A New Era of Focus Group Research. Edited by Rosaline S. Barbour and David L. Morgan. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 365–88. [Google Scholar]

- Duchesne, Sophie, and Florence Haegel. 2004. La Politisation des discussions, au croisement des logiques de spécialisation et de conflictualisation’. Revue Française de Science Politique 54: 877–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchesne, Sophie, and Florence Haegel. 2010. What Political Discussion Means and How Do the French and (French Speaking) Belgians Deal with It. In Political Discussion in Modern Democracies in a Comparative Perspective. Edited by Wolf Michael, Morales, Laula and Ikeda Ken’ichi. London: Routledge, pp. 44–61. [Google Scholar]

- Ehin, Piret, Mihkel Solvak, Jan Willemson, and Priit Vinkel. 2022. Internet voting in Estonia 2005–2019: Evidence from eleven elections. Government Information Quarterly 39: 101718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliasoph, Nina. 1998. Avoiding Politics: How Americans Produce Apathy in Everyday Life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eysenbach, Gunther, and Jeremy Wyatt. 2002. Using the Internet for surveys and health research. Journal of Medical Internet Research 4: 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, André, and Pedro Magalhães. 2002. A abstenção eleitoral em Portugal. Lisboa: ICS. [Google Scholar]

- Gaxie, Daniel. 1978. Le Cens Caché: Inégalites Culturelles et Segrégation Politique. Paris: Le Seuil. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, Mark, and Miki Caul. 2000. Declining voter turnout in advance industrial democracies, 1950 to 1997: The effects of declining group mobilization. Compatative Political Studies 33: 1091–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidi, Camille. 2010. La Société Civile Dans les Cités: Engagement Associatif et Politization Dans des Associations de Quartier. Paris: Economica. [Google Scholar]

- Hastie, Trevor, and Robert Tibshirani. 1990. Generalized Additive Models. Boca Ratton: Chapman & Hall/CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hooghe, Marc, Sofie Marien, and Teun Pauwels. 2011. Where do distrusting voters turn if there is no viable exit or voice option? The impact of political trust on electoral behaviour in the Belgian regional elections of June 2009. Government and Opposition 46: 245–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, Eun-OK, Wonshik Chee, and Hyun-Ju Lim. 2007. Focus group methodology: Rationale and implementation in nursing research. Western Journal of Nursing Research 29: 602–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kamberelis, George, and Greg Dimitriadis. 2014. Focus Group Research: Retrospect and Prospect’ in Patricia Leavy. In The Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research. Oxford: Oxford University Press, Chapter 16. [Google Scholar]

- Kitzinger, Jenny, and Rosaline Barbour. 1999. Introduction: The challenge and promise of focus groups. In Developing Focus Group Research: Politics, Theory, and Practice. London: SAGE Publications, pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, Jan-Erik, and Svante Ersson. 1999. Politics and Society in Western Europe. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, Fernanda, Mayra Alonço, and Olga Ritter. 2021. A análise de conteúdo como metodologia dos periódicos Qualis-CAPES A1 no Ensino de Ciências. Research, Society and Development 10: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, Pedro. 2019. A Participação Política da Juventude em Portugal. Um retrato comparativo e longitudinal, 2002–2019, #01. Gukbenjian Studies—Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian. Available online: https://cdn.gulbenkian.pt/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Relato%CC%81rio-01-final_red.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Martins, Luís. 2023. Como Perder Uma Eleição. Pune: Zigurate. [Google Scholar]

- Microsoft Corporation. 2018. Microsoft Excel. Available online: https://office.microsoft.com/excel (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Minayo, Maria. 1998. O Desafio do Conhecimento: Pesquisa Qualitativa em Saúde, 5th ed. São Paulo: Hucitec-Abrasco. [Google Scholar]

- Moraes, Roque. 1999. Análise de Conteúdo. Revista Educação 22: 7–32. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, David. 1996. Focus Groups as Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Onwuegbuzie, Anthony, Wendy Dickinson, Nancy Leech, and Annmarie Zoran. 2009. A Qualitative Framework for Collecting and Analyzing Data in Focus Group Research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 8: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perea, Eva, and Rui Cabral. 2003. Características individuais, incentivos institucionais e abstenção eleitoral na Europa ocidental. Análise Social 38: 339–60. [Google Scholar]

- Prats, Mariana, Sina Smid, and Monica Ferrin. 2024. Lack of trust in institutions and political engagement: An analysis based on the 2021 OECD Trust Survey. In OECD Working Papers on Public Governance. Paris: OECD Publishing, No. 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. 2022. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 29 August 2024).

- Santos, Fernanda. 2011. Análise de Conteúdo: Visão de Laurence Bardin. Revista Eletrônica de Educação 6: 383–87. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, David, Prem Shamdasani, and Dennis Rook. 2014. Focus Groups: Theory and Practice. London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Tilly, Charles. 2003. Political Identities in Changing Polities. Social Research 70: 605–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Biezen, Ingrid, Peter Mair, and Thomas Poguntke. 2012. Going, going,…gone? The decline of party membership in contemporary Europe. European Journal of Political Research 51: 24–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VERBI Software. 2019. MAXQDA 2024 [Computer Software]. Berlin, Germany: VERBI Software. Available online: https://www.maxqda.com/ (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Zürn, Michael. 2016. Opening up Europe: Next Steps in Politicisation Research. West European Politics 39: 164–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Almeida, N.; Giger, J.-C. Unraveling the Heterogeneity of Electoral Abstention: Profiles, Motivations, and Paths to a More Inclusive Democracy in Portugal. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 601. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14100601

Almeida N, Giger J-C. Unraveling the Heterogeneity of Electoral Abstention: Profiles, Motivations, and Paths to a More Inclusive Democracy in Portugal. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(10):601. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14100601

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlmeida, Nuno, and Jean-Christophe Giger. 2025. "Unraveling the Heterogeneity of Electoral Abstention: Profiles, Motivations, and Paths to a More Inclusive Democracy in Portugal" Social Sciences 14, no. 10: 601. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14100601

APA StyleAlmeida, N., & Giger, J.-C. (2025). Unraveling the Heterogeneity of Electoral Abstention: Profiles, Motivations, and Paths to a More Inclusive Democracy in Portugal. Social Sciences, 14(10), 601. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14100601